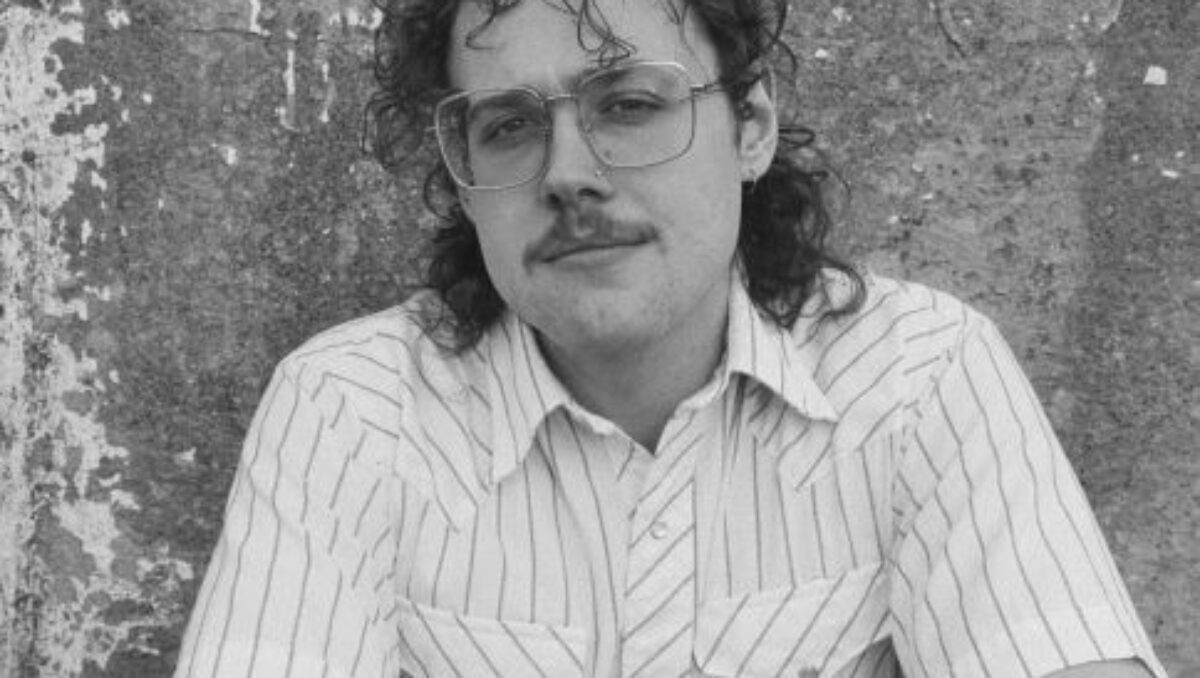

FOUR POEMS by Alexander Duringer

The Poet

Where the poet is, everything

glows: red-capped forehead,

peppered beard. He holds a torch

to frozen streets that truss his lines,

writes temptations of the pool

glazed by a boy, bright & soft.

He traces new constellations

into moles on the backs of men

asleep upon his stomach. In one

of his failures he drank

blood from the fountain of a god’s

absent head, wrote of its stooped father,

starved with worry, feral-mouthed

as he scraped into the son’s muscled back,

the way one undresses an orange.

Here, concealed, a question mark–

the curved neck of a blue heron

I’ve observed unfold its canopy above

a pond, stilt legs still, in the water.

The shade it made lulled ducklings

onto its spear that pierces me,

too, & may swallow me whole.

The night breeze is so clear &

I could not hear my father

through the trees. He liked to fly

kites with me–Labatt

in one hand, string in the other.

He held the cool can to my lips

when I tripped. Blood mottled

in my mother’s hands & I can hear

a child scream. I am glad

he is alive. I have said

goodnight to many moons

& will become a squirrel with its nut

& bury this one, too, lose

its scent & starve. Now the wind has

quieted, the child’s tears are dirty

streaks as parentheses of bodies

cleave together, legs tangled

like crashed kites. Those rainbow

calamities. Jesus christ, so many lines.

The Queer’s Epithalamium

There I am, in the broken swan’s neck

of a pocket square & bridesmaids’ navy

blue at the ends of all

the photographs. I walked the couple’s pug

down the aisle. A little joke

that made aunts on both sides say, Aw. It wheezes

with me in one photo with confetti

& champagne. My boyfriend wasn’t invited.

You don’t mind, right? Who would he talk to?

& it’s a hundred a head. I try to resist

the word, faggot, in poems. How trite,

but that’s what the groom called me, cock in hand,

spraying piss at the urinal, eyes on my lips.

The Prostate

I sat on everything

when I learned how men came together:

yellow squash from the fridge,

plunger handles, my

fingers buried inside to push

& rub, slick

with the medicine cabinet’s vaseline

in search of that tender

walnut, its nerves & lobes,

shucked snake fruit. Subtle

universe, expansive

button toughened

with age. It’s a rude

subway passenger who spreads legs

& clogs pipes; little pleasure,

little tyrant, Caligula

at war with the Tyrrhenian Sea

atop his senator horse.

A doctor once examined me

with latex gloves. His left

hand’s index finger jabbed

so hard that I bleated clear,

involuntary, ejaculate. The bruised

bit pulsed later like a larval sac. Too bad

my brother might never see his

as more than the lisping shadow

in a noir who reaches

his effete fist toward

a pistol on the nightstand.

Within me, you

explored its puppet-mastery

over my body’s parts. Mouths & tongues

formed new vowels.

Toes curled as you made

its strings move my palm along

your cheek; pressed against that uncut

diamond hidden so deep

some might assume it was ashamed.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Poetry

TWO POEMS by Zuleyha Ozturk Lasky

Severn, Maryland

pink mouths of crepe myrtle mouthing words like çay demle kızım and a sloped garden in the back and a creaking deck and a bookshelf full of religious texts and my bedroom in robin blue and hairbands always lost under couch cushions and prayer rug facing the direction it’s supposed to face and me facing the opposite way and prayer rugs quartered and stacked in a pile inside the tv console and prayer beads hanging from lamps and Keurig machine and milk frother and two teapots (one electric, one traditional) and windows facing trees and grape leaves brined in jars and fig jams lined on the shelf and sink full of dishes and when washing dishes a window facing the neighbors pool and my father asleep and overworked on the couch and a bowl of seasonal fruit and my mother asleep and overworked on the couch and my sisters whisper laughing and pantry full of turkish sweets and sunflower seeds and gallon of olive oil and lentils and dried mint and fridge that always hums past midnight and tv tuned to politics or a movie and fly always buzzing and a trail of ants that will never leave

Hyattsville, Maryland

a teapot recently bought from turkish market and sunlight slipping through slats like ballet dancers and three lemon sprouts and a balcony to count the balcony dogs and the sunflowers painted on a ceramic plant pot and next door neighbors with their balcony door open and my first ramadan away from family and our neighbors wake up with us during a salted night and ezan waltzing out their door and dust on our bookshelves and your phone in pool and our studio with high ceilings and built-in granite desk which is technically a bar corner and Beatles poster with fox-gloves that become jellyfish when dropping acid and so much time to graze on your lips and quarantine thanksgiving and quarantine work and quarantine writing and quarantine walks and masks forgotten in pockets clung to dryer sheets and sick three days after vaccine and sick three days after wedding and impromptu Ocean City trip where we ran under kites shaped like our laughter and so many matchbox apartments with high ceilings in gentrified neighborhood and mid-day walks to Vigilante to order americano and latte and somedays there were two or three walks just because and no one on the streets and walks near the railroad tracks and the apartment our home now with our fortune read in coffee grinds shaped like fish and look how they feel swimming under our feet

- Published in ISSUE 27, Poetry, Uncategorized

THE POINT OF ARTICULATION by Car Simione

To prepare for the apocalypse, I practice looking

in the mirror. I kiss myself on the mouth. I practice

hopping on one foot, but the eventual sight of you

nosing among the lilacs nearly topples me,

so I excavate the marketplace and poll

the dignified masses in their plaid coats. They ask

for more time. Despite my ministrations, the flowers

keep dying. Despite my ministrations, the certainty

of uncertainty continues. Romantic, tossed, I bet

on your five good molars. I forget to cheat.

In the fashion of a man, I perform the proper rites.

I stow the long boxes in the graves. I shimmer

in the bat cave. I croak and insects gather

along my pink tongue. A few words swell.

TWO POEMS by Sophia Terazawa

Residual

These syllables strike our lower

register [branching: fog]. Who whispers

like a friend, “Bêche-de-mer,”

I wring out towels and pillow cases.

Sunday afternoon. Check on

your sister, you sign. She won’t speak

anymore. Glass trees.

Soapstone box. You package her father’s

old shirt there in Queens

[arms crossed at the chest] posing

unpalatably. I imitate you

imitating him like a tourist on the tenth

night of spring in a country bent

to numb what could hurt but doesn’t.

San Simeon

Dionysus, get up. Your friend is here. Smoke

on the portico, leafless, head to toe in gold.

Angus cattle roam past tomorrow,

startle into place; this home, measured by this

low thrumming. Get up. Wash your face.

Honeycomb patterns a handkerchief

rave, though he’s not my guest.

I won’t let him in. Hurry, mind the blue

marble. Sweet smoked hickory is a sarcophagus

between rooms cracking. This year

love will find me ready for it

helping ma with taxes. 24 adorned faces

will make a sentence, the old kind.

Suppose I wait longer than I should. Eve,

Oshōgatsu: oh, interminable want.

(JANUARY) by Hanna Riisager trans. Kristina Andersson Bicher

I see the subject all

the time in front of me, see all these

small rituals.

How it lies on the sofa and waits

for me to come.

The wind pushes moirés of ice and snow

against the windowpane. An undulating, pearl gray surface –

silk bark.

My brain’s pale tissues

unfold in the room in a billowing mass.

I’m floating under the roof, looking down.

The subject stays on the sofa. Smoothed

waxed, with a distilled stiffness

in the facial musculature.

I smile. Hug

the clots of the heart, my dark charms.

Kristina Andersson Bicher is a poet, essayist, and translator. Her work has been published in AGNI, The Atlantic, Ploughshares, Colorado Review, Brooklyn Rail, Harvard Review, Hayden’s Ferry, Plume, Narrative, and others. She is author of the poetry collection She-Giant in the Land of Here-We-Go-Again (MadHat Press 2020) and Just Now Alive (FLP 2014), as well as a translation of Swedish poet Marie Lundquist’s I Walk Around Gathering Up My Garden for the Night (Bitter Oleander Press 2020).

AROUND THE FIRE by Gloria Susana Esquivel trans. Joel Streicker

“En llamas será la canción”

Briela Ojeda

Everything was in flames.

She felt a slight burning in her eyes and thought, for an instant, that the smoke choking the images on the TV had filtered into the room.

She blinked, then turned her attention back to the newscast. Ten million hectares were burning uncontrollably. The world ablaze.

She tried to grasp the magnitude of the disaster, imagining the fire spreading through all her belongings. Her clothes, her daughter’s toys, her husband’s shoes, the air fryer—all of it in flames. All the kitchen gadgets that she’d bought in the past year—because she’d promised to be the type of mother who baked homemade cookies and cakes for her daughter—and that had never been touched, blazed in her mind in just the same way as the bamboo forest.

The red light of the TV bounced off the room’s white walls, casting them in a warm glow. But she felt cold. She remembered that she was naked and that it was raining outside. She covered herself with a towel and sat on the edge of the bed. On the screen, the mass exodus of animals played on repeat. A koala clutched onto the highest branch of a tree that would soon be laid waste. She searched for a glimmer of terror in the animal’s eyes but found only blackness. And then the red, the yellow, and again the red devoured everything. She glanced down at her legs, which trembled slightly, and found traces of a bite. She rubbed her skin, trying to make the mark disappear, but the cool surface of her thigh wouldn’t cooperate.

She closed her eyes. She tried to recall the aroma of cinnamon and butter cookies that she had promised to bake, tried to recall her husband’s smell. But the only thing she recognized was the odor of cigarettes in her hair and a taste of rust on her palate. She hadn’t had much to drink that night—not as much as the young man—but the sour taste of alcohol and pills had settled in her mouth. Feeling nauseous, she opened her eyes. The landscape stretched out on the TV screen. A red line, very bright, divided the darkness of the earth from that of the sky—like a streak of light in the night or a very red tongue on a pale torso.

The phone rang.

On the other end, the voice of the man at the front desk sounded harried. She kept her gaze fixed on the flames invading the screen. It took her a few seconds to understand what was happening. She came back to earth as the voice explained that the young man’s credit card had been declined and that the hotel needed some other form of payment. She climbed out of bed to fetch her purse, availing herself of the TV’s blue brightness to search for one of her cards. She began to dictate the numbers slowly in an attempt to stop the frantic stream of words coming from the other end of the line. When everything was in order, she hung up.

She got in the shower.

The mark on her thigh spread as soon as the hot water hit her leg, and she had a vision of the young man crawling over her thighs. She closed her eyes and let herself be carried away by the sensation of the water hitting her back. With the impact of each drop, memories of what had happened that night reappeared. A couple of drinks. Kisses inside a bathroom stall. The impulse to escape to the nearest hotel. The neon light of the front desk hurting her eyes, its bright white flickering deforming the face of the young man. She opened her eyes and turned around, facing the showerhead, then parted her lips to receive a mouthful of cold water, remembering the touch of that other skin. Her desire to lick it. To bite it. How she succumbed to instinct and nibbled on his ears. She turned, enjoyed how the water slid over her buttocks. She thought of how she’d dug her nails, and then her teeth, into him, and how he hadn’t put up any resistance to the blade of her incisors. She was still hungry, but it was too late to find anyone else and no restaurants would be open. She turned off the faucet and covered herself with the towel again.

On the screen, the orange sky seemed to announce the end of times. A few men fought against the flames, but their efforts seemed futile. The force of the water expelled by their hoses was puny compared to the magnitude of the disaster. She saw the screen of her cellphone light up and, curious, she approached the night table. Fifteen text messages and twenty missed calls. Maybe her husband had forgotten the good-night conversation they’d had? She’d known him for seven years and, during that entire time, she had tested out a large repertoire of excuses and lies to keep his questions at bay. Work trips. Visits to her mother. A yoga retreat that promised to align her chakras. Lying to him was a matter of life and death. How else was she going to maintain her sanity? She needed to get out of the house at least three times a year. She needed those feasts of young flesh.

Everything was a question of balance, she told herself, each time she returned home sated after one of those hunting expeditions. She would kiss her daughter’s head and ask her husband to watch a romantic movie with her—sometimes she even offered to make popcorn—and forget about everything else. The looks. The touches. The fingers submerged in mouths. The nakedness. The blades and the bites. Sitting on the comfortable couch in her house, it was hard for her to recall the flavor of blood, the taste of rust that clung to her teeth, much less the fibrous texture of the young men with whom she satiated an ancestral hunger.

She lay back in the bed and began to examine the messages exploding her phone.

At her side, the body of the young man lay immobile. The image of a desolate highway sent a strong shudder through her. What had been trees were now frail black lines barely managing to remain upright. The cameraman had captured a white horse galloping, terrified, and an orphaned kangaroo in the immensity of the red landscape. She felt the impulse to talk with the young man about what she was witnessing, but the images of smoke swallowing everything up distracted her. She took a deep breath. Her husband had linked the credit card to his cellphone and had received a notification of the transaction at this downtown hotel. She felt herself observed, but instead of shame, she felt rage. Hadn’t those silences given them a quiet life? What did he gain by tracking her? Was he ready to burn everything down?

The first messages had a worried tone. She recalled the koala’s empty gaze, then the young man’s look of terror, and thought about how her husband’s eyes always seemed blank. The best thing to do would be to think of a lie. Tell him that her credit card had been cloned, and that’s why that transaction for a room in a sketchy hotel was appearing. But the messages that followed were a torrent of complaints and demands. He had called her friends. Her mother. Nobody knew where she was that night. No possible lie would pacify the anger of that man who had left voice memos full of fury. He gave her an ultimatum. He would call the police. He would go look for her at the hotel. He would take away her daughter, and she wouldn’t see her again. How could she have lied to him?

She knew her husband well enough to know that those messages were only threats. He needed that whole performance—the wronged man, the repentant woman—just as much as she needed to occasionally escape from home. Besides, he was very prudent and put appearances above all. He would be incapable of making a fuss that the neighbors would overhear. Nonetheless, sitting on that hard bed, watching the devouring flames, she entertained for an instant the image of her husband bursting into the room.

She imagined the disgust on his face at having to pass, in the middle of the night, through streets inhabited by terrifying creatures, and she pictured the very white light at the front desk highlighting the acne marks on his cheeks. She saw him abusing the hand sanitizer in the reception area, anxious to armor himself against the ugliness of that cheap hotel.

She saw quite clearly the image of her husband entering the room in his disheveled pajamas, horrified, watching her lick her blood- and viscera-smeared lips. He would find her naked, examining the young man’s inert body, sniffing and fondling it, eager to enjoy its best parts. Her mouth would be red, very red and very bright, and only that brightness, her savage hunger, would be capable of illuminating her husband’s pale face. An explosion. Then another. She desired that scene, burned for it. She needed to see some genuine expression in the face of the man with whom she’d shared a bed for so many years.

But all she found was blackness.

And then the red and the orange.

The flames, still consuming everything on the screen, now bounced off the vacant stare of that man who observed her without even a glimpse of horror. Without allowing himself to burn. Controlling himself so that not a shout would escape him. So that nothing would alarm the neighbors.

Joel Streicker’s stories have been published in a number of journals, including Great Lakes Review, Gravel, Burningword, and New Flash Fiction Review. He won Cutthroat Magazine‘s Rick DeMarinis Short Story Contest in 2021 and Blood Orange Review’s inaugural fiction contest in 2020. He has published poetry in both English and Spanish, including the collection El amor en los tiempos de Belisario. His translations of such Latin American writers as Samanta Schweblin, Mariana Enríquez, and Pilar Quintana have appeared in A Public Space, McSweeney’s, and other journals. Streicker’s essays have appeared or are forthcoming in The Forward, Shofar, Le Monde diplomatique, edición chilena, Boletín cultural y bibliográfico, El Malpensante, and Letralia, among other publications. Photo Credit: Paul Asper

TWO POEMS by Kuhu Joshi

Saraswati on a Sunday morning

All this living alone. This mug

With my initials on it, scrubbed

And put to dry

On the kitchen slab. It waits for me.

Looks happiest when filled up.

I’m a bit sick of Maria – my

Areca palm

There by the bookshelf. She

Dances. When it gets like this I

Don’t know what to do with myself.

Fridge then bed then a book.

Laundry helps. I end up feeling useful.

Now when Brahma comes

I let him. More new books?

He always picks one off the shelf.

On good days

He reads the blurb and

Sits down. Otherwise it’s the bed straight.

Highlights of a cricket match

On his cell phone. Come

Let’s listen to a song.

I want to sleep.

Evening

How can I describe what I’m unable to praise?

The birds are chirping in the low berry bush.

I don’t know who they are, they don’t know my name. An ambulance,

a siren, the emergency ward I’ve have identified just in case,

sitting at a marbled coffee table, marigolds in a vase. Green, leafy,

dying. God – I like to pretend you’re watching.

In this case, you are a man. It makes sense – I’m lonely.

The earth is not speaking back. The baby cries

in its pram. The mother rocks the pram, hushing,

making her teeth large and shiny. The father smiles at me.

On the bridge, people are carried

in the body of a train, nodding like peonies.

SELF-PORTRAIT AS THE CORNFIELDS by Carolina Hotchandani

| I am a citizen of a former British colony that rebelled from England with a great tea party, declaring itself its motherland one day. America. Was it orphaned? Did it kill its own mother? Poor England. Where are you from? the other Americans ask me. My mother is Brazilian; my father is Indian. I was born in Brazil, but I’ve been here a long while. Here where? Here here. Here, New York, Texas, North Carolina, Tennessee, Rhode Island, a year abroad in England, then California, Iowa, Texas again, then a year in South Korea, then Chicago, then another “South,” but this time South Dakota, which isn’t in this country’s South at all. Now Nebraska. Here here, where the cornfields stretch from the highway to the horizon. Here here, where corn is fed to cattle who don’t graze. Hear, hear! as they shout in the House of Commons, to affirm the speaker’s thoughts. Hear, hear! to the English that seems foreign. Hear, hear! to the rustle of corn that doesn’t belong here. Hear, hear! to the language I use to build this block of words, which you may not hear at all, if you are quiet, if you follow the lines with your eyes, unspeaking, like mine, as they trace the rows of corn in the fields. Fed to the cows that Indians know as holy. Fed to the cows the Americans know as beef. I will become your cornfields, striped, farmed, not native at all, but everywhere, everywhere. |

TWO POEMS by Daniele Pantano

CORRUPTED (WASTEWATER)

We ask to be made too

. . .

short and bleeding to be

. . .

strangled with candy floss

. . .

to taste what it takes

. . .

to reach another to be absolutely

. . .

nothing but spoken about

. . .

to spell innocence or renewal

. . .

to know it’s always been there

. . .

that time is short and to expect nothing

. . .

to say how the window is a stranger

. . .

once more to know that the end

. . .

of water is a flood.

THE POET’S POET (WRITING & REWRITING THE FINAL LINE)

Every blanket’s worth a voice. In the end.

. . .

The bandages suggest torture. Or execution.

. . .

The ambition to grasp the totality of existence.

. . .

The lies of despair and consolidation. The sublime.

. . .

The harvest view you’re so ashamed of. Clouds.

. . .

The desolation above you. Nothing else.

. . .

The child walks by a mirror tired of being one of many.

. . .

The diaphanous wax and pigments. Speech.

. . .

The mark of an individual – an ambitious solo.

. . .

You never see the grass crawl near the flames.

TWO POEMS by Lucas Jorgensen

The Bureau of Consumption

It’s the warmest day of the year so far in Brooklyn, where I confess I have done a bad thing quietly. The self-storage center, a jolly roger, glints with a novel kind of light. Last night, I had a green potato and didn’t die. Today, I had another. Off the R near Red Hook, Brooklyn looks like Cleveland: pre-war warehouses, overpasses, russet brick and beige concrete. Past the playground I once pissed in, drunk, locked out of my apartment, my calves ache from jumping jacks, I’m unable to hold my whole weight when I plank. The questions are, as always, who benefits? Am I diabetic? I’m in the best shape of my life.

Last summer I was mad, I picked a direction. A young boy asked if I was a believer, then blessed me anyway. It’s different now. Sixty degrees. In Florida, I’d wear sandals into frost, tell people I’m from Ohio. A man on a yellow quad bike comes up my strip of sidewalk, almost runs me over, then another, blue. A man with a broom clears debris off the street a few feet from a pile of water bottles. When I come back tomorrow, the block will look too clean.

Two young boys fight by a hand-painted NO PARKING sign. I do not intervene. Like a castle on the corner looms a KFC. For a moment I wonder what it’s like to eat ostrich meat. I hear my knee click and ponder how I believe in anything. If I order a bucket of fried chicken from the takeout window, the Magritte painting in my head—ham steak, eyeball stuck like an olive in its center—would be the only witness. “No one would stop an ordinary act of cruelty,” the wind says, whistling off barbed wire. What an absurd man you are. If you wanted to be less outraged, you should have been born in less outrageous times.

The Bureau of Nature

Single file, we put the pigs in pens. Each pig an exact copy of the last. Exact plumpness of snout and jowl and flank. Tender and marbled in an exact and scientific way. Each morning, the pigs squealed one time in unison, and the first morning, we were startled awake. But we were so comfortable. And it was just another alarm left on in another apartment. And we were so comfortable—to go back to sleep, to ignore it. When the pigs grew large enough, a large man came out with a large gun, and held the gun up to the first pig. One pig fell, and each other collapsed—the shared dream of mud and apricots spilling from each pig’s head.

INVITATION TO END by Faris Kuseyri trans. Patrick Sykes

A woman puts an orange in her husband’s pocket

and her longing I saw

they’re opening unmarked graves with warrants

and silence’s strength I saw

truth bound, the papers lie

and hate in the words I saw

grace in the bazaar, conscience in exile

and the feigned surprise I saw

driven again to my pencil’s mercy

and the invitation to end I saw

from poison mouths the children kissing the vine

and their glass bravery I saw

Patrick Sykes is a journalist and writer based in Istanbul, Turkey.

- Published in ISSUE 27, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Anne Vegter trans. Astrid Alben

With permission from the publisher

WILDCARD

A light-hearted lullaby this, not much happens

that doesn’t already happen somewhere else:

a garnet-red baby opens wide its tiny jungle mouth.

Familiar to all who read them, lullabies are

about kisses, jealousies and parents / keepers.

Raging in the pillow, rising like a statue made of ash.

A parent is a house. Gooey goo-goo. Food, milk,

lalala. A lullaby disentangles love.

Be joyous and light touch. Filter light,

the air is of an invaluable purity.

Compared to wellbeing I daresay it’s cloud-cuckoo.

Parents / moods / components of the growth machine:

baby’s first, baby’s own, baby’s living it up. Joyous,

carefree bellowing in a sun-drenched nursery. Done.

Hearts plead, hearts steam: Adonai —

give me back my stalemates, my singular days, my intact membranes.

ISLAND MOUNTAIN GLACIER, PART IV

Even when I, in this minute of my kingdom, in this household of seasons (jan steen), in this

temple (breath), leave it all to you (here sweetie, for you) I elevate your thin meat to a spectacle.

Even when I touch the memory of your hips, your hands tiger my uh-huh parts

ingest me (tongue chest lips) and I read my gape from your lips or should that be gave.

Selections from the Appendix

Appendix

Just like a poem, a translation emerges out of its own possibilities. It is built up of layers, alternate states that enter the work and flow through it. Options, possibilities, stabs, trials and errors, interpretations and choices are made, discarded, brought back, revived, knocked about, improved and transformed.

I got to dissect and study Anne Vegter’s craft as I worked on these translations of her poems. This was a gift. More than a reader, a translator becomes the work’s mechanic. I dismantled each poem, uncovered its particulars, brilliance, magical flurries, flaws, oddities and the syntactical, semantic, sonic, rhythmic bones and muscles that hold it together. On my desk, the poems to be pulled apart, experimented on and reassembled in the new language. Like twins wearing different outfits and sporting different hairstyles, the original and the translation are intimately related yet distinctly separate entities.

Translations are like poems, a work in progress. It is nothing more complicated than that. And then, of course, it is. This appendix shares my process, isolating my choices and keeping the layers of possibility visible for the reader to create their own arrangements and, where necessary, to improve the translations. For I am but one of what I expect will be many more translators bringing Vegter’s writing to an English readership.

Astrid Alben, 2021

TRAMPS

You spoke of an emotional chill, below zero you said it was between

my thighs in the departure lounge. After your bag we hugged heart to heart,

I could’ve joyfully sucked you off. Are you even listening?

We resembled wiry birds; you designed a deathblow on paper,

had yourself a little after-fun with your boredom. It got tricky finding reasons that way.

When the glass slips from your fingers you go find a cure for cracks and salt.

The carpet grins. Will finally someone stand the fuck up and hold me?

TRAMPS

You talked about air temperature, below zero between my legs you said in the

departure lounge. After your bag we hugged each other coeur à coeur,

man I could have blown you I was so happy. Are you still listening.

We reproduced rigid birds, a deathblow’s what you designed on paper

had a little after-fun with your boredom. It became tricky to find reasons that way.

When the glass jolts / jumps / leaps from your finger you look for a cure / remedy against cracks and salt.

The carpet grins. Will finally someone stand the fuck up and hold me.

VAGABONDS

You talked about instinct-heat / emotion-temperature, you found it below zero in the

departure lounge. After your bag we hugged each other coeur à coeur,

happy as a lark ready to blow you. Are you still listening.

We faked / forged / imitated rigid birds, you designed a deathblow / deathly fall on paper

had some after-fun with your boredom. It became tricky to find reasons [in] this way / method / manner.

If the glass leaps from your finger you look for something / a cure against cracks and salt.

The carpet / rug / runner smirks. Will someone stand the fuck up and hold me.

Astrid Alben is a poet, editor and translator. Her most recent collection is Plainspeak (Prototype, 2019) and Little Dead Rabbit (Prototype, 2022).

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation