INTERVIEW WITH Stella Lei

Stella Lei is a writer from Pennsylvania and an Editor–in–Chief for The Augment Review. Rhythmic and resonant, her debut prose chapbook, Inheritances of Hunger (River Glass Books, 2022), is a vivid, thrilling collection featuring five stories punctuated by cruelty and intimacy as she interrogates generational hurt through the rawness of hunger and girlhood.

Emily Judkins/Four Way Review: Inheritances of Hunger’s themes of family, specifically mother-daughter relationships, shine throughout this collection, but I particularly love how you embody these themes by exploring hunger’s origins, as well as its consequences. Where did the image of hunger come from while you were writing? Did you find your intention in targeting hunger in its various forms a sustained investigation?

Stella Lei: Thank you so much for asking. When I was writing this [chapbook], I actually came up with the idea of putting these stories together because I had written “Games” and “Changeling,” independently of each other, in a row. Maybe coincidentally. Maybe not. After writing those two stories that focus on hunger and on cruelty and on familial relationships back to back, I noticed a lot of commonalities between them thematically, tonally, and imagery wise. I wanted to dig deeper into why I was so preoccupied with these themes and images and how I might want to continue investigating them. So, after I drafted “Changeling” and started noticing those common threads, I wrote a few bullet points for myself about how I was using hunger in both stories and the role that hunger plays in both stories, both as a physical sensation and as a motif, and the different ways in which these characters interact with their hunger (actively and passively). In that development process, this hunger became a literalization of or an embodiment of hurt and cruelty, asking if these experiences and emotions are inheritable, including the yearning that comes with hunger. I was thinking about how to convey generational hurt and generational violence in an embodied way.

FWR: I definitely felt all those threads being interwoven together. I think the core of the chapbook is so strong that when you experimented within the stories, the main themes remained cohesive and tangible . Once you found this core, how did you then draw upon and tie together these traditions, experiences, previous writings, and other inspirations to fully flesh it out so it could go in so many different directions?

SL: Once I figured out that I wanted to use hunger as a central metaphor/motif throughout this chapbook, I wrote down a lot of different ideas for different directions in which this hunger could go. I tried to approach these ideas of abuse and of generational violence and of complicated families in slightly different ways. For example, in “Graftings,” the familial structures get complicated because we have this mother who is very neglectful and the sister, in turn, has to take the place of the mother, versus how in “On Building a Nest,” the mother has trapped the daughter in this flawed ideology as a way of keeping the daughter dependent on her. These different dynamics play out across similar themes. As for inspirations from other sources, “Changeling” was very much directly inspired by Ren Hong’s photography, and from there I started looking into more contemporary Chinese photography. There’s a certain atmosphere to those works that I really love and that became sort of central to how I developed the atmosphere of the chapbook, even if it might not be explicitly related.

FWR: Yeah, totally! The atmosphere throughout the chapbook is so stellar and well defined. I think part of that is thanks to how you have so many different details, as well as the intuition of knowing when to pull back on them. I’m thinking about the two characters in “Games” and how their relationship isn’t really defined — they don’t even have names — yet they feel incredibly real and I personally found them recontextualized while reading more of Inheritances. I had inferred that the characters were sisters based on the other strong sister relationships in the chapbook and how these relationships can be obscured due to trauma and familial situations, such as in “Graftings” where, as you were saying, Elaine takes on this maternal role for Charity due to neglect. Could you talk about how you know when to pull back on details and obscure certain characterizations to allow more possibilities?

SL: One thing I tried to do in writing and finding the balance between details and obscurity is letting these characters and their relationships speak for themselves, rather than putting down hard definitions for who these people are and how they have shaped each other. By letting their actions and subtext speak for itself through the selection of specific details, I tried to demonstrate how the cruelty or the hurt or the mutual yearning of these relationships play off of each other and let the reader derive a context from that, especially in “Games.” Like you said, these girls are not named and their relationships are not defined, but there is a very palpable intimacy in that story and intimacy within the violence of what they’re doing and in their own hurt. I think that [intimacy] gives you an on ramp into the other familial relationships in the chapbook and how these stories work together in a community: they provide context and support specific details, while letting the individual relationships speak for themselves, rather than defining them very strictly on the page.

FWR: I love the idea of these stories working within a community, because, since so much of the chapbook is about generational trauma and familial hurt, it’s almost as if these stories became a supportive community for each other.

Focusing on the details and tones throughout the chapbook, I love how you utilize the idiosyncrasies of the characters and settings to really make them come alive. Still talking about “Games,” the two girls are playing knife games as “crabgrass chokes [their] feet” in their backyard, which is a “minefield of wounds” — I immediately understood from what was happening and how it was described that this game is not just about play. In the second anecdote of this story, these individuals weigh themselves “against the heft of morning as it dragged itself above the hills.” We are immediately thrust into the world and logic of the narrator, underscored by self-destruction and disordered eating. Each word feels so deliberate as you construct and connect the internal and external elements of the environments of the story. Since you find such accurate actions and use subtext so effectively, what’s your process in developing and/or collecting these details, and how do you ensure they all fit together?

SL: One idea that I always come back to is this concept of having an “ecosystem of language.” I did not come up with this term, but an ecosystem of language is where all the language throughout the story has a consistency in it regarding tone, image — kind of like how an image system might work. When I pick the metaphors that I use, I draw upon this ecosystem of language or image system to make this language like a figurative minefield, or figuratively like choking. Choosing to describe them in this way provides a lot of additional subtext that further frames what is literally going on in the scene.

A similar idea that I come back to when writing figurative language is what Ocean Vuong has said about metaphors and about sensory connectors and logical connectors. It is not enough that the tenor of your metaphor is physically similar or similar in a way that you can notice in your senses to the vehicle of the metaphor. There also has to be a logical connector to the specific qualities of the vehicle that become imposed upon the tenor and that adds nuance. I’m asking the implications of and the impact of describing the crab grass as choking their feet, versus caressing their feet. Caressing their feet is a terrible, terrible phrase, but just asking what is impacted by choosing that phrase over the other, what added nuance does that add, and how does that help shape atmosphere and subtext, and so on.

FWR: I love the term “ecosystems of language”, especially in reference to this collection — your strong, cohesive language really does feel like entering an immersive environment. It also reminds me of this recurring image of the knife throughout the chapbook and how poignant that image is, given the sharpness of your language. Bringing up “Changeling” again, both the chopped fragments in your writing and the cuts between sections made each part bite sized and satisfying on its own, yet each section added a new dimension to the narrative. As we move through time and discover more about Jennifer, Jessica, and their mother, and what they are living/have lived through, certain elements linger longer than others, both in terms of literal variance of length, as well as metaphorical resonance. When you were working on this piece, and on other pieces where you use this narrative structure, how did you establish this? Did you intend this choppier style to coincide with themes of familial hurt and relationships and hunger, or is this just a style that you gravitate towards?

SL: I think this style definitely lends itself to these themes of strained familial relationships and this sharp feeling throughout the chapbook. I am a big fan of the form of a work fitting the function of it.

When I am writing a story, I’m very interested in the negative space both surrounding the story and punctuating the story’s scenes: what is not being said in between these scenes and around these scenes, and how what is not being said or that “negative space” shapes our understanding of the “positive space,” or what is being said in the story. I try to be very intentional in picking certain scenes to show and make sure that these scenes have an exigence and a clear purpose. I often ask myself, “Why am I showing this scene? Why am I showing it right now? How does this develop the characters or move the plot forward?” I try to render the most focal moments or most impactful moments on the page. This often leaves a lot to be inferred in the negative space or in what is not being said, especially in stories like “Graftings,” where I have to cover a long chronology in a relatively short space.

FWR: I was really impressed by how much, chronologically speaking, you were able to fit into “Graftings” and how you were using this double lens of an unreliable narrator with Elaine and Charity, as described in CRAFT. I felt like I was alongside Charity as she was trying to understand her life, both from her perspective and from Elaine’s stories, and account for things in her life.

SL: Regarding the previous question, I also think it’s just really cool how you can have so much happen in the subtext, even in the scenes that jump between years. There’s so much that happens in between those two scenes that the reader can infer, based on where the characters are from one scene to the next, such as how things have changed or stayed the same. In that way, the reading almost becomes a collaborative process between the writer and the reader where the reader also has to do that work to uncover subtext and infer context and so on and so forth.

FWR: I think that collaboration particularly shines in “Meals for the End of the World,” where you’re using this very cool list format, encouraging the reader to make connections and collaborate with the work to make these lyrical jumps. How do you approach something that is more list-like and poetic, which may require the audience to make more leaps in logic?

SL: In my head, when I was conceptualizing this chapbook, it is a chapbook of prose, with some flash fiction and microfiction. Then when I sent it out to readers, people told me, “I really like this hybrid collection where you have stories and a prose poem and a list poem,” and I was like “Oh! That’s really interesting! I didn’t think about it before, but yeah it does function like that.” So the line between prose and poetry can be blurry in that sense.

Talking about the writing process of “Meals for the End of the World” itself, when I was selecting items for this list, I wanted there to be momentum and urgency in between the lines or from one line to the next, even if it isn’t explicitly articulated, to push you through the list and continue reading. Rather than making it feel like it’s just setting a bunch of items side by side, I wanted there to be some kind of escalation. I also wanted to pick images that felt urgent in that way, which are very vivid and very visceral as one way to push that escalation. Another thing I tried to do for this specific list story/poem is I wanted each line or each item in the list to “inherit” a word from the previous item in the list and preferably use it in a different way to really underscore the idea of inheritance through form and language. I actually messed up a little bit, but that’s okay, I’m just going to embrace that mistake.

FWR: Definitely! I think ending this piece with “Now I can swallow for two” with the final list item specifically encapsulates this theme of inheritance and working through generational hurt. This last line doesn’t just receive language; it also captures the feelings and experiences from the different stories and characters,ultimately choosing to release the hunger and hurt with the end of the collection. I thought it was beautiful.

I would love to talk a little more about this hybridization. I’ve been reading some of your poetry, both published by Four Way Review and other magazines and presses, and one thing I love is how even when you are not working in specifically prose, there’s often this clear sense of character and narrative. Similarly, I love how this prose collection had such beautiful and visceral poetic language. As you mentioned, there’s this wonderful element that blurs your work to feel like poetry and prose at the same time. Do you have a way to decipher what pieces will become poems and what will become fiction? Do you have any influences or guides to help you return to see what a piece will become? Or do you just kind of let it come out as it is, and go from there?

SL: I would say it’s mostly a gut feeling determining whether or not something will be a poem, piece of flash fiction, short story or a novel. Usually I will get an idea and I will almost immediately know which form I think it should be. There have been cases where I thought a piece would be one thing and turned out to be another, but most of the time I know in the moment. I ask myself, “What is the scope of this idea? How broad are the themes that I want to explore here? How many characters are involved? How in-depth do I have to go into their relationships and into their background? Do I have to create a whole world for this story, or can I focus in on one specific moment, or a short series of moments?”

FWR: Beyond hunger, I’ve also noticed this thread of apocalypse in your work — within Inheritances of Hunger, I’m thinking about “Changeling,” as well as “Meals for the End of the World,” but also in your poem “Prospective Final Girl Sits at the Gas Station” from Honey Literary, and I was wondering if you could speak to the appeal of writing about the end of the world and/or why you continue to return to it.

SL: I’m so glad you noticed this; I am definitely very interested in the apocalypse and I have been writing more apocalypse poems lately. I actually have an apocalypse poem forthcoming in Frontier Poetry. It kind of feels like a natural extension from my previous focus on hunger in this chapbook. I think the appeal for me on writing about the apocalypse is partially because the world does kind of feel like it’s ending, but it is less that and more that I feel like trauma often feels like a personal apocalypse. Some of the things that I went through when I was younger and that still shape who I am today felt like a personal apocalypse in that my own world was kind of ending. In more recent writing, I’ve been focusing on what comes after the apocalypse and thinking about and acknowledging the grief or the hurt of the past and wondering what to do with myself moving forward. In the apocalypse poem that I have forthcoming in Frontier, I was thinking about the appeal of losing that past and starting anew, but then the speaker decides to accept their place in the apocalypse in making a turn for preservation. Even if only for themselves, it’s like saying, “It’s okay, and maybe it’s even good if no one else knows this origin story or nobody else knows this trauma (ie. like the apocalypse).” The speaker is forcing themselves to understand what made them this way, and making the active choice to accept this and move beyond this on a personal level.

FWR: Thank you for talking about that. I’m very excited to read the poem when it comes out! I’m really interested in that premise as well as trying to navigate trauma. I’m wondering, how do you negotiate writing about what you are carrying while protecting both yourself, both in terms of self-care and safety?

SL: I’m so glad you asked this question because this is a question I ask myself and for me, well in fiction writing, I can just take these themes and these ideas and impose them on the characters and now it’s a story, right? In poetry, the line becomes a little blurrier. I think a lot about the separation of the speaker from the self and how, for me, my speakers are often a facet of myself, oftentimes put into a hypothetical situation, or put into figurative situations that did not literally happen to me. They are still an aspect of myself, and asking myself how I would react to XYZ situation is part of how I craft my speakers.

In a lot of the poetry that I write that addresses these ideas that are personal to me and that I don’t want to disclose to other people who aren’t very close to me, I will abstract these ideas and discuss them in figurative ways, or in hypothetical situations. I try to be very careful in the metaphors that I pick, or in these figurations that I create, where I can still talk about these themes and these ideas and emotions without disclosing real lived events.

FWR: That’s a really well-thought out way of approaching subject matter like this. You’re almost building in defense mechanisms and safety precautions to go about this kind of work. As a young and up-and-coming writer, how do you balance writing and everything else going on in your life right now, such as with school, family, friends, jobs, etc.? Have you found any writing “rituals” or practices other than these negotiations to be helpful?

SL: That balance is definitely hard. I will be very honest in saying that I haven’t been writing nearly as much this year as I did last year, just because of family and school and jobs. I’ve been working a lot this summer. I tutor in creative writing, so I’m surrounded by writing craft all the time. When I want a break from that, that oftentimes means not writing, which is not usually what I want. One writing ritual that I am trying to adopt and is helpful when I do actually engage in it is to just write for half an hour every day. It doesn’t have to be really anything, but just forcing myself to write for that half an hour and seeing where it gets me is better than just not writing at all. It seems intuitive, but for some reason it’s just not something that I was doing for the past few months. It’s just setting that timer and writing for half an hour and seeing where that gets me.

FWR: 100%. I often find that when you haven’t been writing, this sense of guilt from not writing starts building, and I know I can find myself in loops of self-doubt. I think a big part of getting into a consistent writing practice is learning to treat yourself with a bit more compassion and forgive yourself for not having the time. The skills are all still there, and you will be able to tap into them soon, even if it’s ten or thirty minutes — you’re still moving forward, and I think that’s really important to remember.

SL: 100% exactly that.

FWR: I know that we were talking briefly before about some different project you have coming up, as well as this thread of apocalypse in your work. Can you tell us anything about those projects? Will you be returning to any of these themes from Inheritances of Hunger?

SL: The whole thing about the apocalypse is interesting because I have enough work about the apocalypse that it is a noticeable trend, so I am thinking about maybe putting that into some type of poetry chapbook or some small scale project like that. It’s not very clearly defined yet, but that is something that is on the table.

The two big projects that I am supposed to be working on are two novels. When Cicadas Sing for the Dead is a surrealist family saga across two generations. It’s about ghosts that are both metaphorical and literal, the American dream, the past recurring into the present, and how these ideas kind of unravel in this family and in the surrealist or fabulous things that happen to them. I see a lot of times that people will say that a writer’s first novel is always kind of autobiographical, which I think is probably true for me. Even though I am not living the exact life that I am describing in this novel, it does partially take place in Pennsylvania, which is the state that I’ve been living in for the past 18 years. The character’s family is from the same region of China as my family. Beyond those superficial similarities, it addresses a lot of themes and ideas that I have been ruminating on for the past few years, including in [Inheritances], so this novel almost feels like a natural extension of this chapbook.

After that, the second novel that I’m working on is less directly tied to my personal life. It’s a lot less fleshed out, but there’s a dead girl in a pool and there’s a lot of summertime imagery. I really want to make this novel experimental form-wise and I wanted to introduce things like fake newspaper clippings or diagrams and things like that. I’ve been thinking a lot about playing around with aspects of form and oral tradition and stories within stories. One of the major thematic focuses is on archive and the fragility of paper and cultural memory, and also how real people can become mythologized through a very specific process of remembering. Then, in turn, the people surrounding this myth can interact with it and reject their place in it or try to enter it from the periphery, and then cover more about it. That’s a lot of abstractions, but those are kind of the ideas that I’m thinking about for this project. I’m really excited to work more on it.

FWR: I’m really excited for both of these projects! I’m definitely going to be checking them out once they’re in their final form.

As we wrap up, what do you want your reader to take away from Inheritances of Hunger? Is there one major overarching question or idea that is crucial to leave with?

SL: I always have so much trouble answering this question because I’m not sure if there’s any singular thing. The thing I think that makes me the most satisfied and most like I’ve done a good job is in the response to the chapbook — when somebody messages me and says, “I had familial issues and I dealt with XYZ and I really connected to this chapbook,” those people are my ideal audience, right? The fact that my themes and ideas came through so clearly to them means that I have done what I needed to do and done what I intended to do with this chapbook, and connected with who I really wanted to connect with.

Stella Lei was interviewed by Emily Judkins for Four Way Review. Emily Judkins is a queer writer and artist studying English and Film and Media Studies at Smith College. Their writing has received the Ruth Forbes Eliot Prize and has appeared in Emulate, Voices and Visions, and the Worcester Art Museum. You can reach them on Instagram @ee.jay_

INTERVIEW WITH Robyn Creswell

Forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux this fall is the long-awaited collection of poetry by Iman Mersal, translated by Robyn Creswell, titled The Threshold. The author of five books of poems, Mersal is a highly acclaimed Egyptian poet and writer, currently based in Canada, where she teaches Arabic language and literature at the University of Alberta. Her collaboration with Robyn Creswell began when he became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, with an enthusiasm for publishing more Arab poets. In addition to The Paris Review, Creswell’s translations of Mersal’s poems have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Arkansas International, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. To accompany three featured poems by Iman Mersal this September, Four Way Review poetry editor Sara Elkamel spoke with translator Robyn Creswell about The Threshold.

SARA ELKAMEL: Congratulations on your forthcoming collection of Iman Mersal’s poetry in translation, The Threshold (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)! It gathers poems from four of Iman’s collections: A dark alley suitable for dance lessons (1995), Walking as long as possible (1997), Alternative geography (2006), and Until I give up the idea of home (2013). Can you tell us a little bit about the process you went through, together with Iman, to get this collection together? How did you go about selecting the poems?

ROBYN CRESWELL: Iman is a poet of sensibility: she has an immediate, idiosyncratic presence on the page. Her voice—really a congeries of voices—is unforgettable once it gets in your ear. But it’s also a sensibility that develops in large part by looking back on prior performances: reading Iman’s work in chronological order, you have this feeling of astonishing self-sufficiency—her voice expands, matures, and addresses itself to different topics, but the transformations result from self-reflection.

When we chose the poems of The Threshold—and we discussed the table of contents endlessly, because it was fun to arrange and rearrange the poems—I think we wanted to make sure the distinctiveness of Iman’s voice came through, but also its dramatic evolution. So the poems are arranged roughly in the order they were first published, although we also made sure that short and long poems alternate, and the variety of voices is on full display.

SE: You’ve been working with Iman for several years now (I remember reading your gorgeous translation of “The Idea of Houses” in The Nation in 2015). Can you tell us how you first started translating her poetry, and how your evolving collaboration has in turn manifested in the translations?

RC: When I became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, one of my aims was to publish a larger chorus of Arab poets in the magazine. At the time, I think the only poet writing in Arabic who had been published in the Review was Mahmoud Darwish. An Egyptian friend of mine, Waiel Ashry, suggested that I read Iman. At the time, I had what I now recognize as a schoolboyish appreciation of modern Arabic poetry: I mostly read the classics (Darwish, Adonis, Nizar Qabbani, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab), and was suitably awed. Reading Iman was like encountering a contemporary: here was someone who was, I felt, writing the present (to borrow a phrase of Elias Khoury).

I wrote to Iman asking if she might be willing to share some current work with me and among the poems she sent was “A Celebration.” I love that poem—the way it begins with a figure of speech, then literalizes it (“The thread of the story fell to the ground, so I went down on my hands and knees to hunt for it”). Then the juxtaposed scenes of an encounter on a train with an Afghan woman and a patriotic rally in Cairo. The relation between the two episodes, one intimate, the other collective, is never spelled out—it has something to do with the experience of speaking words in a “foreign” language—but the idea of putting them together is what makes the poem characteristic of Iman.

After that first poem we began working on others, until the idea of a book became more or less inescapable. Working with Iman—we’ve worked very closely—has been a pleasure and a privilege. She has a knack for seeing where my English versions aren’t quite right (I’m abashed now to look at some of my first drafts), but she never imposed her own solutions. I’ve learned more from her about Arabic poetry—how it works, its range of tones, its levels of diction—than any other teacher. I’ve been very lucky.

SE: You’ve previously referred to Iman Mersal’s voice as having a “sinuous, rough-edged music” that can be challenging to translate. I also find that irony and wry humor permeate Iman’s poems, which I imagine would be difficult to always carry across into English. Do you remember any particular challenges with translating any of the three poems featured in FWR?

RC: English can do wryness, but Arabic verse has musical possibilities that I don’t think contemporary poetry in English can really capture. Because written Arabic is a literary language—it isn’t spoken except in formal situations—it’s possible to be grandly symphonic or virtuosically lyrical in a way that’s hard to imagine in English. You’d have to be a Tennyson to match the musical effects in Darwish’s late poetry, for example. But of course trying to be Tennysonian would be fatal.

With Iman the difficulty for an English translator is different, and I would say more manageable. In a poem about her father, she wonders whether he might have disliked her “unmusical poems.” I don’t think they’re actually unmusical (I don’t think Iman does either), but their rhythms and cadences and sounds have a lot in common with the spoken language. She writes in fusha, sometimes called “standard” Arabic, but her style shares many features of the vernacular: she doesn’t use ten-dollar words, her syntax is typically straightforward, economy is a virtue. She also uses tonal effects—sarcasm, for example—that we tend to associate with speech.

We talked a lot about “A grave I’m about to dig.” I’m still not sure Iman likes my choice of “diagonal” for the Arabic ma’ilan, to describe the way a bird falling out of the sky might appear to an observer on the ground (but that’s how I think of Iman: she sees things at a slant). The last phrase of the poem, “were it not for the sneakers on my feet” is a typical moment of self-deprecation, a comedy of casualness. There are no feet in the Arabic original, however, which just says “were it not for my sneakers” (or, more literally, “my sports shoes”). I thought adding the phrase “on my feet” was needed, both for musical reasons and because it suggests a pun that isn’t available in Arabic, where verse meters aren’t called feet. For me, Iman’s (musical, metrical) feet really do wear sneakers: they’re quick and agile, casual but spiffy. They’re what we wear today.

SE: Iman’s poems typically take on different forms as well as registers–at times indulging in the lyric, and at times sacrificing it for the sake of a more restrained, almost academic language. She recently told me that she believes poems don’t have “forms” as much as “personalities.” Do you find you have to “get to know” a poem of hers before you approach a translation? If so, what does that process look like?

RC: I think translation is the process—or a process—of getting to know a poem. My first versions tend to be awkward, formal, overly reliant on obvious equivalents (something like the French faux amis). That isn’t so different from the way one talks with a new acquaintance: conventions can be useful. It’s only later, and gradually, that you begin to see what makes the poem—if it’s a good poem—worth spending time with.

SE: Finally, can you tell us a little bit about the choice of title for your forthcoming collection, The Threshold?

RC: “The threshold,” in Arabic al-‘ataba, is an important motif in several of Iman’s poems. It names a site of risk, guilt, transformation. It’s also the title of a long poem that comes at the midpoint of the collection. To my mind, this is Iman’s farewell to the era of her youth. It’s a valedictory poem about Cairo in the nineties, full of Europeanizing elites, posturing poets, and entitled State intellectuals. It’s a poem of the open road that also tells the story of a generation: Iman and her friends wend their way from the Opera House in Zamalek, Cairo’s poshest neighborhood, to the ministry buildings and bars of downtown, through the streets of Old Cairo, and out into the City of the Dead—a burial ground that’s also a point of departure.

–

Robyn Creswell teaches Comparative Literature at Yale University and is a consulting editor for poetry at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is the author of City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut, and a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books.

QUEER NATURE ROUNDTABLE

In 2021, Four Way Review partnered with several other journals and presses to establish the Bootleg Reading Series. It was a partnership we hoped would continue to grow beyond the reading series and lift up the projects of each partner. We’re excited to share this conversation with some of the poets of the new Queer Nature anthology, published by Bootleg partner Autumn House Press, in conversation with one another and the ideas of “queer nature”.

“Queer Nature is a groundbreaking anthology of more than 200 LGBTQIA+ poets writing about nature. Left out of the canon but with much to say, these writers peculiarize bodies into landscapes, lament the world we are destroying, and sing of darkness and love, especially along the beach. If nature is a monocrop, no single aesthetic, attitude or voice defines these poems from three centuries of American poetry.”

Michael Walsh, editor of Queer Nature, is a 2022 Lambda Gay Poetry Finalist. He received his BA in English from Knox College and his MFA in Creative and Professional Writing from the University of Minnesota—Twin Cities.

FWR: Which queer poets have inspired you? Which queer poems? If any are pastoral, do you notice anything new about them in the context of queer nature?

“You know, I have a lot of embarrassment about being pretty under informed about poetic movements or styles. I studied English and creative writing, but thought more about individual poems. This is just to say I’m not certain I understand what the pastoral is, but I do love a lot of poems that figure and transfigure the natural world. I think of poems like “Tiara” by Mark Doty, which puts drag queens next to lush water, next to death and sex.”

Eric Tran earned his MFA from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and is the author of Mouth, Sugar, and Smoke (2022), forthcoming from Diode Editions in the spring, and The Gutter Spread Guide to Prayer (2020), from Autumn House Press. He is also an Associate Editor for Orison Books and a resident physician in psychiatry at the Mountain Area Health Education Center.

“I consider poets like Elizabeth Bishop and Audre Lorde to be major influences in my development as a poet. I was introduced to both poets in college and graduate school. My first attempts to write about my own queer experience were influenced by “The Shampoo” by Bishop, in which the simple act of washing her lover’s hair inspires an image of shooting stars, suggesting to my young mind that love between two women is such a revelation that it compels images of heaven. The movement toward metaphor in this poem was indicative of the deep nature of a sexual relationship between two women. I experienced the same sense of revelation in Lorde’s “Love Poem” where intimacy pushes the speaker toward seeing her lover’s body as a forest and her own entry into it as the wind, as she opens widely to “swing out over the earth over and over again.” As an imagistic writer, I struggled to write about sex in an overt way; however, the metaphor invites great possibilities for writing about intimacy between women.

“Neither of these poems is pastoral; however, you ask an interesting question in the context of environmental poetry. Much of the nature poetry being written today is a movement away from pastoral writing. There is too much that stands in the way of the effort to ‘touch’ God through one’s experience of nature—abuses of the land, water, and air, not to mention our current focus on the power of place where the land itself has connection to indigenous peoples and histories that far more important to acknowledge, at least in my mind.”

Amber Flora Thomas earned her MFA at Washington University in St. Louis and is the author of Red Channel in the Rupture (2018) from Red Hen Press, The Rabbits Could Sing (2012) from the University of Alaska Press, and the Eye of Water (2005) from the University of Pittsburgh Press, which won the 2004 Cave Canem Poetry Prize. She is also the recipient of the Richard Peterson Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize from Rosebud magazine, and the Ann Stanford Poetry Prize.

“My poetry would not exist without the poems of [Constantine] Cavafy; his dreamy stagings of sex and history are always close to me; his frankness and the undramatic way his poems unfold have taught me so much about managing energy in short lyrics. James Merrill was the first poet I loved unreasonably. Henri Cole and Carl Phillips are two poets of my parents’ generation whose work has been indispensable to me from the beginning. They are both represented with brilliant poems in the Queer Nature anthology—both poems in some way about the way we look to the natural world to teach us about ourselves, our desires, and how the natural world always complies and refuses us at the same time.”

Richie Hofmann is the author of A Hundred Lovers (2022) from Alfred A. Knopf, and Second Empire (2015), from Alice James Books. He received his MFA at John Hopkins University and is a Jones Lecturer in poetry at Stanford University.

“The queer poets and academics whose work has been foundational in critiquing Western constructions of Nature (and thus The Human) in my work are Sylvia Wynter, Katherine McKittrick’s Demonic Grounds, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson’s Becoming Human, Gloria Anzaldua, Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem, Vievee Francis’ Forest Primeval, Jake Skeets’ Eyes Bottle-Dark and a Mounthful of Flowers, and Natalie Diaz’ Postcolonial Love Poem.

“These works reveal how the “Nature” of the Western imagination is an inherently colonial concept. “Nature” conceived as terra nullius, or empty “virgin” land, by using the very word, invents the land as an unpeopled, undisturbed habitat outside of time, removed from the urban, and evacuated of Blackness, indigeneity, and queerness. National parks—“America’s Best Idea”—are racialized spaces defined by the absence of race, and serve to dehistoricize the land from its indigenous history and frame conservation as a value rooted in rugged individualism and self-sufficiency. In the construct of “nature,” indigenous people are confined to prehistory—if nature is prehistoric, then what we do to it does not affect our future. In the Western imagination, “Nature” is separate from us, just as the body is separate from the mind, and becomes an object—a place to go, a thing to be experienced, a resource to extract from—rather than a living being surrounding us, full of beings with whom we share a destiny. The concept of “Nature” is primitive, and necessary to construct the (white, Western) Human who has evolved beyond it.”

Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, author of award-winning Beast Meridian (2017) from Noemi Press and essay collection CHUECA, forthcoming from Tiny Reparations Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, in 2023. She is a recipient of a 2021 National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship and PhD candidate at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

I think animals abound in queer poems as metaphors, false or correct, of fully living in a body.

FWR: Queer desire carries an inherent subversion of expectation, and with it, potentially, greater freedom of form and image. What are “the birds and the bees” of queer erotic poems? What metaphors are found in the biomes of queer poems, especially sexy ones?

AFT: I have been trying to find my own answer to this question. I have written about my experiences as a child of retreating to the woods as a place of safety. Often, I would find myself hiding in the woods where I could watch my family, seeing through the trees a world that could not embrace my queerness. I take my queerness to the woods where it is not moralistically judged by the trees or other flora. This question reminds me of Carl Phillips poetry and essay, especially his “Beautiful Dreamer” chapter in The Art of Daring, which describes stumbling on three men having sex against a tree in the woods. Perhaps the wilderness provides cover or separation from societal judgement, which is why we have so much to say about queerness and nature.

VAV: Nature was never accessible to me growing up—I was born on the US/Mexico border and grew up in Houston, Texas, an ever-sprawling, drowning city under construction where Nature is at least an hour drive away near the state prison, and where white flight takes its suburbs and fells trees to make room for endless strip malls and megachurches.

Still, nature asserted itself in surprising and subtle ways in the Black, Latine, and queer neighborhoods of Houston where I grew up. My childhood home is near Acres Homes—a historic Black homestead nestled between highways, famous for its barbecue and horse-mounted Black cowboys; I attended Pride at seventeen and got my first HIV test at the free clinic in Montrose, the (now fully-gentrified) historic gayborhood of Houston along Buffalo Bayou; I biked through the white-oak-lined side streets of Third Ward, Houston’s historic Black neighborhood, to attend the University of Houston. And as a child, the swampy young pines behind our house haunted my imagination and stayed with me long enough to inspire the inner nightlands of Beast Meridian.

Those pines were where I escaped the confines of gender and jumped my bike over ditches with boys, smoked cigarettes and listened to music with the bad kids, escaped angry parents to read The Bell Jar under honeysuckle, tagged anarchy symbols under bridges, explored flooded creeks and caught crawfish when the power was out after hurricanes, kissed and touched and undressed with every gender under the stars. After I got caught sneaking out at thirteen, my parents took my bedroom door off its hinges permanently, so throughout adolescence, the pines were the only place I had any privacy, the place where I became brave, the place that held my forbidden self, a sanctuary of desire that made safe my secrets, the moonlit clearing where young love blossomed in my body, a haven for a young girl in trouble to hide. My girl, my girl, don’t lie to me, tell me where did you sleep last night / In the pines, in the pines, where the sun don’t ever shine, I would shiver the whole night through. That vision of nature informs every poem in Beast Meridian, from “Malinche” to “Girlbody Gift” to the final sequence, “The Way Back”—the nightlands of forbidden desire, rebellion, trouble, alienation—where the speaker grieves her monstrosity until she can finally embrace her animal, and in so doing, sets herself free.

Queer nature is a catapult out of the limits of a single human body. It is a breaking out, a widening into the possibilities of a transformative understanding of boundaries of self.

RH: Being queer, I think, forces one deeply into one’s body—you become more aware than other people about the arbitrariness of gender and the randomness of having a body. I think animals abound in queer poems as metaphors, false or correct, of fully living in a body. Free from desire and emotional pain, social torment, strictures of marriage and morality. In my own poem, “Idyll,” the speaker desires to shed his skin; the act of speaking, of confessing to desire, is an act of undressing.

ET: I love this definition of queer. I think sometimes we think of queer as undoing or transforming, but often I think of queer as revealing what has always been. Rather than leaps, I think of sinking deeper into, of falling, of lying and pressing (as fingers into the soil)–all of which are unsurprisingly very sexy actions to take.

FWR: What does queer nature mean to you? If you experienced the HIV/AIDS pandemic, has experiencing the Covid-19 pandemic caused you to consider “nature” more than in the past?

RH: This is a hard question for me. I feel somewhat ambivalent about both “queerness” and “nature.” I don’t think of myself as a pastoral poet. I’d rather be in a museum than in a forest. But reading Queer Nature, I feel such a profound kinship with writers I’ve never met.

AFT: Queer nature is a catapult out of the limits of a single human body. It is a breaking out, a widening into the possibilities of a transformative understanding of boundaries of self.

I don’t have much to say about the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the Covid pandemic. It angers me that most people still think of HIV/AIDS as a ‘gay’ disease. Most people do not see the parallels. Most people can’t get to the point where they see how greed, environmental degradation, and ignorance lead to pandemics.

the act of creation is forever fused with subversion in nature

VAV: The nature of my youth was not the normative Nature of national parks or state reserves—it was a nameless, swampy half-acre of undeveloped land behind our house, where flooded ditches gouged the boundary between our neighborhood and the trailer park next door. That nature was where the “bad kids”—the troubled kids, rebels, outcasts, queer kids—found each other, not recognizing that our bond was not in our badness, but in shared trauma and alienation. The only way to get to our nature, queer nature, was to be disobedient, daring enough to break a rule, stay out after hours, trespass, know where to jump the fence. The forbidden places I went to skip school, smoke cigarettes, skinny dip, drop acid, give and get head, kiss both girls and boys, fuck in cars until police pulled up, were also where I went to read, write, and play guitar. And this has had a fundamental influence on my artistic practice—the act of creation is forever fused with subversion in nature. Nature and art are sites of disobedience, rebellion, and provocation—if I am not being subversive, vulnerable, provocative, brave, then I am not making the art I want to make.

Now in single motherhood, I live near Griffith Park and Southern California beaches, and nature is a haven from isolation and endless responsibility, an expansive companion that quiets my troubled heart, holds my grief in rosy light, and sends me guardians to guide my path—still deer, scrappy coyotes, vigilant owls, hovering hummingbirds, tumbling dolphins, fragrant artemisia—their presence urging me to go on when the world feels impossible and love never comes. Now, nature is where I go to slow down time and listen to the open, be with when there is no one, be with until there is.

ET: I think queer nature asks about access and owning and belonging. I think in both of these epidemics, we had to reckon with the truth that very little is owed to us and in fact, we are obligated to return our bodies to the natural world eventually. That sounds very bleak but what I mean is that my idea of queer nature is to be freed of invented obligation and restriction and to discover and experience what is opened.

INTERVIEW WITH Raegen Pietrucha

FWR: To start, I was hoping you might speak about the pull of Greek mythology, both in its use as a framing device for some of the poems and a source of imagery in others.

RP: When I drafted my first poem about Medusa way back in 2007, it was about a different subject entirely. My mother had survived breast cancer and been in remission ever since her double mastectomy, but I’d come to realize that something significant had changed in both the way some men perceived and treated her (and women like her), as well as the way she perceived herself. Something about that recalled to my mind the mythic woman with snakes for hair, that body transformed into something so terrifying that it also physically petrified anyone who looked upon it.

But as I delved deeper into the myth — or the myriad variations of the myth — I moved away from that idea and toward what, to me, is the real crux of Medusa’s story: She is a woman who, in many versions of the myth, is raped by Poseidon on the altar of Athena; then, as if that wasn’t heinous enough, she is transformed into a monster. And this is the story of so many women (and others, not just women) to this day. That realization was too powerful and potent to ignore.

And there were a lot of directions I could’ve gone in telling any story of survivorship. I suppose I could’ve just stuck to a contemporary story or set of stories; I could’ve also written it in prose, but poetry specifically allowed me to bridge important gaps between fiction and nonfiction in a way that felt natural, seamless, and protective because poetry can be both and neither of those things — fiction and nonfiction — at the same time. But to me, there’s something very powerful about pointing back to something so old, because it effectively allows me to say, “Look! Look at how much time has passed, and look at how this still has not changed. That’s not OK.” Something as old as Greek myth allows you to do that. Another thing about the myth, specific to Medusa, is that the story of her becoming a monster in so many versions quite literally relies on that singular act of sexual violence at the hands of Poseidon. Before that, without that, she is portrayed as an average woman — beautiful, perhaps, but a physical form we’d recognize.

But because most mythology (Greek or otherwise) also comes with its own set of images — symbols — which seem to be more fantastical to us in today’s world because they are so far from our lived experience— it is a rich trove from which to draw imagery and metaphor. While you can reinterpret the meaning of that imagery, as I did often throughout the book, a lot of it was more or less handed to me as part of the original story, from the snakes to the ocean to the stone — all of which, it seemed to me, related very specifically to sexual assault survivorship. And with any luck, in Head of a Gorgon, I’ve built out those ways in which I saw the myth’s imagery and the subject of survivorship connecting.

FWR: I was intrigued by starting Head of a Gorgon with the Flash Forward section and “The Gorgon’s Parting Thoughts”, which, to me, created a structural ouroboros. How did you decide on the structure of the manuscript?

RP: I love that concept: a “structural ouroboros”! That’s an awesome way of describing it! I’m stealing that!

The reason we flash forward to an end at the beginning is twofold. One, I was taking a feminist theory course in grad school while working on my thesis, which was how the concept for Head of a Gorgon started, and one of the things we discussed is the experience of time as it relates to gendered experience and society. Some suggest women’s experience of time is more cyclical — think menstrual cycles and the like — whereas men’s might be considered more linear — and here I think we can infer what the reference would be to in that case. I wanted both, especially since, in some versions of the Medusa myth, she actually represents the circle of life (birth, death, and rebirth), but this writer exists in a patriarchy.

The other aspect relates to the title and what is actually going on overall in the book. That moment when Medusa “dies” right at the beginning is the opening up of her head, from which this entire story is able to pour. In some versions of the original myth, when Medusa is beheaded, Pegasus and Chrysaor fly out. It’s quite a stretch to consider the book itself Pegasus or Chrysaor, but the idea of something having to end, in order to begin again and/or get to the core of its meaning made sense to me in the framework of this version of the myth.

FWR: Building off the idea of the ouroboros, I thought the use of repetition was powerful, particularly in the return of the “Your Captain Speaking” poems. Upon my first read of the first instance of a poem titled this, I was struck by how the poem pointed to voice and power structures: “who cares what other stories have told you? /… Who retains the right to name?”. Repetition returns later, with both secrets kept and new relationships reminiscent of old. Could you talk about what drew you to repetition?

RP: There is so much related to survivorship that reinforces, that ruminates, that obsesses. It can be very cyclical in quite literal ways: Being sexually assaulted at a young age, for instance, puts victims at a higher risk for being victimized again in the future. The physical experience could have ended, but the survivor’s mind can replay it over and over (i.e., PTSD). It can, in many ways, become all-consuming. So repetition is essential, to me, in portraying some fundamental aspects of the experience of survivorship.

Specifically with respect to the three “Your Captain Speaking” poems, originally, those three poems had different titles when they were first published. But at some point, as the collection really started solidifying, it seemed to me that those three poems in particular, which were always similar in tone, were more or less coming from the same sort of persona, and it was someone I didn’t want to specifically name because I wanted to leave that open to the reader’s interpretation. But how could I still signal to the reader that these three poems are from the same persona just like poems from the perspective of “P” are all Poseidon and the capital-“S” Snake is also a singular persona?

I happen to be a huge Louise Glück fan — her poem “Mock Orange” was transformational for me as a writer — and she actually has three poems interspersed throughout her collection The Seven Ages that are all titled “Fable.” So I thought, “Well, maybe that device can work here, too.” In that sense, the title of those three poems in Head of a Gorgon is a bit of an homage as well.

FWR: Another form of repetition were the “Shedding Skin” poems, which are erasures of poems that appear earlier in the manuscript. Can you talk about the development of these poems?

RP: If repetition is symbolic of what traps a survivor, then strikethroughs/erasures/rewriting can be considered symbolic of freeing oneself of that cycle, or at the very least creating something new. But there was something early on for me with this collection that called to me to recognize that the change and escape needed to be physically represented on the page, and erasure — making something new and empowering from something that had once been used against the self — was a physical, visual, tangible way of accomplishing that.

FWR: One of the poems that first jumped out at me was “Sex Ed,” which I thought both played with the reveal of information, on a multitude of levels, and struck me as an exploration of innocence and loss, particularly the lines “naming things commands / nothing”.

I’ve been thinking about the Teju Cole essay “Death in a Browser Tab” recently and how artists can make sense of violence (in its many facets) without emphasizing the act, but rather the human experience of it. How did you balance the tension between naming the act of violence (and violation) and centering the person experiencing it?

RP: Did I balance the tension? I’m not sure I know, because that wasn’t something I specifically set out to do. And I think that’s because it’s my belief that there’s no amount of telling someone what a certain experience feels like that will make them actually experience the thing. Words themselves are symbols — like how maybe one way we can think of Rene Magritte’s “The treachery of images (This is not a pipe)” is that he is directly acknowledging that an image of a pipe is not the same as having an actual, 3D pipe in one’s hand.

So even in the Cole essay you referenced, for example, the viewing of another’s death doesn’t give the viewer the experience of personally dying, nor does it provide them with the experience of someone killing, nor does it even provide the experience of witnessing such events firsthand; it provides only the experience — still undoubtedly traumatic, still undoubtedly tragic — of witnessing those types of things at a distance, on a screen. But the viewer is feeling a set of feelings that may or may not be similar to any of the other three real-life experiences not actually experienced by the viewer.

I very much hesitate to say that artists “make sense” of violence or any other thing, for that matter — at least to anyone besides the artist themself. But having the belief that no amount of explaining or describing any act is going to make someone who hasn’t personally lived through it experience it firsthand or understand that experience as someone who has lived through it — and even two people experiencing, say, the same violent act will experience it differently, though there’s more common ground between the two — leaves a writer with the option instead to create some other type of experience that the writer (if the writer is like me) hopes draws toward something maybe approaching a universal truth, if there can even be such a thing, out of a real or imagined experience.

With respect to a poem like “Sex Ed” specifically, I simply set out to give voice to a woman, Medusa, who is sidelined and silenced in most tellings of her own story. And there are certainly other interpretations of this voice and story based on who’s doing the telling. We need common terms to refer to in this case — sexual abuse, assault, rape — so that people have some sense of general foundation of what’s being discussed. But from there, words are just a different experience than those actual physical, real-life experiences entirely. This is where words — and for me, any art form — will always fail. Still, I do believe in the power of words — some power in them — because look at the harm they can also cause. It’s not a physical violence, per se, but it is a violence nevertheless.

Is this all confusing, contradictory, paradoxical? I suppose. But it’s still all also true, at least to me.

FWR: I was also drawn to the poem “Cheer”, which spoke to ideas of power and heroism, as the speaker details “hoping the right / words paired with the right actions will someday / help me take some form of flight.” I read “Note From the Nadir” as a response to this childhood optimism, as the speaker wrestles with the fact that “no savior awaits”; now “I know the hero I sought will never reach me, doesn’t exist.” Instead, “my head still ingested what was fed. / What can you do when part of the problem is you?” Assuming I’m not off base (and I very well may be), can you speak to how you developed the conversations between the poems, and overall emotional arc of the book? Thinking of heroism and the head of the gorgon, how does the story of Medusa and Perseus fit?

RP: When you work on something for a decade-plus, you probably have too much time to think about it, but I tried in many ways to build as much meaning as I could — as many layers as possible — into this work. There are a lot of Easter eggs. What you’re referring to here — the conversations among the various poems — was very much considered and deliberate. This is easier to do when you have a narrative arc and are kind of building a shorter version of a novel in verse — perhaps a novella in verse. This is where my original background in fiction came into play. So I took the pieces I had, which were from Medusa’s adulthood and I thought of the parts, then, that were necessarily missing, like a childhood. And I started building some threads, images, terms that would be common among them and would evolve through the book.

Just like any person, there is change along the way; there is devolution, evolution, or both. The arc for my Medusa is devolution, to a kind of death, to a necessary evolution in order to survive — a mirroring of the birth/death/rebirth cycle that Medusa represents in some versions of the myth but that’s really all tied to the feminine in general (e.g., Mother Nature). Some of these concepts were drawn from the myth; others were drawn from survivorship. But all really echo the idea that each of us needs to become our own hero; Medusa, for me, is no exception to this rule. I tend to believe that it’s when we look outward for saviors that we are in the most danger. And I say this as a spiritual person, but one who acknowledges the truth of my personal experiences and understands that the universe requires action on one’s own behalf — like “The Drowning Man” story — in order to find one’s personal, true salvation.

FWR: What are other poems, or who are the poets, that you turned to as guide posts in the creation and construction of your poems?

RP: This book would not exist at all without Larissa Szporluk, who even beyond being my mentor and advisor is the brightest light I know in the poetry world with respect to understanding to the core that literally every story anyone ever tells is myth — and delivers that message to us constantly through her work and her teaching. Louise Glück, whom I mentioned earlier, is my top influence as far as voice is concerned; the authority of voice in her work was definitely something I strived toward in Head of a Gorgon. Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red would be a close second with respect to this collection in particular, from the mythic aspects to the narrative arc to the play with form.

Jason Shinder’s work also influenced my collection. His work feels at times as if it were written in a vacuum; he seemed to know what he needed to express was important and created a world unto itself in which the way he spoke was the only way that would’ve made sense and was therefore the best way. I wanted to create this Medusa’s world in a vacuum. I wanted the bulk of Head of a Gorgon to feel isolating, inescapable, suffocating, because this is what I imagine Medusa’s experiences in the first few sections of the book feel like.

Others of note include Marie Howe; she does an impeccable job of what you were pointing to in your fifth question with respect to speaking on the experience of survivorship. She just calls a thing a thing with such directness and clarity, yet also such beauty. Sharon Olds’ writing on all things feminine and domestic helped me to ground my work in the everyday, ordinary things of contemporary life as I transported this ancient myth into modern times. The political in Adrienne Rich’s work, of course, is essential. Monique Wittig’s Les Guerilleres, whose nonlinearity is inspiring. Virginia Woolf’s Orlando and Joanna Russ’ The Female Man for their explorations of gender. Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton for their sharp words. And William Shakespeare for his deep dive into form but also making form feel more conversational, less form-y by the standards of his time — another thing I strived toward in my collection.

–

Raegen Pietrucha writes, edits, and consults creatively and professionally. Head of a Gorgon is her debut poetry collection. Her poetry chapbook, An Animal I Can’t Name, won the 2015 Two of Cups Press competition, and she has a memoir in progress. She received her MFA from Bowling Green State University, where she was an assistant editor for Mid-American Review. Her work has been published in Cimarron Review, Puerto del Sol, and other journals. Connect with her at raegenmp.wordpress.com and on Twitter @freeradicalrp.

INTERVIEW WITH Matthew Olzmann

Matthew Olzmann’s latest collection, Constellation Route, is out now from Alice James. He has published two previous collections, Contradictions in the Design and Mezzanines, and he has received fellowships from Kundiman, the Kresge Arts Foundation and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.

FWR: Can you speak on the genesis and organization of Constellation Route?

MO: I’ve written poems that mimic a letter, or utilize an epistolary or apostrophe approach often before, and at some point I just thought that if I have fun doing that, what would happen if I did that non stop for a while? So that was the genesis; it didn’t necessarily start out as ‘I’m writing a book of these’ but instead wanting to see what direction the writing would go if I kept doing it over and over. How long would it stay interesting for me, this thing that is often a default mode for me? Would it remain interesting or would it evolve? Would I make new discoveries? I think sometimes in writing, there’s the impulse to reinvent the wheel each time you sit down and write, but if something seems interesting to you or something feels productive, you should try to do that again.

I thought [the organization of the book] would be easier than my previous two books because in those books, the subject matter is somewhat disparate, so that challenge was to see how I could get these things to fit together. With [Constellation Route], since they all have a similar approach or they’re about postal terminology, it felt as though there’s already a governing logic for why they belong in the same book.

But then I started having new challenges. For example, when so many poems have the same approach, how do you create variation, how do you change things up? That affected the writing process later, as I tried to write things in new directions. Then [this book] had all the challenges my other books have had. Even though there’s a formal approach that makes [these poems] similar, the subject matter and tone can vary widely. It ended up having all the old challenges and some new ones, just to make it interesting.

FWR: As I was reading through it, I loved the moment where poems came back to a subject or referenced a previous poem (for example, “Letter to the Oldest Living Longleaf Pine in North America” and “Letter to the Person Who Carved His Initials into the Oldest Living Longleaf Pine in North America”). The opening and closing poems to me seemed really set, so I had wondered if you had written “Day Zero” and “Conversion” with the intention of having them as those bookends.

MO: I didn’t write any of those intending for them to be in a specific position; “Day Zero” had a different place in the book, and Jessica Jacobs said I should start with that poem. As I was putting the book together, some of those things were things I was aware of. I wanted to spread them out so there was this echo.

FWR: To build on that idea, I’m struck by how writing the same structure of a poem, an epistolary or an apostrophe, is reminiscent of how an echo can lead to deviation. There’s the sameness, but also beauty in the deviation. It reminds me of how a postal route works– presumably, you’re going through the same route and making the same stops, but you’re seeing them in new lights or in new ways as you move through the seasons or through a place.

MO: The post office, despite my limited knowledge of some aspects of it, ended up having some influence on not only the poems but also the shape of the book and the language. Looking at the glossary of postal terms, wing case, day zero, everything seemed to be like an institution made by a poet.

FWR: In a conversation with Kaveh Akbar, hosted by A Mighty Blaze, you spoke about play in poetry as a spiritual or meditative practice, and how “irreverence requires acknowledgement of something grand”. To what extent do you feel you’re using humor as a bridge to the reader, or even to deflect someone’s guard being up?

MO: I think in our daily lives, we can use humor to attack or criticize, but also to charm and entertain, or to diffuse tension. We can use it to introduce an idea or to present something in an unexpected manner. I think in poems or stories, or perhaps any kind of writing, one of the things that’s useful about humor is that it disrupts the reader’s ability to anticipate to a degree. As a writer, I’m generally interested in humor because it creates a point of contrast. I like poems that have more than one emotion, especially placed next to each other. Sometimes it’s because an emotion next to the other sets off the second, whether that’s moving from certainty to doubt, or anger to something more meditative, from grief to wonder. I’m also just drawn to writing as a reader and as a writer that isn’t presenting human experience in a monotonous way. I feel both terror and wonder when looking out into the world, and I’m trying to find a space where both of those can exist in the writing process.

FWR: The poem “Letter to Matthew Olzmann, Sent Telepathically from a Flock of Pigeons While Surrounding Him on a Park Bench in Detroit, Michigan” comes to mind, and how it moves from the absurd to this greater, more empathetic commentary. As a teacher, I think that humor helps open poems up and make them accessible or an experience to be shared. And that transition, from the human to a more humane tapestry to find oneself in I think works really well in this collection.

MO: I see what you mean about humor being a point of connection. When I think about other artists who I’m drawn to, there’s something about humor that feels, in the audience, engaging or charming. It can feel like I’m being let into something– when you’re both laughing, you feel like you’re in on the joke. It’s hard to imagine who’s reading a poem when you’re writing it. I have some people in mind, sometimes, I’m always going to share what I write with my partner, Vievee, but after that, when the poem goes into the world, I have no idea who’s reading it. I like the idea of it being accessible to some people who aren’t necessarily poetry scholars or writers.

FWR: In the title poem, “Constellation Route”, you write:

…a messenger… gets wildly lost. It’s night.

Lonely. He glances to the sky–

inside that disorder,

he finds one light that makes sense, and that’s enough

to guide him to the next stop.

For me, that was the moment where a lot of the poems clicked, where I felt like I could name the theme that I couldn’t quite put my finger on previously: the idea of community. This fits what we’ve talked about with how humor forms connection, but also the letter form as a way of asserting a community (of friends, of writers). This seemed to come up again and again in your poems, whether “Fourteen Letters to a 52-Hertz Whale” (“Do you ever wonder that because your voice is impossible to hear, maybe no one will make the effort? That you can work really hard and try to be a good person… but then… the waves will just swallow you whole?”) or “Letter Written While Waiting in Line at Comic Con” (“…it’s not/ these costumes that amaze me; it’s always been/ the languages. The way they reach/ for something that can’t be said/ in our tongue.”).One of the things you seem to be reaching at is how we form and maintain community, and then, looking at the United States, how might this idea of community be under threat or at risk of change in ways that might not be particularly kind.

MO: I don’t know if I was thinking of community as one of the primary thematic drivers of when I was making the book, but I started to become aware of that later. One of the reasons I might not have been aware of it in the writing is that I tend to write poems one-at-a-time, without necessarily thinking of how they relate to one another. I write the poems and assemble books later.

But when I started putting Constellation Route together, one of the things I was thinking about was how to make things feel communal. This was part of the reason for including letters with other people in them (such as “Letter to Matthew Olzmann from Ross White, Re: The Tardigrade”) to give the sense that there were more people involved than one version of Matthew.

One of the questions I was asked recently is if the speaker in these poems, excluding those obviously persona, is me. Are the poems autobiographical? While I think it would be hard for all of them to be me, I’m sure all of them contain aspects of me or some aspect of my world view. Oliver de La Paz said something about his own poems about autobiography that really resonated with me, the idea that in an autobiographical poem, the speaker resembles you the way John Malkovich resembles John Malkovich in Being John Malkovich. I might be taking this quote out of context, but I think the speaker in any of my poems is a performance of the self. It might represent the self but it’s a performance or an aspect of the self, and there can be many of those.

You mention the conversation with A Mighty Blaze and Kaveh [Akbar], and before that, he and I were talking about how the book we haven’t written, the one that’s still in your head, is always perfect, or has the potential to be. Before you’ve made it into an object, it’s this thing that exists in the realm in perfect speculation. Most of the poems, once I tried to write them, it was a pretty messy process. Messy, but some of the fun is making discoveries. A lot of the poems, I might have a line or a vague idea, but I don’t necessarily sit down with a thoroughly mapped out route toward a destination in mind.

I like writing for the process of writing. I like the process of being there and working. There’s a point when I’m working on a poem that I’m imagining it as a point of connection. I imagine how someone might read it, and then it becomes a moment where I’m reaching for a point of contact. Rather than withdrawing from the world, it feels like working on a way to venture out and make contact with people.

FWR: Thinking of connection, or perhaps the perfect poem, are there poems that you love to teach, that do what you’re reaching towards?

MO: It’s constantly changing. It’s a list I’m constantly adding to. So many poems that I love to teach and some of the old standbys: “Iskandariya” by Brigit Pegeen Kelly; “It Is Maybe Time to Admit That Michael Jordan Definitely Pushed Off” by Hanif Abdurraqib; “Wishes for Sons”, by Lucille Clifton, or “Sorrows” or “note, passed to superman”– I remember the first time I read her series of notes to Clark Kent, I remember thinking, “you can do that? You can write notes to these people?”; Rilke’s “The Archaic Torso of Apollo”; “Brokeheart: just like that”, by Patrick Rosal or “Guitar”; “Ode to the Maggot” by Yusuf Komunyaaka; Campbell McGrath’s “My Music”; Cathy Linh Che’s “Poem for Ferguson”; most of Szymborska’s poems. I like talking about her poems “True Love” and “Pi”, “Notes From a Nonexistent Himalayan Expedition”, “A Large Number”, “The End and the Beginning”– I could go on and on.

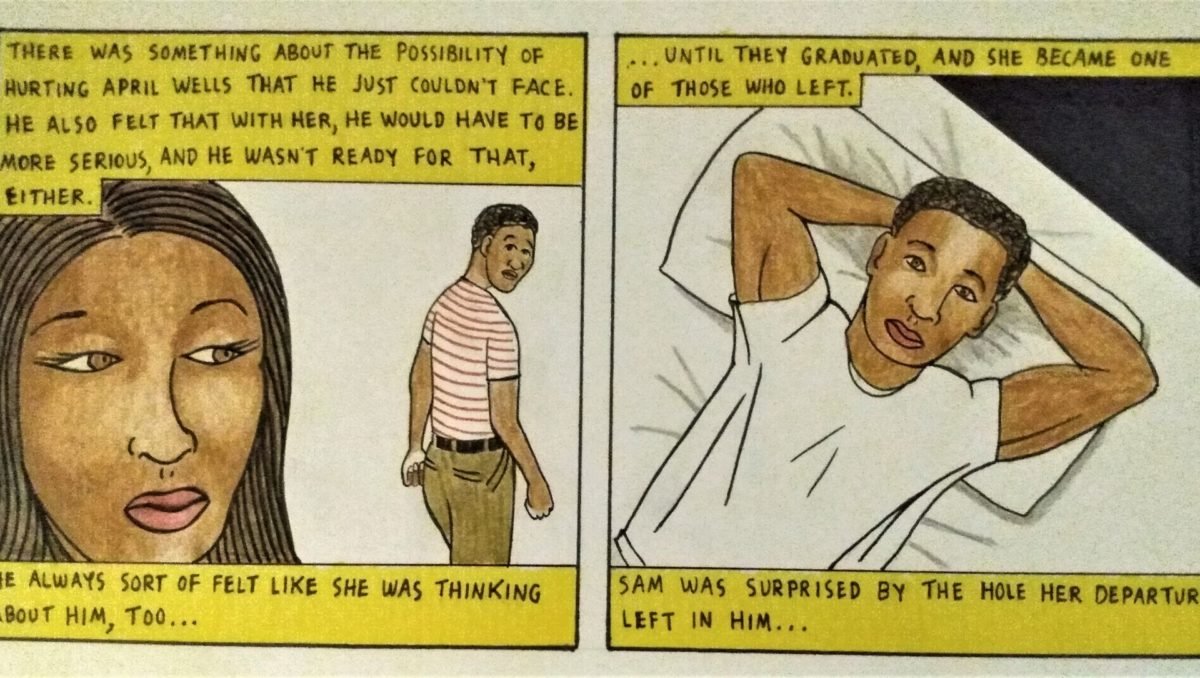

INTERVIEW WITH Clifford Thompson

Clifford Thompson is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award for nonfiction in 2013 for Love for Sale and Other Essays, published by Autumn House Press. He has also published a memoir (Twin of Blackness), a novel (Signifying Nothing) and a nonfiction book (What It Is: Race, Family, and One Thinking Black Man’s Blues). Thompson’s graphic novel Big Man and the Little Men, which he wrote and illustrated, is due out from Other Press in Fall 2022.

FWR: Having read a lot of your fiction and nonfiction, I was excited to hear that you’re publishing a graphic novel, Big Man and the Little Men, due out next year from Other Press, which you’re writing and illustrating. What does this process look like? Do images come for you before writing, or vice versa? Many writers map out ideas through drawing. How does creating your own illustrations affect your writing process?

CT: I begin by writing. The script comes first. The images are in my head, if only hazily; I’ll write, for example, “Three-quarter view of men on right side of the table.” But I don’t put those images on paper until the real illustrating begins. The script is largely a series of IOUs to myself. That is, it’s easy to put in the script, as I did at one point, “Drawing of a baseball game.” The payment comes due, you might say, when it’s time to illustrate that panel, when I sit at my drafting table and think, “Oh. Right. Now I’ve got to draw a baseball game. How do I do that?” So as a writer I put myself in positions that I then have to draw my way out of. In that way, there’s a certain amount of improvisation involved. (I find it hard to resist allusions to jazz.) For example, when it comes time to draw those men on the right side of the table, I may decide as I’m drawing that one of the men is giving the other a sidelong glance.

FWR: The prose in a graphic novel has to be so crisp and focused on action. How do you work within these limitations? Do you overwrite, then whittle down, or do you have other methods?

CT: One challenging thing about a graphic novel is that there are practical considerations of the kind you don’t run into with a regular novel, or even with painting. One is that you can fit only so many words in a panel. So I may discover, as I’m doing the actual lettering for the dialogue I’ve written, that not all of it will fit, or at least not comfortably. Then it’s a matter of rephrasing the dialogue, retaining its flavor while making it as concise as possible. Sometimes I end up improving it, almost by accident.

Writing and painting are similar for me in that the idea is half the battle. Once I have an idea, the challenge is to find the best way to carry it out.

FWR: How does starting a written piece compare to drawing or painting? Has your graphic novel bridged these two approaches, or does it feel like a different approach entirely?

CT: Writing and painting are similar for me in that the idea is half the battle. Once I have an idea, the challenge is to find the best way to carry it out. When I’m writing, that often involves lists. I’m a big list-maker, especially when it comes to essays. I like to list aspects of the subject I want to write about, then study the items on the list to see what the connections exist among these seemingly disparate things or ideas; I’ll draw arrows from one thing to another. Sometimes I find a lot of arrows going to the same item, and that can be a sign that I’ve hit on something. For paintings, once I have an idea, I pull out my sketch pad and work out the composition, the proportions and relative positions of everything. I have the sketch-pad drawing next to me when I make pencil outlines on the canvas.