INTERVIEW WITH K-Ming Chang

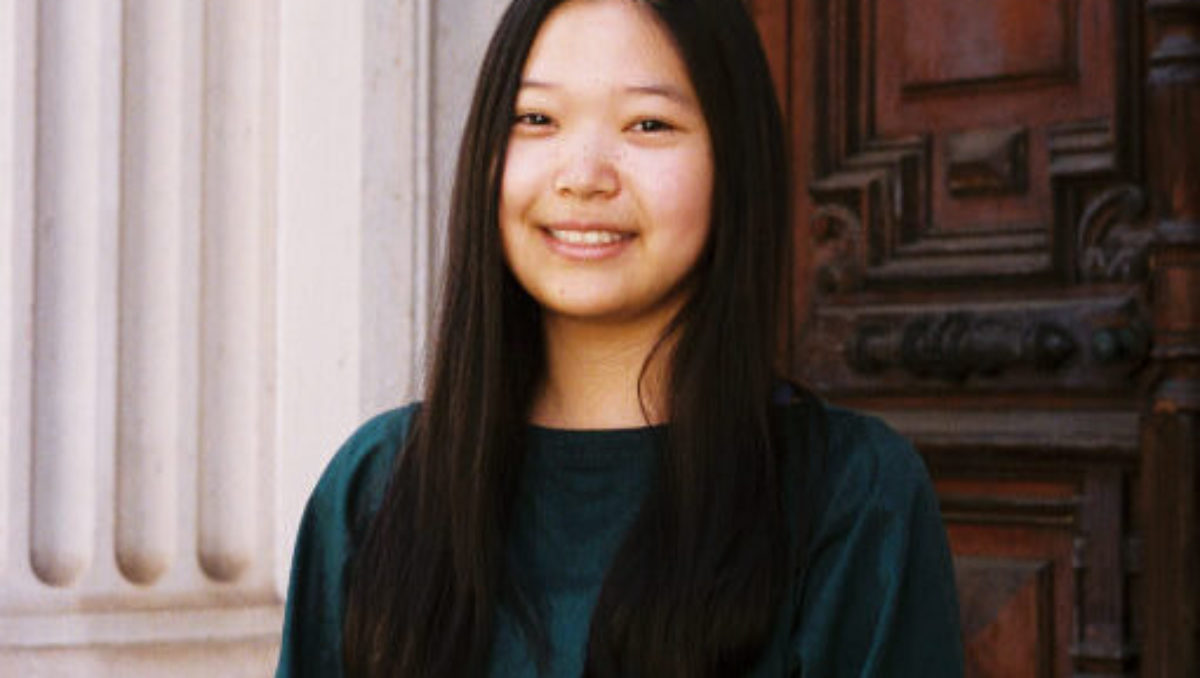

I first read K-Ming Chang’s writing in 2018, back when I was Fiction Editor of Nashville Review. Her story, “Meals for Mourners/兄弟”, captured my attention with its embodied, elemental language and stirring portrait of family life. Since that time, Chang has written a novel, a chapbook, and a story collection, among other projects. Currently, she is a Kundiman fellow. Her story, “Excerpt from the History of Literacy”, was published by Four Way Review in November 2020. While Chang’s characters bite, use meat grinders as weapons, and store their toes in a tin, Chang herself is generous of spirit, prone to doling out affirmations. During an unseasonably warm day in early spring, we talked about the craft of writing, giant snails, and the magic of making things possible.

-Elena Britos

FWR: Today I thought we could talk about your writing through a craft lens. Craft means different things to different people. To start, writer Matthew Salesses says in his recent book, Craft in the Real World, that “Craft is a set of expectations. Expectations are not universal; they are standardized. But expectations are not a bad thing.” What expectations do you feel you must meet in your writing, and whose expectations are they?

(Chang holds up her own copy of the book excitedly)

KMC: Maybe this is more what expectations I don’t meet, but I never want to explain things [to the reader] I wouldn’t explain to myself. If I were the reader and I wouldn’t need an explanation, then [as the writer,] I’m not giving one, even when I know it could make the reading more difficult for someone else. I write for myself first and foremost. I always use myself as a compass. If I am surprised or delighted by something or laugh at something or understand something, I allow that to be the compass. If I think too much about how a stranger will read it, I lose all sense of how I want the work to be.

FWR: So you’re meeting your own expectations when you write?

KMC: Yes. My expectations for myself are harsh, and I can be self-deprecating toward my own work. So, what I try to do is distance myself from [my work] as much as possible. I try not to think about how this is something I’ve spent a lot of time on and hate. I try to give myself time, a couple months or longer, and come back to the page to experience it as a reader. I look for a sense of surprise, always. I want to think, “Wait, I don’t remember writing this! I didn’t expect it to end there!” If I am not surprised, I know it’s not ready yet.

If I am not surprised, I know it’s not ready yet

FWR: How do you shock yourself when you are the one creating the surprise?

KMC: It does happen! When it goes well, the work ends up really far from where I started. It’s like a game of telephone from the first sentence—it mutates so much. Sometimes the surprise is even just a metaphor, and that can be enough.

FWR: Right now, you edit The Offing’s Micro section, which the journal files under its Cross Genre vertical. When I think of your writing as a body, “cross genre” is kind of the perfect category-defying category for it. It’s like having a non-container. Yet, no matter what form your writing takes, I feel I would recognize a K-Ming Chang piece anywhere. Part of the reason for this is your use of language on a line level. How would you describe your style?

KMC: I love this idea of a non-container! I think my style is very language driven, the idea of letting language lead me rather than logic. This sometimes results in a lot of derailing in my work—like, wow that sounded really interesting, but what does it mean? I find that’s where I have to reign myself in. I am very interested in lineages and mythmaking, creation and destruction, the elemental things that are common in mythical worlds. My style is hard for me to describe because I feel I am always trying to break out of my own style. When I write poetry, I am always trying to break out of my own poetic voice, and when I write prose, I feel very resistant to prose forms and sentences. So, it’s a constant wrestling.

I think my style is very language driven, the idea of letting language lead me rather than logic

FWR: I am always amazed by your ability to work fluidly across genres and forms. You write poetry, short stories, novels, micro fiction, and beyond. You have a poetry chapbook coming out from Bull City Press called Bone House. You also have a forthcoming story collection from One World called Gods of Want. When you sit down to write, do you have the intention to create, say, a short story from the outset? Or do you first have an idea for what your narrative is about, and then select its formal (non-)container?

KMC: I used to think it was a profound process, but it’s really like having a loose thread on your sweater that you yank. Usually, I start with a first sentence or even a few words. And then I pull on it and pull on it and let it expand. Usually what ends up happening is that whatever I think I am writing ends up as a giant block of text. When I think about what kind of narrative it will become—if it is a narrative—that is part of the revision process. When I am in the process of writing and producing, I really have no concept of “is this fiction, is this autobiographical, is this an essay, is this a poem?” That’s a lens for later.

FWR: That shows in your work. It feels like the language almost comes first and then the story blooms in this really interesting, organic way. What was it like writing Bestiary using this process?

KMC: I always joke that I tricked myself into writing it. When I was writing it, I wasn’t thinking, “Oh, this is a novel. This is a full manuscript or project.” I wasn’t thinking anything. I was allowing it to be fragmented, almost like a series of essays, where each section had its own completed arc (which I later unraveled). I wanted to play on the page and have the scope be a bit smaller while I was writing. If I thought, “What is the through-line? What is the plot?” it would have been mentally strenuous, stressful, and scary for me. It was a mind trick. Then later, I unstitched it all and rewrote it.

FWR: When I read Bestiary, I was struck by the density of figurative language and how you use proverbs to explain the world. For example, “the moon wasn’t whitened in a day” and “burial is a beginning: To grow anything you must first dig a grave for its seed.” For me, these aphorisms are a kind of hand off into the myth and magic in your stories. You explain the world through the earth, through the body, through transformation. Your characters do not only feel that they have sandstorms in their bellies when they are sick—they literally have sandstorms in their bellies. Can you talk about the connection between language and transformation in your stories?

KMC: Wow that is so beautiful and profound! I think transformation is the perfect word. In a lot of ways, it is like casting a spell with language. Through metaphor, you turn something into something else. In the language, that is the reality. I had a teacher named Rattawut Lapcharoensap who wrote a story collection called Sightseeing. He told me that writing makes something possible that wasn’t possible before. I love that definition of writing—to make something possible. It is also very literal. You take a blank page and put words on it that weren’t there before. If you think about it that way, it isn’t so profound, but there is something magical about it to me. Regarding proverb and myth, I love that language can be embodied. Language isn’t just a passive tool to render something. The poet Natalie Diaz once gave a talk at my school, and she said in the alphabet, the letter A came from the skull of an animal, and that’s the etymology of the letter A.

FWR: I feel like you wrote that! Speaking of real histories embodied in language, many of your stories are metafictional. In your short story “Excerpt from the History of Literacy,” your novel Bestiary, and your forthcoming chapbook Bone House, you use myths, wives’ tales, epistolary, oral storytelling, and Wuthering Heights to inform your narratives. In your mind, what is the role of the metafiction for the plot at hand? How do other stories inform what is happening in your own work?

KMC: I love that you asked about metafiction because I’ve actually been thinking about this. It’s interesting because when people think metafiction, they think postmodern. They think that it’s a very recent thing to have moments of meta in fiction. Chinese literature is extremely metafictional. The beginnings of chapters will say, “In this chapter, here’s what you’re going to learn.” And then at the end of the chapter they’ll say, “to find out the end of this conflict, read on to the next chapter.” In a lot of translated Chinese fiction that I know and love, there’s this sense of artifice. I am constructing something for you, so read on to the next chapter, the next scaffolding. It shows you the performance of the fiction, which I love so dearly. It’s ancient, not experimental or new or strange—maybe it is to Western audiences. Regarding plot, I think there’s something very playful about reminding the reader of the fiction. It kind of breaks the expectation of realism, which opens up the possibilities—this is all a construct anyway, so why can’t you give birth to a goose? Why can’t you fly?

Regarding plot, I think there’s something very playful about reminding the reader of the fiction. It kind of breaks the expectation of realism, which opens up the possibilities—this is all a construct anyway, so why can’t you give birth to a goose? Why can’t you fly?

FWR: Earlier, you mentioned you write to fulfill your own expectations. In her lecture titled “That Crafty Feeling”, Zadie Smith says that critics and academics tend to explain the craft of writing (or, expectations) only once a text has been written—that is, after the fact of making. She says that “craft” is almost retrospective. It doesn’t really tell a writer how to go about writing, say, a novel. Does this resonate with you?

KMC: I completely agree! There are so many times where I’ve only been able to articulate my intentions, or what tools I’ve used to articulate those intentions, long after I’ve written the thing. Most of the time I don’t even know my own motivations, much less my own expectations, for writing a particular piece. I think that’s part of the joy and mystery of the experience – if I clearly know my own expectations and how I’m going to fulfill them, it tends to fizzle out quickly. There’s something about being a perpetual beginner, or at least feeling like one, that makes writing possible for me.

FWR: Have there been times when you’ve been given craft advice you refused to heed? What writerly hills have you died on? You’ve been lovely to work with from an editorial standpoint, but I wonder if there are times you feel the need to put your foot down.

KMC: I love getting edits and feedback because I’m constantly lost in the woods. I’m always asking what to cut—I welcome it! But I think I struggle with conventions of storytelling that we get told as writers. We internalize things like, “Make sure the narrator is driving the story and have an active narrator.” I’m really curious about stories that have characters who are caught in the eye of a storm—who are not necessarily driving the story, but are in circumstances where the world is what is moving them, because of status and who they are! This idea of an “I” narrator who creates conflict and action is a very particular way of seeing yourself in relation to the world that I don’t think my narrators have the privilege to experience. I have also been told, “Every word is necessary”—to have an economy of language. There’s an interview with Jenny Zhang in the Asian American Writers Workshop where she says, “I don’t want to be economical. I want to be wasteful with language.” I loved it so much I wrote it down. I fight against this utilitarian idea. Write toward the delight of sounds and words. Why follow this capitalist directive in the way that we write? I think breaking out of that is really important.

I fight against this utilitarian idea. Write toward the delight of sounds and words. Why follow this capitalist directive in the way that we write? I think breaking out of that is really important.

FWR: I like the idea of being wasteful with language. I think you could also see it as being generous with language.

KMC: Yes.

FWR: You talk about your characters not being as active. How do you go about developing your characters? I’m thinking about how Smaller Uncle in “Excerpt from the History of Literacy” is most vivid in relation to the details assigned to him—from the tendencies of his nose hairs to the way he fixes the “dumpster-dive TV.” Can you talk more about how you develop and discover your characters?

KMC: A specific phrase or voice will pop into my head and I’m like, “Who is this? Who are you? Why would you say this?” It’s always horror or shock at some terrible thought. It always comes from this place of curiosity. I want to know why this person is thinking this or doing this in a particular moment. The unravelling is discovering what happens. I sometimes stray completely from where I began, but character is really the driving force of my curiosity. I want to find out the circumstances under which characters do or say certain things. We often think that characters need to have individualistic, unique, instantly recognizable identities. But I’m really interested in collectives. People whose selfhood bleeds into their families and their communities, with lovers. I love the mutability of the self. I’m more interested in how selfhood doesn’t exist—the blurring of borders.

But I’m really interested in collectives. People whose selfhood bleeds into their families and their communities, with lovers. I love the mutability of the self. I’m more interested in how selfhood doesn’t exist—the blurring of borders.

FWR: Do you have any favorite literary characters?

KMC: In Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen, there is a character called Moonie. The book begins as a revenge story, and I love revenge. I love this character and this book! I also have a huge weakness for Wuthering Heights. I am endlessly fascinated by any character from Wuthering Heights. I may not ever want to meet them or interact with them, but I have endless fascination. There are so many mythical characters I love from different mythologies. There is a snake goddess who is also a giant snail sometimes. I’m delighted that she’s a giant snail. Yes, I love that. Her myth is that she creates the world and creates people out of mud. We’re all just snails!

FWR: I’ve always felt that way. So, what are you reading right now?

KMC: I’m rereading a book that’s coming out in July from my publisher, One World, called Ghost Forest by Pik-Shuen Fung. I also just read a book called Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge. It’s coming out from Melville House and is one of my favorite books of all time. The myth, the uncanniness, the strange beasts—I feel like the title is self-explanatory. It broke me out in a cold sweat the whole time, but in the best way. I have this goal for myself that will probably never happen to read all four classic novels of China. One of them is Dream of the Red Chamber, which I have read, and Water Margin, which is about bandits. I love writing about pirates and I feel like bandits are of the same branch, so I want to start reading that.

FWR: Thanks for the recs! Before you go—any thoughts on the pandemic’s impact on your writing?

KMC: In terms of the actually sitting down and writing, not much has changed. For me, there is an increased sense of urgency in wanting to tell certain stories that are in a community. Before Covid, my stories were about interwoven webs of community. That’s very important to me, and this was heightened during the pandemic. Part of that is because I spent a lot of time with my family in the hustle and bustle of a very large household. I remembered what it was like to be surrounded by voices and storytellers all the time. Being home rerouted me in what I wanted to do. Being solitary helps me write, though. I try to create that solitude. When I was living at home, I had this habit of writing in ungodly hours of the night. At first, I thought it was because I am such a night owl, but really, it’s because I was alone. When everyone in the house was either out or sleeping, everything was muted. The windows were so black I couldn’t see out into the world. I felt so alone, and it almost created my mood. I needed to enter that space to be with myself. I needed the solitude of night pressing in.

- Published in Featured Fiction, home, Interview, Monthly

EXCERPT FROM THE HISTORY OF LITERACY by K-Ming Chang

Smaller Uncle claimed he could predict a flood was coming when all his nose-hairs swooned and sprinkled the sink. A long time ago, before he washed cars, he used to be a weatherman, which I thought meant he could manufacture weather, plucking out strands of his own hair to double as lightning, the way the Monkey King scattered stalks of his hair to multiply himself, but Medium Aunt told me that actually, it just meant he used to stand in front of a cardboard cut-out sun and guess what time the sky would arrive. My uncle got fired for making a lot of shit up, she explained, like one time predicting a rain of crab claws, and of course everyone was very upset about that because crab claws are delicious and they were all waiting for that day with their pots full of boiling water to catch them. Smaller Uncle interrupted and said, I didn’t mean it would rain literal crab claws, I said that the raindrops would be as large as crab claws, and they’d latch onto you and twist out the meat of your palms, and besides, in the end it didn’t even rain any size and everyone blamed me. That’s nothing, Medium Aunt said, the real scam he pulled is that he can’t even read. The channel was local and there wasn’t a teleprompter or anything, just this guy smoking and holding up pieces of cardboard with the script on it, and your uncle would just make up the script, saying shit like, Tomorrow is sunny with a chance of getting stabbed, likely there will be a night, and all this week there will be sporadic skies soiling themselves. It will be cooler under the shade, so grow some trees. It won’t rain unless you have a leak.

In the sofa bed I shared with my Smaller Uncle and Medium Aunt, I was pocketed between them like a switchblade. In bed, Smaller Uncle laughed so hard at his own made-up weather predictions that the whole apartment rattled like a broken jaw. We fell to the ground, and Uncle rolled me under the sofa bed and said, I forecast it is now earthquaking. Seek shelter beneath your nearest niece. His laughter could even dislocate the building like a shoulder, shifting it half a block up the street, and no one could predict it. Sometimes he would just look at our walls and laugh, and when I asked him what he was laughing at, he said he was reading the mold. It’s making fun of me, he said. There was mold on the wall in the shape of a mouth, and he claimed he could read its lips, claimed he could order the ants on our ceiling to arrange a single sentence. Okay, then what are they saying, I asked. They’re saying you should stop smashing us into sesame paste with your fingers and let us be fluent in foraging, he said. Fine, tell them I don’t like them crawling into my mouth when I’m asleep, I said back. Smaller Uncle shut his eyes, sketched lines in the air with a single finger. Okay, he said, I wrote back to them, but just know that they enter your mouth at night so that you’ll have words to speak in the morning. You think we make words ourselves? We borrow their bodies to speak. That’s nice of them, I said, but still taped my own mouth shut at night, laying strips of tape sticky-side-up around the bed. I asked Medium Aunt if she thought tonight would rain, and she said, I hope not, our ceiling doesn’t even hold up against the dark, look how tomorrow’s leaked in. The mold will multiply into men and then where will we go, she said.

That night, Smaller Uncle told me more stories about the extreme weather incidents he lied about, how he invented local locust plagues, volcanic eruptions, and the impending extinction of the sea. He claimed the sun was a severed head. He said the people of Rudong County believed him so thoroughly that they removed their roofs the day he predicted a hail of pearls. Stop laughing, I told him, I don’t want the city to get a splinter tonight. Okay, he said, and told me another story. About a man named Cangjie who had four eyes. All four were the size of pearl onions in a cocktail of light. This was a long time ago, he said, back when the moon was square, before they realized that light with corners caused accidental eye-gouging when you looked at the moon. One night, the emperor told Cangjie that all across the kingdom, people were rioting against knots. Knots were the only form of writing, and it was beginning to progress into weaponry. Nooses and handcuffs and hogties. So the emperor begged Cangjie to find an alternative. The alternative to a knot is a knife, I said, and the emperor sounds like an idiot. Smaller Uncle smiled and said, I’ll have to decapitate you for disrespect. Listen. Cangjie sat beside a river, but all day it spoke nothing to him. He sat in the mud, but it had no tongue, only stones that settled into the crack of his ass. I told Smaller Uncle that this story was slow, and he said, wait for me to make up the weather. Up in the sky, a crow flew by and dropped a hoofbone at Cangjie’s feet, but he couldn’t read what species the print belonged to. He consulted hunters all over the kingdom, and one finally told him that it was the hoofprint of a pixiu, a species that stomachs gold. Cangjie copied its shape on the sole of his foot and stepped onto a scroll. And that, Smaller Uncle said, was the first written word. I told him the story had holes, like who was the hunter, and why was the bird holding the severed hoof of a pixiu, how did it know where to drop it, and where was the pixiu going, and what did gold have to do with rivermud. He was silent, looking at the ceiling again, and I wondered what he read in those cracks that chronicled our lives, those ruts filled with our blood. You see, he said, a word is just the shape something makes when it falls. Rain too. I imagined the transcription of my feet in mud, how deep a word I would be.

Open your mouth, he said, listen to the leaks saying there’s rain coming. He opened his mouth, and inside I saw the larvae of a language, clung to the roof of him, clusters of light inside. I opened my mouth too, stretching it wide, and waited all night with him. But there was no rain, and in the morning, when I turned my head toward my uncle, he was asleep with his mouth already shut. Medium Aunt was awake in the kitchen, backlit by the TV screen. I kept my mouth open until Smaller Uncle rolled over and told me I could close it finally, that he was wrong after all. In the kitchen, we sat cross-legged on the floor and watched our dumpster-dive TV, which could no longer speak after Smaller Uncle accidentally kicked it over one night when he was drunk. It also meant that some of the faces went missing, and so we identified actors by their shoulders or shadows. After the sound surrendered, Medium Aunt kept the subtitles permanently turned on, and we took turns reading them aloud. Smaller Uncle was silent when we did this, turning his head to the wall, so we pretended to read them aloud just for ourselves, saying the lines like we were repeating them out of shock, like wow, that can’t be true, that there was traffic today, that the clouds came by wind, that the concubine was going to bury the other concubine’s baby alive, that the drought would last for another two hundred years at least, that a fire was furring the sky, that a new species of fish had been found and it used four pairs of eyes, and Smaller Uncle lowered his head and pretended not to listen, sitting cross-legged on the sheets of newspaper we spread on the floor before every meal, the headlines rubbed blank by our knees. He stared at the moldy wall, even after we turned off the TV, sitting still for the ants collaring his neck and stampeding down his spine. I opened my mouth to recite the newspaper headlines swarming around his legs, but he shushed me and said he could do it himself. He told me that all he had to do was sit like Cangjie did, waiting for something to fall, to mean something in the mud. All you have to do is look long enough at something you wanna say aloud, such as the sky, he said. Tomorrow I’ll write you into it.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized