EXCERPT FROM THE HISTORY OF LITERACY by K-Ming Chang

Smaller Uncle claimed he could predict a flood was coming when all his nose-hairs swooned and sprinkled the sink. A long time ago, before he washed cars, he used to be a weatherman, which I thought meant he could manufacture weather, plucking out strands of his own hair to double as lightning, the way the Monkey King scattered stalks of his hair to multiply himself, but Medium Aunt told me that actually, it just meant he used to stand in front of a cardboard cut-out sun and guess what time the sky would arrive. My uncle got fired for making a lot of shit up, she explained, like one time predicting a rain of crab claws, and of course everyone was very upset about that because crab claws are delicious and they were all waiting for that day with their pots full of boiling water to catch them. Smaller Uncle interrupted and said, I didn’t mean it would rain literal crab claws, I said that the raindrops would be as large as crab claws, and they’d latch onto you and twist out the meat of your palms, and besides, in the end it didn’t even rain any size and everyone blamed me. That’s nothing, Medium Aunt said, the real scam he pulled is that he can’t even read. The channel was local and there wasn’t a teleprompter or anything, just this guy smoking and holding up pieces of cardboard with the script on it, and your uncle would just make up the script, saying shit like, Tomorrow is sunny with a chance of getting stabbed, likely there will be a night, and all this week there will be sporadic skies soiling themselves. It will be cooler under the shade, so grow some trees. It won’t rain unless you have a leak.

In the sofa bed I shared with my Smaller Uncle and Medium Aunt, I was pocketed between them like a switchblade. In bed, Smaller Uncle laughed so hard at his own made-up weather predictions that the whole apartment rattled like a broken jaw. We fell to the ground, and Uncle rolled me under the sofa bed and said, I forecast it is now earthquaking. Seek shelter beneath your nearest niece. His laughter could even dislocate the building like a shoulder, shifting it half a block up the street, and no one could predict it. Sometimes he would just look at our walls and laugh, and when I asked him what he was laughing at, he said he was reading the mold. It’s making fun of me, he said. There was mold on the wall in the shape of a mouth, and he claimed he could read its lips, claimed he could order the ants on our ceiling to arrange a single sentence. Okay, then what are they saying, I asked. They’re saying you should stop smashing us into sesame paste with your fingers and let us be fluent in foraging, he said. Fine, tell them I don’t like them crawling into my mouth when I’m asleep, I said back. Smaller Uncle shut his eyes, sketched lines in the air with a single finger. Okay, he said, I wrote back to them, but just know that they enter your mouth at night so that you’ll have words to speak in the morning. You think we make words ourselves? We borrow their bodies to speak. That’s nice of them, I said, but still taped my own mouth shut at night, laying strips of tape sticky-side-up around the bed. I asked Medium Aunt if she thought tonight would rain, and she said, I hope not, our ceiling doesn’t even hold up against the dark, look how tomorrow’s leaked in. The mold will multiply into men and then where will we go, she said.

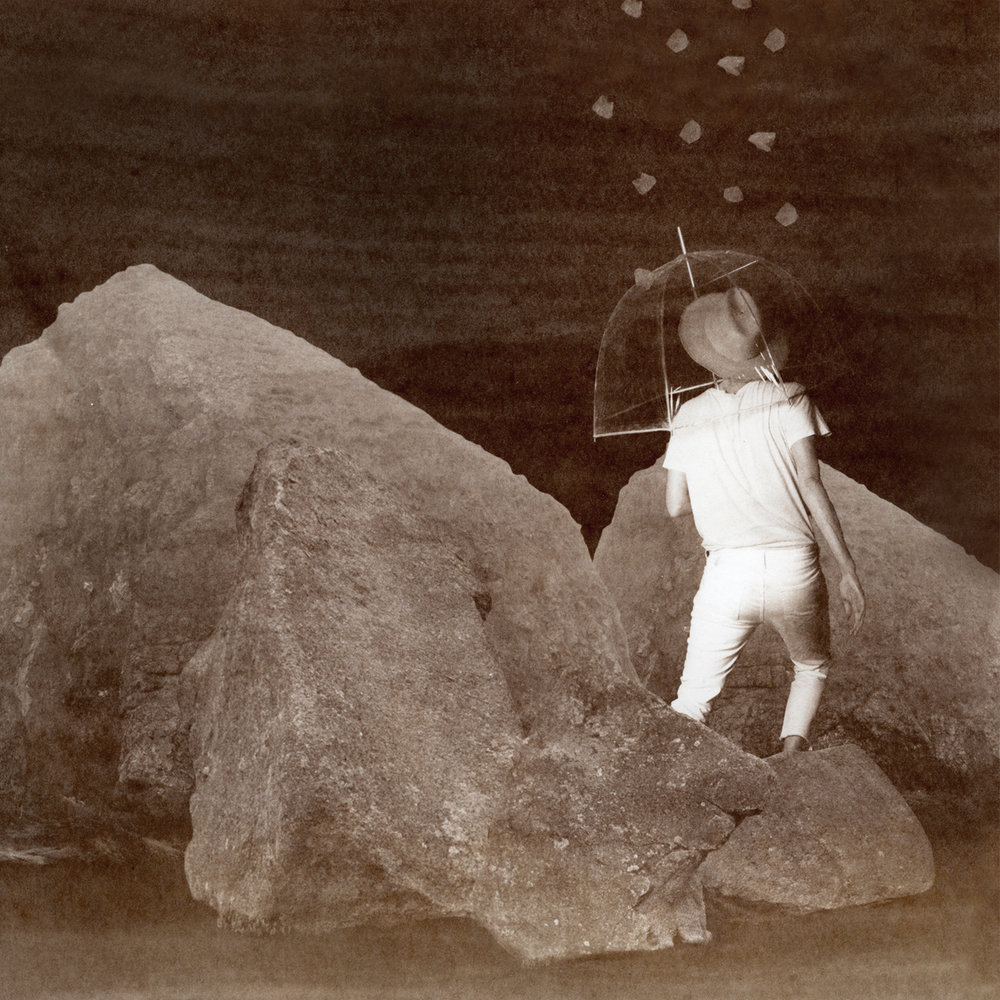

That night, Smaller Uncle told me more stories about the extreme weather incidents he lied about, how he invented local locust plagues, volcanic eruptions, and the impending extinction of the sea. He claimed the sun was a severed head. He said the people of Rudong County believed him so thoroughly that they removed their roofs the day he predicted a hail of pearls. Stop laughing, I told him, I don’t want the city to get a splinter tonight. Okay, he said, and told me another story. About a man named Cangjie who had four eyes. All four were the size of pearl onions in a cocktail of light. This was a long time ago, he said, back when the moon was square, before they realized that light with corners caused accidental eye-gouging when you looked at the moon. One night, the emperor told Cangjie that all across the kingdom, people were rioting against knots. Knots were the only form of writing, and it was beginning to progress into weaponry. Nooses and handcuffs and hogties. So the emperor begged Cangjie to find an alternative. The alternative to a knot is a knife, I said, and the emperor sounds like an idiot. Smaller Uncle smiled and said, I’ll have to decapitate you for disrespect. Listen. Cangjie sat beside a river, but all day it spoke nothing to him. He sat in the mud, but it had no tongue, only stones that settled into the crack of his ass. I told Smaller Uncle that this story was slow, and he said, wait for me to make up the weather. Up in the sky, a crow flew by and dropped a hoofbone at Cangjie’s feet, but he couldn’t read what species the print belonged to. He consulted hunters all over the kingdom, and one finally told him that it was the hoofprint of a pixiu, a species that stomachs gold. Cangjie copied its shape on the sole of his foot and stepped onto a scroll. And that, Smaller Uncle said, was the first written word. I told him the story had holes, like who was the hunter, and why was the bird holding the severed hoof of a pixiu, how did it know where to drop it, and where was the pixiu going, and what did gold have to do with rivermud. He was silent, looking at the ceiling again, and I wondered what he read in those cracks that chronicled our lives, those ruts filled with our blood. You see, he said, a word is just the shape something makes when it falls. Rain too. I imagined the transcription of my feet in mud, how deep a word I would be.

Open your mouth, he said, listen to the leaks saying there’s rain coming. He opened his mouth, and inside I saw the larvae of a language, clung to the roof of him, clusters of light inside. I opened my mouth too, stretching it wide, and waited all night with him. But there was no rain, and in the morning, when I turned my head toward my uncle, he was asleep with his mouth already shut. Medium Aunt was awake in the kitchen, backlit by the TV screen. I kept my mouth open until Smaller Uncle rolled over and told me I could close it finally, that he was wrong after all. In the kitchen, we sat cross-legged on the floor and watched our dumpster-dive TV, which could no longer speak after Smaller Uncle accidentally kicked it over one night when he was drunk. It also meant that some of the faces went missing, and so we identified actors by their shoulders or shadows. After the sound surrendered, Medium Aunt kept the subtitles permanently turned on, and we took turns reading them aloud. Smaller Uncle was silent when we did this, turning his head to the wall, so we pretended to read them aloud just for ourselves, saying the lines like we were repeating them out of shock, like wow, that can’t be true, that there was traffic today, that the clouds came by wind, that the concubine was going to bury the other concubine’s baby alive, that the drought would last for another two hundred years at least, that a fire was furring the sky, that a new species of fish had been found and it used four pairs of eyes, and Smaller Uncle lowered his head and pretended not to listen, sitting cross-legged on the sheets of newspaper we spread on the floor before every meal, the headlines rubbed blank by our knees. He stared at the moldy wall, even after we turned off the TV, sitting still for the ants collaring his neck and stampeding down his spine. I opened my mouth to recite the newspaper headlines swarming around his legs, but he shushed me and said he could do it himself. He told me that all he had to do was sit like Cangjie did, waiting for something to fall, to mean something in the mud. All you have to do is look long enough at something you wanna say aloud, such as the sky, he said. Tomorrow I’ll write you into it.