SIX ECCLESIASTICAL LOVE SONGS by C. T. Salazar

heaven is a compound

word

the sun sunders

us dazzling

so you don’t have to

wonder what wound

I’m showing

:::

heaven-heavy

like

a cello’s hello—

/ heaven-heavy

like an animal fond of its own

fur.

:::

A cello’s hollow

that’s what it felt like

breathing with you

in the dark

:::

heaven is a compound

but not the one we’re in

we were called heathens in another myth

hello whatever wound we answer to now

:::

the language of electricity was

the language of prophets

a conduit for the power to pass through

I’m all steeple at your lightning

let us tremble cellos

at your touch

:::

the river knowing which way to go

without any godspeed to spill

heaven: clouds marigolding softly

:::

birds drones butterflies a jug

of water anything

could get over that fence

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Keetje Kuipers

IN THE OUTDOOR SHOWER WITH MY PREGNANT WIFE

The old frisbee from Burger Chef, once red

but faded now the pale pink of my wife’s

widening aureoles, lies upturned

beneath the saltwater drip of our sagging

beach towels. This world is full of objects

succumbing to the gentle ebb of decay. But her body—

loosening breasts and blue-veined thighs caught

in a cascade of wet light as she turns

beneath the showerhead’s senseless spray—

is not one of them. That low-blooming

shudder and heft at her hips can’t compare

to her belly button’s skin stretched taut

and thin, become the pale sail of a boat

screaming into harbor. I am here

to praise the way in which everything

I have ever loved about her body

is about to be ruined forever in the breaking

open. Tonight the wind will come up,

turn the towels on the line into fat bells,

churn the waves into a froth, drag the sand

out and leave it where our toes can’t touch.

In the morning, the ocean will return

to its languid sheet, but the beach will be strewn

with the wreckage. I want already

the body scarred by stretch marks, the extra flap

of skin to hang soft at her waist, the feet

that will never again be quite so small.

I want to worship the body after the storm,

the one I’m imagining already

as she unfolds the straps from her shoulders

and peels the suit off, her skin covered in

those minute and glittering fragments of shell

some people insist on calling sand.

WITH GARBO IN PALM SPRINGS

We’re at the resort, the one with the forty-one

pools, and it’s night so if we were up in the swaying

fronds of a palm tree the ground would stretch before us

a green freckled thigh against a dark sheet. But Greta

and I are inside, perched on the edge of the bed

watching my wife sleep. She’s beautiful, we agree,

and my daughter, too, their blond hair spread against

the pillow like a silk scarf in a silent movie.

Though now Greta’s impatient with all the watching,

the kid especially, so we go outside to smoke

her cigarettes, to lean our backs against the white

adobe walls and kiss for as long as it takes.

The electronic lock clicks behind us, a set

of perfect teeth, and I’m chasing Greta across

the lawn with its lemon trees I can smell in the dark,

past the lounge chair where someone’s abandoned

the sort of wide brimmed hat meant to keep us young,

over the patio still warm as skin from the sun’s

relentless shining, toward the place where she’s already

slipped off her dress and climbed into the water,

side-stroking with one arm and holding her smoke

aloft with the other. And if I say it’s a dream,

it will have no power. And if I say it’s real,

no one will ever believe me. But can’t it

be both? I want to rub my body against her

perfect one. So I do. All my nubbly parts sanded

down against the smooth monument of her form,

ageless as the desert once was before we came here

and turned it into a golf course. Now only

my hunger—its vast, unquenchable fury—

interrupts the glow of each long leg as she traces

eggbeater circles in the blue depths beneath her.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

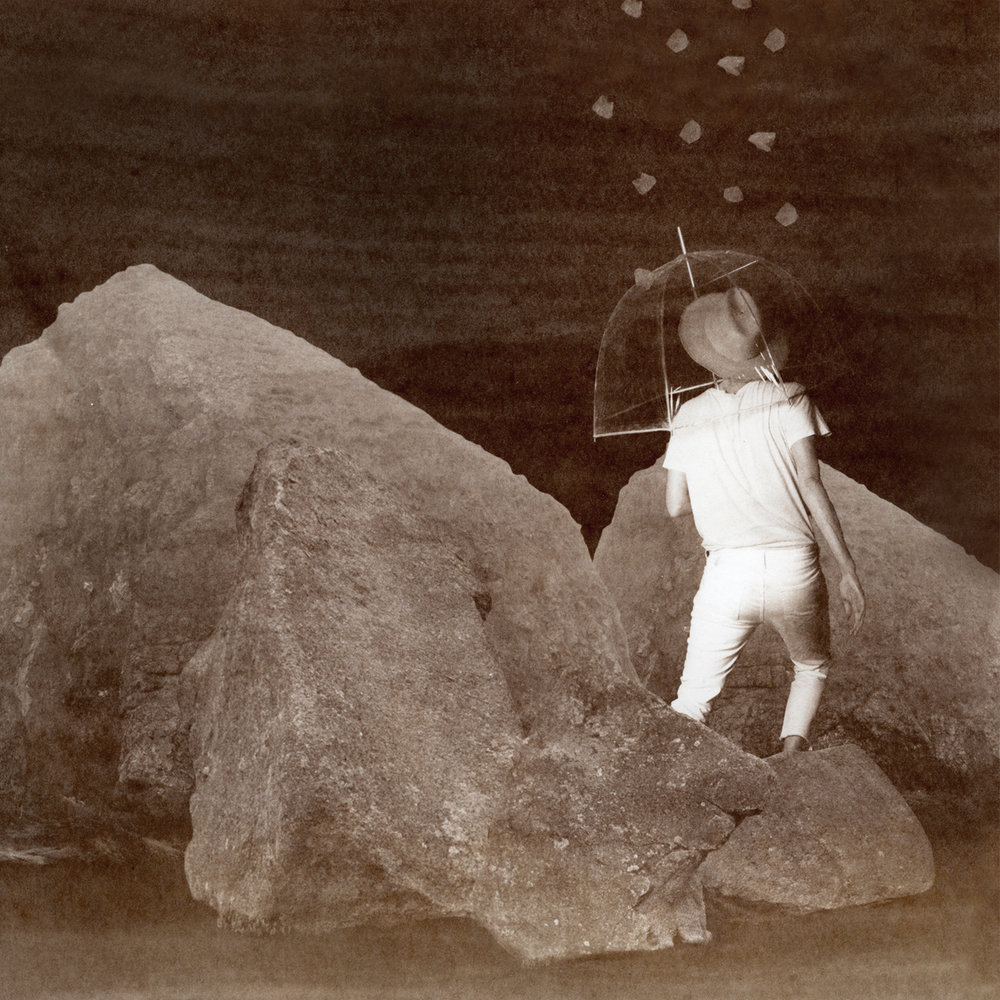

ART by Suzanne Koett

“Cone and Potholes,” archival inkjet print, 11″ x 17″, 2017 by Suzanne Koett

“Track 3: The First Season,” digital, collage & Vandyke brown print on archival watercolor paper, 8″ x 8″, 2018 by Suzanne Koett

“Fox,” Archival Inkjet Print, 11″ x 17″, 2018 by Suzanne Koett

“Powerlessness,” Archival Inkjet Photograph, 20″ x 30″, 2014 by Suzanne Koett

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Jessica Johnson

UPDATE

The boy builds a four-throated fish

out of cardboard. The fish lips

flap, blue-taped, from a body that

carried bottles. See! He says

a large-mouth bass. I’d have smiled once

(inwardly of course) at his fine

imaginary, thought him unspoiled, amusing himself

with the trash.

Wasn’t I doing a good

job? The boy, a living sign that I could refuse

the invisible purveyors who would sell him

dopamine hits & strangling masculinity with a side

of fried sugar? The things we buy

without knowing. But this is a cool

summer, air and skin the same, enough water

the rose taller, the jasmine tendrils

longer. The soft white sky.

I ought to love it. There’s no war now

except the usual one

& death like age is just a number

that rises. I walk every morning

& the number rises. We finish our assignments

& the number rises. We reply to your message

& the number rises. We build a fire no one

may gather around. What can you swallow

with four throats

that you couldn’t swallow with one?

The same things, but smaller.

BAD INSURANCE

One trimmed off his own name

to hide his Irishness.

One wrote white

instead of mother’s mother was

instead of no

right designation. One dressed

like a shark, smooth suited, pressed

& pale to compensate

for parents who grew

in foreign soil

on preserved fish & sometimes stank of it.

My people were damned

successful at leaving themselves behind

rushing toward a shrinking

field of safety just inside the blade

of cooling sunlight even

as night came on.

And me, years ago when I had bad

insurance, I saw a doctor for a raft

of pains, a strange doctor

but official. She said the way I move’s all

wrong: from the edge not the center

as if I could just decide a thing & make it so

without getting too close without risking parts (belly, heart)

I couldn’t lose.

She said my problems come

from a thumb too quick

to pin something under it.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

I USED TO PRAY by Yuxi Lin

to any God that made me

feel ashamed.

Girls are takers,

Mama used to say.

I took every lesson

she gave me, learned

to swim out of my body

& abandon it.

With incense I burned pages

until a perfect eye stared back.

God drilled a hole to make us see.

See? Mine is filthy.

He, too, eyed me

each day afterschool,

clutching the line to the lure.

When I walked by

he’d catch me & groan

Oh you’ve grown so heavy.

Like his breath, his fingers

were meaty & thick.

For years I weighed myself

then I weighed myself down.

In the water, my scaled body

lay bent & murky.

Listen — Don’t believe in God

unless he admits

he was always watching.

Look back at him.

If he had my courage

he’d choose to be born

a daughter.

What am I begging for?

I have two mouths.

One remembers.

Neither forgives.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

MEMORIAL DAY by Chelsea Dingman

Not the storm, but the calm.

Not the flurry of attention

called to the sky.

Not the rumour of a hurricane on the horizon.

Not humidity, the mosquitoes rising

like smoke from the fields.

Not a history of revisions we call

love, or survival.

Not the children lost and discarded.

Not the borders that hostage them.

Not how we were once possible

under this tyrant

sky, the familiar sorrow of the fields.

Describe our self-importance.

This awareness that travels us like a siren.

Why the live oaks drown in brown pollen

gripping the streets.

Who else will wash this mess clean?

Laundry-damp, our houses.

Thick with spoiled food and loneliness.

In times of love and crisis, we’ve been

the most alone.

Planes take off without us.

Children flit between namesakes like wasps.

We miss what is ours while it is within reach,

along with the dim sound of thunder

in the distance, storm drains already chuffing.

Let any absence mean we are loved.

Let the rain come soon, and be done with us.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

VENUS DE MILO WITH DRAWERS: SELF-PORTRAIT MADE OF MINK & PLASTER by Caroline Parkman Barr

Each morning is the same

but I can’t help but look again and again:

skin smooth peony petal, vanilla-ice-

cream-cool; hair a ripple of milk pulled back

too tight (though sometimes I forget the aching);

even my eyes are eggshells. Only air where arms

should be, dimpled seams of unfinished

making I’ll never forgive, but the sling

of this sheet hugs my hips in the perfect

place that says, Hey, I can still be sexy.

Then, there are the drawers: forehead,

breasts, ribcage, stomach, my left knee—

the edges to my curves only someone else

can open—nipples, belly button, each knob

a puff of fur to touch and pull. I’m told

they’re so, so soft. Everyone wants to look

inside, and sometimes I let them

just to feel the rub and jolt, just to see

their faces when they find my secrets,

find their own. My favorite part is when

they shut me, shaking my spine so hard

I almost crack—and for a moment it feels

some part of me could change.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

A POEM WHERE GOD IS A PARABLE by Jay Kophy

The absence of faith is the beginning of death.

What I call flesh is prayer bound to my bones.

All my prayers begin as songs from my bones

and end with blood instead of amen.

How I wish I began every request with amen,

like when I ask God to let doubt pass from me.

Amen. Oh God. let this sea of doubt pass from me,

for I’ve tried walking on water & almost drowned.

In Noah’s ark, a lost name is replaced with drowned.

In Ghana, anyone who drowns is without a name.

What is the value of a life without a name

to those who believe in what they can only see?

To those who believe in what they can only see,

the absence of faith is the beginning of death.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

IF YOU ARE READING THIS by James Hoch

We are building a house

small in the woods,

refuge from disquiet

or vague boredom.

It must weather distance,

the hurt of proximity.

We do not mean to,

though we are so good

at breaking, scavenging

old bone and feather, stalks of

wildflowers outlasting

the hour of their heads.

You are boss, and look boss,

hammer and spackle knife

and blue hair, plastering.

At a window you like the way

open sounds, so you mouth it

until the word too becomes

some thing to occupy.

You can’t take it with you,

and the house won’t stay

when you’re gone.

Wind is saying this,

the way wind likes to say things,

likes the door swinging,

petals over the floor,

then floor, then house,

then whatever was before.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

BALIKBAYAN FILLED WITH THEORY by Dujie Tahat

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Ariel Francisco

DREAMING OF THE GOVERNOR AND THE MAYOR PLUNGING INTO THE RIVER

Perhaps conjoined at the ankle

by a concrete block, like the tails

of Pisces. Yes, let them embrace

the East River together in early

morning so they may be blessed

at last by the light of a new day

rising beautifully without them.

MY DAD’S BIRTHDAY IS WRONG ON HIS BIRTH CERTIFICATE BECAUSE HIS PARENTS COULDN’T AFFORD TO PAY FOR IT WHEN HE WAS BORN

Officially my dad was born

June 3rd, 1957— that’s what all

of his documents, signed and notarized

claim in both countries that claim him—

though unofficially, hearsay,

there’s no proof that he entered the world

on April 11th, 1957: photos can be

doctored and both parents dead,

only the scowl on his face when it’s

brought up can serve as testament

to those fifty-four unaccounted days.

There is being born into poverty

and then there is not being born

because of poverty. One must pay

to come into existence and my dad’s

existence was delayed two months

because his parents could not.

There is something unforgivable

about being denied time, about

being made to feel as though you need

to catch up to yourself, make up

what’s been lost— no, what’s been taken.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary

I do not like dwelling on the past,

especially one inherited so heavily

and without consent; but I can’t help

but think of how being a dollar short

seems to be a family trait, of how

my grandparents split, fell apart

like dead trees in a storm, of how

my dad grew up to meet my mom

and repeat that cycle, unintentionally,

but intentions don’t matter when you’re left

indebted to the wreckage—

of how things could have been different

of how things could have been different.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

TWO POEMS by Melissa Crowe

SOBRIETY SONNET

with apologies to my brother, 11 months clean

The boy who cried sunlight, summer rain,

bird-in-the-bush, in the hand, who cried

fiddleheads, brook trout, berries in the field

by the chicken house, again and again

who cried lilacs, from each bloom

a hit of nectar and nothing to fear—

he’d pretended for so long the all clear

while something hungry paced the room

that even when of true wolflessness

he made a bouquet so pretty and perfumed

nobody in her right mind could presume

it wasn’t flowers, I called it beast,

saw in the gold-dusted mouth of each bud

a dogtooth sharp enough to draw blood.

EPITHALAMIUM WITH PAPER BELL

I was there on the day my mother married—

I’ve seen photographs of her in her borrowed

dress, bodice of a taller friend wrinkled

at her waist, slack satin pooling at her feet.

Her forehead shines above a startled smile,

and my sudden stepfather, in a rented tux

of powder blue, just looks glad. There I am,

too, tucked between them on my final day

of being five years old. I don’t remember

the ceremony or the reception, the kind I’d

later love when my mother’s younger brothers

wed their first or second wives at the Elks club

or the VFW, center of the room cleared

for a dance floor, tables pushed to the walls

and spread with crockpots of cabbage rolls,

spam salad spooned into hotdog buns.

Beer bottles and ashtrays. Uncles with their

sleeves rolled up, Red Wings buffed of mud.

When they weren’t twirling girlfriends

with spaghetti straps and long-long hair,

pulling them close for the slow tunes,

they lifted me into their arms so I could hug

their whiskered necks. There’d have been

a deejay and gallons of milk mixed with Kahlua,

a dollar dance, man after man paying to twirl

my mother a little, money for the honeymoon,

one night in a cabin at Portage Lake then back

to the shoe factory. But I only remember

the paper bell I found taped to a table that night,

miracle the way I could close its feathers so

easily, conceal the whole voluminous thing

between two half-bells of card, then open it

as swiftly as lungs can fill with breath.

Like hands that part to reveal what I’d

wished for bent at the bedside, what I’d seen

in my head and whispered into the dark.

I could almost have believed I heard it ringing,

that tissue bell, marvelous flat nothing

come to song. I kept it a long time, precious—

and then I guess I lost it. I guess we all did.

- Published in Issue 19, Uncategorized

- 1

- 2