URGENT: NEWS OF THE DEATH OF HIBA ABU NADA by João Melo, trans. G. Holleran

Excuse my urgency, oh right-thinking beings

especially you translucent

and self-referential poets,

but one of our sisters,

the Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada,

has just died in Gaza under the shrapnel of a benevolent bomb,

sent by another God,

different from the one she spoke with

every day.

I hesitated to convey this fateful news

so hastily. Perhaps I should wait

for the leaden grey smoke from the bomb that killed her to dissipate,

while she, surely,

scrutinized the sky for a sliver of light and

maybe even

the last birds.

Or, more convenient yet

it’d be better to say nothing,

until today’s hegemonic oracles,

like all oracles,

circulate an official statement

denying it as usual

without any doubts

or uncomfortable questions.

But when I read

the last words of Hiba Abu Nada before she died,

I was moved to spread this news,

before her banner could be censored

by those who defend selective liberty:

“If we die, know that we are content and steadfast,

and convey on our behalf that we are people of truth!”

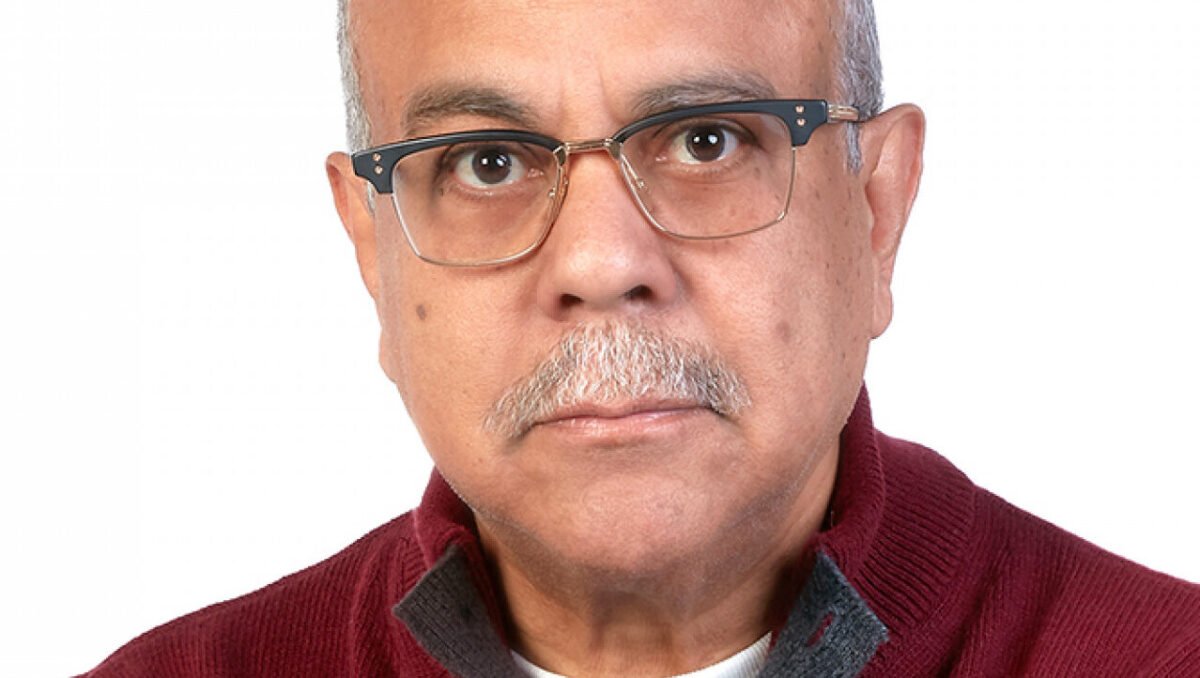

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Poetry, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Olivia Elias, trans. Jérémy Victor Robert

Day 21, Words Are Too Poor, October 28, 2023

words are too poor but I have only them

my only wealth

empty my hands & so great the sufferings

here again I press my arms around my chest

here again I get into this old habit of covering the page with little

squares filled with black ink

the little squares of our erasure

/

I write what I see said Etel Adnan* who knew a lot about

mountains’ strength as well as Catastrophe

I also know the power of this Mount facing the sea

Carmel of my very early days Mount Fuji of absence

& denial around which I gravitate above it the

black crows of desolation

as I know all about our Apocalypse which keeps on repeating

repeating the earth turning on its axis the sun that veils its face

/

here’s what I see

the madness of the overarmed Occupying State

crushing bodies & souls live on screens at least until

night falls a night of the end of the world only

pierced by ballistic flashes

in Sabra & Shatila the spotlights

. illuminated the massacre’s scene

today in this Mediterranean Strip of sand

. total darkness shields Horror

the sky explodes in a thousand pieces amongst

monstrous mushrooms of black smoke the time to

count one two three towers collapse one

after the other like bowling pins their inhabitants

inside then get into action the steel monsters

flattening the landscape they call it

(translation: converting this ghetto sealed off on all sides

into a 21st-century Ground Zero)

everyone wondering When will my time come?

& parents writing their children’s name on their small wrists

for identification (just in case)

/

no water no food no fuel & electricity & no medicine

decided the Annexationist Government’s Chief

let’s finish this once & for all & forever they shout

relying on the unconditional support of

their powerful Allies the ones primarily responsible

for our fate by writing it off on the bloody chessboard

of their best interests

as if their contribution to our erasure redeemed their crimes

Hear Ye Hear Ye

proclaims America’s great Chief, waving his veto-rattle

Absolute safety for the Conquerors

Hear Ye Hear Ye

chorus the mighty Allies

/

Gaza / 400 square kilometers/not a single safe place /2.3 million people /half of them children / hungry /thirsty/injured /desperately searching for missing family members dying under the rubble

& Death the big winner

/

they should know that souls cannot

be imprisoned no matter how tight the rope

around the neck & how strong

the acid rains & firestorms

One day, however, one day will come the color of orange/

/a day like a bird on the highest branch**

where we will sit

in the place left empty

in our name

in the great human House

————

*Etel Adnan, “I write what I see,” in Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito: Post-Apollo Press, 1986; Brooklyn: Litmus Press, 2021).

**“One Day, However, One Day,” from Louis Aragon’s homage in Le Fou d’Elsa (1963) to Federico García Lorca, who was murdered, in August 1936, by Franco’s militias.

DAY 74, THERE WILL ALWAYS BE POETS, December 20, 2023

instability a general rule

it seems a new ocean’s on the verge

of emerging in

Africa

& floating between

here

&

there

could affect not only people or land

but also the seasons I experienced it

of fall I didn’t see a single thing

this year the acacia’s

color even changed without

my noticing

one morning looking through

the window I realized

it was there

naked

at its feet a carpet of yellow

leaves littered the ground

nothing to keep it warm

exposed

to the cold icy rain missiles

& here I was & still I am

glued to the screen

startled by every explosion

of the red-little-ball

clinging to the glittering

garlands

as soon as one of the

flesh-eating-red-balls hits

the ground a sheaf of fire

bursts followed

by a huge black smoke

cloud

then

screams

cries

panic

agony

day & night (even

more so at night) keeps on

going the hypnotic

ballet

today

Day 74

74 days of this

will spring come back

or only a long winter

of ignominy cold hunger

history will remember

there will always be poets

to tell the martyrdom

of the Ghetto People

NOTE: An earlier version of this translation appeared on 128 Lit website, December 28, 2023.

HEAR YE, HEAR YE!

At regular intervals shaking his rattle carved with the word veto the Grand Chief of America takes the floor for an urbi et orbi statement

With the utmost firmness

broadcast on a loop

in newspapers on screens

around the world

withwithwithwithwithwithwith

thethethethethethethe

utmostutmostutmostutmostutmost

utmostutmost

FIR/MNESS

like

FER/OCITY

growing

exponentially

utmostutmostutmostutmosT

exceptionallyFirm

FIR/MNESS

FIRE/MESS

Iron balls blazing

in the sky

black & read whirls

it’s raining

black ashes

east bank not west

with the utmost

firmness

We support the Conquerors’

Right to Security

COLIN POWELL. GUERNICA. SCULPTURE

1

The devil is in the detail. Colin Powell–former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of State to the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush, between 2001 and 2005–was said to have placed great importance on this. Unfortunately for him and the legacy he leaves to history, he broke that rule on one memorable occasion

It was on February 5, 2003, when he called for a military crusade against Iraq on the podium of the United Nations, based on false evidence of weapons of mass destruction. His effort resulted in the very thing it was supposed to prevent–the deaths of hundreds/hundreds of thousands of Iraqis–& plunged the country into widespread chaos, which is still unfolding today

That day, UN officials covered with a blue veil a tapestry hanging at the entrance of the Security Council representing Guernica, the monumental work painted by Picasso at the request of the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War. Twenty-seven square meters commemorating the stormy & total destruction of the small town of the same name by the German & Italian air force, on April 26, 1937

2

In March 2021, the tapestry was returned to the Rockefeller family who had loaned it for 35 years & wanted it back. Has it been replaced? With what work? I don’t know, but I’ve got an idea. Let’s offer a cubist sculpture/assemblage of 550 stones extracted from our lands on which Settlers, protected by militias/soldiers & courts, are having a great time

Upon each of these stones

that capture the light so

beautifully

is an inscription: the name of

a village

from yesterday and today

that was

razed/ablaze

May a blue veil cover it when the Guardians of the ghetto & the bantustans take the floor

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

- Published in Poetry, Translation