SEPTEMBER MONTHLY: Interview with Jessica E. Johnson

We’re excited to share a new series of interviews exploring craft. In these conversations, we’ve asked writers to take us behind the scenes of their finished works, showing us the process behind the poem, the scene, and the story.

First is our conversation with Jessica E. Johnson, on her memoir Mettlework: A Mining Daughter on Making Home. This memoir explores her unusual childhood during the 1970s and ’80s, when she grew up in mountain west mining camps and ghost towns, in places without running water or companions. These recollections are interwoven with the story of her transition to parenthood in post-recession Portland, Oregon. In Mettlework, Johnson digs through her mother’s keepsakes, the histories of places her family passed through, the language of geology and a mother manual from the early twentieth century to uncover and examine the misogyny and disconnection that characterized her childhood world– a world linked to the present.

Considering the focus of these conversations is on process, we’d be remiss to overlook our own process in conducting the interview! We’d like to give special recognition and thanks to our 2024 summer intern, Kirby Wilson, who helped shepherd these conversations from initial readings to their final form. Kirby was instrumental in crafting the conversations you now see before you.

Enjoy!

- Published in home, Interview, Nonfiction, Video

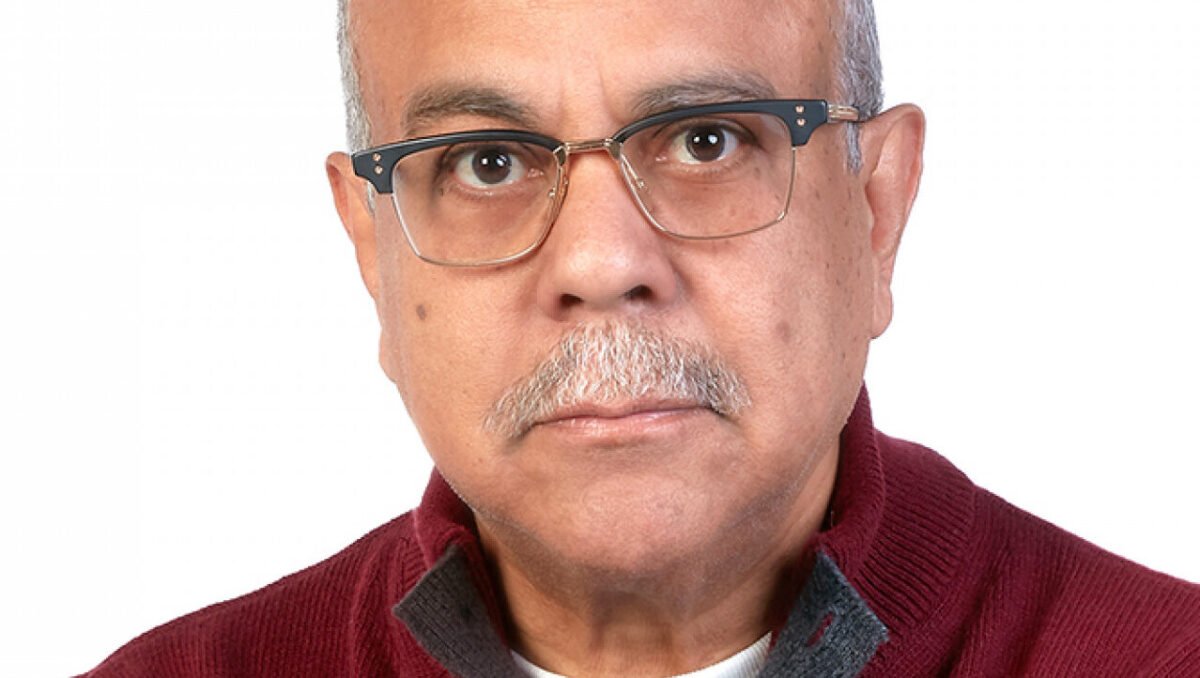

URGENT: NEWS OF THE DEATH OF HIBA ABU NADA by João Melo, trans. G. Holleran

Excuse my urgency, oh right-thinking beings

especially you translucent

and self-referential poets,

but one of our sisters,

the Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada,

has just died in Gaza under the shrapnel of a benevolent bomb,

sent by another God,

different from the one she spoke with

every day.

I hesitated to convey this fateful news

so hastily. Perhaps I should wait

for the leaden grey smoke from the bomb that killed her to dissipate,

while she, surely,

scrutinized the sky for a sliver of light and

maybe even

the last birds.

Or, more convenient yet

it’d be better to say nothing,

until today’s hegemonic oracles,

like all oracles,

circulate an official statement

denying it as usual

without any doubts

or uncomfortable questions.

But when I read

the last words of Hiba Abu Nada before she died,

I was moved to spread this news,

before her banner could be censored

by those who defend selective liberty:

“If we die, know that we are content and steadfast,

and convey on our behalf that we are people of truth!”

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Poetry, Translation

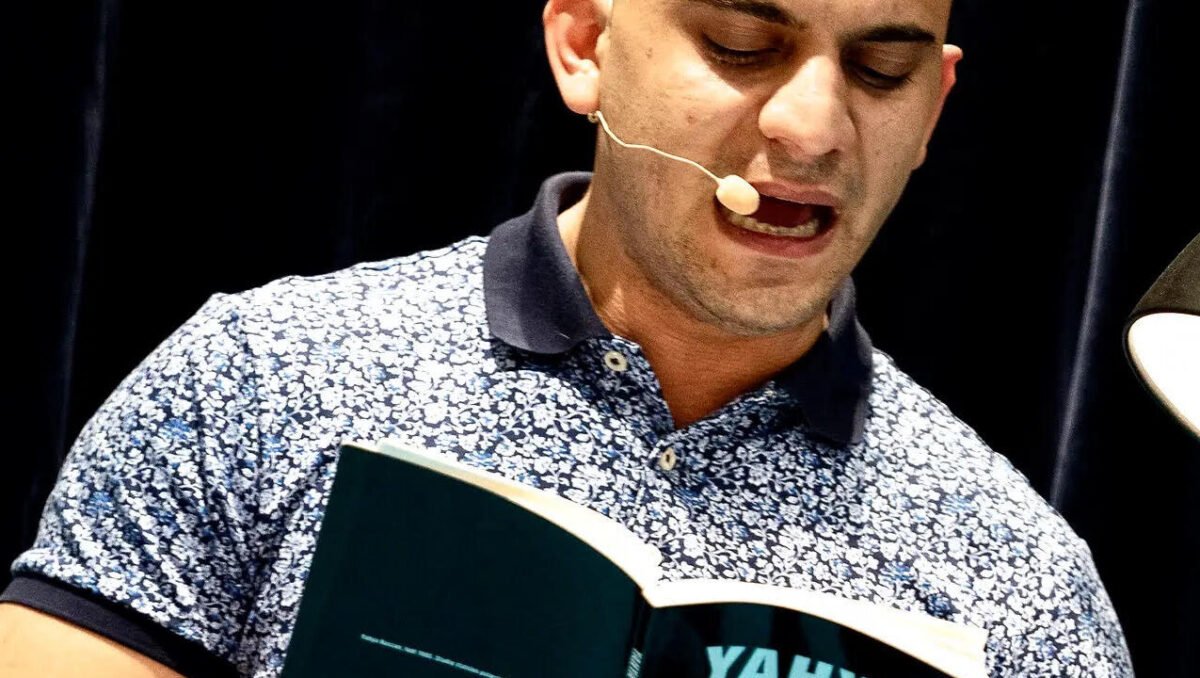

FOUR POEMS by Olivia Elias, trans. Jérémy Victor Robert

Day 21, Words Are Too Poor, October 28, 2023

words are too poor but I have only them

my only wealth

empty my hands & so great the sufferings

here again I press my arms around my chest

here again I get into this old habit of covering the page with little

squares filled with black ink

the little squares of our erasure

/

I write what I see said Etel Adnan* who knew a lot about

mountains’ strength as well as Catastrophe

I also know the power of this Mount facing the sea

Carmel of my very early days Mount Fuji of absence

& denial around which I gravitate above it the

black crows of desolation

as I know all about our Apocalypse which keeps on repeating

repeating the earth turning on its axis the sun that veils its face

/

here’s what I see

the madness of the overarmed Occupying State

crushing bodies & souls live on screens at least until

night falls a night of the end of the world only

pierced by ballistic flashes

in Sabra & Shatila the spotlights

. illuminated the massacre’s scene

today in this Mediterranean Strip of sand

. total darkness shields Horror

the sky explodes in a thousand pieces amongst

monstrous mushrooms of black smoke the time to

count one two three towers collapse one

after the other like bowling pins their inhabitants

inside then get into action the steel monsters

flattening the landscape they call it

(translation: converting this ghetto sealed off on all sides

into a 21st-century Ground Zero)

everyone wondering When will my time come?

& parents writing their children’s name on their small wrists

for identification (just in case)

/

no water no food no fuel & electricity & no medicine

decided the Annexationist Government’s Chief

let’s finish this once & for all & forever they shout

relying on the unconditional support of

their powerful Allies the ones primarily responsible

for our fate by writing it off on the bloody chessboard

of their best interests

as if their contribution to our erasure redeemed their crimes

Hear Ye Hear Ye

proclaims America’s great Chief, waving his veto-rattle

Absolute safety for the Conquerors

Hear Ye Hear Ye

chorus the mighty Allies

/

Gaza / 400 square kilometers/not a single safe place /2.3 million people /half of them children / hungry /thirsty/injured /desperately searching for missing family members dying under the rubble

& Death the big winner

/

they should know that souls cannot

be imprisoned no matter how tight the rope

around the neck & how strong

the acid rains & firestorms

One day, however, one day will come the color of orange/

/a day like a bird on the highest branch**

where we will sit

in the place left empty

in our name

in the great human House

————

*Etel Adnan, “I write what I see,” in Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito: Post-Apollo Press, 1986; Brooklyn: Litmus Press, 2021).

**“One Day, However, One Day,” from Louis Aragon’s homage in Le Fou d’Elsa (1963) to Federico García Lorca, who was murdered, in August 1936, by Franco’s militias.

DAY 74, THERE WILL ALWAYS BE POETS, December 20, 2023

instability a general rule

it seems a new ocean’s on the verge

of emerging in

Africa

& floating between

here

&

there

could affect not only people or land

but also the seasons I experienced it

of fall I didn’t see a single thing

this year the acacia’s

color even changed without

my noticing

one morning looking through

the window I realized

it was there

naked

at its feet a carpet of yellow

leaves littered the ground

nothing to keep it warm

exposed

to the cold icy rain missiles

& here I was & still I am

glued to the screen

startled by every explosion

of the red-little-ball

clinging to the glittering

garlands

as soon as one of the

flesh-eating-red-balls hits

the ground a sheaf of fire

bursts followed

by a huge black smoke

cloud

then

screams

cries

panic

agony

day & night (even

more so at night) keeps on

going the hypnotic

ballet

today

Day 74

74 days of this

will spring come back

or only a long winter

of ignominy cold hunger

history will remember

there will always be poets

to tell the martyrdom

of the Ghetto People

NOTE: An earlier version of this translation appeared on 128 Lit website, December 28, 2023.

HEAR YE, HEAR YE!

At regular intervals shaking his rattle carved with the word veto the Grand Chief of America takes the floor for an urbi et orbi statement

With the utmost firmness

broadcast on a loop

in newspapers on screens

around the world

withwithwithwithwithwithwith

thethethethethethethe

utmostutmostutmostutmostutmost

utmostutmost

FIR/MNESS

like

FER/OCITY

growing

exponentially

utmostutmostutmostutmosT

exceptionallyFirm

FIR/MNESS

FIRE/MESS

Iron balls blazing

in the sky

black & read whirls

it’s raining

black ashes

east bank not west

with the utmost

firmness

We support the Conquerors’

Right to Security

COLIN POWELL. GUERNICA. SCULPTURE

1

The devil is in the detail. Colin Powell–former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of State to the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush, between 2001 and 2005–was said to have placed great importance on this. Unfortunately for him and the legacy he leaves to history, he broke that rule on one memorable occasion

It was on February 5, 2003, when he called for a military crusade against Iraq on the podium of the United Nations, based on false evidence of weapons of mass destruction. His effort resulted in the very thing it was supposed to prevent–the deaths of hundreds/hundreds of thousands of Iraqis–& plunged the country into widespread chaos, which is still unfolding today

That day, UN officials covered with a blue veil a tapestry hanging at the entrance of the Security Council representing Guernica, the monumental work painted by Picasso at the request of the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War. Twenty-seven square meters commemorating the stormy & total destruction of the small town of the same name by the German & Italian air force, on April 26, 1937

2

In March 2021, the tapestry was returned to the Rockefeller family who had loaned it for 35 years & wanted it back. Has it been replaced? With what work? I don’t know, but I’ve got an idea. Let’s offer a cubist sculpture/assemblage of 550 stones extracted from our lands on which Settlers, protected by militias/soldiers & courts, are having a great time

Upon each of these stones

that capture the light so

beautifully

is an inscription: the name of

a village

from yesterday and today

that was

razed/ablaze

May a blue veil cover it when the Guardians of the ghetto & the bantustans take the floor

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

- Published in Poetry, Translation

INTERVIEW with ROBIN LAMER RAHIJA

Robin LaMer Rahija‘s first full length collection, Inside Out Egg, was released in April. Ada Limón writes that “each poem contains the whole unbound strangeness of the human experience–the offhand remark, the blur of being in a body– all of this is written with a humility and understated wit that both growls and sings….” We were thrilled to interview Rahija about her process in crafting Inside Out Egg, as well as the development of this collection’s voice and the nature of the absurd– both in poetry and in the world around us.

FWR: Your poems conduct us into a theater of the absurd where you satirize our fears, our peculiar tendencies and our most ridiculous but touching attitudes. Your voice rings with audacity, and performance, as well as rebellion. When you say, “Something just feels wrong”— about our culture, our lives today, our attempts to find each other, the reader believes you. But, the tender, humorous way your poems express both the wrong and the small touches of “right” give us, your readers, both pleasure and hope in finding community.

I’m fascinated by the short poems that you’ve interspersed in your text that raise mind-boggling questions like “who’s to blame for this bad dream” and comment on the many uses of the preposition “for.” Did you conceive of them as breaks or respites, or did you have other thoughts about their place and placement in your book?

RR: Do you mean the Breaking News poems? The Breaking News poems I thought of as interruptions, like when we’re having a meaningful interaction with someone and the news app on the phone pings with something insignificant, or significant and horrifying, or stressful, and then the moment is gone. I wanted them heavy in the beginning and then to fade away as the book sort of settles into itself and the voice becomes more focused.

FWR: I think many writers and readers, including me, are interested in questions of process. Would you tell us a bit about your process—how a poem begins for you, if there are recognizable triggers; how you develop that initial impulse; how you revise, and so on.

RR: I think about this a lot. It might be different for every poet. It seems like magic every time it happens. Often it’s phonic. I’ll hear a phrase that sounds cool, and it will get stuck in my head like a song lyric. A friend of my told me a story about seeing a fox on the tarmac as they got on a plane, and I’ve been trying to work the phrase “tarmac fox” into a poem ever since. Other times it’s more about just noticing language doing something weird. I was watching the Derby the other day and a list of the horse names came up, which are always ridiculous: Mystik Dan, Catching Freedom, Domestic Product, Society Man. So now I’m thinking about a list poem of fake horse names, or what they’d name themselves, or what they’d name their humans if they raced humans for fun. The trick is training yourself to notice those moments, and also to note them down and not just ignore them.

FWR: Also, to my ear, you have a very strong, confident, even outspoken voice in your poems. One example that caught my ear is your title, “I Can Never Put a Bird in a Poem Because My Name is Robin” and “That Is Not Fair That” voice, to my ear, is quite brave, as well as funny. How did you develop that voice, or was it always natural to you?

RR: No, it’s definitely not my nature. I had to write my way into this voice. I started out writing language poetry that was just pretty sounds with no meaning. I was avoiding writing (and thinking about) the hard things. Writing for me has been a lot of chipping away at my own walls. Each poem too I think has to work on becoming that confident through revision. I don’t want my poems to be complaints. I want them to reveal something, but it can be a fine line. I’m a jangly bag of anxiety most of the time, and I think my poems reflect that. Writing is an attempt to make the jangles into more of a coherent song.

The humor is mostly accidental, I think. Or maybe it comes from an inability to take myself seriously. I do want to get the full range of human emotions out of poetry, and humor is a big part of how we get through the day.

FWR: Who are you reading now? And are the poets you read representative of anything you would describe as “contemporary”? Is there such a thing now? I’m thinking of Stephanie Burt’s essay describing recent poetry as “elliptical,“ meaning the poems depend on “[f]ragmentation, jumpiness, audacity; performance, grammatical oddity; rebellion, voice, some measure of closure.” Does any of this ring bells for you?

RR: I haven’t read that but it feels true for my work. I’m reading Indeterminate Inflorescence by Lee Seong-bok from Sublunary Editions right now. It’s a great collection of small snippets, like poetry aphorisms, that his students collected from his classes. I don’t know how I’d describe contemporary poetry, except it feels brutally personal and outwardly social at the same time.

NEVER ENOUGH by Dustin M. Hoffman

April worked Hector’s hair into pigtail braids. “I fucking love you,” she said and then hated herself for sounding cheesy as bullshit TV, like burnt sugar on her tongue. She’d unplug every TV, yank a million miles of cable wires, just so she could be the only one saying stupid things.

She finished the second braid and told him to take off her underwear. She bit his neck. His sweat tasted metallic, tasted like a fizzed-out sparkler stick. She tugged his hair, wanted to fuck as hard as hating her town called Alma, as hard as hating her parents and their house served with eviction and this winter and this world.

“Someone’s watching,” Hector whispered.

Behind her, some horror was playing out: Her father waving a claw hammer. Or it was her mom, who could do nothing but gawk and worry. The queen of the crumbling castle.

April pulled on her jeans. Outside the door she’d left cracked, slippers shuffled against linoleum.

“That fucking weirdo.” She pulled an inside-out Suicidal Tendencies T-shirt over her head. “She just stood there watching.”

“What should she have done? You want her to yell? Or, what, slap you?”

“Yes,” April said. “Fuck yes. That would be doing something at least.” She felt her face reddening down to the freckles on her chest.

“She’s losing her home, too,” Hector said.

“Why are you taking her side?”

She sat on the edge of her bed, back to him. She wished he’d tuck her body against his again, but not fucking this time, just staying close.

The bedroom door swung all the way open. April’s little sister tromped into the room. She wore royal blue gym shorts and a white tank top. Her hands were wrapped in fingerless red-leather fighting gloves, and she had a shovel slung over each shoulder.

“Mom says you need to help.”

“Jesus, Elise. Know how to knock?” April passed Hector his underwear. “How about everyone just comes into my room to stare.”

“She says I gotta dig, and I said, bitch, if I gotta dig so does April and her screw buddy.” Elise’s leather knuckles pushed a shovel at April.

“Why aren’t you in school?” April asked.

“School’s been over for like an hour,” Elise said. “Where were you?”

“I’m done with that place. What’s the point?” She’d skipped the last three days, and she might never go back.

“Is that Hector?” Elise’s shovel tracked down his neck to hover over his heart like an accusation.

“Who the hell else would it be?” April said.

“I’ve never met this dude. How do I know?”

April snagged the shovel out of her sister’s hand. “No one meets anyone around here. Might as well hide from the world like Mom.”

“Not me. I’m taking shotput all the way to a freeride from some sucker college. Then I’m going to fight as many bitches as I can knock out until UFC starts up a league just for me.”

“You’re a moron if you think anyone’s going to give you anything for free,” April said.

“Maybe UFC will broadcast me kicking my sister’s ass.” Elise shadow-boxed jabs at April’s stomach. She finished with a fake palm-heel aimed at her nose. April didn’t flinch. She rolled her eyes and drove a shovel spade into her bedroom floor, chipped it because it meant nothing, because soon some other assholes would own it and now, they’d own this scar too.

*

Outside, April watched Hector and Elise foolishly pang shovels against frozen dirt. Elise stabbed with rhythmic violence. This was just another workout for her. Hector hopped on his shovel and struggled to unearth more than a frozen shaving. No one had any idea where to dig. For years, their mother had buried cash. She’d slip slim rolls of tens and twenties from Dad’s wallet and into Campbell’s Soup cans and empty shampoo bottles. Then she’d bury them in the backyard. Dad used to laugh about it, told them it made Mom feel safe. Besides, Dad would say, we have plenty of money so long as houses need painting and I have hands to swing a brush. That had been true in the fat summers, when just enough paint peeled off rich people’s siding to pay the bills.

“Why isn’t Dad helping?” April asked.

“Gone-zo.” Elise shovel-stabbed the earth. “He’s working.”

Their house was sided in vinyl. April’s dad installed it himself, was proud his own house would never need paint. Her dad had bought this riverfront one-story after the flood of ’86. They couldn’t have afforded it if the basement hadn’t filled with water and mold. Dad installed a sump pump in the basement and, at the age of five, April had helped tear the moldy walls down to studs. Gutted and born again perfect, he liked to brag. This was their house. Except it wasn’t anymore.

“It won’t be enough to stop anything,” April said. “Neither will this.”

Elise’s shovel clinked and she dropped to claw out a rock. She rolled onto her back and chucked the rock at the iced-over river, then did twenty push-ups before she resumed digging.

After a few minutes of digging ice, April gave up. She tried to remember watching her mom dig in those summers before she stopped leaving the house altogether. Through the window, she’d be wearing hideous gingham dresses she sewed herself. The ankle-length skirt would be crusted in mud, her pits sweat darkened. She’d wave at her daughters spying through the window, the setting sun and river twinkling at her back. She was beautiful, sure, but beautiful didn’t stop her from getting crazier.

April javelin-threw the shovel back toward the house, where her mom now watched from the window’s yellow kitchen light. April hoped she hated herself for burying all that money. She hoped she felt like dirt for not helping, for being helpless. She was probably thinking about the move, trying to calculate how she could seal herself inside a cardboard box so she wouldn’t have to encounter the outside world. Locked in a box would never be April’s way.

Hector was still at the same spot, still digging straight down when April touched his shoulder. “Let’s get out of here before you hit a gas line.”

“I think I’ve almost found something,” he said.

“Let’s go far away, somewhere no one we know has ever been.”

“Almost there. See.” Hector’s shovel spade dredged up tiny crumbles. There was nothing to see.

“Let’s steal my dad’s truck, then fuck and drink and do whatever we want without anyone watching.”

“Or we could stay.” Hector chuffed steam breath.

“He find something?” Elise pirouetted into more shadowboxing aimed at Hector’s sunset-stretched shadow.

“Almost,” Hector said. They both stared into the nothing hole.

“Let’s go.” April tugged Hector’s jean jacket. The sun was almost down, but they could still ride into it and turn into balls of fire.

“Quit nagging him, bitch,” Elise said.

“Quit encouraging this ridiculous shit.”

“Quit bitching about every little bitch thing.”

April slid her leg behind Elise and dropped her. Elise popped back up and tried for a headlock. Then they were both on the ground, and April felt how small her tough-as-nails little sister was. Elise didn’t understand how she couldn’t win this fight, how they wouldn’t find Mom’s money, how their home was already gone. Elise was making muscles and dreaming big and half of April wanted to punch all the hope out of her twerp face and the other half wanted to hug her so close.

“There we go.” Hector dropped to his knees, reached bicep-deep into his hole. April expected another rock, but Hector lifted a can of tomato soup. He held it up against the last sunlight. It was poisonous hope. If they dug all through the night, they wouldn’t find another. Elise counted out each of the thirty-six dollars with a yell that sailed across the river. Hector and Elise clinked shovel spades together, and then Elise ran the can into the house.

“I told you I’d find something.”

“Stupid luck,” April said.

“We can go now.” Hector was beaming. “I won.”

“My fucking hero.” She smiled too. But she was becoming as frozen as the ground, every petty treasure buried and irretrievable.

He jogged into her house, didn’t even notice she stayed outside to kick dirt into Hector’s hole, patching up the lawn nice for whoever would own the house next.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Fiction, home

AN ENGINE FOR UNDERSTANDING: AN INTERVIEW WITH Willie Lin

Willie Lin’s debut poetry collection, Conversations Among Stones, will be published in November 2023 by BOA Editions. Simone Menard-Irvine interviewed Lin for Four Way Review.

FWR: I would like to start out by first asking about what it’s like to be publishing your first full collection of poetry? What was the process of writing and assembling like in comparison to the publication of your earlier chapbooks?

WL: My urge in assembling manuscripts is always to pare down. Because of this impulse, assembling my chapbooks felt like a much clearer and more straightforward process. For the manuscript that became Conversation Among Stones, I struggled with holding it in its entirety in my mind and had to be more deliberate in my approach. I understood how certain constellations of poems fit together but was a bit overwhelmed with shaping the manuscript as a whole. At one point, I actually made a spreadsheet of all the poems that I thought might belong in the book and notated and ordered them according to a few different axes to help me see how they might fit together.

FWR: Your title, “Conversation Among Stones” brings up questions of action between the inanimate. What inspired you to frame your collection under this title?

WL: That idea is definitely part of what I had hoped to evoke with the title—of speaking to the inanimate and what can’t or refuses to speak back, of language spanning, filling, straining, or distending across gaps, of failing to say or hear what matters. I think these intimations are a good way of entering the book, which I hope worries and enacts some of these concerns regarding the capacities and limitations of language.

FWR: My next question is in regards to the variations of length in the poems. In “Dear,” which is only two lines, you write “A knife pares to learn what is flesh. / What is flesh.” Both a statement and a question, you ask the reader to consider something so simple, yet laden with ideas regarding the body and violence. What was your process in developing these shorter pieces, and how do you see them functioning within the broader collection?

WL: Poems can beguile in so many ways, but I’ve always loved the compactness of a short poem. Part of it is how easy it is to carry them with you in their entirety and turn them over in your mind. Since I first came across Issa’s “This world of dew / is a world of dew. / And yet… and yet…” in a poetry class almost 20 years ago, I’ve been able to carry it with me. I’ve learned and forgotten countless things in poems and in life in the ensuing years, but have kept that poem almost unconsciously, without effort. Another aspect of short poems’ appeal to me is the paradoxical way time works in them. A short poem’s effect feels almost instantaneous because of its brevity but time also dilates across its lines. The duration seems somehow mismatched with the time it takes to run your eyes along the text. In Lucille Clifton’s “why some people be mad at me sometimes,” the body of the poem answers the charge of the title in five short lines:

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine

That last one-word, monosyllabic line, especially, seems to take forever to conclude. The compression of the poem—the words under pressure from the wide sweep of white space—exerts a redoubled, outward pressure and reverberates.

My poem “Dear” started as a longer poem (not longer by much, maybe 10 lines or so). At one point, as an experiment, I took out all the “I” statements in the poem and arrived at the version that exists now. Often, that’s how it works. I try different approaches and revise, sometimes rashly and foolishly, until something jostles loose. When I finally got to the two-line version of “Dear,” for me, the fragmentary nature of it fit with the precarity of its assertion and question. How the shorter poems appear on the page also matters in that I wanted the blank expanse that follows the poem to function as an extended breath. Because the book proceeds with no section breaks, it made sense to me to vary the lengths and movements of the poems to establish a kind of cadence, a push-and-pull.

FWR: In thinking about the themes that circulate throughout your work, a couple of specific ideas stand out as particularly potent. One is the issue of memory; the violence, complexities, and confusion of your past run their threads throughout the collection. In “The Vocation,” you write, “In the year I learned / to cease writing about history / in the present tense, / I was the silence of chalk dust, / of brothers.”

It seems like history, for the speaker, is something to be dealt with, instead of accepted unquestioningly. What does writing about the past, be it in present tense or not, do for you as an individual? Does confronting the past through writing work as a catharsis, a way to process, or does it instead serve as a conduit to expanding upon the ideas you wish to convey?

WL: I think memory—and the process of remembering—is an engine for understanding and, by extension, meaning. For experience to make sense, we have to remember. Knowing or thinking can’t really be separated from experience. It’s also true that memory, personal and communal, is restless and malleable. I have an image of the past as a landscape of sand dunes. The shapes drift. They slip, they resettle. How things feel in the moment can be one kind of understanding, how we remember them, how they shift, linger, rise, how they appear in the context of things that have happened since or what we do not yet know are other kinds.

In Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay,” when challenged on why she remembers “too much”—“Why hold onto all that?”—the speaker responds, “Where can I put it down?” I suppose poetry for me is one place to put it down. (Though I don’t think I could be accused of remembering too much in life. I have a terrible memory.) In writing a poem, I’m making a deliberate attempt toward an understanding, however provisional. Poems are good spaces for holding and turning, for thinking through and imagining, for venturing out—and that is the final, extravagant goal, to reach out and connect with someone else. In my poems, I want to make a path that leads inward to the center—and out.

FWR: In that same poem, you confront another central theme: men. When you mention men, they are typically described via their participation in fatherhood or brotherhood. You write, “the men/slammed the table when they laughed/at their circumstance, or drank/too much to learn what it meant/to have a brother, or were true to/no end, or tried to love their fathers/before they disappeared into/hagiography.”

Masculinity here seems to be defined as a relational identity, one that is constituted by lineage and socialization. I would love to hear you speak on your relationship with gender norms and roles, especially in your writing.

WL: This question is particularly fascinating because I can’t say I conceived of my poems working together in this way, even though of course you’re right to point to how often these types of familial terms come up. I suppose part of the answer has to be how the poems relate to my autobiography. In my family, my mother is the only woman in her generation. She has two brothers and my father has two brothers. I’m also the only woman in my generation. I have three cousins, all men. I’m an only child who grew up in China during the one-child policy, so all around me were lots of children just like me, who’ll never know what it means to have a sibling. I felt a bit of an outsider’s fascination with those types of relationships and inheritances, especially as I got older and became more aware of the other social forces at work that historically favored sons. I think poetry can function partly as personal interventions in cultural history and memory, holding the ambivalences, contradictions, and idiosyncrasies that live at those intersections.

FWR: We see many instances of place in relation to memory, but there are only a few instances in which those locations are given a specific name, such as in “Teleology” when you mention Nebraska. Can you walk us through your approach to location in your work and what places need an identifier, versus places that can exist more specifically within the speaker’s domain of recollection?

WL: I think generally the idea of dislocation is more important than the locations themselves in terms of how they function in the poems. Saying the name of a place evinces a kind of ownership of or intimacy with that place. For many of the poems, in not naming specific locations, I more so wanted to evoke a sense of rootlessness and for the intimacy to be with the speaker’s uneasiness within or distance from those places. “Nebraska” in “Teleology” is a departure from that model not only because it offers a specific name but also because I think in this instance Nebraska is not a real place but an imagined one—a kind of projection that stands in for other things (the poem says, “like Nebraska,” “many Nebraskas,” “Nebraska is a little funeral”—my apologies to the real Nebraska!).

FWR: In “Dream with Omen,” you end the piece with “I would like to rest now / with my head in a warm lap.” This is one of my favorite lines, because it both speaks to the sound and feel of this collection, and it interrogates the two balancing aspects of this collection: that of memory and the mind, and that of the physical present. The speaker in many of your pieces seems to be constantly grappling with the subconscious world, made alive by dreams. How do you view or negotiate the separation and/or melding of the subconscious and the “real” world? Does the mind and its preoccupation with the past stop the self from fully engaging in the present? Can the speaker rest in a warm lap and still accept the darkness of the subconscious?

WL: In putting together this book, I became conscious of how often I write about dreaming and/or sleeping. I felt sheepish both because we are told often (as writers and as people) that dreams are boring and because maybe these poems betray my personal tendency toward indolence.

It’s interesting to align the past with the subconscious and the present with the “real” as you do in the question. I do feel the tension between those things in writing even as I also feel that thoughts are real and fears are real, etc., just as senses—how we experience the physical world—are real. And it feels a little silly to say this but I have a kind of faith that our subconscious is working away trying to help us come to terms with what occupies us in the real, present world even as we sleep and dream. Everyone who writes has at times had that sense that what they are writing is received, as if they are tapping into some other world or force. Maybe that idea is analogous to what I mean.

Memories, dreams, the subconscious, however the particularities of the mind manifest, feel consequential in their bearing on lived experience—they are how the real world lives in us. There is no unmediated world. Or if there is, we don’t know it. We must encounter the world personally because we are people. All this is to say I’m still learning line-to-line, poem-to-poem how best to articulate that kind of interiority in a meaningful way, without leaving the reader adrift. Leaning on dreams can make a poem feel muted and entering memories can feel like putting on the heaviness of a wet wool sweater and those things do not always serve the poem. I hope for my poems’ sake that I get that balance right more often than not.

Willie Lin was interviewed for Four Way Review by Simone Menard-Irvine.

Simone Menard-Irvine is a poet from Brooklyn, New York currently pursuing and English degree at Smith College. Her work has been published in HOBART and Emulate magazine.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview

AXOLOTL BY ANTHONY GOMEZ III

When wildlife conservationists released a dozen axolotls into the waterways in an abandoned town not far from Guadalajara, they were surprised to see the pink salamanders swim within the water for less than a minute. The endangered creatures jumped out of the pool on their own.

Eleven of them moved to the side and chose to die rather than learn to live again in this human-created habitat. Their smiling mouths stayed that way as they flopped along the dirt. Meanwhile, the last survivor came out of the water. It regarded its dying friends and marched down the road. The conservationists could not explain what was happening, but this last axolotl popped into a stranger’s home and, though they later tried to find it, they could not. The attempt to save the species was deemed a disaster.

*

Some years ago, on a flight from Tokyo to Guadalajara, I gave in to the cardinal sin of air travel—I spoke to a stranger. In the middle of the flight, when all those around me were asleep, I saw a slow set of tears fall from a Japanese woman’s eyes and disappear into her jeans. Hours to go, the short aisle between us was an insufficient chasm. I could not ignore the scene. So, I asked her what was wrong, and she confessed in carefully selected English that she was on her way to bury her son.

“But I’m not blaming Mexico,” she pleaded, as if I thought she was the type to blame a whole nation for a single incident. “He loved the country and the cities. Never had a bad thing to say.”

“What did he do there?” I asked.

“He learned to cook. He studied the cooks in the kitchen and the cooks in the home. Always, he said, Mexico produced the greatest food. He wanted to know why; so, he moved there the moment he became an adult. Would have been three years in a couple of days.”

“I think I would agree with his assessment. It’s a wonderful food culture.” The way I said it, with a remove and a distance, must have exposed my relationship to the country as also removed and distant. She had a wrong initial impression.

“Oh, I’m sorry. It’s terrible. I assumed because of your being on this plane and your…your look…you were from there.”

“I have family and friends I visit in Mexico. But no, I’m not from there.”

“It’s terrible of me,” she said. “I could have asked. I’ll…I’ll do that now. What takes you to Mexico? Those friends and family?”

“A cousin of mine passed away. One minute Alfonso was talking, then someone noticed him stutter. His heart was giving out. Then, it did.”

“Seems the airline put the grievers together.”

I looked around. We were the only ones awake. She might have been right.

“Weird, isn’t it?” she wondered, aloud. “To be on a flight to claim a dead body? I have never been to Mexico, and the moment I go it’s because I am on my way to see to my son’s death.”

Strange way of putting it, I thought, but she was right about it being weird.

Alfonso was a favorite cousin, an adult while I was a teenager and a teenager while I was still a child. Separated by less than four years, our minor gap in age nonetheless left him wiser and more experienced. When he was around, I ran to him for the sort of advice one is ashamed to steal from parents. He was dead at thirty-two and it seemed I’d lost a lifeline. Navigating a future without his guidance left me feeling adrift.

“We don’t need to speak about our dead,” she said. “One should remember them while one is happy to remind oneself they’re gone, or when one is sad to remind oneself of what one had.”

If that was true, then which emotion was she experiencing? What attitude toward her son possessed her that she preferred to think or speak less about him?

“Did you enjoy Tokyo?” she asked.

“It was a disaster of a trip, I’m afraid. I never saw it.”

Disaster was an adequate term. After a fourteen-hour direct flight, I’d landed in the airport, found the exit, and noticed on my phone’s home screen a long list of missed calls and texts. I sighed as I listened to each voicemail, and as I read each text. All of them were variations of the same sad news. I went to the bathroom, found an empty stall, and started to cry. I let that pass and then found a flight out.

Nine months of planning and fighting for this trip fell apart. It was a fight to get the time off from my data entry job, the courage to do it, and the money for two weeks abroad saved. While the first requirement wasn’t initially approved, a set of company layoffs I couldn’t escape made it all possible.

I booked the trip for no purpose other than a want to get off this continent. I suppose what I wanted more than anything was to go somewhere I could be lost, where I did not speak the language, and where I did not possess an overshadowing familial history dictating each sight or town. My journey was to see how I would adapt to a different culture—and if I could. When I called Alfonso to tell him about the trip, he described his favorite film Ikiru and said I should search out locations from the film. I didn’t bother to argue most of the film was shot on soundstages. I replied that my knowledge of Japan came from horror films and books by Ryū Murakami and Yoko Ogawa. None of those, I prayed, were accurate precursors to my trip.

Alfonso had not traveled much within Mexico, or outside of it. But there was one story about Japan he could share. He once heard reports of travelers who visited. The first Mexicans to the country reported arriving on the land, journeying from one place to another, town to town, until suddenly, they were unable to continue along a path. Blocked by a wall which could not be seen. Some claimed the wall was the product of spirit. Some said the travelers brought this fate over, and others said it was a uniquely Japanese magic. They learned there was one solution. Secrets could bring the walls down. The travelers had to give some truth about themselves up, else their journey was over, and they had to return home.

“Did they give up a secret?” I asked Alfonso.

About to tell me, Alfonso stopped to laugh, and suggested a different ending: “Would you?”

I did not explain my relationship with Alfonso to her. No, she wanted to get away from grief. We moved on to different topics with ease—like a spell had fallen upon us. So few people in life make conversation easy and pull from your soul the language and books and narratives you want to share. I almost lamented losing her to the nation once we landed. Even now, for comfort, I can close my eyes and imagine her listening as I confess my troubles and dreams. On that plane, in hushed voices so as not to wake anyone, we ceased being strangers.

As we landed, there was one final ritual to perform, one I nearly forgot.

“It’s Song Wei,” she said.

“Sorry?”

“My name. All this time and we never asked each other for our names.”

Of course, something as wonderful as a song, as music, defined her name.

“Mine is Carlo.”

The lights rushed on. Passengers quivered from the sudden transformation of noise and energy, the attendants raced down the aisles, they reminded us of the rules, and we prepared for landing. An orchestral track played over the speakers. Slow, it nonetheless had a familiar quality. Bernard Herrmann? They had to be joking. The score belonged to Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Its eerie sound continued after we hit the tarmac and as we exited the plane.

*

Taking care of Alfonso’s relatives, hearing them talk, and listening to plans for the funeral throughout the day took a lot out of me. That first day, I fell asleep early and easily when I returned to the hotel. By my third day back in Guadalajara, I had adjusted to the time difference and managed to stay awake long enough to enjoy a drink at the hotel bar. I sat across from the bartender, whose long and curly hair bounced as she prepared drinks. After finishing my cocktail and paying my tab, I crossed the lobby to the elevator, and suddenly there was Song, her arm wrapped around a man’s. Dressed in light linen, he looked local enough, while Song Wei wore a blue floral summer dress. We locked eyes, and she waved without an interruption. She hoped to see me later. At least that’s how I interpreted it.

“Excuse me.” I returned to the bartender. “There’s a Japanese woman by the name of Song Wei staying here. If she asks or if she sits at the bar, could you hand this to her?” The bartender nodded, her curly hair falling into her eyes.

I left a note with my name and a suggestion that Song have the concierge call my room. Including the room number felt too intimate, implicating myself as interested in only one thing.

Upstairs, in bed, I mentally reviewed the look the man on Song’s arm had given me. In between these thoughts, I wondered if the bartender would know Song from all the guests in the hotel and if the note would ever be delivered. To my surprise, an answer came at four in the morning. The hotel’s telephone rang. I put the receiver clunkily against my ear.

“Carlo?” Song asked.

“It’s me,” I said through a mistimed yawn. “I saw you earlier and thought if you’d ever like to talk—”

“—Yes,” she interrupted. “I’m in the hotel bar now.”

“Now?”

“Yes, it’s not open, but I have a story to tell you.”

I must have yawned—an instinct from the hour—because she began to sound a bit more urgent.

“Please, Carlo, I do think I can trust you on this matter.”

Two in the morning, seven in the evening, or three in the afternoon. I would have come to her no matter the hour.

*

Down the elevator, through the lobby, and toward the bar, I passed the bartender who was mopping the floor. She smiled, but I missed her eyes because her hair fell over them again. I turned the corner.

Without people, the bar was anything but a marvel. Brown chairs surrounded three empty glass tables. Earlier, these were occupied by working businessmen and their laptops. The bar itself was a wooden platform with a golden top and a long mirror behind the bottles. Seven barstools fit along it. All but two were flipped up, and Song Wei was sitting on one. Her dress had a quarter-open back. Long, black hair obscured much of her bare skin. If others could see us, it wasn’t hard to fathom Their impressions: questions or snickers about the older woman and a man half her age gathering so late in a closed hotel bar.

Amber light from dusty overhead bulbs filtered the whole bar into filmic twilight. It had the effect of rendering her body as the one piece holding all of reality together. She leaned forward, and in the mirror, I could see her hands resting on the bar, one over one another, her eyes darting forward.

A few seconds passed before I said hello. She turned, and though she had invited me down, and though she should have noticed me in the mirror, she acted a bit startled. The following smile seemed an afterthought.

Her hands did not come apart, and as I came closer to take the seat beside her, I realized it was because her palms held the thin ends of a transparent plastic bag together. Water in the bag came up to half the length of her arm, and in it was a pink axolotl. The salamander looked away from both of us.

“I’m glad to have found you, Carlo,” she said. “I don’t know if I can trust anyone else. It’s not like I have friends or family here.”

I could have snapped back: What about the man? Two of you looked cozy enough.

I stayed quiet.

“I went to visit my son’s living quarters when we landed. Talked to his landlord. Talked to nearby neighbors. Talked to them all in a terrible Spanish that should have me arrested. He was such a quiet and professional man that they didn’t have much to say about his life, personality, or hobbies. All his friends were local cooks at nearby restaurants, and that is where he spent most of his time. I thanked the neighbors and was let inside. A spartan, my son did not seem to give dust a fighting chance. Not that it was hard, the way he lived. Books about food and notebooks filled with recipes were the only real sign a person lived there.”

The axolotl in the bag started moving. Small arms pushed against the bag’s bottom. With a large and wide yawn, it reminded me of the hour.

“I pored through the notes and the writing. My son possessed a variety of talents. Penmanship was not one. Recipes and ideas for dishes require an academic to translate his handwriting. I’m not one. All I have brought back are the legible notes.”

She pointed her nose down. The encouragement led me to notice a small dark purse on her lap. Not wanting to release her grip, she used her nose again to direct me to open it.

“Please, look at the first recipes,” she said.

I opened the purse. Doing so felt intimate. It was filled with banal clutter—makeup, tissues, and tampons—and I had to dig to pull out the papers. Two condoms almost fell out of the bag as I did so. Those did surprise me, and I wondered if she intentionally brought them to Mexico despite the trip’s despondent purpose, or if she always carried those around. I remembered the man on her arm from earlier and shivered to burst the bubbles forming in my loose imagination.

At last, I found the index cards and loose sheets. Most of the recipes described or listed the ingredients of common cuisines. Mole. Aguachile. Cochinita pibil. None of these were so unusual as to require physical study. As local and delicious as they were, these were familiar dishes—a mere Google search away for anyone interested in the nation’s culture. But then I stumbled on the second to last recipe. The poor script would render any interpretation uncertain, and it was difficult to make out what the writer described. All I could decipher was one word: axolotl.

The axolotl in the bag seemed to read my mind. When I looked up, both the amphibian and Song were staring at me.

“I have to ask you a favor,” Song started. A real sense of urgency stole her voice, as if my decision could save or defeat her life. “I found this axolotl in my son’s room. Please watch over it. You saw the card listing it as an ingredient. I must know what my son wanted to make, what he wanted to use it for. It’s the last way to understand him. And, already, there are others who want to know too.”

Song released her hands, and unless I wanted the water and Axolotl to splash to the floor, I had to reach out. With my right hand, I did just that, and caught the top of the bag as the water threatened to spill. My palm became wet. The axolotl swam back to the bottom.

“Thank you,” Song said. She placed both her hands over my left one, looked me in the eye, and said it again. “Thank you.”

*

Retreating to the room with the bag in hand invited stares from the few night-shift workers. Kind smiles and professional grins from earlier disappeared into accusatory scowls. What could I be doing with such an endangered animal?

Online, I researched how to care for the axolotl. I filled the bath a quarter high and placed the creature inside. I stood there and wondered what I’d gotten myself into. Song promised she would see me tomorrow night, when she had dug around her son’s house a bit more, and when she could confess more about her findings. But what did I know? Even now, I had not learned her son’s name, who that man was, or why she felt the need to turn the axolotl over to me. Not that I was in the practice of asking questions at the right opportunity. Wouldn’t most men have pushed back against a stranger—even one like Song—thrusting a responsibility on them? Wouldn’t most have wondered why a chef from Japan felt the need to cook the poor, endangered amphibian?

Back in the U.S., the axolotl is largely banned. The level of damage they pose to environments outside their own is catastrophic. I did not know if these warnings or legal boundaries applied to Japan. If so, was it the danger or exotic quality of the axolotl that drew in Song and her son?

There were other matters to attend to. In the morning, Alfonso’s mom wanted me to speak with a florist, and a caterer, and a priest to settle the ins and outs of payment. The outsider, she thought, might best negotiate the price. Terrible logic. All she wanted was me to pay. Alfonso, you bastard, if you weren’t my favorite cousin—

The hotel telephone rang. I wondered if Song forgot to mention something, or if she would maybe want to come here. But it wasn’t her. I picked up and sat at the far edge of the bed.

“You’re wrong if you think her son wanted to eat him.”

A woman’s voice? Strong and stern, it wasn’t familiar. The caller continued:

“Her son liked to cook and loved to study recipes, but he wouldn’t eat the axolotl, not after getting to know the little guy. He had common sense.”

From where I sat, I could peek into the bathroom. Over the tub’s edge was the axolotl’s tiny head and pink hand-like claws helping it to hang on. It appeared to eavesdrop.

The caller continued. “Did you know axolotls were named after a god capable of breathing fire and lightning and regenerating its body? Believe it or not, an axolotl can still do two of those things.”

“I believe you.”

“You don’t sound so impressed.”

“I’m more curious how you know so much. How you know I have the axolotl? How you know about Song’s son?”

I rummaged through my luggage on the beside floor. The Death of Ivan Ilyich lay on top of my clothes. The book was the basis for Ikiru. Earlier, I planned to tell Alfonso I read it while in Japan.

“Do you know how important axolotls are in Mexico? You don’t carry one off without half the country speaking about it. People talk. People gossip. And some people? They’ll fight to save the axolotl. Or they’ll fight to kill it. Song’s son attracted all kinds of attention with what he wanted to do. That card in his collection? It is only partly a recipe.”

“What was he doing, then?”

“Attempting to recreate their habitat.”

“Did it work?”

“Not at all. But at least he tried. His home resembled something between an aquarium and a mad scientist’s lab. They have one native habitat left back in Mexico City. Hey, you heading to Mexico City any time soon?”

“Wasn’t planning on it.”

“Well, if you do, drop him off in Lake Xochimilco.”

“If you’re so interested in returning him to the lake, why trust me—a foreigner?”

“Because it’s your choice. She entrusted the axolotl to you. The lake is on its way out, you know. Too much pollution over the years. Because the axolotl can clean it up, and because there are so few things in life like the axolotl that can erase a history of human error.”

“To be honest, it’s not that I don’t trust you, it’s that I can’t quite see how one axolotl is so important. All Song wants is—”

“—Song. Song. Song. Get your sex-deprived mind out of the gutter and listen to me. Unless you want Lake Xochimilco to dry up and die, you can’t give the axolotl to anyone. It’s your choice whether you get him back to the lake. Until you decide his fate, don’t leave him alone at all. And don’t let Song eat him.”

*

The caller promised she would call each evening to ensure both the axolotl and I were safe. Part of me liked having a discussion to look forward to—even if I didn’t understand it all. Since Alfonso died, I hadn’t talked in-depth with someone.

Well, except for Song.

Because of this lack of practice, I forgave myself for having lost the habit of learning names. The caller came and went without one. I had almost done the same with Song on the plane until she offered it to me in an equal exchange.

But names are important. They are spells unto themselves. Take Lake Xochimilco. In the language of the Aztecs, the name refers to a flower field. (And no, I didn’t just know that. I had to look it up.) My point is that the name—Xochimilco—endures to tell us what was once there. Even if the land no longer looks like that, even if time and evil corrupt the earth and prevent flowers from growing, Xochimilco reminds us of what once was there.

That wasn’t all I found. Unable to fall asleep, I scanned stories about the place.

Lake Xochimilco is the last of a beautiful water network that survives a history prior to Spanish contact. Colorful boats float along the water and gardens grow along these vessels to sustain a forgotten and beautiful agriculture. Once a common sight, the number of boats has dwindled, and the tradition has declined with the lake. I watched a video on YouTube of a farmer who explained the lake was a living and breathing being, dying by coughing its last breaths. The water turned black and wondrous gardens burned up. What was left was all that was left…

The morning came, and with it came the lightheaded hangover of inadequate sleep. But there was no time. I had to visit the florist to prepare the bouquets for Alfonso’s funeral. Unable to shower because the axolotl occupied the bathtub, I simply changed and dressed. I was halfway out the door when the stranger’s warning from last night struck my brain: don’t leave him alone. All I had was the plastic bag from yesterday and, as I transferred him over, I felt the need to apologize.

“I’ll find something more comfortable for you later,” I said.

*

I walked through the town’s empty streets to a soundtrack of water slapping. Shuk. Shuk. Shuk. Holding onto the axolotl this way, I imagined that the bag would simply slip from my hands. Every few yards, I looked down, saw his smile, and felt relief he was alright in there.

After meeting the pastor and the caterer, I had one last task: ordering bouquets from the florist. Above the blue shop, a bright yellow aluminum sign was half faded, and the business name Flores looked to have been replaced green letter by green letter multiple times until each letter was oddly sized and shaped. On the window was written in white a common slogan: digalo con flores. Say it with flowers.

The inside was anything but falling apart. Black and white tiles looked new, and an art deco chandelier was touched by the sun, sending short shimmers of gold in the few open spaces between orange marigolds and pink dahlias. If Alfonso had a favorite flower, I had no clue. Who knows something like that about their cousin? Marigolds felt too stereotypically Mexican, and I didn’t want to choose a pink flower for a funeral. The florist ignored the axolotl, heard my concerns, and brought out several more plant types and said names I could not catch. The last one she brought out was purple, and she said the name in English: “Mexican petunias.” I agreed to it immediately and was happy to see that she could supply enough for the service. Not many people are interested, she said, and that surprised me given their beauty. Of course, once I paid, she told me the truth. Many in Mexico consider them a weed.

I decided to take a roundabout way back to the hotel, through dusty streets and over incomplete sidewalks. As I passed a bank a block away from the florist’s, I saw a familiar face leaving its entrance. He wore the same linen shirt as the man who held Song’s arm.

The man did a double take upon noticing me and seeing what was in my hand. He squinted to believe what he saw was real. That was all. I kept waiting for his attack, for a word, for him to rush and attempt to steal the creature. It never happened. I watched him move down the street, turn, and disappear.

Inside the bag, the axolotl’s pink face grew worried, as if it sensed what was coming, as if warning me. I was too loose, too carefree, too eager to see Song’s lover turn away. Suddenly, I felt my feet stumble—I had been pushed hard from behind. The bag never had a chance of being saved or held tight. Out of my hands it went, and by the time I regained stable footing, a puddle had melted into the ground. The axolotl flopped around.

“No!” I shouted.

Behind me, two men in wrinkled t-shirts ran forward. One knocked into me and started stomping hard. The other aimed a punch at my face. All I could do was fall to avoid being hit, and the attacker flew forward. The stomping man did not have much luck in crushing the axolotl. He resembled a rhythmless dancer. I stood and charged headfirst. Not much strength was needed—and a good thing because I don’t have it—to launch him back. He staggered into his partner, and the two collapsed to the ground. Their falling reminded me of goofy vaudeville akin to the Three Stooges. But this scene didn’t exist for me to laugh at. While the partners helped each other up, I grabbed the axolotl—a bit too roughly—and started running.

*

How long could an axolotl live without water? The number was not something I had looked up, or something I wanted to discover. Luckily, I was not far from my hotel and, like a madman, I raced to the fire stairs for the third floor. In the frenzy and worry about reviving my friend, I did not notice that I never used a key to get inside.

The door to my room was already open.

Alone, I drew the axolotl a fresh bath, dropped him in, and relaxed when he dashed from one end to the next. I cleaned a large red lunch container that could replace the plastic bag and better hide him. Surviving the attack evoked my mystery caller’s warning: some people will fight to kill it. I wondered if Song had already cracked this mystery when she forced the axolotl into my hands. When the phone rang, it was the mysterious caller, keeping her promise.

“Are you disappointed it’s not Song?” she asked.

“Only because when I see the axolotl, I think about her, and her son, and this man I saw on her arm. I saw him again.”

“She’s finding all those who knew her son.”

“To get to know him?”

“To know herself. She’s a biting and corrupting force. Part of that is because she’s lost her son, the other part is because when she had him, she took it for granted. She didn’t know how much she polluted the world with her sour thoughts.”

“Isn’t that just grieving? You judge so harshly when the same can be said about me. I lost my cousin, Alfonso, and when he was around…well, I didn’t always realize how important he was to my life. Are my opinions polluting the world?”

“Oh, yes,” said the voice. “And it’s terrible for the environment. Think ill of life and eventually you make life around you sick. You begin to lose sight of what’s important. You begin to forget who you are. You begin to lose your name and the names of others.”

“I keep forgetting to ask for names.”

“Would you like mine?”

I paused. “I don’t deserve your name now because I think…I think I’m sick, if I follow your definition of illness. I think about my cousin who passed. I don’t know what life will be like after the funeral tomorrow. That puts an ending on things, and I’m not like Song. There’s no mystery to unravel. He simply died while I knew him—knew him better than anyone.”

I worried the caller had hung up because the line was too quiet. All I heard was the wave of bath water from the axolotl swimming around. Then, at last, the caller’s breath.

“You’ll remember,” she started, “that there is a tomorrow. Each time you close your eyes, you will get closer to it. Until then, your thoughts are harmful. Remember that.” With that the line was disconnected.

A peace existed in the idea of a tomorrow without the sting of grief. But I also remembered how quick of an intimacy grief inspired on the plane, when Song and I overshared thoughts this caller might classify as pollution. Believing in the caller became much harder when there was a power to sustaining grief, and a time for it.

I didn’t want to leave the axolotl alone to head to the bar or take him away from his happy place. I regarded his smile as a reason to keep my promise to protect him. I ordered a mezcal sour to the room. Before long, there came a knock, and the barwoman handed me the cocktail. I watched the woman leave. There was a couple at the end of the hall. They were embracing, holding one another close, and when they kissed it was as the last step in a procedure. Now they could stumble inside the room. The woman, while I wasn’t sure, looked like Song.

*

Song was immune to normal, waking hours. She came to my room exactly twenty-four hours after our meeting in the bar. She marched straight in and looked toward the bathroom.

“The axolotl is alright?” she asked. She watched it swim back and forth. “Workers in the hotel told me you had quite the scare.”

“Two men attacked me and tried to take him.”

“Word gets out when it comes to these strange things. A woman at the bar told me she saw you run inside without the bag and I…I guess I worried.”

“You couldn’t be too worried,” I snapped. “To come at this hour. To not even ask about my state.”

“I only heard the story a few minutes ago. I was preoccupied until then.”

“Bet you were,” I let slip, succumbing to a jealousy I had no right to claim.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Song cried. “I am searching for something my son uncovered, something to bring me closer to him in this foreign place.”

“Maybe…” I sighed. “Maybe I just didn’t know that watching the axolotl was going to invite some people to attack me—and it.”

“My son wrote in his notes that the axolotl cleans the world. It eats the very things that poison humanity. For some, it’s easier to see the world suffer.”

“And yet, you still want to eat it? I heard your son wanted to save it. He tried to build it a habitat. He tried to—”

“—My son wanted to eat it…and…I am close to understanding my son. Another day. I promise Carlo…I promise it’ll be worth your while.”

Song did not stay over. We did not collapse into the bed as I imagined she’d done. She simply hugged me close, and in that embrace I felt strange. Intermixed with a lust for her I recalled the longing to speak with Alfonso, to share criticisms about life, and simply laugh.

*

I brought the axolotl to the funeral. What else could I do? Dressed in a black suit, I must have seemed a strange sight with the red container like a toy in my grip. However, the guests, perhaps simply polite, never said a word as they passed me, apologized for the loss, and regarded Alfonso’s body at the far end of the church. The exception was Alfonso’s mother, who asked to look inside the container. She smiled when she saw the axolotl’s smile, and confessed a truth:

“The axolotl is named after a god. In some stories, this god guided people to Mictlān—the underworld.”

I didn’t ask her what happened there because we were summoned forward. Alfonso’s funeral began.

*

My hotel room was trashed. Did I expect anything different? Sheets thrown to the ground, the bed torn apart, my suitcases searched and clothes everywhere. Books open, laptop gone, even the lint from my jacket inspected. I was thankful they had left my passport—stealing was not their goal. I should have hurried out, except I knew the axolotl needed to breathe again. I had brought new water to the tub and did not want to risk removing him too soon. I shoved the dresser near the door for security and waited out the rest of the day.

The female stranger’s call came in that short hour before evening.

“Everything is heading toward ruin,” I said. “Someone searched through my room!”

“Your thoughts!” she cried.

“All this for a single, damn axolotl?”

“Didn’t you hear me? They’re important to the country and its history. Some people will—”

“—Yeah, yeah. Some people will fight to kill it. They’re not so innocent. They’re banned back home in the states because of the environmental danger they pose. I’ve had enough of your warnings. I’m tired of strangers attacking me for carrying him around. I’m tired of not having help. I’m tired of a stranger calling me.”

“Control your thoughts.”

“What is that doing? Nothing I think will kill the lake or the axolotl or even me. What’s there will be there tomorrow, and if it’s not, it won’t be my doing.”

“I can’t speak to you if you’re like this. You’re twisting my words.”

I sighed. It calmed me. Alone, I didn’t want to lose this companion too.

“I’m sorry.”

“You remind me of Song.”

“Remind you? Earlier you mentioned her son, and you talk about her like…like you know her well.”

“Do you still trust me?”

“I just want less mystery. Everything in Mexico so far is mystery after mystery.”

“That’s life for you. Take Song as a warning. She’s disappeared into her thoughts and that made her disappear into others. She needs another’s touch to remember reality.”

“She told me the best time to remember someone is when you’re happy or sad.”

“She’s wrong. The best time is when you need to.”

“All I know is I saw her again in the arms of another guy.”

“There’s nothing wrong with love. There’s something wrong when it’s used to distract from the pollution you’re creating.”

I closed my eyes. Lake Xochimilco came to mind, and I pictured colorful flowers decorating boats slowly skimming along the surface. As the scene played out, the ship broke down, the flowers lost their color, and the lake its water. Left was waste and sewage and dirt. Flopping in this disaster were several other axolotls. If I opened my eyes, then the sad state of the lake would have convinced me of the caller’s wisdom. But I didn’t.

The scene continued to unfold. Alone beside the lake, I pictured myself leaning over its edge. The waste and sewage vanished. Water started rising. The floating gardens returned. And soon, the water’s deep hue reflected my face.

Song’s son wanted to recreate the axolotl’s habitat, the caller had said. Achieving the goal would have given them another chance for survival. It didn’t work but he tried, and that was the beauty of it. Song may have been wrong for simplifying her son’s ambition, wrong for ignoring how he aspired to heal a piece of the world, but the caller was just as wrong for pushing me to focus foremost on the disasters we humans create. Some may want to kill the axolotl, but some—the caller said—would fight to save it.

To hell with both of them—I decided—I was going to save it.

The caller said nothing else. She hung there, her breath audible until it wasn’t, until she hung up.

*

Song came again at four in the morning. A large grin stretched across her face, and she held up an index card filled with neat Japanese script—her own hand. In this state of enthusiasm, the room’s mess never crossed her mind.

“I spoke with another of my son’s friends. Through them, I was able to comb out what my son wanted to make with the axolotl.”

Her voice grew increasingly excited. Her plan was becoming complete.

“I also spoke with the hotel. They agreed to let me use the kitchen. Come down in thirty minutes with the axolotl. Everything must be fresh.” She squealed like a child and hugged and kissed me on the neck. Days ago, I would have been relieved to see Song take the axolotl, to have felt myself thrown into the game of chance where my desires might be met with reality. Instead, I watched her leave and was even sadder.

I waited in the room, watching the thirty minutes shrink on my phone’s clock. I don’t know why I waited as long as I did. Did I expect the stranger to call me? She never did. I picked up the hotel phone to request a car from the concierge, as fast as possible.

*

I never heard from Song. I wondered what thoughts crossed her mind as I betrayed her wish. Perhaps failing at the recipe, being unable to cook the axolotl, made her feel closer to her son. I never heard from the other strange woman, though I glanced often at my cellphone, half-expecting to read unknown caller on the screen. I would smile because I knew otherwise, because I knew I would lift it up and hear her again. That vision never transpired.

I drove to Mexico City and chartered a bus to take me to Lake Xochimilco. When I stepped off the bus, the air was cool, refreshed by an earlier rain. Sad-looking trees swayed away from us. The sight resembled what I saw in the video: beautiful but vanishing.

A man I recognized stood at the edge of a short pier. It was too late to retreat. I tightened my grip on the axolotl’s container. Dressed in a white linen shirt, sleeves folded high onto his arms, he regarded me with equal familiarity.

“I recognize you,” he said. “From?”

“From a hotel outside Guadalajara. You were on the arm of a woman I met. I saw you again near a bank.”

Instinctively, my arm came halfway across my body, reliving the suddenness and survival of the earlier attack against me. He waited for my anxious energy to slow before continuing.

“That’s some memory. You saw me on the arm of Song?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I do remember your eyes—jealous and mean. You loved her?”

“I didn’t know her. Actually, I just met her days before.”

“She was a strange woman. It would be easy to say yes. Even, as you say, without knowing her.”

“And you hardly knew her?”

“She was the mother to a friend of mine. He was a curious fellow. Came from Japan and swore he would learn all the recipes of Mexico and perfect them and study them and bring them back to Japan. He was a hell of a cook. But he stumbled on an ancient recipe from the old world. Axolotl. None of his friends wanted him to cook one. He believed it worth trying. Where would he even get an axolotl, we wondered? Well, turns out at his front door. He found one that had escaped from a failed sanctuary.”

“I kept hearing he didn’t want to cook him, that he had other plans.”

“You’ve got it. That’s what happened. My friend changes his mind. He swears he won’t cook or eat him. He swears he’s looking into a way to save him. There’s just one place for him, though. Here, at Lake Xochimilco. Axolotls don’t have a natural habitat beyond it.”

The lake spread before us. A yellow boat floated along, and a worker on board put the tips of his fingers to the surface. Tiny ripples dragged along. My new acquaintance continued the story:

“I told her what I knew, but Song did not believe her son came to this conclusion. She liked to think he was simply a cook, not someone caught up in the world’s struggles. Completing the recipe might just…I don’t know…I don’t know what she expected. I have to confess; I watched the axolotl after his death. Yet she found me, and she took me to bed, and convinced me to surrender him to her.”

“What happened?”

“She woke one morning, and I remember her crying about her son. I never felt worse for sleeping with my friend’s mother than that moment. She cried and cried. The water fell to the floor. But here’s the thing, I tried to hug her, to help her, and couldn’t. The room around me looked like this lake a hundred years from now. Tainted. Gone. Everything became dust. She ran out with the axolotl. When I saw her again the following day, she was almost a different woman. She looked at me the way one might upon the world ending. Do you think she could move past the heartbreak of her son dying?”

I paused. “I think she’ll have to,” I said. “A stranger recently told me enough disaster, enough pollution in the mind, can destroy one from the inside. I’m learning the same is true for me and my loss.”

I would be heading back to the U.S. soon. No job and no story about Japan and no cousin to call when I needed.

I opened the red container, lifted the axolotl carefully, and released him into the lake. Not a moment passed before he disappeared beneath the dark water. I stood watching, and after some time, the man shook my hand and left.

Boats passed. The moon came out of hiding. Under its glow, the lake and its floating gardens already looked that much greener. I stayed watching. Not because I thought the axolotl would return, but because I realized I had never felt so alone.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Fiction, home

INTERVIEW WITH MÓNICA GOMERY

Mónica Gomery is a rabbi and a poet based in Philadelphia. Chosen for the 2021 Prairie Schooner Raz-Shumaker Book Prize in Poetry, judged by Kwame Dawes, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, and Hilda Raz, her second collection, Might Kindred (University of Nebraska Press, 2022) skillfully interrogates God, queer storytelling, ancestral influences, and more.

FWR: Would you tell us about the book’s journey from the time it won the Prairie Schooner Raz-Shumaker Book Prize to when it was published? In what ways did the manuscript change?