INTERVIEW WITH Clifford Thompson

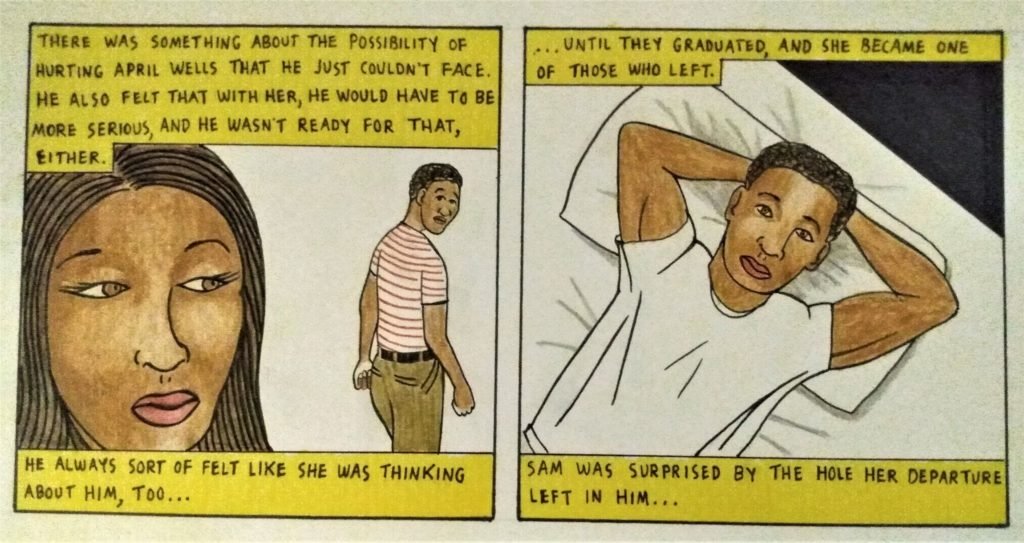

Clifford Thompson is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award for nonfiction in 2013 for Love for Sale and Other Essays, published by Autumn House Press. He has also published a memoir (Twin of Blackness), a novel (Signifying Nothing) and a nonfiction book (What It Is: Race, Family, and One Thinking Black Man’s Blues). Thompson’s graphic novel Big Man and the Little Men, which he wrote and illustrated, is due out from Other Press in Fall 2022.

FWR: Having read a lot of your fiction and nonfiction, I was excited to hear that you’re publishing a graphic novel, Big Man and the Little Men, due out next year from Other Press, which you’re writing and illustrating. What does this process look like? Do images come for you before writing, or vice versa? Many writers map out ideas through drawing. How does creating your own illustrations affect your writing process?

CT: I begin by writing. The script comes first. The images are in my head, if only hazily; I’ll write, for example, “Three-quarter view of men on right side of the table.” But I don’t put those images on paper until the real illustrating begins. The script is largely a series of IOUs to myself. That is, it’s easy to put in the script, as I did at one point, “Drawing of a baseball game.” The payment comes due, you might say, when it’s time to illustrate that panel, when I sit at my drafting table and think, “Oh. Right. Now I’ve got to draw a baseball game. How do I do that?” So as a writer I put myself in positions that I then have to draw my way out of. In that way, there’s a certain amount of improvisation involved. (I find it hard to resist allusions to jazz.) For example, when it comes time to draw those men on the right side of the table, I may decide as I’m drawing that one of the men is giving the other a sidelong glance.

FWR: The prose in a graphic novel has to be so crisp and focused on action. How do you work within these limitations? Do you overwrite, then whittle down, or do you have other methods?

CT: One challenging thing about a graphic novel is that there are practical considerations of the kind you don’t run into with a regular novel, or even with painting. One is that you can fit only so many words in a panel. So I may discover, as I’m doing the actual lettering for the dialogue I’ve written, that not all of it will fit, or at least not comfortably. Then it’s a matter of rephrasing the dialogue, retaining its flavor while making it as concise as possible. Sometimes I end up improving it, almost by accident.

Writing and painting are similar for me in that the idea is half the battle. Once I have an idea, the challenge is to find the best way to carry it out.

FWR: How does starting a written piece compare to drawing or painting? Has your graphic novel bridged these two approaches, or does it feel like a different approach entirely?

CT: Writing and painting are similar for me in that the idea is half the battle. Once I have an idea, the challenge is to find the best way to carry it out. When I’m writing, that often involves lists. I’m a big list-maker, especially when it comes to essays. I like to list aspects of the subject I want to write about, then study the items on the list to see what the connections exist among these seemingly disparate things or ideas; I’ll draw arrows from one thing to another. Sometimes I find a lot of arrows going to the same item, and that can be a sign that I’ve hit on something. For paintings, once I have an idea, I pull out my sketch pad and work out the composition, the proportions and relative positions of everything. I have the sketch-pad drawing next to me when I make pencil outlines on the canvas.

Again, the graphic novel begins for me with writing, but I would say that the graphic novel bridges writing and painting in that the written and visual aspects of the work spell each other. The graphic novel is a visual medium, but you need words. You just do. Even Kyle Baker’s terrific graphic novel Nat Turner, which is almost all pictures, uses some words. Still, some of my favorite moments of working on Big Man and the Little Men are when I can draw a panel or series of panels that speak for themselves. A motion, a facial expression, a character’s eyes looking in a certain direction, three people’s heads turning toward a fourth person who has just uttered a non-sequitur, a hug between two forty-year-olds who last saw each other in high school—panels like that can say it all. Not a single word needed. I find that satisfying.

I’ve been painting now for years, which has come in handy with the graphic novel because of all the time I’ve spent shading with colors in painting. To a certain extent I’ve transferred that process to the graphic novel: I shade with colored pencils, darkening some areas of a face, for example, while taking an eraser to other areas. That is one thing I didn’t do when I was drawing comics in high school, oh so long ago now.

A friend of mine, looking over the pages of Big Man that I’ve illustrated, observed that my unit of visual expression—he said something to that effect—is not so much the individual panel as the page. I think that’s accurate. The page comes together to form a kind of statement.

FWR: Your Four Way piece, “Quintessence,” ponders creativity—where inspiration comes from, how and why we write what we do. You’ve written a lot about music, film, and visual art over your career. Some of your artwork has a tone that resembles Augusta Savage or the stark lines of Elizabeth Catlett, another DC artist. How do other artists, writers, or their mediums inform your work?

CT: I appreciate the comparison to those women. I find that I like two things in visual art: color and simplicity. The work of the Fauves, and artists such as Catlett and Jacob Lawrence and William H. Johnson, greatly appeals to me for those reasons. In some graphic novels I read, I admire all the detail the artists put in as well as the artists’ technical ability; still, because the images are so lifelike, with so much going on, sometimes my eye doesn’t know where to go. So I try to put in a few details but focus largely on color, composition, and the central image.

When it comes to writing, I am never consciously aware of being influenced by others’ work, but sometimes people see things in your writing that you don’t see. In my book What It Is, I write about James Baldwin and Albert Murray, among others. The reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement wrote that I had blended, “consciously or not,” the “voices of [my] mentors Baldwin and Murray.”

FWR: In The Rumpus earlier this year, you explained: “It could almost be said that much of my work is an attempt to solve a puzzle.” In Big Man and the Little Men, a writer becomes enmeshed in a presidential campaign when an accusation is made against the nominee. What puzzle pieces are at work in this book, and how did you decide what form they would take?

CT: I think the puzzle at the bottom of Big Man is: how do you do the right thing when there seems to be no right thing to do? That’s the quandary that my main character, April Wells, faces. As for deciding on the form, I’m not even sure I did. The idea came to me fully formed.

FWR: I wonder if you can elaborate on this. How do you move between more planning-oriented techniques—like your lists, arrows and IOUs—to more intuitive ones? Or are you describing more of an organic gradual process of both, one feeding the other?

CT: Maybe a good analogy would be carrying out a military or spy mission (not that I have ever carried out either of those). That is to say, you can make lists and draw arrows and write IOUs, just as you get instructions for a mission; but doing the thing is where it happens—the fun and the risk, the difficulty and the discovery, the improvisation and toil and surprise.

FWR: You’ve written often about politics, including in What It Is, and most recently in a series of essays for Commonweal Magazine. Big Man too is interested in the political. Do you have any craft tips or observations in terms of how you approach political writing across forms?

CT: You know what’s funny? Until I read your question, it hadn’t occurred to me that I’ve written often about politics—maybe because the works you mention are all so different from one another. But you’re right, I guess I have. And I guess the reason is that presidential politics have fascinated me since the first election I remember, when I was nine, when McGovern ran against Nixon in 1972—still the gold standard for lopsided election results. (I’m proud to say I’m from Washington, DC, one of two places in the whole country that McGovern carried.)

I don’t know if I have any craft tips for writing about politics, but I do have one observation, which is that, fundamentally, nothing is new. That may be a good thing to keep in mind when writing about politics. So maybe that is some kind of tip, I don’t know. But here is an example of what I mean: The first five presidents of my lifetime were John F. Kennedy (who was killed when I was eight months old), Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter. Not one of those men served two full terms, and a couple of them didn’t even complete one term. So for my entire childhood, the American presidency seemed like an unstable thing. Then, for decades after that, with the single exception of George H. W. Bush, the presidents were two-termers: Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush, Obama. Then, of course, came Trump, demonstrating the cyclical nature of politics. For all the sheer, seemingly unprecedented god-awfulness of the Trump years, his shenanigans and defeat were almost like a return to my childhood. It was sort of like when people used to go into movie theaters in the middle of the movie and stay for the beginning: “I remember this—this is where I came in.” (That said, I pray that this round of chaos ended with Trump. I wish President Biden great good luck.)

FWR: Sometimes when I read your work, I’m reminded of Virginia Woolf’s concept of caves. Ideas, characters, or narratives which seem disconnected, eventually, as Woolf describes it, “connect and each comes to daylight at the present moment.” How does this process of braiding seemingly disparate elements into a single narrative work for you in making a graphic novel? Is this different than in your writing fiction or nonfiction?

CT: I am delighted by that characterization of my work, and I’ll take a comparison to Virginia Woolf any day of the week! I would say that the braiding happens more in my nonfiction, and yet, now that you mention it (you ask very good questions!), I see that there is braiding at work with Big Man. The story’s prologue has two scenarios involving different sets of characters, with no indication of what they have to do with each other. But later it becomes clear.

FWR: What’s next for you after Big Man and the Little Men?

CT: Time will tell. I have several manuscripts in various stages of readiness. One is a manuscript of poems. I said to my wife that I’m working toward publishing one of every kind of book—a joke, though not really.