URGENT: NEWS OF THE DEATH OF HIBA ABU NADA by João Melo, trans. G. Holleran

Excuse my urgency, oh right-thinking beings

especially you translucent

and self-referential poets,

but one of our sisters,

the Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada,

has just died in Gaza under the shrapnel of a benevolent bomb,

sent by another God,

different from the one she spoke with

every day.

I hesitated to convey this fateful news

so hastily. Perhaps I should wait

for the leaden grey smoke from the bomb that killed her to dissipate,

while she, surely,

scrutinized the sky for a sliver of light and

maybe even

the last birds.

Or, more convenient yet

it’d be better to say nothing,

until today’s hegemonic oracles,

like all oracles,

circulate an official statement

denying it as usual

without any doubts

or uncomfortable questions.

But when I read

the last words of Hiba Abu Nada before she died,

I was moved to spread this news,

before her banner could be censored

by those who defend selective liberty:

“If we die, know that we are content and steadfast,

and convey on our behalf that we are people of truth!”

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Poetry, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Olivia Elias, trans. Jérémy Victor Robert

Day 21, Words Are Too Poor, October 28, 2023

words are too poor but I have only them

my only wealth

empty my hands & so great the sufferings

here again I press my arms around my chest

here again I get into this old habit of covering the page with little

squares filled with black ink

the little squares of our erasure

/

I write what I see said Etel Adnan* who knew a lot about

mountains’ strength as well as Catastrophe

I also know the power of this Mount facing the sea

Carmel of my very early days Mount Fuji of absence

& denial around which I gravitate above it the

black crows of desolation

as I know all about our Apocalypse which keeps on repeating

repeating the earth turning on its axis the sun that veils its face

/

here’s what I see

the madness of the overarmed Occupying State

crushing bodies & souls live on screens at least until

night falls a night of the end of the world only

pierced by ballistic flashes

in Sabra & Shatila the spotlights

. illuminated the massacre’s scene

today in this Mediterranean Strip of sand

. total darkness shields Horror

the sky explodes in a thousand pieces amongst

monstrous mushrooms of black smoke the time to

count one two three towers collapse one

after the other like bowling pins their inhabitants

inside then get into action the steel monsters

flattening the landscape they call it

(translation: converting this ghetto sealed off on all sides

into a 21st-century Ground Zero)

everyone wondering When will my time come?

& parents writing their children’s name on their small wrists

for identification (just in case)

/

no water no food no fuel & electricity & no medicine

decided the Annexationist Government’s Chief

let’s finish this once & for all & forever they shout

relying on the unconditional support of

their powerful Allies the ones primarily responsible

for our fate by writing it off on the bloody chessboard

of their best interests

as if their contribution to our erasure redeemed their crimes

Hear Ye Hear Ye

proclaims America’s great Chief, waving his veto-rattle

Absolute safety for the Conquerors

Hear Ye Hear Ye

chorus the mighty Allies

/

Gaza / 400 square kilometers/not a single safe place /2.3 million people /half of them children / hungry /thirsty/injured /desperately searching for missing family members dying under the rubble

& Death the big winner

/

they should know that souls cannot

be imprisoned no matter how tight the rope

around the neck & how strong

the acid rains & firestorms

One day, however, one day will come the color of orange/

/a day like a bird on the highest branch**

where we will sit

in the place left empty

in our name

in the great human House

————

*Etel Adnan, “I write what I see,” in Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito: Post-Apollo Press, 1986; Brooklyn: Litmus Press, 2021).

**“One Day, However, One Day,” from Louis Aragon’s homage in Le Fou d’Elsa (1963) to Federico García Lorca, who was murdered, in August 1936, by Franco’s militias.

DAY 74, THERE WILL ALWAYS BE POETS, December 20, 2023

instability a general rule

it seems a new ocean’s on the verge

of emerging in

Africa

& floating between

here

&

there

could affect not only people or land

but also the seasons I experienced it

of fall I didn’t see a single thing

this year the acacia’s

color even changed without

my noticing

one morning looking through

the window I realized

it was there

naked

at its feet a carpet of yellow

leaves littered the ground

nothing to keep it warm

exposed

to the cold icy rain missiles

& here I was & still I am

glued to the screen

startled by every explosion

of the red-little-ball

clinging to the glittering

garlands

as soon as one of the

flesh-eating-red-balls hits

the ground a sheaf of fire

bursts followed

by a huge black smoke

cloud

then

screams

cries

panic

agony

day & night (even

more so at night) keeps on

going the hypnotic

ballet

today

Day 74

74 days of this

will spring come back

or only a long winter

of ignominy cold hunger

history will remember

there will always be poets

to tell the martyrdom

of the Ghetto People

NOTE: An earlier version of this translation appeared on 128 Lit website, December 28, 2023.

HEAR YE, HEAR YE!

At regular intervals shaking his rattle carved with the word veto the Grand Chief of America takes the floor for an urbi et orbi statement

With the utmost firmness

broadcast on a loop

in newspapers on screens

around the world

withwithwithwithwithwithwith

thethethethethethethe

utmostutmostutmostutmostutmost

utmostutmost

FIR/MNESS

like

FER/OCITY

growing

exponentially

utmostutmostutmostutmosT

exceptionallyFirm

FIR/MNESS

FIRE/MESS

Iron balls blazing

in the sky

black & read whirls

it’s raining

black ashes

east bank not west

with the utmost

firmness

We support the Conquerors’

Right to Security

COLIN POWELL. GUERNICA. SCULPTURE

1

The devil is in the detail. Colin Powell–former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of State to the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush, between 2001 and 2005–was said to have placed great importance on this. Unfortunately for him and the legacy he leaves to history, he broke that rule on one memorable occasion

It was on February 5, 2003, when he called for a military crusade against Iraq on the podium of the United Nations, based on false evidence of weapons of mass destruction. His effort resulted in the very thing it was supposed to prevent–the deaths of hundreds/hundreds of thousands of Iraqis–& plunged the country into widespread chaos, which is still unfolding today

That day, UN officials covered with a blue veil a tapestry hanging at the entrance of the Security Council representing Guernica, the monumental work painted by Picasso at the request of the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War. Twenty-seven square meters commemorating the stormy & total destruction of the small town of the same name by the German & Italian air force, on April 26, 1937

2

In March 2021, the tapestry was returned to the Rockefeller family who had loaned it for 35 years & wanted it back. Has it been replaced? With what work? I don’t know, but I’ve got an idea. Let’s offer a cubist sculpture/assemblage of 550 stones extracted from our lands on which Settlers, protected by militias/soldiers & courts, are having a great time

Upon each of these stones

that capture the light so

beautifully

is an inscription: the name of

a village

from yesterday and today

that was

razed/ablaze

May a blue veil cover it when the Guardians of the ghetto & the bantustans take the floor

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

- Published in Poetry, Translation

JUNE MONTHLY: In Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Nearly a year after the October 7 Hamas terrorist attack and Israel’s subsequent escalation of a decades-long project of state-sponsored genocide of the Palestinian people, Gaza continues to face deadly bombings and attacks from Israel. According to Gaza’s Health Ministry, the death toll of Palestinians is in the tens of thousands, with no sign of Israel relenting.

In response to the death and destruction in Palestine, Barricade and Four Way Review joined together to raise the voices of Palestinian poets and others from around the world standing in solidarity with them. While we stand fervently against Anti-Semitism, we also resist its false equation to anti-Zionism; we equally condemn Islamophobia, anti-Arab racism and xenophobia, and imperialism, all of which function together to murder and oppress the poor and working classes and to legitimize expropriation and forced displacement.

The poems you will read here have been previously published in Barricade and represent a desire to use our platforms to uplift and disseminate translations from and in solidarity with Palestinians. Barricade shares contributions on its forum Ramparts, a makeshift oppositional online space founded on the basis of urgency and necessity; Four Way Review has compiled a selection of Ramparts posts here, with the aim of expanding the reach of these writings and giving them a more permanent home.

Four Poems, Olivia Elias (trans. Jérémy Victor Robert)

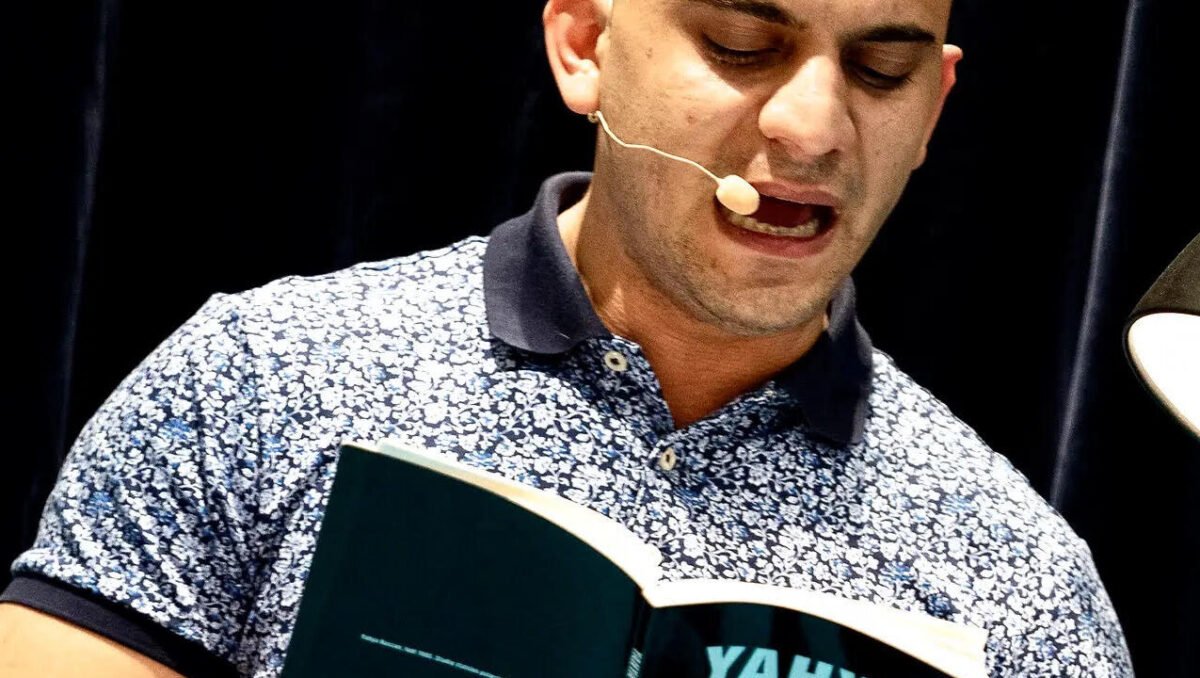

SLUMROYAL, Yahya Hassan (trans. Jordan Barger)

Urgent: News of the Death of Hiba Abu Nada, João Melo (trans. G. Holleran)

- Published in Monthly, Poetry, Translation

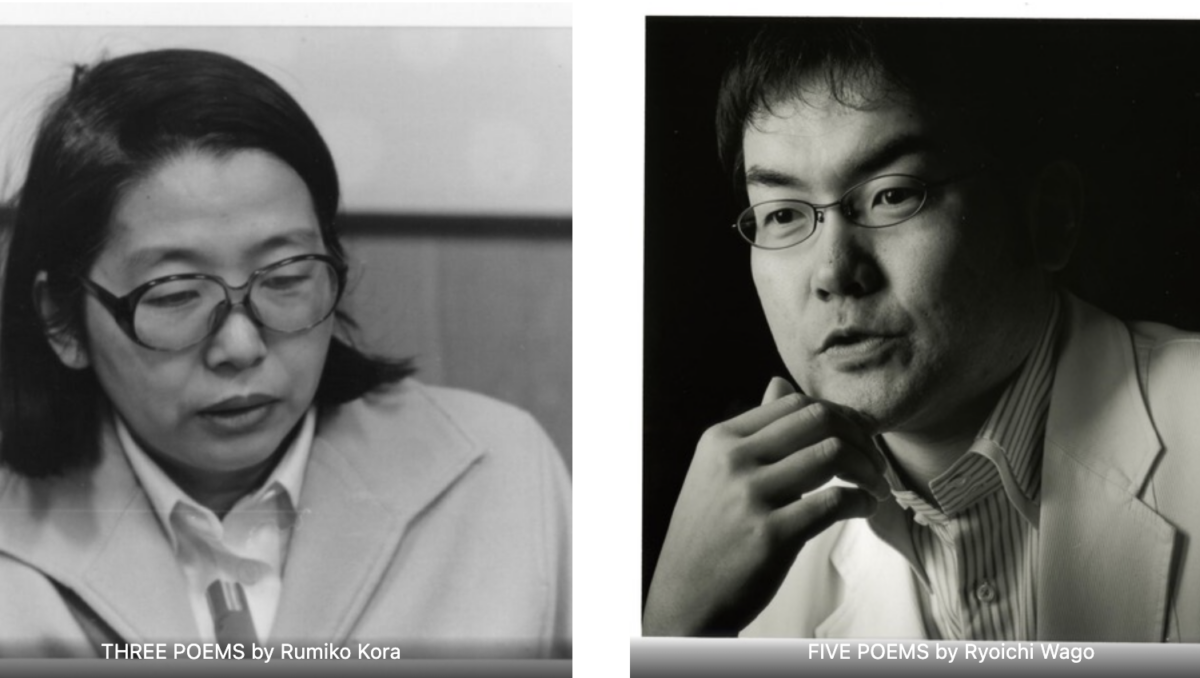

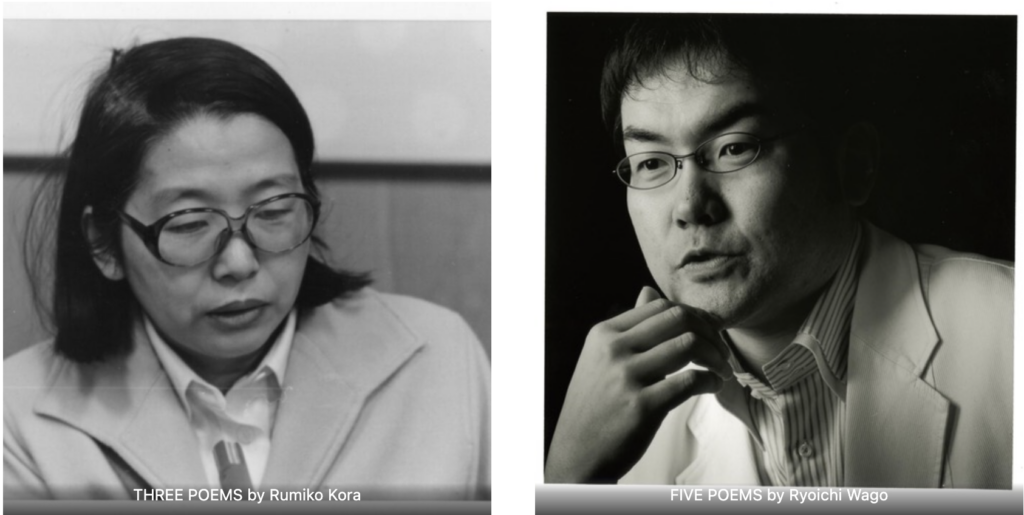

ECOPOETRY FROM JAPAN with Ryoichi Wago and Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FOUR POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

by Judy Halebksy

Ayako Takahashi

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

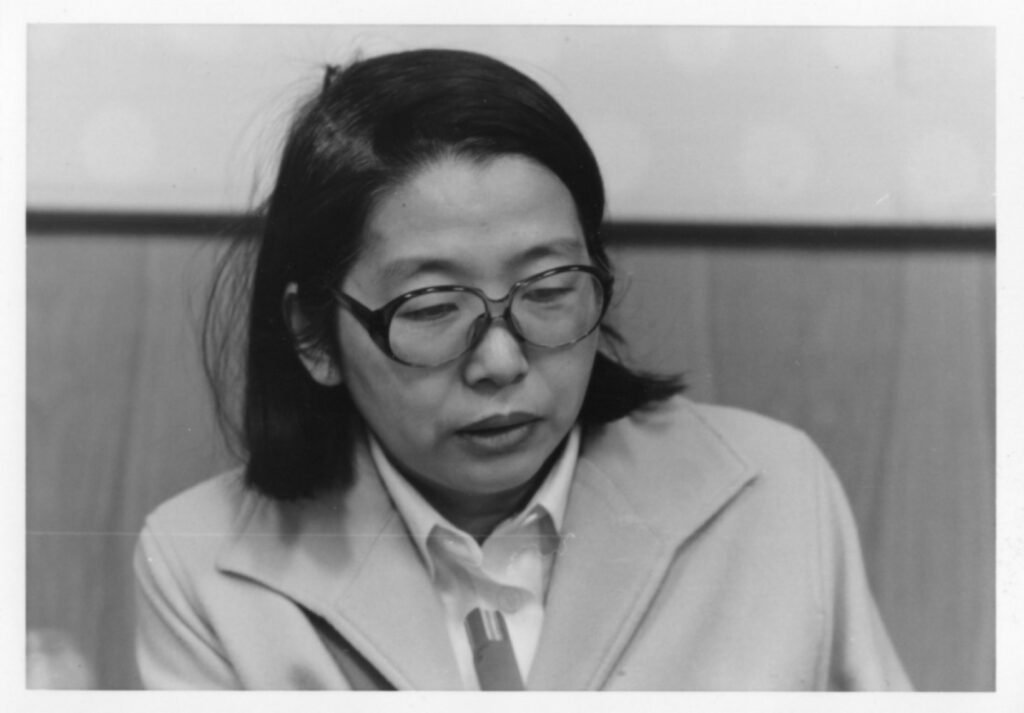

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FIVE POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

This folio shares recent translations from two Japanese poets, Kora Rumiko (1932-2021) and Wago Ryoichi (1968-). Kora’s poems are from the second half and 20th century, and Wago’s were written following the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown that devastated his home region. Writing in different times and from different perspectives, these poets overlap in that their writing draws attention to environmental degradation and inequality while simultaneously voicing a strong sense of place.

Kora was born and raised in Tokyo. Her childhood was shaped by the Second World War and the devastation of the Tokyo fire bombings that she witnessed as a thirteen-year-old. In the changes of the post-war era and the rapid industrialization of the 1970s, her neighborhood grew from a small community to a bustling urban area. Her writing speaks against capitalism and colonialism. At a time when many Japanese writers were influenced by European literary forms, Kora looked toward writers from Asia and Africa, all while drawing inspiration from mythology, envisioning matriarchy, and speaking to the harms and costs of nuclear weapons and nuclear power.

These themes are evident in her poem, A Mother Speaks, which is set within the Noh play A Killing Stone (Sesshôseki). Noh is a somber, serious theatre tradition that has been in living practice for more than six hundred years. Plays often have themes of connecting the dead with the living and of vanquishing evil spirits. A Killing Stone references the legend of the fox spirit and Lady Tamamo’s attempt to use her supernatural power to kill the emperor. As the story goes, her plans fails and her spirit is relegated to a stone that kills any living thing that passes over it. Kora’s poem envisions Tamamo’s power, fertility, and the potential of transformation, offering an embodied, feminist perspective on the Noh play and the legend more broadly.

Wago is a high school teacher and has lived in Fukushima prefecture his whole life. In March 2011, when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear powerplant failed, he did not evacuate, but sheltered in place in his apartment in Fukushima City, 50 miles away from the powerplant. He started a Twitter feed of thoughts and observations, which soon had thousands of followers. Pebbles of Poetry 1, from Macrh 16, 2011, marks the very beginning of his posts and the moment when people were just becoming aware of the radiation leaks. On several occasions, Wago visited areas inside the evacuation zone, a 12-mile radius of the power plant. He wore a protective suit and a radiation monitor. His poem Screening Time was written after one of those visits. Wago’s writing addresses environmental degradation with an ecopoetics that not only explores the human toll of this catastrophe, but also includes the perspectives of cows abandoned in the fields; the fruits and crops left to waste; the once vibrant towns that now stand empty; and the soil, the ocean, and the air.

January 7, 2021, is one of a series of poems that Wago wrote marking ten years since the nuclear meltdown. It voices a more composed perspective on the memories and experiences of his earlier writings. It opens with a description of flying above the evacuation zone and includes a conversation with a dairy farmer forced to evacuate the area and abandon his herd. The poem integrates quotes from Wago’s twitter feed on March 22, 2011 in the first days following the meltdown; contextualizing, in this way, the original posts, integrating them with images and details to create an immersive sense of presence. Much of Wago’s work is dedicated to restoring Fukushima prefecture, not just in terms of environmental restoration, but also of the culture and lifestyle of the region and the well-being of future generations.

Ayako Takahashi and I have translated these poems collaboratively, working together weekly over video chat since 2017. Ayako tends to favor a more literal translation, while I am often most concerned that the translations work as poems. Our hope is that we have landed someplace in the middle, maintaining with fidelity the vitality of the original works.

- Published in Interview, Monthly, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Wago, Ryoichi. Since Fukushima. Trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi. Vagabond Press, 2023. Print.

Purchase the book here.

Screening Time

November 26th, 2011

—exiting the restricted area, a 20 km radius of the power station

screening palms

screening the back of my hands

screening with my hands up

screening with my hands down

screening over my head

screening the back of my head

screening the sole of my left shoe

screening the sole of my right shoe

screening my entire body

screening what is outer space

screening what is a hometown

screening what is life

screening what is radiation

to us

what is most precious

what cannot be measured

You

(no date)

precious

you

what are you

doing now

you are me

I am you

from the obsidian depths of night

it’s you I am thinking about

and for me

from me

you

I won’t give up on

for you

I won’t give up

JANUARY 7th, 2021

I swooned

reeled

reeling.

it was spring, one year after the disaster.

I boarded a helicopter and traveled into the restricted zone,

the 20 km surrounding the nuclear power station,

high above, looking over the land below.

from a perfectly kept beach,

we crossed into the forbidden sky,

as though we were trespassing.

the land left just as it was that day.

huge, concrete wave-breaks strewn on the beach.

houses, cars, and boats hit by the tsunami, scattered everywhere.

mud and stones spread across roads and fields, electric poles keeled over.

dogs chained at front doors and left behind….

time stopped.

no.

time doesn’t exist.

I remembered that.

dizzy. still now.

could be. the aftershocks.

which continue even now, I think.

the other day, I heard a story

from a dairy farmer living within 20 km of the power station.

“the cows were so hungry

there were teeth marks all through the barn and along the fences.

until the end, trying to find something to eat.

they wasted to skin and bones then fell over…”

*

“tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, getting by. an aftershock.

tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, standing here. an aftershock.

a local broadcaster says, now everyone has heard of Fukushima. if we can recover, it’s an opportunity for us, he says. we’re known all over the world. an aftershock.

we clung to hope. tried to be grateful. is there a reward? maybe. but.

our families and our roots are here. famous around the world? I’ll burn the map.

an aftershock.

it’s calm. the night air, radiation. an aftershock.”

(March 22, 2011)

PEBBLES OF POETRY

Part 1: March 16th, 2011, 4:23 am —March 17th, 2011, 12:24 am

Such a huge catastrophe. I was staying at an evacuation center but I’ve now pulled myself together and returned home to work. Thank you for worrying about me and encouraging me, everyone.

March 16th, 2011. 4:23 a.m.

Today, it is six days since the earthquake. My way of thinking has completely changed.

March 16th, 2011. 4:29 a.m.

I finally got to a place where all I could do was cry. My plan now is to write poetry in a wild frenzy.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

Radiation is falling. It is a quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

This catastrophe is so painful, and for what?

March 16th, 2011. 4:31 a.m.

Whatever meaning we can find in all this might come out in the aftermath. If so, what is the meaning of aftermath? Does this mean anything at all?

March 16th, 2011. 4:33 a.m.

What does this catastrophe want to teach us? If there’s nothing to learn from this, what should I believe in?

March 16th, 2011. 4:34 a.m.

Radiation is falling. A quiet quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:35 a.m.

I was taught, “wash your hands before coming in the house.” But there isn’t any water for us to use.

March 16th, 2011. 4:37 a.m.

Relief supplies haven’t arrived in Minamisôma. I’ve heard that the delivery people don’t want to enter the town. Please save Minamisôma.

March 16th, 2011. 4:40 a.m.

For you, where do you call home? I’ll never abandon this place. It’s everything to me.

March 16th, 2011. 4:44 a.m.

I’m worried about my family’s health. They say that this amount of radiation won’t affect us very soon. Is “not very soon” the opposite of “soon”?

March 16th, 2011. 4:53 a.m.

Well, yes, there’s clearly a border between fact and meaning. Some say that they are opposites.

March 16th, 2011. 5:32 a.m.

On a hot summer day, I like to go to a beach on the Minami-sanriku coast. On that exact spot, the day before yesterday, a hundred thousand bodies washed ashore.

March 16th, 2011. 5:34 a.m.

In a quiet moment, when I try to understand the meaning of this catastrophe, when I try to see it clearly there’s nothing, it’s meaningless, something close to darkness, that’s all.

March 16th, 2011. 10:43 p.m.

Just now, while writing, I heard a rumbling underground. Felt the tremors. I held my breath, kneeled down, and scowled at everything swinging. My life or this tragedy. In the radiation, in the rain, no one but me.

March 16th, 2011. 10:46 p.m.

Do you love someone? If it’s possible that everything we have can be lost in an instant, then all we need to do is to find some other way not to be robbed by the world.

March 16th, 2011. 10:52 p.m.

The world has repeated both its birth and death, sustained by some celestial spirit which defies all meaning.

March 16th, 2011. 10:54 p.m.

My favorite high school gym is being used as a morgue for unidentified bodies. The high school nearby, too.

March 16th, 2011. 10:56 p.m.

I asked my mother and father to evacuate but they couldn’t stand to leave their home. “You should go,” they said to me. I choose them.

March 16th, 2011. 11:10 p.m.

My wife and son have already evacuated. My son calls me. As a father, do I have to decide?

March 16th, 2011. 11:11 p.m.

More and more people are evacuating from this town. I know it’s hard to leave. You can do it.

March 16th, 2011. 11:39 p.m.

Having evacuated to a safe place, the young man, twenty-something, is looking at the monitor and crying, “Don’t give up on our dear Minamisôma,” he says. What’s the sense of things in your hometown? Our hometown now, overcome with suffering, faces distorted by tears.

March 16th, 2011. 11:48 p.m.

Again, big tremors. The aftershocks we were expecting finally came. I was wondering if I should shelter under the stairs or just open the front door. Outside, in the rain, radiation is falling.

March 16th, 2011. 11:50 p.m.

The gas is on empty. Out of water, out of food, out of my mind. Alone in this apartment.

March 16th, 2011. 11:53 p.m.

A long rolling tremor. Let’s place our bets, do you win or do I win? This time I lost but next time, I’ll come out fighting.

March 16th, 2011. 11:54 p.m.

Until now, we carried on the daily lives of generation after generation, we searched for happiness, sincerity, I think.

March 16th, 2011. 11:56 p.m.

My elderly neighbor gave me a box full of onions. He grew them himself. Sadly, I’m not much for onions. The box sits in the entryway, I stare at it silently. A few days ago, I was living my ordinary life.

March 16th, 2011. 11:59 p.m.

12 am. Six days since the disaster. A sick joke! Six days since and for five days, I’ve wanted this all to be fixed.

March 17th, 2011. 12:03 a.m.

In the kitchen. Cleaning up scattered, broken dishes. Aching as I put them one by one into the garbage. Me and the kitchen and the world.

March 17th, 2011. 12:05 a.m.

No night no dawn.

March 17th, 2011. 12:24 a.m.

Ryoichi WAGO (1968–) is a poet and high school Japanese literature teacher from Fukushima City, Japan. In 2017, the French translation of his book, Pebbles of Poetry, won the Nunc Magazine award for best foreign-language poetry collection. Since March 2011, his writing has focused on the ecological devastation of the areas affected by the Tôhoku earthquake, tsunami, and the nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power station. Choirs across Japan sing his poem Abandoned Fukushima as a prayer for hope and renewal.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Alive, the wind

lifts seeds

and carries them away

spider eggs hatch and depart on the wind

over years the wind breaks down plants into soil

we are of the wind and all of our senses

the wind breathing

through us

Within the Trees, A Universe

-Sacred Forest of Kinabatangan, Malaysia

people listen to the trees speak

the trees heard the people

there is light in the woods there was darkness

both life and death

there are voices and so there was silence

within the woods a universe

within the trees a human becomes human

A Mother Speaks

After seeing the noh play, A Killing Stone, Sesshôseki

the play starts in Nasuno province

on the stage there’s a thick purple silk cloth

covering a stone that was dropped

over a field like a cracked rotten egg

a bird flies over the stone and drops

dead to the ground, any living thing, person

or animal that touches that stone dies

a village woman tells the story of this terrifying stone

it starts with her failed attempt to take the emperor’s life

which left her spirit captured within the stone

that now casts spells on the living

when the stone splits open

the village woman appears as a ghost

and the dead return hatching through the stone

pulsing with energy stronger than even the living

the woman’s blaring red rage steadies

and fades to a pale color

the stone again becomes an egg

the defeated become the victors

the lost become found the dead revive

she speaks, the years steal from us

we are robbed of our eggs and escape to the wilderness

we give birth to stone children

hold them in our arms warming the stone

abreast of the thieves who stole our eggs

her ghostly feet glide stamp the ground

a voice within the mask scolds us

echoing from another world

will you be ruled by this bearing always

Rumiko KORA (1932-2021) was a poet, translator, and critic born and raised in Tokyo. Her book The Voice of a Mask won the Contemporary Poetry Prize in 1988. She also wrote essays and novels and co-translated an anthology of poetry from Asia and Africa. She devoted herself to promoting women’s work and was instrumental in establishing the Award for Women Writers. Much of her writing focuses on identifying the struggles and contradictions of a female gender identity.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

SONG FOR AMERICA by Jacques Viau Renaud trans. Ariel Francisco

America, sitting atop the night’s shoulders

singing in the faces of the hungry

deciphering the language of sadness

measuring the modulation of hatred in our children’s stomachs.

America, they’ve stolen your joy

destroying the muscles in your face

tied your heart to the vigil

where thousands of beings wander

inhabited by death,

a death we drag since men, from beyond,

buried his sword, before your name on this earth.

And the dirt

and the mold

and the mud

of our sun-threshed life.

America, get up America

shake off the dust and rust inside you.

America reborn

reborn America

American men,

American women and children

listen to the tremor rumbling from the Antilles

from that stone peak giving birth

to the voice of a child singing from a tiny island

from the hammering of the scaffold

whose shoulders are built from the blows of cackles

and courage

the pure orb of “American love.”

Listen

a new howl fills the sails of America

dragged by the enemies of man

capitalists,

proxies of the temples and Bibles

in the courts of peace and death

so the truth does not burn Bolivia into thirst,

strangled with a clay cord

the heir of the Inca’s

dead on an eternal bonfire

so the light won’t awaken the sleeping quetzal

atop the ruins of aboriginal silence,

to Chile, long and vibrant,

a spear pierced through the heart of an Araucanian;

to Central America

massacred by dynamited bananas,

to Venezuela

where the capital houses their steepest gallows

and the hosts of love are an impenetrable bastion.

To Brazil with large land and few people

adorning their rags with diamonds

tears on the soldiers lapels

while in Argentina and Paraguay

blood clots hang from the commanders medals

and from chimneys rise the stench of crushed meat.

Oh America!

Now without sail

without compass

bent from hunger

bitter fruit fallen

from a shadeless tree

under whose ruined structure

the American licks the back of sadness.

Oh America!

Piece of the dissected chant,

America, America,

reborn America

burdened men of America

light your bonfires

and march towards the light that guards history.

March

inheritors of blood

Colombian cowboys

with their enormous stomachs

where sunflowers bloom.

Natives of Peru

and Ecuador sleepy with coca

raise the ancient face of purity

and tell your secrets.

And you, Puerto Rico

nailed to the jaws of hatred

small lump of sugar plagued by vermin

slow assassination

crushed between masses of metal and glass.

Oh Puerto Rico

I love you more than any other American homeland

because you permanently inhabit the cry

I love you

I love you

I love you from Santo Domingo

dismembered corpse

shout parted in two

but born of a single throat

from a single anguish,

alone.

Oh America

piece of the dissected chant

with a luminous morning

built by the guerillas of love

who have their widest smile in Cuba.

Oh America

for you so many men fight

for you they die

how much love must be housed

to die for you

for an America not yet born

and won’t be for some time.

Americans of the new gospel

hold in your hands

our heart’s clamor

raise high our cry

tighten the knots that tie us to tenderness

the infant dawn of a smile

tied with your veins

wet with your blood

purified by your cry.

Americans of the new gospel

raise high our cry

so it survives the flood

because it will give birth to generations of happiness

an ample mankind

large as the smile of the proletarian sunrise

forever seedlings of vigor

of spilled love

while life edifies

over the debris of a past life.

Americans of 1963, of this century

evangelizers of the new world

raise your heads

raise them high

to see from afar this land that constitutes our future.

With our remains:

with our hands and bones

with our organs,

with all our being,

with this burdened life,

built to survive,

see it

and do not faint

because we are tomorrow’s fire

the eternal youth

the gesture of those who love

giving everything

taking everything

for this life submerged in your voices.

Jacques Viau Renaud (1941—1965) was born in Haiti and raised in the Dominican Republic following his father’s exile in 1948. During the Dominican Revolution of 1965, he joined the rebel forces in support of ousted president Juan Bosch, fighting against the US backed dictatorship. He was killed in battle at age 23.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

THE PIER by Judita Vaičiūnaitė trans. Rimas Uzgiris

Your torn white shirt lies

drying on the anchor.

In the hush of my cheek

I feel your gypsy hair, while husky

voices echo across the water

and through night’s rusting gear.

Palms timidly touch

the still aching secret scars.

Dawn breaks, and in its light

I can see your heart in your eyes,

waiting for me like treasure received…

O dawn – of boundless brutality and beauty!

Judita Vaičiūnaitė (1937-2001) was one of Lithuania’s leading poets of the second half of the twentieth century. She graduated from Vilnius University in 1959, and spent most of her life in Vilnius. She published over twenty books of poetry, as well as translations of poetry, poetry books for children, and plays. She worked as an editor for several leading literary journals in Lithuania. Her poetry has been translated into English, German, Russian and other languages. Shearsman Books (UK) published a selection of her poems in 2018: Vagabond Sun. Her work has garnered numerous prizes, including the Lithuanian Writer’s Union Prize in 2000, and the national award of the Gediminas Cross in 1997.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

TWO POEMS by Stefano d’Arrigo trans. Joe Gross

WHEN MEEK & THUNDEROUS

When meek & thunderous

spring makes its mooring

& the heart wanes in wax,

honeycomb homilies

flit from fin to wing

of migrant fish & birds

wearing whispers of your name;

we imagine you, because it’s true,

your destination, too, is mystery.

OH IN ITALY A MEMORY

Oh in Italy a memory of the women

who turtledove-strut the windowsills

suddenly thresh their thighs

pulverizing poppies in secret

red petals of their Saracen dresses

fluttering like lustful oriflamme

in defense of the footsteps scrawled

over the island’s wind-worn cobbles.

Stefano D’Arrigo (b. 1919, d. 1992) was born and raised in Alì Terme, Messina, Sicily, but lived and worked in Rome as an art critic much of his life. He is the author of the poetry collection Codice siciliano (Sicilian Code, 1957), the epic Horcynus Orca (1975), the novella Cima delle nobildonne (Noblest of Noblewomen, 1985), and Il licantropo e altre prose inedite (The Lycanthrope and Other Unedited Prose, 2010), and played a minor role in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 directorial debut, Accattone.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

J

J