ISSUE 28

POEMS

OF WINTER AND FIRE by Justin Hunt

DESIRE PATH by Matthew Carter Gellman

THE HISTORIAN’S SHADOW by Malvika Jolly

TWO POEMS by Maria Zoccola

THREE POEMS by deziree a. brown

DOWN IN THE CREVASSE OF LANGUAGE by Henk Rossouw

CHAGALL’S “THE POET WITH THE BIRDS” by Jessica Cuello

I AM AFRAID TO LOVE YOU LIKE MY MOTHER by Jenna Murray

NOUMENON by Cindy King

SHUSHI by Melanie Tafejian

VARIATIONS ON A THEME BY OVID by Daniella Toosie-Watson

THREE POEMS by Sébastien Luc Butler

VOLATILE SUBSTANCES by Olivia Wolford

ANNIVERSARY by Edward Salem

INTERVIEW

TRANSLATION

I WILL REMEMBER by Rahile Kamal trans. Munawwar Abdulla

MOTHER TONGUE by Adil Tuniyaz trans. Munawwar Abdulla

TWO POEMS by Beatriz Pérez Pereda trans. Colleen Noland

RADISH FLOWER by Jang Seoknam, trans. Paulette Guerin and Claire Su-Yeon Park

TWO POEMS by Stefano d’Arrigo trans. Joe Gross

TWO POEMS by Tomas Venclova trans. Rimas Uzgiris

THE PIER by Judita Vaičiūnaitė trans. Rimas Uzgiris

SONG FOR AMERICA by Jacques Viau Renaud trans. Ariel Francisco

ART

- Published in All Issues, ISSUE 28

SONG FOR AMERICA by Jacques Viau Renaud trans. Ariel Francisco

America, sitting atop the night’s shoulders

singing in the faces of the hungry

deciphering the language of sadness

measuring the modulation of hatred in our children’s stomachs.

America, they’ve stolen your joy

destroying the muscles in your face

tied your heart to the vigil

where thousands of beings wander

inhabited by death,

a death we drag since men, from beyond,

buried his sword, before your name on this earth.

And the dirt

and the mold

and the mud

of our sun-threshed life.

America, get up America

shake off the dust and rust inside you.

America reborn

reborn America

American men,

American women and children

listen to the tremor rumbling from the Antilles

from that stone peak giving birth

to the voice of a child singing from a tiny island

from the hammering of the scaffold

whose shoulders are built from the blows of cackles

and courage

the pure orb of “American love.”

Listen

a new howl fills the sails of America

dragged by the enemies of man

capitalists,

proxies of the temples and Bibles

in the courts of peace and death

so the truth does not burn Bolivia into thirst,

strangled with a clay cord

the heir of the Inca’s

dead on an eternal bonfire

so the light won’t awaken the sleeping quetzal

atop the ruins of aboriginal silence,

to Chile, long and vibrant,

a spear pierced through the heart of an Araucanian;

to Central America

massacred by dynamited bananas,

to Venezuela

where the capital houses their steepest gallows

and the hosts of love are an impenetrable bastion.

To Brazil with large land and few people

adorning their rags with diamonds

tears on the soldiers lapels

while in Argentina and Paraguay

blood clots hang from the commanders medals

and from chimneys rise the stench of crushed meat.

Oh America!

Now without sail

without compass

bent from hunger

bitter fruit fallen

from a shadeless tree

under whose ruined structure

the American licks the back of sadness.

Oh America!

Piece of the dissected chant,

America, America,

reborn America

burdened men of America

light your bonfires

and march towards the light that guards history.

March

inheritors of blood

Colombian cowboys

with their enormous stomachs

where sunflowers bloom.

Natives of Peru

and Ecuador sleepy with coca

raise the ancient face of purity

and tell your secrets.

And you, Puerto Rico

nailed to the jaws of hatred

small lump of sugar plagued by vermin

slow assassination

crushed between masses of metal and glass.

Oh Puerto Rico

I love you more than any other American homeland

because you permanently inhabit the cry

I love you

I love you

I love you from Santo Domingo

dismembered corpse

shout parted in two

but born of a single throat

from a single anguish,

alone.

Oh America

piece of the dissected chant

with a luminous morning

built by the guerillas of love

who have their widest smile in Cuba.

Oh America

for you so many men fight

for you they die

how much love must be housed

to die for you

for an America not yet born

and won’t be for some time.

Americans of the new gospel

hold in your hands

our heart’s clamor

raise high our cry

tighten the knots that tie us to tenderness

the infant dawn of a smile

tied with your veins

wet with your blood

purified by your cry.

Americans of the new gospel

raise high our cry

so it survives the flood

because it will give birth to generations of happiness

an ample mankind

large as the smile of the proletarian sunrise

forever seedlings of vigor

of spilled love

while life edifies

over the debris of a past life.

Americans of 1963, of this century

evangelizers of the new world

raise your heads

raise them high

to see from afar this land that constitutes our future.

With our remains:

with our hands and bones

with our organs,

with all our being,

with this burdened life,

built to survive,

see it

and do not faint

because we are tomorrow’s fire

the eternal youth

the gesture of those who love

giving everything

taking everything

for this life submerged in your voices.

Jacques Viau Renaud (1941—1965) was born in Haiti and raised in the Dominican Republic following his father’s exile in 1948. During the Dominican Revolution of 1965, he joined the rebel forces in support of ousted president Juan Bosch, fighting against the US backed dictatorship. He was killed in battle at age 23.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

THE PIER by Judita Vaičiūnaitė trans. Rimas Uzgiris

Your torn white shirt lies

drying on the anchor.

In the hush of my cheek

I feel your gypsy hair, while husky

voices echo across the water

and through night’s rusting gear.

Palms timidly touch

the still aching secret scars.

Dawn breaks, and in its light

I can see your heart in your eyes,

waiting for me like treasure received…

O dawn – of boundless brutality and beauty!

Judita Vaičiūnaitė (1937-2001) was one of Lithuania’s leading poets of the second half of the twentieth century. She graduated from Vilnius University in 1959, and spent most of her life in Vilnius. She published over twenty books of poetry, as well as translations of poetry, poetry books for children, and plays. She worked as an editor for several leading literary journals in Lithuania. Her poetry has been translated into English, German, Russian and other languages. Shearsman Books (UK) published a selection of her poems in 2018: Vagabond Sun. Her work has garnered numerous prizes, including the Lithuanian Writer’s Union Prize in 2000, and the national award of the Gediminas Cross in 1997.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

TWO POEMS by Stefano d’Arrigo trans. Joe Gross

WHEN MEEK & THUNDEROUS

When meek & thunderous

spring makes its mooring

& the heart wanes in wax,

honeycomb homilies

flit from fin to wing

of migrant fish & birds

wearing whispers of your name;

we imagine you, because it’s true,

your destination, too, is mystery.

OH IN ITALY A MEMORY

Oh in Italy a memory of the women

who turtledove-strut the windowsills

suddenly thresh their thighs

pulverizing poppies in secret

red petals of their Saracen dresses

fluttering like lustful oriflamme

in defense of the footsteps scrawled

over the island’s wind-worn cobbles.

Stefano D’Arrigo (b. 1919, d. 1992) was born and raised in Alì Terme, Messina, Sicily, but lived and worked in Rome as an art critic much of his life. He is the author of the poetry collection Codice siciliano (Sicilian Code, 1957), the epic Horcynus Orca (1975), the novella Cima delle nobildonne (Noblest of Noblewomen, 1985), and Il licantropo e altre prose inedite (The Lycanthrope and Other Unedited Prose, 2010), and played a minor role in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 directorial debut, Accattone.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

RADISH FLOWER by Jang Seoknam, trans. Paulette Guerin and Claire Su-Yeon Park

Is a path one travels alone also a road?

The radish flower has bloomed

along a hidden path

after others have been planted.

In the swamp, the radish flower has bloomed

without a flag,

without a flagpole,

its heart coming alone,

late spring arriving with only its body.

Woo woo. Like a Molotov Cocktail,

I bloomed late, among the radish flowers.

Roads ahead and behind are blocked by blue barricades of grass and trees,

at the place of the sacred late spring.

I lived a few breathless days

along a road going alone.

Is the road no one walks

a road too?

My yellow pollen

going somewhere in late spring.

Claire Su-Yeon Park, a nursing decision scientist and poetry enthusiast, wove her research journey into three published poems in healthcare journals. Her poetic inspiration is now fueling her groundbreaking interdisciplinary research, illustrating how the poetic imagination inspires creativity in the age of artificial intelligence—a muse for scientific innovation.

Paulette Guerin lives in Arkansas and teaches writing, literature, and film. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Best New Poets, epiphany, Carve Magazine, and others. A suite of 25 poems appears in the anthology Wild Muse: Ozarks Nature Poetry. She is the author of Wading Through Lethe and the chapbook Polishing Silver.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

TWO POEMS by Beatriz Pérez Pereda trans. Colleen Noland

“Untitled”Lucía nursed her anguish for thirty-six years (she didn’t know sadness is an animal that doesn’t understand flattery). There are no pictures of her: she was afraid of the eye in the camera lens, since it was said it could bewitch a soul and make feet clumsy on cliffs. Everything about her is a fable—she could have had six fingers, a third eye, been bald and missing teeth. Or, as some say, she could have been more beautiful than a quiet death—no evidence exists to disprove it. They say she got up and changed the curtains, and her hair was enough to make you love her. They say she was silent as water that watches over dreams of the drowned and her dresses seemed to anchor her to the journey she started as a child. They say she emptied her glass, listened to what her legs demanded. They say the animal praised her, caressed her, in return. I was almost named Lucía. Lucía was my grandmother. “Untitled”A dream: the sea, a port, perhaps the same one where my letters don’t arrive because I don’t know its name. A tiger comes towards me with the remains of a blue deeper than the white-water’s whisper. A tiger carrying a drowned girl’s nostalgia on its fur. A tiger without hunger, waiting to see in my eyes the chains and fire he confuses for home. I approach, and maybe the fear of the salt waves crystallizing or the clouds cacophony make my movements small. I approach, and suddenly I know, by instinct: the tigers are oil paints of water, streaked with fury, mirrors that confess before other tigers. |

Beatriz Pérez Pereda, (Mexico, 1983). A poet and member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte de Mexico, she has received the following awards: the Carmen Alardín National Poetry Prize 2022, Óscar Oliva Poetry Prize 2022, Dolores Castro Poetry Prize 2021, Amado Nervo National Poetry Prize in 2015, among others. She has published several poetry collections: Persona no humana, CONARTE, 2022; Crónicas hacia Plutón, ITAC, 2022; Habitación en sombras, IMAC 2021; Teoría sobre las aves, CECAN 2018; Los sueños del agua, Instituto Municipal de Cultura de Toluca 2013 and La impaciencia de la hoguera, IEC, 2010. She currently teaches poetry workshops and conducts interviews with writers for La Gualdra, the cultural supplement of La Jornada Zacatecas.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

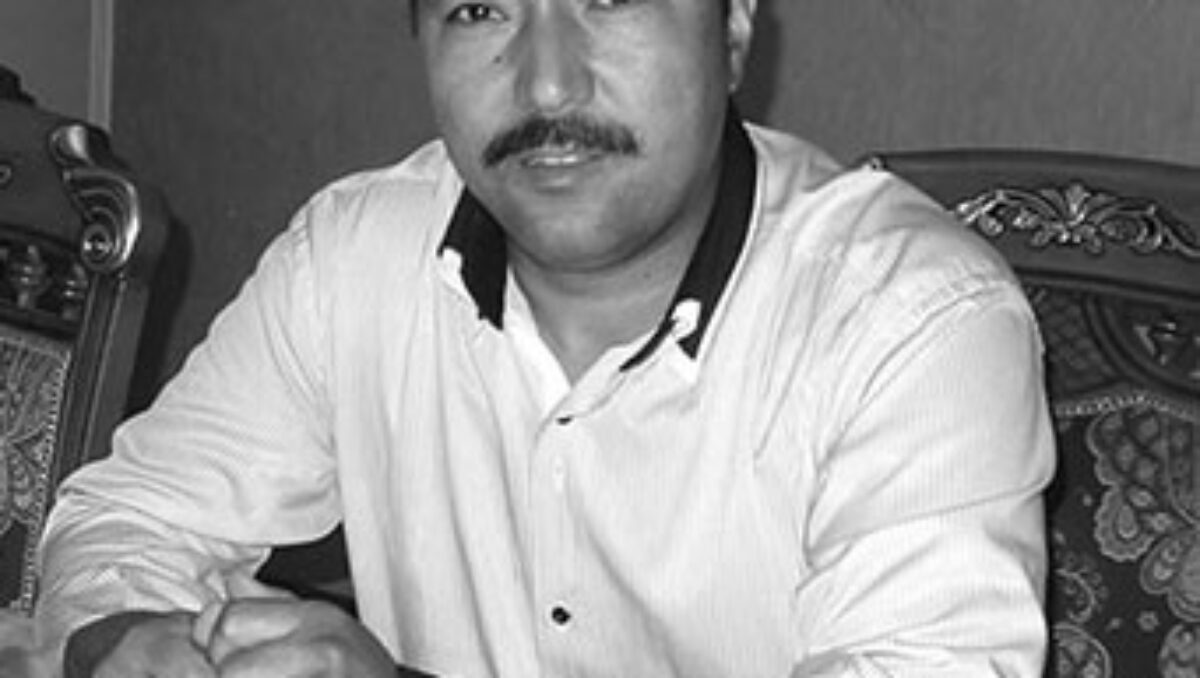

MOTHER TONGUE by Adil Tuniyaz trans. Munawwar Abdulla

We were born like gold

on this sparkling brown land.

It fell, ringing

from the mouth of an Uyghur angel,

its music sunk into our ears.

Oh, mother tongue,

we became wanderers,

and have moved far from your horizons.

Opium poppies

bring the scent of the seas,

thoughts kept moist for a while.

I have left the radio on.

It speaks

in the wind.

Cool orchards

Oil, sandy mountains

A group of people whose colours have drained,

dead still cities and winter pastures.

I drank coffee

and cried.

The ocean waves entered my home.

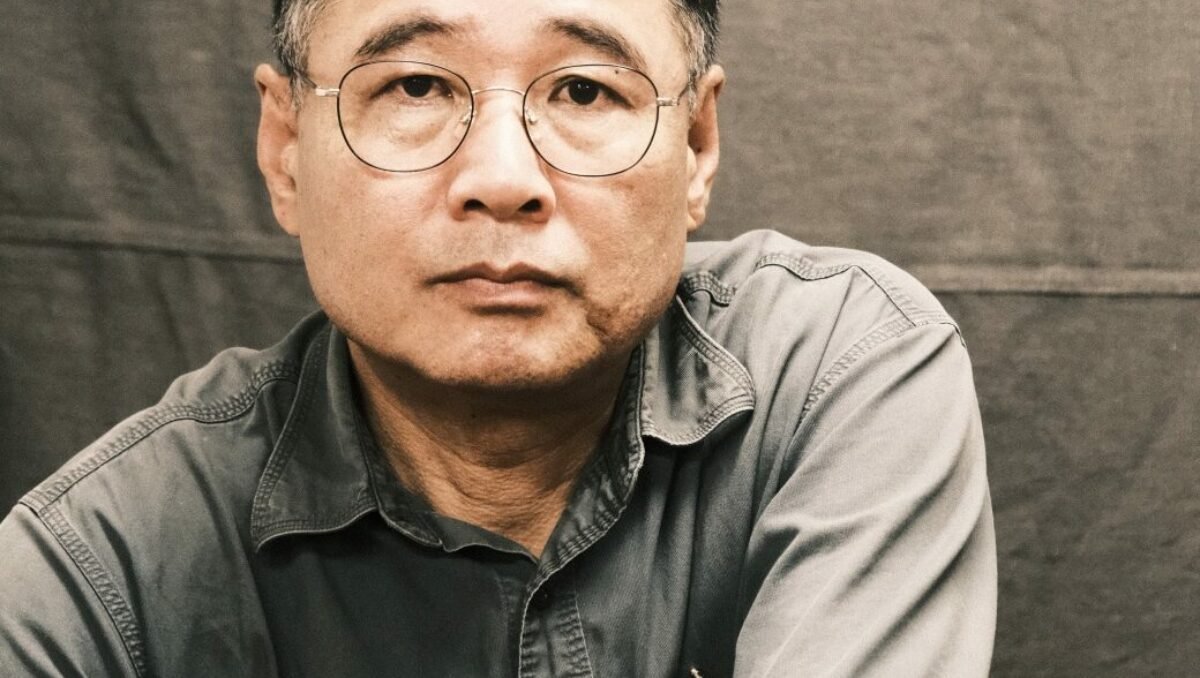

A note on Adil Tuniyaz by Munawwar Abdulla

The current whereabouts of Adil Tuniyaz is unknown. Most likely, he is in a jail in Urumchi, the capital of occupied East Turkistan, in Xinjiang, China.

Adil Tuniyaz, his wife Nezire Muhammad, eldest son Imran, and father-in-law Muhammad Salih Hajim, were all arrested in December 2017 during the Chinese government’s mass incarceration campaign that displaced millions of Uyghurs into re-education camps, prisons, and forced labor factories. The official charges for Tuniyaz and his family’s arrests were “promoting terrorism and religious extremism”. Multiple sources have speculated that the family were detained for their work translating religious texts such as Islamic hadiths into Uyghur. Muhammad Salih Hajim was a prominent religious scholar who was credited with being the first to translate the Quran (with permission from the government). He was confirmed to have died in a re-education camp in January 2018. It is difficult to know the current status of the rest of the incarcerated family.

China has denied the existence of “re-education” camps, then rebranded them as vocational training centers, then defended them as deradicalization training, and now claims that they have closed. Still, the number of prison sentences have skyrocketed, and many of those camps have always been attached to forced labor factories. People from every age group, religion, career, or academic background were targeted with no opportunity to ask for evidence for arrest or appeal for release.

Along with the crackdown on bodies, there has been a crackdown on thought. Knowledge. Language. Many writers, artists, publishers, even literature and anthropology professors, have been given long prison sentences for vague reasons with no trial. Tuniyaz’s cohort of modernist poets included Perhat Tursun, a controversial and secular writer who is now serving 16 years in prison after being arrested in January 2018 for unknown reasons. Another is Tahir Hamut, who managed to escape to the US and write about his harrowing experiences as an artist navigating state control in his book Waiting to Be Arrested at Night (2023).

While we wait to hear of Adil Tuniyaz’s fate, it feels important to share his old poetry. We sink into the softness of his longing for familiar sounds and horizons while in a foreign land. We think of his connection to identity and the way he transposes Islamic mystic elements onto Uyghur cultural motifs. I marvel at the scents and melodies he infuses into his poems. And I note the irony of translating a poem called Mother Tongue, and wonder if I have become unanchored like him, and maybe I should drink coffee, and maybe I should cry.

Adil Tuniyaz (b. 1970) is a well-known poet, journalist, and author of the books Questions for an Apple and Manifesto for Universal Poetry. He is often considered to be among the first generation of modernist Uyghur poets. Publishing his first poem in the journal Xinjiang Youth Daily at just 12 years old, Tuniyaz continued to pursue his passion for literature at Xinjiang University in Urumchi. After graduating in 1993, he became a journalist for Xinjiang Radio while continuing to publish his poems in literary journals, as well as several of his own collections of essays and poetry. In the late 1990s, he left his journalist role to continue his literary studies in Saudi Arabia, returning to Urumchi a decade later. In 2015, he and his wife, Nezire, opened the Light and Pen bookstore. Tuniyaz’s poetry often touches on topics such as Islamic mysticism, Uyghur culture and identity, and many contemporary themes that have made him a popular poet in Uyghur society.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

I WILL REMEMBER by Rahile Kamal trans. Munawwar Abdulla

Today I did not comb my hair

I didn’t even look in the mirror

My kitchen greeted me icily

The walls eyed each other, but didn’t look at me

I wasn’t worth it to those four walls

It’s hilarious that my cat was scared of me

Is my appearance uglier than a cat

Is it so important to dress up

How did I get to this thought

To carry on for a day like I am not living

Doing whatever that comes to mind

To think like those who have gone mad

Firstly, I boiled the coffee in a saucepan

then added a touch of vinegar

I washed my socks in the dishwasher

Found holes in four places

tossed and turned it

and sensed that it was still sound

I tried calling my daughter mum

Can you believe she replied, yes my daughter

I will remember that my mother is also my daughter

I hesitated when it was my husband’s turn

because sometimes I do not recognise him

He has this one look

where my insides end up on my outside

That is the way I am tested

I will try calling him by another name

Wallander, I called, staring at him

Wallander is a Swedish inspector

He didn’t respond, so I repeated, Wallander

Your case is fairly complicated, huh

If we bear it for a day it will unravel itself

A gourd with no water will wear holes in itself from dryness

So he said, looking at himself

Carefully combing my unkept hair

I will remember my husband really is Wallander

The litterfall is my red carpet

The trees sway and flirt

On one foot I wear a boot, on the other a slipper

I wailed loudly in my Uyghur tongue

The Ili roads are winding, winding

On those winding roads, a pair of skylarks sing plaintive

Mournful skylark

I will remember the magnanimity of the trees and litterfall

I came upon a gaunt woman

She froze upon seeing me

then backed away slowly

barely holding back a laugh

Between the two of us one of us is crazy

I know I am faking crazy

If she is also faking crazy

it’s clear then we are both crazy

After the gaunt woman

I arrived upon a four-way intersection

Green, yellow, and red lights

were brushing the road’s pressure points

Ah the highest degree of mania

It is not at all like the imagination

The lights stand around

shining their eyes

There is only colour here

The colour yellow is calm

How mystical is the red

How loving is the green

Some people would say I was calm

when they became toothless snakes and bit me

They would say I was a loving woman

when they hid the sun behind their hems

They would say I was a mystical woman

when I became crazy like this

Again a green light

On yellow we prepare

Red summons

I raised my right leg

I raised it and

I saw a woman stretched out on the ground

Her white hair uncombed

On her right foot a boot, on her left a slipper

Mournful and restless

Oh, this crazy, whining woman

said the gaunt woman

whispering

Oh, this lunatic woman

said the cat

muttering

The woman lying on the floor looked like me

but was not me

The green light was still on

I will remember the countenance of the colour green

I recalled all my memories

My vinegar flavoured coffee

My holey socks

My daughter mother

Wallander

My litterfall

My madness

These are all my green lights

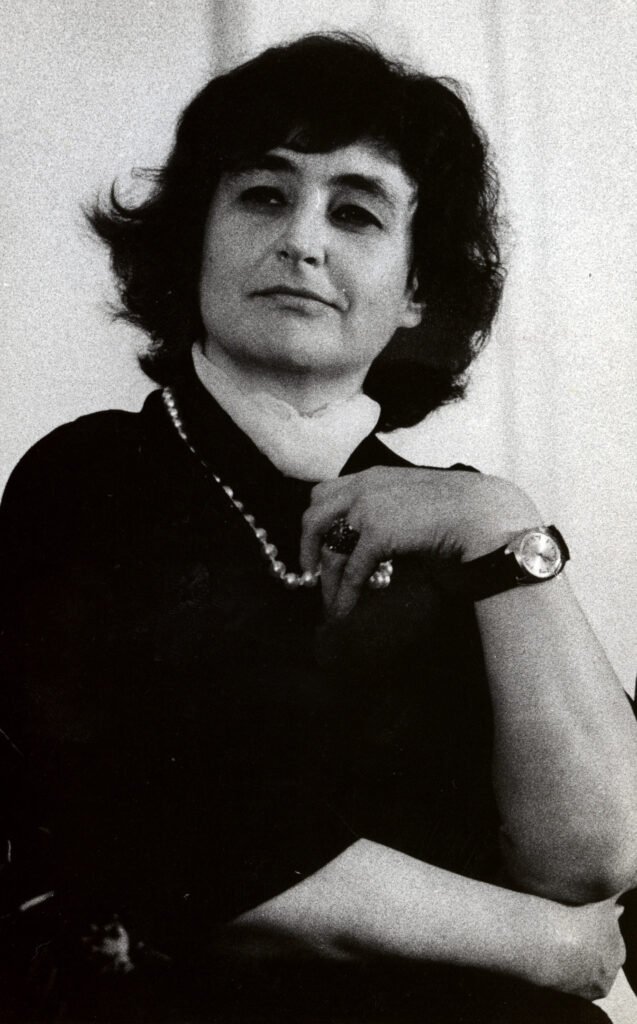

Rahile Kamal is a poet born in Ghulja, East Turkistan, where she worked as an editor, reporter, and editor-in-chief at the Ili Evening Newspaper from 1993 until 2004. She was a prolific writer, publishing numerous poems and other literary works in various newspapers and magazines, many of which received prestigious awards. However, after migrating to Sweden in 2004, it was only after 2016 that Rahile rekindled her passion for writing and began publishing again in journals such as Izdinish and Ittipaq. Her poems have been translated to Turkish, Japanese, Chinese, and English. In May 2022, she published her poetry collection titled Kamal is Gone in Istanbul, and she has upcoming work in the anthology Uyghur Poems, which will be published by Penguin Random House in November 2023.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

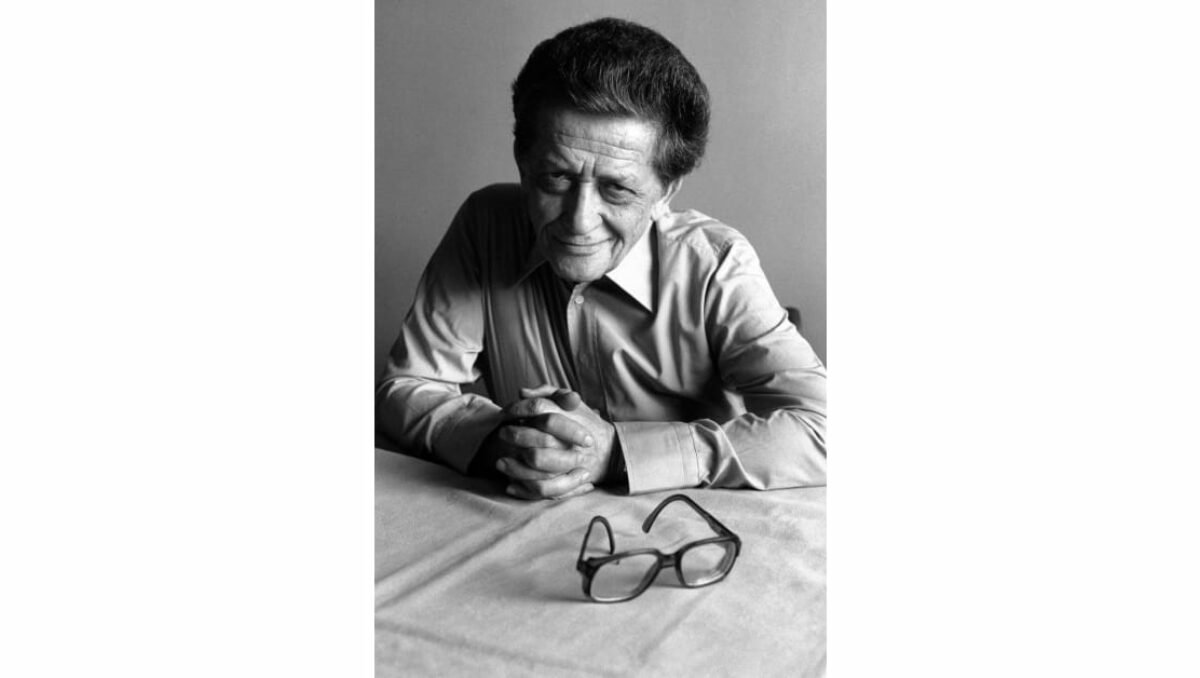

INTERVIEW WITH Jared Harél by Urvashi Bahuguna

Jared Harel’s poems are quiet records of the layers inside the ordinary days of our lives, exposing the restless forces and memories that power and threaten our most mundane actions. In “Behind The Painted Railguard,” the poet is standing in an amusement park with his mother, watching his young son on a ride. He uses that particular scene to reflect on the past, expectations, family lore, acceptance, difficult silences – the breadth of what he covers is a testament to Harel’s relationship to craft. His crisp lines and clear, effective imagery accompany us throughout his second collection, Let Our Bodies Change The Subject (University of Nebraska Press, September 2023), as we move through poems that are anchored in themes of parenting, marriage, and family, and that contend with the inherent pain of being alive. Harel has won multiple awards for his writing including the Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize, the William Matthews Poetry Prize, Diode Editions Book Award, and 2022 Raz/Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry. He lives with his family in Westchester, NY.

FWR: The collection’s opening and closing poems really appear to speak to one another. I love that we begin with a child trying to puzzle out death and end with a child who has learnt that the world is less magical than they first believed. Were you conscious of that implied journey as you ordered the poems? What is your process when it comes to ordering a manuscript?

JH: First off, thank you for taking the time to dig into my new collection! I knew I wanted to open the book with “Sad Rollercoaster” as an introduction to themes of parenthood, mortality, NYC and more. My decision to end on “Dolls Can’t Talk” took longer to figure out.

When giving shape to a poetry manuscript, my process is to print the poems and spread them out on my kitchen floor. Certain poems I know I want close together, while others I want to keep apart. Then I pay particular attention to the beginnings and endings of poems. For instance, does the closing line of ‘Poem A’ link well or create an interesting friction with the opening line of ‘Poem B’? Kinda like train cars. Then I trust this momentum to carry the reader forth.

On a larger scale, beginning the collection with the line, “My daughter is in the kitchen, working out death” then ending, “How long have you suspected/we might be alone?” felt like the right arc and tension for this book.

FWR: As I read and re-read the book, I had this overwhelming sense of witnessing deep love. As someone who writes about central relationships in her life as well, I would love to hear about how you navigate writing about the relationships in this book. How does the personal affect your craft or the lens you choose to turn upon these subjects?

JH: Honestly, I try not to worry about this too much when making poems. My goal is to write the best poem I can—something that feels true and conveys both a passion for language and the experience behind the words. I’ve often been asked about the decision to include my children in my poems. The truth is, I don’t know how to keep them out. Sometimes I’ll be writing and my son will literally leap onto my lap. If I’m interested in writing poems from a genuine place, these people who give shape and meaning to my life (my kids, parents, siblings, friends, spouse) will continue, I imagine, to appear organically in my work.

That being said, I do think there’s a difference between writing poems and the public decision to publish them. There’s one poem from my first collection, Go Because I Love You, which I kinda regret putting in the book. It’s one about my parents, and while I think it’s a strong poem, I’m no longer sure it was my place to publish it.

FWR: “You Want It Darker (2016)” also appeared, if I am not mistaken, in a previous collection. The choice to include it again intrigues me. What brought that about? (I apologize if I am mistaken.)

JH: Good catch! You are not mistaken. I wrote “You Want It Darker” in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Those were dark days made darker by the fact that Leonard Cohen passed away that very same week. In my poem, I aimed to articulate a collective, community-wide grief I felt around Queens, NY at the time.

Years later, I drafted a new poem in the hours leading up to the 2021 Presidential Inauguration, and titled it simply “January 20, 2021.” That poem felt like a long-awaited exhale and a bookend to “You Want It Darker.” For that reason, it made sense for me to include both poems, one after the other, in this new collection.

To my delight, “January 20, 2021” was the Academy of American Poets ‘Poem-a-Day’ on January 20, 2022, exactly one year after it was written. In any case, fingers crossed there’s no third poem to this series!

FWR: “Our Wedding” is one of my favorite poems from this collection. I am so curious about the genesis of it. Is the speaker many years removed from the event? Why did the poem come to the poet now? Or is it something they have been working on for a long time?

JH: By the time I wrote “Our Wedding,” my wife and I had been married for 11 years, so it certainly wasn’t written on the heels of the event. Actually, we’d just attended my cousin’s wedding, which got us thinking about our own ceremony and party, how young we’d been, and how today – as “proper adults” – we’d do things differently. That opening couplet, “It wasn’t what we wanted,/but we wanted each other” hit me the next morning, and the poem developed from there.

FWR: You’re a drummer. What does that bring to your life?

JH: I’m drawn to the social and collaborative aspects of being a drummer in a rock band. My bandmates and I write songs and play music together, which is totally different from the solitary act of making poems.

Thinking about similarities though, there’s definitely the element of rhythm to both. Whether writing or drumming, I’m driven by cadence and beat. When revising, I’ll read and re-read my poem-draft out loud, tapping my foot to underscore certain rhythms. I often find myself tapping my foot while in the audience at poetry readings as well.

FWR: Whose work (they don’t necessarily have to be writers) are you invigorated by at the moment?

JH: Reading and writing are fairly simultaneous activities for me. Most of the time I spend “writing”, I’m actually reading from a stack of books on my desk. Sometimes my poems begin in dialogue with what I’m reading, or something I read may trigger a memory. Some poetry collections on my writing desk today include Refusing Heaven by Jack Gilbert, Judas Goat by Gabrielle Bates, Hard Damage by Aria Aber, Previously Owned by Nathan McClain, If Some God Shakes Your House by Jennifer Franklin, Might Kindred by Mónica Gomery and Mouth Sugar & Smoke by Eric Tran. The works of Elizabeth Bishop, Wislawa Szymborska, Lucille Clifton, Larry Levis and Terrance Hayes seem to be permanent fixtures in these stacks as well.

Musically, I’m all over the place. I also find that good stand-up comedy really keys in on important poetic aspects such as rhythm, specificity, word-choice and subverted expectations. What makes poems and jokes work are often one and the same.

FWR: I would love to hear more about how standup comedy influences or challenges how you approach your writing.

JH: To be clear, I’ve never tried standup, and am by no means an expert on the subject! I simply get inspired when I see it done well, much like reading a great book makes me want to write. You might’ve heard the phrase, “It’s funny because it’s true.” Both comedians and poets seek, as Dickinson put it, a kind of slanted truth—a fresh way of getting at shared experiences through the particulars and peculiarities that make life interesting.

FWR: On a related note, are there poets who use humor in their work whose work you enjoy?

JH: Yeah, Natalie Shapero writes some of the funniest – and sharpest, and most heartbreaking – poems around. Shapero has one poem from her latest collection, Popular Longing, that begins, “So sorry about the war—we just kind of/wanted to learn how to swear/in another language” and another poem with the lines, “Last week I read a novel about a man/so awful that when he died I wept/because it was fiction.” Much like a great comic, Shapero utilizes line-breaks and enjambment to dictate pace, build set-up, then deliver the punch-line. Carrie Fountain is another poet who writes these brilliant, humorous meditations on parenting, love, God, etc. They’re funny because they feel so accurate and lived in, and because humor isn’t so much the “goal” as it is a natural byproduct of writing about this strange, sad, wonderful world.

FWR: “Birthday” (which appeared in Four Way Review!) is such an incredible combination of restraint and impact. I am really curious about the editing process for this particular poem. Was the first draft pretty similar to the final version of the poem? Would you talk us through it a little bit?

JH: I appreciate that. Restraint is the right word here. A friend of mine, the excellent poet, Rosebud Ben-Oni, instructs her students to “be careful not to edit before you write.” Great advice, but that’s exactly what I wound up doing with this one, taking it line by line and slowly working my way down the page. So often, writing is an act of discovery, but with this particular poem – based on a conversation I’d just had with my daughter – I knew my target. It was just a question of hitting the mark and paring back language to make sure the poem didn’t spiral into sentimentality. By the time I’d reached the last line, the vast majority of my editing was done. My first version and final version of this poem are nearly identical.

FWR: Is there a poem in this collection that you were surprised to find yourself writing?

JH: Despite what I just said about “Birthday”, some of my favorite moments as a writer are when I surprise myself, or say something I didn’t know I knew. One poem from Let Our Bodies Change the Subject that took me completely by surprise was “Survival Mode.” That one is nearly a word-for-word transcription of one of the stranger conversations I’ve ever been a part of. I found myself more or less writing it in real time, in my head and on a napkin. Then I raced upstairs and typed it out. It was one of those rare occasions where a poem appeared before it even registered that I was writing one at all.

FWR: A poem I return to over and over is “The Other Side of Desire.” I could see an argument for placing a poem like this — one that establishes conflict and ambivalence — in the middle of a collection and I am fascinated by the fact that it comes so close to the end. Can you talk about that choice a little bit?

JH: That’s an interesting question. I guess I don’t think of “The Other Side of Desire” as a poem about ambivalence, but about commitment and love in the face of imperfection and the dailyness of existence. “The Other Side of Desire” directly follows “Spring Crush” and “Slow Dance” in my collection, both of which are poems about young, early and first loves. “Slow Dance” concludes: “Whatever I hold close begins then.” Of course, what sustains a strong relationship is more than just infatuation and attraction. It also takes work, mutual respect, and these constant, almost invisible decisions to be present in your life and the life of your partner. Placing this poem near the end of the collection, for me, was less about establishing conflict than owning up to the responsibility of our decisions, maybe especially our best decisions.

ANNIVERSARY by Edward Salem

Kneeling to carve back the grass encroaching

like cuticles on a fingernail, I noticed how close

her flat headstone was to the others around hers.

Watering the flowers at his wife’s grave,

an old man told me they’re placed above

the abdomens, not the heads, as you’d expect.

I think he meant to explain they were less crowded

underground than it appeared, but I didn’t follow.

I pictured a pair of rotten feet standing on my mother’s

head, her green feet standing on another’s head,

and so on in a horizontal grid, gaudy totem poles.

I wasn’t sure what part of her body I stood over,

but I stepped aside as if she could feel my weight,

like when I was a child and she’d lie on the carpet

and tell me to walk all over her back. I’d laugh

at the funny feeling underfoot, the squishy,

bony, fleshy ground I massaged by walking,

losing my wobbly balance turning around

after each short lap from shoulders to butt. Yet

standing off to the side of her grave felt wrong.

Every year, every visit, like the bashing of a gong.

- Published in ISSUE 28

VOLATILE SUBSTANCES by Olivia Wolford

These toys:

Stacked so short of the sky.

Horizon of thorns. Every cresting wave

The taunting laugh

Of the long game.

There are things only

Human hands are built for:

To screw, to unscrew.

Fingers in the saltwater

Scramble

Your second language,

Mistaking

Fish

For

Sin.

- Published in ISSUE 28

- 1

- 2