Ae Hee Lee is a Wisconsin-based poet whose debut collection, Asterism (Tupelo Press, 2024), was...

INTERVIEW with AE HEE LEE

INTERVIEW with ROBIN LAMER RAHIJA

Robin LaMer Rahija‘s first full length collection, Inside Out Egg, was released in April....

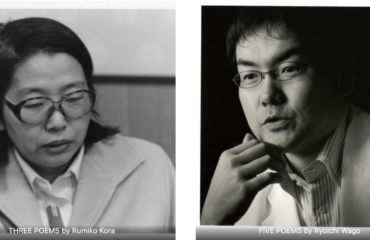

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi FIVE POEMS by Ryoichi Wa...

MONTHLY with Alexander Duringer

Alexander Duringer is from Buffalo, NY and earned his MFA in Poetry from North Carolina State U...

INTERVIEW WITH Alexander Duringer

Alexander Duringer is from Buffalo, NY and earned his MFA in Poetry from North Carolina State U...

INTERVIEW WITH Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a multimedia artist, poet, and writer. Griffiths is the author of Miracle Arrhythmia (Willow Books 2010), The Requited Distance (The Sheep Meadow Press 2011), Mule & Pear (New Issues Poetry & Prose 2011), which was selected for the 2012 Inaugural Poetry Award by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, and Lighting the Shadow (Four Way Books 2015), which was a finalist for the 2015 Balcones Poetry Prize and the 2016 Phillis Wheatley Book Award in Poetry. Her most recent book, Seeing the Body, is a hybrid of poetry and photography (W.W. Norton and Company).

FWR: I’d like to start with the titular poem, “Seeing the Body”. In it, you write into grief and how that grief can bifurcate the life of the living. In your visualization of grief, you create imagery (such as “flowers/falling from her blood” and “bale of grief on my back, opening/ into something black I wear”) that seems resistant to more common depictions of grief. (I’m thinking of poems like Auden’s “Funeral Blues” or the gothic imagery of Edgar Allen Poe, which have become synonymous with writing about loss). Did you find yourself resisting cliche, or writing through images that you had read from others, when you first began these poems?

Rachel Eliza Griffiths: The engine of “Seeing the Body” relies on how breathing happens through a poem as much as it is also about how breath stops or is altered by grief. There is the involuntary tension of trying to sustain an image or to construct a narrative about a beloved’s life or one’s self, only to find all is ruptured.

Auden’s wonderful poem is after something very different than “Seeing the Body” insomuch as Auden’s poem calls for a moment of silence that feels quite public in its address of ordinary life. My own poem wants intimacy, to address the earth and the private echo of silence where there is the sense of falling through one’s body, one’s birth and death through the body of the mother. My mother. This poem hurt me the entire time I worked on it. Years. I’ve never been attracted to clichés, visually or otherwise, so I don’t think about resisting them. What has startled and provoked me is the immediate emotional connection I feel wherever I share these poems. I’m writing about a “common” experience yet it is anything but common for me.

I can never read this poem as it should be read. That was intentional. Each time I enter the earth of this poem I am further away from its original grief. I am somewhere else in my body and can’t get back to the woman who braced herself against the initial impact of loss. Whenever anyone experiences this poem I hope there is an intimacy of reading that does not exclude our bodies. Through language, I’m aware of forcing myself to stop in the middle of something that has neither beginning nor end.

Listen to “Seeing the Body” read by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: Seeing the Body includes a section (“daughter: lyric: landscape”) composed of your photography, which is alluded to in other poems (“For years I photographed myself/ in a white dress”, from “Husband”). You write in your Author’s Note that these photos serve “as a map of the self and of the greater world in which [you] are both visualized and invisible”. Had you planned on incorporating photography from the beginning, or how did that process develop?

Griffiths: In the beginning, I didn’t plan to use any images at all in the book except I began to think about the types of photographs I had created in Mississippi just before she died. I had to go back and consider what I was “making” when I was unmade by her death. Then I also remembered the deliberate focus I gave photography immediately after her death. I clung to the machine, my camera, like a life raft. I began to perceive my own body as an urgent conduit of my grief, which meant I couldn’t leave my body outside of any landscape on the page.

Perhaps the only way now that I can truly see my mother’s body again is through studying my own. This time was weird and messy because I couldn’t read books. I had a hard time using my camera. All these tools were nothing to me. When I began to write about my mother, it was very difficult because it felt like language was forcing me to accept elements of her death I couldn’t bear.

Perhaps the only way now that I can truly see my mother’s body again is through studying my own.

FWR: Did this impact your understanding of or play with syntax? (I’m thinking here of the poems “As” and “Good Questions”).

Griffiths: “As” and “Good Questions” are fragmentary or function as what I might call a “collage of the lyric” — the rhythm and imagery bleed together in an attempt to both isolate language and to hold the visible language intact as grief itself opens through the body of the page. Photographs offered me a way to be grounded in the world, to remember there had been a world I loved before her death and that I could and must return to it. Finally, it was transformative, after so many years of being diligent that these mediums lived in separation, to ask them to touch each other and hold me.

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: “Color Theory and Praxis (I)” is a poem concerned with the body, but also the body in art. Specifically, it considers the painting “Open Casket” by Dana Schutz, which depicts Emmett Till. The poem questions who has the right to the body, particularly a body of color, and after death. I wonder if this influenced your own writing, as some of your poems see you imagining the voice of your mother, as in “Comedy”: ‘Yeah don’t go and write about me like that/ she says. I already know you will.’

Griffiths: I’m ambivalent about my relationship to placing myself inside the voices and bodies of others. I’ve done it, whether by persona or in certain photographic series, and it can feel tense for me. Issues of permission and imagination fascinate me. I’m not interested in policing anyone but I do have the right to challenge, to question, and to critique certain things, especially when it comes to visual arts and representation. There is a lot at stake for me even when it feels like people want artists to shut up when their work is confrontational. I read an interview where Schutz said the painting was about a conversation with Till’s mother. I disagreed with her perspective and the “terms” of this unreal, fantastical conversation, which placed the mutilated body of a black mother’s son as its focal point, as its medium. There is a photograph of Mamie Till at her son’s casket. I don’t feel like Schutz’s painting could ever listen to, or tell Mamie Till’s truth. The artist has a right to do whatever she wants but I tried to understand what and where that right was located. I mean, there’s a painting of hers that features Michael Jackson’s body on an autopsy table. Again, do what you want but do it well. Also, I noticed she didn’t use Trayvon Martin’s image, or Sean Bell’s, Tamir Rice’s, or Eric Garner’s, or Jordan Davis’, or Philando Castile’s, or Mike Brown’s, or Ahmaud Arbery’s, or…or…

I’m tired. There isn’t enough canvas, enough pigment, enough bones in this country for black artists to address the violence and harm done to our bodies, our communities, by the imaginations or institutions that can’t bear for us to live. It isn’t our job or our art’s job to do that work either. Why is America afraid that we dare to imagine ourselves as anything but dead?

My mother and I would go back and forth about my writing. Sometimes she’d ask me when I was going to write her story. Other times she worried about my imagination. None of the poems in “Seeing the Body” ever enter my mother’s body and use her voice. I never wanted to do that. The dialogue in “Comedy” was exactly what she said.

It isn’t our job or our art’s job to do that work either. Why is America afraid that we dare to imagine ourselves as anything but dead?

FWR: In “Good Questions”, you write, “when did the final arrangements begin? / At her birth. Inside of wet rock. When my birth began.” Throughout the text, I was struck by your exploration of inheritance, whether of womanhood or illness, and how grief lives in the body (as in “Signs”). Would you speak to the development of this thread?

Griffiths: I’m in a more explicit stage of my life where I want to think of myself within a greater dimension, in conversation with beings that arrived before me, and those who are already arriving after me. I think about what I can share with the living and the dead. I’m constantly aware that the earth is different in her temperament since I was born. I’ve been astonished by how quickly some of our geographies have reverted and have healed during the pandemic without the presence of human abuse.

At this point, my work lends me an expansive way to think about how I might, as an artist, establish or assert my own lineage or claim inheritance in ways that don’t necessarily include children. I’m constantly thinking about how remarkable it is to begin to really take into consideration the manners, culture, trauma, resilience, joys, and ways-of-being that I have inherited. These things I hold have come from my family but they have come from a larger consciousness. They also come from within me.

I’m in a more explicit stage of my life where I want to think of myself within a greater dimension, in conversation with beings that arrived before me, and those who are already arriving after me. I think about what I can share with the living and the dead. I’m constantly aware that the earth is different in her temperament since I was born.

FWR: Seeing the Body explores the shifting ownership of the female body and how language can free, as well as constrain. In “Ars Poetica”, you write of imagining becoming a writer or a woman like your mother, before the neighbor and his friend interrupt your daydream: “his friend braked hard,/ barking like a dog… Hey, Bitch, he said”. In “My Rapes” your mother asks, “why/ I listened to white girl shit. How could alternative music/ hear a black cry like mine?” Can language free us from the body?

Griffiths: It depends on so many things – whose language, which bodies, whose freedom, whose history, or memory. “Ars Poetica” speaks about some of the ways that violence can interrupt one’s dreams or one’s work. The poem is also asking questions about how we, especially black women, can afford our dreams and our work. How the world consistently fails to appraise our contributions even while our bodies and cultures will be taken as commodities, as resources. The second poem you mentioned is about some of the ways your own family will refuse to allow you (and by extension, your body) to live in songs (and bodies) that they believe are dangerous. I listened to a lot of Tori Amos because of what had happened to me. I listened to Fiona Apple, Ani DiFranco. I listened to them because my mother wouldn’t hear my truth. She couldn’t bear the thought of violation because she loved me so much.

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Listen to “Arch of Hysteria, Or, the Spider-Mother

Becomes A Woman” read by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: Building off of that question, you thread myth through your poems. For me, the inclusion of Athena, Arachne and Eurydice roots your experiences in grief and voicelessness within a larger historical and human story of being a woman. And the poem “Myth” speaks of “the literature/ of blood the black face gasps in air. No… / the black boy’s face merely insists/ it is a face to begin with”, which, to me, seems reminiscent of the commodification of bodies of color not only in commerce, but also in art. Can you talk a bit about the inclusion of these figures?

Griffiths: This question feels similar to the earlier question about Till. In some parts of the book, I found myself returning to stories about daughters who were powerful but seemed unable to overcome their roles in a larger “myth” or story. These stories would often place women inside of cruelty and violence – rapes, murders, or “transformations” that altered or punished their bodies, or drove them mad. The poem “Myth” is about my rage as well as my grief that murders of black men persist in a cycle that renders them faceless, whether that is through death or incarceration. And there is a spectrum of micro-massacres between those extremes. Their humanity is erased.

FWR: Were there poets or writers you turned to for guidance as you wrote through your grief? (Lucille Clifton’s “oh antic god” springs to mind). Or, are there poets or poems you love to teach or share?

Griffiths: Yes, I return often to Ai and Lucille Clifton! I’m thrilled at the forthcoming publication of a selected, How to Carry Water (BOA Editions Ltd.), edited by my dear sister, Aracelis Girmay. It will be a feast! When my mother died, Aracelis shared a poem with me by Joy Harjo, our current National Poet Laureate. It’s called “Remember” and I read it aloud often. If I were brave enough to get a tattoo it would feature lines from this poem.