JUNE INTERVIEW WITH STEVEN ESPADA DAWSON

Late to the Search Party is the debut collection of Steven Espada Dawson, exploring the individual and precise depths papered over by common nouns like ‘grief’ and ‘family’. The elegiac collection delves into Dawson’s love and grief for his dying mother, the decades-long absence of his addict brother, and the absence of a father, with language that is clear and resonant as he explores the “gorgeous myth of childhood” and “how to make a family/ from just one man”.

FWR: One of the epigraphs (“A hole is nothing/ but what remains around it”) is a line from Matt Rasmussen’s collection Black Aperture, which focuses on the death of his brother. Late to the Search Party also names and circles around loss, specifically the death of your mother and the disappearance of your brother. In constructing their portraits, the reader also sees you and your loss, your grief, come into focus. This isn’t so much a question as acknowledging its effectiveness! But to turn it into a question: can you speak broadly about the development of the collection? Was the hope in structuring the collection in four parts to have these portraits in conversation?

SED: The two epigraphs that open the book—from Rasmussen’s Black Aperture and Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec—acknowledge the windows I climbed through to make my own book possible. I owe those poems and people so much. They helped shape the emotional landscape of my writing about my family. (Another special shoutout to Diana Khoi Nyugen’s huge and brilliant Ghost Of that was also a pillar of possibility for me.)

As you mention, Rasmussen’s book orbits his brother’s death by suicide. There are not many books about missing addict brothers (or at least I have not found them), but unfortunately there are many books written post suicide. I found myself gravitating a lot to those works because they carry with them a familiar grief and energy. You have these sudden disappearances with often a lot more questions than answers. Diaz’s first book always felt like a family reunion. It’s really a singular, strange feeling to love an addict. It’s easy to hate them and retreat into that certainty. It’s harder to complicate them and hold yourself in their world of uncertainty. Diaz has always showed me how to lean into that. I’m thinking about that quote from James Baldwin: “You think your pain is unique in the history of the world, and then you read.”

During my MFA I was taught to resist writing in fours because its formal stability tends to slow things down, and you’re often looking for modes of propulsion—especially in a longer format, like a book. I arranged the collection into four parts to mirror the elegy series and the title poem, but it’s also to slow things down—something that felt necessary when writing around two family members at the fringe of life and death. I wanted to hold time more carefully.

FWR: I was struck by your return to elegy throughout the collection, specifically the recurrent title of “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Brother’s Heart,” which at times is “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother’s Heart” and “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Heart.” Can you talk a bit about the genesis of those poems? Were they always meant to be in refraction with each other?

SED: I started writing those poems after the shape of a book felt possible, and I needed a throughline to thread the disparate sections, starting with “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother’s Heart,” then my brother’s heart and finally my heart. I resisted writing an elegy series for my father to mirror his absence in my/my speaker’s life, which to me serves to echo his silence.

The heart elegies were originally published as single poems in four sections, similar to the title poem “Late to the Search Party.” I broke them apart after a recommendation from Eloisa Amezcua, one of my first readers. I was always struck by the way José Olivarez separated “A Mexican Dreams of Heaven” in his debut collection Citizen Illegal.

After separating the sections into their individual poems—with a lot of adjustments so that they stood on their own—I immediately felt like the whole thing was a lot more sustaining. For me, a series has a way of acting as a pulse check in a book. I wanted to tell the speaker and the reader “Hey, remember this? Don’t look away from it.” I wanted to capture the discomfort I felt while writing those poems.

FWR: Several of the poems return to your childhood, with a real tenderness, even as “nostalgia rends/ in absence”, as you write in “At the Arcade I Paint Your Footsteps”. How did you balance the (assumed conflicting) emotions as you delved into the past (with the knowledge of hindsight) and the uncertainty of the present?

To expand, I’m thinking of the poem “Lucky”, in which it’s revealed that the speaker’s brother has taken him to the dope house during a time when he’s meant to be babysitting. Despite the awareness of the speaker and narrator to the reality of the situation and the “guardian angel taking work naps/ among hallway sleeping bags”, the emotion I’m left with isn’t anger, but an understanding of the flaws in “someone’s idea of a hero.”

SED: When I first started writing poetry about my family, my experience of nostalgia was often split in two. It’s easier to come to terms with things when you can separate the good from the bad and take them in separately, one at a time like a DMV line. I think that can unintentionally flatten the reality, which is that (for so many of us) happiness threads itself through grief constantly, and vice versa. I think a project of this book is to bring those parts together and make a clearer picture of a more whole, honest reckoning.

I remember when I was young, and my brother asked my mom for $20 to take me to the arcade, then $20 for gas there and back. There was no car. We walked miles to the mall, looked at all the games but didn’t play them, then walked back. I understand that he took advantage of my mom and I. We did not have that money to spare, and he likely threw that cash into his addiction. I also understand that we spent real time together then, and he’d tell me stories about his life and the neighborhood, offer me the brotherly wisdom he thought might help me survive better than he did. Nostalgia can work that way. Insidiousness and sweetness share a bedroom wall.

FWR: There’s lots of touchpoints to nature in these poems, beginning with the first poem, “A River is a Body Running”. A poem like “Orchard”, which has all of this lush imagery used to articulate the growth and ravages of cancer really jumped out at me and reminded me of classical still life paintings, which always include an element of rot (a fly on the fruit, for example). Would you talk about how you brought in those elements of the pastoral?

SED: I grew up in a big city and was never afraid of loud traffic and big attitudes but was always nervous about the idea of a quiet forest, a sudden cliff, vast open water. I currently live on land pinched between two lakes, and it still terrifies me a little bit (see poem: “Lake Mendota, After Sunset”), but I’m getting better through exposure. (Though you will never catch me out on the frozen January lakes like so many of my neighbors.)

When you’re writing a book in places where nature is unavoidable, the flora and fauna and weather start to creep into your work. You’re taught to be a radical noticer, so everything starts to get vacuumed up into the same bucket. Suddenly the human entanglements filling in all the blank spaces become clearer. Heroin lives on the same page as opium poppies because they are fundamentally linked.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview, Poetry, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Tomas Venclova trans. Rimas Uzgiris

Variation on the Theme of Awakening

What echoes in the dark? Is it the wind of June

in the gardens by the lake? If so, the two of us

are in the summer house up high, still young,

having fallen asleep just before dawn.

A muffled engine? Then we’re in that dive

by the harbor, in a country where we’d prefer

not to linger, worn out, not by love, but by the journey

over a wind-swept bay. Or maybe it’s the chirping

of a decrepit, old-fashioned alarm clock

ineptly penetrating the parching air?

If so, then I know I’ve awakened in Tuscany,

but the name of the town escapes me.

The times are in a knot. Impossible to unravel

the nuances of years, places, sounds. A hand

remains, still pressed against my palm, and

a gentle sigh marking the passage of a dream

is more easily understood than one’s voice.

What has melded together will not melt apart.

Our children have grown and left us alone.

So many friends have passed away. Almost everyday,

faces float up from a fog of photographs –

faces we’ll never see again on this earth.

And in the concert hall, flanked by urban maples,

the doors of night are opened by draughts of sound.

The curtain sways. Beyond the window shutters

foliage fades into dim murmuration

while limpid silhouettes climb the walls.

By now it doesn’t matter if this is called

love, or incorrigible fidelity: we share

a fathomless fear, as when the plane

carrying you home is late, or when

bloody traces stain the cotton pad

you try to hide from my sight.

Let’s go to sleep. Let’s imagine we don’t know

that one of us will be the first to go.

Better to vanish, than to be left alone.

An echo once more. Clarifying to a bell.

From a church? A clock-tower? All the same.

From longing, disagreements, pain

a world is born belonging to two

which is shared like a gift

while the unknown beats its wings above.

We were fated to prune grape vines,

to build a roof from Lebanese cedar,

and to burn in undying flame.

It’s almost dawn. As ordered in the Book,

I will not wake you till you please.

I listen to the bell, my breath held tight.

Syllabic Stanzas

Traveller, your life has finally fulfilled your fate.

Above the pine forest, a star rises from its den,

lack-luster and dreamy. The density of towers

closes up the shadowed valley, like you: constructed

from consciousness and nothingness, from flame and from clay,

timeless like a well, a hoary plantain, or a rose.

Some gravel, kicked by your foot, scatters against the wall

where twining alleys and gutter knots spool in circles—

a world that has wasted its worth, a world that once fit

between eroding banks and the bus shelter’s borders:

an expanse of ancient guilts and older limestone where

a poverty of neon freezes the rancid air –

an expanse conjured into a key, rusting in one’s

pocket, into the damp ether’s hum, into suppressed

desire, growing more distant than Saturn, rarely dreamed;

nevertheless, you could walk through that space with your eyes

closed (in the wasteland of day, even better at night),

and you could develop a humane dictionary

from its whimsical winds, from its vineyards of voices,

from the lashing rain and arches of Alumnat Yard.

You only talked about this world. The radar of God

would flash with a confusion of crosses. You were not

able to go astray. To the questioner you might

have answered: “Not on this earth”. You knew bile, treachery,

the unexpected endurance of hopelessness, war

with former friends, grim rows of gravestones, doorways nailed up

diagonally with boards—the cost of returning to

Ithaca. You followed its fall (which you could not hear)

into the abyss of mold. You could easily not

have been, but here you are. The rhythm reborn, breaks down,

the vault splits and crumbles, mirrors crack so that beyond

them you might finally see the place with no glimmer

of hope. Above the stream of time, a blackish leaf drops.

Maybe twenty others already float, each falling

deftly into their essence: reflection and silence.

Bricks have grown rooted and porous, rough to finger’s touch.

The fissure in the wall shines white—becoming a star.

There is just this sandy, rain-pierced, and meandering

range of provincial hills, much like the local baroque

you always see—when you imagine death or heaven.

Tomas Venclova was born in Klaipeda, Lithuania, in 1937, and graduated from Vilnius University. He is a scholar, poet, and translator of literature. Venclova was a founding member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, which monitored Soviet violations of human rights. Threatened with sanctions, he emigrated in 1977. He received a PhD from Yale University in 1985. Collections of his poems have been published in English as Winter Dialogue (Northwestern University Press: 1999), and The Junction: Selected Poems (Bloodaxe Books: 2008). A new selected poems in English is planned for 2024 with Bloodaxe. Venclova has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Lithuanian National Prize in 2000, the Yotvingian Prize in 2005, the Poetry Spring Mairionis Prize in 2017, and the 2002 Prize of Two Nations, which he received jointly with Czeslaw Milosz. He is professor emeritus at Yale University, and now lives full time in Vilnius.

Photo Credit: Ivan Milovidov

- Published in Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Zuleyha Ozturk Lasky

Severn, Maryland

pink mouths of crepe myrtle mouthing words like çay demle kızım and a sloped garden in the back and a creaking deck and a bookshelf full of religious texts and my bedroom in robin blue and hairbands always lost under couch cushions and prayer rug facing the direction it’s supposed to face and me facing the opposite way and prayer rugs quartered and stacked in a pile inside the tv console and prayer beads hanging from lamps and Keurig machine and milk frother and two teapots (one electric, one traditional) and windows facing trees and grape leaves brined in jars and fig jams lined on the shelf and sink full of dishes and when washing dishes a window facing the neighbors pool and my father asleep and overworked on the couch and a bowl of seasonal fruit and my mother asleep and overworked on the couch and my sisters whisper laughing and pantry full of turkish sweets and sunflower seeds and gallon of olive oil and lentils and dried mint and fridge that always hums past midnight and tv tuned to politics or a movie and fly always buzzing and a trail of ants that will never leave

Hyattsville, Maryland

a teapot recently bought from turkish market and sunlight slipping through slats like ballet dancers and three lemon sprouts and a balcony to count the balcony dogs and the sunflowers painted on a ceramic plant pot and next door neighbors with their balcony door open and my first ramadan away from family and our neighbors wake up with us during a salted night and ezan waltzing out their door and dust on our bookshelves and your phone in pool and our studio with high ceilings and built-in granite desk which is technically a bar corner and Beatles poster with fox-gloves that become jellyfish when dropping acid and so much time to graze on your lips and quarantine thanksgiving and quarantine work and quarantine writing and quarantine walks and masks forgotten in pockets clung to dryer sheets and sick three days after vaccine and sick three days after wedding and impromptu Ocean City trip where we ran under kites shaped like our laughter and so many matchbox apartments with high ceilings in gentrified neighborhood and mid-day walks to Vigilante to order americano and latte and somedays there were two or three walks just because and no one on the streets and walks near the railroad tracks and the apartment our home now with our fortune read in coffee grinds shaped like fish and look how they feel swimming under our feet

- Published in ISSUE 27, Poetry, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Sarah Audsley

Sarah Audsley is a Korean American poet from rural Vermont. A graduate of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College, her debut book of poetry Landlock X (Texas Review Press, 2023) explores the intricacies of being an adoptee not only through the textures of language but also visual arts crafts, such as collage. Deeply pastoral, and with the sense of the handmade, her poems aim to unstitch ideas of identity and what it means to be American today.

FWR: I’d like to begin by asking if you could talk about the use of the x symbol in your poems. Throughout the book it’s used to stand for an unknown variable, but also signals the X chromosome, multiplication, reincarnation, and erasure and absence, as well as the speaker herself. Can you tell me a little about where you got this idea from, and how it developed throughout the process of writing the book?

Sarah Audsley: Yes, the symbol “X” is doing a lot of work in the book. The manuscript went through several revisions and through that process I realized I needed (and wanted) a thread that connected the poems across the three sections. The concept of being a landlocked person, someone who is separated from and not touching water, or, in the case of the adoptee, separated from their origins, came to me and then it all clicked into place. The “X”, as you mentioned, is many things, but I also wanted to consider all the variables that make up a life, in particular, all the (un)known variables (and therefore consequences) of adoption. In the revision process, I was guided by two of the earliest poems in the collection: ‘When My Mother Returns as X” and ‘Origins & Forms: Eight Sijos.’ I think it’s remarkable how the writer can only see the breadcrumbs she’s already written for herself after some distance and perspective. So, all I can really say is that I followed the trail I’d left for myself.

FWR: Mathematics in general is also a recurring motif in the book, especially in the poems ‘Origins & Forms: Eight Sijos’ and ‘Continuum’. Can you tell me more about your interest in math?

Sarah Audsley: Mathematics does recur throughout the collection, which I think is spurred on, partly, by the symbol “X.” Honestly, I am pretty horrible at math, which may be why, in poems, I’m interested in the field of study purely from a theoretical standpoint. I am also thinking about how the speaker of the poems is one adoptee among so many. Numbers are only able to tell one kind of narrative. How do we calculate our decision making? How do we face the totality of so many relinquished and exported children? The last sentence– “I am all those mathematical distances”–in ‘Origins & Forms: Eight Sijos” somehow, in the context of the adoptee narrative, makes sense to me. Finally, I think the subconscious and the poet’s obsessions with certain ideas, is how themes like mathematics recur; it’s really not an overtly conscious process.

FWR: I loved how many of your poems incorporated the color yellow – as a woman of color I love writing about color! – but in particular I loved how you reclaimed the color from its racial connotations, such as in the poems ‘It Was a Yellow Light’ and ‘Broken Palette :: a retrospective in panels’. Could you talk more about your intentions around this?

Sarah Audsley: Yes, the color yellow is featured prominently in the collection and becomes one of the important threads throughout. “Crown of Yellow”, a poem early in the collection, was an important poem and began my exploration of the color yellow. I leaned into exploring the ways the color yellow recurred in my memory bank. I also did some research on its historical use and picked up art books on color theory. I am glad the reclamation of the color yellow resonated with you. As an Asian American, it is an important color to consider. I wanted to explore “yellow” not just in a racial context (which is so important), but also in art and culture, and to also mine my own memories and associations with the color.

FWR: You’re also a self-described rural poet. How would you say place and/or the pastoral influence your writing?

Sarah Audsley: “The rural poet” seems like it is in contention with “the city poet.” For me, maybe it is! Because, for me, place and my connection to place is essential. I enjoy visiting cities and being an interloper in city life, but I will always choose to live in a rural place. Walking my dog three times a day, cross country skiing in the winter, and hiking in the mountains in the summer, offsets all the daily computer grind. I like to think, too, that it feeds the work. To put it in another way, I’m a better poet if I’ve spent some time outside noticing and moving in the woods. The natural world offers me a sense of belonging. So, of course, this will appear in the poems. As for the pastoral poetry tradition, two poets and influences come to mind: Vievee Francis and the “anti-pastoral” poems in Forest Primeval, and Jennifer Chang’s Bread Loaf Lecture, “Other Pastorals: Writing Race and Place” (June 2019, available here.)

FWR: One of the major threads throughout the collection is the narrative of the speaker as a Korean American adoptee in search of her birth family. The quietly devastating ‘On Meeting My Biological Father’ is contrasted with poems on the possibility of meeting a half-sister, and meditations on the speaker’s deceased birth mother. While the process of searching for a birth family as an adoptee must understandably be a difficult and complex one, the book ends on a positive note with the speaker contemplating her mother’s reincarnation. What was the process of writing these poems like for you and where do you sit now with your relationship to your birth family?

Sarah Audsley: I am grateful for the opportunity to write and to think deeply about adoption (my own) and how it is situated within the larger adoption industrial complex. My relationship to adoption, and my birth family, and the term ‘family,’ in general, is not fixed in any way. Instead, I think it will continue to evolve and change over time. Landlock X is just one attempt at grappling with it all. I hope the collection adds to the ongoing conversation around adoption, and I’m pleased to offer it as one more voice contributing to adoptee poetics. (Check out The Starlings Collective.)

FWR: It’s clear that visual arts is a large part of your practice, as the book is scattered with many photos and documents in English and Korean associated with your adoption process, such as the average measurements for Korean children, or advice on creating cross stitches to ‘celebrate your Korean American culture.’ In response you’ve altered these texts with additional text or drawings or photos to create a kind of documentary collage. Can you talk a bit about how art inspires your poetry and your process around it? Are there any multidisciplinary artists in particular who inspired you?

Sarah Audsley: The visual components in Landlock X are important to the overall conception of the project, but they came later in the manuscript’s evolution. (I very much feel like I dabble in the visual arts and have not achieved any sort of mastery in that field.) As I was revising the manuscript, I turned towards collage, which makes sense to me as a way to access and interrogate texts through visual elements. The visual components (visopo or visual poetry) provided a way to examine and interrogate my adoption records in a new way that the traditional lyric and narrative poems could not. (Sometimes we just don’t have the words. Sometimes the image functions louder than the words. Then, the combination of the two creates a new alchemy. Here, I am still experimenting, and that feels freeing.)

In many ways, these files and records of my adoption are one form of my inheritance. I think of the collages as a transformation and reclamation of that inheritance. My parents diligently kept an archive of my adoption records and associated paperwork in file folders in a filing cabinet in the basement of our house. Working with them was a natural evolution in the writing process. The collages in Landlock X complete the overall vision for the book, and I’m grateful that Texas Review Press included them. Some influences and books that inspire me (some for their inventive use of text and image): Cleave by Tiana Nobile, Hour of the Ox by Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, Ghost of by Diana Khoi Nguyen, Litany for the Long Moment by Mary-Kim Arnold, Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung, Olio by Tyehimba Jess, and many more. (One more thing: adoption records are not always reliable or accessible, and in some cases they do not exist at all.)

FWR: One of the biggest nods you give to your love of ekphrasis is the structure of the book, which is divided into three sections — one for each of the words of the ekphrastic poem ‘Field Dress Portal,’ which you wrote in response to a friend’s painting. Can you tell me more about this collaboration and why you chose to structure the book this way?

Sarah Audsley: ‘Field Dress Portal’ is an important poem for me. Structurally, I wanted the collection to hinge on that poem, which is why it appears about half-way. ‘Field’ represents all the nature elements and the interrogation of the pastoral mode that recurs throughout. ‘Dress’ represents performative actions, costumes, exteriors, looking at something at face value, etc. ‘Portal’ represents transformation, metaphor, moving beyond this reality into another…So, these section titles provided structure and also each carried, in my mind, their own meanings. They also function like a triptych, which I really like, and they also helped me sequence the manuscript and to place the three erasures.

The poem uses the painting ‘Field Dress’ by Lauren Woods as a jumping off point. I watched the painting change over time as the painter posted images on social media and I was enamored. We’ve never met. We’ve only exchanged a few notes here and there when the poem was published in the New England Review. The ekphrasis mode feels challenging. It also makes sense to me as a way to engage with art, and to practice seeing and describing. It is another way to connect beyond the self. However, what fascinates me is how the selective process of describing actually reveals something of the speaker’s inner workings, their perceptions. In this way, ekphrasis as litmus test, is another way into the mind of the speaker of the poem, and, also, into the mind and heart of the poet.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

YOU BLACK BALD CHICKEN by MARS.

Or a rebuttal to KM playing the Dozens

hair slicked in let’s jam & pulled into ponytail

flesh soaked in sun even in winter’s frozen stare

you shadow of a body

All we see is your teeth when you smile

you backdrop to everyone’s flashy gold wrist

you glistening black

blackity black black

turn to the brightest light of you

and see more black

black turned over and still black

hair so coarse they can’t miss the black

your black so absent they say you a peculiar ghost

ancestors laughing at your blackity black ass

How you so black you disappear black

did you wish your black was the palm side of your hand black

a black worth looking at twice black

you born after the my black is beautiful blacks

black born in the year of erasing blacks

black like the forest get black

black like a black that welcomes a star’s gentle glare

black and more black

You ever see a black so black black

- Published in Featured Poetry, Poetry, Uncategorized

ART by Anna Beth Lee

“Traffic Jam”

“Pool Table”

Anna Beth Lee is a rising sophomore at Drew University. “When creating, I ask myself: How can I make people think when they view my art? How can my art be like a fun guessing game? How can I bring that “A-ha!” feeling to viewers when they figure out the wordplay in my art?

“During a trialing school year of uncertainty, I sought to find the joy and humor in everyday objects. Using Homophones, I investigated creative ways to depict two words that sound the same, but have different meanings. This whimsical approach allowed me to shift the way that I view the world: There are endless connections that can be made between concepts and objects, and finding similarities and patterns in life cause one to realize that aspects of our world are more relatable than we may think.”

Here is a link to her online portfolio, which features her photography, dancing, and drawing: https://annaelizabethleetn.wixsite.com/myportfolio

- Published in Issue 23, Uncategorized

GATE by Grayson Wolf

Before I’m born, I’m in no hurry to be born. So I arrive

unhurried. A shape in the trees. Weighted, a fishing-line pinching

the water’s surface. A voice like the moon, wordless

but listening. I grow gold, then, slick as a raindrop, red

as a hen in a doorway rent by daylight. I arrive early. I arrive

laughing—an inside joke—a belly-laugh

inside my mother’s belly, laughing

and laughing.

A dog disappearing into a snow-pile, an elephant

discovering the ocean. I come to full-grown

with a child’s body, asking: who are you to tell me I’m not a bird?

I look (so they say) the way any baby looks.

The way my grandfather, quiet as a lamppost, looks

five floors down from the hospital window

moments before I’m born and just in time to witness

his blue Toyota stolen and slipping up 7th street.

Like a train to its uncoupled caboose, I’m born

no good at math but here’s Buster Keaton’s sad eyes

as his hat drifts down the Seine. I’m the hat

the train the caboose.

The coal going in the smoke coming out.

I’m lifting the ties behind me, running ahead and laying them down

different. A mill raising the river up in pieces until the same old

same old, electrifies the village. I lean

-in, hunch-over, a jockey at the start-gate.

Horse-tremble. Ear-strain. Like a hammer

coming down on a nail—Bang! I’m out

and into the hands of strangers, gamblers, horse-thieves. (You know,

“family.”) They lift and look me over. I look

at them, they look at me (it seems

like the thing to do). When they untie me

from the mother I was, I arrive asymmetrical and out

of sync. Odd as an em-dash

in the river of things. Like rain. A sudden breeze. Like blood

dappling the clear-veined light of an IV. When I wake

I wake as a building wakes, one

window at a time into the unfinished evening. I wake

as my grandfather does, partway

through the night, newly widowed, reciting

to no one but the ceiling: ‘I went to school,

I got a job, I met my wife…

‘I went … I got … I met …’

I come to in the middle of a shift and thinking

only of sleep, work the whole way through.

- Published in Issue 22, Uncategorized

DON’T CALL ME YOUR PRINCESS by Megan Culhane Galbraith

Once upon a time, there was a young girl who lost her mother too soon.

Cinderella’s grief was bottomless. Every day she visited her mother’s grave.

“Where is my great love?” she asked.

One day her mother answered.

“Cinder, dear, your great love is inside you. You must be yourself, for it is only then that your great love can find you. They may dress you in rags, you may clean a fireplace, but you are exquisite. Look deeper, honey. Let the love radiate from within. Be yourself.”

Cinder’s home life was messy. Her father had remarried and her stepmonster hated her.

Cinder did the dirty work and kept her head down.

Her stepsisters hadn’t gotten laid in a while, and they were extra mean about it.

As she cleaned ashes day after day, her mother’s advice clawed at her. “Love yourself first.”

“But how, Mother?” she asked.

Just then, a flaming ember burned her hand and a white-hot heat lit up within her. She remembered the bedtime tale of the phoenix her mother used to tell her.

She rose from the hearth and gave herself a smoky-eye by slathering the dark ash on her eyelids.

Cinder heard of a fancy dance in town, but she hadn’t been invited.

She was tired of waiting to be asked. Meanwhile, her horrible stepsisters paraded their sexuality like marriage was an endgame.

“Fuck this,” she said, and she decided to crash the Prince’s Ball.

Her friends Pinky and Bluey helped her get ready.

Cinder had the best time at the Prince’s Ball by herself. She adorned her hair with peonies plucked from the centerpieces. She slurped oysters, wiped her chin with the back of her hand, and burped. She requested the chamber orchestra play “Free Bird,” then twirled and laughed and danced like no one was watching.

But her stepsisters were watching. They were wicked jealous that all eyes were on Cinder.

And the Prince was watching, because, you know, the male gaze.

She’d admit later to her girlfriends that the Prince was great in bed, but he sold vapid promises and empty charms to all the other girls. He had a wandering eye. She’d seen the texts to his ex.

Cinder wasn’t buying any of it.

“Don’t call me your Princess,” she said.

She went where her desire led. She was safe, not sorry, because girls just wanna have fun, too.

So, she ignored the Prince’s lame texts, tested negative for the STD he said he didn’t have, and bought herself a vibrator.

She did what she pleased. She loved who she loved. Fuck the patriarchy.

Best of all, she finally came first.

And she lived happily ever after.

- Published in Issue 21, Uncategorized

COME CORRECT by Erika Meitner & Traci Brimhall

If my lips are zipped—if I keep our delicious and contagious secret

—if I am amnesiac or too hungover to remember your mouth

on mine—if I forget the imprint of your body indelibly stamped—

if I search for you, call for you, lover, stranger, alien—if I offer up

gratitude to the air—if I rob you of your signals and energy (are you

battery-powered?)—if we fuck again and again all scorching night—

if we lock our power up to prevent a meltdown—if we twine ourselves

together like an interrobang—if we cross the imperial sea holding hands

or recycle our bodies into danger zones—if we do not yield—if I let you

come deep inside me (finally)—if we buy more time—if your body is a

snow-covered mountain—if your body is an emergency—if you sing

Karaoke (I will Survive? The Boxer?) under the stage lights at Tokyo Rose—

if our bodies become facsimiles or ghosts of themselves, like melted

snow or animal tracks—if you leave me—I need to say this, so listen:

if you go, do it quickly—the way a rabbit darts into the brush

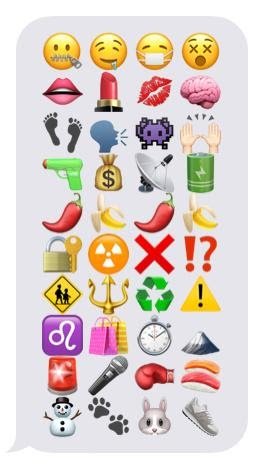

emoji poem by Traci Brimhall / ‘translation’ by Erika Meitner

- Published in Issue 21, Uncategorized

THE HOUR OF THE WOLF by David Roderick

Often one of my daughters

howls me to her bed,

and like a trained victim I trance

to their denned room

to comfort a face

shaped by some dream

or another—eyes pressed shut,

lips in the nightlight

the shade of a dried peach.

Isn’t it absurd,

an old prince like me,

stirred by their delicate mouths?

I nuzzle my head into hints

of urine and Vick’s.

Then, too awake

inside the ticking, I gnaw away

at the latest tragedy

from Florida or Mosul

or simply dwell on

the wrecked condition of my kind—

wondering what I can do

about the rapidity

of my daughters’ heartbeats

and my own human

rapaciousness over their lives.

- Published in Issue 21, Uncategorized

ALL SAID & DONE by C.S. Carrier

I propose an elegy

the shape of

a cairn for my father.

with 63 wooden objects,

one for each year of his life

One object is the cube.

Some cubes made by laminating wood

with paper, fabric, tool dip,

tobacco leaves, eagle feathers.

Another object is the box.

Some boxes made into bird houses,

filled with neon fishing line.

White cotton bolls.

Some boxes made of twigs,

filled with broken bottles, shotgun shells.

Some as shadowboxes stuffed with

charcoal, shredded newspaper,

cigarettes. Random bones, maybe.

Most objects have language

on them via

carving, writing, painting, etching,

embroidering, burning, incense, spell.

Some have language on paper

floating on their surfaces.

The elegy is anchored by a heart,

a lump of stoneware

spiked with 63 nails,

that bubbles with red glaze

& rests on a shallow bed of ash.

- Published in Issue 20, Uncategorized

BATAAN DEATH MARCH AS TAROT CARD: NINUNO NG RATTAN by Hari Alluri

After Jana Lynne Umipig

Capitulo lullabye. I dreamscape mesmerized

by ruination sky. Inordinate and restful like

forgetfulness.

At wreck.

Catch me in the morning

and I fleck. As in, as shock,

the intro only

masquerades: we’re in the middle since. At play, at effervesce

glow-tide my destination, journey hurts my name:

don’t be questing me, don’t labyrinth my style. I pathway

like gamayan, macadamia frog-leg in a rice paddy with lime. In agarbathi

smoke—I float. Kalabaw-

English when I shop. Chop

because I’m hungry, chop chop like

the rendezvous’s the pathway and the crossroads

what you smuggle. I put this on your blood,

dapple skulls with ancestry and chime. Straggle, grandchild,

if you want to live.

- Published in Issue 20, Uncategorized