ASHES by Nandita Naik

The river Ganga seethes with ashes. We shove our elbows into each other’s sides, muscle our way in to look. The bodies of our grandmothers and grandfathers burn on the cremation ghats. We watch them become less like bodies and more like a collection of burning fabric and bone marrow and veins turning into ash.

We collect the ashes into the kalash, and then we say a quick prayer and leave the kalash with the purohit. We wonder if the ashes carry the sickness inside them, or if the sickness has separated from their bodies, and in that moment, we imagine the sickness itself as a body, vulnerable and tender. After a few days, the purohit hurls the ashes in.

The ashes dissolve into the river, mixing, impossible to separate again. This makes it harder for us. We cannot point to a congealed lump of ashes and say, Here is Patti who cooked the best idlis in the world and here is Ushana who made all those beautiful paintings and here is Smruti who is a very fast runner and beat all of us in the one hundred meter dash and here is Pooja who hated us, maybe, and here is our uncle Jaya who, when we told him we were going to be famous singers one day, laughed so hard his fingernails fell off. We still keep the fingernails in tiny urns on our desks.

All these people and no way to tell them apart. We know their names, but the river doesn’t.

*

When we are sick, we come to the river Ganga begging it to heal us. The heat pares us down, reduces us to thirst and burning. Some of us bring wounded limbs or injuries, inherited through our bloodline or self-induced by our stupidity. Others bring the sickness, arms spangled with mosquito bites.

The smell of scorched hair hovers over Varanasi. The clang of bells. Merchants hawking remedies too expensive for us to buy. Orange embers from the ghats land in our hair and remind us how close we are to burning.

Our proximity to dead bodies makes us nervous. But despite this, the Ganga is a healing river, and there is nothing we need more than to be healed. We anoint our foreheads with ceremonial white ash and bathe in the river. The ashes seep from our hairlines and pool in our collarbones.

Nalini breaks off from us and runs to the river bend. She stoops to cup a section of the river in her hands and her great grandfather passes through her fingers.

There are so many memories we steal from Varanasi. The sweet dahi vada we gnaw between our teeth. People asking for money so their families can cremate them when they are dead. A woman crying as the sunlight strikes her face, sculpting her into something raw. Ashes fall into the river and the water reaches up to touch them.

In the years following the sickness, we learn who the river has chosen to save and who it has forsaken. Swati dies. None of us knew her very well, but we knew she mostly liked to eat food that was colored white. So, we burn white food along with her.

We are scared to scatter her ashes into the river. What if the ashes are still Swati? What if she is still lodged in them, unable to get out?

Kavya tells the rest of us we are wasting time, so we throw Swati into the river anyway. Her ashes mingle with everyone who came before us and everyone who will come after us. Swati’s white food mixing with Pooja’s maybe-hatred mixing with Patti’s love mixing with Smruti’s mile time mixing with Jaya’s laughter.

*

Nalini looks for animals in the Ganges. The softshell turtle, the river dolphin, the otter. But they will not come near the crush of visitors. We don’t tell Nalini this, so we can watch her try and fail to find them.

She mistakes a passing boat for the back of a dolphin and jumps into the river. We laugh at all of her pouring forward. Nalini struggles and screams, thrashing in the water.

There is a moment where no one knows what to do. Do we jump in and risk ourselves? The boat’s propeller could pull us under, add us to the tally of ghosts in this river. Or do we let her go?

Then Kavya jumps in, swimming towards Nalini, and it would look bad if we didn’t jump in, too. So we all swim to her and pull Nalini to the shore. The boat misses us by a few feet.

Exhilarated by the rush of almost dying, we make promises we can’t keep. We tell each other: we’ll do anything for you, we’ll die for you, we’ll bail you out of jail, we’ll donate our kidneys if you ever need one, just tell us what you need.

We know we’re being stupid, but it’s okay to be stupid. We think we have time.

*

But we grow up, finish school, get married. For some of us, our husbands die, and we break our bangles, don the white clothes of widows, and migrate to settlements.

For others, we are frustrated because either our husbands won’t die, or our future children won’t be born, and nothing seems to change.

We move away from Varanasi. The population of river dolphins dries up. Gharials are endangered. We read about bombings and shootings and stabbings in the paper, and pour tea for ourselves to drink in the afternoon.

It is only sometimes when the sunlight glints scarlet against the waves or our bodies flush with desire or we touch the fuzzy heads of our children that we think: we are lucky to be alive. Lucky to not be particles in the river right now. Who would ever want to leave?

*

Nalini is run over by a rickshaw two blocks away from where we live. When she calls out for help, only the rickshaw driver hears her, and he doesn’t stop. She bleeds to death in the street. Her kidneys are ruined.

Nalini’s family does not have enough money to do a full funeral ceremony, but they do everything else right: pray over the body, cremate her, scatter her remains at the sangam where the three rivers meet. Sacrifice a husked coconut, milk, some rice, a garland of flowers.

After her death, the body that used to be Nalini exists amongst the softshell turtles and river otters and endangered gharials.

In some years our bodies will be ashes, and our children will celebrate our lives. They will feast on banana leaves and set our pictures on our verandas and eventually they will cremate us and throw us into the river.

We hope they will cry for us, at least a little. We want our families to grieve for the hundreds of generations that will forget us after we are gone. We hope their tears mix with our ashes, all of it ending up in the river.

*

When diseases and motorcycle accidents and electrocution finally shove us out of our bodies, we roam the earth for forty days. We can’t believe it is over. We want to haunt the people who killed us or the people who loved us, to terrify them equally, to make them realize we are still here.

But our families scatter our ashes in the river so we cannot return to what is left of us. Some of us grow vengeful. Our families aren’t grieving enough. Others want to save our children from a forest fire or to console our husbands or simply to die again, but with more sophistication.

When the hunt for our ashes exhausts us, we recall the feeling of the cool river against our face, on that day we almost drowned with Nalini. We return to the river. Pollution has darkened the waters. We sift through the water, but we can’t find any trace of our old bodies. Everything that we were is gone, dissolved, so we sink to the riverbed and surrender to a glacial quiet.

*

We are born two weeks early, seven weeks late, in rickshaws, during stormy nights, in the sunlight, in a horse stable, on the terrace of an apartment building.

Our parents take us to the river Ganga to name us. Around us, the night eddies and aches with the sound of language we cannot yet untangle. We drink in everything with our newborn eyes and immediately forget all of it. The ice-cold water rushes towards our faces. Our eyes sting with the salty water. We scream and thrash to get away from it. But we cannot escape.

We want the water to leave our eyes, but our parents lift us and dunk us again in the river. We make underwater sounds but they come out as bubbles, so we watch our voices lift up and up until they break against the river’s surface.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Fiction, home, Monthly

Rajiv Mohabir: FROM “SWAGGERMAN, FLYMOUTH” A DEVIANT TRANSLATION

Introduction by Rajiv Mohabir:

The poems that follow are from a forthcoming manuscript. These poems are a type of translation of a Caribbean chutney song called “Na Manu” by the Surnamese singer Bidjwanti Chaitoe Rekhan in the early 1960s.

The song “Na Manoo Na Manoo Re” from the 1961 Bollywood film Gunga Jamuna in which Lata Mangeshkar sings a song of similar lyrics may have been an inspiration to the Sarnami Hindustani song of Bidjwanti Chaitoe Rekhan.

Still, adding more layers and complications, is this song, remade by Babla and Kanchan– a duo from India who took Caribbean songs and remade them for worldwide distribution in the 1980s– that was very popular in my family and the community of Guyanese and Caribbean Indians that we interreacted with in Orlando, New York City, and Toronto, so my move to translate them is one that is intimate given my own linguistic history of erasure and reclamation. This is the version that I grew up dancing to, knowing it intimately in the twisting of my body in feral dance.

What is remarkable about each remake and each rebranding is the change in lyrics and instrumentation, translated each time to fit the contexts of the viewers/singers/dancers/audience. To start with the Surinamese version, the regularization in Rekhan’s lyrics allows for a predictable structure that is easily replicable, though it maintains the play and irony of the original. I keep the play and irony of the original in mind as I work through the various pieces in this section of the translation process I am presenting here.

The process that I use to translate this song I’m calling “deviant:” these are deviant translations. I want to destabilize language and the ideas around final realization and “arrival”, in order to resist stasis and provide space for all of the queer slippages of language and their worldviews in their very particular speech communities. When I was younger these songs in Hindustani would be translated into a Creole iteration with a different poetic orientation. The English interpretations were up to me. All of the poems are retranslations of retranslations of retranslations in and out of Guyanese Hindustani, Guyanese Creole, and English. In this way I envision each incarnation as a possible emanation from the text as even the idea of primacy and the original are dubious. I approach each iteration with a different idea of what I want to communicate: what affective dimension is available in the language that has similar resonances throughout while not always being literal. What are the affective hauntings of these lyrics, languages, and musics? This is the central question driving my experiment.

I’m also obsessed with Creole and Bhojpuri indeterminacies in English and the ways these languages use grief, humor, and joy in differing ways. Using Guyanese Bhojpuri, English, and Guyanese Creole, the deviant translation is nonbinary and ever migrating. (In live performances of these songs, performers sing as the spirit moves them with lexical fluidity an incarnation of their own creative magic). What results are translations that are not translations as such in that there is no resting place but rather motion with the deviant driving the multiple crossings.

From “Swaggerman, Fly-mouth” A Deviant Translation

Swaggerman, fly-mouth

what is true?

I take in the raven moon’s glow

so when you deny me

I’m still opalescent.

Why veil this shine

for a liar’s night, a mind

wipe serum?

My churas are not shackles—

It’s morning and I’m gilded.

*

Things Not to Forget in the Morning (Liar Though You Be)

moonlight moonlit night full moon light

my veil with kinaras of gold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

my silver bera

*

a song from laborer to recruiter is that why it is so sonorous and resonantly all these years later summoning the ghosts of tide and bond how even as the language receded from us like a tide coolies couldn’t release still can’t let fly this story or rather it possessed us in the dance halls as soca chutney a music salve for the pain of forgetting for getting into the boats and we are haunted by the memory of a promise of return but it wasn’t about the physical return but a return to wholeness-as-India that our masters and owners reneged on denying generations any passage not rum-doused and sun-scorched is this why we dance so fiercely in the moonlight is this

*

What part of me is memory?

The skin and muscle,

neuron and fat—?

Don’t believe in god.

It’s a mean lie to lay you down

to strip you of cloth and gem.

You are not headed any place

but into the ocean as cremains

and pearls of bones

not quite machine smashed.

Did you forget? Is it beautiful

this morning where you think you are?

*

चूड़ा बीढा काढ़ा

काँगन बाँगल जिंगल

चान्दी की चान्दनी जइसन

दुपट्टा चुनरी ओढ़नी

निक़ाब परदा रूमाल

बदन की बदनिया जइसन

*

Look. Wha’ me know me go tell yuh

De man come

an’ tief all me ting dem

‘E come cana me

an’ talk suh lie-lie talk

an’ me been haunted

fe lie dung

whe’ ‘e put de ordhni

But wha’ matti hable see a night?

Come daylight

dopahariya

‘e na remembah

me na me bangle,

how de moon a shine,

O gas—

how de moon been a shine

*

Sugar floss melts in dew

forgets its thread’s any spun yarn

So what thing is moonlight

who deposits amnesia

for even a woven veil

to dissolve from your memory

despite my ornaments

exquisite and golden forged

all lost in the ephemeral jewels

globes of hundreds of tiny suns

bending grass leaves

into pranam which is both

greeting and leave taking

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

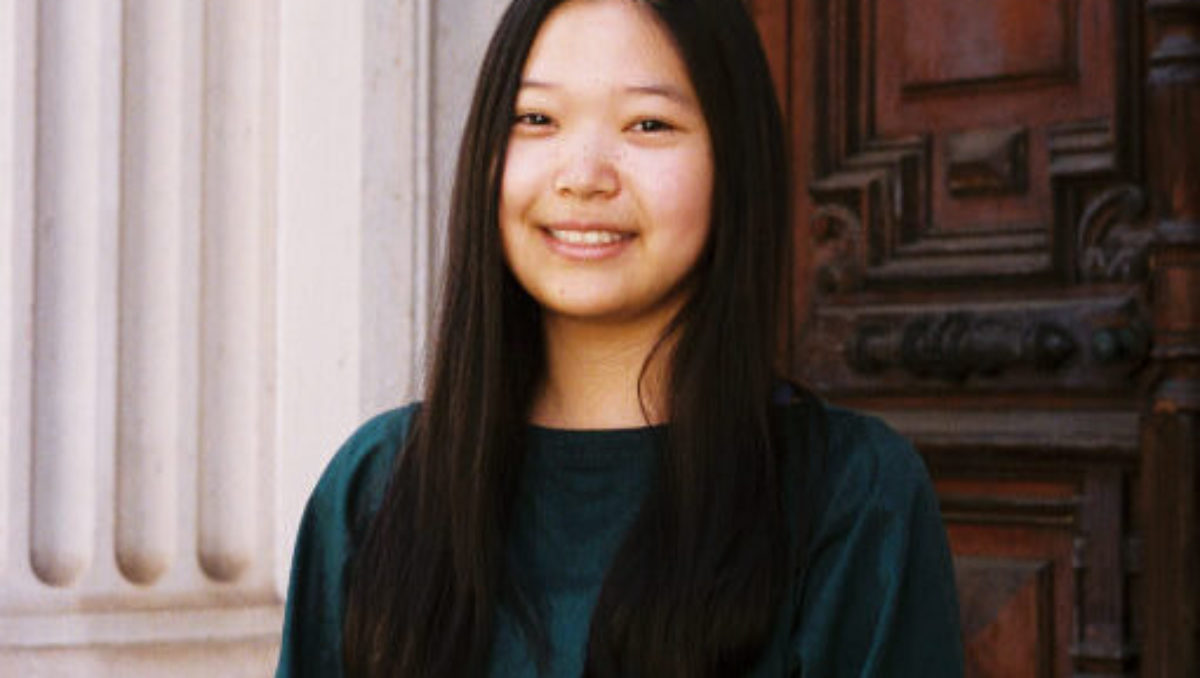

INTERVIEW WITH K-Ming Chang

I first read K-Ming Chang’s writing in 2018, back when I was Fiction Editor of Nashville Review. Her story, “Meals for Mourners/兄弟”, captured my attention with its embodied, elemental language and stirring portrait of family life. Since that time, Chang has written a novel, a chapbook, and a story collection, among other projects. Currently, she is a Kundiman fellow. Her story, “Excerpt from the History of Literacy”, was published by Four Way Review in November 2020. While Chang’s characters bite, use meat grinders as weapons, and store their toes in a tin, Chang herself is generous of spirit, prone to doling out affirmations. During an unseasonably warm day in early spring, we talked about the craft of writing, giant snails, and the magic of making things possible.

-Elena Britos

FWR: Today I thought we could talk about your writing through a craft lens. Craft means different things to different people. To start, writer Matthew Salesses says in his recent book, Craft in the Real World, that “Craft is a set of expectations. Expectations are not universal; they are standardized. But expectations are not a bad thing.” What expectations do you feel you must meet in your writing, and whose expectations are they?

(Chang holds up her own copy of the book excitedly)

KMC: Maybe this is more what expectations I don’t meet, but I never want to explain things [to the reader] I wouldn’t explain to myself. If I were the reader and I wouldn’t need an explanation, then [as the writer,] I’m not giving one, even when I know it could make the reading more difficult for someone else. I write for myself first and foremost. I always use myself as a compass. If I am surprised or delighted by something or laugh at something or understand something, I allow that to be the compass. If I think too much about how a stranger will read it, I lose all sense of how I want the work to be.

FWR: So you’re meeting your own expectations when you write?

KMC: Yes. My expectations for myself are harsh, and I can be self-deprecating toward my own work. So, what I try to do is distance myself from [my work] as much as possible. I try not to think about how this is something I’ve spent a lot of time on and hate. I try to give myself time, a couple months or longer, and come back to the page to experience it as a reader. I look for a sense of surprise, always. I want to think, “Wait, I don’t remember writing this! I didn’t expect it to end there!” If I am not surprised, I know it’s not ready yet.

If I am not surprised, I know it’s not ready yet

FWR: How do you shock yourself when you are the one creating the surprise?

KMC: It does happen! When it goes well, the work ends up really far from where I started. It’s like a game of telephone from the first sentence—it mutates so much. Sometimes the surprise is even just a metaphor, and that can be enough.

FWR: Right now, you edit The Offing’s Micro section, which the journal files under its Cross Genre vertical. When I think of your writing as a body, “cross genre” is kind of the perfect category-defying category for it. It’s like having a non-container. Yet, no matter what form your writing takes, I feel I would recognize a K-Ming Chang piece anywhere. Part of the reason for this is your use of language on a line level. How would you describe your style?

KMC: I love this idea of a non-container! I think my style is very language driven, the idea of letting language lead me rather than logic. This sometimes results in a lot of derailing in my work—like, wow that sounded really interesting, but what does it mean? I find that’s where I have to reign myself in. I am very interested in lineages and mythmaking, creation and destruction, the elemental things that are common in mythical worlds. My style is hard for me to describe because I feel I am always trying to break out of my own style. When I write poetry, I am always trying to break out of my own poetic voice, and when I write prose, I feel very resistant to prose forms and sentences. So, it’s a constant wrestling.

I think my style is very language driven, the idea of letting language lead me rather than logic

FWR: I am always amazed by your ability to work fluidly across genres and forms. You write poetry, short stories, novels, micro fiction, and beyond. You have a poetry chapbook coming out from Bull City Press called Bone House. You also have a forthcoming story collection from One World called Gods of Want. When you sit down to write, do you have the intention to create, say, a short story from the outset? Or do you first have an idea for what your narrative is about, and then select its formal (non-)container?

KMC: I used to think it was a profound process, but it’s really like having a loose thread on your sweater that you yank. Usually, I start with a first sentence or even a few words. And then I pull on it and pull on it and let it expand. Usually what ends up happening is that whatever I think I am writing ends up as a giant block of text. When I think about what kind of narrative it will become—if it is a narrative—that is part of the revision process. When I am in the process of writing and producing, I really have no concept of “is this fiction, is this autobiographical, is this an essay, is this a poem?” That’s a lens for later.

FWR: That shows in your work. It feels like the language almost comes first and then the story blooms in this really interesting, organic way. What was it like writing Bestiary using this process?

KMC: I always joke that I tricked myself into writing it. When I was writing it, I wasn’t thinking, “Oh, this is a novel. This is a full manuscript or project.” I wasn’t thinking anything. I was allowing it to be fragmented, almost like a series of essays, where each section had its own completed arc (which I later unraveled). I wanted to play on the page and have the scope be a bit smaller while I was writing. If I thought, “What is the through-line? What is the plot?” it would have been mentally strenuous, stressful, and scary for me. It was a mind trick. Then later, I unstitched it all and rewrote it.

FWR: When I read Bestiary, I was struck by the density of figurative language and how you use proverbs to explain the world. For example, “the moon wasn’t whitened in a day” and “burial is a beginning: To grow anything you must first dig a grave for its seed.” For me, these aphorisms are a kind of hand off into the myth and magic in your stories. You explain the world through the earth, through the body, through transformation. Your characters do not only feel that they have sandstorms in their bellies when they are sick—they literally have sandstorms in their bellies. Can you talk about the connection between language and transformation in your stories?

KMC: Wow that is so beautiful and profound! I think transformation is the perfect word. In a lot of ways, it is like casting a spell with language. Through metaphor, you turn something into something else. In the language, that is the reality. I had a teacher named Rattawut Lapcharoensap who wrote a story collection called Sightseeing. He told me that writing makes something possible that wasn’t possible before. I love that definition of writing—to make something possible. It is also very literal. You take a blank page and put words on it that weren’t there before. If you think about it that way, it isn’t so profound, but there is something magical about it to me. Regarding proverb and myth, I love that language can be embodied. Language isn’t just a passive tool to render something. The poet Natalie Diaz once gave a talk at my school, and she said in the alphabet, the letter A came from the skull of an animal, and that’s the etymology of the letter A.

FWR: I feel like you wrote that! Speaking of real histories embodied in language, many of your stories are metafictional. In your short story “Excerpt from the History of Literacy,” your novel Bestiary, and your forthcoming chapbook Bone House, you use myths, wives’ tales, epistolary, oral storytelling, and Wuthering Heights to inform your narratives. In your mind, what is the role of the metafiction for the plot at hand? How do other stories inform what is happening in your own work?

KMC: I love that you asked about metafiction because I’ve actually been thinking about this. It’s interesting because when people think metafiction, they think postmodern. They think that it’s a very recent thing to have moments of meta in fiction. Chinese literature is extremely metafictional. The beginnings of chapters will say, “In this chapter, here’s what you’re going to learn.” And then at the end of the chapter they’ll say, “to find out the end of this conflict, read on to the next chapter.” In a lot of translated Chinese fiction that I know and love, there’s this sense of artifice. I am constructing something for you, so read on to the next chapter, the next scaffolding. It shows you the performance of the fiction, which I love so dearly. It’s ancient, not experimental or new or strange—maybe it is to Western audiences. Regarding plot, I think there’s something very playful about reminding the reader of the fiction. It kind of breaks the expectation of realism, which opens up the possibilities—this is all a construct anyway, so why can’t you give birth to a goose? Why can’t you fly?

Regarding plot, I think there’s something very playful about reminding the reader of the fiction. It kind of breaks the expectation of realism, which opens up the possibilities—this is all a construct anyway, so why can’t you give birth to a goose? Why can’t you fly?

FWR: Earlier, you mentioned you write to fulfill your own expectations. In her lecture titled “That Crafty Feeling”, Zadie Smith says that critics and academics tend to explain the craft of writing (or, expectations) only once a text has been written—that is, after the fact of making. She says that “craft” is almost retrospective. It doesn’t really tell a writer how to go about writing, say, a novel. Does this resonate with you?

KMC: I completely agree! There are so many times where I’ve only been able to articulate my intentions, or what tools I’ve used to articulate those intentions, long after I’ve written the thing. Most of the time I don’t even know my own motivations, much less my own expectations, for writing a particular piece. I think that’s part of the joy and mystery of the experience – if I clearly know my own expectations and how I’m going to fulfill them, it tends to fizzle out quickly. There’s something about being a perpetual beginner, or at least feeling like one, that makes writing possible for me.

FWR: Have there been times when you’ve been given craft advice you refused to heed? What writerly hills have you died on? You’ve been lovely to work with from an editorial standpoint, but I wonder if there are times you feel the need to put your foot down.

KMC: I love getting edits and feedback because I’m constantly lost in the woods. I’m always asking what to cut—I welcome it! But I think I struggle with conventions of storytelling that we get told as writers. We internalize things like, “Make sure the narrator is driving the story and have an active narrator.” I’m really curious about stories that have characters who are caught in the eye of a storm—who are not necessarily driving the story, but are in circumstances where the world is what is moving them, because of status and who they are! This idea of an “I” narrator who creates conflict and action is a very particular way of seeing yourself in relation to the world that I don’t think my narrators have the privilege to experience. I have also been told, “Every word is necessary”—to have an economy of language. There’s an interview with Jenny Zhang in the Asian American Writers Workshop where she says, “I don’t want to be economical. I want to be wasteful with language.” I loved it so much I wrote it down. I fight against this utilitarian idea. Write toward the delight of sounds and words. Why follow this capitalist directive in the way that we write? I think breaking out of that is really important.

I fight against this utilitarian idea. Write toward the delight of sounds and words. Why follow this capitalist directive in the way that we write? I think breaking out of that is really important.

FWR: I like the idea of being wasteful with language. I think you could also see it as being generous with language.

KMC: Yes.

FWR: You talk about your characters not being as active. How do you go about developing your characters? I’m thinking about how Smaller Uncle in “Excerpt from the History of Literacy” is most vivid in relation to the details assigned to him—from the tendencies of his nose hairs to the way he fixes the “dumpster-dive TV.” Can you talk more about how you develop and discover your characters?

KMC: A specific phrase or voice will pop into my head and I’m like, “Who is this? Who are you? Why would you say this?” It’s always horror or shock at some terrible thought. It always comes from this place of curiosity. I want to know why this person is thinking this or doing this in a particular moment. The unravelling is discovering what happens. I sometimes stray completely from where I began, but character is really the driving force of my curiosity. I want to find out the circumstances under which characters do or say certain things. We often think that characters need to have individualistic, unique, instantly recognizable identities. But I’m really interested in collectives. People whose selfhood bleeds into their families and their communities, with lovers. I love the mutability of the self. I’m more interested in how selfhood doesn’t exist—the blurring of borders.

But I’m really interested in collectives. People whose selfhood bleeds into their families and their communities, with lovers. I love the mutability of the self. I’m more interested in how selfhood doesn’t exist—the blurring of borders.

FWR: Do you have any favorite literary characters?

KMC: In Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen, there is a character called Moonie. The book begins as a revenge story, and I love revenge. I love this character and this book! I also have a huge weakness for Wuthering Heights. I am endlessly fascinated by any character from Wuthering Heights. I may not ever want to meet them or interact with them, but I have endless fascination. There are so many mythical characters I love from different mythologies. There is a snake goddess who is also a giant snail sometimes. I’m delighted that she’s a giant snail. Yes, I love that. Her myth is that she creates the world and creates people out of mud. We’re all just snails!

FWR: I’ve always felt that way. So, what are you reading right now?

KMC: I’m rereading a book that’s coming out in July from my publisher, One World, called Ghost Forest by Pik-Shuen Fung. I also just read a book called Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge. It’s coming out from Melville House and is one of my favorite books of all time. The myth, the uncanniness, the strange beasts—I feel like the title is self-explanatory. It broke me out in a cold sweat the whole time, but in the best way. I have this goal for myself that will probably never happen to read all four classic novels of China. One of them is Dream of the Red Chamber, which I have read, and Water Margin, which is about bandits. I love writing about pirates and I feel like bandits are of the same branch, so I want to start reading that.

FWR: Thanks for the recs! Before you go—any thoughts on the pandemic’s impact on your writing?

KMC: In terms of the actually sitting down and writing, not much has changed. For me, there is an increased sense of urgency in wanting to tell certain stories that are in a community. Before Covid, my stories were about interwoven webs of community. That’s very important to me, and this was heightened during the pandemic. Part of that is because I spent a lot of time with my family in the hustle and bustle of a very large household. I remembered what it was like to be surrounded by voices and storytellers all the time. Being home rerouted me in what I wanted to do. Being solitary helps me write, though. I try to create that solitude. When I was living at home, I had this habit of writing in ungodly hours of the night. At first, I thought it was because I am such a night owl, but really, it’s because I was alone. When everyone in the house was either out or sleeping, everything was muted. The windows were so black I couldn’t see out into the world. I felt so alone, and it almost created my mood. I needed to enter that space to be with myself. I needed the solitude of night pressing in.

- Published in Featured Fiction, home, Interview, Monthly

MONTHLY: Chapbook Conversation

The chapbook is a strange and protean form, flickering somewhere between long poem and short book, and though they get little love from reviewers, prize committees and large publishers, many of us write, publish and love them. So, in January, I sat down with three poets whose chapbooks I’ve really enjoyed, to talk with them about our experiences writing (and shilling for) these little fascicles, and how we did (or did not) weave them into full-length books. Conor Bracken

Conor Bracken is the author of Henry Kissinger, Mon Amour (Bull City Press, 2017), selected by Diane Seuss as winner of the fifth annual Frost Place Chapbook Competition, and The Enemy of My Enemy is Me (Diode Editions, June 2021), winner of the 2020 Diode Editions Book Prize. He is also the translator of Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s Scorpionic Sun (CSU Poetry Center, 2019). His work has earned fellowships from Bread Loaf, the Community of Writers, the Frost Place, Inprint, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and has appeared in places like BOMB, jubilat, New England Review, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and Sixth Finch, among others. He lives with his wife, daughter, and dog in Ohio.

What the Chapbook Allows For

“[The chapbook was] a more dense approach. [The poems] are more focused… Because I am so blobular and sprawly…the chapbook helped me so much with the [full length] book… You know when cells sort of… create an internal circle and expel something? Endocytosis! This little nucleus started forming within the blob [of a bigger idea], and that became the chapbook. That helped me center around a specific object, and a specific line of thought, and it became a guiding principle. A concrete thing to work around. [The chapbook] helped me in eliminating all the things that did not belong to it.” Ananda Lima

Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land was the winner of the 2020 Hudson Prize and is forthcoming in 2021 (Black Lawrence Press). She is also the author of the poetry chapbooks Amblyopia (Bull City Press – Inch series, 2020) and Translation (Paper Nautilus, 2019, winner of the Vella Chapbook Prize), and the fiction chapbook Tropicália (Newfound, forthcoming in 2021, winner of the Newfound Prose Prize). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark.

Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land was the winner of the 2020 Hudson Prize and is forthcoming in 2021 (Black Lawrence Press). She is also the author of the poetry chapbooks Amblyopia (Bull City Press – Inch series, 2020) and Translation (Paper Nautilus, 2019, winner of the Vella Chapbook Prize), and the fiction chapbook Tropicália (Newfound, forthcoming in 2021, winner of the Newfound Prose Prize). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark.

“For me, too, [the chapbook] was so much more fun…! The chapbook is just a really wonderful time. It’s really one of my favorite parts of my writing life so far.” Taneum Bambrick

Taneum Bambrick is the author of VANTAGE, which won the 2019 APR Honickman First Book Award. Her chapbook, Reservoir, was selected for the 2017 Yemassee Chapbook Prize. A graduate of the University of Arizona’s MFA program and a 2020 Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, her poems and essays appear or are forthcoming in The Nation, The New Yorker, American Poetry Review, The Rumpus and elsewhere. She teaches at Central Washington University.

Taneum Bambrick is the author of VANTAGE, which won the 2019 APR Honickman First Book Award. Her chapbook, Reservoir, was selected for the 2017 Yemassee Chapbook Prize. A graduate of the University of Arizona’s MFA program and a 2020 Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, her poems and essays appear or are forthcoming in The Nation, The New Yorker, American Poetry Review, The Rumpus and elsewhere. She teaches at Central Washington University.

“There was something more fun about the chapbook process, because it almost felt like you didn’t know what the expectations were… Because the big book is like “This is the BIG BOOK… Oftentimes we’re so used to seeing our poems in our Microsoft Word frame-world, that it was such a huge thing to me when Ross sent me my first mockup of my book… Going through those small processes, having the object, giving your first reading with the book, and going through all those on a smaller level, to me was such an added boost in getting to the big book process.” Tiana Clark

Tiana Clark is the author of the poetry collection, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018), winner of the 2017 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize, and Equilibrium (Bull City Press, 2016), selected by Afaa Michael Weaver for the 2016 Frost Place Chapbook Competition. Clark is a winner for the 2020 Kate Tufts Discovery Award (Claremont Graduate University), a 2019 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, a recipient of a 2019 Pushcart Prize, a winner of the 2017 Furious Flower’s Gwendolyn Brooks Centennial Poetry Prize, and the 2015 Rattle Poetry Prize. She was the 2017-2018 Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing.

Structure

“I looked at each of the sections of my big book as actually three different chapbooks. And that helped me break down the aerial view into sizeable chunks to help me manage it mentally and emotionally.” TC

“I’m writing these poems and then I see that there’s a sort of theme emerging, and there’s a lot of poems that are talking to each other and are tending towards certain subject matter or a mood. At first I’m just thinking of the poem as a poem, and then I’m thinking of this blob… This is my book—the blob!

For me, the difference between the blob and the chapbook was just that there was a conversation crystallizing around this nucleus… Find and create bridge poems: Look for poems you might have thought about including in your chapbook, but decided not to because they veered away from the chapbook’s core. You can also do this with new work, work-in-progress, and even notes on poems-to-come. The goal is to find poems that speak to the work in the chapbook, but don’t neatly fit into it. Use that intersection to expand the work into new threads to be explored for the full length.” AL

“Think about your favorite book of poems. There’s probably only 5 or 6 poems that come to your head… If you have 5 or 6 fire poems, then you’re ready to go… Also…make sure everything looks beautiful and perfect. It starts from the table of contents. Those are like little chapter novels!” TC

“What do you feel is missing? I don’t mean “missing” in a negative way, but rather as gaps where more risk, information, and urgency might enter into the project. What did you carve out through the editing process? Do you still have those drafts? Who told you to throw them away? The process of editing a chapbook, at least for me, was so influenced by institutions: some of what I removed initially, or didn’t feel brave enough to pursue, were poems and essays that represented the most authentic parts of the experiences I was describing.” TB

Audience

“Thinking about the audience in the process of composition and even assemblage can be paralyzing. I love how chapbooks can unfetter us from our own expectations of ourselves so that we can write without an audience, that doesn’t even exist, breathing down our necks…and can also give us this kind of tailwind we need for the next stage.” CB

“I did a mini-chapbook tour…and I was reading at mostly bars in random places…and I was just writing down questions people had for me, so I would hear where the gaps were, [the] places where I was resisting something that felt risky or where I hadn’t written yet something that might be the most vulnerable.” TB

“I often don’t think about the audience, even in general. I saw Terrance Hayes in an interview talk about how in his first drafts the audience is never in the room, it’s just [him]and [his] shadows and [he’s]just exorcising everything out. Obviously, we think about the audience at some point, which for me is revision, or publication. I always tell my students there’s the poems you write and the poems you publish.” TC

“Using submissions as a thing in your writing process …is very true for me too. I find that the revisions I do before the deadline are so much better than the ones I’ve been doing for months. That’s when the audience comes in… It makes it easier to imagine other eyes reading that.” AL

Submitting

“I was unable to publish the poems individually because my book is very much narrative-driven, so if you extract individual parts, they don’t really make sense. I was encouraged by my workshop leaders at the University of Arizona to pursue chapbook publication.” TB

“[The thought process was] I think I have 15-20 poems in conversation, let me submit to a chapbook competition. I make it sound so haphazard but that’s kind of how I was… I looked at submission deadlines at the time as a way for me to help with my revision process.” TC

“Having that editing process helped me understand what I had here [in this chapbook] that belonged to the other [bigger] book.” AL

“I got a handwritten rejection from Bull City. It was so cute! I remember carrying that handwritten note around. I had it on my wall in my room because it was so important to me. It was the first time anywhere that I considered to be a really big deal publishing place had ever spoken to me. It was this intense breakthrough that gave me the motivation to submit it… I look back on how dramatically that changed my idea of myself. From that note on, I went from writing by myself to writing in community.” TB

“If you got a personal rejection, whether that’s for an individual submission or for a chapbook or for a big book prize…the fact that someone took the time is a really big thing, and it’s also a sign you’re getting closer. I love that quote from Sylvia Plath: ‘I love my rejection letters, they’re signs that I tried.’” TC

How much of the chapbook became ‘the Big Book’?

“When it got to the Big Book for me, [the big book] definitely had a theme…after you do the mini-tour [for the chapbook] and get the little amuse-bouche of what’s happening, then it helps you for the Big Book. I was like, what conversations do I want to be having, what do I want to answer in Q&As and interviews, because I got a taste of that with the chapbook… [For the chapbook and the big book] I let those voices haunt me in a different way.” TC

“[I had] my fears about having too many of the same poems in the chap and the full-length, and worrying about the audience in that way and trying to figure out how to make [the poems] different. I ended up with almost all the poems from my chapbook in my full-length, so that felt like a really big risk… My chapbook had a quieter reception, so it didn’t really matter that much. But the biggest difference is that I was really interested in hybridity and including essays alongside poems… The difference between the chapbook and my book is pretty much the risk of hybridity and the risk of engaging in those traumatic, scarier, more personal details.” TB

“I was worried that everyone had read some of these poems. Because it felt like more of a book than a chapbook for me, I kind of let it go. “This is its own thing.” The full-length became a challenge of creating a newer object and I want them to have two separate worlds. I think I only have 2.5 poems…from the chapbook in the big book. What are poems that are absolutely in this other conversation? But I gave myself permission to let my chapbook be its own thing and just kind of put it on a boat and pushed it away.” TC

Direct Advice

“What are some guiding principles? ‘Every good book—whether that be a novel, a linked short story collection, or a sequence of poems—starts with an unanswerable question.’ And the protagonist…struggles with that, trying to answer that question, and never does, but it’s that tension that creates the narrative arc.” Charles Baxter via TC

“Having good teachers is really important for [learning to embrace risk] and identify what [you’re] avoiding.” TB

“The workshop is a voice but not the voice. [It can] sanitize risk.” TC

“One thing my professor [Mark Jarman told me about impostor syndrome], this grand professor with all these books, he was like “oh, you’ll have that for the rest of your life.” He said it so matter-of-factly and there was something about that that was so comforting, so I was like oh, so this is not something to overcome and the fact that I’m feeling that is very much in line with being a writer. Once I realized it was insurmountable, I was like oh, I got this. So I alchemized that energy.” TC

“Find unexplored threads in your chapbook: Talk through your poems with a generous friend (or an imaginary friend, if you are good at pretending). Go through each of the poems in your chapbook and have fun geeking out on what you did (eg. “the line break here does X, isn’t that cool?”, “I used this word here because it can also mean X,” etc). Sometimes talking about poems in the way, you find themes that are under the surface, that you could explore them in more depth in a full collection. The friend can stay silent or they can ask questions (eg. “where do you think this word is going?”), as long as you both understand that this is not a workshop but a generative exercise looking for nascent threads in the chapbook.

[In terms of emotional management] Feel great about yourself and your accomplishment. You wrote a chapbook and that is awesome. Remind yourself when you didn’t have a chapbook at all and the time when you were anxious about a fledgling something in your hands, unsure of where it would go. Remember this and use it to keep yourself going through some similar anxieties when writing your full-length collection.” AL

MONTHLY: Fiction Editors Emeritae

GIRLS OF LEAST IMPORTANCE by K.K. Fox

K.K. Fox lives in Nashville, Tennessee. Her stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Iron Horse, NELLE, Joyland, Kenyon Review Online, and others. She is a fiction editor for Los Angeles Review.

THE LUCKY ONES by Hananah Zaheer

Hananah Zaheer’s writing has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, SmokeLong, Southwest Review, AGNI, Michigan Quarterly Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. A flash chapbook, Lovebirds, is forthcoming from Bull City Press. She is fiction editor for Los Angeles Review and is currently working on a novel. You can reach her at @hananahzaheer.

GIRLS OF LEAST IMPORTANCE by K.K. Fox

It wasn’t like you think. Charlie Todd was one of the most popular candidates going through Rush that year, even with a limp and a useless hand. We tried not to stare, but her left arm was lifeless, paralyzed, and her hand curled at the end like a comma. She hit her head in a car wreck just before high school. We heard it from Brea Loveless who knew her before it all happened.

That year, we held seminars at Rush Retreat about the importance of diversity and acceptance on the University of Tennessee’s campus. The school was pressuring Panhellenic to be more open, but our sorority was ready. There was a mixed girl going through Rush, and not only was she gorgeous, but a lot of girls didn’t even notice she was any different from us until we pointed it out. We hoped a Muslim girl might apply, but they usually stuck to International Club, and we couldn’t do a Greek mixer with a club. But we asked the AKA girls to choreograph our step routine for the Panhellenic Dance-off last year, and we felt really good about that.

The University of Tennessee had fourteen Greek sororities, but there was an unofficial top four. The Zeta Thetas, or the Zluts, were local Knoxville girls. The Chi Omicron Phis, or the Chi Babies, were all cotton money from Memphis. The Eta Eta Etas, or Eat Eat Eats, were chubby rich girls from out of state. And the Kappa Omegas, or the Knock Offs, were Nashville private school girls who couldn’t get into Vanderbilt. If those four wanted Charlie Todd, then the rest did, too. And since Charlie Todd was from Nashville and her younger sister was already a Kappa Omega, they acted like Charlie was theirs. But we knew the rumors—that Mamie and Charlie weren’t even close. That Mamie didn’t want her sister around in high school, so she wouldn’t want her in college, either.

They used to be close, or so Brea Loveless told it. She said they were once almost like twins, laying hands on each other’s arms like they were extensions of their own. Access to each other’s minds so that they didn’t need words. But something changed in the accident—Charlie did. Mamie didn’t have any injuries, but she got fat and quit the color guard. We heard it straight from Brea.

Since Charlie was the only special needs girl going through Rush, she basically had her pick. She didn’t need a wheelchair, but we all had ramps and elevators in our sororities because our houses were new. Tennessee used to have this law that if seven or more women lived in a house, it was considered a brothel, an old law never struck from the books. But donors speak louder than old laws, so UT finally let us build Sorority Hill, just like Fraternity Row. The frat houses were outdated, filthy brick boxes from the 70s. But the sorority houses were state of the art, totally accessible for the handicapped, and decorated with the principles of feng shui.

During Rush, the candidates came to our house for three different rounds. When Charlie showed up, she was wearing jeans and a pink gingham top. It was a little informal next to all the sundresses on the other pledges, but we still guided her to a wingback chair that faced the party—total privileged status. Girls of least importance had to stand in the middle of the room. We knew which candidates needed more attention and gave the others a passing hello because we only had so much time. It just wasn’t possible to love everyone equally.

The mixed girl, Nicole, and Charlie came through the same party that round, which meant we had to buzz back and forth between them. We needed to keep Nicole and Charlie’s undivided attention so they didn’t have time to look around. Or think. We needed them to choose us.

“They could have put them in different groups,” Mindy Thompson said. “That makes the most sense.”

Nicole was a rising freshman from Knoxville, and so she was friends with all the Zetas. We had a lot of work to do. We showed her our median GPA was higher than the rest of the sororities’ and that our house was the smallest on Sorority Hill only because it was first. Our Nationals built us a house when the other sororities had to raise funds locally. They weren’t strong at other universities like Alabama, Ole Miss, or Texas. Not like us. We preferred being a sorority whose national presence mattered more than one single chapter in Knoxville. We told her we were part of something bigger and more important with lots of different kinds of people.

“Do you ever do anything with the other chapters?” she asked.

“If you see another sister in public, you do a secret sign. If she sees you, she does it back.”

“Oh, so then do you introduce yourself?” she asked. “Like is that how you meet each other?”

“Well, no,” we said. “You just smile at each other and keep going.”

“Then why do it?” she asked. Every time we saw someone in a T-shirt with our letters at the airport, we made an O with our fingers and thumb and held it over our heart hoping the girl would notice. If she did, she would do it back, and we had that thrill of a mutual secret.

“It’s fun to show each other we’re the same,” we said.

Nicole looked down at her hands and picked at her nails. They were unpolished and short. A biter.

“So you like being a part of the same club.”

“Exactly,” we said. “Who doesn’t?”

*

As a rising junior, Charlie was an unusual candidate. She was a year older than her sister, waiting until after Mamie joined a sorority to do so herself. We gave most of our pledges to freshmen because they could invest a full four years in the chapter. Becoming one of the best sororities was about consistency and lower turnover, but including someone with a disability would show just how inclusive we were, unlike everybody else. If we wanted the chapter to survive, we had to show the world that we weren’t just shallow, pretty girls who threw great parties. We were open-minded; we were inclusive. Anyway, no two people were completely alike, so really, we were all the same in that.

“What’s your major?” we asked, and Charlie said it was interior design. We thought that sounded feminine. She was a talker, which was great, because it can be hard to think of things to say with girl after girl after girl. As Charlie talked, she pulled on her paralyzed hand with the other one, stretching out the stiff fingers and massaging the wrist.

“Does it hurt?” we asked, and she said she was supposed to wear a brace, but she didn’t like the way it looked. We all could understand that.

“Beauty is pain,” we laughed. We couldn’t wait for lunch.

*

That night, whispers spread from house to house. No one was supposed to have any contact with pledges outside of the Rush parties, including real sisters like Mamie and Charlie Todd. However, a Rho Chi said she saw Charlie and Mamie go into Gus’ Good Times Deli together and that Mamie hugged Charlie as they stood in line to order.

“That’s against the rules,” we cried. We heard the rumors, that they didn’t normally hang out. That they weren’t close. This felt like Mamie trying to make up for lost time, trying to win her sister over only to get her into her sorority. Mamie had her whole life to be nicer to her sister. We weren’t supposed to talk to the Rho Chis either, but everyone broke that rule, and everyone knew everyone broke that rule, so that was different.

“Just because they’re sisters doesn’t mean they have to be in the same sorority,” the Rho Chi said. “They’ll always be sisters.”

“That’s it,” we said. We knew exactly how to convince Charlie to leave hers.

*

During the next Rush party, Charlie arrived in a pencil skirt, white blouse, and kitten heels. She looked like she was going to a job interview, but some of the freshmen were showing too much cleavage, so Charlie looked classy by comparison. And if she joined our chapter, there would be plenty of time for style advice.

She wobbled in her heels as we guided her to her seat. This was the round where we performed a show about our chapter, a skit passed down since the early 90s. We had a mermaid who looked like Ariel. She floats about trying to figure out where she belongs. She finds her sorority home in a chapter filled with all kinds of other sisters: mermaids and humans and sea creatures. The skit emphasized our tradition of diversity.

“You know,” we said to Charlie. “Ariel could have gone to the sorority with all the mermaids she already knew, but that’s not what finding a sorority is about.”

“I love the costumes,” Charlie said, smoothing her tight skirt with her right hand as if it, too, were a fin.

“You’ll find all kinds of people in our chapter,” we said, just as we practiced. “Your friends will always be your friends, and your family will always be your family.” We let this last part sink in for a moment. “Joining a sorority is about finding the right place for you.”

“Everyone I’ve met during Rush has been so nice,” Charlie said. “I’m not used to it. It’s like I suddenly have something that other people want.”

“Not suddenly at all,” we cried. “We just want you. And we sure hope we will see you back here for Preference Night.”

“Oh, yes,” Charlie said. “Preference.”

After the party, and after we closed the door behind the last candidate, we thought through what Charlie said. Would she cut us? Would she come back? Only the Chi Babies had cut Charlie so far. That sorority would cut a girl just so the girl couldn’t cut them first. They were afraid of rejection, of risk. But how else do you become sisters?

*

When we got the list of returning candidates and Charlie’s name was on it, we clapped and squealed. Apparently, she had chosen Eta Eta Eta, Kappa Omega, and us as her top three. We couldn’t believe it. We were bummed that Nicole had cut us, but we knew the Zetas were hardcore rushing her since she’d gone to high school with half of them. She must not have cared the Zetas weren’t progressive, not like us. Maybe she was as predictable as any other girl.

The Kappa Omegas still had the best chance of getting Charlie because they had her sister, but we were determined to make her think twice. She arrived on Preference Night wearing a lacy mint green dress that stopped just below her knees, an awkward length, as if she had gone into her mother’s closet and picked one of her dresses. Her shoes were flats, no more heels this time, so no worrying about her turning an ankle as we crossed the room. We gave Charlie the best seat in the house, at the front but to the side so she could see the rest of the desirable candidates around her. They would all have a front row view of Mindy Thompson, our soloist, who would sing a moving song sure to make them all cry.

Every candidate had one of our sisters sitting at her feet, talking to her about the sorority and how excited we would be to have that candidate run through our door on Bid Day. Kat O’Donnell sat on her knees in front of Charlie where she could touch Charlie’s knees and hands like they were old friends. Kat was the best sister for the job, because she pledged a different sorority than her older sister. Granted, they went to different colleges—not like Charlie and Mamie Todd. But it was our best chance to convince Charlie she didn’t have to pledge a sorority out of obligation.

“I thought a lot about my decision,” Kat said, who raised up on her knees, leaned in to Charlie. “But I knew when I met these girls that this was the place for me.”

“I’ve met so many, it’s kinda hard for me to tell them apart,” Charlie said, and she looked around at our candles, our flowers, our balloon arch with a microphone stand. The entire patio smelled of gardenias, both in the vases as centerpieces and the perfume we sprayed all over the tablecloths. Next to Charlie was a teacake with her name scrawled across it in icing. Charlie took a big bite, and our stomachs rumbled. Usually, the candidates were too nervous to eat much of their teacakes, so as soon as they left the party, we swarmed the tables, scarfing up their leftovers before clearing the plates and setting down new cakes for the next party. We were both hungry and concerned watching Charlie eat her cake with her one good hand and lick her fingers. An appetite was never a good sign.

“You know,” Kat said. She was about to deliver our final whammy for winning Charlie over. “My sister got to pick her own sorority. Why shouldn’t I have that opportunity, too?”

Charlie chewed the remainder of the teacake in her mouth while nodding. Then she swallowed. “Well, I guess it’s the one time you actually can choose your family.”

Kat’s mouth fell open a little, and we all stopped breathing. Kat sat back down on her heels, flustered. Then, Mindy started humming under the balloon arch with a hand to the microphone. She looked at her feet while the speaker played a Steven Curtis Chapman song. She swayed with the intro and opened her eyes on the first piano note.

Mindy was good at this. As a senior, this was her last Preference Night. We fretted over who would do it next year. A freshman would be best, someone who could deliver the same performance for three straight years. Our Rush process had to be honed for results. Sure enough, the girls near the front dabbed at their eyes with their napkins, their uneaten teacakes in our periphery. One pledge near the back was in full sobs, and we felt bad, because she was just a seat filler. Not every girl can get a bid, but empty seats look bad, so unlike Chi O we kept a few around who were easy to vote out. Some of the seniors were crying genuine tears and hugging each other, as this was their last Preference Night before their last year of date parties and chapter meetings before going separate ways into the world. But Kat O’Donnell turned on the water works like we knew she could. She looked up at Charlie as a few tears—but not too many—slipped down her cheeks. She squeezed Charlie’s curled hand between her two. With the other hand, Charlie finished off her teacake, crumbs landing on her pooched belly as she relaxed in her chair. She probably couldn’t work out very well with her condition, but we could help her understand nutrition when she was eating meals in the house with us. She took a sip of punch.

At the end, Kat walked Charlie to the door last. We all reached out, tapped Charlie’s shoulder, waved goodbye. We used her name.

But when we closed the door, Kat O’Donnell broke down in real sobs, sinking into a nearby chair. We crowded around her, petting her head and offering her tissues.

“What’s wrong?” we asked, and Kat looked up, mascara streaking down her face that was crumpled in an ugly cry.

“I didn’t choose my family,” she said.

*

The next morning, we got our list of confirmed pledges. We scanned for Charlie’s name first and slumped when we didn’t see it.

“That’s okay, girls,” our Vice President of Membership said as we stood in the chapter room holding hands in a circle while wearing matching pink Bid Day shirts. “We tried our best. Just know it’s not our fault.”

We stood on the front lawn and faced the courtyard where the next generation of pledges were barricaded behind curtains of crepe paper ribbons. On the Rho Chi’s count, the pledges burst through the streamers and ran full speed to their new homes. We greeted them with hugs and squeals and matching T-shirts.

Charlie couldn’t run, so she limped along last, shuffling toward the Kappa Omega house. We knew it. We just knew it. They had her actual sister; we could never compete with that. It was so unfair. We spent all that time on her for nothing.

Our new class of pledges bounced around us, blond highlights flying about. We couldn’t help but look over their shoulders as Mamie met Charlie between the courtyard and the Kappa Omega lawn. They stood inches away, but they didn’t hug. Mamie was saying something, then put her face in her hands like she was crying. Charlie moved forward and wrapped the one arm she could around her sister. They stood like that for a minute, and it looked sad, and for a brief moment we wondered if maybe Kappa Omega had not given Charlie a bid after all.

But then Mamie took Charlie’s good hand in her own, and they walked back to the Knock Offs, who all started swinging their right arms with fists in the air, singing their sorority song: Drink a toast! To the Kappa O’s! The greatest girls I know…

Charlie joined them, swinging her arm, too, her fist in the air, certain and proud. The KO’s swarmed her with their ponytails and tears. We watched her until we couldn’t, until she blended in to the crowd and became a Kappa, too. They were all moving the same direction at the same time in the same way.

That’s when Kat O’Donnell clapped her hands and stomped her right foot. We stomped along as our new pledges looked at us with wonder, so happy that we chose them, as if we would never choose anyone else. We would never choose differently. And so we circled them, everyone crying and laughing and hugging, and we sang louder and louder so the other sororities could hear us. So that our own voice was unmistakable. We sang so that they would know just how happy we were.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Monthly

THE LUCKY ONES by Hananah Zaheer

Ever since Abba died, a girl has been living in my mouth. Mostly, she sits on my tongue and watches me do my homework or make houses with old cereal boxes. When Amma makes me write receipts for the laundry business she runs out of our living room, the girl helps me count.

“I want to have fun,” she says some days. “Don’t you want to have fun?”

I tell her this is all the fun we can have right now. If Abba was still alive, we would go to the park and sit on the carousel and go around and around till the sky tilts. With Amma, I only get to watch as she walks from sofa to sofa, making foul-smelling hills out of other people’s clothes.

“Imagine if she was the one who died,” the girl says. “Do you think your father would come back to life?

Sometimes the girl doesn’t like being made to eat daal four days in a row or doesn’t want us to go to school or doesn’t want Amma to try to suffocate us with her hug and then she gets angry. She slides down my throat and sits on my heart, her legs wrapped around it. When she squeezes, I have to breathe deeply to keep from crying.

“What’s gotten into you,” Amma keeps saying and stares at me hard like she can tell I am hiding something. I squeeze my lips together tightly so she can’t see inside my mouth. She would send the girl away and I can’t have that: the girl is my only friend.

One morning when Amma says we are going to Billy’s house because his mother has died, the girl jumps into my stomach and pinches my lungs.

“Let’s go,” she says. “I have an idea.”

Billy is the luckiest boy in my grade, maybe in the world. Everyone at school likes him. He comes to school in a white Corolla with his father, who smells like oranges and wears sunglasses and looks like the man on the movie poster at the theater across the street from my house. Sometimes, Billy’s father stops by our house with a bag full of dirty clothes and while Amma and he discuss business in the bedroom, I sit with Billy on the balcony and pretend he likes me. He tells me he loves scary movies. Once he told me he watched a movie where one man hooked up a tube to another man’s arm and drank all his blood.

“Took all his power,” said Billy and snapped his fingers. “All his luck, too. I have two copies of the DVD at home.”

“Can I come over to watch?” I asked, and he looked at me like he ate something rotten.

“What if he was right?” the girl in my mouth says now. “What if you could change your luck by tasting the blood of someone lucky?” She crawls along the sides of my teeth.

Amma points at the plastic bag someone dropped off only the night before. “Wear the black dress,” she says. “I’ll clean it later.”

The wool still smells like its owner’s sweat. I hold my breath when I squeeze in. Then I slide Amma’s pearl hairpin into my hair.

“Please,” I say when she frowns. When she turns, I slip it into my pocket.

The whole taxi ride from the other side of I-40, the girl leaps from my stomach to throat to heart. She plans.

I imagine Billy’s blood will taste like thick honey. I imagine this of all the kids at Julius West Elementary. They are loud and happy and play only with each other.

“It’s because they’re different,” the girl tells me. “You can’t do anything about that.”

Most days, at recess, I hide behind a bench and poke my own palm with the pearl hairpin until red dots ooze out. I lick the dots and wish for something spectacular to happen to me: to break my leg or to become so sick I have to spend weeks in the hospital, to get electrocuted and wake up in a world where Abba isn’t gone; he is just visiting some place he had always wanted to see—New York, Arizona, Los Angeles. Then, the girl would have never come to live in my chest.

At the end of the gravel driveway to Billy’s house, Amma fixes her makeup. I feel the hairpin in my pocket.

“Behave like we belong,” Amma says. She dabs perfume onto her wrists and behind her ears. Her breath smells of onions and toothpaste. I hold my arm out.

“Not for little girls.” Amma pulls her hand away, tucks the perfume deep inside her bag. Then she knocks at the door.

“Stupid bitch,” says the girl.

Billy is in the living room, his bony legs look like an unsteady colt’s. The grownups can’t keep their hands to themselves. He is getting hugged and kissed and offered tiny sandwiches. When we walk to him, he crosses his arms and kicks the leg of the coffee table. His mouth puckers. My face gets five-slaps hot. At home, Amma made me practice saying, “I’m sorry about your mom.”

“Don’t say it,” says the girl. I listen. Instead, I gather my hair under my chin and bite the ends.

“Don’t you want the kids in school to make you a big card, to crowd around you at lunch?” asks the girl.

Amma stands close to Billy and his father, their three pairs of feet nearly touching. I peer at the bottom of Amma’s chin. The skin near the bone is thin, like the veiny bubble of a frog’s throat. Bruises appear on it easily: mosquito bites or finger marks or a blood spatter like a tiny man had fallen off a balcony onto a tiny sidewalk inside her neck, cracking his head open.

I could pierce it easily when she sleeps quietly on the couch, I’ve told the girl. But she tells me I don’t need Amma’s blood.

“She’s just as unlucky as you,” says the girl.

Billy’s eyes are wet. His hair falls onto his pumpkin forehead. He pulls at the end of his too-big, too-long shirt. The girl starts climbing up to my throat.

“Why are you here?” Billy’s neck is red and splotchy. His seems sad and small, nothing like the boy from last week when he had led a half-circle around me in a chant. Daughter of a bitch is a bitch, bitch, bitch.

“No one likes her,” he says and points at me.

My knee is still a thick scab from fighting him to the ground.

“Last warning,” Principal Miller had frowned when Amma came to pick me up after the fight. “One more incident like this and you’re gone.”

“Tell Fatface Miller to shut up,” the girl had said.

“I don’t care,” I had said, instead.

Outside the school, Amma called a taxi and we rode home silently. Before bed that night, she breathed prayers into a glass of water.

“Drink this,” she said. “Maybe it makes you nicer.”

Amma’s palm is against Billy’s cheek. “This is a sad time.” She is using her bedtime-story voice. “It’s okay to be angry.”

I’ve heard this voice before. When we were new to America and I missed the stray cats outside my grandparent’s house in Lahore, she used that voice to tell me the cats missed me too. Later, I would hear her calm Abba on the other side of my bedroom wall. When she stopped using the voice was when everything went wrong. Abba got angrier. Amma started shouting at him. I move closer to her.

Billy’s face twists and then his entire body pulls away.

“Oh,” Amma says, and it looks like a deep sadness is pulling at her lips from the inside. She retracts her hand, holds it against her chest.

The girls says, “She would have swung it against your cheek if that had been you.”

“Son.” Billy’s father taps his head in warning.

“It’s okay,” Amma says. “When someone close to you is gone, you feel abandoned, angry. I understand.”

“She doesn’t understand you,” says the girl.

I pull at Amma’s sleeve, the girl in my stomach. “I’m hungry.”

“I’m sorry,” Billy’s father says.

“I’ve been there,” Amma says again.

The girl is unhappy. She twists inside my throat. I can feel her climbing to the back of my mouth. I imagine she’s on some sort of knotted rope.

“You’re not going to take that,” says the girl. “Say something.”

I shake my head.

“You can’t come to my house,” Billy says to me. His father squeezes his shoulder.

Amma is looking at me. I wish she would say something nice to me, but she looks like she is ashamed, saddened that I could make someone else so upset.

“She only cares about him,” says the girl, and swings against the roof of my mouth. “Everyone cares about him. Tell him to go to hell.”

“I can go where I want,” I say to Billy. I open my mouth wide to show him the girl swinging wildly.

“Stop it,” Amma says.

“Weirdo,” Billy says.

“Kick him,” the girl says.

I do. The kick is loud, Billy’s cry even louder, and before I know it, he has run away somewhere and everyone is looking at me and the skin on my arms is burning in Amma’s grip.

“What is wrong with you?” Her eyes are dark. “Why can’t you be normal?”

The room goes quiet. I can hear everyone’s breaths, in out, in out. The girl is angry. She wants to climb out of my mouth, to fly around the room and kick everything in sight. I squeeze my lips together.

“Go, apologize.” Amma’s jaw is tight again.

“I don’t know what to do with her.” She says this to Billy’s father and they both look at me in the same, disappointed, way.

Behind the door with a blue rocket ship, Billy is in a caterpillar curl on his bed. He is crying.

“He’s stupid,” says the girl.

“You’re stupid,” I say, not knowing what else to do.

“This house is stupid,” the girl says.

“Your house is stupid,” I say.

“Go away,” Billy says.

“Stay,” says the girl.

I close the door behind me. Billy is clutching his stomach.

“I hate you,” he says. I know he means to be angry but his chin trembles, and he sounds weak. On his bedside is a picture of his mother and him. They are standing in front of the Statue of Liberty. They are smiling.

I sit down next to him. Billy wipes the trickle from his nose on the too-big sleeve of his shirt. I trace the edge of the spaceship on his bedcover. He tucks his hands between his knees.

“He misses his mommy,” the girl says.

I pinch the skin on my hand and wonder what Billy’s eyes would look like if I pricked his neck.

“Here we go,” the girl says. She is sitting on my teeth now. She is nudging my tongue with her feet. I pull the hairpin out of my pocket.

“Are you going to cry?” I ask Billy.

“What do you want?” A tear falls down his cheek, then more.

His face is doing ugly, sad things. I can feel the end of the pin in my palm. Abba would have wiped my eyes if he saw me looking like Billy. Abba would have held my face. My chin quivers.

“Stab him,” says the girl. “Do it.”

I want to. I want to listen to the girl and stick the pin in him. I want Abba to come back. But he looks so tiny and sad, I can’t bring myself to do it. Instead, I lean in and kiss him. I press my lips against his wet slug mouth.

“Ew.” Billy’s head jerks back and he wipes his lips. “What are you doing?” Then he laughs, a small laugh that sounds a lot like his laugh from the playground, like he is better than me, like I could never be like him.

His face is still ugly, but he no longer looks sad. I imagine he will tell everyone at school about this. I imagine they will all whisper about me at lunch. My ears already burn. The girl is awhirl inside my head. Somehow she is in my arms and my legs and my stomach all at once.

I grab Billy’s shoulder and lean in and bite him. Then he punches me in my chest.

“You’re crazy,” he screams and scrambles off the bed. He is holding his mouth.

“You’ve done it,” the girl says. “We’ve done it.”

I can’t breathe because now the girl is dancing. She is in my chest and then in my stomach and then in my legs and back in my throat. Billy is still screaming. His blood tastes just like mine: coins and salt and water. There are footsteps thudding up the stairs. I slide the hairpin into my hair, just above my ear. I imagine Amma will slap me five times, six times. She will take me home in silence and lock me inside my room. And tomorrow, I will be lucky.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Monthly

MONTHLY WITH Rosalie Moffett

FOUR POEMS

INTERVIEW

Rosalie Moffett is the author of Nervous System (Ecco) which was chosen by Monica Youn for the National Poetry Series Prize, and listed by the New York Times as a New and Notable book. She is also the author of June in Eden (OSU Press). She has been awarded the “Discovery”/Boston Review prize, a Wallace Stegner Fellowship in Creative Writing from Stanford University, and scholarships from the Tin House and Bread Loaf writing workshops. Her poems and essays have appeared in Tin House, The Believer, New England Review, Narrative, Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. She is an assistant professor at the University of Southern Indiana.

FOUR POEMS by Rosalie Moffett

READ THE PAIRED INTERVIEW WITH ROSALIE MOFFETT

IN SOUND MIND

A jet drags its noise

across my side of town, trawling

for something. Its shadow,

a small black insect, crawls

across house after house. Up and up, over

and over, a lithe little dark thought. I, too

have had a weeviling-through, my sunny

sensibility bedeviled by a pest. Up there, sky-high,

do you, as you go, know the feeling

you slough? Here, when you heft a sack

of flour and watch it cough

into the air one brown moth,

is your knee-jerk reaction Finally!

Some honesty! A thought can worm

and worm its own tangle of unseen tunnel

in the mind for years before things begin

to collapse. Before a word is allowed

out, flapping towards a lamp. Those dummies,

given the rotten meat up-teeming

with maggots, assumed spontaneous generation.

Now we know: flies. Humming thing aloft

in the air. Something descending

to seed a swarm of drear: what

even is the point or so what or what

have you: ruinous little voice-over. I drown

it out however I can. Once, I resorted

to a colander, accidentally fluffed

up a cloud as I sifted mealworms

from flour. Are you, like me, uneasy

with ruin? Do you feel a pity for the blue

your jet plane rakes through, or for me,

whose single-edition sky is getting striped

with white scrapes? Listen, I need to stop

making up gods to talk to

who can’t hear me. Sorry for conjuring you

too aloof, earmuffed and far—

I don’t know how else to be

authentic to my experience. Forgive

me my mind’s circumscribed

design of you, made quick in the shadow

of a small, harmless darkness. Sometimes

one bleak thought breeds in the mind.

No one actually knows, I was shocked

to learn, why moths spiral

towards artificial light—perhaps

they are making

the same mistake as me, desiring

just one moment to speak with

what ruins them.

ODE TO JESSICA

For Jessica Farquhar

If you’re ever in trouble,

find a mother, said Jessica

to her child, refreshing

my predilection for animal videos

where one is raising another’s young,

e.g. the cat with kittens

plus a duckling & the voice

behind the camera announcing

in wonder: it arrived right as she gave birth, like,

get the timing right, a mother

will mother anything. Like,

flip the floodlight & everything

lit up is up for nurturing. Thousands of videos

like this, I swear, exist, inadvertently or deliberately

buttressing her advice in a world

where it’s unwise

to find a policeman or CEO or comedian

or president. America’s

fertility rate is down, the daunt

of saving enough to stave off

progeny-debt is enough

to stall even the reckless.

I’ve a dim view, but it’s true

my brain’s been re-routing frustration

and bungling through a process