QUARTO: Tribute to Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan

_________________________________________

Saturday Morning: Remembering Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan by Addrienne Su

“This is How I Remember Her” by Blas Falconer

_________________________________________

Vievee Francis in LA Review of Books

Contributing Editor Vievee Francis talks with the Los Angeles Review of Books.

“IN FOREST PRIMEVAL, winner of the 2017 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, Vievee Francis summons a wilderness — equal parts the wilderness of America and the wilderness of the interior — that takes us off center. I know and love that particular North Carolina wild that Vievee has described, having lived in the Blue Ridge Mountains myself for a stint, too. Vievee and I have both since left those mountains, and during our conversation, which took place during her weeklong residency at Claremont Graduate University, we laughed about living in a place where there might be snakes on the porch or stinkbugs nestled in the curtains. That is, a place where that wild thing in the world and in the self feels nakedly present and abundant; one has to face it. And it is so, in this book: a segue from Vievee’s vivid persona poems, those extraordinary masks, into an articulation of her own personhood — a speaking of the black female body, this marvelous, terrified, joyful assertion of her name in a broken country that would otherwise un-speak it.”

Read at LARB.

- Published in home, Uncategorized

PUSHCART NOMINEES

We’re proud to announce our 2017 Pushcart Prize nominees!

From Issue 9

This is why I Need a Goddess by Angela Penaredondo

Lambing by George Kalamaras

Mare Frigoris by Rachel Brownson

From Issue 10

Reprieve by Jenny George

Argument for Loving from a Distance by Katie Condon

Drinking Game by Marlin M. Jenkins

- Published in home, Uncategorized

FWR Monthly: September 2015

Meditation frequently asks its practitioners to ground themselves in their bodies through a series of structured “noticings.” You are gently urged to press yourself into your chair, press your feet into the floor, press your fingertips together, press your lungs out into their little cage of ribs.

It is easiest, it turns out, to notice your body when it meets with a measure of resistance. The floor is a fact your feet cannot change. To live in a body, we are told and retold, is to forget about this all the time.

When I solicited poems for this issue, I asked for work that “enacts or inscribes the feminine in fresh, unusual, or surprising ways.” Noting that gender is both inscribed upon the body and enacted by the body, I wanted to see how gender could visit the text, or the site of inscription. It is, in fact, near-impossible for many of us to forget about our bodies. This is not a failure to live within them, but a ricochet from resistance to resistance, reminder to reminder – “You do not inhabit this body. To the world’s eyes you are this body. Here is what that means.”

I’m delighted by the poems in this issue, in no small way because they make the original phrasing of my solicitation seem deeply small and beside the point. They embrace the mystic and the vulgar. They are funny, heartbroken, and kind. They dig deep for inner voice and reassemble the voices around them in a gorgeous echolalia. With plums. And hoofprints. And Kim Kardashian. I hope you like them.

Kate DeBolt

Assistant Poetry Editor

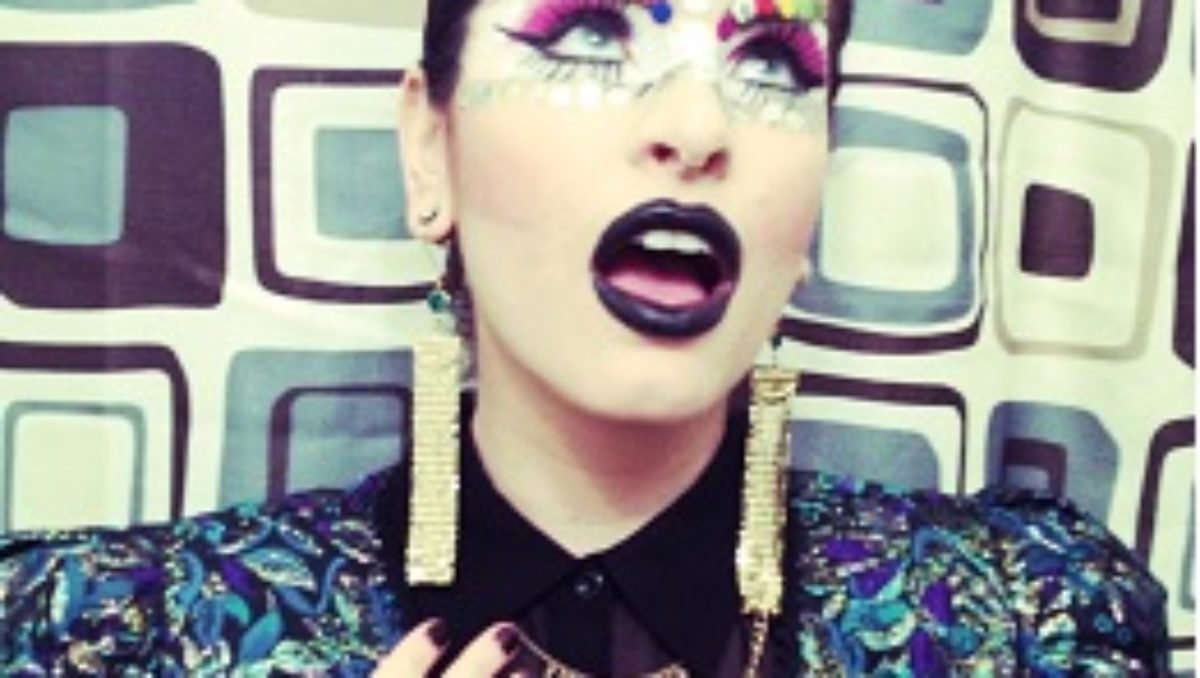

DRAG NOTES – FROM A CONVERSATION WITH KINGA

by Justin Engles

TWO POEMS

by Danielle Mitchell

THREE POEMS

by Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

PRAYER TO ST. MARTHA

by Leah Silvieus

Artwork by Lexi Braun

- Published in home, Monthly, Uncategorized

FWR Monthly: August 2015

The idea of voice has been hot on my mind lately. I think the ongoing work of folks like Amanda Johnston (one of the founders of Black Poets Speak Out), has made me think closely about how I move through the world, speak for myself, for and with others. Voice is subjective, relative. It’s also incredibly relational. Although I’m not a thousand percent behind Naomi Wolf’s talk of vocal fry, I know well the phenomenon of adapting one’s voice to suit one’s audience. The question is, then, from which conventions and collectives does one draw? And why? A writer performs on the page for a hypothetical audience, introducing herself to strangers again and again. Whatever voice that writer inhabits at any given time should be considered and relevant, and it should always feel true.

Since this is my first monthly curation of Four Way Review, the theme feels apt. As editors, we think about our own voices, our voices in conjunction with other editors’, and how the pieces we celebrate reflect upon us. Last month, Ken Chen, Executive Director of the phenomenal Asian American Writers Workshop, wrote an article excoriating certain white artists whose so-called transgressive work does little more than parrot the language of violence, racism, and patriarchy. Another recent editorial at Apogee raises the idea that it is as impossible – and unethical – to “read blind” as an editor as it is to be colorblind in the way we engage with each other in the flesh.

Here’s my secret: I was a little tempted to name this issue The Anti-Rachel Dolezal Life & Times, for the sake of those of us who have worked very hard to be ourselves, to own where we come from, and to make art from that space. The aforementioned – now-infamous – identity thief, who has worked with visual media in the past, was, unsurprisingly, once accused of plagiarizing a landscape by another painter. The appropriation of style, voice, and culture all converge so neatly in her story, it’s remarkable.

With all of this roiling in my head, I found myself, more than anything, wanting to read gorgeous, powerful voice. Just that. Inventive, not necessarily confessional, but representative of the artist in an elemental, charged way. When I started feeling tired of tired voices, avery r. young and Juliana Delgado Lopera came to my mind immediately, as the balm I wanted and needed most.

I bet you’re going to like reading these folks. Their styles are very different: young’s work boasts spareness and abbreviation, often using the architecture of parentheses to slow the reader, to encourage and reward re-reading. Lopera’s narrator, on the other hand, has fluidity and grace that’s enviable. Both are immediate. Neither backs down.

It wasn’t planned, but I don’t find it at all surprising that, in young’s suite of poems and Lopera’s excerpt, both use Christianity as a springboard for their characters’ voices. Owning one’s voice often comes from looking directly at structures of power, the stories we as a culture swear by. I think it’s important to reclaim power this way. And maybe it seems naïve, but I feel the connection between the art we make and support and the way we engage each other in the world is very real. These two artists are doing the good work.

~ Laura Swearingen-Steadwell

Poetry Editor

excerpt from FIEBRE TROPICAL

by Juliana Delgado Lopera

NEW TESTAMENT

by avery r. young

- Published in home, Monthly, Uncategorized

FWR Monthly: July 2015

For this installment of our new monthly “mini-issues,” I wanted to present a small folio on a genre which seems to gain more and more attention, particularly among poets — the “photo-essay.” Because so much of our daily life has gone digital, it becomes harder not to primarily encounter the world through our sense of sight. And “seeing” isn’t easy. For the photographer, when a photo essay is being built, he or she must whittle down, sometimes from hundreds of photos, until the image is found; then he or she must find other images that create tension with that original image. This month’s Monthly will present you with two poet/photographers, Chris Abani and Rachel Eliza Griffiths, both of whom I believe are doing fascinating and challenging work through photography. And please read the interview I conducted with Rachel! Such wonderful answers. That said, have a look-see (ha, see what I did there), and thank you for reading.

~ Nathan McClain

Poetry Editor

ON THE PHOTOGRAPH: AN INTERVIEW

with Rachel Eliza Griffiths

GHOSTING, INVISIBILITY AND THE ERASURE OF PARTICULAR BODIES: A SPELL

by Chris Abani

ARTWORK by Krithika Sathyamurthy

- Published in Uncategorized

FWR Monthly: May 2015

Starting this spring, we’ll be sending our subscribers monthly “mini-issues,” each one edited by different members of our staff. We see these monthlies as a chance to showcase more great work, and explore more topics of interest, than we have room for in our regular biannual issues.

To kick things off, I’ve chosen work that blurs the sometimes arbitrary boundary between poetry and prose. As a reader, editor, and writer, I’m most interested in work that blends the finest elements of both — the kind of work in which one hears, as Robert Frost once called it, the “sound of sense.”

I hope you like these “poems” and “stories” just as much as I do, and will keep an eye out next month for a brand new feature, chosen by a different member of our team. Until then, thanks for reading.

~ Ryan Burden

Managing / Fiction Editor

TWO STORIES

by Kevin McIlvoy

THE LUTHIER’S MOTHER’S MOUTH’S OPENNESS

The Luthier’s mother’s mouth’s openness, her hands’ finger’s

tremblings, her red hair’s fires’ warnings. It’s what you saw if you

were making your last visit to her ever. You were the Luthier’s

mother’s Possession when you walked into her son’s guitars’

home, in which son and mother also lived together in one room.

Inside their home’s heart’s sounds: the tub’s faucet’s dripping’s

splashings and the refrigerator’s coils’ hymning humming…

TWO POEMS

by Sierra Golden

LIGHT BOAT

Jesse isn’t really a pirate, but the Coast Guard thinks so when he calls to say he found a body. It doesn’t matter that she’s still alive, so cold she stopped shivering, blue fat of her naked body waxy and blooming red patches where his hands grabbed and hauled her from the water. He stands over her with a filet knife, slowly honing the blade as he waits for Search and Rescue. The glassy eyes of a dead tuna stare up from the galley counter. At dusk, Jesse flicks on the squid lights…

Between the Lines: An Interview with Benjamin Miller

In this installment of “Between the Lines,” Dustin Pearson talks with Benjamin Miller about journeys through the desert, words as objects, and poetic self-interrogation.

DP: A lot of the poems in your collection share the same titles. The title in common I found most central was “Desert.” Between the appearance of the first “Desert” and the last, the speaker seems occupied with the idea of having done or doing nothing. My mind immediately associates those poems with Moses’ liberation of the Israelites from Egypt, but I struggle to draw an explicit connection considering the different circumstances by which the two journeys are provoked. How do you imagine the connection, if any?

BM: I did put that title there with a biblical text in mind, but it was Abraham I was thinking of, not Moses. Or, at least, Abraham most of all. He’s told by God, not once but twice (Genesis 12:1, 22:2) to get up, go, find himself, don’t worry about where, God will show you. And that idea of journeying without knowing where you’re going is what appealed to me, the being drawn forward, but where are you the whole time? You’re in this desert, this vast and isolated space. And you don’t know if you’re close or far, or if in fact you’ve traveled any great distance at all, because the light plays tricks.

Now, I know the poems themselves don’t enact that exactly: there are trees and windows and clocks and doorlocks and couches and things.

Part of it, I confess, is that this title came late to this series of poems. Originally these were days of the week, starting I think with a Wednesday, which generated the wolves who chase the sun. But another part is just a function of how I compose, which often involves taking words or objects (or words as objects) and playing with them — subsetting them, rearranging letters, thinking of their opposites and apposites — and trying to get them to yield up some insight or emotional understanding I hadn’t had before. So the couches and the bathroom door cracks and the days started out as real, but they took me to that lonely place where I could see the lines being part of this series of poems, even if the narrative of the text itself isn’t set in the desert.

DP: Your collection seems to be sensitive to the coming of night and morning, the idea of home, and especially return and arrival. I most readily think of your poem “Field Glass (Manifest)” as a good example of all these themes working simultaneously. Can you comment on what inspired this? How conscious or unconscious are their recurrence? Did that element of consciousness change over time?

BM: It did become more conscious over time. The poem you mention was written in more or less one quick outpouring, though it did get a lot cut out of it afterward, and some minor revisions made. (Other poems have had a much more belabored history.) So that wasn’t a deliberate attempt to include these themes; it just was the headspace or wordspace I was in at the time. But in my MFA thesis workshop, we were put on “word watches” by Lucie Brock-Broido; I think I also had wings and lightning and dark, which I was happy to cut back on because I didn’t want the whole book to be too, too, well, for lack of a better word, emo. But I think it was around then, seeing the consistent presence of departure, travel, sand, light, that I began to think of the book as cohering around the Abrahamic journeys I mentioned earlier, and to look for more ways to build those up: more deserts, more field glasses, more sand.

DP: The interviews in your collection are among the most fascinating and difficult poems. Can you comment on how you imagine your readers accessing these poems?

BM: Though you might not know it to look at the pages, much of the book was written under the star of W.S. Merwin’s The Lice and The Moving Target; his “Noah’s Raven” was one of the first poems I remember learning by heart, and its spirit floats over the waters of my deserts. These interviews bear clear traces of Merwin’s “Some Last Questions,” which I’ll quote a little of if I’m allowed:

What is the head

A. Ash

What are the eyes

A. The wells have fallen in and have

Inhabitants

What are the feet

A. Thumbs left after the auction

No what are the feet

A. Under them the impossible road is moving

Down which the broken necked mice push

Balls of blood with their noses

and so on. As in other cases, what I think we’re both doing is trying to re-see the significance of something right in front of us, whether it’s parts of the body or parts of words. It’s a self-interrogation, a self-spurring onward beyond the first impression. When I write,

What is the sun?

A single star does not define an evening.

I really am trying to answer the question, but to use the search for an answer as invitation to aphorism, so the answer can also stand apart from the question — and, of course, to generate new questions in turn.

… Does that answer the question?

DP: Yes, that’s a fantastic answer, thank you.

DP: Your poem, “Checklist for a Savior” seems as much a critique of saviors in general as a critique of saviors in a Christian or other religious context. Many of your poems juxtapose spiritual musings with common daily happenings. There are multiple individuals that are likened to Biblical saviors. Regardless of the miraculous tasks included, do you imagine your speaker’s checklist as an appeal to any one savior or is the checklist more symbolic?

BM: Thanks for this question: I do think the intimation of the spiritual within the everyday is part of what I wanted here, throughout the book, not least because I felt a debt to some of the people who recommended me for graduate school: I applied at the same time to MFA programs and to rabbinical school, and had the same recommenders for both, which led to some interesting conversations, to be sure, but also a conviction that to walk through the world in search of a poem is in some ways to search for the numinous. That was one idea, anyway, and somehow I ended up with swans, so go figure.

This poem is not addressed to Jesus, if that’s what you mean, and in my own Jewish context the coming of the Messiah ushers in “ha’olam haba,” which I take to mean “the eternally approaching” (rather than the usual translation, “the world to come”). So in my head, the savior isn’t someone who actually does arrive. To use the terms of your question, then, this isn’t addressed to anyone in particular.

At the same time, I don’t think symbolic is quite right, either, at least in the sense of signs referring to some clearly marked referent. What’s important for me is the stance — the waiting — the speaker, more than the spoken-to. If the poem had only the last two lines, maybe it would work just as well. Or maybe then I wouldn’t be able to say them.

__________

Benjamin Miller has studied at Harvard, Columbia, and the CUNY Graduate Center, and has taught writing at Columbia and Hunter College. His poems have appeared in RHINO, Pleiades, The Greensboro Review, and elsewhere; Without Compass is his first book. For more about Ben, visit majoringinmeta.net.

Dustin Pearson is an MFA candidate at Arizona State University. He received his BA and MA in English Literature from Clemson University. He would eat white rice and soysauce regardless of living on a graduate student budget. He is from Summerville, South Carolina, and would love to direct your literary festival. He can be reached at Dustin.Pearson@asu.edu.

Read

Three Poems by Benjamin Miller

| More InterviewsJoseph D. HaskePaul LisickyMegan StaffelCraig Morgan Teicher |

- Published in Between the Lines, home, Interview, Series

THE CITY by Helwig Brunner, translated by Monika Zobel

Die Stadt zu Linien vereinfacht,

abgeschminkt das eigene Gesicht.

Häuser, Schritte und Gedanken

sind aus demselben Material,

Grafitstaub und Diamanten.

Die Zeit steht, senkt deine Lider,

um einmal jetzt zu sein, inmitten

der schlafenden Welt, hellsichtig

zugewandt den tappenden Fragen

der Somnambulen.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/84459476″ params=”color=ff6600&auto_play=false&show_artwork=false” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Helwig Brunner‘s work has been published in numerous literary magazines and anthologies in Europe and elsewhere, including New European Poets (Graywolf Press, 2008). Brunner has published eight books of poetry, most recently Vorläufige Tage (Leykam Verlag, 2011) and Die Sicht der Dinge: Rätselgedichte (edition keiper, 2012), as well as some novels, short stories, and essays. He has been the recipient of several literary prizes in Austria and Germany.

Back to Table of Contents

The city simplified to lines,

makeup removed from your face.

Houses, footsteps, and thoughts

are made of the same material,

graphite dust and diamonds.

Time stalls, lowers your lids,

to be now for once in the midst of

a sleeping world, clear-sighted

turned toward the groping questions

of the somnambulists.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/84460143″ params=”color=ff6600&auto_play=false&show_artwork=false” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Monika Zobel‘s poems and translations have been published in Redivider, The Cincinnati Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Cream City Review, Mid-American Review, The Adirondack Review, Guernica Magazine, West Branch, Best New Poets 2010, and elsewhere. A senior editor at The California Journal of Poetics and recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship, she currently lives in Vienna, Austria.

- Published in Issue 3, Poetry, Translation