MONTHLY WITH Rosalie Moffett

FOUR POEMS

INTERVIEW

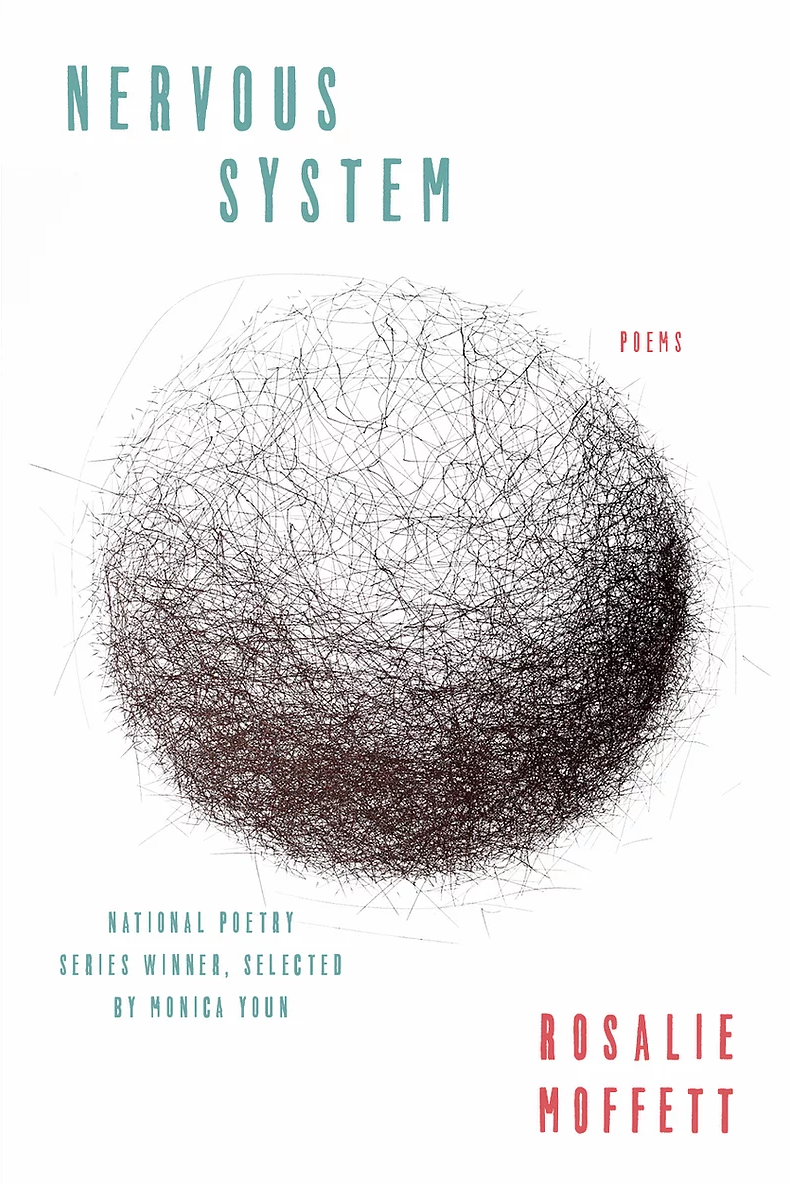

Rosalie Moffett is the author of Nervous System (Ecco) which was chosen by Monica Youn for the National Poetry Series Prize, and listed by the New York Times as a New and Notable book. She is also the author of June in Eden (OSU Press). She has been awarded the “Discovery”/Boston Review prize, a Wallace Stegner Fellowship in Creative Writing from Stanford University, and scholarships from the Tin House and Bread Loaf writing workshops. Her poems and essays have appeared in Tin House, The Believer, New England Review, Narrative, Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. She is an assistant professor at the University of Southern Indiana.

FOUR POEMS by Rosalie Moffett

READ THE PAIRED INTERVIEW WITH ROSALIE MOFFETT

IN SOUND MIND

A jet drags its noise

across my side of town, trawling

for something. Its shadow,

a small black insect, crawls

across house after house. Up and up, over

and over, a lithe little dark thought. I, too

have had a weeviling-through, my sunny

sensibility bedeviled by a pest. Up there, sky-high,

do you, as you go, know the feeling

you slough? Here, when you heft a sack

of flour and watch it cough

into the air one brown moth,

is your knee-jerk reaction Finally!

Some honesty! A thought can worm

and worm its own tangle of unseen tunnel

in the mind for years before things begin

to collapse. Before a word is allowed

out, flapping towards a lamp. Those dummies,

given the rotten meat up-teeming

with maggots, assumed spontaneous generation.

Now we know: flies. Humming thing aloft

in the air. Something descending

to seed a swarm of drear: what

even is the point or so what or what

have you: ruinous little voice-over. I drown

it out however I can. Once, I resorted

to a colander, accidentally fluffed

up a cloud as I sifted mealworms

from flour. Are you, like me, uneasy

with ruin? Do you feel a pity for the blue

your jet plane rakes through, or for me,

whose single-edition sky is getting striped

with white scrapes? Listen, I need to stop

making up gods to talk to

who can’t hear me. Sorry for conjuring you

too aloof, earmuffed and far—

I don’t know how else to be

authentic to my experience. Forgive

me my mind’s circumscribed

design of you, made quick in the shadow

of a small, harmless darkness. Sometimes

one bleak thought breeds in the mind.

No one actually knows, I was shocked

to learn, why moths spiral

towards artificial light—perhaps

they are making

the same mistake as me, desiring

just one moment to speak with

what ruins them.

ODE TO JESSICA

For Jessica Farquhar

If you’re ever in trouble,

find a mother, said Jessica

to her child, refreshing

my predilection for animal videos

where one is raising another’s young,

e.g. the cat with kittens

plus a duckling & the voice

behind the camera announcing

in wonder: it arrived right as she gave birth, like,

get the timing right, a mother

will mother anything. Like,

flip the floodlight & everything

lit up is up for nurturing. Thousands of videos

like this, I swear, exist, inadvertently or deliberately

buttressing her advice in a world

where it’s unwise

to find a policeman or CEO or comedian

or president. America’s

fertility rate is down, the daunt

of saving enough to stave off

progeny-debt is enough

to stall even the reckless.

I’ve a dim view, but it’s true

my brain’s been re-routing frustration

and bungling through a process

that, magic-8-ball-like, produces

the solution: have a baby. Little wailing

thing. When feeling low, I scroll

through online lists of expenses

for the first year of life. It never fails

to make everything worse.

Once, I read an article

about a woman who joined

a search party searching for her. For hours,

she looked for herself.

I am supposed to be finding a mother.

I’m staring at the blank in my bank balance.

God knows the best prayers

one can say in America are to the patron saints

of student debt, of Ca$h for Gold,

of the lowest of the low

deductibles. Oh, God knows

I know the last thing

the world needs is more

people, it’s so full up with policemen,

gun nuts, florists, pundits, artists,

landfills, Jessica, kneeling

face-level with her son, Jessicas

ready to kneel face-level

with anyone’s son.

TAXES, ICECAPS, CROCUSES

In the bank account, it is

unseasonably mild. The businessmen

who live there rarely break

a sweat, whereas it is, elsewhere,

unseasonably disastrous. Wildfire.

Flooding. Diseases unreasonably

rising up, little ghosties, from

the permafrost melt. It is everything

anyone talks about, though the seasoned

businessmen never go anywhere

near the copier, the water-cooler, the arenas

of anyone. Meticulous, they maintain

their distance and their coin

-colored comb overs coiffed into hieroglyphs

of I’ll be dead before any of this

shit hits the fan. By many accounts, an account

is a story, and thus money is a moral

available solely to an upper crust mostly

into fan fiction: Goodnight moon. Goodnight

congressman. Sayonara taxes,

icecaps, crocuses. The bank account can be

summoned by the right spell of two

point authentication—presto: see the men

gazing through the boardroom

window at the view, which is the mountainous

horizon, which is a jagged line graph.

X-axis: months. Y-axis: the accrual

of funds. In the bank account,

there’s a potted plastic palm whose leaves

shift in the manner of blades catching light

in a knife-fight. The businessmen take

solace in the view, they take

turns watering the palm, they take money

and turn back to the window. They keep

the money. They keep watering. Water outside keeps

rising. Inside there’s a weird black spot

developing on the carpet. They were told it was there

to give them a sense of the exterior world.

They were informed that it was, for their safety

decorative. This was about the palm

whose faux trunk pokes down into styrofoam.

But in the bank account, they don’t listen, which is

corporate policy, which is for their safety

and to maintain their equilibrium in case

a message weasels in from the gate

intercom re: some faulty product, some leaky

lifeboat in the polar ice cap

melt. Despite that, and also though

they were sure they’d made, as young men,

strict provisions against such an act,

they were beguiled

by the idea that they might

nurture one quiet thing. They keep

watering. The mold loves the moisture, the micro-

fiber playground, it throws its personal confetti

of deadly spores. Even now, it advances

over the carpet, army-crawling

towards the loafers with the slit at the toe

where, tucked, is a hundred dollar bill. Suppose

this is a fable. Moreover, suppose there is a moral

to be made from the world

anyone can imagine, a lesson, a hinge

between it and the inside

of the mind. Suppose you entertain

this idea for your own comfort

in the manner of tending

to the kind of plant that, turns

out, grows more and more

suspect the longer

it neither blooms nor fruits.

NEST EGG

Logging in to check the pie graph

of one’s 401K: boring miserly pastime

of the 21st century. No lovely clunk

of a gold doubloon, just Scrooge

and his TIAA CREFF password.

Just Scrooge McDuck and his new bird-body.

My first time in Georgia it was August

& I was aghast at the snow

floating in the blue sky. (Hide your eyes,

McDuck, each time we find ourselves

driving in the wake of a chicken truck.)

Point is, most miracles

can be pinned on other people

amassing money in offshore accounts.

Once, I saw rocks light up on the bank

as the surf crashed in: true phenomenon

of phosphorescent plankton. Once, the power

went out in a packed stadium,

and the ring of stands fired up with that exact

blue-white plankton-light from flipped

open flip phones. From above, there must’ve been

one shining eye in the pitch black

of the rest of Dakar. The pie graph

is a joke: it shows only what you have now

as if that’s enough to illuminate enough

of a patch of the quiet dark

of the future. Ah, Scrooge, I know

the balm of a tall stack of coins. I, like you,

have a nest of fear. I like you best

as a bird. I read how domestic ducks

neglect their eggs, which must be

electrically incubated. Warm bulb which nursed

current from the wall-socket to make you

take form, made you take all the currency & hold it

to the light to see if it could be changed

from coin to mirror, from mirror to periscope

to peer into the unknown. Ah, Scrooge, it feels

like it works, doesn’t it? You were the first

duck to dip your spatz into an olympic pool

of money—even as you dove, even as the children

rubbed, in disbelief, their fists across the dollar signs

in their eyes, someone watched

the scales shift, felt the digits of the budget

loosen their chokehold.

- Published in Monthly, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Rosalie Moffett

READ THE POEMS PAIRED WITH THIS INTERVIEW

FWR: In my first read of “In Sound Mind”, I was struck by how you play with sound throughout the poem (such as the lines “Up there, sky-high,/ do you, as you go, know the feeling/ you slough?”). Can you speak about the growth of this poem? How does consonance (and dissonance!) influence your process– if at all?

Rosalie Moffett: I think I’ve been gravitating towards letting sound lead the way during this particular political period, and this pandemic—I’ve been angry, sad and with something overly simple to say stuck in my craw. Which makes a boring poem. A hallway you can see the end of from the beginning. But to let sound in as a guide gives that hallway some doors, some new avenues. There are then things behind doors that I have to shift in order to see. It opens rooms in my thoughts I didn’t know were there. Which certainly happened in this poem.

And (if you forgive me my wandering into some more conjectural territory) back in high school when I was obsessed with the weird experiments conducted in service of psychology and sociology, I remember learning about cognitive dissonance. In one study, participants were asked to either hold a pencil by pursing their lips, or in their teeth, like a rose. Rough approximations of a frown and a grin. They were then told jokes. Those with the pencil in their teeth found the jokes funnier. In short, the brain said “I must think these are funny, I’m smiling.” The brain likes to follow the body’s lead. Out loud, the mouth makes a rough smile in weeviling, feeling, bedeviled. Makes a rough frown when saying I don’t know, No one knows. I say all this not to claim my poems are smart enough to play these sounds like an emotional piano, but to offer that the sound of a poem might be working on our cognition in ways that are deeply layered and complex. I trust it to lead me through a poem.

FWR: There’s sly humor in these poems, particularly in “Nest Egg” with its addresses to Scrooge McDuck, that carves a new path to the emotional heart of each poem. It serves to buttress the associative leaps you make through the poems and expand on the emotional surprise. How do you see humor in your work?

Moffett: Humor is the PPE gear my mind wears, the way I can make something dark harmless enough to look at. There’s that old chestnut: tragedy + time = comedy. Often, when you’re too close to something, you can’t see the humor in it. If you train yourself to see the comedy, it’s like instant distance. (Instadistance™) You can see how humor could serve as a survival tactic, a jetpack out of actually facing something–and I think there’s a danger of that to be aware of in writing poems. But it’s also, I think, a useful way to gain perspective. Make something funny, and you can look down at it as if from a great height. What is also true is that this training (if you’ll let me call it that) makes a 2-way street. You can zoom in and see the tragic in something that, at first, seems funny. Scrooge McDuck? A duck obsessed with something he can’t eat? Swimming in coins? Oh, honey. What have we made.

Some of my zooming-in involves digging into granular and aspects of things populating my poems. Little of my “research” ends up in the poem (and I defy any algorithm to make sense of my internet searches). For this poem, I did a lot of reading about the character of Scrooge McDuck (yes, his was the first depiction of a swimming pool of money) and got to feel kind of close to him, a kinship. At some point in his history, he changed–someone took pity and shifted him from a miser (clinging to what he couldn’t even make use of) into a philanthropist. I wish that same hand would take pity on me.

FWR: I love your last images, whether Jessica kneeling with “anyone’s son” or the plant that neither “blooms nor fruits”. How do you know when you’ve ‘stuck the landing’ in a poem? Are there poems that you admire for their endings?

Moffett: If only, like in gymnastics, one could look up and see the score from judges!

I think what I look for is that feeling that my mind is standing, so to speak, on a new patch of land. A new vantage point. A poem, uniquely, is a negotiation with white space, with absence. Each line and stanza break are little perches from which to consider that absence. And that last line is where the reader stops, as if at the edge of a cliff, to look out. If there’s something still ringing, something hovering in the mind’s eye, demanding attention, OK. Good.

The cliff came up suddenly in Carrie Fountain’s poem “The Jungle” and then there I was, looking over the edge, ringing.

- Published in Interview, Monthly, Uncategorized