BALIKBAYAN FILLED WITH THEORY by Dujie Tahat

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Ariel Francisco

DREAMING OF THE GOVERNOR AND THE MAYOR PLUNGING INTO THE RIVER

Perhaps conjoined at the ankle

by a concrete block, like the tails

of Pisces. Yes, let them embrace

the East River together in early

morning so they may be blessed

at last by the light of a new day

rising beautifully without them.

MY DAD’S BIRTHDAY IS WRONG ON HIS BIRTH CERTIFICATE BECAUSE HIS PARENTS COULDN’T AFFORD TO PAY FOR IT WHEN HE WAS BORN

Officially my dad was born

June 3rd, 1957— that’s what all

of his documents, signed and notarized

claim in both countries that claim him—

though unofficially, hearsay,

there’s no proof that he entered the world

on April 11th, 1957: photos can be

doctored and both parents dead,

only the scowl on his face when it’s

brought up can serve as testament

to those fifty-four unaccounted days.

There is being born into poverty

and then there is not being born

because of poverty. One must pay

to come into existence and my dad’s

existence was delayed two months

because his parents could not.

There is something unforgivable

about being denied time, about

being made to feel as though you need

to catch up to yourself, make up

what’s been lost— no, what’s been taken.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary

I do not like dwelling on the past,

especially one inherited so heavily

and without consent; but I can’t help

but think of how being a dollar short

seems to be a family trait, of how

my grandparents split, fell apart

like dead trees in a storm, of how

my dad grew up to meet my mom

and repeat that cycle, unintentionally,

but intentions don’t matter when you’re left

indebted to the wreckage—

of how things could have been different

of how things could have been different.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Melissa Crowe

SOBRIETY SONNET

with apologies to my brother, 11 months clean

The boy who cried sunlight, summer rain,

bird-in-the-bush, in the hand, who cried

fiddleheads, brook trout, berries in the field

by the chicken house, again and again

who cried lilacs, from each bloom

a hit of nectar and nothing to fear—

he’d pretended for so long the all clear

while something hungry paced the room

that even when of true wolflessness

he made a bouquet so pretty and perfumed

nobody in her right mind could presume

it wasn’t flowers, I called it beast,

saw in the gold-dusted mouth of each bud

a dogtooth sharp enough to draw blood.

EPITHALAMIUM WITH PAPER BELL

I was there on the day my mother married—

I’ve seen photographs of her in her borrowed

dress, bodice of a taller friend wrinkled

at her waist, slack satin pooling at her feet.

Her forehead shines above a startled smile,

and my sudden stepfather, in a rented tux

of powder blue, just looks glad. There I am,

too, tucked between them on my final day

of being five years old. I don’t remember

the ceremony or the reception, the kind I’d

later love when my mother’s younger brothers

wed their first or second wives at the Elks club

or the VFW, center of the room cleared

for a dance floor, tables pushed to the walls

and spread with crockpots of cabbage rolls,

spam salad spooned into hotdog buns.

Beer bottles and ashtrays. Uncles with their

sleeves rolled up, Red Wings buffed of mud.

When they weren’t twirling girlfriends

with spaghetti straps and long-long hair,

pulling them close for the slow tunes,

they lifted me into their arms so I could hug

their whiskered necks. There’d have been

a deejay and gallons of milk mixed with Kahlua,

a dollar dance, man after man paying to twirl

my mother a little, money for the honeymoon,

one night in a cabin at Portage Lake then back

to the shoe factory. But I only remember

the paper bell I found taped to a table that night,

miracle the way I could close its feathers so

easily, conceal the whole voluminous thing

between two half-bells of card, then open it

as swiftly as lungs can fill with breath.

Like hands that part to reveal what I’d

wished for bent at the bedside, what I’d seen

in my head and whispered into the dark.

I could almost have believed I heard it ringing,

that tissue bell, marvelous flat nothing

come to song. I kept it a long time, precious—

and then I guess I lost it. I guess we all did.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

COMMENCEMENT SPEECH, DELIVERED TO A HERD OF WALRUS CALVES by Matthew Olzmann

Young walruses, we all must adapt! For example,

some of your ancestors gouged the world

with four tusks, but you can grow only two.

It’s hard to say what evolution plans for your kind,

but if given a choice,

you should put in a request for thumbs.

Anyway, congratulations! You’re entering

a world that’s increasingly hostile and cruel

and full of people who’ll never take you seriously

though that will be a mistake on their end.

You are more tenacious than they know.

You’ll be a fierce and loyal defender

of those you love. You will fight polar bears

when they attack your friends and sometimes you’ll win.

Of course, odds always favor the polar bear,

but that’s not the point. The point is courage.

The point is bravery. The point is you are all fighters

even when the fight in which you find yourself

ensures unpleasant things will happen to you.

For example, the bear will gnaw apart your skull

or neck until you stop that persistent twitching;

it will eat your skin, all of it, then blubber, then muscle,

then the tears of your loved ones, in that order;

it will savor every bite, and you will just

suffer and suffer until the emptiness can wash over you.

The good news is: things change!

For example: the environment.

Climate change, indeed, is bad for you,

but it’s worse for polar bears whose conservation status

is now listed as “vulnerable” which is one step removed

from “endangered” which is one step removed

from “extinct” which is a synonym

for Hooray! None of you get eaten!

I suppose this will make some people sad.

Even now, they’re posting pictures

of disconsolate polar bears on melting ice floes

drifting toward a well-deserved oblivion.

They say, We need to stop this!

They say, We need to do something, now!

These people are not your friends.

One cannot be on both Team Walrus and Team Polar Bear

at the same time. I’m not saying these people are evil;

I’m saying, it’s time to choose a side.

I’m saying sharpen your tusks, young calves;

your enemies are devious. You need to train

yourself to do what they won’t expect.

For example: use computers, invest

in renewable energies, read Zbigniew Herbert.

Unrelatedly: your whiskers make you appear

to have mustaches, which, seeing as you’re

not even toddlers, is remarkably unsettling.

Babies that look like grown men freak me out.

Like those medieval paintings by so-called masters

where they’d make the face of little baby Jesus

look like an ancient constipated banker.

If that’s what God really looks like,

it’s no wonder we’ve done what we’ve done to the Earth.

Maybe you can repair what we spent lifetimes taking apart.

Replace some screws. Oil some hinges.

This might sound impossible, but have you ever

looked at yourselves? Seriously—take a quick look

and tell me how a walrus face is possible;

everything about it defies the laws of physics.

You will exist beyond the reach of nature.

You will learn to slow your own heartbeat to preserve oxygen

while diving to depths of over 900 feet.

You will stay awake for up to three consecutive days

while swimming on the open sea.

And when the ocean is too rough—

so terrible with longing, so ruptured with heartache—

you’ll find a small island of stone or ice offering refuge.

It will be difficult to climb from the water,

but because there’s hope for us all,

you will hoist yourself up,

using only your front teeth to drag your body

onto the shore.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

MONSIEUR REYNARD by Holly M. Wendt

Renaud com richchande thurgh a roghe greve

And alle the rabel in a res, ryght at his heles.

— “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” by anonymous

but what is the fox to think, duck-tumbling through green with all the dogs baying at his heels, of the scene unfolding across a hill inside stone walls much higher than the fences the fox can leap, inside the curtains and sheets sweetened with lavender, sweetened with words and hands touching: a man and a woman and the frightful truth that what you give is what you get but only if you’re one of the people in the story, only if that’s how you’re seen. a fox isn’t a person, a fox isn’t given, a fox has to get all on its own: a rabbit, a den, a mouthful of feathers because hunger is a gag in the throat, an acid turn in the belly; hunger is wanting and wanting and when someone does give a fox, it is not the soft part of a bird, not the thing the fox wants but some lines in a poem: a fox is gotten, a fox is given to someone else but only after the fox is dead and only to remind the man in the bed of the wager he made against the fishbone sliver of his life, and no one kisses the fox three times because a fox doesn’t know about kisses—

but a fox knows about fucking, a fox knows about a pull, a pull, an arch and bite and everyone in the fox’s poem knows about that, too—

but the fox isn’t a person no matter the name that’s offered; what good are names if the ink’s half-flayed and no one is who they’re supposed to be, not even the knight? were it otherwise, a fox might turn and fight, a fox might have some kind of agreement, like the man in the bed with another man’s wife (though they’re not fucking, only kissing and that only a little too), but this is not that version. the man in the bed is going to give those kisses right back to the man who is chasing the fox and trying to give a gift of a redbrush tail that no longer hides gold eyes, that no longer follows four fast feet, and it would be a handsome gift—all this soft amber of running, living, warming—but it’s not a gift, it’s a threat, like the horses chasing the fox, too, there behind the dogs, and the fox has tasted horse once. the fox found a dead one and all over its sleek hide the smudge of men and metal, but the bones broke easily enough and the sun-sour meat tasted like life and monsieur reynard doesn’t know what a promise between men has to do with foxes—just the same as a boar doesn’t know, just the same as the hart, both already hunted, both already still and spitted, and no one has to know, do they, to end up dead for it, to end up caught, to end up peeled bare, to end up in someone else’s mouth? and the fox doesn’t know this isn’t to do with food or fur because for the fox it is, and for the man in the bed it’s about keeping clean, which is also about keeping uncaught, keeping unbloodied, and for the woman taking his hand, it’s about finding out where the nail catches the skin and can peel it back—how much comes free in one piece? and for the man on the horse (all these men on all these horses) it’s a game to be played. the man on the horse lost his head to the game and picked it up and walked away, and a fox doesn’t know such a thing is possible because such a thing is not possible in this poem—at least for foxes in this poem—which is old, old, old enough that the pigments have scraped themselves thin. all the blood and the robes that were once real stones, once real things—

it’s the green that lasts least, all this green so lush and growing and false, though there is nothing truer than some shoot’s first twining and nothing truer than the ease of it crushing underfoot; it is not the province of a fox to follow these stems and roots. a fox follows low cuts between leaf and branch and the twisting trails toward warmth and blood. a fox only runs and pants against the pack’s closing howl and lunge—

inside the room the lady has a gift to save a man’s life if only he accepts and he’ll accept because if he doesn’t—

no one brings such a gift to a fox, to a body so desperate, no one brings water for the tongue dry and lolling, no one brings a soft green cloth to dab away fear’s white foam and bind up the soft underbelly, and no one asks as the strength fails in one limb and another and no one opens a door, breaks a fence, moves a stone—but what bargain wouldn’t this fox make right now right now, what wouldn’t he exchange—

what wouldn’t the boar, what wouldn’t the doe, what wouldn’t anyone trade to keep feeling the drum under the feet, that feeling of beating alive alive just the same as the heart?

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

ALL WE HAD TO DO WAS SWIM by Jon Bohr Heinen

I ducked down a side street when I saw the red and blue lights coming from the police cruisers blocking the Burnside Bridge. My big brother, Joel, trailed after me and asked, What’re you doing? I told him I’d never seen so many cops before; the only policeman I’d encountered was the one who visited our middle school to talk about the dangers of illegal drugs. They aren’t interested in us, Joel said. He took me by the wrist, led me out of the alley, and told me, We just have to make it past them to the river. Then all we have to do is swim.

The streets were wet and slick from rain and reflected the light of the moon. Ahead of us, the Burnside Bridge was drawn, halting passage across the Willamette River to the west side of the city. Officers milled around the cruisers, assault rifles slung over their shoulders, sipping from Styrofoam cups. We were close enough to hear the chirp of the walkie-talkies. A crackled voice said, Please be advised. An officer responded, Ten-four.

*

It all started a couple months earlier, with a single pothole on Ankeny Avenue. Then there was one on Morrison Street and another in Old Town. Every weekend, our dad picked us up and we crossed the river to stay at his apartment in the west side of the city, and each time we went there—whether we were going to the nickel arcade or on our way to browse books at Powell’s—we spotted more cavities in the streets.

Joel said, Every week it’s worse. But nobody made a big deal about it. In an interview on the evening news, a city council member said, This is just the routine erosion of infrastructure.

Crews were dispatched to make repairs. They came in white-paneled trucks and shoveled fresh asphalt, but for each pothole they patched, more appeared.

The last time we were with our dad, we got frozen yogurt from This Is Culture. We were walking up the street, cones in hand, when a Loomis Fargo truck hummed by. I doubt we’d even remember that truck if it weren’t for what happened next. One of its wheels sank. The truck slumped and came to a stop. The driver punched the gas, and the wheel spun, climbing just a little before the asphalt crumbled and the wheel slid back into the rut. The driver hit the gas again. The engine whined. Black smoke rose, stinking of burned rubber. The tire blew and the naked wheel dropped into the pothole. Then the ground gave way and the front half of the armored truck sank into a growing opening in the street. The driver clambered out the rear door and fled to solid ground.

Let’s get you home to your mom, our dad said.

We crossed the bridge back to the east side of the city. As soon as we walked into the house, we told our mom what had happened. She said she knew we were worried, and that Dad could stay with us for a while if he wanted. In that moment, I imagined all of us back together, like whatever had come between them could be forgiven and forgotten, but our dad shook his head. He assured us the whole thing was just a freak accident. It’ll be okay, he said.

*

We’d never heard of the Shanghai Tunnels, but once the Loomis Fargo trunk sank into the street, they were on the news all the time. Reporters opened trapdoors and pried open manholes. Beneath the west side of the city was a vast maze, pathways that led to openings along the Willamette River.

Some thought that the tunnels were just an outdated means of transporting goods to and from docked ships, but rumor had it that young men had once been dragged through the tunnels and sold as slaves to ships bound for Shanghai. Whatever the tunnels had been used for didn’t matter much now. The streets were sinking into them either way.

Even so, people carried on as if what was happening wasn’t happening. The city tried to reinforce the tunnels with lumber buttresses, but the streets just crumbled around them, leaving standing ribs of wood and asphalt. They tried to pump concrete into the tunnels, but the trucks were too heavy to drive around the west side. They parked on the Burnside Bridge, long tubes leading out of the mixers, burping cement. Then Big Pink, the tallest building in the city, fell. Forty-two floors worth of shattered glass and twisted metal collapsed into the tunnels, countless bodies buried in the wreckage. The city placed an evacuation order, but not everyone made it to safety before more buildings came down: the Overton Towers, the Wilkins-Spaniel Center, and the Harrison Tower Apartments, where on weekends we lived with our dad.

*

Our mother couldn’t turn away from the TV after that. He should’ve stayed, she said, speaking to footage of the wreckage on the screen. Joel told her, He might be okay, but our mother shook her head. We hadn’t heard from him in days, but I wanted to believe what Joel believed: that our dad was still beneath the rubble waiting to be rescued.

*

He was right about the police; they didn’t even notice us walk past when we made our way to the river. We knelt by the bank and dipped our hands into the water. I said, It’s cold. Joel told me, We’ll get used to it. Then we waded into the river together.

We were only waist deep when the current swept us away from each other. I struggled to swim, but I was quickly pulled under, stuck in the current, suspended between the river bottom and the air above it. It was like flying, though I couldn’t breathe. I saw nothing but darkness punctuated with pops of light. I was sure I would drown, and right as my lungs went empty and my throat filled with water, I felt a tug around my neck.

When I resurfaced, Joel had me by the collar and was pulling me back ashore. You’re okay, he said. You’re okay, you’re okay. He got me out of the water and onto the bank. We were far downriver from where we’d started, the police lights no longer in sight. I coughed up the water I’d swallowed and began to sob. Our dad was beneath the debris on the west side, dying or already dead. I wanted to believe there was something we could do, but we couldn’t save him. We’d barely been able to save ourselves.

Joel put his arm around me and said, Don’t cry. Then we sat there, cold and wet on the bank of the river, and watched the city buckle in the distance.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

EXCERPT FROM THE HISTORY OF LITERACY by K-Ming Chang

Smaller Uncle claimed he could predict a flood was coming when all his nose-hairs swooned and sprinkled the sink. A long time ago, before he washed cars, he used to be a weatherman, which I thought meant he could manufacture weather, plucking out strands of his own hair to double as lightning, the way the Monkey King scattered stalks of his hair to multiply himself, but Medium Aunt told me that actually, it just meant he used to stand in front of a cardboard cut-out sun and guess what time the sky would arrive. My uncle got fired for making a lot of shit up, she explained, like one time predicting a rain of crab claws, and of course everyone was very upset about that because crab claws are delicious and they were all waiting for that day with their pots full of boiling water to catch them. Smaller Uncle interrupted and said, I didn’t mean it would rain literal crab claws, I said that the raindrops would be as large as crab claws, and they’d latch onto you and twist out the meat of your palms, and besides, in the end it didn’t even rain any size and everyone blamed me. That’s nothing, Medium Aunt said, the real scam he pulled is that he can’t even read. The channel was local and there wasn’t a teleprompter or anything, just this guy smoking and holding up pieces of cardboard with the script on it, and your uncle would just make up the script, saying shit like, Tomorrow is sunny with a chance of getting stabbed, likely there will be a night, and all this week there will be sporadic skies soiling themselves. It will be cooler under the shade, so grow some trees. It won’t rain unless you have a leak.

In the sofa bed I shared with my Smaller Uncle and Medium Aunt, I was pocketed between them like a switchblade. In bed, Smaller Uncle laughed so hard at his own made-up weather predictions that the whole apartment rattled like a broken jaw. We fell to the ground, and Uncle rolled me under the sofa bed and said, I forecast it is now earthquaking. Seek shelter beneath your nearest niece. His laughter could even dislocate the building like a shoulder, shifting it half a block up the street, and no one could predict it. Sometimes he would just look at our walls and laugh, and when I asked him what he was laughing at, he said he was reading the mold. It’s making fun of me, he said. There was mold on the wall in the shape of a mouth, and he claimed he could read its lips, claimed he could order the ants on our ceiling to arrange a single sentence. Okay, then what are they saying, I asked. They’re saying you should stop smashing us into sesame paste with your fingers and let us be fluent in foraging, he said. Fine, tell them I don’t like them crawling into my mouth when I’m asleep, I said back. Smaller Uncle shut his eyes, sketched lines in the air with a single finger. Okay, he said, I wrote back to them, but just know that they enter your mouth at night so that you’ll have words to speak in the morning. You think we make words ourselves? We borrow their bodies to speak. That’s nice of them, I said, but still taped my own mouth shut at night, laying strips of tape sticky-side-up around the bed. I asked Medium Aunt if she thought tonight would rain, and she said, I hope not, our ceiling doesn’t even hold up against the dark, look how tomorrow’s leaked in. The mold will multiply into men and then where will we go, she said.

That night, Smaller Uncle told me more stories about the extreme weather incidents he lied about, how he invented local locust plagues, volcanic eruptions, and the impending extinction of the sea. He claimed the sun was a severed head. He said the people of Rudong County believed him so thoroughly that they removed their roofs the day he predicted a hail of pearls. Stop laughing, I told him, I don’t want the city to get a splinter tonight. Okay, he said, and told me another story. About a man named Cangjie who had four eyes. All four were the size of pearl onions in a cocktail of light. This was a long time ago, he said, back when the moon was square, before they realized that light with corners caused accidental eye-gouging when you looked at the moon. One night, the emperor told Cangjie that all across the kingdom, people were rioting against knots. Knots were the only form of writing, and it was beginning to progress into weaponry. Nooses and handcuffs and hogties. So the emperor begged Cangjie to find an alternative. The alternative to a knot is a knife, I said, and the emperor sounds like an idiot. Smaller Uncle smiled and said, I’ll have to decapitate you for disrespect. Listen. Cangjie sat beside a river, but all day it spoke nothing to him. He sat in the mud, but it had no tongue, only stones that settled into the crack of his ass. I told Smaller Uncle that this story was slow, and he said, wait for me to make up the weather. Up in the sky, a crow flew by and dropped a hoofbone at Cangjie’s feet, but he couldn’t read what species the print belonged to. He consulted hunters all over the kingdom, and one finally told him that it was the hoofprint of a pixiu, a species that stomachs gold. Cangjie copied its shape on the sole of his foot and stepped onto a scroll. And that, Smaller Uncle said, was the first written word. I told him the story had holes, like who was the hunter, and why was the bird holding the severed hoof of a pixiu, how did it know where to drop it, and where was the pixiu going, and what did gold have to do with rivermud. He was silent, looking at the ceiling again, and I wondered what he read in those cracks that chronicled our lives, those ruts filled with our blood. You see, he said, a word is just the shape something makes when it falls. Rain too. I imagined the transcription of my feet in mud, how deep a word I would be.

Open your mouth, he said, listen to the leaks saying there’s rain coming. He opened his mouth, and inside I saw the larvae of a language, clung to the roof of him, clusters of light inside. I opened my mouth too, stretching it wide, and waited all night with him. But there was no rain, and in the morning, when I turned my head toward my uncle, he was asleep with his mouth already shut. Medium Aunt was awake in the kitchen, backlit by the TV screen. I kept my mouth open until Smaller Uncle rolled over and told me I could close it finally, that he was wrong after all. In the kitchen, we sat cross-legged on the floor and watched our dumpster-dive TV, which could no longer speak after Smaller Uncle accidentally kicked it over one night when he was drunk. It also meant that some of the faces went missing, and so we identified actors by their shoulders or shadows. After the sound surrendered, Medium Aunt kept the subtitles permanently turned on, and we took turns reading them aloud. Smaller Uncle was silent when we did this, turning his head to the wall, so we pretended to read them aloud just for ourselves, saying the lines like we were repeating them out of shock, like wow, that can’t be true, that there was traffic today, that the clouds came by wind, that the concubine was going to bury the other concubine’s baby alive, that the drought would last for another two hundred years at least, that a fire was furring the sky, that a new species of fish had been found and it used four pairs of eyes, and Smaller Uncle lowered his head and pretended not to listen, sitting cross-legged on the sheets of newspaper we spread on the floor before every meal, the headlines rubbed blank by our knees. He stared at the moldy wall, even after we turned off the TV, sitting still for the ants collaring his neck and stampeding down his spine. I opened my mouth to recite the newspaper headlines swarming around his legs, but he shushed me and said he could do it himself. He told me that all he had to do was sit like Cangjie did, waiting for something to fall, to mean something in the mud. All you have to do is look long enough at something you wanna say aloud, such as the sky, he said. Tomorrow I’ll write you into it.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

Radical Imagination, or Empathy: An Interview with Eric Tran

The Gutter Spread Guide to Prayer is the debut of Eric Tran, released through Autumn House Press in Spring 2020 and selected by Stacey Waite as the winner of the 2019 Autumn House Rising Writer Prize. He previously published the chapbooks Affairs with Men in Suits (Backbone Press, 2014) and Revisions (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2018). Eric Tran is a writer and physician, based in North Carolina.

FWR: How are you doing?

Eric Tran: I’m doing well. I just got off this really intense rotation and this is the first weekend where I don’t have to go back on Monday. It feels like a nice chance to get back into the world. How are you?

FWR: I’m doing alright. It’s week two of school, so it’s back at it.

ET: Are you online or in person?

FWR: We’re in person. I have a few students who are remote, but the majority are in person. My students are wearing masks and they’re trying to stay apart, but our school is not sized so that they can always stay apart appropriately. It feels like a waiting game, unfortunately.

ET: It’s a valiant effort, and hopefully people stay safe. Hopefully, it’s not that people get hurt and that’s why things have to change.

FWR: Yes, I think, and I’m sure you see this too, that folks want to do the right thing but there is this disconnect between wanting to do the right thing and not wanting their lives to change.

ET: Yes, I feel like there is this lack of radical imagination, otherwise known as empathy, of being willing to sacrifice what you have. It’s very unfortunate that the only way for some people to be able to recognize that tragedy can befall them is when it happens to them.

FWR: Exactly. It’s an inability to imagine a broader context. Which, I guess, brings me to the way The Gutter Spread Guide to Prayer obviously plays with characters, plots and themes from various comic books, but I’m interested to talk about to what extent the structure and style of comic books influenced the writing of your poetry. Did you feel the structure of a comic page influencing the way you visualized poems’ layouts or their syntax?

ET: I think that we forget that poems are visual objects, in addition to being text to be read, which I think gives another layer of richness. I prefer to write in white space. I think a line by itself is just a little too lonely, it’s a little too much to be putting on that single line. So I prefer couplets or tercets, lines that have more space around them.

Speaking of the coronavirus, I’ve been thinking a lot about breath in general. I’ve been working on this essay about breath, how necessary it is but also how we take it for granted. We assume that it will always be there, that it can always be there when we need it. For example, if we’re reading a prose block and we need air, we can look away from the page, but what happens when the text requires us to stay with it? If there is something so important that we must stay with it, can we give the reader some air within it? Does taking a breath necessarily mean stepping away from it? I think adding white space to your poems or your prose is a way to strike a compromise. I think that exists within comics as well.

I’ve been reading a lot of Tom King, and he is really drawn to this idea of six panels per page, which can be fairly rigid or overwhelming. But because he has the gutter, the space between panels or the margin, this margin allows us to take space between each panel where you can linger for as long as you need. I think the white space on the page of a comic book does a lot of things that the white space in poetry does; for example, moving from one panel to the next, sometimes it’s linearly connected (such as in one scene someone is sitting on a couch and in the next scene they’re standing up), but something will have happened between those two panels that we didn’t see. The white space signals that a jump is going to happen, and it clues the reader to take a breath and take the jump with the narrator. Or, sometimes if it’s a more experimental comic book, something even bigger can shift in that white space. Tom King, or rather the layout artist, decides how big that white space gets to be; sometimes it’s very minimal and sometimes it’s very large. I think comic books are playing with that narrative leap, much like poets like to. And that’s if we’re just talking about comic books that adopt that layout with panels and gutters. Some comics will have someone leaping across that white space or a hand reaching from one panel to another, which I think is very daring. Similar to poetry, that space is not just a place to take a breath but it’s also a place to do work in, to transform the poem or the layout.

FWR: What you’re saying about taking these leaps makes me think of the trust the writer must have in their audience and the material that they are generating.

ET: Most certainly, and a willingness that the reader must have that they are in good hands. I think that adhering to a kind of form, even if you end up breaking it, or it’s a loose or challenging form, gives that trust in the confidence in the artist and a structure to lean on. We all need to structure, even if we demand freedom; it must be freedom from something.

I think that adhering to a kind of form, even if you end up breaking it, or it’s a loose or challenging form, gives that trust in the confidence in the artist and a structure to lean on. We all need to structure, even if we demand freedom; it must be freedom from something.

FWR: Thinking of how you lean towards couplets or tercets, how did you find your way into the prose poems that are in the manuscript?

ET: I started my MFA as a nonfiction writer, but it turns out all my friends are poets, so I got pulled in. To be quite honest, I think that prose is always poetry. I was toying with sentences over and over, trying to make them beautiful, and it hit me one day that maybe I should make my words beautiful, as opposed to trying to build a narrative. A gateway from prose writing to poetry can be the prose poem. In this book, I think the prose poems make sense; I tend to be a poet who has a lot of narrative lines in his poems. I have been moving more towards more associative ways of using logic, but I do tend towards narratives. I think that one way to present it is in a prose block, because that’s how we tend to think of stories. And then I think that within that prose block, we can make leaps from one idea to another because there is a tight structure on which to rely. Then within those borders, you can be as experimental as you would like to be. In a way, this mirrors a comic book panel, which is usually rectangular and bound by a back and front cover.

In the book, I make a lot of leaps, such as from the Pulse mass shooting to the X Men comic books, which, in some ways, is not a hard association to make, but in other ways it is a hard association to make, moving from a comic book and kids’ TV show and multimillion dollar franchise to something very visceral, very real, and impacts people who are not multi-millionaires, who are not mainstream. I think the structure of the prose poem block contains those two more tightly than if you gave the distance of white space from each other; entropy might tear them apart. If you give them structure, they adhere more tightly.

FWR: Yes, exactly. I think there is so much juxtaposition in the text; I grew up in a Pentecostal house and the language that jumps to mind is being “of the world, not of the world”, or here, of the body and the body in these different places, whether it’s the body in the comic book or in an action film. I think of the way you move from high ekphrastic poetry to a poem that considers the guitar player in Mad Max: Fury Road (“Self Portrait as the Fire”) or Chris Evans (“Portrait as Captain America Holding a Helicopter with a Bicep Curl”), and then bringing it back to the body of someone helping a drag queen descend the stairs; the way that you’re moving in and out of these different worlds allows the various visualizations of the body to come together in a really cool way.

ET: I purposely try, as I said in my MFA thesis, to mix the high and the low. In some ways it feels very purposeful and effortful, and in some ways it feels very natural. We think of Keith Haring, who we think of currently as high art, or Frank O’Hara, who died on Fire Island, which was known for gay revelry, so these contradictions already exist together. And although those things exist together, I think hegemony, or the white washing of things, wants to push them apart. What our job is as artists is to reveal the truths that are already there.

hegemony, or the white washing of things, wants to push them apart. What our job is as artists is to reveal the truths that are already there.

FWR: I think that goes back to what you said when we first started talking about radical imagination and having that empathy to imagine a better world, or a world that responds to everyone in it. Did you feel like that in choosing or attempting to seek out truth, that that impacted your diction or the images you chose, in order to create a more expansive or more nuanced view of the world? I’m thinking of a poem like “Treatise On Whether to Write the Mango”, both for how the shifts in language mirror the shifting identities throughout the text, but also how you deploy interruption in the poem: “your ever-shitty teenager/ attitude (American!), never clearer/ when I woke wanting mangos/ instead of the rubbery jackfruit/ she woke at dawn to peel/ away from the thin white casing and so/ of course mangos”.

ET: I love the idea of radical imagination. I was part of this social justice, podcast listening group, and the podcast we were listening to was about how the principles of America were always set up to be against Black people. So we must radically imagine a new world, because the rules by which we play are inherently always going to resist change. Speaking of entropy, things always revert back to what they were.

So, using that radical imagination to imagine a world where everyone has a place within it, why then do we have to adhere to the diction, the imagery, the logic that existed in these previous worlds? I think poetry already does this. It supposes that there are other ways to make sense of the world, outside of the linear joining of two words to make meaning. If we accept that power, we can use whatever diction, syntax, imagery we want to hear. For example, there are times when I juxtapose the word “twink” with the word “prayer”. In a radically imagined world, I would love for twinks to be alongside prayer, and in my world, they are.

It supposes that there are other ways to make sense of the world, outside of the linear joining of two words to make meaning. If we accept that power, we can use whatever diction, syntax, imagery we want to hear.

FWR: It also creates humor too. In thinking about your work, and describing it to folks, you’re so clearly wrestling with grief, but there is also humor. With humor comes that sense of life. It doesn’t have to be a monopoly on one feeling.

ET: Yes, that speaks to this balance of extremes. Something I’ve been thinking about a lot is in mental health, we work with the idea of the dialectic, which are two disparate truths that seem to contract each other, but they come together to form a deeper truth. For example, a bowl is something that has had something removed from it. So, you have the something and the lack of something, and together they form this new truth, which is a bowl. So thinking about grief and joy, sex and death, not necessarily to find a balance between them, but instead attempting to establish a dialectic in which they’re speaking to each other. That’s something I love about the cover of this book; it’s neon, in your face, very gay, but it belies that there is a lot of tragedy within in. I don’t think that’s hiding anything. The first poem (“Starting with a Line by Joyce Byers”) helps lay out pretty clearly what the book is going to be about.

FWR: That jumps me to the Lectio Divina series, which meditates on characters ranging from Emma Frost to Hektor the Assassin, and the way that by holding those disparate parts together, the reader sees the threads that exist across different characters but also different experiences. To me, these worked as stepping stones to take the reader through the text. How did the Lectio Divina series of poems originate?

ET: The concept of Lectio Divina is from the monastic Christian tradition of approaching a sacred text in different ways. I was introduced to it through a podcast called Harry Potter and the Sacred Text, which is run by two folks who have Masters of Divinity. They approach the chapters of Harry Potter as if each has something to teach them, if they approach it earnestly enough. I started listening after Trump was elected in 2016; I stayed with it because, I believe in the first episode, one host said to the other ‘thank you for teaching me how to love again’. I felt like this was something we needed to relearn how to do. It is a funny, tongue-in-cheek show, but it is deeply serious as well. I also love the idea that they taught me prayer, because it feels like justice.

I think queer people, in particular, often feel excluded from spiritual practices, either because they feel excluded from many denominations or they feel like that need to decide between their queerness or their spiritual life, rather than having a dialectic or harmony of the two together. So, having a spiritual practice is a way of reintroducing a process by which to experience the world. During that time, I was also looking for a spiritual practice because there was a lot of loss in my life and I was thinking about how we learn to grieve. It’s not taught, formally or informally, and yet it’s one of the most important things we must learn how to do. I think spirituality can teach you how to do that, but if we exclude an entire group of people, who inherently have a lot of grief in their life, that is an injustice. So, using something like Lectio Divina feels like, to me, an act of justice to reclaim those spaces and bring them to my people.

FWR: This is making me think of how in so many spiritual traditions, there is also the sacredness of the body, and in your work, you have such attention to the body in your work, as if viewing it as a sacred text, a thing to be treasured, even if it doesn’t exist in the structures deemed appropriate or acceptable.

ET: I think most certainly the body is a text to be approached, spiritually so. To me, prayer is the act of paying attention to something you’re working with. We can approach everything as if it is prayer, but if we don’t know we have the ability to do that, we’re not going to do that. I think that prayer helps us deepen our relationship to things. I think this is the reason prayer is a factor in mental health– not religion, but spirituality in particular is a strong protective factor. So if we’re then aware of all the times in which we can practice prayer, that can only lead to a better life. I think so many things can be approached with prayer, which is part of what draws me to these so-called low texts, like comic books, which are not low texts at all, but would not otherwise be brought up in traditional religious circumstances. If we’re modeling the ability to do prayer in those circumstances and in very traditional circumstances, we’re showing ourselves and each other that prayer exists in all the spaces between. The body is one of those places, because the body exists in the high and low places as well. One way to think about approaching the body is to be with it, in sex, for example, or death, or loss, and think about how that special attention can guide us to and guide us through moments of wonder.

FWR: Not knowing the shape of the piece or pieces you’re working on about breath, I think of the attention there to the minutia or what feels like a mundane aspect of the body. It feels so simple, and yet if we were to stop, suddenly we have a big problem!

ET: Yeah– or if someone stops us from doing it. We take it for granted that it’s always here, but it’s here for you and me, but not for Black people, all the time. I love how much attention poets give to the body, in the here and the now, but I also want to give us the ability to think of the body beyond the physical body, as well. The body will fail us at some point; that’s written into its DNA, it’s not meant to be here forever, but how can we still give attention to the body when it is not here? Breath as well– it’s something but also inherently nothing.

FWR: Right, it goes back to what you were saying about the bowl, being the absence and the presence of something.

ET: And then what is the human body if not a bowl for air?

FWR: Or a bowl for memory, for experience…

ET: Right, and that’s the idea of mindfulness in mental health. Things will come, things will go. You experience them as they fill the bowl. It’s ok to be sad as they leave the bowl, and the bowl can be filled again.

FWR: I think this connects back to the idea of teaching grief. The emotions you are feeling in that moment may not last or may be tempered, and experiencing new emotions or developing new relationships does not mean that those previous ones have vanished, only that new relationships or feelings are coming in and adding to that space within us.

ET: Right, it’s a kind of object permanence that we’re always learning. This reminds me of what we were saying earlier about schools being open, and that they will probably close again. Will we look at that moment as a disaster, or will we look at that time together as something it’s now time to move on from as we approach a new situation and appreciate that situation for what it is, at that time.

FWR: There’s a connection that’s at the edges of my brain between what you’re saying and the fight for racial justice that is making its way through the country. So much of it is connected through video or social media records, and yet these are resulting in real actions that are being manipulated again through videos, which then inspire other actions. It’s connections across distance, space and time.

ET: Inherently in that is change. The injustice that is here right now is not the injustice that is here to stay.

FWR: And yet it goes back to what you said about entropy, that things will want to revert back to that old world. So how do we make a new world in the shell of the old?

ET: Absolutely, and I think that is the idea of being present. Being present doesn’t mean being inactive, it means living in this moment and evaluating what you can do in this moment. What in this present moment is doing anything at all. It’s that narrative leap we were talking about. Leaps are uncomfortable. If I don’t understand how a line can go into the next line, I can be delighted, but I can also be a little bit offended.

FWR: It’s that act of trust again, to believe that there is something on the other side of that gutter or narrative leap.

ET: That’s the job of the artist, to say I’m building the next breath for you, or the next content for you. Isn’t that an act of justice? To say that I guarantee my fellow human being has another breath, whether that be in racial justice or in terms of coronavirus? Why do we create art if it is not a self-perpetuating action?

That’s the job of the artist, to say I’m building the next breath for you, or the next content for you. Isn’t that an act of justice?

FWR: Are there artists or writers who are doing this work, or serving as guideposts for you?

ET: I feel like I am perpetually in debt to Ocean Vuong: he blurbed this book, he tries to bring up a multiplicity of artists, and he also picked my chapbook Revisions for Sibling Rivalry Press. And then I catch things he says off hand, like he was saying why people wear slippers in their houses is not to keep the outside world from coming in, but to show respect to someone’s stuff. He was saying that the reason he speaks so quietly is because he wants his voice to wear slippers in the world. I feel like that has influenced me a lot. More actively, Danez Smith, who is organizing in their local community and has raised something like 40 or 50 thousand dollars to do racial justice work in that area.

FWR: I see both of those writers in your work, especially as I think both are poets who are so interested in exploring and preserving a sense of self; each has a willingness to put oneself at the forefront of one’s writing.

ET: Yes, and a lack of apology, which I think is probably the most important thing. I think many artists, and I include myself in this category, can tend towards emulation. But emulation alone, I think, can serve as a sort of apology for yourself. I think a lot of us have imposter syndrome. It’s been interesting that some of the poems people have gravitated to have been poems I’ve never submitted for publication, because they felt too something– too something that I wanted to hide, or sneak into the manuscript. And yet those are the ones that people have brought up. The book is very personal, and for people to feel reason to talk about any piece of the work, but those in particular, has been very moving for me.

FWR: Is there one of those poems in particular that jumps out to you?

ET: A friend of mine experienced one of the first big losses of his life, and he sent me a photo of the poem “Closure”, which is a poem that I, I don’t think like is the word. I remember writing it and feeling like it was right for me, but it’s also very simple to me. I wish he was not feeling that loss or that suffering, and yet when that suffering happens, I feel both obligated to and happy to provide a tool with which to approach that tragedy.

FWR: Looking at the poem, it has so much we’ve talked about: the push-pull between absence and appearance– the airless kite, the mud prints– that threads so beautifully through the poem, even as the poem is also about moving forward and carrying griefs and memories forward. It’s a beautiful poem. I’m not surprised, but I’m glad that people are responding to your work and finding solace.

ET: As a debut full-length author, it feels like too much to expect such a personal response to the poems. We love accolades, or for someone to say something nice on Twitter, and those things feel lovely, but then once that moment is over, you go back to your everyday life. So, when someone reaches out, perhaps someone who maybe is not even a poet, to say that your book resonated with them, that, personally, is the most gratifying moment. That’s what poetry does– it reaches individual people, not just big swaths of culture. It seems strange because on one hand, those moments are not prestigious and on the other, they feel too valuable to reach. It’s very humbling.

FWR: I can’t imagine how having your debut come out against the backdrop of the coronavirus, how that might impact those feelings even further.

ET: Yes– initially I mourned the loss of a book tour and yet what has happened in response with my book, and thus my life, has been a rededication to racial justice. All the readings I’ve done online have been in some way related to that. A bunch of Western North Carolina writers and I hosted a fundraiser, where we used our books and our editing skills to raise money for organizations benefiting Black people. And isn’t that what I would want anyway? Can I imagine a better use for my art than benefiting the world in this way? So in that way, not thinking that ‘Oh, I don’t get to celebrate my book’, because I am. My art is existing in the space exactly where I hoped it would have. But in the previous models, pre-corona, that wouldn’t have seemed like a possibility to me. With this new world we’re creating, with our radical imagination, it is possible. Everything we do happens within a context. Our bodies, and beyond our bodies. Our breath, and our breath leaving us to intermingle with the larger world.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Christian Kiefer

Christian Kiefer is the director of the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at Ashland University and is the author of The Infinite Tides (Bloomsbury), The Animals (W.W. Norton), One Day Soon Time Will Have No Place Left to Hide (Nouvella Books), and Phantoms (Liveright/W.W. Norton). Photo by Christophe Chammartin.

FWR: Let’s start with your pieces for Literary Hub, where you focus on grammar as craft. Of Lauren Groff’s writing, you say, “The style of her sentences … are the gears and wheels of her genius.” Often, when we talk about craft, we’re looking at aspects of the form—point of view, exposition, characterization. I found it interesting how you articulated conditioning these components with the shape of prose itself. How does a writer go about using language and grammar to achieve a desired composite effect?

Christian Kiefer: I think the easy answer here is by consciously reading with language and musicality in mind. For me, the sentence length is effectively the length of breath that any piece of writing asks for. That length of breath can fluctuate depending on the scene or situation, but the exhale/inhale of a line of text is mostly dictated by its rhythm and its use of pauses and end stops (commas, periods—but also textual interruptions and so on). With someone like Faulkner, you’ve got an increasingly ostentatious use of clauses and phrases meant to contribute to the flow of the text so that the length of breath becomes almost laughable. For someone like Groff, you’ve got shorter, impactful clauses often fraught with a staccato rhythm that, even when rendered by soft syllabic information, is nonetheless possessive of a kind of wave-like feeling. One doesn’t even notice the periods, the commas, because the unit of rhythm is rendered so expertly.

There’s a whole list of “grammar rules” out there on the internet, of course, and once you have those under your belt, it’s pretty easy to see when people consciously break them. James Baldwin, for example, has a deep love of comma splices, which many college professors would mark as incorrect. Or Garth Greenwell’s idiosyncratic but deeply meaningful use of semicolons. Look at the rhythm of Jesmyn Ward’s prose, or ZZ Packer’s, or Michael Ondaatje’s. These are masters in how they employ grammar as a tool of meaning-making.

FWR: You’ve mentioned in interviews that when you’re writing poetry, you don’t think about narrative, yet the sentences in your novels are so poetic, such as this passage from The Animals:

Above him, above them all, the sky had gone full dark and stars seemed all at once to rise from the tops of the trees, their pinpoints wheeling for a moment across that black expanse only to return once again to those needled shapes, as if each light had come up through the soil, through the epidermis of root hairs and into the cortex and the endodermis and up at last through open xylem, the sapwood, through the vessels and tracheids, rising in the end to the thin sharp needles and releasing, finally, a single dim point of light into the thin dark air only to pull one back from that scattering of stars, the cambium pressing down the trunk, pressing back to black earth. Time circling in the soil and the silver tipped needles. Time circling in the big sage and cheatgrass of everything to come before.

The first sentence is a kind of blazon of a conifer, used less for exposition and more as movement. You’ve mentioned considering velocity as a specific approach to writing. How do you see poetic language as capable of creating certain motion? And in that way, how can lyricism serve narrative?

Kiefer: You’ve happened upon a great peeve of mine: style guides dictate prose should strive for clarity, as if poetry is the only form of writing that gets to be poetic. On one hand, that passage you quoted is perfectly clear to a plant biologist, although of course I’ve taken some license here and there, but its point and purpose is to sink the reader into the language of the natural world, a significant and meaningful (I hope!) theme of the novel.

The motion of the above passage is paused-for-breath by the commas, allowing for a lilting rhythm. I hone this by reading passages aloud over and over and tinkering with the rhythm and the language until it feels representative of whatever effect I’m trying to work toward. Sometimes it’s very, very conscious and sometimes it’s more intuitive, but most often somewhere in between the two.

Those last two sentences above are summatory of the long sentence that precedes them. It’s a way to nail down what might be to an average reader just a bunch of nonsense. I’m offering a way to anchor the reader to something a bit more grounded, though still representative of what the passage is “about”.

This is all to say that in terms of velocity something needs to be moving forward in the text. I’m a pretty patient reader but if there’s no apparent motion, I will eventually get bored. The writer has to put pressure on something—maybe it’s on the sentences themselves, but often it’s the characters, the situation, the scene. Hemingway is known for these short(ish), punchy sentences, but when in action scenes like the end of “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” he moves into a completely different rhythm, a completely different velocity

FWR: Your fiction heavily employs atmosphere. In your essay on Garth Greenwell, you call one of his passages a “stuttering delay on the details of the protagonist’s recollection and remembrance.” This relationship between the information released in each clause and what is concealed, to be released later, is a playful manipulation that lends itself to building the haunting atmospheric elements in The Animals, too. How do your terms “re-grammaring” and “re-informing” apply to your approach toward writing and establishing atmosphere?

Kiefer: This is probably something I learned from Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! Faulkner gives the reader so much information right from the first couple pages, yet the reader is totally flummoxed as to what is happening. Even at a basic level, the reader can hardly situate herself in the text. An elderly woman is sitting in a room telling a disjointed story to a college-aged Quentin Compson (from The Sound and the Fury). It seems like it would be straightforward, but part of Faulkner’s interest is the assumptions made by survivors of the Old South, such that most everyone knows the same characters and situations, and so Rosa Coldfield’s narrative—a narrative later assumed by Quentin’s father and by Quentin himself—is therefore fraught with assumptions about the knowledge of the listener/reader.

What this all amounts to is a text of accretion, the meaning of which deepens in spite of (or perhaps even because of) the reader’s confusion. It’s a miraculous thing and an almost impossible book to read, let alone write. I think I’ve probably read it ten times or so.

Having said that, I do think it can be very problematic to willfully withhold information from the reader, especially basic information. For those of us who are not Faulkner—and even Faulkner is not always in full possession of his talent—it’s important to set the reader into a situation or scene that is apprehensible. It can be terribly frustrating to read something and have to struggle to locate basic information. Absalom, Absalom! works counter to this because it’s very much about the act of storytelling over the gigantic canvas of history.

And thank you for your note on my use of atmosphere in my writing. It’s the part of the work that I most enjoy, which mostly comes late in the revision process. I’m doing 30 – 40 drafts of my writing, generally speaking, and a lot of that is dialing in specific textual effects and making sure that the setting is solid enough to be imagined but gauzy enough that the reader can also imagine her own version of it. In this sense, concealment can allow the reader into the text. In The Animals, I want readers to be able to envision the Nevada desert, but I also want to make sure it’s their own Nevada desert, not necessarily mine.

FWR: In Phantoms, characters and events parallel each other throughout, whether John Frazier and Ray Takahashi’s experiences in their respective wars, or John’s attempt to unravel the story of Ray against the backdrop of the town’s desire to deny it. Your syntax often mirrors this parallelism, as John views himself in opposition to or in league with different characters. Can you talk about how prose can embody what it is in fact describing, and how the goings on of a story might be inspired by its prose? How would you advise writers to play around with the tension and congruence between prose and content?

Kiefer: I would advise writers to play around with everything. In terms of the specific question, there’s a balance needed that is embodied in the syntax itself. Whenever you veer from the arrow of the narrative, you’ve got to remember that the reader is likely waiting for the text to reconnect with that (perceived) forward motion. As a microcosm, consider an individual sentence. “Once he awoke from his nap, Bob, still hung over from the night before—that last flight of whiskeys had clearly been a terrible mistake—returned to the office.” So what’s happening there is you’ve delayed the subject’s sentence by 7 syllables, then provided the subject, Bob, which immediately sets up the reader’s expectation that the verb is coming, which you’ve then delayed again by 25 syllables. You’ve got to make sure you’re deferring the reader’s grammatical satisfaction for a good reason. Too much of that will come off as an affectation. (Late Henry James is really, really good at this kind of thing.)

On the other hand, if you’re dealing with a scene where the protagonist is trying to avoid talking (or even thinking) about something, then the syntax—even in exposition—might start wrapping itself in circles in order to display something regarding that state of mind, delaying and interrupting, and so on, so that the reader can feel the reticence and avoidance without you having to state it. That’s a fine line to walk because it’s so easy to overdo.

FWR: You play around often with point of view, too. In The Animals, Nat’s perspective is in second person, and you write from the perspective of Majer, who’s a bear. Both Phantoms and One Day Soon Time Will Have No Place Left to Hide feature first-person plural, which in the former creates tension between community and individual and in the latter calls attention to the (inter)viewer and the nature of an artistic lens. What is point of view’s role in situating a reader closer to or farther from the text or characters?

Kiefer: This is something I’ve thought about a great deal. Pam Houston is the master of the second-person narrative, so I’m certain I learned everything I know about that from reading her work. Going back to Faulkner: he employs first-person plural often (look at “A Rose for Emily,” for example). Point of view is, for me, a decision of where to place what John Dos Passos famously called the “camera eye.” That placement can be very idiosyncratic and can even be off-putting (I remember Tin House-editor Rob Spillman commenting that he generally finds second person difficult to pull off).

What I’m interested in is using point of view to shift the position of the reader vis-à-vis the narrative. If we move from standard third-person past to second-person present, that does something significant to the flow of the text and the reader’s position to that text. The reader has to recalibrate where he thinks he is in relation to the story, which I find wonderfully invigorating (as a reader). Ondaatje does this kind of thing with scene, situation, character, and time when he shifts us into some other point in the timeline or shifting the entire narrative as in Divisadero. It’s a way to force readers to reapply themselves to the text while questioning what narrative is and what it can be.

FWR: I want to talk more about the filmic nature of your writing. One Day Soon Time Will Have No Place Left to Hide is described as a kinoroman, or a cinematic novel, and within it the narration functions at once as camera, us as collective readers and viewers, and words, as this is, of course, a book:

When she moves away we do not follow but watch her, receding, pulling out of focus as she reaches the glass doors of the casino, the reflection of the parking lot shifting momentarily across her disappearing shape. In that reflection is all of Nevada. In that reflection is you, reading these words.

Soon after, we read “We have not seen her smoke before, but she is smoking now.” This conflation of a literary feature like backstory with a note I’d expect to read in a screenplay functions as a sort of formal synesthesia. How do you draw from other creative formats in your work? And in your mind, what even is the role of form when it comes to writing?

Kiefer: I think it’s important to occupy “the arts” in a deep and meaningful way and to make sure you’re exploring how the effect of one work might be achieved in another. Like how might one create the textural quality of Anselm Kiefer’s (no relation) The Orders of the Night with words? Or the hauntingly floating opening of Hans Abrahamsen’s opera Let Me Tell You. Or Kehinde Wiley’s official portrait of President Barack Obama. That portrait makes me tear up. How could I as a writer accomplish the way it does that?

Obviously these are shifty questions. Kehinde Wiley’s portrait is wonderful because it can’t really be accomplished any other way, but I do think it’s useful to consider artistic borrowing in this capacity. After all, one isn’t trying to replicate the actual painting or music or text or film or whatever it is, but rather the feeling of that form.

FWR: John states early in Phantoms that “much of which [has written about Vietnam] helped [him] understand what happened over there and how the heavy stone of that experience continues to ripple out over a life that has been, at times, troubled by its own hidden currents.” This understanding of the Vietnam War helps the reader understand the domestic violence between the white and Japanese-American families of Newcastle as “a legacy of sanctioned violence both subtle and overt.” The formal can be of course akin to the traditional. So how can writers use formal conventions in a way that allows us to also re-understand and re-experience them?

Kiefer: At heart, I’m a traditional narrative novelist. The formal conventions are there because they work, but their existence also allows us to push against them, sometimes pretty hard, which is to say one can break herself upon the rocks of formal conventions. Despite the violence of that metaphor, I actually mean it to be positive: breaking in the sense of breaking open.

One of the things that formal conventions made possible in Phantoms was the direct critique of whiteness. A certain kind of America loves its nostalgia, but nostalgia for, say, the 1950s, a nostalgia that is also pre-civil rights, which is to say nostalgia (and especially nostalgia) can become a tool of white supremacy. So I’m writing about the Japanese internment and the American war in Vietnam, all of which is held in a traditional structure strong enough to push against—both in terms of the structure (which does shift and turn from time to time) and the themes.

FWR: Kirkus Reviews describes One Day Soon as an ars poetica, and your reflections on the creative process are refracted in the many ways in which you participate as a writer, musician, educator, and editor. Similarly, your writing encapsulates your interests, from being an ardent nature lover to having studied film at USC. Does writing have a requirement to in some way reflect on itself as a form of expression? And what then is the role of the author to do the same?

Kiefer: I’m not entirely certain how useful it is for writing to comment on writing. I don’t, for example, find traditional “craft” books to be very useful, nor do I much enjoy books that swing toward self-reference or meta-textuality. I already know I’m reading a book, so pointing out that I’m reading a book isn’t of much value to me. On the other hand, I love Italo Calvino so maybe I’m full of shit on this.

I think more important is being open to the truth that there may be no requirements in writing at all. Blake Butler, Katherine Standefer, Tasmyn Muir, Sally Rooney, Rebecca Makkai, Matthew Salesses, Emily Nemens: these are all wonderful writers who are doing very, very different things with words all while fulfilling whatever “requirements” we might place on them (or that they might place on themselves). What I want, what I long for, is a full immersion of my heart in the deep red-hot center of the text. I’m in the business of breaking hearts. We all are. And to be broken in turn.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Rachel Eliza Griffiths

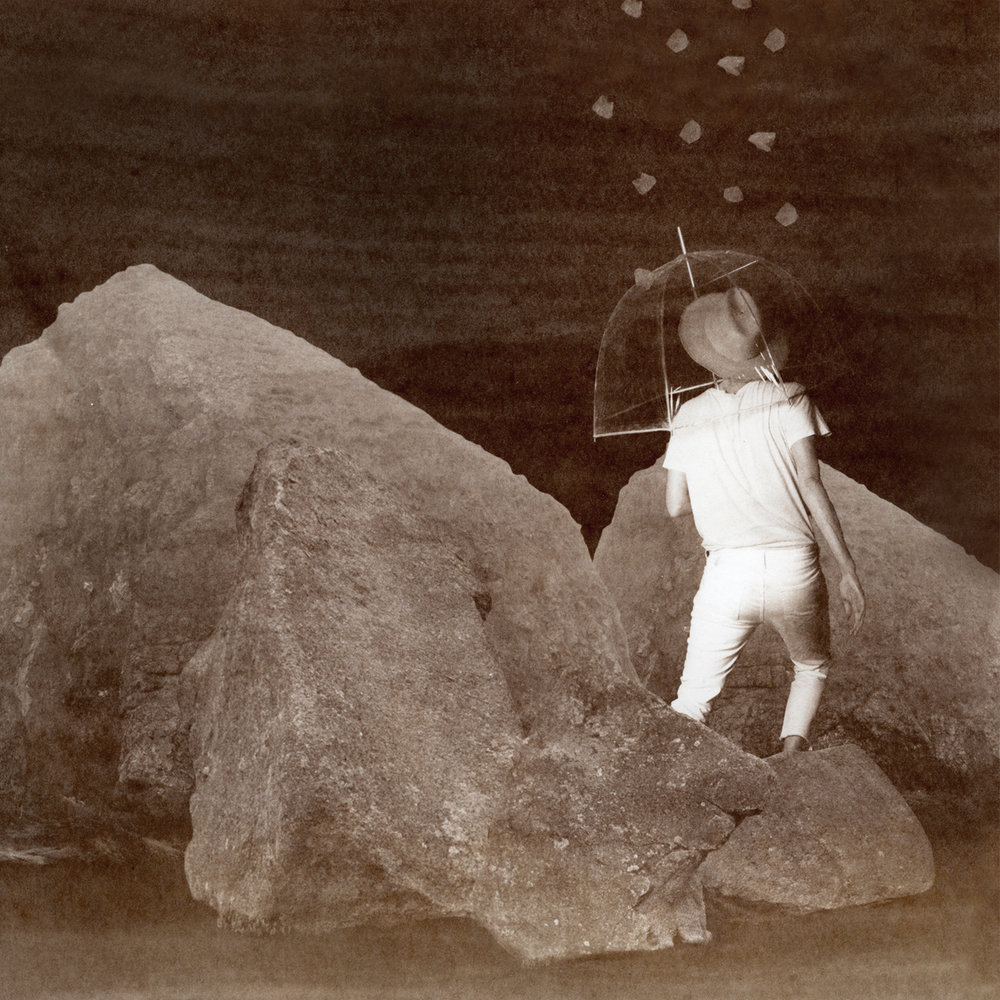

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a multimedia artist, poet, and writer. Griffiths is the author of Miracle Arrhythmia (Willow Books 2010), The Requited Distance (The Sheep Meadow Press 2011), Mule & Pear (New Issues Poetry & Prose 2011), which was selected for the 2012 Inaugural Poetry Award by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, and Lighting the Shadow (Four Way Books 2015), which was a finalist for the 2015 Balcones Poetry Prize and the 2016 Phillis Wheatley Book Award in Poetry. Her most recent book, Seeing the Body, is a hybrid of poetry and photography (W.W. Norton and Company).

FWR: I’d like to start with the titular poem, “Seeing the Body”. In it, you write into grief and how that grief can bifurcate the life of the living. In your visualization of grief, you create imagery (such as “flowers/falling from her blood” and “bale of grief on my back, opening/ into something black I wear”) that seems resistant to more common depictions of grief. (I’m thinking of poems like Auden’s “Funeral Blues” or the gothic imagery of Edgar Allen Poe, which have become synonymous with writing about loss). Did you find yourself resisting cliche, or writing through images that you had read from others, when you first began these poems?

Rachel Eliza Griffiths: The engine of “Seeing the Body” relies on how breathing happens through a poem as much as it is also about how breath stops or is altered by grief. There is the involuntary tension of trying to sustain an image or to construct a narrative about a beloved’s life or one’s self, only to find all is ruptured.

Auden’s wonderful poem is after something very different than “Seeing the Body” insomuch as Auden’s poem calls for a moment of silence that feels quite public in its address of ordinary life. My own poem wants intimacy, to address the earth and the private echo of silence where there is the sense of falling through one’s body, one’s birth and death through the body of the mother. My mother. This poem hurt me the entire time I worked on it. Years. I’ve never been attracted to clichés, visually or otherwise, so I don’t think about resisting them. What has startled and provoked me is the immediate emotional connection I feel wherever I share these poems. I’m writing about a “common” experience yet it is anything but common for me.

I can never read this poem as it should be read. That was intentional. Each time I enter the earth of this poem I am further away from its original grief. I am somewhere else in my body and can’t get back to the woman who braced herself against the initial impact of loss. Whenever anyone experiences this poem I hope there is an intimacy of reading that does not exclude our bodies. Through language, I’m aware of forcing myself to stop in the middle of something that has neither beginning nor end.

Listen to “Seeing the Body” read by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: Seeing the Body includes a section (“daughter: lyric: landscape”) composed of your photography, which is alluded to in other poems (“For years I photographed myself/ in a white dress”, from “Husband”). You write in your Author’s Note that these photos serve “as a map of the self and of the greater world in which [you] are both visualized and invisible”. Had you planned on incorporating photography from the beginning, or how did that process develop?

Griffiths: In the beginning, I didn’t plan to use any images at all in the book except I began to think about the types of photographs I had created in Mississippi just before she died. I had to go back and consider what I was “making” when I was unmade by her death. Then I also remembered the deliberate focus I gave photography immediately after her death. I clung to the machine, my camera, like a life raft. I began to perceive my own body as an urgent conduit of my grief, which meant I couldn’t leave my body outside of any landscape on the page.

Perhaps the only way now that I can truly see my mother’s body again is through studying my own. This time was weird and messy because I couldn’t read books. I had a hard time using my camera. All these tools were nothing to me. When I began to write about my mother, it was very difficult because it felt like language was forcing me to accept elements of her death I couldn’t bear.

Perhaps the only way now that I can truly see my mother’s body again is through studying my own.

FWR: Did this impact your understanding of or play with syntax? (I’m thinking here of the poems “As” and “Good Questions”).

Griffiths: “As” and “Good Questions” are fragmentary or function as what I might call a “collage of the lyric” — the rhythm and imagery bleed together in an attempt to both isolate language and to hold the visible language intact as grief itself opens through the body of the page. Photographs offered me a way to be grounded in the world, to remember there had been a world I loved before her death and that I could and must return to it. Finally, it was transformative, after so many years of being diligent that these mediums lived in separation, to ask them to touch each other and hold me.

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: “Color Theory and Praxis (I)” is a poem concerned with the body, but also the body in art. Specifically, it considers the painting “Open Casket” by Dana Schutz, which depicts Emmett Till. The poem questions who has the right to the body, particularly a body of color, and after death. I wonder if this influenced your own writing, as some of your poems see you imagining the voice of your mother, as in “Comedy”: ‘Yeah don’t go and write about me like that/ she says. I already know you will.’

Griffiths: I’m ambivalent about my relationship to placing myself inside the voices and bodies of others. I’ve done it, whether by persona or in certain photographic series, and it can feel tense for me. Issues of permission and imagination fascinate me. I’m not interested in policing anyone but I do have the right to challenge, to question, and to critique certain things, especially when it comes to visual arts and representation. There is a lot at stake for me even when it feels like people want artists to shut up when their work is confrontational. I read an interview where Schutz said the painting was about a conversation with Till’s mother. I disagreed with her perspective and the “terms” of this unreal, fantastical conversation, which placed the mutilated body of a black mother’s son as its focal point, as its medium. There is a photograph of Mamie Till at her son’s casket. I don’t feel like Schutz’s painting could ever listen to, or tell Mamie Till’s truth. The artist has a right to do whatever she wants but I tried to understand what and where that right was located. I mean, there’s a painting of hers that features Michael Jackson’s body on an autopsy table. Again, do what you want but do it well. Also, I noticed she didn’t use Trayvon Martin’s image, or Sean Bell’s, Tamir Rice’s, or Eric Garner’s, or Jordan Davis’, or Philando Castile’s, or Mike Brown’s, or Ahmaud Arbery’s, or…or…

I’m tired. There isn’t enough canvas, enough pigment, enough bones in this country for black artists to address the violence and harm done to our bodies, our communities, by the imaginations or institutions that can’t bear for us to live. It isn’t our job or our art’s job to do that work either. Why is America afraid that we dare to imagine ourselves as anything but dead?

My mother and I would go back and forth about my writing. Sometimes she’d ask me when I was going to write her story. Other times she worried about my imagination. None of the poems in “Seeing the Body” ever enter my mother’s body and use her voice. I never wanted to do that. The dialogue in “Comedy” was exactly what she said.

It isn’t our job or our art’s job to do that work either. Why is America afraid that we dare to imagine ourselves as anything but dead?

FWR: In “Good Questions”, you write, “when did the final arrangements begin? / At her birth. Inside of wet rock. When my birth began.” Throughout the text, I was struck by your exploration of inheritance, whether of womanhood or illness, and how grief lives in the body (as in “Signs”). Would you speak to the development of this thread?

Griffiths: I’m in a more explicit stage of my life where I want to think of myself within a greater dimension, in conversation with beings that arrived before me, and those who are already arriving after me. I think about what I can share with the living and the dead. I’m constantly aware that the earth is different in her temperament since I was born. I’ve been astonished by how quickly some of our geographies have reverted and have healed during the pandemic without the presence of human abuse.

At this point, my work lends me an expansive way to think about how I might, as an artist, establish or assert my own lineage or claim inheritance in ways that don’t necessarily include children. I’m constantly thinking about how remarkable it is to begin to really take into consideration the manners, culture, trauma, resilience, joys, and ways-of-being that I have inherited. These things I hold have come from my family but they have come from a larger consciousness. They also come from within me.

I’m in a more explicit stage of my life where I want to think of myself within a greater dimension, in conversation with beings that arrived before me, and those who are already arriving after me. I think about what I can share with the living and the dead. I’m constantly aware that the earth is different in her temperament since I was born.

FWR: Seeing the Body explores the shifting ownership of the female body and how language can free, as well as constrain. In “Ars Poetica”, you write of imagining becoming a writer or a woman like your mother, before the neighbor and his friend interrupt your daydream: “his friend braked hard,/ barking like a dog… Hey, Bitch, he said”. In “My Rapes” your mother asks, “why/ I listened to white girl shit. How could alternative music/ hear a black cry like mine?” Can language free us from the body?