shows on homepage

SEPTEMBER MONTHLY: Interview with Jessica E. Johnson

We’re excited to share a new series of interviews exploring craft. In these conversations, we’ve asked writers to take us behind the scenes of their finished works, showing us the process behind the poem, the scene, and the story.

First is our conversation with Jessica E. Johnson, on her memoir Mettlework: A Mining Daughter on Making Home. This memoir explores her unusual childhood during the 1970s and ’80s, when she grew up in mountain west mining camps and ghost towns, in places without running water or companions. These recollections are interwoven with the story of her transition to parenthood in post-recession Portland, Oregon. In Mettlework, Johnson digs through her mother’s keepsakes, the histories of places her family passed through, the language of geology and a mother manual from the early twentieth century to uncover and examine the misogyny and disconnection that characterized her childhood world– a world linked to the present.

Considering the focus of these conversations is on process, we’d be remiss to overlook our own process in conducting the interview! We’d like to give special recognition and thanks to our 2024 summer intern, Kirby Wilson, who helped shepherd these conversations from initial readings to their final form. Kirby was instrumental in crafting the conversations you now see before you.

Enjoy!

- Published in home, Interview, Nonfiction, Video

INTERVIEW with AE HEE LEE

Ae Hee Lee is a Wisconsin-based poet whose debut collection, Asterism (Tupelo Press, 2024), was selected as the winner of the Dorset Prize by John Murillo. In Lee’s poems, heritage and belonging are examined rather than embraced. Visiting her father’s old home in Chungju, Korea, she asks the flowers growing there to “remember [her] from time to time.” Asterism travels through the three countries that have shaped her – Korea, Peru, and the US – chasing the spectres of all she has been and all she could have been. Her gift for sensual imagery is tempered by a relentless questioning of beauty and nostalgia. In a poem about the bureaucracy and anxiety of re-entry as an immigrant (“Chicago :: Re-entry Ritual”), she realizes that she must erase herself with each arrival, leaving room for “love, waiting/ at every side of a border.” In this interview, Lee discusses her journey in the literary world thus far, as well as the influences and concerns that drive her work.

FWR: I really resonated with the poems about the immigration process, the anxiety of going through border control, and the numerous hoops one has to jump through in one’s journey to secure visas and permanent residency. I am curious about how the language the immigration process subjects people to may have affected your own understanding of language.

AHL: Thank you so much for reading! I would say I’m glad you resonated with these poems, but at the same time, the immigration process, the anxiety, the paperwork, the money, and the hoops, can be so stressful that I don’t wish it on anyone.

I came to the U.S. as an international student to major in Literature and lived in the country with an F1 visa for almost 10 years, as I pursued grad school as well. I ended up meeting a person I could also call home here and applied for permanent residency, but I spent a big part of my adult life continually filling out and updating form after form to maintain my stay. This made me notice how the language of the immigration process and much of the political rhetoric around it stood directly in contrast with the language of literature and the arts that I had fallen in love with and had come to study.

In a sense, these experiences clarified for me the weight of language. Yes, there is language that seeks to control, hierarchize, and/or dehumanize, but there also exist languages that can resist the normalization of the former, reclaim, rehumanize, and love. So, I thought I wanted to be the kind of poet that strives to write in a language that is centered around such love and lives it out.

FWR: Food is a recurring theme and image in this collection — it becomes a vehicle for memory, tradition, and unconventional innovation, to name a few things. I am interested in whether and how food plays a role in your creative life today.

AHL: My mother used to say she liked watching me at the dinner table, because I looked happiest when I was eating. The act of eating, savoring and sharing meals, is something I find so much bliss in that any time I encounter a dish that is delicious beyond my expectations, I have the impulse to say “I love you” to whoever cooked it or is sitting with me. I also cook at home often – experimenting and trying out new foods, indulging in my curiosity about ingredients and tastes, inquiring about their journeys, their relationships with the hands that had made the dishes before me.

The way I experience food is not too different from my process for writing poetry, as I feel out the flavor and texture of each word I encounter outside or within the context of a line, and seek to learn about and from them. Since I was a kid, I kept a notepad with Korean, Spanish, and English words that I was fond of because of how they sounded or were interesting to me conceptually. But I would say food brings me a joy that feels more instinctual and immediate, while poetry is slower, and denser.

FWR: There are a plethora of forms used in Asterism. I am always interested in hearing writers talk about their process at a granular level. Would you tell us a little about how you chose the form for the poem “NATURALIZATION :: MIGRATION”?

AHL: When I write, I tend to have my poems lead me, and form is one of the things that the poem itself will make clear for me while drafting.

“NATURALIZATION :: MIGRATION” came to me at a pottery sale organized by college students. For this poem it felt right to be faithful to the sequence of thoughts and actions of the moment: to start with being present in the location, buying nothing, then move back to past instances of movement, to finally come to a reinterpretation of the word “naturalization,” hence the title.

“Naturalization” has always struck me as a strange word. While it’s largely defined as the legal process by which a foreigner becomes a citizen of a country, it also carries the implication of assimilation and a kind of belonging that is fixed and exclusive. This all feels at odds with how every living being exists in nature, always in movement, even when seemingly in the same place (the progression of plant roots, for instance).

While admiring one of the vases, I went back and forth between the urge to possess an inert object that made me feel grounded, the yearning to subscribe to the illusion of a “permanent” home, the thought I was not a vase person, and the consideration that I love and want to embrace the wanderer and wandering in me. And so, I felt the poem move too, which is why we arrived at a form resembling a river, the undulation of squirrels.

FWR: Do you remember when you came across the word “asterism”? And would you talk about why you chose that as the title of your book?

AHL: I confess I don’t recall the exact moment, since I often find many words by going down rabbit holes. What I do remember though is thinking how “constellation” didn’t feel quite right. A constellation is an officially acknowledged group of stars. In contrast, an asterism is a pattern or group of stars that can be observed by the naked eye. I didn’t grow up with a knowledge of constellations, but like many other people, I have stared at the stars and connected the shining dots to form figures of my own.

“Asterism” felt like it offered a more intimate relationship with the sky, and by extension, the world, and I realized the manuscript was just that. I came to understand the poems as a collection of patterns, personal and collective meaning-making, that arose from living in and reflecting the different countries and cultures I lived with.

That said, I also liked how asterism could mean a group of three asterisks (⁂), which is a symbol used to draw attention to following text, and that it brings to mind a field of aster flowers.

FWR: You’ve had three chapbooks come out in the past. What was that experience like? Did it help you find your readers?

AHL: I ended up with three chapbooks before turning to focus on finishing my first full length, because I often find myself jumping around projects. The result was Bedtime // Riverbed, Dear Bear, and Connotary, which are vastly different from each other; the first consists of Korean folk retellings rippling with “Hanja,” the second is a postapocalyptic epistolary romance, and the third is the chapbook that became the backbone for Asterism.

A backbone in itself is quite complex and beautiful, but with Connotary I started seeing a full body of work forming around it. While I can’t say for sure if I was consciously looking to build myself a platform, putting Connotary together gave me a more lucid idea of who at the moment I wanted to reach the most. Therefore, my hope for Asterism became that it may resonate with anyone who needs to hear that polycentric and transnational lives have a place in this world.

FWR: There are moments in Asterism where you appear to move very deliberately away from sentimentality. The endings of “GREEN CARD :: EVIDENCE OF ADEQUATE MEANS OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT” and “EL MILAGRO :: EDGES” come to mind. How did you arrive at the endings of these poems?

AHL: This is such an interesting question!

I confess there’s a bunch of cynicism in me that I fight against daily. A friend once shared that she mainly had a child leading her heart and an occasional elderly man that sometimes popped his head out to say something grumpy. In contrast, I would say I am mainly a grumpy old woman, but there’s a small poet inside that keeps murmuring “but…”

Even as a child, I felt rather unsatisfied with any perfectly-happily-ever-after I encountered in books. I do enjoy a good happy ending, but I’m suspicious of the perfectly-happily-ever-after, the insinuation that such an ending could legitimize and do away with all the struggles the characters had to go through. I think this translated into some of my poems, particularly the two you have mentioned. I won’t say too much about their endings so as to not impose my own interpretations into anyone’s reading of them, but for “GREEN CARD :: EVIDENCE OF ADEQUATE MEANS OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT” I sought to avoid certainty. For “EL MILAGRO :: EDGES” I thought to address the impossible prospect of fully understanding another’s experience.

The world is messy, and sometimes this can be cause for wonder, but I also simply wanted to acknowledge the very real feelings of resignation, helplessness, and loneliness that we experience as human beings dwelling in what seem like perpetually broken systems. Sometimes these emotions do feel like the end. However, I also like to think the very act of writing in the poetic language is a resistance against letting that “end” have the final word. For me, this apparent contradiction leaves itself open to the possibility of continuation, and hope.

Like yes, “What else could I do?” But… Here I am, writing. Yes, “It’s hard / and not so sweet.” But…!

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview

INTERVIEW with ROBIN LAMER RAHIJA

Robin LaMer Rahija‘s first full length collection, Inside Out Egg, was released in April. Ada Limón writes that “each poem contains the whole unbound strangeness of the human experience–the offhand remark, the blur of being in a body– all of this is written with a humility and understated wit that both growls and sings….” We were thrilled to interview Rahija about her process in crafting Inside Out Egg, as well as the development of this collection’s voice and the nature of the absurd– both in poetry and in the world around us.

FWR: Your poems conduct us into a theater of the absurd where you satirize our fears, our peculiar tendencies and our most ridiculous but touching attitudes. Your voice rings with audacity, and performance, as well as rebellion. When you say, “Something just feels wrong”— about our culture, our lives today, our attempts to find each other, the reader believes you. But, the tender, humorous way your poems express both the wrong and the small touches of “right” give us, your readers, both pleasure and hope in finding community.

I’m fascinated by the short poems that you’ve interspersed in your text that raise mind-boggling questions like “who’s to blame for this bad dream” and comment on the many uses of the preposition “for.” Did you conceive of them as breaks or respites, or did you have other thoughts about their place and placement in your book?

RR: Do you mean the Breaking News poems? The Breaking News poems I thought of as interruptions, like when we’re having a meaningful interaction with someone and the news app on the phone pings with something insignificant, or significant and horrifying, or stressful, and then the moment is gone. I wanted them heavy in the beginning and then to fade away as the book sort of settles into itself and the voice becomes more focused.

FWR: I think many writers and readers, including me, are interested in questions of process. Would you tell us a bit about your process—how a poem begins for you, if there are recognizable triggers; how you develop that initial impulse; how you revise, and so on.

RR: I think about this a lot. It might be different for every poet. It seems like magic every time it happens. Often it’s phonic. I’ll hear a phrase that sounds cool, and it will get stuck in my head like a song lyric. A friend of my told me a story about seeing a fox on the tarmac as they got on a plane, and I’ve been trying to work the phrase “tarmac fox” into a poem ever since. Other times it’s more about just noticing language doing something weird. I was watching the Derby the other day and a list of the horse names came up, which are always ridiculous: Mystik Dan, Catching Freedom, Domestic Product, Society Man. So now I’m thinking about a list poem of fake horse names, or what they’d name themselves, or what they’d name their humans if they raced humans for fun. The trick is training yourself to notice those moments, and also to note them down and not just ignore them.

FWR: Also, to my ear, you have a very strong, confident, even outspoken voice in your poems. One example that caught my ear is your title, “I Can Never Put a Bird in a Poem Because My Name is Robin” and “That Is Not Fair That” voice, to my ear, is quite brave, as well as funny. How did you develop that voice, or was it always natural to you?

RR: No, it’s definitely not my nature. I had to write my way into this voice. I started out writing language poetry that was just pretty sounds with no meaning. I was avoiding writing (and thinking about) the hard things. Writing for me has been a lot of chipping away at my own walls. Each poem too I think has to work on becoming that confident through revision. I don’t want my poems to be complaints. I want them to reveal something, but it can be a fine line. I’m a jangly bag of anxiety most of the time, and I think my poems reflect that. Writing is an attempt to make the jangles into more of a coherent song.

The humor is mostly accidental, I think. Or maybe it comes from an inability to take myself seriously. I do want to get the full range of human emotions out of poetry, and humor is a big part of how we get through the day.

FWR: Who are you reading now? And are the poets you read representative of anything you would describe as “contemporary”? Is there such a thing now? I’m thinking of Stephanie Burt’s essay describing recent poetry as “elliptical,“ meaning the poems depend on “[f]ragmentation, jumpiness, audacity; performance, grammatical oddity; rebellion, voice, some measure of closure.” Does any of this ring bells for you?

RR: I haven’t read that but it feels true for my work. I’m reading Indeterminate Inflorescence by Lee Seong-bok from Sublunary Editions right now. It’s a great collection of small snippets, like poetry aphorisms, that his students collected from his classes. I don’t know how I’d describe contemporary poetry, except it feels brutally personal and outwardly social at the same time.

NEVER ENOUGH by Dustin M. Hoffman

April worked Hector’s hair into pigtail braids. “I fucking love you,” she said and then hated herself for sounding cheesy as bullshit TV, like burnt sugar on her tongue. She’d unplug every TV, yank a million miles of cable wires, just so she could be the only one saying stupid things.

She finished the second braid and told him to take off her underwear. She bit his neck. His sweat tasted metallic, tasted like a fizzed-out sparkler stick. She tugged his hair, wanted to fuck as hard as hating her town called Alma, as hard as hating her parents and their house served with eviction and this winter and this world.

“Someone’s watching,” Hector whispered.

Behind her, some horror was playing out: Her father waving a claw hammer. Or it was her mom, who could do nothing but gawk and worry. The queen of the crumbling castle.

April pulled on her jeans. Outside the door she’d left cracked, slippers shuffled against linoleum.

“That fucking weirdo.” She pulled an inside-out Suicidal Tendencies T-shirt over her head. “She just stood there watching.”

“What should she have done? You want her to yell? Or, what, slap you?”

“Yes,” April said. “Fuck yes. That would be doing something at least.” She felt her face reddening down to the freckles on her chest.

“She’s losing her home, too,” Hector said.

“Why are you taking her side?”

She sat on the edge of her bed, back to him. She wished he’d tuck her body against his again, but not fucking this time, just staying close.

The bedroom door swung all the way open. April’s little sister tromped into the room. She wore royal blue gym shorts and a white tank top. Her hands were wrapped in fingerless red-leather fighting gloves, and she had a shovel slung over each shoulder.

“Mom says you need to help.”

“Jesus, Elise. Know how to knock?” April passed Hector his underwear. “How about everyone just comes into my room to stare.”

“She says I gotta dig, and I said, bitch, if I gotta dig so does April and her screw buddy.” Elise’s leather knuckles pushed a shovel at April.

“Why aren’t you in school?” April asked.

“School’s been over for like an hour,” Elise said. “Where were you?”

“I’m done with that place. What’s the point?” She’d skipped the last three days, and she might never go back.

“Is that Hector?” Elise’s shovel tracked down his neck to hover over his heart like an accusation.

“Who the hell else would it be?” April said.

“I’ve never met this dude. How do I know?”

April snagged the shovel out of her sister’s hand. “No one meets anyone around here. Might as well hide from the world like Mom.”

“Not me. I’m taking shotput all the way to a freeride from some sucker college. Then I’m going to fight as many bitches as I can knock out until UFC starts up a league just for me.”

“You’re a moron if you think anyone’s going to give you anything for free,” April said.

“Maybe UFC will broadcast me kicking my sister’s ass.” Elise shadow-boxed jabs at April’s stomach. She finished with a fake palm-heel aimed at her nose. April didn’t flinch. She rolled her eyes and drove a shovel spade into her bedroom floor, chipped it because it meant nothing, because soon some other assholes would own it and now, they’d own this scar too.

*

Outside, April watched Hector and Elise foolishly pang shovels against frozen dirt. Elise stabbed with rhythmic violence. This was just another workout for her. Hector hopped on his shovel and struggled to unearth more than a frozen shaving. No one had any idea where to dig. For years, their mother had buried cash. She’d slip slim rolls of tens and twenties from Dad’s wallet and into Campbell’s Soup cans and empty shampoo bottles. Then she’d bury them in the backyard. Dad used to laugh about it, told them it made Mom feel safe. Besides, Dad would say, we have plenty of money so long as houses need painting and I have hands to swing a brush. That had been true in the fat summers, when just enough paint peeled off rich people’s siding to pay the bills.

“Why isn’t Dad helping?” April asked.

“Gone-zo.” Elise shovel-stabbed the earth. “He’s working.”

Their house was sided in vinyl. April’s dad installed it himself, was proud his own house would never need paint. Her dad had bought this riverfront one-story after the flood of ’86. They couldn’t have afforded it if the basement hadn’t filled with water and mold. Dad installed a sump pump in the basement and, at the age of five, April had helped tear the moldy walls down to studs. Gutted and born again perfect, he liked to brag. This was their house. Except it wasn’t anymore.

“It won’t be enough to stop anything,” April said. “Neither will this.”

Elise’s shovel clinked and she dropped to claw out a rock. She rolled onto her back and chucked the rock at the iced-over river, then did twenty push-ups before she resumed digging.

After a few minutes of digging ice, April gave up. She tried to remember watching her mom dig in those summers before she stopped leaving the house altogether. Through the window, she’d be wearing hideous gingham dresses she sewed herself. The ankle-length skirt would be crusted in mud, her pits sweat darkened. She’d wave at her daughters spying through the window, the setting sun and river twinkling at her back. She was beautiful, sure, but beautiful didn’t stop her from getting crazier.

April javelin-threw the shovel back toward the house, where her mom now watched from the window’s yellow kitchen light. April hoped she hated herself for burying all that money. She hoped she felt like dirt for not helping, for being helpless. She was probably thinking about the move, trying to calculate how she could seal herself inside a cardboard box so she wouldn’t have to encounter the outside world. Locked in a box would never be April’s way.

Hector was still at the same spot, still digging straight down when April touched his shoulder. “Let’s get out of here before you hit a gas line.”

“I think I’ve almost found something,” he said.

“Let’s go far away, somewhere no one we know has ever been.”

“Almost there. See.” Hector’s shovel spade dredged up tiny crumbles. There was nothing to see.

“Let’s steal my dad’s truck, then fuck and drink and do whatever we want without anyone watching.”

“Or we could stay.” Hector chuffed steam breath.

“He find something?” Elise pirouetted into more shadowboxing aimed at Hector’s sunset-stretched shadow.

“Almost,” Hector said. They both stared into the nothing hole.

“Let’s go.” April tugged Hector’s jean jacket. The sun was almost down, but they could still ride into it and turn into balls of fire.

“Quit nagging him, bitch,” Elise said.

“Quit encouraging this ridiculous shit.”

“Quit bitching about every little bitch thing.”

April slid her leg behind Elise and dropped her. Elise popped back up and tried for a headlock. Then they were both on the ground, and April felt how small her tough-as-nails little sister was. Elise didn’t understand how she couldn’t win this fight, how they wouldn’t find Mom’s money, how their home was already gone. Elise was making muscles and dreaming big and half of April wanted to punch all the hope out of her twerp face and the other half wanted to hug her so close.

“There we go.” Hector dropped to his knees, reached bicep-deep into his hole. April expected another rock, but Hector lifted a can of tomato soup. He held it up against the last sunlight. It was poisonous hope. If they dug all through the night, they wouldn’t find another. Elise counted out each of the thirty-six dollars with a yell that sailed across the river. Hector and Elise clinked shovel spades together, and then Elise ran the can into the house.

“I told you I’d find something.”

“Stupid luck,” April said.

“We can go now.” Hector was beaming. “I won.”

“My fucking hero.” She smiled too. But she was becoming as frozen as the ground, every petty treasure buried and irretrievable.

He jogged into her house, didn’t even notice she stayed outside to kick dirt into Hector’s hole, patching up the lawn nice for whoever would own the house next.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Fiction, home

ECOPOETRY FROM JAPAN with Ryoichi Wago and Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FOUR POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

by Judy Halebksy

Ayako Takahashi

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

MONTHLY with Alexander Duringer

Alexander Duringer is from Buffalo, NY and earned his MFA in Poetry from North Carolina State University. He is a winner of the American Academy of Poets Prize as well as the Bruce & Marjorie Petesch Award. In 2022 he was a finalist for The Sewanee Review’s annual poetry contest. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Plainsongs, Cola Literary Review, The Seventh Wave, The Shore, and Poets.org. He is interviewed for Four Way Review by Matthew Tuckner.

FOUR POEMS by Alexander Duringer

INTERVIEW WITH Alexander Duringer

AN ENGINE FOR UNDERSTANDING: AN INTERVIEW WITH Willie Lin

Willie Lin’s debut poetry collection, Conversations Among Stones, will be published in November 2023 by BOA Editions. Simone Menard-Irvine interviewed Lin for Four Way Review.

FWR: I would like to start out by first asking about what it’s like to be publishing your first full collection of poetry? What was the process of writing and assembling like in comparison to the publication of your earlier chapbooks?

WL: My urge in assembling manuscripts is always to pare down. Because of this impulse, assembling my chapbooks felt like a much clearer and more straightforward process. For the manuscript that became Conversation Among Stones, I struggled with holding it in its entirety in my mind and had to be more deliberate in my approach. I understood how certain constellations of poems fit together but was a bit overwhelmed with shaping the manuscript as a whole. At one point, I actually made a spreadsheet of all the poems that I thought might belong in the book and notated and ordered them according to a few different axes to help me see how they might fit together.

FWR: Your title, “Conversation Among Stones” brings up questions of action between the inanimate. What inspired you to frame your collection under this title?

WL: That idea is definitely part of what I had hoped to evoke with the title—of speaking to the inanimate and what can’t or refuses to speak back, of language spanning, filling, straining, or distending across gaps, of failing to say or hear what matters. I think these intimations are a good way of entering the book, which I hope worries and enacts some of these concerns regarding the capacities and limitations of language.

FWR: My next question is in regards to the variations of length in the poems. In “Dear,” which is only two lines, you write “A knife pares to learn what is flesh. / What is flesh.” Both a statement and a question, you ask the reader to consider something so simple, yet laden with ideas regarding the body and violence. What was your process in developing these shorter pieces, and how do you see them functioning within the broader collection?

WL: Poems can beguile in so many ways, but I’ve always loved the compactness of a short poem. Part of it is how easy it is to carry them with you in their entirety and turn them over in your mind. Since I first came across Issa’s “This world of dew / is a world of dew. / And yet… and yet…” in a poetry class almost 20 years ago, I’ve been able to carry it with me. I’ve learned and forgotten countless things in poems and in life in the ensuing years, but have kept that poem almost unconsciously, without effort. Another aspect of short poems’ appeal to me is the paradoxical way time works in them. A short poem’s effect feels almost instantaneous because of its brevity but time also dilates across its lines. The duration seems somehow mismatched with the time it takes to run your eyes along the text. In Lucille Clifton’s “why some people be mad at me sometimes,” the body of the poem answers the charge of the title in five short lines:

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine

That last one-word, monosyllabic line, especially, seems to take forever to conclude. The compression of the poem—the words under pressure from the wide sweep of white space—exerts a redoubled, outward pressure and reverberates.

My poem “Dear” started as a longer poem (not longer by much, maybe 10 lines or so). At one point, as an experiment, I took out all the “I” statements in the poem and arrived at the version that exists now. Often, that’s how it works. I try different approaches and revise, sometimes rashly and foolishly, until something jostles loose. When I finally got to the two-line version of “Dear,” for me, the fragmentary nature of it fit with the precarity of its assertion and question. How the shorter poems appear on the page also matters in that I wanted the blank expanse that follows the poem to function as an extended breath. Because the book proceeds with no section breaks, it made sense to me to vary the lengths and movements of the poems to establish a kind of cadence, a push-and-pull.

FWR: In thinking about the themes that circulate throughout your work, a couple of specific ideas stand out as particularly potent. One is the issue of memory; the violence, complexities, and confusion of your past run their threads throughout the collection. In “The Vocation,” you write, “In the year I learned / to cease writing about history / in the present tense, / I was the silence of chalk dust, / of brothers.”

It seems like history, for the speaker, is something to be dealt with, instead of accepted unquestioningly. What does writing about the past, be it in present tense or not, do for you as an individual? Does confronting the past through writing work as a catharsis, a way to process, or does it instead serve as a conduit to expanding upon the ideas you wish to convey?

WL: I think memory—and the process of remembering—is an engine for understanding and, by extension, meaning. For experience to make sense, we have to remember. Knowing or thinking can’t really be separated from experience. It’s also true that memory, personal and communal, is restless and malleable. I have an image of the past as a landscape of sand dunes. The shapes drift. They slip, they resettle. How things feel in the moment can be one kind of understanding, how we remember them, how they shift, linger, rise, how they appear in the context of things that have happened since or what we do not yet know are other kinds.

In Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay,” when challenged on why she remembers “too much”—“Why hold onto all that?”—the speaker responds, “Where can I put it down?” I suppose poetry for me is one place to put it down. (Though I don’t think I could be accused of remembering too much in life. I have a terrible memory.) In writing a poem, I’m making a deliberate attempt toward an understanding, however provisional. Poems are good spaces for holding and turning, for thinking through and imagining, for venturing out—and that is the final, extravagant goal, to reach out and connect with someone else. In my poems, I want to make a path that leads inward to the center—and out.

FWR: In that same poem, you confront another central theme: men. When you mention men, they are typically described via their participation in fatherhood or brotherhood. You write, “the men/slammed the table when they laughed/at their circumstance, or drank/too much to learn what it meant/to have a brother, or were true to/no end, or tried to love their fathers/before they disappeared into/hagiography.”

Masculinity here seems to be defined as a relational identity, one that is constituted by lineage and socialization. I would love to hear you speak on your relationship with gender norms and roles, especially in your writing.

WL: This question is particularly fascinating because I can’t say I conceived of my poems working together in this way, even though of course you’re right to point to how often these types of familial terms come up. I suppose part of the answer has to be how the poems relate to my autobiography. In my family, my mother is the only woman in her generation. She has two brothers and my father has two brothers. I’m also the only woman in my generation. I have three cousins, all men. I’m an only child who grew up in China during the one-child policy, so all around me were lots of children just like me, who’ll never know what it means to have a sibling. I felt a bit of an outsider’s fascination with those types of relationships and inheritances, especially as I got older and became more aware of the other social forces at work that historically favored sons. I think poetry can function partly as personal interventions in cultural history and memory, holding the ambivalences, contradictions, and idiosyncrasies that live at those intersections.

FWR: We see many instances of place in relation to memory, but there are only a few instances in which those locations are given a specific name, such as in “Teleology” when you mention Nebraska. Can you walk us through your approach to location in your work and what places need an identifier, versus places that can exist more specifically within the speaker’s domain of recollection?

WL: I think generally the idea of dislocation is more important than the locations themselves in terms of how they function in the poems. Saying the name of a place evinces a kind of ownership of or intimacy with that place. For many of the poems, in not naming specific locations, I more so wanted to evoke a sense of rootlessness and for the intimacy to be with the speaker’s uneasiness within or distance from those places. “Nebraska” in “Teleology” is a departure from that model not only because it offers a specific name but also because I think in this instance Nebraska is not a real place but an imagined one—a kind of projection that stands in for other things (the poem says, “like Nebraska,” “many Nebraskas,” “Nebraska is a little funeral”—my apologies to the real Nebraska!).

FWR: In “Dream with Omen,” you end the piece with “I would like to rest now / with my head in a warm lap.” This is one of my favorite lines, because it both speaks to the sound and feel of this collection, and it interrogates the two balancing aspects of this collection: that of memory and the mind, and that of the physical present. The speaker in many of your pieces seems to be constantly grappling with the subconscious world, made alive by dreams. How do you view or negotiate the separation and/or melding of the subconscious and the “real” world? Does the mind and its preoccupation with the past stop the self from fully engaging in the present? Can the speaker rest in a warm lap and still accept the darkness of the subconscious?

WL: In putting together this book, I became conscious of how often I write about dreaming and/or sleeping. I felt sheepish both because we are told often (as writers and as people) that dreams are boring and because maybe these poems betray my personal tendency toward indolence.

It’s interesting to align the past with the subconscious and the present with the “real” as you do in the question. I do feel the tension between those things in writing even as I also feel that thoughts are real and fears are real, etc., just as senses—how we experience the physical world—are real. And it feels a little silly to say this but I have a kind of faith that our subconscious is working away trying to help us come to terms with what occupies us in the real, present world even as we sleep and dream. Everyone who writes has at times had that sense that what they are writing is received, as if they are tapping into some other world or force. Maybe that idea is analogous to what I mean.

Memories, dreams, the subconscious, however the particularities of the mind manifest, feel consequential in their bearing on lived experience—they are how the real world lives in us. There is no unmediated world. Or if there is, we don’t know it. We must encounter the world personally because we are people. All this is to say I’m still learning line-to-line, poem-to-poem how best to articulate that kind of interiority in a meaningful way, without leaving the reader adrift. Leaning on dreams can make a poem feel muted and entering memories can feel like putting on the heaviness of a wet wool sweater and those things do not always serve the poem. I hope for my poems’ sake that I get that balance right more often than not.

Willie Lin was interviewed for Four Way Review by Simone Menard-Irvine.

Simone Menard-Irvine is a poet from Brooklyn, New York currently pursuing and English degree at Smith College. Her work has been published in HOBART and Emulate magazine.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview

BEST OF THE NET 2023 Nominations

POETRY

ROBE AND HELMET BAG by Tommye Blount

COSMOLOGY by Sasha Burshteyn

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT UNSONNET by Dante Di Stefano

DEATH IN SPRING by Mónica Gomery

DETROIT PASTORAL by Brittany Rogers

AFTERMATH by Robert Wood Lynn

FICTION

WET OR DRY by Naomi Silverman

- Published in home

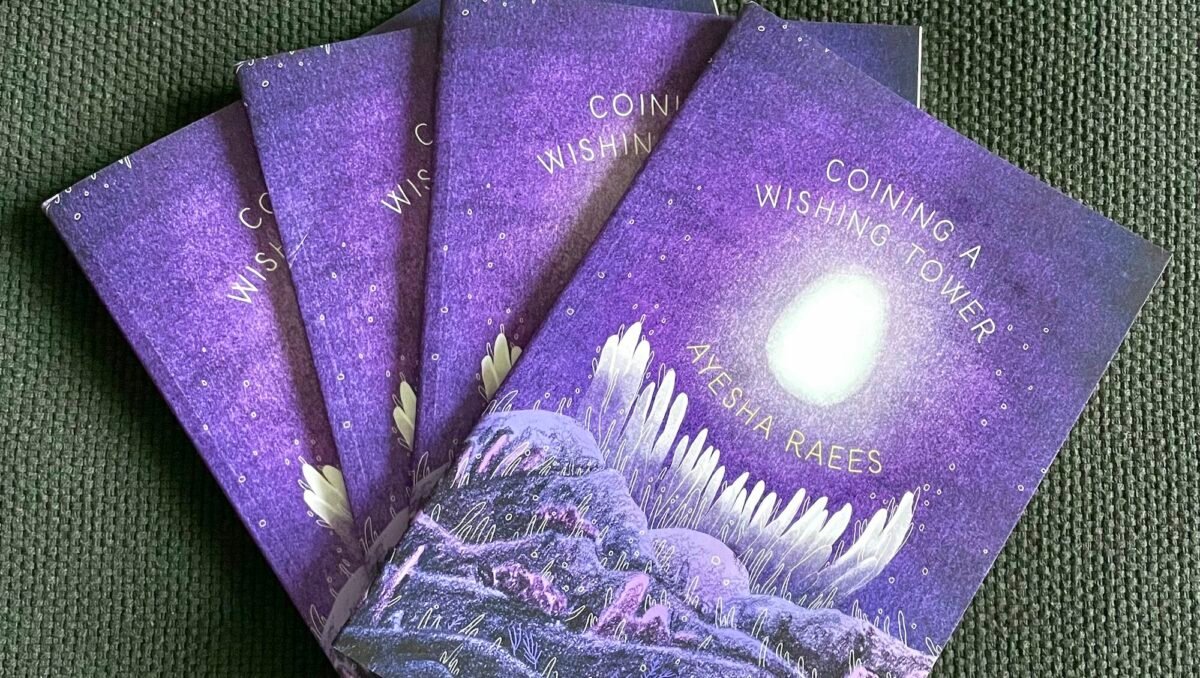

INTERVIEW WITH Ayesha Raees

Ayesha Raees’ fabulist and fable-like chapbook, Coining a Wishing Tower (Platypus Press Broken River Prize winner, 2020, selected by Kaveh Akbar), is composed of 56 prose-like blocks—give or a take a few half-fragments.

These prose-poems, which are whimsical, profound, vulnerable, and full of pathos, grief, and transformation, depict complex relationships between parents and child, religion and women, lovers and the beloved, wishers and wish-granters. There are three separate narrative strands, teleporting between Pakistan; New York City; Makkah; New London, Connecticut; as well as more abstract spaces, like a Desire Path, as well as Barzakh (which, the chapbook tells us, Google calls a “Christian Limbo”).

The first narrative involves House Mouse, who climbs and climbs until the “end of all possible height” and finds itself in a wishing tower which can grant all its wishes. House Mouse performs various rituals including the ritual of death—in which both House Mouse and the tower die. The second strand, taking place in a wooden house in New Connecticut, involves three characters: Godfish, a cat who is in love with Godfish, and the moon, who is also in love with Godfish. And finally, there is the more realist narrative strand, with a female speaker—a daughter and an immigrant—who seems to speak for Raees herself, and her own personal experiences with family, religion, migration and displacement.

She is interviewed here by Cleo Qian, previously published in Issue 25.

CQ: How did you come up with the characters of House Mouse, the tower, Godfish, the cat, and the moon?

AR: Each character in the book embodies, not always wholly or too literally, a person of importance from my life. The book itself was conceived the night that I found out my best friend, Q, was in an irreversible coma due to a (eventually successful) suicide attempt. The characters in the book are my own reckoning with the different facets of the deaths we face in our lives before our eventual, more literal, ends. But I did not want this book to be so linear or literal; I wanted it to tackle death in varying ways.

House Mouse represents every young immigrant. Immigrants must leave their “selves” or “homes” for a better future, which is the mirage of the “American dream”—which calls for outsiders to come in and fill the gaps of a decaying system. Asian immigrants also, in many ways, are pressed for success or “height” to obtain ‘value’ from a very young age.

As a poet, “House Mouse” is also a play on words. What happens to a common house mouse when it is without a house? What happens to a young immigrant when they leave their homes for the world’s seductions?

The wishing tower is a symbol of the Ka’abah but is also something of extreme physical height, an unreachable thing. “Coining” in the collection’s title reflects stoning—a visual gesture, with prayers or wishes. Godfish is a play on goldfish, but this character also represents another close friend of mine, A, who was another young immigrant who left home to America to pursue another life and was lost in a tragic way. And the cat and the moon are, at the end of the day, spectators, both holding power but choosing to practice it in different ways; they are two faces of a white savior complex and American passivity.

I don’t believe I would have been able to say all I wanted to say without the aid of characters in this book.

CQ: Let’s talk a little bit about the settings mentioned throughout the book. What is the significance of the setting New London, Connecticut? Early in the book, you write, “I have never been to New London, Connecticut.” In the narrative of the Godfish, cat, and moon, New London is both real and unreal, and the wooden house they live in is centric to “unnatural happenings” and set apart from the “real life giant black road.” And what about the sites of pilgrimage throughout the book? Is America also a site to make a pilgrimage to, or is it a place to escape to?

AR: I have a love for places and the social cultures they inevitably hold. I am someone who has been in constant movement her whole life, and I believe places to be their own characters, to have their spirits. Therefore, the different locations in the book are all real, even the unreal ones. They are their own breathing, living organisms.

And that’s how New London, in Connecticut, feels to me. I have never been. In the book, it is a place of “unnatural happenings” as, just as written in the book, it is a place where Godfish died.

The character who is embodied in Godfish was my high school best friend, A. He went to Connecticut College (in New London, Connecticut) and was hit by a drunk driver while he was crossing the road at night to go to his dorm. The drunk driver, instead of calling for help, pulled A’s body aside and drove away. Leaving him. Right there. To spend a cold December night outside. He was found the next day. His date of death is merely an estimation.

I was myself a sophomore at Bennington College when I received the news. This was December 2015. I was devastated. Over the years of grieving, New London, Connecticut became a significant image for me. The side of the road A was on was very real. I don’t know what it looks like in real life. But in my head, there is a whole image. I live with the happenings of that night every time I am grieving. How can I have such vivid imagery exist when I was not even physically present? That’s the power words have over me.

The moon that captures and cannot fully lift Godfish embodies “moonshine,” intoxication, which failed both Godfish (and A). In the end, my friend was a gold marking on the road. And I believe when I started to write about Q [my friend who passed away after being in a coma], A came forward into the poetry as well. They both took me on the journey of characters and settings, and the book’s narrative reckons with all our losses and its impact.

Is that a sort of pilgrimage? I believe so.

CQ: The book opens with House Mouse climbing and climbing until it gets to the wishing tower. Godfish wishes to be able to swim to the sun, its beloved. The moon wishes to draw Godfish to itself. In Islam, Jannat-ul-Firdous, we learn, is a “place in heaven that is of the highest level, reserved for the most pious, the most special, the most loved.” Do you think the striving for height is a universal human desire? How do height and religion intertwine?

AR: Who are we but an accumulation of our wantings? Humans have inane, uncontrollable, desires that make us get out of the ordinary and strive for something that can give us, even for a single moment, a rich breath of fresh extraordinary. To be human is to be full of wanting, to exist in that kind of inevitable strive. And that kind of striving will always achieve some kind of height.

But my goal through the book, and of course for my own reckoning as a young ambitious Asian immigrant in the American landscape, was to ask what those systems of value ask of us. These “heights” we climb to that are a measure of our worth, giving our human life a value. In order to have value, we keep climbing. But until when?

I was thrown into this disarray because Q and I were ambitious young Asian women from so-called “third world countries” and quite alike in our dispositions. We wanted to be accomplished. To have value as individuals and not be reduced to our Asian womanhoods. But that striving killed us. I watched her fall. And I found myself falling. Like most Asians, we were sold to ideas of hard work leading to value, such as our grades, the length of our CVs, the honors and fellowships and residencies and awards. We were accomplished. But we did not have enough value to win the system that was built against us.

So what did we strive for?

As I was grieving, religion became my literature and God my mentor. I grew up with Islam but as with most religious countries, religion seeped in as a way of life rather than a radicality. Islam is a part of my cultural identity. It is part of my language. Islam is a constant reminder of how to live a life that prepares us for death. And even though I am (and was!) so young, to be handed so many deaths of so many loved ones left me in disarray. I was alone in the American landscape without much support or, as we all have experienced our capitalist systems, empathy. When I finally turned again towards Islam, I was looking for some sense that the West, and Western literature, could not afford me.

I will always say that I am not a religious person. After all, religion is a tool to control the masses. I don’t want Coining A Wishing Tower to be a religious book. I am, however, deeply spiritual. I do have faith in the unknown. I do believe in a God. Maybe when I am brave enough to proclaim it externally, I can even say my God. I have belief in the many rituals that help us decipher the literals of our lives towards a healthy figurative. A true kind of poem. It is inevitable for me to not see God with poetry.

CQ: Many of the prose poems—and the arcs of the House Mouse, the tower, the Godfish, cat, and moon—are written in a parable-like tone. Some of them also verge on fairy tales. You have such wonderful lines and imagination when, for example, House Mouse is cooking in the tower:

“House Mouse cooked fish for the first meal, corn for the

second meal, and melted cheese for the third meal. The

tower is one room full of great imaginings working towards

not staying imagined…”

Or when the moon tries to bring Godfish to itself:

“With every mustered strength, the moon lifts the water, rounds

Godfish into a dripping ball and pulls it through the opened

window only to bring it to a float and a hover in the storming

snow of New London, Connecticut….”

What was the influence of parable and fairy tale in your writing of these poems? Do you consider these narratives allegories?

AR: I celebrate poetry because a good functioning poem has great intentionality. If you spend enough time even with a single line, you can see how the poet has chosen to lay the words next to each other the way they are. Nothing is random. And everything adds to something else.

I do a lot of work with symbolism and imagery, often lent from my own life. I am always in awe at the contrast and the magic I see in front of me. For example, I am currently in Paris, sitting in a gorgeous reading room at Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Public Library of France) answering these questions, where I find myself watching a parade of silent children running through the rows of hunched working adults. They are not laughing. Or making any kind of noise. They are just running through the gorgeous rows of tables. What a contrast! What image and magic! And hardly anyone is looking up! Doesn’t that feel like a fairy tale? Or an allegory? Children running through a grand beautiful reading room of a world-famous library full of frowning adults?

I do the same in the verses you have pointed out. When I put [these contrasts] of the imagined and unimagined together, I surprise myself.

CW: Do you believe in epiphany? How does epiphany play a role in these poems?

AR: I believe in wonder, which can be quite like epiphany, but is not always the same. Epiphany feels like a lightbulb moment of occasional discovery, but wonder feels like a series of discoveries that were always present but are now fully being seen.

In this way, the form of the book holds a kind of wonder. It is an epic told in fragments. Even though I wrote it linearly and the editorial process did not include rearrangements but just clarifications, I saw how one narrative thread began to breathe while still supporting the other threads.

When I read the book out loud in readings, I flip through the book at random and read pieces from it. I am faced with more wonder in this as well.

CQ: Google is also frequently cited throughout the poems. Often, Google’s word is taken as factual and fills in missing gaps in the speaker’s knowledge—e.g. Google speaks on the status of New London, Connecticut, as a small city; on how many lives cats have; on what Islamic Barzakh is. Why did you invoke Google and what is the role of human technology in understanding these characters and poems?

AR: Isn’t Google some form of god now? We rely on it for all our small and big questions and immediately believe what it tells us. “Google says…” instead of “God says.” I find in both these common phrases a kind of significant mimicry.

In a past that’s not too far off (I am thinking of my parents’ lives), information was not accessible at all. My parents were probably faced with so much unknown but still had to strive forward with whatever understanding and skills they did have. They couldn’t just Google how to exactly use a new microwave they bought or how to apply for a visa to travel. In these observations, Google has become such a huge part of our contemporary lives that without it, we wouldn’t often know what to do. And with it, we often are also told how to live a life and exactly what to do.

Maybe I wanted to have Google in the book because so much of our consolations and salvation hinges on asking. In the past, we sat in prayer and asked. And now we get on our phones, maybe our hands poised ritually the same, and ask. We get answered in both ways. We believe. And sometimes, we don’t.

CQ: Another theme that pops up in the latter half of the book is forgetting. Of the Islamic heaven, you write, “Any kind of remembrance of our past lives, any regret, every love, it will all be flushed.” You, the speaker, ask if you will be forgotten on the day of judgment, and the mother says, “It’s inevitable…you will forget me too.” When the cat finds Godfish, dead, you write, “Would death tear them apart to a degree of absolute forget?” These lines really tugged at my heart. The fear of forgetting my loved ones after death is terrifying . How are these poems a response to the question of whether death is the ultimate forgetting?

AR: What we don’t remember also brings us relief. That’s the concept most Muslims have about death and afterlife. If I don’t remember the extent of love I feel for my mother, I would not feel the extent of her loss. I would be relieved of grief and the pain of it.

This is scary. But also, to some degree, comforting. There is consolation in thinking we won’t always be yearning for the ones we lose.

I have tried to tackle the question of love and endings through the poems in small and big ways. The last prose block of House Mouse “returning” holds that life and death can exist in mimicry. But what bridges each ending with another beginning is change and transformation.

CQ: There are a series of transformations: Godfish into a fish, the wishing tower into a pile of rubble. Are these “failed” transformations? Are they an inevitable part of the cycle of life?

AR: I don’t believe in “failed” transformations, and I think maybe that was what I was trying to truly say throughout this epic. Even though Godfish loses its God-ness, its existence still transformed the moon and the cat. The wishing tower is no longer able to grant wishes, and then it loses its life. But it transforms into something else, even if that is rubble which will erode away.

These losses are, in some ways, an indication of life’s inevitable end, yes, but [writing this book] also gave me the gift [of knowing] that there will always be some kind of other journey. Any end we think of is a ripple effect towards something else, beyond comprehension.

These fragmented thoughts are captured in the fragmented poems. We can see the “afterlives” of House Mouse, the Godfish and the tower. [I wanted to show how] there is never any true failure in our conventional ideas of failing. Things that “fall” fall to somewhere else.

CQ: Do you consider these poems of loss?

AR: Absolutely. But not only. These poems are full of grief. But also consolation. Also philosophical nurturings. They are an encouragement to move away from our unconventional thinking of the most universal experience of loss itself.

CQ: At the end of the book, House Mouse is somehow resurrected. I loved this ending, which felt joyous, miraculous, and yet also sad and full of grief because there is no one around to meet House Mouse. What are we to make of House Mouse’s return to life? What is House Mouse returning to?

AR: House Mouse holds huge parts of me as well as huge parts of the speaker, which, of course as poets say lingo, is both me and not me. The speaker leaves home, Pakistan, and goes to America, fulfilling her teenage dream to leave, but the speaker also returns. And with every return, there is change. Decay. Death. Loss. Transformations.

And each immigrant really asks these questions if they return [to where they have left]: “What am I returning to?” “What makes life life here and how much of it I have left?” “Who waits for me and who could not?”

“What has died and what still lives?”

Returning is hard. It is full of lamenting and an inconsolable feeling. We have to reckon with the relativity of time, the loss of romance, and changes that override our initial memories. House Mouse finally returns to the home which it left in the first prose block of the book. But so much has changed. What is home now?

I think there is consolation and love in the fact that we have our return. Even if our parents die. Even if our houses change. Even if the furniture gets full of dust. Just because there is this kind of loss, does not mean we do not feel all the presence of what home is there. Maybe, in life, forgetting can relieve us of pain, but remembrance reminds us of the original love we were given, however much it has been transformed.

CQ: You published Coining a Wishing Tower during the lockdown. Where were you, location-wise, when you heard that your book was accepted for publication? How did COVID-19 affect your experience writing and publishing this chapbook?

AR: This is actually a funny story. The day I got the email that I won the Broken River Prize from Platypus for the book was also the day Biden won (or, well, Trump lost) the elections—November 7 2020. We were all under strict Covid lockdown, but because of the election results, the streets of Brooklyn were flooded with cheers and shouts and music. We all ran through the streets. In that way, I felt I was also celebrating my own little win of accomplishing a dream (the wish I had coined a long time ago). The book was mostly written in 2019 around the loss of Q. But this book definitely was a huge victim of the pandemic aftermath. What with delays in publishing and then my press’s bankruptcy, my book only had a life in this world for one year. But I believe in its return. The life after its life.

CQ: What’s next for you?

AR: Even though I often fail to keep it as simple as the words I am about to say, all I truly desire is to keep writing. I am deeply in love with poetry. And I don’t think this affair will end at all. I am hoping to keep at it and, in small and big ways, keep being read.

To more poems! To more books!

Ayesha Raees عائشہ رئیس identifies herself as a hybrid creating hybrid poetry through hybrid forms. Her work strongly revolves around issues of race and identity, G/god and displacement, and mental illness while possessing a strong agency for accessibility, community, and change. Raees currently serves as an Assistant Poetry Editor at AAWW’s The Margins and has received fellowships from Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Brooklyn Poets, and Kundiman. Her debut chapbook “Coining A Wishing Tower” won the Broken River Prize, judged by Kaveh Akbar, and is published by Platypus Press. From Lahore, Pakistan, she currently shifts around Lahore, New York City, and Miami.

AXOLOTL BY ANTHONY GOMEZ III

When wildlife conservationists released a dozen axolotls into the waterways in an abandoned town not far from Guadalajara, they were surprised to see the pink salamanders swim within the water for less than a minute. The endangered creatures jumped out of the pool on their own.

Eleven of them moved to the side and chose to die rather than learn to live again in this human-created habitat. Their smiling mouths stayed that way as they flopped along the dirt. Meanwhile, the last survivor came out of the water. It regarded its dying friends and marched down the road. The conservationists could not explain what was happening, but this last axolotl popped into a stranger’s home and, though they later tried to find it, they could not. The attempt to save the species was deemed a disaster.

*

Some years ago, on a flight from Tokyo to Guadalajara, I gave in to the cardinal sin of air travel—I spoke to a stranger. In the middle of the flight, when all those around me were asleep, I saw a slow set of tears fall from a Japanese woman’s eyes and disappear into her jeans. Hours to go, the short aisle between us was an insufficient chasm. I could not ignore the scene. So, I asked her what was wrong, and she confessed in carefully selected English that she was on her way to bury her son.

“But I’m not blaming Mexico,” she pleaded, as if I thought she was the type to blame a whole nation for a single incident. “He loved the country and the cities. Never had a bad thing to say.”

“What did he do there?” I asked.

“He learned to cook. He studied the cooks in the kitchen and the cooks in the home. Always, he said, Mexico produced the greatest food. He wanted to know why; so, he moved there the moment he became an adult. Would have been three years in a couple of days.”

“I think I would agree with his assessment. It’s a wonderful food culture.” The way I said it, with a remove and a distance, must have exposed my relationship to the country as also removed and distant. She had a wrong initial impression.

“Oh, I’m sorry. It’s terrible. I assumed because of your being on this plane and your…your look…you were from there.”

“I have family and friends I visit in Mexico. But no, I’m not from there.”

“It’s terrible of me,” she said. “I could have asked. I’ll…I’ll do that now. What takes you to Mexico? Those friends and family?”

“A cousin of mine passed away. One minute Alfonso was talking, then someone noticed him stutter. His heart was giving out. Then, it did.”

“Seems the airline put the grievers together.”

I looked around. We were the only ones awake. She might have been right.

“Weird, isn’t it?” she wondered, aloud. “To be on a flight to claim a dead body? I have never been to Mexico, and the moment I go it’s because I am on my way to see to my son’s death.”

Strange way of putting it, I thought, but she was right about it being weird.

Alfonso was a favorite cousin, an adult while I was a teenager and a teenager while I was still a child. Separated by less than four years, our minor gap in age nonetheless left him wiser and more experienced. When he was around, I ran to him for the sort of advice one is ashamed to steal from parents. He was dead at thirty-two and it seemed I’d lost a lifeline. Navigating a future without his guidance left me feeling adrift.

“We don’t need to speak about our dead,” she said. “One should remember them while one is happy to remind oneself they’re gone, or when one is sad to remind oneself of what one had.”

If that was true, then which emotion was she experiencing? What attitude toward her son possessed her that she preferred to think or speak less about him?

“Did you enjoy Tokyo?” she asked.

“It was a disaster of a trip, I’m afraid. I never saw it.”

Disaster was an adequate term. After a fourteen-hour direct flight, I’d landed in the airport, found the exit, and noticed on my phone’s home screen a long list of missed calls and texts. I sighed as I listened to each voicemail, and as I read each text. All of them were variations of the same sad news. I went to the bathroom, found an empty stall, and started to cry. I let that pass and then found a flight out.

Nine months of planning and fighting for this trip fell apart. It was a fight to get the time off from my data entry job, the courage to do it, and the money for two weeks abroad saved. While the first requirement wasn’t initially approved, a set of company layoffs I couldn’t escape made it all possible.

I booked the trip for no purpose other than a want to get off this continent. I suppose what I wanted more than anything was to go somewhere I could be lost, where I did not speak the language, and where I did not possess an overshadowing familial history dictating each sight or town. My journey was to see how I would adapt to a different culture—and if I could. When I called Alfonso to tell him about the trip, he described his favorite film Ikiru and said I should search out locations from the film. I didn’t bother to argue most of the film was shot on soundstages. I replied that my knowledge of Japan came from horror films and books by Ryū Murakami and Yoko Ogawa. None of those, I prayed, were accurate precursors to my trip.

Alfonso had not traveled much within Mexico, or outside of it. But there was one story about Japan he could share. He once heard reports of travelers who visited. The first Mexicans to the country reported arriving on the land, journeying from one place to another, town to town, until suddenly, they were unable to continue along a path. Blocked by a wall which could not be seen. Some claimed the wall was the product of spirit. Some said the travelers brought this fate over, and others said it was a uniquely Japanese magic. They learned there was one solution. Secrets could bring the walls down. The travelers had to give some truth about themselves up, else their journey was over, and they had to return home.

“Did they give up a secret?” I asked Alfonso.

About to tell me, Alfonso stopped to laugh, and suggested a different ending: “Would you?”

I did not explain my relationship with Alfonso to her. No, she wanted to get away from grief. We moved on to different topics with ease—like a spell had fallen upon us. So few people in life make conversation easy and pull from your soul the language and books and narratives you want to share. I almost lamented losing her to the nation once we landed. Even now, for comfort, I can close my eyes and imagine her listening as I confess my troubles and dreams. On that plane, in hushed voices so as not to wake anyone, we ceased being strangers.

As we landed, there was one final ritual to perform, one I nearly forgot.

“It’s Song Wei,” she said.

“Sorry?”

“My name. All this time and we never asked each other for our names.”

Of course, something as wonderful as a song, as music, defined her name.

“Mine is Carlo.”

The lights rushed on. Passengers quivered from the sudden transformation of noise and energy, the attendants raced down the aisles, they reminded us of the rules, and we prepared for landing. An orchestral track played over the speakers. Slow, it nonetheless had a familiar quality. Bernard Herrmann? They had to be joking. The score belonged to Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Its eerie sound continued after we hit the tarmac and as we exited the plane.

*

Taking care of Alfonso’s relatives, hearing them talk, and listening to plans for the funeral throughout the day took a lot out of me. That first day, I fell asleep early and easily when I returned to the hotel. By my third day back in Guadalajara, I had adjusted to the time difference and managed to stay awake long enough to enjoy a drink at the hotel bar. I sat across from the bartender, whose long and curly hair bounced as she prepared drinks. After finishing my cocktail and paying my tab, I crossed the lobby to the elevator, and suddenly there was Song, her arm wrapped around a man’s. Dressed in light linen, he looked local enough, while Song Wei wore a blue floral summer dress. We locked eyes, and she waved without an interruption. She hoped to see me later. At least that’s how I interpreted it.

“Excuse me.” I returned to the bartender. “There’s a Japanese woman by the name of Song Wei staying here. If she asks or if she sits at the bar, could you hand this to her?” The bartender nodded, her curly hair falling into her eyes.

I left a note with my name and a suggestion that Song have the concierge call my room. Including the room number felt too intimate, implicating myself as interested in only one thing.

Upstairs, in bed, I mentally reviewed the look the man on Song’s arm had given me. In between these thoughts, I wondered if the bartender would know Song from all the guests in the hotel and if the note would ever be delivered. To my surprise, an answer came at four in the morning. The hotel’s telephone rang. I put the receiver clunkily against my ear.

“Carlo?” Song asked.

“It’s me,” I said through a mistimed yawn. “I saw you earlier and thought if you’d ever like to talk—”

“—Yes,” she interrupted. “I’m in the hotel bar now.”

“Now?”

“Yes, it’s not open, but I have a story to tell you.”

I must have yawned—an instinct from the hour—because she began to sound a bit more urgent.

“Please, Carlo, I do think I can trust you on this matter.”

Two in the morning, seven in the evening, or three in the afternoon. I would have come to her no matter the hour.

*

Down the elevator, through the lobby, and toward the bar, I passed the bartender who was mopping the floor. She smiled, but I missed her eyes because her hair fell over them again. I turned the corner.

Without people, the bar was anything but a marvel. Brown chairs surrounded three empty glass tables. Earlier, these were occupied by working businessmen and their laptops. The bar itself was a wooden platform with a golden top and a long mirror behind the bottles. Seven barstools fit along it. All but two were flipped up, and Song Wei was sitting on one. Her dress had a quarter-open back. Long, black hair obscured much of her bare skin. If others could see us, it wasn’t hard to fathom Their impressions: questions or snickers about the older woman and a man half her age gathering so late in a closed hotel bar.

Amber light from dusty overhead bulbs filtered the whole bar into filmic twilight. It had the effect of rendering her body as the one piece holding all of reality together. She leaned forward, and in the mirror, I could see her hands resting on the bar, one over one another, her eyes darting forward.

A few seconds passed before I said hello. She turned, and though she had invited me down, and though she should have noticed me in the mirror, she acted a bit startled. The following smile seemed an afterthought.

Her hands did not come apart, and as I came closer to take the seat beside her, I realized it was because her palms held the thin ends of a transparent plastic bag together. Water in the bag came up to half the length of her arm, and in it was a pink axolotl. The salamander looked away from both of us.

“I’m glad to have found you, Carlo,” she said. “I don’t know if I can trust anyone else. It’s not like I have friends or family here.”

I could have snapped back: What about the man? Two of you looked cozy enough.

I stayed quiet.

“I went to visit my son’s living quarters when we landed. Talked to his landlord. Talked to nearby neighbors. Talked to them all in a terrible Spanish that should have me arrested. He was such a quiet and professional man that they didn’t have much to say about his life, personality, or hobbies. All his friends were local cooks at nearby restaurants, and that is where he spent most of his time. I thanked the neighbors and was let inside. A spartan, my son did not seem to give dust a fighting chance. Not that it was hard, the way he lived. Books about food and notebooks filled with recipes were the only real sign a person lived there.”

The axolotl in the bag started moving. Small arms pushed against the bag’s bottom. With a large and wide yawn, it reminded me of the hour.

“I pored through the notes and the writing. My son possessed a variety of talents. Penmanship was not one. Recipes and ideas for dishes require an academic to translate his handwriting. I’m not one. All I have brought back are the legible notes.”

She pointed her nose down. The encouragement led me to notice a small dark purse on her lap. Not wanting to release her grip, she used her nose again to direct me to open it.

“Please, look at the first recipes,” she said.

I opened the purse. Doing so felt intimate. It was filled with banal clutter—makeup, tissues, and tampons—and I had to dig to pull out the papers. Two condoms almost fell out of the bag as I did so. Those did surprise me, and I wondered if she intentionally brought them to Mexico despite the trip’s despondent purpose, or if she always carried those around. I remembered the man on her arm from earlier and shivered to burst the bubbles forming in my loose imagination.

At last, I found the index cards and loose sheets. Most of the recipes described or listed the ingredients of common cuisines. Mole. Aguachile. Cochinita pibil. None of these were so unusual as to require physical study. As local and delicious as they were, these were familiar dishes—a mere Google search away for anyone interested in the nation’s culture. But then I stumbled on the second to last recipe. The poor script would render any interpretation uncertain, and it was difficult to make out what the writer described. All I could decipher was one word: axolotl.

The axolotl in the bag seemed to read my mind. When I looked up, both the amphibian and Song were staring at me.

“I have to ask you a favor,” Song started. A real sense of urgency stole her voice, as if my decision could save or defeat her life. “I found this axolotl in my son’s room. Please watch over it. You saw the card listing it as an ingredient. I must know what my son wanted to make, what he wanted to use it for. It’s the last way to understand him. And, already, there are others who want to know too.”

Song released her hands, and unless I wanted the water and Axolotl to splash to the floor, I had to reach out. With my right hand, I did just that, and caught the top of the bag as the water threatened to spill. My palm became wet. The axolotl swam back to the bottom.

“Thank you,” Song said. She placed both her hands over my left one, looked me in the eye, and said it again. “Thank you.”

*

Retreating to the room with the bag in hand invited stares from the few night-shift workers. Kind smiles and professional grins from earlier disappeared into accusatory scowls. What could I be doing with such an endangered animal?

Online, I researched how to care for the axolotl. I filled the bath a quarter high and placed the creature inside. I stood there and wondered what I’d gotten myself into. Song promised she would see me tomorrow night, when she had dug around her son’s house a bit more, and when she could confess more about her findings. But what did I know? Even now, I had not learned her son’s name, who that man was, or why she felt the need to turn the axolotl over to me. Not that I was in the practice of asking questions at the right opportunity. Wouldn’t most men have pushed back against a stranger—even one like Song—thrusting a responsibility on them? Wouldn’t most have wondered why a chef from Japan felt the need to cook the poor, endangered amphibian?

Back in the U.S., the axolotl is largely banned. The level of damage they pose to environments outside their own is catastrophic. I did not know if these warnings or legal boundaries applied to Japan. If so, was it the danger or exotic quality of the axolotl that drew in Song and her son?

There were other matters to attend to. In the morning, Alfonso’s mom wanted me to speak with a florist, and a caterer, and a priest to settle the ins and outs of payment. The outsider, she thought, might best negotiate the price. Terrible logic. All she wanted was me to pay. Alfonso, you bastard, if you weren’t my favorite cousin—

The hotel telephone rang. I wondered if Song forgot to mention something, or if she would maybe want to come here. But it wasn’t her. I picked up and sat at the far edge of the bed.

“You’re wrong if you think her son wanted to eat him.”

A woman’s voice? Strong and stern, it wasn’t familiar. The caller continued:

“Her son liked to cook and loved to study recipes, but he wouldn’t eat the axolotl, not after getting to know the little guy. He had common sense.”

From where I sat, I could peek into the bathroom. Over the tub’s edge was the axolotl’s tiny head and pink hand-like claws helping it to hang on. It appeared to eavesdrop.

The caller continued. “Did you know axolotls were named after a god capable of breathing fire and lightning and regenerating its body? Believe it or not, an axolotl can still do two of those things.”

“I believe you.”

“You don’t sound so impressed.”

“I’m more curious how you know so much. How you know I have the axolotl? How you know about Song’s son?”

I rummaged through my luggage on the beside floor. The Death of Ivan Ilyich lay on top of my clothes. The book was the basis for Ikiru. Earlier, I planned to tell Alfonso I read it while in Japan.

“Do you know how important axolotls are in Mexico? You don’t carry one off without half the country speaking about it. People talk. People gossip. And some people? They’ll fight to save the axolotl. Or they’ll fight to kill it. Song’s son attracted all kinds of attention with what he wanted to do. That card in his collection? It is only partly a recipe.”

“What was he doing, then?”

“Attempting to recreate their habitat.”

“Did it work?”

“Not at all. But at least he tried. His home resembled something between an aquarium and a mad scientist’s lab. They have one native habitat left back in Mexico City. Hey, you heading to Mexico City any time soon?”

“Wasn’t planning on it.”

“Well, if you do, drop him off in Lake Xochimilco.”

“If you’re so interested in returning him to the lake, why trust me—a foreigner?”

“Because it’s your choice. She entrusted the axolotl to you. The lake is on its way out, you know. Too much pollution over the years. Because the axolotl can clean it up, and because there are so few things in life like the axolotl that can erase a history of human error.”

“To be honest, it’s not that I don’t trust you, it’s that I can’t quite see how one axolotl is so important. All Song wants is—”

“—Song. Song. Song. Get your sex-deprived mind out of the gutter and listen to me. Unless you want Lake Xochimilco to dry up and die, you can’t give the axolotl to anyone. It’s your choice whether you get him back to the lake. Until you decide his fate, don’t leave him alone at all. And don’t let Song eat him.”

*

The caller promised she would call each evening to ensure both the axolotl and I were safe. Part of me liked having a discussion to look forward to—even if I didn’t understand it all. Since Alfonso died, I hadn’t talked in-depth with someone.

Well, except for Song.

Because of this lack of practice, I forgave myself for having lost the habit of learning names. The caller came and went without one. I had almost done the same with Song on the plane until she offered it to me in an equal exchange.

But names are important. They are spells unto themselves. Take Lake Xochimilco. In the language of the Aztecs, the name refers to a flower field. (And no, I didn’t just know that. I had to look it up.) My point is that the name—Xochimilco—endures to tell us what was once there. Even if the land no longer looks like that, even if time and evil corrupt the earth and prevent flowers from growing, Xochimilco reminds us of what once was there.

That wasn’t all I found. Unable to fall asleep, I scanned stories about the place.

Lake Xochimilco is the last of a beautiful water network that survives a history prior to Spanish contact. Colorful boats float along the water and gardens grow along these vessels to sustain a forgotten and beautiful agriculture. Once a common sight, the number of boats has dwindled, and the tradition has declined with the lake. I watched a video on YouTube of a farmer who explained the lake was a living and breathing being, dying by coughing its last breaths. The water turned black and wondrous gardens burned up. What was left was all that was left…