ISSUE 25

POEMS

EN ROUTE by Suphil Lee Park

TWO POEMS by Alexandra Teague

GHAZAL NO. 2 by M. Cynthia Cheung

[MY GRANDFATHER WALKED IN THE SNOW] by Cleo Qian

IN THE END, THE ALEFS CURL by Iqra Khan

THREE POEMS by Mónica Gomery

GEOMETRY by Karen Kevorkian

from PSALMS OF LAMENT FOR DIVINE IMPERATIVES by Jennifer Metsker

TWO POEMS by Jimin Seo

THE PLEASURE IS IN THE WORK by Stella Hayes

WHAT ELSE COULD I HAVE DONE by Mikael de Lara Co

FICTION

MY DINNER THEATRE WITH ANDRÉ by Christopher Hebert

KHOSHBAKHTAM by Kent Kosack

TRANSLATION

from RED MELANCHOLIA by Helena Boberg trans. Johannes Goransson (from SWEDISH)

AND WHAT HAPPENS IF I WANT TO NAME EVERYTHING?, ASKS THE FEMALE DISCIPLE by Mayra Santos-Febres trans. Seth Michelson (from SPANISH)

THREE POEMS by Bronka Nowicka trans. Katarzyna Szuster (from POLISH)

from HOW DARK MY SKIN IS LEFT BY HER SHADOW by Beatriz Miralles de Imperial trans. Layla Benitez-James (from SPANISH)

[UNTITLED] by Vladislav Hristov trans. Katerina Stoykova (from BULGARIAN)

FROM NORTH by Baek Seok trans. Jack Jung (from KOREAN)

WHEN OTHER PEOPLE ARE WRITING POEMS by Oh Kyu-won trans. Jack Jung (from KOREAN)

TWO POEMS by Ashraf Zaghal trans. Ghada Mourad (from ARABIC)

- Published in All Issues, ISSUE 25, Issues 2

THREE POEMS by Iman Mersal

A grave I’m about to dig

As I return home with a dead bird in my hand, a little grave I’m about to dig waits for us in the backyard.

No blood on the washed feathers, two outspread wings, and a dewdrop (some concentrate of spirit?) on its beak, as if it had flown for many days while actually dead.

Its fall was fated in the Lord’s eyes, heavy and diagonal in front of mine.

I’m the one who left my country back there to go for a walk in this forest, holding a dead bird whose absence the flock never noticed,

returning home for a funeral that might have been solemn and grand were it not for the sneakers on my feet.

A gift from Mommy on your seventh birthday

These are the instructions:

- Spread a tablecloth on level ground.

- Make sure to wear the provided goggles.

- Grab the ax with your right hand.

- Strike the hollow brick very lightly.

- If you strike too hard, you might break the treasure hidden inside.

—I don’t know what the treasure is either, but here’s what’s written on the box: If you’re lucky, a gift from the pharaohs lies inside!

—No, sweetie, no one in Egypt sent this to you, it was made in China.

—Let’s think. Could it be a mummy, with no internal organs? The Great Pyramid’s tomb before the archaeologists discovered it? The head of Cleopatra after she fell in love?

—Those are just guesses . . .

—You won’t know until you break it to pieces.

—Let’s go out to the backyard first. If we do it here, everything will be covered in dust.

A night at the theater

The man on the bus

who cursed our driver for missing his stop

now sings under a lofty balcony,

looking skinny in his fake hair.

His eyes are smaller than I remember.

How did he fall in love with Juliet in less than an hour

while his own wife

(she let everyone know she was his wife)

fights off yawns in the front row

and waits for the play to end?

Juliet was born a very long time ago.

With some help from the stage lights

and her white dress, she looks sad,

and indeed we all know she’s about to die.

Why doesn’t the cameraman take a step

back from the body?

The way he’s doing it

everyone will see

how hard she’s trying not to breathe.

Now members of the two households

remove their stiff costumes,

put away their daggers, and hunt

for trousers and watches.

Some will dash to the bathroom

before going out to take their bows.

If I were Romeo

I’d keep the suicide scene short

so as not to hear

my wife’s snoring.

Translated from the Arabic by Robyn Creswell

- Published in Poetry

INTERVIEW WITH Robyn Creswell

Forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux this fall is the long-awaited collection of poetry by Iman Mersal, translated by Robyn Creswell, titled The Threshold. The author of five books of poems, Mersal is a highly acclaimed Egyptian poet and writer, currently based in Canada, where she teaches Arabic language and literature at the University of Alberta. Her collaboration with Robyn Creswell began when he became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, with an enthusiasm for publishing more Arab poets. In addition to The Paris Review, Creswell’s translations of Mersal’s poems have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Arkansas International, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. To accompany three featured poems by Iman Mersal this September, Four Way Review poetry editor Sara Elkamel spoke with translator Robyn Creswell about The Threshold.

SARA ELKAMEL: Congratulations on your forthcoming collection of Iman Mersal’s poetry in translation, The Threshold (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)! It gathers poems from four of Iman’s collections: A dark alley suitable for dance lessons (1995), Walking as long as possible (1997), Alternative geography (2006), and Until I give up the idea of home (2013). Can you tell us a little bit about the process you went through, together with Iman, to get this collection together? How did you go about selecting the poems?

ROBYN CRESWELL: Iman is a poet of sensibility: she has an immediate, idiosyncratic presence on the page. Her voice—really a congeries of voices—is unforgettable once it gets in your ear. But it’s also a sensibility that develops in large part by looking back on prior performances: reading Iman’s work in chronological order, you have this feeling of astonishing self-sufficiency—her voice expands, matures, and addresses itself to different topics, but the transformations result from self-reflection.

When we chose the poems of The Threshold—and we discussed the table of contents endlessly, because it was fun to arrange and rearrange the poems—I think we wanted to make sure the distinctiveness of Iman’s voice came through, but also its dramatic evolution. So the poems are arranged roughly in the order they were first published, although we also made sure that short and long poems alternate, and the variety of voices is on full display.

SE: You’ve been working with Iman for several years now (I remember reading your gorgeous translation of “The Idea of Houses” in The Nation in 2015). Can you tell us how you first started translating her poetry, and how your evolving collaboration has in turn manifested in the translations?

RC: When I became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, one of my aims was to publish a larger chorus of Arab poets in the magazine. At the time, I think the only poet writing in Arabic who had been published in the Review was Mahmoud Darwish. An Egyptian friend of mine, Waiel Ashry, suggested that I read Iman. At the time, I had what I now recognize as a schoolboyish appreciation of modern Arabic poetry: I mostly read the classics (Darwish, Adonis, Nizar Qabbani, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab), and was suitably awed. Reading Iman was like encountering a contemporary: here was someone who was, I felt, writing the present (to borrow a phrase of Elias Khoury).

I wrote to Iman asking if she might be willing to share some current work with me and among the poems she sent was “A Celebration.” I love that poem—the way it begins with a figure of speech, then literalizes it (“The thread of the story fell to the ground, so I went down on my hands and knees to hunt for it”). Then the juxtaposed scenes of an encounter on a train with an Afghan woman and a patriotic rally in Cairo. The relation between the two episodes, one intimate, the other collective, is never spelled out—it has something to do with the experience of speaking words in a “foreign” language—but the idea of putting them together is what makes the poem characteristic of Iman.

After that first poem we began working on others, until the idea of a book became more or less inescapable. Working with Iman—we’ve worked very closely—has been a pleasure and a privilege. She has a knack for seeing where my English versions aren’t quite right (I’m abashed now to look at some of my first drafts), but she never imposed her own solutions. I’ve learned more from her about Arabic poetry—how it works, its range of tones, its levels of diction—than any other teacher. I’ve been very lucky.

SE: You’ve previously referred to Iman Mersal’s voice as having a “sinuous, rough-edged music” that can be challenging to translate. I also find that irony and wry humor permeate Iman’s poems, which I imagine would be difficult to always carry across into English. Do you remember any particular challenges with translating any of the three poems featured in FWR?

RC: English can do wryness, but Arabic verse has musical possibilities that I don’t think contemporary poetry in English can really capture. Because written Arabic is a literary language—it isn’t spoken except in formal situations—it’s possible to be grandly symphonic or virtuosically lyrical in a way that’s hard to imagine in English. You’d have to be a Tennyson to match the musical effects in Darwish’s late poetry, for example. But of course trying to be Tennysonian would be fatal.

With Iman the difficulty for an English translator is different, and I would say more manageable. In a poem about her father, she wonders whether he might have disliked her “unmusical poems.” I don’t think they’re actually unmusical (I don’t think Iman does either), but their rhythms and cadences and sounds have a lot in common with the spoken language. She writes in fusha, sometimes called “standard” Arabic, but her style shares many features of the vernacular: she doesn’t use ten-dollar words, her syntax is typically straightforward, economy is a virtue. She also uses tonal effects—sarcasm, for example—that we tend to associate with speech.

We talked a lot about “A grave I’m about to dig.” I’m still not sure Iman likes my choice of “diagonal” for the Arabic ma’ilan, to describe the way a bird falling out of the sky might appear to an observer on the ground (but that’s how I think of Iman: she sees things at a slant). The last phrase of the poem, “were it not for the sneakers on my feet” is a typical moment of self-deprecation, a comedy of casualness. There are no feet in the Arabic original, however, which just says “were it not for my sneakers” (or, more literally, “my sports shoes”). I thought adding the phrase “on my feet” was needed, both for musical reasons and because it suggests a pun that isn’t available in Arabic, where verse meters aren’t called feet. For me, Iman’s (musical, metrical) feet really do wear sneakers: they’re quick and agile, casual but spiffy. They’re what we wear today.

SE: Iman’s poems typically take on different forms as well as registers–at times indulging in the lyric, and at times sacrificing it for the sake of a more restrained, almost academic language. She recently told me that she believes poems don’t have “forms” as much as “personalities.” Do you find you have to “get to know” a poem of hers before you approach a translation? If so, what does that process look like?

RC: I think translation is the process—or a process—of getting to know a poem. My first versions tend to be awkward, formal, overly reliant on obvious equivalents (something like the French faux amis). That isn’t so different from the way one talks with a new acquaintance: conventions can be useful. It’s only later, and gradually, that you begin to see what makes the poem—if it’s a good poem—worth spending time with.

SE: Finally, can you tell us a little bit about the choice of title for your forthcoming collection, The Threshold?

RC: “The threshold,” in Arabic al-‘ataba, is an important motif in several of Iman’s poems. It names a site of risk, guilt, transformation. It’s also the title of a long poem that comes at the midpoint of the collection. To my mind, this is Iman’s farewell to the era of her youth. It’s a valedictory poem about Cairo in the nineties, full of Europeanizing elites, posturing poets, and entitled State intellectuals. It’s a poem of the open road that also tells the story of a generation: Iman and her friends wend their way from the Opera House in Zamalek, Cairo’s poshest neighborhood, to the ministry buildings and bars of downtown, through the streets of Old Cairo, and out into the City of the Dead—a burial ground that’s also a point of departure.

–

Robyn Creswell teaches Comparative Literature at Yale University and is a consulting editor for poetry at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is the author of City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut, and a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books.

THREE POEMS BY Iman Mersal AND INTERVIEW WITH Robyn Creswell

POEMS INTERVIEW

Iman Mersal is the author of five books of poems and a collection of essays, How to Mend: Motherhood and Its Ghosts. In English translation, her poems have appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Review of Books, The Nation, and elsewhere. Her most recent prose work, Traces of Enayat, received the Sheikh Zayed Book Award in 2021. She is a professor of Arabic language and literature at the University of Alberta, Canada. Photo credit: Hamdy Reda

Robyn Creswell teaches Comparative Literature at Yale University and is a consulting editor for poetry at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is the author of City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut, and a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books. Photo credit: Annette Hornischer

- Published in home

ISSUE 24

POETRY

EVERY SEVENTEEN YEARS CICADAS RUPTURE THE EARTH by Hannah Corrie

A STORY ENDING WITH AN OFFERING by Willie Lin

TWO POEMS by Meredith Nnoka

TENDING GRIEF AT THE GREAT SALT LAKE, A RITUAL by Kathryn Knight Sonntag

WHOEVER IS NOT HOME GROWS SICK by David Keplinger and Bruce Bond

AFTERMATH by Robert Wood Lynn

LOVE POEM WITH A MAGGOT INFESTATION by Janelle Tan

TWO POEMS by Helena Mesa

ROAD TO BYBLOS by Madeleine Cravens

IN THE HALL OF THE MOUNTAIN KING by Majda Gama

THE FAMILY STONE by Catherine Norris

FICTION

MEMORY FIELDS by Liz Howey

THE LEAST AMERICAN FACE by M. Y. Li

- Published in All Issues, Recent Issues

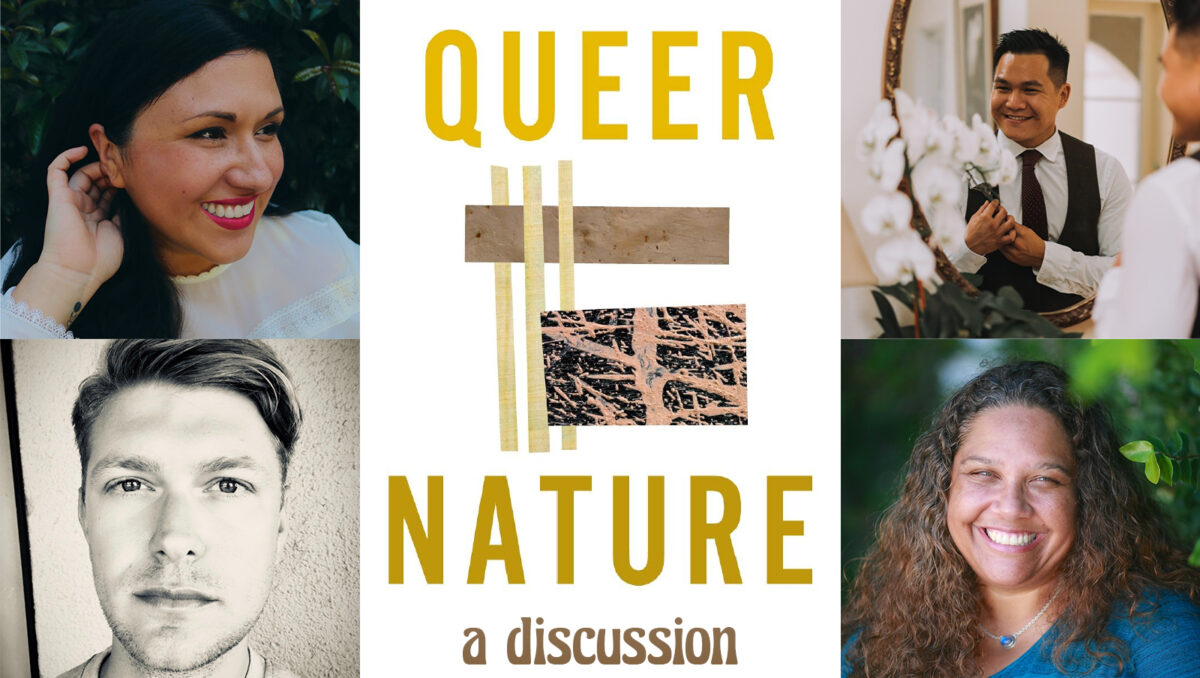

QUEER NATURE ROUNDTABLE

In 2021, Four Way Review partnered with several other journals and presses to establish the Bootleg Reading Series. It was a partnership we hoped would continue to grow beyond the reading series and lift up the projects of each partner. We’re excited to share this conversation with some of the poets of the new Queer Nature anthology, published by Bootleg partner Autumn House Press, in conversation with one another and the ideas of “queer nature”.

“Queer Nature is a groundbreaking anthology of more than 200 LGBTQIA+ poets writing about nature. Left out of the canon but with much to say, these writers peculiarize bodies into landscapes, lament the world we are destroying, and sing of darkness and love, especially along the beach. If nature is a monocrop, no single aesthetic, attitude or voice defines these poems from three centuries of American poetry.”

Michael Walsh, editor of Queer Nature, is a 2022 Lambda Gay Poetry Finalist. He received his BA in English from Knox College and his MFA in Creative and Professional Writing from the University of Minnesota—Twin Cities.

FWR: Which queer poets have inspired you? Which queer poems? If any are pastoral, do you notice anything new about them in the context of queer nature?

“You know, I have a lot of embarrassment about being pretty under informed about poetic movements or styles. I studied English and creative writing, but thought more about individual poems. This is just to say I’m not certain I understand what the pastoral is, but I do love a lot of poems that figure and transfigure the natural world. I think of poems like “Tiara” by Mark Doty, which puts drag queens next to lush water, next to death and sex.”

Eric Tran earned his MFA from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and is the author of Mouth, Sugar, and Smoke (2022), forthcoming from Diode Editions in the spring, and The Gutter Spread Guide to Prayer (2020), from Autumn House Press. He is also an Associate Editor for Orison Books and a resident physician in psychiatry at the Mountain Area Health Education Center.

“I consider poets like Elizabeth Bishop and Audre Lorde to be major influences in my development as a poet. I was introduced to both poets in college and graduate school. My first attempts to write about my own queer experience were influenced by “The Shampoo” by Bishop, in which the simple act of washing her lover’s hair inspires an image of shooting stars, suggesting to my young mind that love between two women is such a revelation that it compels images of heaven. The movement toward metaphor in this poem was indicative of the deep nature of a sexual relationship between two women. I experienced the same sense of revelation in Lorde’s “Love Poem” where intimacy pushes the speaker toward seeing her lover’s body as a forest and her own entry into it as the wind, as she opens widely to “swing out over the earth over and over again.” As an imagistic writer, I struggled to write about sex in an overt way; however, the metaphor invites great possibilities for writing about intimacy between women.

“Neither of these poems is pastoral; however, you ask an interesting question in the context of environmental poetry. Much of the nature poetry being written today is a movement away from pastoral writing. There is too much that stands in the way of the effort to ‘touch’ God through one’s experience of nature—abuses of the land, water, and air, not to mention our current focus on the power of place where the land itself has connection to indigenous peoples and histories that far more important to acknowledge, at least in my mind.”

Amber Flora Thomas earned her MFA at Washington University in St. Louis and is the author of Red Channel in the Rupture (2018) from Red Hen Press, The Rabbits Could Sing (2012) from the University of Alaska Press, and the Eye of Water (2005) from the University of Pittsburgh Press, which won the 2004 Cave Canem Poetry Prize. She is also the recipient of the Richard Peterson Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize from Rosebud magazine, and the Ann Stanford Poetry Prize.

“My poetry would not exist without the poems of [Constantine] Cavafy; his dreamy stagings of sex and history are always close to me; his frankness and the undramatic way his poems unfold have taught me so much about managing energy in short lyrics. James Merrill was the first poet I loved unreasonably. Henri Cole and Carl Phillips are two poets of my parents’ generation whose work has been indispensable to me from the beginning. They are both represented with brilliant poems in the Queer Nature anthology—both poems in some way about the way we look to the natural world to teach us about ourselves, our desires, and how the natural world always complies and refuses us at the same time.”

Richie Hofmann is the author of A Hundred Lovers (2022) from Alfred A. Knopf, and Second Empire (2015), from Alice James Books. He received his MFA at John Hopkins University and is a Jones Lecturer in poetry at Stanford University.

“The queer poets and academics whose work has been foundational in critiquing Western constructions of Nature (and thus The Human) in my work are Sylvia Wynter, Katherine McKittrick’s Demonic Grounds, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson’s Becoming Human, Gloria Anzaldua, Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem, Vievee Francis’ Forest Primeval, Jake Skeets’ Eyes Bottle-Dark and a Mounthful of Flowers, and Natalie Diaz’ Postcolonial Love Poem.

“These works reveal how the “Nature” of the Western imagination is an inherently colonial concept. “Nature” conceived as terra nullius, or empty “virgin” land, by using the very word, invents the land as an unpeopled, undisturbed habitat outside of time, removed from the urban, and evacuated of Blackness, indigeneity, and queerness. National parks—“America’s Best Idea”—are racialized spaces defined by the absence of race, and serve to dehistoricize the land from its indigenous history and frame conservation as a value rooted in rugged individualism and self-sufficiency. In the construct of “nature,” indigenous people are confined to prehistory—if nature is prehistoric, then what we do to it does not affect our future. In the Western imagination, “Nature” is separate from us, just as the body is separate from the mind, and becomes an object—a place to go, a thing to be experienced, a resource to extract from—rather than a living being surrounding us, full of beings with whom we share a destiny. The concept of “Nature” is primitive, and necessary to construct the (white, Western) Human who has evolved beyond it.”

Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, author of award-winning Beast Meridian (2017) from Noemi Press and essay collection CHUECA, forthcoming from Tiny Reparations Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, in 2023. She is a recipient of a 2021 National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship and PhD candidate at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

I think animals abound in queer poems as metaphors, false or correct, of fully living in a body.

FWR: Queer desire carries an inherent subversion of expectation, and with it, potentially, greater freedom of form and image. What are “the birds and the bees” of queer erotic poems? What metaphors are found in the biomes of queer poems, especially sexy ones?

AFT: I have been trying to find my own answer to this question. I have written about my experiences as a child of retreating to the woods as a place of safety. Often, I would find myself hiding in the woods where I could watch my family, seeing through the trees a world that could not embrace my queerness. I take my queerness to the woods where it is not moralistically judged by the trees or other flora. This question reminds me of Carl Phillips poetry and essay, especially his “Beautiful Dreamer” chapter in The Art of Daring, which describes stumbling on three men having sex against a tree in the woods. Perhaps the wilderness provides cover or separation from societal judgement, which is why we have so much to say about queerness and nature.

VAV: Nature was never accessible to me growing up—I was born on the US/Mexico border and grew up in Houston, Texas, an ever-sprawling, drowning city under construction where Nature is at least an hour drive away near the state prison, and where white flight takes its suburbs and fells trees to make room for endless strip malls and megachurches.

Still, nature asserted itself in surprising and subtle ways in the Black, Latine, and queer neighborhoods of Houston where I grew up. My childhood home is near Acres Homes—a historic Black homestead nestled between highways, famous for its barbecue and horse-mounted Black cowboys; I attended Pride at seventeen and got my first HIV test at the free clinic in Montrose, the (now fully-gentrified) historic gayborhood of Houston along Buffalo Bayou; I biked through the white-oak-lined side streets of Third Ward, Houston’s historic Black neighborhood, to attend the University of Houston. And as a child, the swampy young pines behind our house haunted my imagination and stayed with me long enough to inspire the inner nightlands of Beast Meridian.

Those pines were where I escaped the confines of gender and jumped my bike over ditches with boys, smoked cigarettes and listened to music with the bad kids, escaped angry parents to read The Bell Jar under honeysuckle, tagged anarchy symbols under bridges, explored flooded creeks and caught crawfish when the power was out after hurricanes, kissed and touched and undressed with every gender under the stars. After I got caught sneaking out at thirteen, my parents took my bedroom door off its hinges permanently, so throughout adolescence, the pines were the only place I had any privacy, the place where I became brave, the place that held my forbidden self, a sanctuary of desire that made safe my secrets, the moonlit clearing where young love blossomed in my body, a haven for a young girl in trouble to hide. My girl, my girl, don’t lie to me, tell me where did you sleep last night / In the pines, in the pines, where the sun don’t ever shine, I would shiver the whole night through. That vision of nature informs every poem in Beast Meridian, from “Malinche” to “Girlbody Gift” to the final sequence, “The Way Back”—the nightlands of forbidden desire, rebellion, trouble, alienation—where the speaker grieves her monstrosity until she can finally embrace her animal, and in so doing, sets herself free.

Queer nature is a catapult out of the limits of a single human body. It is a breaking out, a widening into the possibilities of a transformative understanding of boundaries of self.

RH: Being queer, I think, forces one deeply into one’s body—you become more aware than other people about the arbitrariness of gender and the randomness of having a body. I think animals abound in queer poems as metaphors, false or correct, of fully living in a body. Free from desire and emotional pain, social torment, strictures of marriage and morality. In my own poem, “Idyll,” the speaker desires to shed his skin; the act of speaking, of confessing to desire, is an act of undressing.

ET: I love this definition of queer. I think sometimes we think of queer as undoing or transforming, but often I think of queer as revealing what has always been. Rather than leaps, I think of sinking deeper into, of falling, of lying and pressing (as fingers into the soil)–all of which are unsurprisingly very sexy actions to take.

FWR: What does queer nature mean to you? If you experienced the HIV/AIDS pandemic, has experiencing the Covid-19 pandemic caused you to consider “nature” more than in the past?

RH: This is a hard question for me. I feel somewhat ambivalent about both “queerness” and “nature.” I don’t think of myself as a pastoral poet. I’d rather be in a museum than in a forest. But reading Queer Nature, I feel such a profound kinship with writers I’ve never met.

AFT: Queer nature is a catapult out of the limits of a single human body. It is a breaking out, a widening into the possibilities of a transformative understanding of boundaries of self.

I don’t have much to say about the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the Covid pandemic. It angers me that most people still think of HIV/AIDS as a ‘gay’ disease. Most people do not see the parallels. Most people can’t get to the point where they see how greed, environmental degradation, and ignorance lead to pandemics.

the act of creation is forever fused with subversion in nature

VAV: The nature of my youth was not the normative Nature of national parks or state reserves—it was a nameless, swampy half-acre of undeveloped land behind our house, where flooded ditches gouged the boundary between our neighborhood and the trailer park next door. That nature was where the “bad kids”—the troubled kids, rebels, outcasts, queer kids—found each other, not recognizing that our bond was not in our badness, but in shared trauma and alienation. The only way to get to our nature, queer nature, was to be disobedient, daring enough to break a rule, stay out after hours, trespass, know where to jump the fence. The forbidden places I went to skip school, smoke cigarettes, skinny dip, drop acid, give and get head, kiss both girls and boys, fuck in cars until police pulled up, were also where I went to read, write, and play guitar. And this has had a fundamental influence on my artistic practice—the act of creation is forever fused with subversion in nature. Nature and art are sites of disobedience, rebellion, and provocation—if I am not being subversive, vulnerable, provocative, brave, then I am not making the art I want to make.

Now in single motherhood, I live near Griffith Park and Southern California beaches, and nature is a haven from isolation and endless responsibility, an expansive companion that quiets my troubled heart, holds my grief in rosy light, and sends me guardians to guide my path—still deer, scrappy coyotes, vigilant owls, hovering hummingbirds, tumbling dolphins, fragrant artemisia—their presence urging me to go on when the world feels impossible and love never comes. Now, nature is where I go to slow down time and listen to the open, be with when there is no one, be with until there is.

ET: I think queer nature asks about access and owning and belonging. I think in both of these epidemics, we had to reckon with the truth that very little is owed to us and in fact, we are obligated to return our bodies to the natural world eventually. That sounds very bleak but what I mean is that my idea of queer nature is to be freed of invented obligation and restriction and to discover and experience what is opened.

ISSUE 23

POETRY

SELF PORTRAIT AS MINOTAUR by Kiyoko Reidy

AN ORDINARY WEAKNESS by Mikko Harvey

TWO POEMS by Xochiquetzal Candelaria

DER KLEINE KATECHISMUS by Constance Hansen

CALLS TO ORDER by Stephanie Kaylor

& LORD KNOWS by Kwame Opoku-Duku

TWO SECTIONS FROM “THE BREAKUP” by Mag Gabbert

THE STATE BIRD OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE by Matthew Tuckner

CENTO FOR LONGING by Rage Hezekiah

ARS MORIENDI (FOR JEFF BEZOS & ELON MUSK) by Benjamin Aleshire

TWO POEMS by Perry Janes

FALL by Joshua Garcia

MOVEMENT by Brett Hanley

FICTION

THE GAIN by Jennifer Solheim

THE APPARENT PATH by Casey Guerin

ART

- Published in All Issues, Issue 23, Recent Issues

BOOTLEG READING SERIES

- Published in home

ISSUE 22

POETRY

TWO POEMS by Aaron Coleman

chances are by Denise Duhamel

OFFERING by Mike Puican

TWO POEMS by Mark Smith-Soto

WIDOW, WALKING by Betsy Sholl

TWO POEMS by Katie Pyontek

FIVE POEMS by Kenneth Tanemura

TWO POEMS by Michael McFee

PEGASUS TATTOO ON THE LEFT by Jai Hamid Bashir

POST-IMPAIRMENT SYNDROME by Victoria C. Flanagan

GATE by Grayson Wolf

SYRIAN CHEMICAL WEAPONS STRIKE, DOUMA, APRIL 2018 by Brian Russell

FICTION

SLUSHIE by Shyla Jones

CALVIN AND CALVIN by John West

Odium by Ilya Leybovich

THE SWING OF THINGS by Becky Hagenston

- Published in All Issues, Recent Issues

ISSUE 21

POETRY

BECAUSE I MAKE MYSELF NEW EACH DAY by Rebecca Macijeski

AND WE TRY TO FIND GESTURES FOR OUR HUMANITY WHEN WE’RE YOUNG by Rodney Terich Leonard

THE HOUR OF THE WOLF by David Roderick

THREE POEMS by Sarina Romero

FIVE POEMS by Amorak Huey

TWO POEMS by Augusta Funk

TWO POEMS by Irène Mathieu

GYM CRUSH by Josh Tvrdy

WHEN SUN SHINES ON WATER by Stella Lei

ANOTHER OHIO ROAD TRIP by Erika Meitner

COME CORRECT by Erika Meitner & Traci Brimhall

TWO POEMS by Hussain Ahmed

FICTION

LOVE AND LEAVING IN THE CONDITIONAL by K-Yu Liu

EGG WISHES by Lucy Zhang

DON’T CALL ME YOUR PRINCESS by Megan Culhane Galbraith

AWAKE UNTIL DAWN by Pete Prokesch

ART

- Published in All Issues, Issue 21, Issues

MONTHLY: Chapbook Conversation

The chapbook is a strange and protean form, flickering somewhere between long poem and short book, and though they get little love from reviewers, prize committees and large publishers, many of us write, publish and love them. So, in January, I sat down with three poets whose chapbooks I’ve really enjoyed, to talk with them about our experiences writing (and shilling for) these little fascicles, and how we did (or did not) weave them into full-length books. Conor Bracken

Conor Bracken is the author of Henry Kissinger, Mon Amour (Bull City Press, 2017), selected by Diane Seuss as winner of the fifth annual Frost Place Chapbook Competition, and The Enemy of My Enemy is Me (Diode Editions, June 2021), winner of the 2020 Diode Editions Book Prize. He is also the translator of Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s Scorpionic Sun (CSU Poetry Center, 2019). His work has earned fellowships from Bread Loaf, the Community of Writers, the Frost Place, Inprint, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and has appeared in places like BOMB, jubilat, New England Review, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and Sixth Finch, among others. He lives with his wife, daughter, and dog in Ohio.

What the Chapbook Allows For

“[The chapbook was] a more dense approach. [The poems] are more focused… Because I am so blobular and sprawly…the chapbook helped me so much with the [full length] book… You know when cells sort of… create an internal circle and expel something? Endocytosis! This little nucleus started forming within the blob [of a bigger idea], and that became the chapbook. That helped me center around a specific object, and a specific line of thought, and it became a guiding principle. A concrete thing to work around. [The chapbook] helped me in eliminating all the things that did not belong to it.” Ananda Lima

Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land was the winner of the 2020 Hudson Prize and is forthcoming in 2021 (Black Lawrence Press). She is also the author of the poetry chapbooks Amblyopia (Bull City Press – Inch series, 2020) and Translation (Paper Nautilus, 2019, winner of the Vella Chapbook Prize), and the fiction chapbook Tropicália (Newfound, forthcoming in 2021, winner of the Newfound Prose Prize). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark.

Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land was the winner of the 2020 Hudson Prize and is forthcoming in 2021 (Black Lawrence Press). She is also the author of the poetry chapbooks Amblyopia (Bull City Press – Inch series, 2020) and Translation (Paper Nautilus, 2019, winner of the Vella Chapbook Prize), and the fiction chapbook Tropicália (Newfound, forthcoming in 2021, winner of the Newfound Prose Prize). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark.

“For me, too, [the chapbook] was so much more fun…! The chapbook is just a really wonderful time. It’s really one of my favorite parts of my writing life so far.” Taneum Bambrick

Taneum Bambrick is the author of VANTAGE, which won the 2019 APR Honickman First Book Award. Her chapbook, Reservoir, was selected for the 2017 Yemassee Chapbook Prize. A graduate of the University of Arizona’s MFA program and a 2020 Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, her poems and essays appear or are forthcoming in The Nation, The New Yorker, American Poetry Review, The Rumpus and elsewhere. She teaches at Central Washington University.

Taneum Bambrick is the author of VANTAGE, which won the 2019 APR Honickman First Book Award. Her chapbook, Reservoir, was selected for the 2017 Yemassee Chapbook Prize. A graduate of the University of Arizona’s MFA program and a 2020 Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, her poems and essays appear or are forthcoming in The Nation, The New Yorker, American Poetry Review, The Rumpus and elsewhere. She teaches at Central Washington University.

“There was something more fun about the chapbook process, because it almost felt like you didn’t know what the expectations were… Because the big book is like “This is the BIG BOOK… Oftentimes we’re so used to seeing our poems in our Microsoft Word frame-world, that it was such a huge thing to me when Ross sent me my first mockup of my book… Going through those small processes, having the object, giving your first reading with the book, and going through all those on a smaller level, to me was such an added boost in getting to the big book process.” Tiana Clark

Tiana Clark is the author of the poetry collection, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018), winner of the 2017 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize, and Equilibrium (Bull City Press, 2016), selected by Afaa Michael Weaver for the 2016 Frost Place Chapbook Competition. Clark is a winner for the 2020 Kate Tufts Discovery Award (Claremont Graduate University), a 2019 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, a recipient of a 2019 Pushcart Prize, a winner of the 2017 Furious Flower’s Gwendolyn Brooks Centennial Poetry Prize, and the 2015 Rattle Poetry Prize. She was the 2017-2018 Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing.

Structure

“I looked at each of the sections of my big book as actually three different chapbooks. And that helped me break down the aerial view into sizeable chunks to help me manage it mentally and emotionally.” TC

“I’m writing these poems and then I see that there’s a sort of theme emerging, and there’s a lot of poems that are talking to each other and are tending towards certain subject matter or a mood. At first I’m just thinking of the poem as a poem, and then I’m thinking of this blob… This is my book—the blob!

For me, the difference between the blob and the chapbook was just that there was a conversation crystallizing around this nucleus… Find and create bridge poems: Look for poems you might have thought about including in your chapbook, but decided not to because they veered away from the chapbook’s core. You can also do this with new work, work-in-progress, and even notes on poems-to-come. The goal is to find poems that speak to the work in the chapbook, but don’t neatly fit into it. Use that intersection to expand the work into new threads to be explored for the full length.” AL

“Think about your favorite book of poems. There’s probably only 5 or 6 poems that come to your head… If you have 5 or 6 fire poems, then you’re ready to go… Also…make sure everything looks beautiful and perfect. It starts from the table of contents. Those are like little chapter novels!” TC

“What do you feel is missing? I don’t mean “missing” in a negative way, but rather as gaps where more risk, information, and urgency might enter into the project. What did you carve out through the editing process? Do you still have those drafts? Who told you to throw them away? The process of editing a chapbook, at least for me, was so influenced by institutions: some of what I removed initially, or didn’t feel brave enough to pursue, were poems and essays that represented the most authentic parts of the experiences I was describing.” TB

Audience

“Thinking about the audience in the process of composition and even assemblage can be paralyzing. I love how chapbooks can unfetter us from our own expectations of ourselves so that we can write without an audience, that doesn’t even exist, breathing down our necks…and can also give us this kind of tailwind we need for the next stage.” CB

“I did a mini-chapbook tour…and I was reading at mostly bars in random places…and I was just writing down questions people had for me, so I would hear where the gaps were, [the] places where I was resisting something that felt risky or where I hadn’t written yet something that might be the most vulnerable.” TB

“I often don’t think about the audience, even in general. I saw Terrance Hayes in an interview talk about how in his first drafts the audience is never in the room, it’s just [him]and [his] shadows and [he’s]just exorcising everything out. Obviously, we think about the audience at some point, which for me is revision, or publication. I always tell my students there’s the poems you write and the poems you publish.” TC

“Using submissions as a thing in your writing process …is very true for me too. I find that the revisions I do before the deadline are so much better than the ones I’ve been doing for months. That’s when the audience comes in… It makes it easier to imagine other eyes reading that.” AL

Submitting

“I was unable to publish the poems individually because my book is very much narrative-driven, so if you extract individual parts, they don’t really make sense. I was encouraged by my workshop leaders at the University of Arizona to pursue chapbook publication.” TB

“[The thought process was] I think I have 15-20 poems in conversation, let me submit to a chapbook competition. I make it sound so haphazard but that’s kind of how I was… I looked at submission deadlines at the time as a way for me to help with my revision process.” TC

“Having that editing process helped me understand what I had here [in this chapbook] that belonged to the other [bigger] book.” AL

“I got a handwritten rejection from Bull City. It was so cute! I remember carrying that handwritten note around. I had it on my wall in my room because it was so important to me. It was the first time anywhere that I considered to be a really big deal publishing place had ever spoken to me. It was this intense breakthrough that gave me the motivation to submit it… I look back on how dramatically that changed my idea of myself. From that note on, I went from writing by myself to writing in community.” TB

“If you got a personal rejection, whether that’s for an individual submission or for a chapbook or for a big book prize…the fact that someone took the time is a really big thing, and it’s also a sign you’re getting closer. I love that quote from Sylvia Plath: ‘I love my rejection letters, they’re signs that I tried.’” TC

How much of the chapbook became ‘the Big Book’?

“When it got to the Big Book for me, [the big book] definitely had a theme…after you do the mini-tour [for the chapbook] and get the little amuse-bouche of what’s happening, then it helps you for the Big Book. I was like, what conversations do I want to be having, what do I want to answer in Q&As and interviews, because I got a taste of that with the chapbook… [For the chapbook and the big book] I let those voices haunt me in a different way.” TC

“[I had] my fears about having too many of the same poems in the chap and the full-length, and worrying about the audience in that way and trying to figure out how to make [the poems] different. I ended up with almost all the poems from my chapbook in my full-length, so that felt like a really big risk… My chapbook had a quieter reception, so it didn’t really matter that much. But the biggest difference is that I was really interested in hybridity and including essays alongside poems… The difference between the chapbook and my book is pretty much the risk of hybridity and the risk of engaging in those traumatic, scarier, more personal details.” TB

“I was worried that everyone had read some of these poems. Because it felt like more of a book than a chapbook for me, I kind of let it go. “This is its own thing.” The full-length became a challenge of creating a newer object and I want them to have two separate worlds. I think I only have 2.5 poems…from the chapbook in the big book. What are poems that are absolutely in this other conversation? But I gave myself permission to let my chapbook be its own thing and just kind of put it on a boat and pushed it away.” TC

Direct Advice

“What are some guiding principles? ‘Every good book—whether that be a novel, a linked short story collection, or a sequence of poems—starts with an unanswerable question.’ And the protagonist…struggles with that, trying to answer that question, and never does, but it’s that tension that creates the narrative arc.” Charles Baxter via TC

“Having good teachers is really important for [learning to embrace risk] and identify what [you’re] avoiding.” TB

“The workshop is a voice but not the voice. [It can] sanitize risk.” TC

“One thing my professor [Mark Jarman told me about impostor syndrome], this grand professor with all these books, he was like “oh, you’ll have that for the rest of your life.” He said it so matter-of-factly and there was something about that that was so comforting, so I was like oh, so this is not something to overcome and the fact that I’m feeling that is very much in line with being a writer. Once I realized it was insurmountable, I was like oh, I got this. So I alchemized that energy.” TC

“Find unexplored threads in your chapbook: Talk through your poems with a generous friend (or an imaginary friend, if you are good at pretending). Go through each of the poems in your chapbook and have fun geeking out on what you did (eg. “the line break here does X, isn’t that cool?”, “I used this word here because it can also mean X,” etc). Sometimes talking about poems in the way, you find themes that are under the surface, that you could explore them in more depth in a full collection. The friend can stay silent or they can ask questions (eg. “where do you think this word is going?”), as long as you both understand that this is not a workshop but a generative exercise looking for nascent threads in the chapbook.

[In terms of emotional management] Feel great about yourself and your accomplishment. You wrote a chapbook and that is awesome. Remind yourself when you didn’t have a chapbook at all and the time when you were anxious about a fledgling something in your hands, unsure of where it would go. Remember this and use it to keep yourself going through some similar anxieties when writing your full-length collection.” AL

- 1

- 2