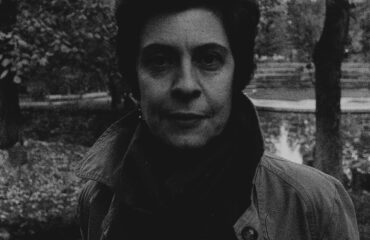

THE HUM by Andrea Jurjević

Hand rapping the dashboard Morse-code style, you approach the intersection of yet another dust-caked town where the red lights seem to always flash. The cigarette wedged between your index and middle finger ashes across your shirt sleeve, your pale thumb bending so far back it looks like a U-turn. Against the black fingerless glove, the curve of your thumb seems even more exaggerated, almost alarming. You scan the crossing and proceed right through. I tune into the drum of rain on the car roof. With Macon behind us, home is just a dreary hour and a half away.

“Don’t you know I can’t be around people who drink?” you say, over-enunciating each word.

“No one was drinking, baby,” I respond. “People had a beer while waiting for a table, that’s all,” I add in my best conciliatory voice.

“You don’t get it, Mirela. I almost died a million times!”

“I was just talking to friends I haven’t seen in ages. After the film screening, everyone went next door to grab a bite.” I repeat what I already told you on the way to the car. “I stood there with no drink,” I lie, “and had a quick chat with Misty while they waited for a table. It was a big day for her. And you went out to smoke, anyway.”

“Yes! And I waited for forty minutes! Forty fucking minutes!” you go on, progressively louder.

“Oh, c’mon, Eric. Is that such a big deal? We never go out anyway.” My voice swerves, and I hate it for that.

“You don’t understand what I went through. You just don’t get what hitting rock bottom is like, do you?” You look at me coldly, the corner of your mouth pulled up and back.

“Right,” I snap. “I don’t know squat about life and struggle.” I turn away from you and look out the window. It’s getting dark. In the failing light, the trees lining the road are a procession of shrouded, mournful widows. “Turn on the headlights,” I say to you, and the next moment the car is swiping down the wet road like a thief with a flashlight.

“I suffered in order to stay alive,” you go on, increasingly impatient. “I was at the bottom of the pit, Mirela, crushed with pain! Do you have any idea what I had to live through, the hospitals, the psychological abyss, weeks spent in blackouts, how hard it was to quit? Do you fucking get it, Mirela?” you ask, slamming the steering wheel, ashes falling down your knees. “You have to understand something.” You point your finger at me. “I have far too much damn gratitude for being here with eyes clear and heart still beating to let—”

Unimpressed, I tuck my hands under my armpits. I try not to pay attention to you and concentrate on the hum of the rain filling the car.

“You know what,” you interrupt the pause. “Never fucking mind. I’m done. I am done with this bullshit!”

“What in particular are you done with, Eric? Me talking to people?”

“Fuck this, I’m calling Scott.” You light another cigarette and call your sponsor, but the call goes straight to voicemail. “I’m starved. And now everything’s closed in these shithole towns.”

“The pub was open,” I say, and mutter to myself, “but that was too much human interaction for you.”

“What was that?”

“Nothing.”

“I need to get cigarettes. I’ll stop at a gas station, and I’ll pick up a frozen pizza.”

“Let’s stop in a grocery store when we get back to the city and pick up salad greens, some Manchego, smoked salmon, and fresh bread and make a nice dinner.”

Steering wheel between your knees, you throw your hands into the air, cigarette ashes now falling across your jacket. “Why do you always have to be so high maintenance?”

“Me high maintenance? I work seven days a week running the community music school, raise my children, do all the cooking and house chores, while you sleep in and go to your meetings. And I am high maintenance?”

When I hear myself fight in English, my voice sounds backless, the words as if they’d been trapped too long in my gut, cold and lifeless like sea cucumbers.

“Oh, so you’re not happy,” you say. “Get off your high horse, Mirela! You knew who I was when we met, so stop telling me how to live. And for the last time—I am working on my memoir! I’ve got a hell of a book in me.”

“You just love stewing in your own funk.”

“Bullshit. I’ve done more work on myself than you can ever imagine!” You turn on the radio.

A loud jingle comes through. “Serving the body of Christ! Join us for the worship every morning and evening. We meet—” Your curved thumb frantically taps on the search button when another voice slips into the car. “Your favorite Georgia country station brings Morgan Wallen and ‘Whiskey Glasses.’”

“Goddamn South!” You stick your hand into the console and pull out a System of a Down CD. A gallop of distorted guitar and dense bass surges from the speakers. A moment later you turn the music off. The sound of the rain fills the car yet again and drowns your words into an incomprehensible mutter.

We are still over an hour away from the city. My hands feel dry as dust. My entire body is uncomfortably confined. I fumble through my purse and pull out a tube of lotion. I rub my hands with the slippery cream, as if reviving a dead heart. I thumb my left palm, then the right one, roll each finger. I take the lip balm from my pocket, spread it across my lips, then break off the top and massage it into my cuticles. The car is a trapped cloud of cigarette smoke and rain hum, and the seat belt is cutting into my abdomen. I undo a couple buttons on my blouse and pull up my sleeves. I drink icy water from the bottle in the cupholder. I pour that water on my palm, rub it into the back of my neck, inside my blouse, and lean my head against the window. I can hear you complain, but I’m concentrating on the rain. Your voice sounds distant, muffled, as if I’m swimming underwater and you’re on the shore, wildly gesticulating and yelling something at me.

My phone lights up from my lap. It’s Misty.

Where are you, girl?? We got a table in the back room. The big corner booth.

For a simmering minute all I want is to dip—swing the car door open, release myself, be gone. To dart like a deer, weightless among the dark trunks of birch and ash, run soundless over the wet detritus. To slink among hazy shadows. Instead, I turn the phone off without responding and slide it into the purse laying slack on the ground next to my feet. I close my eyes and think of my old home on the island of Rab, how quickly weather would sometimes change. One moment I’d be looking at the sea, still as oil, and the next a big black cloud would roll in, a strong wind would manifest out of thin air, and the sea would become a big screaming mouth, all spit, foam, and piercing rage. I’d be running around, pulling the kids’ toys into the house, ripping laundry off the clothesline, closing the shutters on the windows so they wouldn’t get ripped off the house. My skirt would balloon and lift past my waist; my hair waved up like a flame. The island would’ve sailed away in that weather if it just had a rudder.

That old house with its square face has been closed for years, its breath musty, the attic still holding newspapers from decades ago, never-used handmade bedding dowery, my grandparents’ glass bedpan caked with dust. I think back to my kids when they were little, how much they loved swimming in the narrow inlet down the road when we’d visit. Luka would doggy-paddle ahead of me, the sea washing his face as if in ablution, and Lola would ride on my back, gripping my neck tight. Luka would kick his feet furiously, wiping away everything in his path, unafraid of the depth underneath his body. The sea always sparkled like wine, and I can still smell the pine trees lining the shore. The cypress, too. And the rosemary.

When I was a girl, I used to pick currants by the retaining wall with Nona, my fingers stained with the red tangy juice. Except for the short, pure chirp of crickets, we worked in silence. The berries would be sticky with spider webs and insects, and I was frightened of snakes, especially the slender black whip snakes. Sometimes when they would slither out of the invisible tunnels below the dry dirt, Nona would greet them with the sharp edge of her hoe. Even after their bodies would be cut in two, the sliced remains continued to slither and thrash about, and their heads, decapitated, would go on hissing.

Oh, Eric, you make me long for the place I left.

Your face is pinched and flushed now, the purple vein on your pale temple bulging. “It’s been twelve years, long before I knew you,” you’re screaming, “over four thousand days of waking up without a hangover, and you do not understand,” you say—though I do, buddy, I do.

For the two years we’ve been living together, I’ve been bottling and arranging my feelings as if they were items in an old-school apothecary: herbal brandy, bitter teas, tinctures of wild oregano, restharrow root, black horehound crushed in the belly of the mortar, dark tonics of resentment. Remedies for bad docking.

***

After I met you, Misty asked one question after another: “But why pick an alcoholic?” (He is sober.) “Does he have a job?” (He will.) “Are you going to need to support him?” (Possibly.) “What is it, your heart telling you that this is it again?” (He’s a real deal. He drives all night from Philly to see me.) She was silent for a long time. “How is he with the kids?” (He plays Fortnite with Luka. He gave Lola a nice beaded bracelet for her birthday.) “Mirela, put yourself and your children first, not some man you don’t know.” I didn’t care. Misty knew nothing of aloneness in a foreign country. About the dark waters brimming underneath the surface of a new love, something so amniotic I wanted to curl up and float in it.

You drive up the highway and take the next exit. A tall sign with a glowing clown-red heart juts out from the dark skyline. Love’s Travel Stops. Its reflection on the windshield flickers in rings of light. My chest feels tight, throat dry, as if I’m carrying a clod of dirt within me. Everything seems far off, like listening to an old recording of one’s own voice, a self you can barely remember. My first twenty years abroad I had been hopeful. I followed my heart, a man, to the States. I went back to school, learned the English language, started my own family. Back then, I believed wonderful things awaited me as long as I followed my conscience, did what was right. But what’s right?

You pass the long line of parked 18-wheelers, circle around the island of bright gas pumps, and park the car near the entrance of the convenience store.

“I’m getting my goddamn cigarettes and pizza,” you say, slam the car door, and disappear behind the glass entry with a flickering blue Budweiser sign.

***

“She’s a mother with two teenage children,” your mother warned you. She was phoning in from her vacation with her new friend at yet another healing center, in Maui or Machu Picchu, I forget which. “They are a family. It will be a big change for you, darling. Are you up for the challenge? The responsibility of stepparenting? You know I want what’s best for you, honey.”

You nodded, dismissing her concerns, then gave her a big cheesy grin she couldn’t see. “I love her so much,” you said. “She’s the one, Mom. We will figure it out. The kids need to see someone spoiling the shit out of their mother. And they’re good kids. We already get along.”

My heart is pounding furiously, eyes glued to the sliding glass doors. A couple of sun-burned, middle-aged blonds with claw clips in their hair pass by my side of the car on the way out of the store, laughing loudly. I can see the sickly-looking attendant working slowly behind the cash register and a long line of people that vanishes between the isles of snacks. In the side mirror I see a man with Georgia Bulldogs stickers on the windshield of his truck filling up his tank and scrolling on his phone. A blue Ford pick-up with a confederate flag license plate pulls out from the spot next to me. One moment passes, then two. Another car pulls in next to mine. A swanky black sedan. A curvy woman in a blinged velvet tracksuit opens the passenger door, letting out a blast of trap music and a bubble of weed fumes from the dark interior. The fragmented sounds and lights fuse into a bright buzz. They get louder, and I can’t tell which direction they come from. The whole world collapses into the fullness of that noise and becomes entirely real: this night, that sleepy town where Misty is toasting to her dreams coming true, her directorial debut, me in the passenger seat of my own car, the stench of your cigarettes, and beyond this gas station, the rumble of the highway traffic and the silky call of rain. My ear is attuned to it like to a distant radio station.

***

I remember Nona in the garden to the right side of our square-faced house, among chicory and chard, hoeing sharp rocks out of scorched dirt, her face shielded by the soft blue cloud of her hair. Nono was usually lost in fixing the nets, quiet as a summer afternoon. But sometimes there’d be blue skies and furious silence. You could hear it coming—the hum. At first a low-pitch rumble would raise from under his breath, or from beyond the clouds. Hmm, hmm, hmmm. Then it would grow more resonant. When Nona would hear it, she’d get nervous and promptly shush me. “Zitto, Mirela!” She’d look up at the distance and say, “There’s going to be trouble.” And in a spell, the sky would turn dark and a cold, dry wind would roll down the mountain range. Nona would nod in the direction of Nono and the clouds, and she’d say, “The whole house will need rebuilding.”

I remove my seat belt, lift my left leg over the console, then the right, and slide onto the driver seat. I pull up the lever underneath the seat and move it forward. I adjust the height, check the mirrors, turn on the engine and, without turning the lights on just yet, carefully back the car up. I drive to the right, towards the flow of traffic, the road that leads back to the freeway and to the city cloaked in the calm emerald of the night. As I pass the patch of grass with empty flower boxes and the tall Love sign, I slow down, my right hand firm on the gearstick. The sign must be at least ten meters high. At the top of it, in the pitch dark, the red heart glows like a lighthouse at night.