ISSUE 29

POETRY

TWO POEMS by Tobi Kassim

TWO POEMS by Karin Gottshall

EXCERPTS FROM “PICTURES OF THE WEATHER” by Timothy Michalik

TRAIL GUIDE TO THE BODY (3RD EDITION) by Lenna Mendoza

TWO POEMS by Monica Cure

TWO POEMS by Kelley Beeson

STILL LIFE WITH DROUGHT, CIGARETTES, AND THE GUADALQUIVIR by Megan J. Arlett

INTAGLIO by Emma Aylor

TWO POEMS by William Fargason

FENNEL by Shelby Handler

ALL THE GOLD I HAVE IS STOLEN GOLD by Liza Hudock

FICTION

THE HUM by Andrea Jurjević

TRANSLATION

[3 UNTITLED POEMS] by Kim Simonsen, trans. Randi Ward

TWO POEMS by Dana Ranga, trans. Christina Hennemann

SPRING SLUMBER by Ma Hua, trans. Winnie Zeng

FIVE FRAGMENTS FROM “THE WOMEN OF ZARUBYAN STREET” by Shushan Avagyan (self-translated)

I AM NOT A NAME by Anna Davtyan (self-translated)

- Published in ISSUE 29

ECOPOETRY FROM JAPAN with Ryoichi Wago and Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FOUR POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

by Judy Halebksy

Ayako Takahashi

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Wago, Ryoichi. Since Fukushima. Trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi. Vagabond Press, 2023. Print.

Purchase the book here.

Screening Time

November 26th, 2011

—exiting the restricted area, a 20 km radius of the power station

screening palms

screening the back of my hands

screening with my hands up

screening with my hands down

screening over my head

screening the back of my head

screening the sole of my left shoe

screening the sole of my right shoe

screening my entire body

screening what is outer space

screening what is a hometown

screening what is life

screening what is radiation

to us

what is most precious

what cannot be measured

You

(no date)

precious

you

what are you

doing now

you are me

I am you

from the obsidian depths of night

it’s you I am thinking about

and for me

from me

you

I won’t give up on

for you

I won’t give up

JANUARY 7th, 2021

I swooned

reeled

reeling.

it was spring, one year after the disaster.

I boarded a helicopter and traveled into the restricted zone,

the 20 km surrounding the nuclear power station,

high above, looking over the land below.

from a perfectly kept beach,

we crossed into the forbidden sky,

as though we were trespassing.

the land left just as it was that day.

huge, concrete wave-breaks strewn on the beach.

houses, cars, and boats hit by the tsunami, scattered everywhere.

mud and stones spread across roads and fields, electric poles keeled over.

dogs chained at front doors and left behind….

time stopped.

no.

time doesn’t exist.

I remembered that.

dizzy. still now.

could be. the aftershocks.

which continue even now, I think.

the other day, I heard a story

from a dairy farmer living within 20 km of the power station.

“the cows were so hungry

there were teeth marks all through the barn and along the fences.

until the end, trying to find something to eat.

they wasted to skin and bones then fell over…”

*

“tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, getting by. an aftershock.

tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, standing here. an aftershock.

a local broadcaster says, now everyone has heard of Fukushima. if we can recover, it’s an opportunity for us, he says. we’re known all over the world. an aftershock.

we clung to hope. tried to be grateful. is there a reward? maybe. but.

our families and our roots are here. famous around the world? I’ll burn the map.

an aftershock.

it’s calm. the night air, radiation. an aftershock.”

(March 22, 2011)

PEBBLES OF POETRY

Part 1: March 16th, 2011, 4:23 am —March 17th, 2011, 12:24 am

Such a huge catastrophe. I was staying at an evacuation center but I’ve now pulled myself together and returned home to work. Thank you for worrying about me and encouraging me, everyone.

March 16th, 2011. 4:23 a.m.

Today, it is six days since the earthquake. My way of thinking has completely changed.

March 16th, 2011. 4:29 a.m.

I finally got to a place where all I could do was cry. My plan now is to write poetry in a wild frenzy.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

Radiation is falling. It is a quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

This catastrophe is so painful, and for what?

March 16th, 2011. 4:31 a.m.

Whatever meaning we can find in all this might come out in the aftermath. If so, what is the meaning of aftermath? Does this mean anything at all?

March 16th, 2011. 4:33 a.m.

What does this catastrophe want to teach us? If there’s nothing to learn from this, what should I believe in?

March 16th, 2011. 4:34 a.m.

Radiation is falling. A quiet quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:35 a.m.

I was taught, “wash your hands before coming in the house.” But there isn’t any water for us to use.

March 16th, 2011. 4:37 a.m.

Relief supplies haven’t arrived in Minamisôma. I’ve heard that the delivery people don’t want to enter the town. Please save Minamisôma.

March 16th, 2011. 4:40 a.m.

For you, where do you call home? I’ll never abandon this place. It’s everything to me.

March 16th, 2011. 4:44 a.m.

I’m worried about my family’s health. They say that this amount of radiation won’t affect us very soon. Is “not very soon” the opposite of “soon”?

March 16th, 2011. 4:53 a.m.

Well, yes, there’s clearly a border between fact and meaning. Some say that they are opposites.

March 16th, 2011. 5:32 a.m.

On a hot summer day, I like to go to a beach on the Minami-sanriku coast. On that exact spot, the day before yesterday, a hundred thousand bodies washed ashore.

March 16th, 2011. 5:34 a.m.

In a quiet moment, when I try to understand the meaning of this catastrophe, when I try to see it clearly there’s nothing, it’s meaningless, something close to darkness, that’s all.

March 16th, 2011. 10:43 p.m.

Just now, while writing, I heard a rumbling underground. Felt the tremors. I held my breath, kneeled down, and scowled at everything swinging. My life or this tragedy. In the radiation, in the rain, no one but me.

March 16th, 2011. 10:46 p.m.

Do you love someone? If it’s possible that everything we have can be lost in an instant, then all we need to do is to find some other way not to be robbed by the world.

March 16th, 2011. 10:52 p.m.

The world has repeated both its birth and death, sustained by some celestial spirit which defies all meaning.

March 16th, 2011. 10:54 p.m.

My favorite high school gym is being used as a morgue for unidentified bodies. The high school nearby, too.

March 16th, 2011. 10:56 p.m.

I asked my mother and father to evacuate but they couldn’t stand to leave their home. “You should go,” they said to me. I choose them.

March 16th, 2011. 11:10 p.m.

My wife and son have already evacuated. My son calls me. As a father, do I have to decide?

March 16th, 2011. 11:11 p.m.

More and more people are evacuating from this town. I know it’s hard to leave. You can do it.

March 16th, 2011. 11:39 p.m.

Having evacuated to a safe place, the young man, twenty-something, is looking at the monitor and crying, “Don’t give up on our dear Minamisôma,” he says. What’s the sense of things in your hometown? Our hometown now, overcome with suffering, faces distorted by tears.

March 16th, 2011. 11:48 p.m.

Again, big tremors. The aftershocks we were expecting finally came. I was wondering if I should shelter under the stairs or just open the front door. Outside, in the rain, radiation is falling.

March 16th, 2011. 11:50 p.m.

The gas is on empty. Out of water, out of food, out of my mind. Alone in this apartment.

March 16th, 2011. 11:53 p.m.

A long rolling tremor. Let’s place our bets, do you win or do I win? This time I lost but next time, I’ll come out fighting.

March 16th, 2011. 11:54 p.m.

Until now, we carried on the daily lives of generation after generation, we searched for happiness, sincerity, I think.

March 16th, 2011. 11:56 p.m.

My elderly neighbor gave me a box full of onions. He grew them himself. Sadly, I’m not much for onions. The box sits in the entryway, I stare at it silently. A few days ago, I was living my ordinary life.

March 16th, 2011. 11:59 p.m.

12 am. Six days since the disaster. A sick joke! Six days since and for five days, I’ve wanted this all to be fixed.

March 17th, 2011. 12:03 a.m.

In the kitchen. Cleaning up scattered, broken dishes. Aching as I put them one by one into the garbage. Me and the kitchen and the world.

March 17th, 2011. 12:05 a.m.

No night no dawn.

March 17th, 2011. 12:24 a.m.

Ryoichi WAGO (1968–) is a poet and high school Japanese literature teacher from Fukushima City, Japan. In 2017, the French translation of his book, Pebbles of Poetry, won the Nunc Magazine award for best foreign-language poetry collection. Since March 2011, his writing has focused on the ecological devastation of the areas affected by the Tôhoku earthquake, tsunami, and the nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power station. Choirs across Japan sing his poem Abandoned Fukushima as a prayer for hope and renewal.

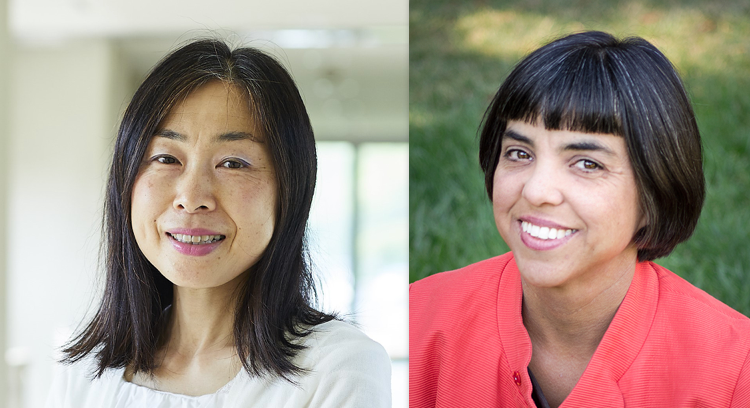

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Alive, the wind

lifts seeds

and carries them away

spider eggs hatch and depart on the wind

over years the wind breaks down plants into soil

we are of the wind and all of our senses

the wind breathing

through us

Within the Trees, A Universe

-Sacred Forest of Kinabatangan, Malaysia

people listen to the trees speak

the trees heard the people

there is light in the woods there was darkness

both life and death

there are voices and so there was silence

within the woods a universe

within the trees a human becomes human

A Mother Speaks

After seeing the noh play, A Killing Stone, Sesshôseki

the play starts in Nasuno province

on the stage there’s a thick purple silk cloth

covering a stone that was dropped

over a field like a cracked rotten egg

a bird flies over the stone and drops

dead to the ground, any living thing, person

or animal that touches that stone dies

a village woman tells the story of this terrifying stone

it starts with her failed attempt to take the emperor’s life

which left her spirit captured within the stone

that now casts spells on the living

when the stone splits open

the village woman appears as a ghost

and the dead return hatching through the stone

pulsing with energy stronger than even the living

the woman’s blaring red rage steadies

and fades to a pale color

the stone again becomes an egg

the defeated become the victors

the lost become found the dead revive

she speaks, the years steal from us

we are robbed of our eggs and escape to the wilderness

we give birth to stone children

hold them in our arms warming the stone

abreast of the thieves who stole our eggs

her ghostly feet glide stamp the ground

a voice within the mask scolds us

echoing from another world

will you be ruled by this bearing always

Rumiko KORA (1932-2021) was a poet, translator, and critic born and raised in Tokyo. Her book The Voice of a Mask won the Contemporary Poetry Prize in 1988. She also wrote essays and novels and co-translated an anthology of poetry from Asia and Africa. She devoted herself to promoting women’s work and was instrumental in establishing the Award for Women Writers. Much of her writing focuses on identifying the struggles and contradictions of a female gender identity.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

MONTHLY with Alexander Duringer

Alexander Duringer is from Buffalo, NY and earned his MFA in Poetry from North Carolina State University. He is a winner of the American Academy of Poets Prize as well as the Bruce & Marjorie Petesch Award. In 2022 he was a finalist for The Sewanee Review’s annual poetry contest. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Plainsongs, Cola Literary Review, The Seventh Wave, The Shore, and Poets.org. He is interviewed for Four Way Review by Matthew Tuckner.

FOUR POEMS by Alexander Duringer

INTERVIEW WITH Alexander Duringer

ISSUE 28

POEMS

OF WINTER AND FIRE by Justin Hunt

DESIRE PATH by Matthew Carter Gellman

THE HISTORIAN’S SHADOW by Malvika Jolly

TWO POEMS by Maria Zoccola

THREE POEMS by deziree a. brown

DOWN IN THE CREVASSE OF LANGUAGE by Henk Rossouw

CHAGALL’S “THE POET WITH THE BIRDS” by Jessica Cuello

I AM AFRAID TO LOVE YOU LIKE MY MOTHER by Jenna Murray

NOUMENON by Cindy King

SHUSHI by Melanie Tafejian

VARIATIONS ON A THEME BY OVID by Daniella Toosie-Watson

THREE POEMS by Sébastien Luc Butler

VOLATILE SUBSTANCES by Olivia Wolford

ANNIVERSARY by Edward Salem

INTERVIEW

TRANSLATION

I WILL REMEMBER by Rahile Kamal trans. Munawwar Abdulla

MOTHER TONGUE by Adil Tuniyaz trans. Munawwar Abdulla

TWO POEMS by Beatriz Pérez Pereda trans. Colleen Noland

RADISH FLOWER by Jang Seoknam, trans. Paulette Guerin and Claire Su-Yeon Park

TWO POEMS by Stefano d’Arrigo trans. Joe Gross

TWO POEMS by Tomas Venclova trans. Rimas Uzgiris

THE PIER by Judita Vaičiūnaitė trans. Rimas Uzgiris

SONG FOR AMERICA by Jacques Viau Renaud trans. Ariel Francisco

ART

- Published in ISSUE 28

BEST OF THE NET 2023 Nominations

POETRY

ROBE AND HELMET BAG by Tommye Blount

COSMOLOGY by Sasha Burshteyn

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT UNSONNET by Dante Di Stefano

DEATH IN SPRING by Mónica Gomery

DETROIT PASTORAL by Brittany Rogers

AFTERMATH by Robert Wood Lynn

FICTION

WET OR DRY by Naomi Silverman

- Published in home

ISSUE 27

ISSUE 27

POETRY

TWO POEMS by Zuleyha Ozturk Lasky

THE POINT OF ARTICULATION by Car Simione

TWO POEMS by Sophia Terazawa

TWO POEMS by Kuhu Joshi

SELF-PORTRAIT AS THE CORNFIELDS by Carolina Hotchandani

TWO POEMS by Daniele Pantano

TWO POEMS by Lucas Jorgensen

FICTION

DOG by Jade Song

NONFICTION

ASUNCION FEVER by Beverly Burch

TRANSLATION

A FLOWER THAT REFUSES TO BE POETRY by Kim Hyesoon, translated by Cindy Juyoung Ok

TWO POEMS by Abdourahman Waberi, translated by Nancy Naomi Carlson

(JANUARY) by Hanna Riisager, translated by Kristina Andersson Bicher

THREE POEMS by Nadja Küchenmeister, translated by Aimee Chor

from YOU by Chantal Neveu, translated by Erín Moure

AROUND THE FIRE by Gloria Susana Esquivel, translated by Joel Streicker

INVITATION TO END by Faris Kuseyri, translated by Patrick Sykes

- Published in ISSUE 27

ISSUE 26

POETRY

TWO POEMS by Sasha Burshteyn

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT UNSONNET by Dante Di Stefano

TWO POEMS by emet ezell

TWO POEMS by Sebastian Merrill

SO MANY by Robin LaMer Rahija

WHY HAVE CHILDREN WHEN THE WORLD IS ENDING by Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach

TWO POEMS by Tana Jean Welch

ELEPHANT by Julien Strong

WHEN BILLIE HOLIDAY SANG by Grace Kwan

FABLE IN WHICH YOU ARE A BARN ANIMAL AND I AM A CARNIVORE by Hannah Marshall

JUNCTURE LOSS by Liane Tyrrel

TWO POEMS by Julia Thacker

FICTION

WET OR DRY by Naomi Silverman

BLOODY AVENUE by Isabella Jetten

TRANSLATION

ANCIENT MOSQUE by Xiao Shui trans. Judith Huang

THREE POEMS by Sandra Moussempès trans. Carrie Chappell and Amanda Murphy

THROUGH THE LAKE, THROUGH THE WATER by Johannes Anyuru trans. Brad Harmon

THREE POEMS by Álvaro Fausto Taruma trans. Grant Schutzman

THE GARDEN IS THIS GARDEN by Hélène Cixous trans. Beverley Bie Brahic

CHEWING BETEL NUT by Mark Dorado trans. Eric Abalajon and Mark Dorado

THREE POEMS by Anne Vegter trans. Astrid Alben

INTERVIEW

with Carrie Chappell and Amanda Murphy

ART

- Published in ISSUE 26

ISSUE 25

POEMS

EN ROUTE by Suphil Lee Park

TWO POEMS by Alexandra Teague

GHAZAL NO. 2 by M. Cynthia Cheung

[MY GRANDFATHER WALKED IN THE SNOW] by Cleo Qian

IN THE END, THE ALEFS CURL by Iqra Khan

THREE POEMS by Mónica Gomery

GEOMETRY by Karen Kevorkian

from PSALMS OF LAMENT FOR DIVINE IMPERATIVES by Jennifer Metsker

TWO POEMS by Jimin Seo

THE PLEASURE IS IN THE WORK by Stella Hayes

WHAT ELSE COULD I HAVE DONE by Mikael de Lara Co

FICTION

MY DINNER THEATRE WITH ANDRÉ by Christopher Hebert

KHOSHBAKHTAM by Kent Kosack

TRANSLATION

from RED MELANCHOLIA by Helena Boberg trans. Johannes Goransson (from SWEDISH)

AND WHAT HAPPENS IF I WANT TO NAME EVERYTHING?, ASKS THE FEMALE DISCIPLE by Mayra Santos-Febres trans. Seth Michelson (from SPANISH)

THREE POEMS by Bronka Nowicka trans. Katarzyna Szuster (from POLISH)

from HOW DARK MY SKIN IS LEFT BY HER SHADOW by Beatriz Miralles de Imperial trans. Layla Benitez-James (from SPANISH)

[UNTITLED] by Vladislav Hristov trans. Katerina Stoykova (from BULGARIAN)

FROM NORTH by Baek Seok trans. Jack Jung (from KOREAN)

WHEN OTHER PEOPLE ARE WRITING POEMS by Oh Kyu-won trans. Jack Jung (from KOREAN)

TWO POEMS by Ashraf Zaghal trans. Ghada Mourad (from ARABIC)

THREE POEMS by Iman Mersal

A grave I’m about to dig

As I return home with a dead bird in my hand, a little grave I’m about to dig waits for us in the backyard.

No blood on the washed feathers, two outspread wings, and a dewdrop (some concentrate of spirit?) on its beak, as if it had flown for many days while actually dead.

Its fall was fated in the Lord’s eyes, heavy and diagonal in front of mine.

I’m the one who left my country back there to go for a walk in this forest, holding a dead bird whose absence the flock never noticed,

returning home for a funeral that might have been solemn and grand were it not for the sneakers on my feet.

A gift from Mommy on your seventh birthday

These are the instructions:

- Spread a tablecloth on level ground.

- Make sure to wear the provided goggles.

- Grab the ax with your right hand.

- Strike the hollow brick very lightly.

- If you strike too hard, you might break the treasure hidden inside.

—I don’t know what the treasure is either, but here’s what’s written on the box: If you’re lucky, a gift from the pharaohs lies inside!

—No, sweetie, no one in Egypt sent this to you, it was made in China.

—Let’s think. Could it be a mummy, with no internal organs? The Great Pyramid’s tomb before the archaeologists discovered it? The head of Cleopatra after she fell in love?

—Those are just guesses . . .

—You won’t know until you break it to pieces.

—Let’s go out to the backyard first. If we do it here, everything will be covered in dust.

A night at the theater

The man on the bus

who cursed our driver for missing his stop

now sings under a lofty balcony,

looking skinny in his fake hair.

His eyes are smaller than I remember.

How did he fall in love with Juliet in less than an hour

while his own wife

(she let everyone know she was his wife)

fights off yawns in the front row

and waits for the play to end?

Juliet was born a very long time ago.

With some help from the stage lights

and her white dress, she looks sad,

and indeed we all know she’s about to die.

Why doesn’t the cameraman take a step

back from the body?

The way he’s doing it

everyone will see

how hard she’s trying not to breathe.

Now members of the two households

remove their stiff costumes,

put away their daggers, and hunt

for trousers and watches.

Some will dash to the bathroom

before going out to take their bows.

If I were Romeo

I’d keep the suicide scene short

so as not to hear

my wife’s snoring.

Translated from the Arabic by Robyn Creswell

- Published in Poetry

INTERVIEW WITH Robyn Creswell

Forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux this fall is the long-awaited collection of poetry by Iman Mersal, translated by Robyn Creswell, titled The Threshold. The author of five books of poems, Mersal is a highly acclaimed Egyptian poet and writer, currently based in Canada, where she teaches Arabic language and literature at the University of Alberta. Her collaboration with Robyn Creswell began when he became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, with an enthusiasm for publishing more Arab poets. In addition to The Paris Review, Creswell’s translations of Mersal’s poems have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Arkansas International, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. To accompany three featured poems by Iman Mersal this September, Four Way Review poetry editor Sara Elkamel spoke with translator Robyn Creswell about The Threshold.

SARA ELKAMEL: Congratulations on your forthcoming collection of Iman Mersal’s poetry in translation, The Threshold (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)! It gathers poems from four of Iman’s collections: A dark alley suitable for dance lessons (1995), Walking as long as possible (1997), Alternative geography (2006), and Until I give up the idea of home (2013). Can you tell us a little bit about the process you went through, together with Iman, to get this collection together? How did you go about selecting the poems?

ROBYN CRESWELL: Iman is a poet of sensibility: she has an immediate, idiosyncratic presence on the page. Her voice—really a congeries of voices—is unforgettable once it gets in your ear. But it’s also a sensibility that develops in large part by looking back on prior performances: reading Iman’s work in chronological order, you have this feeling of astonishing self-sufficiency—her voice expands, matures, and addresses itself to different topics, but the transformations result from self-reflection.

When we chose the poems of The Threshold—and we discussed the table of contents endlessly, because it was fun to arrange and rearrange the poems—I think we wanted to make sure the distinctiveness of Iman’s voice came through, but also its dramatic evolution. So the poems are arranged roughly in the order they were first published, although we also made sure that short and long poems alternate, and the variety of voices is on full display.

SE: You’ve been working with Iman for several years now (I remember reading your gorgeous translation of “The Idea of Houses” in The Nation in 2015). Can you tell us how you first started translating her poetry, and how your evolving collaboration has in turn manifested in the translations?

RC: When I became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, one of my aims was to publish a larger chorus of Arab poets in the magazine. At the time, I think the only poet writing in Arabic who had been published in the Review was Mahmoud Darwish. An Egyptian friend of mine, Waiel Ashry, suggested that I read Iman. At the time, I had what I now recognize as a schoolboyish appreciation of modern Arabic poetry: I mostly read the classics (Darwish, Adonis, Nizar Qabbani, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab), and was suitably awed. Reading Iman was like encountering a contemporary: here was someone who was, I felt, writing the present (to borrow a phrase of Elias Khoury).

I wrote to Iman asking if she might be willing to share some current work with me and among the poems she sent was “A Celebration.” I love that poem—the way it begins with a figure of speech, then literalizes it (“The thread of the story fell to the ground, so I went down on my hands and knees to hunt for it”). Then the juxtaposed scenes of an encounter on a train with an Afghan woman and a patriotic rally in Cairo. The relation between the two episodes, one intimate, the other collective, is never spelled out—it has something to do with the experience of speaking words in a “foreign” language—but the idea of putting them together is what makes the poem characteristic of Iman.

After that first poem we began working on others, until the idea of a book became more or less inescapable. Working with Iman—we’ve worked very closely—has been a pleasure and a privilege. She has a knack for seeing where my English versions aren’t quite right (I’m abashed now to look at some of my first drafts), but she never imposed her own solutions. I’ve learned more from her about Arabic poetry—how it works, its range of tones, its levels of diction—than any other teacher. I’ve been very lucky.

SE: You’ve previously referred to Iman Mersal’s voice as having a “sinuous, rough-edged music” that can be challenging to translate. I also find that irony and wry humor permeate Iman’s poems, which I imagine would be difficult to always carry across into English. Do you remember any particular challenges with translating any of the three poems featured in FWR?

RC: English can do wryness, but Arabic verse has musical possibilities that I don’t think contemporary poetry in English can really capture. Because written Arabic is a literary language—it isn’t spoken except in formal situations—it’s possible to be grandly symphonic or virtuosically lyrical in a way that’s hard to imagine in English. You’d have to be a Tennyson to match the musical effects in Darwish’s late poetry, for example. But of course trying to be Tennysonian would be fatal.

With Iman the difficulty for an English translator is different, and I would say more manageable. In a poem about her father, she wonders whether he might have disliked her “unmusical poems.” I don’t think they’re actually unmusical (I don’t think Iman does either), but their rhythms and cadences and sounds have a lot in common with the spoken language. She writes in fusha, sometimes called “standard” Arabic, but her style shares many features of the vernacular: she doesn’t use ten-dollar words, her syntax is typically straightforward, economy is a virtue. She also uses tonal effects—sarcasm, for example—that we tend to associate with speech.

We talked a lot about “A grave I’m about to dig.” I’m still not sure Iman likes my choice of “diagonal” for the Arabic ma’ilan, to describe the way a bird falling out of the sky might appear to an observer on the ground (but that’s how I think of Iman: she sees things at a slant). The last phrase of the poem, “were it not for the sneakers on my feet” is a typical moment of self-deprecation, a comedy of casualness. There are no feet in the Arabic original, however, which just says “were it not for my sneakers” (or, more literally, “my sports shoes”). I thought adding the phrase “on my feet” was needed, both for musical reasons and because it suggests a pun that isn’t available in Arabic, where verse meters aren’t called feet. For me, Iman’s (musical, metrical) feet really do wear sneakers: they’re quick and agile, casual but spiffy. They’re what we wear today.

SE: Iman’s poems typically take on different forms as well as registers–at times indulging in the lyric, and at times sacrificing it for the sake of a more restrained, almost academic language. She recently told me that she believes poems don’t have “forms” as much as “personalities.” Do you find you have to “get to know” a poem of hers before you approach a translation? If so, what does that process look like?

RC: I think translation is the process—or a process—of getting to know a poem. My first versions tend to be awkward, formal, overly reliant on obvious equivalents (something like the French faux amis). That isn’t so different from the way one talks with a new acquaintance: conventions can be useful. It’s only later, and gradually, that you begin to see what makes the poem—if it’s a good poem—worth spending time with.

SE: Finally, can you tell us a little bit about the choice of title for your forthcoming collection, The Threshold?

RC: “The threshold,” in Arabic al-‘ataba, is an important motif in several of Iman’s poems. It names a site of risk, guilt, transformation. It’s also the title of a long poem that comes at the midpoint of the collection. To my mind, this is Iman’s farewell to the era of her youth. It’s a valedictory poem about Cairo in the nineties, full of Europeanizing elites, posturing poets, and entitled State intellectuals. It’s a poem of the open road that also tells the story of a generation: Iman and her friends wend their way from the Opera House in Zamalek, Cairo’s poshest neighborhood, to the ministry buildings and bars of downtown, through the streets of Old Cairo, and out into the City of the Dead—a burial ground that’s also a point of departure.

–

Robyn Creswell teaches Comparative Literature at Yale University and is a consulting editor for poetry at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is the author of City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut, and a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books.

- 1

- 2