FEBRUARY MONTHLY: INTERVIEW with CLAIRE HOPPLE

From the first sentence of Claire Hopple’s latest novel, Take It Personally, you know you’re in for a ride—in this specific case, you’re sidecar to Tori, who has just been hired by a mysterious and unnamed entity to trail a famous diarist. Famous locally, at least. What sort of locality produces a “famous diarist”? One whose demonym also includes the nearly equally renowned Bruce, made so for his reputation of operating his leaf blower in the nude, of course. And that’s just the beginning. Take It Personally follows Tori as she follows the diarist, Bianca, determined to discover whether her writings are authentic or a work of fiction. At least, until Tori has to go on a national tour with her rock band, Rhonda & the Sandwich Artists, who are, as Tori explains, right at the cusp of fame. It is a novel as fun as it is tender, filled with characters whose absurdity only makes them more sincere.

Claire Hopple is interviewed by E. Ce Miller.

*

FWR: It seems like much of your work begins with absurd premises. The first line of Take It Personally is, “Unbeknownst to everyone, I am hired to follow a famous diarist.” This quality is what first drew me to your fiction, this sort of unabashed absurdity. But then you drop these lines that are absolutely disarmingly hilarious. You’re such a funny writer—do you think of yourself as a funny writer? What are you doing with humor?

CH: Thank you! That is too kind. I’m not sure I think of myself as a funny writer, or even a writer at all––more like possessed to play with words by this inner, unseen force. But I think humor should be about amusing yourself first and foremost. If other people “get it,” then that’s a bonus, and it means you’re automatically friends.

FWR: In Take It Personally, as well as the story we published last year in Four Way Review, “Fall For It”, many of your characters have this grunge-meets-whimsy quality about them. They seem to have a lot of free time in a way that makes me overly aware of how poorly I use my own free time. They meander. They follow what catches their attention. They are often, if not explicitly aimless, driven by impulses and motivations that I think are inexplicable to anyone but them. They seem incredibly present in their immediate surroundings in a way that feels effortless—I don’t know if any of them would actually think of themselves as present in that modern, Western-mindfulness way; they just are. In all these qualities, your characters feel like they’re of another time—unscheduled, unbeholden to technology. Perhaps a recent time, but one that sort of feels gone forever. Am I perceiving this correctly? Can you talk about what you’re doing with these ideas?

CH: I’ve never really thought about them that way, but I think you’re right. And I think my favorite books, movies, and shows all do that. We’re so compelled to fill our time, to make the most use out of every second, and it just drains us. There’s a concept I heard about recreation being re-creation, as in creating something through leisure in such a way that’s healing to your mind. We could all stand to do that more. Hopefully these characters can be models to us. I know I need that. But reading is an act of slowing down and an act of filling our overstimulated brains; it’s somehow both. So maybe it’s just a little bit dangerous in that sense.

FWR: Are you interested in ideas of reliable versus unreliable narrators, and if so, where does Tori fall on that spectrum? She’s a narrator presenting these very specific and sometimes off-the-wall observations in matter-of-fact ways. I’m thinking of moments like when Tori’s waiting for the diarist’s husband to fall in love with her, as though this is an entirely forgone conclusion, or the sort of conspiratorial paranoia she has around the Neighborhood Watch. She also “breaks that fourth wall” by addressing the reader several times throughout the book. What are we to make of her in terms of how much we can trust her presentation of things? What does she make of herself? Does it matter if we can trust Tori—and by trust, I suppose I mean take her literally, although those aren’t really the same at all? Do you want your readers to?

CH: All narrators seem unreliable to me. I don’t think too much about it because humans are flawed. They can’t see everything. For an author to assume that they can, even through third-person narrative, achieve total omniscience in any kind of authentic voice seems a little bit ridiculous. But I’m not saying to avoid the third person, just to not take ourselves too seriously. I hope that readers can find Tori relatable through her skewed perspective. She views the world from angles that give her the confidence to continue existing. They don’t have to be true in order to work, and I think a lot of people are operating from a similar mindset, whether they realize it or not. We can trust her because she’s like us, even––and maybe especially––because she’s not telling the whole truth.

FWR: Take It Personally is a novel I had so much fun inside. I read it in one sitting, and when I was finished, I couldn’t believe I was done hanging out with Tori. From reading your work, it seems you’re having the time of your life. Is writing your fiction as good a time as reading it is?

CH: It means so much to me that you would say that. Seriously, thank you. Yes! Reading and writing should be fun. I’m always confused by writers who complain about writing. If they don’t like it, maybe try another hobby? I secretly love that nobody can make money as a writer in our time because it means writing has to be a passionate compulsion for you in order for you to continue.

FWR: You’re the fiction editor of a literary magazine, XRAY. Does your editing work inform your writing and publishing life? How do you see the role of lit mags in this whole literary ecosystem we’re all trying to exist in?

CH: Lit mags are crucial. They’re some semblance of external validation, which everyone craves. But what we’re doing, whether intentionally or unintentionally, is creating a community. We’re only helping each other and ourselves at the same time.

FWR: It is a strange time to be a writer—or a person, for that matter. (Although, has this ever not been the case?) As we’re holding this interview, parts of the West Coast of the United States are actively burning to the ground. Other parts of the country are or have very recently been without water. I know you directly witnessed the climate disaster of Hurricane Helene last year, which devastated many beloved communities in the mid-Atlantic, including the wonderfully art-filled city of Asheville. How are you making space for your writing in all this? How are you able to hold onto your creativity amid so many other demands competing for time and attention?

CH: Completely agree with you here. Things are a mess. Our climate is barely hanging on. There were several weeks where I couldn’t really read or write at all; the whole thing felt like some ludicrous luxury. I was flushing toilets with buckets of creek water. But now that my head has finally cleared, I’m able to realize their importance again. Great suffering has always produced great art and hopefully points us to a better way of living. It just might take time, recovery, patience, and perspective to develop that. Some of my favorite paintings and books were a direct result of artists’ personal experiences at the bombing of Dresden in WWII. How weird is that? We have to make time for art, but not in some sort of shrewd drill sergeant kind of way. We have to fight for it, make space for it, recognize that it’s just as important as whatever else is on the calendar. Recognize that it’s a form of therapy. And we have to feel so compelled to create that it’s happening whether we even want it to or not.

- Published in Featured Fiction, home, Interview, Monthly

JUNE MONTHLY: In Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Nearly a year after the October 7 Hamas terrorist attack and Israel’s subsequent escalation of a decades-long project of state-sponsored genocide of the Palestinian people, Gaza continues to face deadly bombings and attacks from Israel. According to Gaza’s Health Ministry, the death toll of Palestinians is in the tens of thousands, with no sign of Israel relenting.

In response to the death and destruction in Palestine, Barricade and Four Way Review joined together to raise the voices of Palestinian poets and others from around the world standing in solidarity with them. While we stand fervently against Anti-Semitism, we also resist its false equation to anti-Zionism; we equally condemn Islamophobia, anti-Arab racism and xenophobia, and imperialism, all of which function together to murder and oppress the poor and working classes and to legitimize expropriation and forced displacement.

The poems you will read here have been previously published in Barricade and represent a desire to use our platforms to uplift and disseminate translations from and in solidarity with Palestinians. Barricade shares contributions on its forum Ramparts, a makeshift oppositional online space founded on the basis of urgency and necessity; Four Way Review has compiled a selection of Ramparts posts here, with the aim of expanding the reach of these writings and giving them a more permanent home.

Four Poems, Olivia Elias (trans. Jérémy Victor Robert)

SLUMROYAL, Yahya Hassan (trans. Jordan Barger)

Urgent: News of the Death of Hiba Abu Nada, João Melo (trans. G. Holleran)

- Published in Monthly, Poetry, Translation

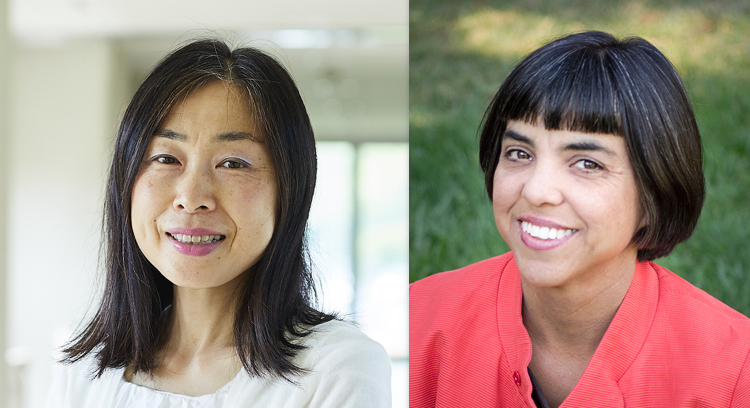

ECOPOETRY FROM JAPAN with Ryoichi Wago and Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FOUR POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

by Judy Halebksy

Ayako Takahashi

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FIVE POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

This folio shares recent translations from two Japanese poets, Kora Rumiko (1932-2021) and Wago Ryoichi (1968-). Kora’s poems are from the second half and 20th century, and Wago’s were written following the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown that devastated his home region. Writing in different times and from different perspectives, these poets overlap in that their writing draws attention to environmental degradation and inequality while simultaneously voicing a strong sense of place.

Kora was born and raised in Tokyo. Her childhood was shaped by the Second World War and the devastation of the Tokyo fire bombings that she witnessed as a thirteen-year-old. In the changes of the post-war era and the rapid industrialization of the 1970s, her neighborhood grew from a small community to a bustling urban area. Her writing speaks against capitalism and colonialism. At a time when many Japanese writers were influenced by European literary forms, Kora looked toward writers from Asia and Africa, all while drawing inspiration from mythology, envisioning matriarchy, and speaking to the harms and costs of nuclear weapons and nuclear power.

These themes are evident in her poem, A Mother Speaks, which is set within the Noh play A Killing Stone (Sesshôseki). Noh is a somber, serious theatre tradition that has been in living practice for more than six hundred years. Plays often have themes of connecting the dead with the living and of vanquishing evil spirits. A Killing Stone references the legend of the fox spirit and Lady Tamamo’s attempt to use her supernatural power to kill the emperor. As the story goes, her plans fails and her spirit is relegated to a stone that kills any living thing that passes over it. Kora’s poem envisions Tamamo’s power, fertility, and the potential of transformation, offering an embodied, feminist perspective on the Noh play and the legend more broadly.

Wago is a high school teacher and has lived in Fukushima prefecture his whole life. In March 2011, when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear powerplant failed, he did not evacuate, but sheltered in place in his apartment in Fukushima City, 50 miles away from the powerplant. He started a Twitter feed of thoughts and observations, which soon had thousands of followers. Pebbles of Poetry 1, from Macrh 16, 2011, marks the very beginning of his posts and the moment when people were just becoming aware of the radiation leaks. On several occasions, Wago visited areas inside the evacuation zone, a 12-mile radius of the power plant. He wore a protective suit and a radiation monitor. His poem Screening Time was written after one of those visits. Wago’s writing addresses environmental degradation with an ecopoetics that not only explores the human toll of this catastrophe, but also includes the perspectives of cows abandoned in the fields; the fruits and crops left to waste; the once vibrant towns that now stand empty; and the soil, the ocean, and the air.

January 7, 2021, is one of a series of poems that Wago wrote marking ten years since the nuclear meltdown. It voices a more composed perspective on the memories and experiences of his earlier writings. It opens with a description of flying above the evacuation zone and includes a conversation with a dairy farmer forced to evacuate the area and abandon his herd. The poem integrates quotes from Wago’s twitter feed on March 22, 2011 in the first days following the meltdown; contextualizing, in this way, the original posts, integrating them with images and details to create an immersive sense of presence. Much of Wago’s work is dedicated to restoring Fukushima prefecture, not just in terms of environmental restoration, but also of the culture and lifestyle of the region and the well-being of future generations.

Ayako Takahashi and I have translated these poems collaboratively, working together weekly over video chat since 2017. Ayako tends to favor a more literal translation, while I am often most concerned that the translations work as poems. Our hope is that we have landed someplace in the middle, maintaining with fidelity the vitality of the original works.

- Published in Interview, Monthly, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Wago, Ryoichi. Since Fukushima. Trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi. Vagabond Press, 2023. Print.

Purchase the book here.

Screening Time

November 26th, 2011

—exiting the restricted area, a 20 km radius of the power station

screening palms

screening the back of my hands

screening with my hands up

screening with my hands down

screening over my head

screening the back of my head

screening the sole of my left shoe

screening the sole of my right shoe

screening my entire body

screening what is outer space

screening what is a hometown

screening what is life

screening what is radiation

to us

what is most precious

what cannot be measured

You

(no date)

precious

you

what are you

doing now

you are me

I am you

from the obsidian depths of night

it’s you I am thinking about

and for me

from me

you

I won’t give up on

for you

I won’t give up

JANUARY 7th, 2021

I swooned

reeled

reeling.

it was spring, one year after the disaster.

I boarded a helicopter and traveled into the restricted zone,

the 20 km surrounding the nuclear power station,

high above, looking over the land below.

from a perfectly kept beach,

we crossed into the forbidden sky,

as though we were trespassing.

the land left just as it was that day.

huge, concrete wave-breaks strewn on the beach.

houses, cars, and boats hit by the tsunami, scattered everywhere.

mud and stones spread across roads and fields, electric poles keeled over.

dogs chained at front doors and left behind….

time stopped.

no.

time doesn’t exist.

I remembered that.

dizzy. still now.

could be. the aftershocks.

which continue even now, I think.

the other day, I heard a story

from a dairy farmer living within 20 km of the power station.

“the cows were so hungry

there were teeth marks all through the barn and along the fences.

until the end, trying to find something to eat.

they wasted to skin and bones then fell over…”

*

“tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, getting by. an aftershock.

tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, standing here. an aftershock.

a local broadcaster says, now everyone has heard of Fukushima. if we can recover, it’s an opportunity for us, he says. we’re known all over the world. an aftershock.

we clung to hope. tried to be grateful. is there a reward? maybe. but.

our families and our roots are here. famous around the world? I’ll burn the map.

an aftershock.

it’s calm. the night air, radiation. an aftershock.”

(March 22, 2011)

PEBBLES OF POETRY

Part 1: March 16th, 2011, 4:23 am —March 17th, 2011, 12:24 am

Such a huge catastrophe. I was staying at an evacuation center but I’ve now pulled myself together and returned home to work. Thank you for worrying about me and encouraging me, everyone.

March 16th, 2011. 4:23 a.m.

Today, it is six days since the earthquake. My way of thinking has completely changed.

March 16th, 2011. 4:29 a.m.

I finally got to a place where all I could do was cry. My plan now is to write poetry in a wild frenzy.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

Radiation is falling. It is a quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

This catastrophe is so painful, and for what?

March 16th, 2011. 4:31 a.m.

Whatever meaning we can find in all this might come out in the aftermath. If so, what is the meaning of aftermath? Does this mean anything at all?

March 16th, 2011. 4:33 a.m.

What does this catastrophe want to teach us? If there’s nothing to learn from this, what should I believe in?

March 16th, 2011. 4:34 a.m.

Radiation is falling. A quiet quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:35 a.m.

I was taught, “wash your hands before coming in the house.” But there isn’t any water for us to use.

March 16th, 2011. 4:37 a.m.

Relief supplies haven’t arrived in Minamisôma. I’ve heard that the delivery people don’t want to enter the town. Please save Minamisôma.

March 16th, 2011. 4:40 a.m.

For you, where do you call home? I’ll never abandon this place. It’s everything to me.

March 16th, 2011. 4:44 a.m.

I’m worried about my family’s health. They say that this amount of radiation won’t affect us very soon. Is “not very soon” the opposite of “soon”?

March 16th, 2011. 4:53 a.m.

Well, yes, there’s clearly a border between fact and meaning. Some say that they are opposites.

March 16th, 2011. 5:32 a.m.

On a hot summer day, I like to go to a beach on the Minami-sanriku coast. On that exact spot, the day before yesterday, a hundred thousand bodies washed ashore.

March 16th, 2011. 5:34 a.m.

In a quiet moment, when I try to understand the meaning of this catastrophe, when I try to see it clearly there’s nothing, it’s meaningless, something close to darkness, that’s all.

March 16th, 2011. 10:43 p.m.

Just now, while writing, I heard a rumbling underground. Felt the tremors. I held my breath, kneeled down, and scowled at everything swinging. My life or this tragedy. In the radiation, in the rain, no one but me.

March 16th, 2011. 10:46 p.m.

Do you love someone? If it’s possible that everything we have can be lost in an instant, then all we need to do is to find some other way not to be robbed by the world.

March 16th, 2011. 10:52 p.m.

The world has repeated both its birth and death, sustained by some celestial spirit which defies all meaning.

March 16th, 2011. 10:54 p.m.

My favorite high school gym is being used as a morgue for unidentified bodies. The high school nearby, too.

March 16th, 2011. 10:56 p.m.

I asked my mother and father to evacuate but they couldn’t stand to leave their home. “You should go,” they said to me. I choose them.

March 16th, 2011. 11:10 p.m.

My wife and son have already evacuated. My son calls me. As a father, do I have to decide?

March 16th, 2011. 11:11 p.m.

More and more people are evacuating from this town. I know it’s hard to leave. You can do it.

March 16th, 2011. 11:39 p.m.

Having evacuated to a safe place, the young man, twenty-something, is looking at the monitor and crying, “Don’t give up on our dear Minamisôma,” he says. What’s the sense of things in your hometown? Our hometown now, overcome with suffering, faces distorted by tears.

March 16th, 2011. 11:48 p.m.

Again, big tremors. The aftershocks we were expecting finally came. I was wondering if I should shelter under the stairs or just open the front door. Outside, in the rain, radiation is falling.

March 16th, 2011. 11:50 p.m.

The gas is on empty. Out of water, out of food, out of my mind. Alone in this apartment.

March 16th, 2011. 11:53 p.m.

A long rolling tremor. Let’s place our bets, do you win or do I win? This time I lost but next time, I’ll come out fighting.

March 16th, 2011. 11:54 p.m.

Until now, we carried on the daily lives of generation after generation, we searched for happiness, sincerity, I think.

March 16th, 2011. 11:56 p.m.

My elderly neighbor gave me a box full of onions. He grew them himself. Sadly, I’m not much for onions. The box sits in the entryway, I stare at it silently. A few days ago, I was living my ordinary life.

March 16th, 2011. 11:59 p.m.

12 am. Six days since the disaster. A sick joke! Six days since and for five days, I’ve wanted this all to be fixed.

March 17th, 2011. 12:03 a.m.

In the kitchen. Cleaning up scattered, broken dishes. Aching as I put them one by one into the garbage. Me and the kitchen and the world.

March 17th, 2011. 12:05 a.m.

No night no dawn.

March 17th, 2011. 12:24 a.m.

Ryoichi WAGO (1968–) is a poet and high school Japanese literature teacher from Fukushima City, Japan. In 2017, the French translation of his book, Pebbles of Poetry, won the Nunc Magazine award for best foreign-language poetry collection. Since March 2011, his writing has focused on the ecological devastation of the areas affected by the Tôhoku earthquake, tsunami, and the nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power station. Choirs across Japan sing his poem Abandoned Fukushima as a prayer for hope and renewal.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Alive, the wind

lifts seeds

and carries them away

spider eggs hatch and depart on the wind

over years the wind breaks down plants into soil

we are of the wind and all of our senses

the wind breathing

through us

Within the Trees, A Universe

-Sacred Forest of Kinabatangan, Malaysia

people listen to the trees speak

the trees heard the people

there is light in the woods there was darkness

both life and death

there are voices and so there was silence

within the woods a universe

within the trees a human becomes human

A Mother Speaks

After seeing the noh play, A Killing Stone, Sesshôseki

the play starts in Nasuno province

on the stage there’s a thick purple silk cloth

covering a stone that was dropped

over a field like a cracked rotten egg

a bird flies over the stone and drops

dead to the ground, any living thing, person

or animal that touches that stone dies

a village woman tells the story of this terrifying stone

it starts with her failed attempt to take the emperor’s life

which left her spirit captured within the stone

that now casts spells on the living

when the stone splits open

the village woman appears as a ghost

and the dead return hatching through the stone

pulsing with energy stronger than even the living

the woman’s blaring red rage steadies

and fades to a pale color

the stone again becomes an egg

the defeated become the victors

the lost become found the dead revive

she speaks, the years steal from us

we are robbed of our eggs and escape to the wilderness

we give birth to stone children

hold them in our arms warming the stone

abreast of the thieves who stole our eggs

her ghostly feet glide stamp the ground

a voice within the mask scolds us

echoing from another world

will you be ruled by this bearing always

Rumiko KORA (1932-2021) was a poet, translator, and critic born and raised in Tokyo. Her book The Voice of a Mask won the Contemporary Poetry Prize in 1988. She also wrote essays and novels and co-translated an anthology of poetry from Asia and Africa. She devoted herself to promoting women’s work and was instrumental in establishing the Award for Women Writers. Much of her writing focuses on identifying the struggles and contradictions of a female gender identity.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

INTERVIEW WITH Ayesha Raees

Ayesha Raees’ fabulist and fable-like chapbook, Coining a Wishing Tower (Platypus Press Broken River Prize winner, 2020, selected by Kaveh Akbar), is composed of 56 prose-like blocks—give or a take a few half-fragments.

These prose-poems, which are whimsical, profound, vulnerable, and full of pathos, grief, and transformation, depict complex relationships between parents and child, religion and women, lovers and the beloved, wishers and wish-granters. There are three separate narrative strands, teleporting between Pakistan; New York City; Makkah; New London, Connecticut; as well as more abstract spaces, like a Desire Path, as well as Barzakh (which, the chapbook tells us, Google calls a “Christian Limbo”).

The first narrative involves House Mouse, who climbs and climbs until the “end of all possible height” and finds itself in a wishing tower which can grant all its wishes. House Mouse performs various rituals including the ritual of death—in which both House Mouse and the tower die. The second strand, taking place in a wooden house in New Connecticut, involves three characters: Godfish, a cat who is in love with Godfish, and the moon, who is also in love with Godfish. And finally, there is the more realist narrative strand, with a female speaker—a daughter and an immigrant—who seems to speak for Raees herself, and her own personal experiences with family, religion, migration and displacement.

She is interviewed here by Cleo Qian, previously published in Issue 25.

CQ: How did you come up with the characters of House Mouse, the tower, Godfish, the cat, and the moon?

AR: Each character in the book embodies, not always wholly or too literally, a person of importance from my life. The book itself was conceived the night that I found out my best friend, Q, was in an irreversible coma due to a (eventually successful) suicide attempt. The characters in the book are my own reckoning with the different facets of the deaths we face in our lives before our eventual, more literal, ends. But I did not want this book to be so linear or literal; I wanted it to tackle death in varying ways.

House Mouse represents every young immigrant. Immigrants must leave their “selves” or “homes” for a better future, which is the mirage of the “American dream”—which calls for outsiders to come in and fill the gaps of a decaying system. Asian immigrants also, in many ways, are pressed for success or “height” to obtain ‘value’ from a very young age.

As a poet, “House Mouse” is also a play on words. What happens to a common house mouse when it is without a house? What happens to a young immigrant when they leave their homes for the world’s seductions?

The wishing tower is a symbol of the Ka’abah but is also something of extreme physical height, an unreachable thing. “Coining” in the collection’s title reflects stoning—a visual gesture, with prayers or wishes. Godfish is a play on goldfish, but this character also represents another close friend of mine, A, who was another young immigrant who left home to America to pursue another life and was lost in a tragic way. And the cat and the moon are, at the end of the day, spectators, both holding power but choosing to practice it in different ways; they are two faces of a white savior complex and American passivity.

I don’t believe I would have been able to say all I wanted to say without the aid of characters in this book.

CQ: Let’s talk a little bit about the settings mentioned throughout the book. What is the significance of the setting New London, Connecticut? Early in the book, you write, “I have never been to New London, Connecticut.” In the narrative of the Godfish, cat, and moon, New London is both real and unreal, and the wooden house they live in is centric to “unnatural happenings” and set apart from the “real life giant black road.” And what about the sites of pilgrimage throughout the book? Is America also a site to make a pilgrimage to, or is it a place to escape to?

AR: I have a love for places and the social cultures they inevitably hold. I am someone who has been in constant movement her whole life, and I believe places to be their own characters, to have their spirits. Therefore, the different locations in the book are all real, even the unreal ones. They are their own breathing, living organisms.

And that’s how New London, in Connecticut, feels to me. I have never been. In the book, it is a place of “unnatural happenings” as, just as written in the book, it is a place where Godfish died.

The character who is embodied in Godfish was my high school best friend, A. He went to Connecticut College (in New London, Connecticut) and was hit by a drunk driver while he was crossing the road at night to go to his dorm. The drunk driver, instead of calling for help, pulled A’s body aside and drove away. Leaving him. Right there. To spend a cold December night outside. He was found the next day. His date of death is merely an estimation.

I was myself a sophomore at Bennington College when I received the news. This was December 2015. I was devastated. Over the years of grieving, New London, Connecticut became a significant image for me. The side of the road A was on was very real. I don’t know what it looks like in real life. But in my head, there is a whole image. I live with the happenings of that night every time I am grieving. How can I have such vivid imagery exist when I was not even physically present? That’s the power words have over me.

The moon that captures and cannot fully lift Godfish embodies “moonshine,” intoxication, which failed both Godfish (and A). In the end, my friend was a gold marking on the road. And I believe when I started to write about Q [my friend who passed away after being in a coma], A came forward into the poetry as well. They both took me on the journey of characters and settings, and the book’s narrative reckons with all our losses and its impact.

Is that a sort of pilgrimage? I believe so.

CQ: The book opens with House Mouse climbing and climbing until it gets to the wishing tower. Godfish wishes to be able to swim to the sun, its beloved. The moon wishes to draw Godfish to itself. In Islam, Jannat-ul-Firdous, we learn, is a “place in heaven that is of the highest level, reserved for the most pious, the most special, the most loved.” Do you think the striving for height is a universal human desire? How do height and religion intertwine?

AR: Who are we but an accumulation of our wantings? Humans have inane, uncontrollable, desires that make us get out of the ordinary and strive for something that can give us, even for a single moment, a rich breath of fresh extraordinary. To be human is to be full of wanting, to exist in that kind of inevitable strive. And that kind of striving will always achieve some kind of height.

But my goal through the book, and of course for my own reckoning as a young ambitious Asian immigrant in the American landscape, was to ask what those systems of value ask of us. These “heights” we climb to that are a measure of our worth, giving our human life a value. In order to have value, we keep climbing. But until when?

I was thrown into this disarray because Q and I were ambitious young Asian women from so-called “third world countries” and quite alike in our dispositions. We wanted to be accomplished. To have value as individuals and not be reduced to our Asian womanhoods. But that striving killed us. I watched her fall. And I found myself falling. Like most Asians, we were sold to ideas of hard work leading to value, such as our grades, the length of our CVs, the honors and fellowships and residencies and awards. We were accomplished. But we did not have enough value to win the system that was built against us.

So what did we strive for?

As I was grieving, religion became my literature and God my mentor. I grew up with Islam but as with most religious countries, religion seeped in as a way of life rather than a radicality. Islam is a part of my cultural identity. It is part of my language. Islam is a constant reminder of how to live a life that prepares us for death. And even though I am (and was!) so young, to be handed so many deaths of so many loved ones left me in disarray. I was alone in the American landscape without much support or, as we all have experienced our capitalist systems, empathy. When I finally turned again towards Islam, I was looking for some sense that the West, and Western literature, could not afford me.

I will always say that I am not a religious person. After all, religion is a tool to control the masses. I don’t want Coining A Wishing Tower to be a religious book. I am, however, deeply spiritual. I do have faith in the unknown. I do believe in a God. Maybe when I am brave enough to proclaim it externally, I can even say my God. I have belief in the many rituals that help us decipher the literals of our lives towards a healthy figurative. A true kind of poem. It is inevitable for me to not see God with poetry.

CQ: Many of the prose poems—and the arcs of the House Mouse, the tower, the Godfish, cat, and moon—are written in a parable-like tone. Some of them also verge on fairy tales. You have such wonderful lines and imagination when, for example, House Mouse is cooking in the tower:

“House Mouse cooked fish for the first meal, corn for the

second meal, and melted cheese for the third meal. The

tower is one room full of great imaginings working towards

not staying imagined…”

Or when the moon tries to bring Godfish to itself:

“With every mustered strength, the moon lifts the water, rounds

Godfish into a dripping ball and pulls it through the opened

window only to bring it to a float and a hover in the storming

snow of New London, Connecticut….”

What was the influence of parable and fairy tale in your writing of these poems? Do you consider these narratives allegories?

AR: I celebrate poetry because a good functioning poem has great intentionality. If you spend enough time even with a single line, you can see how the poet has chosen to lay the words next to each other the way they are. Nothing is random. And everything adds to something else.

I do a lot of work with symbolism and imagery, often lent from my own life. I am always in awe at the contrast and the magic I see in front of me. For example, I am currently in Paris, sitting in a gorgeous reading room at Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Public Library of France) answering these questions, where I find myself watching a parade of silent children running through the rows of hunched working adults. They are not laughing. Or making any kind of noise. They are just running through the gorgeous rows of tables. What a contrast! What image and magic! And hardly anyone is looking up! Doesn’t that feel like a fairy tale? Or an allegory? Children running through a grand beautiful reading room of a world-famous library full of frowning adults?

I do the same in the verses you have pointed out. When I put [these contrasts] of the imagined and unimagined together, I surprise myself.

CW: Do you believe in epiphany? How does epiphany play a role in these poems?

AR: I believe in wonder, which can be quite like epiphany, but is not always the same. Epiphany feels like a lightbulb moment of occasional discovery, but wonder feels like a series of discoveries that were always present but are now fully being seen.

In this way, the form of the book holds a kind of wonder. It is an epic told in fragments. Even though I wrote it linearly and the editorial process did not include rearrangements but just clarifications, I saw how one narrative thread began to breathe while still supporting the other threads.

When I read the book out loud in readings, I flip through the book at random and read pieces from it. I am faced with more wonder in this as well.

CQ: Google is also frequently cited throughout the poems. Often, Google’s word is taken as factual and fills in missing gaps in the speaker’s knowledge—e.g. Google speaks on the status of New London, Connecticut, as a small city; on how many lives cats have; on what Islamic Barzakh is. Why did you invoke Google and what is the role of human technology in understanding these characters and poems?

AR: Isn’t Google some form of god now? We rely on it for all our small and big questions and immediately believe what it tells us. “Google says…” instead of “God says.” I find in both these common phrases a kind of significant mimicry.

In a past that’s not too far off (I am thinking of my parents’ lives), information was not accessible at all. My parents were probably faced with so much unknown but still had to strive forward with whatever understanding and skills they did have. They couldn’t just Google how to exactly use a new microwave they bought or how to apply for a visa to travel. In these observations, Google has become such a huge part of our contemporary lives that without it, we wouldn’t often know what to do. And with it, we often are also told how to live a life and exactly what to do.

Maybe I wanted to have Google in the book because so much of our consolations and salvation hinges on asking. In the past, we sat in prayer and asked. And now we get on our phones, maybe our hands poised ritually the same, and ask. We get answered in both ways. We believe. And sometimes, we don’t.

CQ: Another theme that pops up in the latter half of the book is forgetting. Of the Islamic heaven, you write, “Any kind of remembrance of our past lives, any regret, every love, it will all be flushed.” You, the speaker, ask if you will be forgotten on the day of judgment, and the mother says, “It’s inevitable…you will forget me too.” When the cat finds Godfish, dead, you write, “Would death tear them apart to a degree of absolute forget?” These lines really tugged at my heart. The fear of forgetting my loved ones after death is terrifying . How are these poems a response to the question of whether death is the ultimate forgetting?

AR: What we don’t remember also brings us relief. That’s the concept most Muslims have about death and afterlife. If I don’t remember the extent of love I feel for my mother, I would not feel the extent of her loss. I would be relieved of grief and the pain of it.

This is scary. But also, to some degree, comforting. There is consolation in thinking we won’t always be yearning for the ones we lose.

I have tried to tackle the question of love and endings through the poems in small and big ways. The last prose block of House Mouse “returning” holds that life and death can exist in mimicry. But what bridges each ending with another beginning is change and transformation.

CQ: There are a series of transformations: Godfish into a fish, the wishing tower into a pile of rubble. Are these “failed” transformations? Are they an inevitable part of the cycle of life?

AR: I don’t believe in “failed” transformations, and I think maybe that was what I was trying to truly say throughout this epic. Even though Godfish loses its God-ness, its existence still transformed the moon and the cat. The wishing tower is no longer able to grant wishes, and then it loses its life. But it transforms into something else, even if that is rubble which will erode away.

These losses are, in some ways, an indication of life’s inevitable end, yes, but [writing this book] also gave me the gift [of knowing] that there will always be some kind of other journey. Any end we think of is a ripple effect towards something else, beyond comprehension.

These fragmented thoughts are captured in the fragmented poems. We can see the “afterlives” of House Mouse, the Godfish and the tower. [I wanted to show how] there is never any true failure in our conventional ideas of failing. Things that “fall” fall to somewhere else.

CQ: Do you consider these poems of loss?

AR: Absolutely. But not only. These poems are full of grief. But also consolation. Also philosophical nurturings. They are an encouragement to move away from our unconventional thinking of the most universal experience of loss itself.

CQ: At the end of the book, House Mouse is somehow resurrected. I loved this ending, which felt joyous, miraculous, and yet also sad and full of grief because there is no one around to meet House Mouse. What are we to make of House Mouse’s return to life? What is House Mouse returning to?

AR: House Mouse holds huge parts of me as well as huge parts of the speaker, which, of course as poets say lingo, is both me and not me. The speaker leaves home, Pakistan, and goes to America, fulfilling her teenage dream to leave, but the speaker also returns. And with every return, there is change. Decay. Death. Loss. Transformations.

And each immigrant really asks these questions if they return [to where they have left]: “What am I returning to?” “What makes life life here and how much of it I have left?” “Who waits for me and who could not?”

“What has died and what still lives?”

Returning is hard. It is full of lamenting and an inconsolable feeling. We have to reckon with the relativity of time, the loss of romance, and changes that override our initial memories. House Mouse finally returns to the home which it left in the first prose block of the book. But so much has changed. What is home now?

I think there is consolation and love in the fact that we have our return. Even if our parents die. Even if our houses change. Even if the furniture gets full of dust. Just because there is this kind of loss, does not mean we do not feel all the presence of what home is there. Maybe, in life, forgetting can relieve us of pain, but remembrance reminds us of the original love we were given, however much it has been transformed.

CQ: You published Coining a Wishing Tower during the lockdown. Where were you, location-wise, when you heard that your book was accepted for publication? How did COVID-19 affect your experience writing and publishing this chapbook?

AR: This is actually a funny story. The day I got the email that I won the Broken River Prize from Platypus for the book was also the day Biden won (or, well, Trump lost) the elections—November 7 2020. We were all under strict Covid lockdown, but because of the election results, the streets of Brooklyn were flooded with cheers and shouts and music. We all ran through the streets. In that way, I felt I was also celebrating my own little win of accomplishing a dream (the wish I had coined a long time ago). The book was mostly written in 2019 around the loss of Q. But this book definitely was a huge victim of the pandemic aftermath. What with delays in publishing and then my press’s bankruptcy, my book only had a life in this world for one year. But I believe in its return. The life after its life.

CQ: What’s next for you?

AR: Even though I often fail to keep it as simple as the words I am about to say, all I truly desire is to keep writing. I am deeply in love with poetry. And I don’t think this affair will end at all. I am hoping to keep at it and, in small and big ways, keep being read.

To more poems! To more books!

Ayesha Raees عائشہ رئیس identifies herself as a hybrid creating hybrid poetry through hybrid forms. Her work strongly revolves around issues of race and identity, G/god and displacement, and mental illness while possessing a strong agency for accessibility, community, and change. Raees currently serves as an Assistant Poetry Editor at AAWW’s The Margins and has received fellowships from Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Brooklyn Poets, and Kundiman. Her debut chapbook “Coining A Wishing Tower” won the Broken River Prize, judged by Kaveh Akbar, and is published by Platypus Press. From Lahore, Pakistan, she currently shifts around Lahore, New York City, and Miami.

INTERVIEW WITH MÓNICA GOMERY

Mónica Gomery is a rabbi and a poet based in Philadelphia. Chosen for the 2021 Prairie Schooner Raz-Shumaker Book Prize in Poetry, judged by Kwame Dawes, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, and Hilda Raz, her second collection, Might Kindred (University of Nebraska Press, 2022) skillfully interrogates God, queer storytelling, ancestral influences, and more.

FWR: Would you tell us about the book’s journey from the time it won the Prairie Schooner Raz-Shumaker Book Prize to when it was published? In what ways did the manuscript change?

MG: The manuscript didn’t change too much from submission to publication, though it changed a lot as I worked on it in the years prior to submitting it. Kwame Dawes is a very caring editor, and he really gave the poems space to breathe. His edits largely came in the form of questions. They were more about testing to see if I had thought through all of my decisions, guiding me toward consistency. The copy editing at the end was surprisingly tough. I realized how sculptural poetry is for me, how obsessive I am about the shape of poems on the page, and the visual elements of punctuation and lineation. I spent hours making decisions about individual commas – putting them in, taking them out, putting them back in… This was where I felt the finality of the book as an object. I experience a poem almost as a geological phenomenon, a shifting ground that responds to tectonic movement beneath it, a live landscape that moves between liquid and solid. Finalizing the details of these poems meant freezing them into form, and it was hard to let go of their otherwise perpetual malleability.

The last poem to enter the book came really late. I wrote “Because It Is Elul” in the summer of 2021. Right at the last possible moment, I sent Kwame two or three new poems that I was excited about and asked if he thought I could add them. He told me to pick one new poem and add it to the book, and otherwise, to take it easy – that these new poems were for the next collection, and to believe that there would be a next collection. That was a moment of deeply skilled mentorship; his ability to transmit a trust and assurance that this wouldn’t be the end, that we’re always writing toward the next project, the next iteration of who we’re becoming as artists. It meant a lot to hear this from such an incredible and prolific writer. It settled me and helped me feel the book could be complete.

FWR: When did you first start submitting Might Kindred to publishers and contests? I would love to hear about your relationship with rejection and any strategies you may have for navigating it in your writing life.

MG: I started writing the poems in Might Kindred in 2017 and began submitting the manuscript as a whole in 2021. I’m a slow drafter, and it’ll take me years to complete a poem. So too for a manuscript – the process feels extremely messy while I’m in it, but I’ve learned that what’s needed is time, and the willingness to go back to the work and try again. With my first round of rejections, I wondered if I’d compost the entire manuscript and turn to something to new, or if I’d go back in and refine it again. The rejections rolled in, but along with them came just enough encouragement to keep me going – kind reflections from editors, being a finalist multiple times – and then Kwame Dawes called to tell me Might Kindred was accepted by Prairie Schooner for the Raz/Shumaker Prize.

On my better days, I think rejection is not just an inevitable part of the creative process, but a necessary one. Which isn’t to say that I always handle rejection with equanimity. But it has a way of pulling me back to the work with new precision. It generates a desire in me to keep listening to the poem, to learn more about the poem. In some ways, this is the only thing that makes me feel I can submit in the first place – the knowledge that if a poem isn’t quite ready, it’ll come through in the process. It’ll boomerang back for another round of revision. Rejection removes the pressure to be certain that a poem is done.

Jay Deshpande once told me that every morning, a poet wakes up and asks themselves: Am I real? Is what I’m doing real? And that no matter the poet’s accomplishments, the charge behind the question doesn’t change. So, we have to cultivate a relationship to our practice as writers that’s outside of external sources of permission or validation. Jay offered that the poet’s life is a slow, gradual commitment to building relationships with readers – which I understood as an invitation to pace myself and remember to see the long arc of a writing life, as opposed to any singular moment in time that defines one’s “success” as a writer. I try to remember this when I come up against my own urgency to be recognized, or my tenderness around rejection. I want to write for the long haul, so, I have to try and value each small bright moment along the way. Every time I find out that someone who I don’t already know has read one of my poems, my mind is completely blown. Those are the moments when poetry is doing its thing– building community between strangers, reaching across space and time to connect us. And I think that’s what makes us real as poets.

FWR: In “Immigrant Elegy for Avila,” you refer to mountain as a language. You return to the imagery in “God Queers The Mountain”. Would you talk a little about how the mountain came to be a part of your creative life?

MG: Some of it is memory work. As a child, my relationship to Venezuela, when I reach for it in my mind’s eye, had to do with feeling very small in the presence of things that were very large– driving through the valley of El Ávila to get to my grandparents’ houses, swimming in enormous oceans. Since this book reaches back toward those childhood memories, and wonders about being a person from multiple homelands, the mountain started showing up as a recurring presence. The mountain was a teacher, imparting certain truths to me by speaking to me “in a mountain language” that I received, but couldn’t fully translate. This is what it feels like, to me, to be a child of immigrants–– all this transmission of untranslatable material.

Some of it is also collective memory, or mythic memory work. The mountain in “God Queers the Mountain” is Sinai, where the Jewish people received Torah and our covenant with God. That poem seeks to reclaim Mt. Sinai as a site of queer divinity and queer revelation. Similarly, this feels like an experienced truth that’s not easily rendered into English.

On the cover of Might Kindred is a painting by Rithika Merchant, depicting a person’s silhouette with a natural scene inside of them. The scene crests on a hilltop and overlooks the peak of a mountain, painted right there at the heart of the mind. The mountain in the painting is against a thick night sky, full of constellations and a red harvest moon. I can’t tell you how true this painting feels to me. Going back to Mt Sinai for a moment, in Torah it’s the meeting point between earth and heaven, where the divine-human encounter happens. It’s a liminal, transitional space, where each realm can touch the other, and it’s where the people receive their relationship to the divine through language, mediated by text. I love the claim, made by Merchant’s painting, that this meeting point between earth and sky, human and heavenly, however we want to think about, lives within each of our bodies. The possibility of earth touching heaven, and heaven touching earth, these are longings that appear in the collection, played out through language, played out at the peak of the mountain.

FWR: I love that “Prologue” is the eighth poem in the collection. Some poets may have chosen to open the collection with this poem, grounding the reader’s experience with this imagery. What drove your choice of placement? How do you generally go about ordering your poems?

MG: You’re the first person to ask me this, Urvashi, and I always wondered if someone would! Ordering a collection both plagues and delights me. I’m doing it again now, trying to put new poems into an early phase of a manuscript. Lately I’m struggling because every poem feels like it should be the first poem, and the placement of a poem can itself be a volta, moving the book in a new direction. The first handful of poems, maybe the first section, are like a seed– all the charged potential of the book distilled and packed tightly within those opening pages, waiting to be watered and sunned, to bloom and unfold. There’s a lot of world-building that happens at the beginning of a poetry collection, and one of the rules in the world of Might Kindred is the non-linearity of time. By making “Prologue” the eighth poem, I was hoping to set some rules for how time works in the book, and to acknowledge the way a book, like a person, begins again and again.

At one point, I had Might Kindred very neatly divided by subject: a section on Venezuela, a section on Queerness, a section rooted in American cities, a section about my body, etc. I shared it with my friend Sasha Warner-Berry, whose brilliance always makes my books better. She told me, “The poems are good, but the ordering is terrible.” Bless her! I really needed that. Then she said, “You think you need to find subject-based throughlines between your poems, to justify the collection, but the throughline is you. Trust the reader to feel and understand that.” It was a mic drop. I went back to the drawing board, and ordering became an intuitive process: sound-based, sense-based, like composing a musical playlist.

I want to think about the space a reader inhabits at the end of each poem. I want to feel and listen into that silence, tension, or question, and then respond to it, expand upon it, or juxtapose it, with what comes next. I also used some concrete tools. I printed each poem out as a half-pager, so that it was tiny and easy to move around on a floor or wall. I marked and color-coded each poem with core motifs, images, and recurring themes. This helped me pull poems together that spoke to one another, and also to spread out and braid the themes. Similarly, I printed out a table of contents, and annotated it, to have that experience of categorizing poems from a birds-eye-view.

FWR: There are four poems, scattered throughout the book, titled “When My Sister Visits”. These short poems are some of the most elusive and haunting poems in the text. Would you tell us about the journey of writing these linked poems?

MG: These poems began after a visit I’d had with my friend and mentor, Aurora Levins-Morales. I hadn’t seen her in a long time, and I was living in Chicago, where I didn’t have a lot of close people around me. Aurora came to town, and we did what we always do– sit and talk. On this visit, she also showed me around her childhood neighborhood in Chicago, including the house she’d lived in as a teenager, and the streets she’d walked as a young feminist, activist, and poet. It was a very nourishing visit, and afterward when I sat down to write, the first words that came to me were, “When my sister visits…” This was interesting because Aurora isn’t my sister. She’s my elder, teacher, and friend, so I knew something about the word sister was working in a different way for me, almost as a verb. What does it mean to be sistered by someone or something? This question came up recently in a reading I did with Raena Shirali. Beforehand, we both noticed the recurring presence of sisters in one another’s books, and we deliciously confessed to each other over a pre-reading drink that neither one of us has a biological sister. The word sister has a charge to it, I think especially for women.

At first, I wrote one long poem, excavating the presence of a shadow sister in my life who appears to accompany me and reflect parts of myself back to me, especially parts of me that I think shouldn’t be seen or given voice to. This sister embodies my contradictions, she asks hard questions. I was drawn to writing about her, somehow through that visit with Aurora, in which I felt that I belonged with someone, but that the belonging was fraught, or pointed me back to my own fraughtness.

This poem was published in Ninth Letter in the winter of 2020, under the title “Visit,” and I thought it was finished! Later, I worked with Shira Erlichman on revising the poems that became Might Kindred. Shira invited me to return to seemingly completed poems and crack them open in new ways. Shira’s amazing at encouraging writers to stay surprised. It’s very humbling and generative to work with her. So, I chopped the original sister poem up into smaller poems and kept writing new ones… Shira advised me to write fifty! This gave me the freedom to approach them as vignettes, which feels truer to my experience of this sister in my life– she comes and goes, shows up when she wants to. She’s a border-crosser and a traverser of continents, she speaks in enigma and gets under my skin, into my clothes and hair. Bringing her into the book as a character felt more accurate when this poem became a series of smaller poems, each one almost a puzzle or a riddle.

FWR: Ancestors, especially grandmothers, have a powerful presence in these poems. What did you discover in the course of writing these poems? What made you return to these characters over and over?

MG: In Hebrew, the words av and em mean father and mother, and also originator, ancestor, author, teacher. The word for “relation” is a constellation of relationships, which expands the way we might think about our origins. This helps me find an inherent queerness at work in the language of family– how many different ways we may be ancestored by others. And at the core of their etymology, both words mean to embrace, to press, to join. I love this image of what an ancestor is: one who embraces us, envelopes or surrounds us, those whose presences are pressed up against us. We are composite selves, and I think I’m often reaching for the trace of those pressed up against me in my writing.

Might Kindred is driven by a longing for connection. Because the book is an exploration of belonging, and the complexity of belonging in my own life, ancestors play a vital role. There are ancestral relationships in the book that help the speaker anchor into who she is and who and what she belongs to, and there are ancestral relationships in the book that are sites of silence, uncertainty, and mystery, which unmoor and complicate the possibility to belong.

Also, belonging is a shifting terrain. I wrote Might Kindred while my grandmother was turning 98, 99, then 100, then 101. In those years, I was coming to accept that I would eventually have to grieve her. I think there was an anticipatory grieving I started to do through the poems in this book. My grandmother was the last of her generation in my family, she was the keeper of memories and languages, the bridge from continent to continent, the many homes we’ve migrated between. Writing the book was a way of saying goodbye to her and to the worlds she held open for me. There are many things I say in the pages of Might Kindred, addressed to my grandmother, that I couldn’t say to her in life. I wasn’t able to come out to her while she was alive, and in some ways the book is my love letter to her. The queerness, the devotion, the longing for integration, the scenes from her past, our shared past, the way it’s all woven together… maybe it’s a way of saying: I am of you, and the obstacles the world put between us don’t get the final word.

Lastly, I’ll just say, there are so many ways to write toward our ancestors. For me, there’s a tenderness, a reverence, and an intimacy that some of these poems take on, but there’s also tension and resistance. Some of the poems in the book are grappling with the legacies of assimilation to whiteness that have shaped my family across multiple journeys of immigration – from Eastern Europe to Latin America, from Latin America to the US. I harbor anger, shame, heartbreak, disappointment, confusion, and curiosity about these legacies, and poetry has been a place where I can make inquiries into that whole cocktail, where I can ask my ancestors questions, talk back to them, assert my hopes for a different future.

FWR: Three of your newer poems appear in Issue 25 of Four Way Review and I am intrigued by the ways in which there’s been this palpable evolution since Might Kindred. Is that how you see it too, that you’re writing from a slightly different place, in a slightly altered register?

MG: Yes, I do think there’s a shift in register, though I’d love to hear more about it from your perspective! I know something of what’s going on with my new writing, but I’m also too telescoped into it to really see what’s really happening.

I can definitely feel that the first poem, “Consider the Womb,” is in a different register. It’s less narrative, equally personal but differently positioned, it’s exploring the way a poem can make an argument, which has a more formal tone, and is newer terrain for me. It uses borrowed texts, research and quotations as a lens or screen through which to ask questions. I’m interested in weaving my influences onto the page more transparently as I write new poems. This poem is also more dreamlike, born from the surreal. It’s holding questions about the body, generativity, gender roles and tradition, blood, birth and death, the choice to parent or not. I think the poem is trying to balance vulnerability with distance, the deeply personal with the slightly detached. Something about that balance is allowing me to explore these topics right now.

The other two poems take on major life milestones: grieving a loss and getting married. I’m thinking of some notes I have from a workshop taught by Ilya Kaminsky – “the role of poetry is to name things as if for the first time.” Loss and marriage… people have been writing poems about them for thousands of years! But metabolizing these experiences through poetry gives me the chance to render them new, to push the language through my own strange, personal, subjective funnel. Kaminsky again: “The project of empire is the normative. The project of poetry is the non- normative.” There are so many normative ways to tell these stories. Ways to think about marriage and death that do nothing to push against empire. I think my intention with these two poems was not to take language for granted as I put them onto the page.

FWR: Is there a writing prompt or exercise that you find yourself returning to? What is a prompt you would offer to other poets?

MG: I once learned from listening to David Naimon’s podcast Between the Covers about a writing exercise Brandon Shimoda leads when teaching, and it’s stayed with me as a favorite prompt. He would have his class generate 30 to 50 questions they wanted to ask their ancestors, and go around sharing them aloud, one question at a time, “Until it felt like the table was spinning, buoyed by the energy of each question, and the accumulation of all the questions.”

As you pointed out, writing with, toward, and even through, my ancestors, is a theme of Might Kindred, and I think it’s one of the alchemical transformations of time and space that poetry makes possible. I love Shimoda’s process of listing questions to ancestors, which feels both like a writing exercise and a ritual. It draws out the writer’s individual voice, and also conjures the presence of other voices in the room.

I’ve used this exercise when teaching, credited to Shimoda, and have added a second round– which I don’t know if he’d endorse, so I want to be clear that it’s my addition to his process– which is to go around again, students generating a second list of questions, in response to, “What questions do your ancestors have for you?” I’m interested in both speaking to our ancestors and hearing them speak to us, especially mediated through questions, which can so beautifully account for those unfillable gaps we encounter when we try to communicate with the dead.

In Might Kindred, there’s a poem called “Letter to Myself from My Great Grandmother” that was born from this kind of process. It’s in my ancestor’s voice, and she’s asking questions to me, her descendent. My book shared a pub day with Franny Choi’s The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On, which I think is an astonishing collection. In it, she has a poem called “Dispatches from a Future Great-Great-Granddaughter.” In the poem she’s made herself the ancestor, and she’s receiving a letter, not from the past but from the future, questions addressed to her by her future descendent. I’m in awe of this poem. She models how ancestor writing can engage both the future and the past, and locate us in different positions– as descendent, ancestor, as source or recipient of questions. The poem contains so many powerful renderings and observations of the world we live in now– systems, patterns, failings, attempts. She could have articulated all of these in a poem speaking from the present moment, in her own present voice. But by positioning her writing voice in the future, she creates new possibilities, and as a reader, I’m able to reflect on the present moment differently. I feel new of kinds of clarity, compassion, and heartbreak, reading toward myself from the future.

These are the questions I return to, that I’d offer other writers: Think of an ancestor. What’s one question you have for them? What’s one question they have for you? Start listing, and keep going until you hit fifteen, thirty, or fifty. Once you have a list, circle one question, and let it be the starting point for a poem. Or, grab five, then fill in two lines of new text between each one. Just write with your questions in whatever way you feel called to.

FWR: Who are some of your artistic influences at the moment? In what ways are they shaping your creative thoughts and energy?

MG: Right now, I’m feeling nourished by writers who explore the porous borders between faith and poetry, and whose spiritual or religious traditions are woven through their writing in content and form. Edmond Jabés is a beacon, for the way he gave himself permission to play with ancient texts, to reconstruct them and drop new voices into old forms – his Book of Questions is one I return to again and again. I love how he almost sneaks his way back into the Jewish canon, as though his poems were pseudepigraphic, as though he’s claiming his 20th century imagined rabbis are actually excavated from somewhere around the second or third centuries of Jewish antiquity. I’ll never stop learning from his work.

Other writers along these lines who are inspiring me right now include Leila Chatti, Alicia Ostriker, Alicia Jo Rabins, Dujie Tahat, Eve Grubin, and Mohja Khaf. Kaveh Akbar, both for his own poems and for his editorial work on The Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse. Joy Ladin, whose writing is a guidelight for me. Rilke, for his relentless attempts to seek the unlanguageable divine with the instrument of language. I’m trying to write on the continuum between ancient inherited texts and contemporary poetry. These writers seem to live and create along that continuum.

I’m also reading Leora Fridman’s new collection of essays, Static Palace, and Raena Shirali’s new book of poems, Summonings. Both books merge the lyrical with the rigor of research; both are books that return me to questions of precision, transparency, and a politicized interrogation of the self through writing. On a different note, I’m thinking a lot these days about how to open up “mothering,” as a verb, to the multitude of ways one might caretake, tend, create, and teach in the world. As I do that, I return to the poems of Ada Limón, Marie Howe, and Ama Codjoe. And lastly, I’m trading work-in-progress with my friends and writing siblings. On a good day, it’s their language echoing around in my head. Right now, this includes Rage Hezekiah, Sally Badawi, emet ezell, and Tessa Micaela, among others. This is the biggest gift – the language of my beloveds doing its work on me.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview, Monthly, Poetry

VERDIGRIS by Mariana Sabino

Four years had passed since I returned to this building, the old city, and the old job. At work digitizing the poster of another Czech New Wave film—this one depicting algae sprouting from a woman’s head, dark eyes sparkling with silver pin lights that reminded me of plankton—my heart started racing so fast I handed over my shift and went home. I sensed another panic attack. What did it was the smell of jasmine that wafted through that image—impossible but as real as a bite.

The jasmine had been trailing me. At first it was like a furtive glance across the room. The scent of a blooming vine would slither into the apartment with a passing breeze from an open window or suddenly shut door. It even made its way in the stillest of air that had been chewed on for days, keeping out the gelid winter. I checked my clothes, my linen, perfume bottles, but that couldn’t be it. I didn’t wear perfume, the bottles were decorative, my grandmother’s mementos. In the summer and fall I’d dismissed the scent as a whiff of viburnum or linden. Jasmine just wasn’t something you would find in Prague. I knew that smell; I knew it well.

“Maybe you should go to the hospital,” my co-worker Marketa suggested one day, her eyes scanning me as she held up my coat.

“It’ll pass,” I said.

I measured my steps to the Staroměstská metro station, the snow sludgy and clinging to my hems, wishing I hadn’t worn high-heeled boots. I gripped the rubbery escalator handrail on that interminable descent from which I could hear the train’s distant hum in the earth’s bowels. That whistling, the pounding of wheels, turned into a chugging roar as vertigo washed over me.

Inside my studio, Grandma was listening to a Hana Hegerová record, sitting on the couch and knitting another bright-colored scarf, presumably for me. “You’re early,” she said, watching as I unzipped my boots and put on the slippers by the door.

“Yes,” I said. I was used to finding her in my apartment, especially since she lived upstairs and my studio was officially hers. Her plump, stockinged legs and muumuu-adorned presence were as ubiquitous as the heavy walnut furniture. “I need to lie down,” I said.

Her eyes searched mine as she put the yarn in her canvas bag, slung it over her shoulder, leaned forward and rose with great effort. Lying down on the couch that doubled as a bed, I could feel her warmth on the woolen cushions as I closed my eyes.

“Rest,” she said. “Come over later. I made goulash.”

“I’ll call you if I’m coming over.”

“No need to. Just come in. You need to eat,” she said. I could hear shuffling around the room, the clinking and rinsing of glass in the sink, the creak of the cabinet door as she opened and closed it. How did I end up here again? I saw myself at 5,17, then 29, 50, 72, my entire life spent between this studio and the larger one upstairs, which was my parents’ until they moved to their country cottage and I returned from Brazil.

“You’re lucky they took you back,” Grandma said often enough about my job at the National Film Archives, since I had returned with nothing aside from a suitcase and a few wrinkles. For her, my relationship with Samuel and all those years abroad, they didn’t really count. And for a while I, too, was almost convinced everything had been a long holiday, a mindscape in which life intensifies, attuned to another frequency.

In my early twenties, when I got into film school, I took up Romance languages in my spare time, learning some Italian and then Spanish, but it was Portuguese that intrigued me enough to go to Portugal and then, finally, to Brazil. I’d always been drawn by unknown places and people presented to me through photographs, films, and documentaries. At home, I felt part of the furniture.

After dozing for a couple hours, I put on my jacket and went upstairs. We ate Grandma’s goulash with the television on mute.

“Backgammon?” she asked after dinner.

“Not tonight,” I said, sniffing something. There it was again, the faint smell of jasmine. “Do you smell it?”

She turned on the TV and looked at me impassively. “You’re right. Too many caraway seeds.”

“Not that. The goulash is fine.” With legs propped on the coffee table, her swollen shins caught my attention. “How about a massage?” I asked.

Her eyes lit up, youthful with expectation. Sitting across from her, I picked up her leg and rubbed the pressure points on her feet. Closing her eyes, she basked in pleasure like her big red tabby. In moments like these, I could see the young woman she had been.

“You’re a jewel,” she said, her voice lilting. “Pavel’s a bachelor, you know. Still single, like you.” Worse than unattractive, Pavel had a bland handsome face, a smug grin, and a ready string of infantile jokes that appealed to my grandma.

Re-shifting my weight, I reminded her again: “I have been married.”

“Oh. A beach ceremony in the middle of nowhere doesn’t count,” she said. “Besides, no one knows about it.”

“I know about it,” I said, laying down the peeling, reddened foot.

Snapping her eyes open, she huffed. “That’s it? You’re a tease,” she said.

I got up to wash my hands. By the time I left the bathroom, she was already talking to her friend Helča on the phone. The two compared notes on talent shows—this one called Dazzling Incarnations—while watching. “That’s what passes for talent nowadays,” Grandma usually said, only this time the talent in question happened to pass her test. “She’s the spitting image of Edith Piaf,” she declared. Pressing the cellphone to her chest the way she would’ve done with an old receiver, she looked up at me. “Rest, Evička. Good night.”

As I lay in bed, I watched the snow against the windowpane. The wisps conjured memories. At this time of year, summer in the southern hemisphere would still be in full swing, the sea calm enough to swim at all hours, with tourists alternately reveling and devouring the village like insatiable hounds. Samuel’s three bakeries around town would be so bustling he’d employ additional people, making regular trips to Rio to restock any gourmet merchandise. Jaunty açaí stands would’ve sprouted for the season, and a mixture of techno, international and Brazilian pop, jazz, bossa nova, favela funk would all compete for attention, heard from stand to stand and house to house. Soon, those tourists would be gone, leaving the village, then the town, flushed out with the remains of a summer-long party.