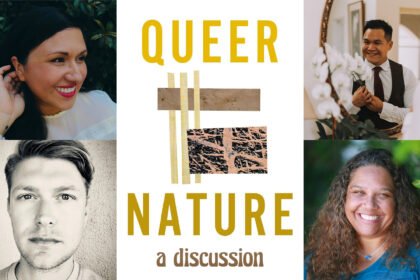

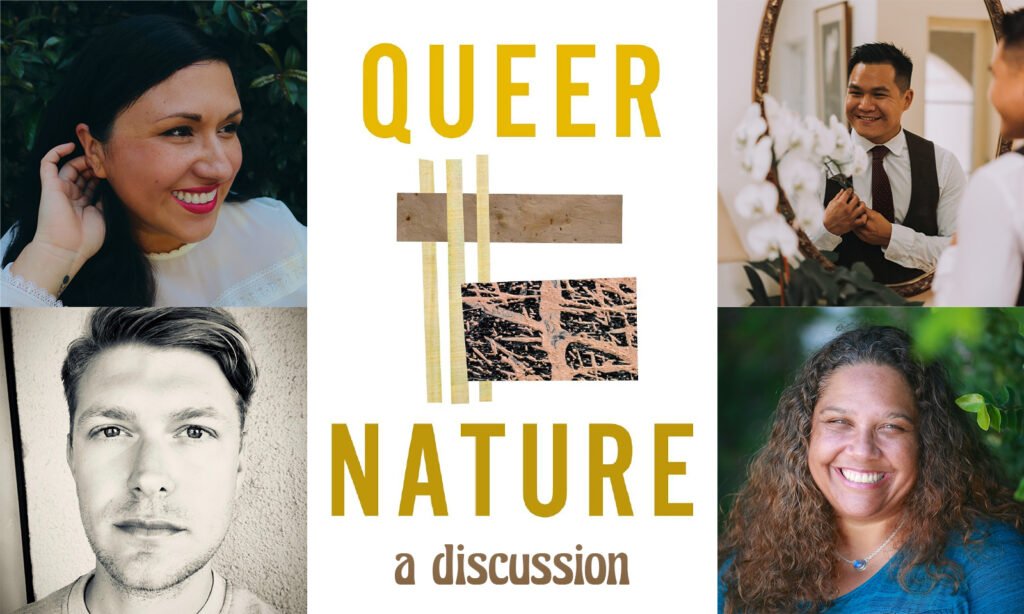

QUEER NATURE ROUNDTABLE

In 2021, Four Way Review partnered with several other journals and presses to establish the Bootleg Reading Series. It was a partnership we hoped would continue to grow beyond the reading series and lift up the projects of each partner. We’re excited to share this conversation with some of the poets of the new Queer Nature anthology, published by Bootleg partner Autumn House Press, in conversation with one another and the ideas of “queer nature”.

“Queer Nature is a groundbreaking anthology of more than 200 LGBTQIA+ poets writing about nature. Left out of the canon but with much to say, these writers peculiarize bodies into landscapes, lament the world we are destroying, and sing of darkness and love, especially along the beach. If nature is a monocrop, no single aesthetic, attitude or voice defines these poems from three centuries of American poetry.”

Michael Walsh, editor of Queer Nature, is a 2022 Lambda Gay Poetry Finalist. He received his BA in English from Knox College and his MFA in Creative and Professional Writing from the University of Minnesota—Twin Cities.

FWR: Which queer poets have inspired you? Which queer poems? If any are pastoral, do you notice anything new about them in the context of queer nature?

“You know, I have a lot of embarrassment about being pretty under informed about poetic movements or styles. I studied English and creative writing, but thought more about individual poems. This is just to say I’m not certain I understand what the pastoral is, but I do love a lot of poems that figure and transfigure the natural world. I think of poems like “Tiara” by Mark Doty, which puts drag queens next to lush water, next to death and sex.”

Eric Tran earned his MFA from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and is the author of Mouth, Sugar, and Smoke (2022), forthcoming from Diode Editions in the spring, and The Gutter Spread Guide to Prayer (2020), from Autumn House Press. He is also an Associate Editor for Orison Books and a resident physician in psychiatry at the Mountain Area Health Education Center.

“I consider poets like Elizabeth Bishop and Audre Lorde to be major influences in my development as a poet. I was introduced to both poets in college and graduate school. My first attempts to write about my own queer experience were influenced by “The Shampoo” by Bishop, in which the simple act of washing her lover’s hair inspires an image of shooting stars, suggesting to my young mind that love between two women is such a revelation that it compels images of heaven. The movement toward metaphor in this poem was indicative of the deep nature of a sexual relationship between two women. I experienced the same sense of revelation in Lorde’s “Love Poem” where intimacy pushes the speaker toward seeing her lover’s body as a forest and her own entry into it as the wind, as she opens widely to “swing out over the earth over and over again.” As an imagistic writer, I struggled to write about sex in an overt way; however, the metaphor invites great possibilities for writing about intimacy between women.

“Neither of these poems is pastoral; however, you ask an interesting question in the context of environmental poetry. Much of the nature poetry being written today is a movement away from pastoral writing. There is too much that stands in the way of the effort to ‘touch’ God through one’s experience of nature—abuses of the land, water, and air, not to mention our current focus on the power of place where the land itself has connection to indigenous peoples and histories that far more important to acknowledge, at least in my mind.”

Amber Flora Thomas earned her MFA at Washington University in St. Louis and is the author of Red Channel in the Rupture (2018) from Red Hen Press, The Rabbits Could Sing (2012) from the University of Alaska Press, and the Eye of Water (2005) from the University of Pittsburgh Press, which won the 2004 Cave Canem Poetry Prize. She is also the recipient of the Richard Peterson Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize from Rosebud magazine, and the Ann Stanford Poetry Prize.

“My poetry would not exist without the poems of [Constantine] Cavafy; his dreamy stagings of sex and history are always close to me; his frankness and the undramatic way his poems unfold have taught me so much about managing energy in short lyrics. James Merrill was the first poet I loved unreasonably. Henri Cole and Carl Phillips are two poets of my parents’ generation whose work has been indispensable to me from the beginning. They are both represented with brilliant poems in the Queer Nature anthology—both poems in some way about the way we look to the natural world to teach us about ourselves, our desires, and how the natural world always complies and refuses us at the same time.”

Richie Hofmann is the author of A Hundred Lovers (2022) from Alfred A. Knopf, and Second Empire (2015), from Alice James Books. He received his MFA at John Hopkins University and is a Jones Lecturer in poetry at Stanford University.

“The queer poets and academics whose work has been foundational in critiquing Western constructions of Nature (and thus The Human) in my work are Sylvia Wynter, Katherine McKittrick’s Demonic Grounds, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson’s Becoming Human, Gloria Anzaldua, Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem, Vievee Francis’ Forest Primeval, Jake Skeets’ Eyes Bottle-Dark and a Mounthful of Flowers, and Natalie Diaz’ Postcolonial Love Poem.

“These works reveal how the “Nature” of the Western imagination is an inherently colonial concept. “Nature” conceived as terra nullius, or empty “virgin” land, by using the very word, invents the land as an unpeopled, undisturbed habitat outside of time, removed from the urban, and evacuated of Blackness, indigeneity, and queerness. National parks—“America’s Best Idea”—are racialized spaces defined by the absence of race, and serve to dehistoricize the land from its indigenous history and frame conservation as a value rooted in rugged individualism and self-sufficiency. In the construct of “nature,” indigenous people are confined to prehistory—if nature is prehistoric, then what we do to it does not affect our future. In the Western imagination, “Nature” is separate from us, just as the body is separate from the mind, and becomes an object—a place to go, a thing to be experienced, a resource to extract from—rather than a living being surrounding us, full of beings with whom we share a destiny. The concept of “Nature” is primitive, and necessary to construct the (white, Western) Human who has evolved beyond it.”

Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, author of award-winning Beast Meridian (2017) from Noemi Press and essay collection CHUECA, forthcoming from Tiny Reparations Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, in 2023. She is a recipient of a 2021 National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship and PhD candidate at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

I think animals abound in queer poems as metaphors, false or correct, of fully living in a body.

FWR: Queer desire carries an inherent subversion of expectation, and with it, potentially, greater freedom of form and image. What are “the birds and the bees” of queer erotic poems? What metaphors are found in the biomes of queer poems, especially sexy ones?

AFT: I have been trying to find my own answer to this question. I have written about my experiences as a child of retreating to the woods as a place of safety. Often, I would find myself hiding in the woods where I could watch my family, seeing through the trees a world that could not embrace my queerness. I take my queerness to the woods where it is not moralistically judged by the trees or other flora. This question reminds me of Carl Phillips poetry and essay, especially his “Beautiful Dreamer” chapter in The Art of Daring, which describes stumbling on three men having sex against a tree in the woods. Perhaps the wilderness provides cover or separation from societal judgement, which is why we have so much to say about queerness and nature.

VAV: Nature was never accessible to me growing up—I was born on the US/Mexico border and grew up in Houston, Texas, an ever-sprawling, drowning city under construction where Nature is at least an hour drive away near the state prison, and where white flight takes its suburbs and fells trees to make room for endless strip malls and megachurches.

Still, nature asserted itself in surprising and subtle ways in the Black, Latine, and queer neighborhoods of Houston where I grew up. My childhood home is near Acres Homes—a historic Black homestead nestled between highways, famous for its barbecue and horse-mounted Black cowboys; I attended Pride at seventeen and got my first HIV test at the free clinic in Montrose, the (now fully-gentrified) historic gayborhood of Houston along Buffalo Bayou; I biked through the white-oak-lined side streets of Third Ward, Houston’s historic Black neighborhood, to attend the University of Houston. And as a child, the swampy young pines behind our house haunted my imagination and stayed with me long enough to inspire the inner nightlands of Beast Meridian.

Those pines were where I escaped the confines of gender and jumped my bike over ditches with boys, smoked cigarettes and listened to music with the bad kids, escaped angry parents to read The Bell Jar under honeysuckle, tagged anarchy symbols under bridges, explored flooded creeks and caught crawfish when the power was out after hurricanes, kissed and touched and undressed with every gender under the stars. After I got caught sneaking out at thirteen, my parents took my bedroom door off its hinges permanently, so throughout adolescence, the pines were the only place I had any privacy, the place where I became brave, the place that held my forbidden self, a sanctuary of desire that made safe my secrets, the moonlit clearing where young love blossomed in my body, a haven for a young girl in trouble to hide. My girl, my girl, don’t lie to me, tell me where did you sleep last night / In the pines, in the pines, where the sun don’t ever shine, I would shiver the whole night through. That vision of nature informs every poem in Beast Meridian, from “Malinche” to “Girlbody Gift” to the final sequence, “The Way Back”—the nightlands of forbidden desire, rebellion, trouble, alienation—where the speaker grieves her monstrosity until she can finally embrace her animal, and in so doing, sets herself free.

Queer nature is a catapult out of the limits of a single human body. It is a breaking out, a widening into the possibilities of a transformative understanding of boundaries of self.

RH: Being queer, I think, forces one deeply into one’s body—you become more aware than other people about the arbitrariness of gender and the randomness of having a body. I think animals abound in queer poems as metaphors, false or correct, of fully living in a body. Free from desire and emotional pain, social torment, strictures of marriage and morality. In my own poem, “Idyll,” the speaker desires to shed his skin; the act of speaking, of confessing to desire, is an act of undressing.

ET: I love this definition of queer. I think sometimes we think of queer as undoing or transforming, but often I think of queer as revealing what has always been. Rather than leaps, I think of sinking deeper into, of falling, of lying and pressing (as fingers into the soil)–all of which are unsurprisingly very sexy actions to take.

FWR: What does queer nature mean to you? If you experienced the HIV/AIDS pandemic, has experiencing the Covid-19 pandemic caused you to consider “nature” more than in the past?

RH: This is a hard question for me. I feel somewhat ambivalent about both “queerness” and “nature.” I don’t think of myself as a pastoral poet. I’d rather be in a museum than in a forest. But reading Queer Nature, I feel such a profound kinship with writers I’ve never met.

AFT: Queer nature is a catapult out of the limits of a single human body. It is a breaking out, a widening into the possibilities of a transformative understanding of boundaries of self.

I don’t have much to say about the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the Covid pandemic. It angers me that most people still think of HIV/AIDS as a ‘gay’ disease. Most people do not see the parallels. Most people can’t get to the point where they see how greed, environmental degradation, and ignorance lead to pandemics.

the act of creation is forever fused with subversion in nature

VAV: The nature of my youth was not the normative Nature of national parks or state reserves—it was a nameless, swampy half-acre of undeveloped land behind our house, where flooded ditches gouged the boundary between our neighborhood and the trailer park next door. That nature was where the “bad kids”—the troubled kids, rebels, outcasts, queer kids—found each other, not recognizing that our bond was not in our badness, but in shared trauma and alienation. The only way to get to our nature, queer nature, was to be disobedient, daring enough to break a rule, stay out after hours, trespass, know where to jump the fence. The forbidden places I went to skip school, smoke cigarettes, skinny dip, drop acid, give and get head, kiss both girls and boys, fuck in cars until police pulled up, were also where I went to read, write, and play guitar. And this has had a fundamental influence on my artistic practice—the act of creation is forever fused with subversion in nature. Nature and art are sites of disobedience, rebellion, and provocation—if I am not being subversive, vulnerable, provocative, brave, then I am not making the art I want to make.

Now in single motherhood, I live near Griffith Park and Southern California beaches, and nature is a haven from isolation and endless responsibility, an expansive companion that quiets my troubled heart, holds my grief in rosy light, and sends me guardians to guide my path—still deer, scrappy coyotes, vigilant owls, hovering hummingbirds, tumbling dolphins, fragrant artemisia—their presence urging me to go on when the world feels impossible and love never comes. Now, nature is where I go to slow down time and listen to the open, be with when there is no one, be with until there is.

ET: I think queer nature asks about access and owning and belonging. I think in both of these epidemics, we had to reckon with the truth that very little is owed to us and in fact, we are obligated to return our bodies to the natural world eventually. That sounds very bleak but what I mean is that my idea of queer nature is to be freed of invented obligation and restriction and to discover and experience what is opened.