AWAKE UNTIL DAWN by Pete Prokesch

After my brother Max’s funeral, everyone was invited to the Wolinski’s backyard for a barbeque. I stood next to the margarita pitchers and watched ice cubes melt away in the summer sun. I felt a hand on my shoulder every few minutes. I mastered my routine. I turned, delivered my best grimaced smile and hugged family, friends, and the occasional stranger, face pressed against their dress or button-up shirt, damp from the August heat.

“I’m so sorry Kaiya,” they said. “You were such a great sister,” or better yet, “Be strong.”

I cocked my head to one side, left a lingering hand on their back, and forced one last smile. Fuck Max, I thought.

Max’s friends crowded around a chain-linked fence on the far side of the yard under the shadow of a large maple. Max’s best friend chased another friend in circles around a lawn chair, wiffle-ball bat in hand, slapping at the man’s calves.

I reached into my purse for a pack of Parliaments and walked past the shrubs to the front of the house. Chris, Max’s high-school friend, stood alone on the sidewalk. He lived in Denver and was back home for the funeral. A murder of crows gathered in the road, pecking at a furry carcass. I lit my cigarette and squinted at the animal.

“I think it’s a fox,” Chris said. “I’ve never seen one around here.”

His hand quivered as he raised a fresh cigarette to his lips. A quartz bracelet hung around his pale, thin wrist and his gelled-down hair looked like it wanted to explode in the humid air. He patted his frayed pockets for a lighter. I reached into my purse for mine, took a step closer, and held the flame up for him.

We smoked until he broke the silence. “Remember the time—”

“Don’t,” I said. “No more stories.”

Chris nodded and pulled on his cigarette. A minivan whizzed by, and the crows dispersed into the air and roosted on the telephone wire, cawing in chaos.

“It came as a surprise to me—the phone call,” he said. He scratched the back of his head. “You know—when I found out.” He dropped his cigarette butt on the ground and rubbed it into the concrete with the heel of his shoe.

“Really?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Chris said. He pulled his white cuff over his bracelet. “I guess it could have been any one of us. Could have been me.”

I thought of Max detoxing on my parents’ couch the first time he got sober. Sweating and crying and vomiting into a pink basin. In high school, he came home from a blackout when my boyfriend Johnny and I were on the couch, watching Real World vs. Road Rules Challenge on MTV. Max stood over us with distant, vacant eyes. He threw a swift punch that broke Johnny’s nose. I screamed as Johnny shielded his face and blood spilled onto our blanket. Dad rushed downstairs and threw Max into a wall.

“What the fuck is wrong with you?” he yelled.

The next day we piled into the Toyota Camry and drove Max to the Falmouth Rehabilitation Center in Cape Cod. Mom pleaded with Johnny’s parents not to press charges. “Our son is very sick,” she told them. Johnny eventually stopped returning my texts.

I turned to the crows, pulled on my cigarette, and took a deep breath.

“I’ve been waiting for that call since I was twelve years old.”

Chris reached into his pocket and pulled out a pen and a crumpled receipt. He pressed the paper against his knee, scribbled a number, and slipped it into my hand.

“Come visit me if things don’t seem worth it,” he said.

*

Two weeks passed in my parents’ house. I dropped my summer courses and told the restaurant I couldn’t work until further notice. The periodic visits from neighbors and friends dwindled to none. Upstairs, Max’s room was preserved like a museum. Bed unmade the way he left it when Dad tried to shake him awake that morning. Laptop open on the floor—probably an episode of The Sopranos. A poster of Tom Brady and Rob Gronkowski engaged in a flamboyant high five during a Super Bowl parade. I stood at the doorway and looked in. I lifted a single foot into the air, but I couldn’t enter.

Downstairs, a basin of water and bamboo strips lay on the coffee table, with small beads of liquid collecting on the table’s polyurethane finish. Mom had taken up basket-weaving. She also thought it was the perfect time to get a puppy. Maxine. I refused to walk her.

Dad looked fat. He came home from work, drank two beers and read the sports section of the Boston Globe on his Kindle. Over a tin-foiled dinner from our neighbors, he asked Mom what kind of baskets she was making. Then he asked me if I planned to return to school in the fall. I did not. He grunted, washed the dishes, took Maxine out, and then drank exactly four Budweisers during the Red Sox game. He slept each night in the armchair, until I heard Mom creep down the stairs around three or four and beg him to come to bed. His stomach hung over his belt line, and his eyes looked tired and gray.

I booked my flight to Denver that night on my laptop, while smoking a joint through the bedroom fan in my window, the heavy cloud pouring out of my mouth, vanishing into the suction of the blades. I hoped my Airbnb was close to Chris.

I turned my phone off airplane mode—a habit I learned to do after my afternoon yoga class in an effort get everyone to fuck off. I texted Chris.

“Definitely not worth it here. I’ll see you in a few days.”

*

After going to the movies by myself, I met Chris on my second day in Denver. Mom and Dad thought that I was staying in my friend Lissie’s sorority house at the University of New Hampshire. I waited on a blanket by the pond and watched a gosling attack a family of ducklings.

Chris looked strange without his stained suit and uncomfortably parted hair. He wore a hooded drug rug with Rastafarian colors. He brought a small guitar and a duffel bag, with a large gold bowl and a small brown mallet. He stood next to me and chimed the side of the bowl, then circled the mallet around the rim, reverberating a harmonized sound. This was the same Chris who was kicked off the high school lacrosse team for testing positive for steroids.

He sat down next to me, gestured towards my brown-bagged bottle of red, and took a prolonged chug, his stubbled Adam’s apple bobbing up and down with each swallow. His eyes lit up after the swig, and he produced a guitar pick from his pocket and began strumming a single chord over the hum of the bowl.

“It’s about aligning your chakras,” he explained. “We have these tiny energy centers in our body.” He leaned over and tapped my sternum with his guitar pick.

It sounded like he was reading from a pamphlet. “I thought you played lacrosse?” I asked.

He smiled again and played an awkward riff.

Four geese floated towards the middle of the pond, retrieved the hostile gosling, and glided past the line of ducklings.

He glanced out at them. “It helps me,” he said. “If Max found something like this, maybe he’d be here.”

I took a long swig from the wine and lay back on the blanket, resting my head on Chris’s thigh. His leg felt familiar and warm. He played a clumsy rhythm, pausing and restarting from time to time. The wisps of white clouds moved fast in the blue, summer sky.

*

Chris told me he and his girlfriend lived two blocks away on tenth and Colfax. It was a gray, stucco ranch, and they lived in the unit on the right, marked by a Bob Marley flag hanging in the living room window. Inside, I met his girlfriend Maria who sat on a torn couch and took an enormous hit from an oversized bong. She gripped the shaft of the glass piece and delicately blew a cloud of smoke towards the stained popcorn ceiling.

“Maria, meet Kaiya. Max’s kid sister.”

Maria nodded and handed the bong to a sleeping, shaggy-haired man on her left. He woke up with a jerk, scanned the room, hopped to his feet like he was going to run, then sat back on the couch and took a rip.

The four of us played Mario Kart, cross-legged on the rug. I screamed when Maria blasted me with a red shell. She crossed the finish line first, and Chris yelled, threw his controller onto the couch and doubled over with his hand on my knee. He smelled sweet and clean. I scanned the room for Maria’s eyes, but her head was down as she rifled through the contents of her purse.

“Close your eyes and open your hands,” Maria instructed. I held them out, the left stacked over the right, like I was receiving communion. I felt a tiny candy fall into my palm, and I rolled it between my thumb and forefinger.

“Now open and rejoice!” exclaimed Maria. She took a hit from the bong but failed to clear the chamber, coughing smoke into the living room air.

I stared at the white chalky pill soaking up sweat from my palms.

“Percocet,” said the shaggy-haired man. His eyes were nearly squinted shut. “If you need any more for your stay…” he reached into his pocket and pulled up the corner of a Ziploc bag.

I looked back at the pill. I imagined Max staring down at the same image. I needed access to him, so for a moment, I pretended my hands were his. I inhaled and threw the pill into my mouth, grinding it with my molars and swishing it around to pick up the taste. It was bitter. I thought of Max again. All the bitterness he must have tasted. Then, the withdrawal, when we would stay awake until dawn, watching The Sopranos—matching each mobster’s personality to an aunt or uncle. I reached for Chris’s beer and washed it down.

*

I lay in the guest bed in a reverie between sleep and wakefulness. My skin itched in a pleasant way.

“You’ll learn to love the itch,” I remember Max telling Chris over the phone as Max paced around his bedroom, cigarette hanging from his mouth.

My mind drifted towards my first Halloween trick-or-treating without Mom and Dad. Max and Chris took me on their neighborhood route with a carton of eggs for any houses that kept their lights off and doors locked. I squealed with delight as the eggshells cracked against the glass windows, yellow yolk oozing down, until the lights flicked on and yelling ensued. My first throw landed in a bush, but my second toss yellowed the windshield of a Cadillac. Max hollered in hushed delight. I could not run fast enough so Chris, dressed like Neo from the Matrix, bent down, and I leapt onto his back gripping the leather collar of his jacket. The cool October air blew through the princess tiara tangled in my hair. Chris was large for the sixth grade and carried my ten-year-old body with ease, locking his arms under my legs and shifting me further up his back as he ran. Max dressed up as a Smurf and jogged in front. He looked back over his shoulder at the two of us, with his blue face, and opened his mouth to speak.

The bedroom door crept open with the glow of the hallway light. Chris slipped into bed next to me and gently placed a finger over my lips. I put it in my mouth, tasting the saltiness of his skin.

He kissed me ferociously, and I reached behind me, struggling to undo my bra. His weight hurt and his knee dug into my thigh, but I could feel my body for the first time in weeks. Tears welled in my eyes, and I wrapped my hands around his back and pulled him into me—kissing his chest, feeling the wisps of hair tickle my face. Like the pill, I needed him to dissolve me—to be engulfed by something other than myself.

He was fast and rough, and I thought of Maria as the metal bed frame danced on the hardwood floor. Maybe she was out from the Percocet or caught in the embrace of her shaggy-haired dealer.

He pushed on my face as he came, and I gasped, yet felt oddly safe, sandwiched between his weight and the softness of the pillow. He ran his hands across my chest and disappeared into the hallway bathroom. I heard faint weeping muffled by the hiss of the shower. Steam billowed out into the hall, barely visible in the light. Then I heard the murmur of Maria’s voice. I reached for my phone and booked a red-eye flight back to Boston.

*

A lot can change in a few days. I came home on a Sunday. Mom sat with her laptop at the kitchen island, hunched over, eyes squinted, with her face kissing the screen.

“Grief writing,” she said. “Creative nonfiction class.”

I looked up at the bookcase and noticed her basket-weaving supplies tucked away on the top shelf. A half-filled 501C form lay on the oak coffee-table, with a pen and a checkbook in arm’s reach.

“What’s this?” I asked and held it up.

“Dad’s doing it for addicted athletes. Remember that Celtics player from Fall River who overdosed and crashed his car? Well, Dad’s starting a local chapter here.”

“Where is he?”

“Evening walk with Maxine. He’s been doing two miles a day, plus thirty minutes on the treadmill.” She eyed the collection of Budweiser bottles in the recycling bin. The wrinkles on her face tightened, and her eyes looked wet in the light of the laptop. I flicked on a lamp.

“And UNH?” Mom asked, eyebrows raised.

“Too much partying,” I said. I went to the fridge for a glass of wine.

Upstairs I stood in the doorway of Max’s room. My neck was stiff, and I still felt the weight of Chris’s body. I inhaled deeply and walked in. Max’s first article for Spare Change newspaper, a paper written by addicts and homeless people, was framed above his desk.

“Restaurants for Refugees: How Local Businesses are Opening the Doors of Our Community.”

On the desk was a half-finished glass of water. I opened the drawer. A photo of him and his high school girlfriend selling T-shirts at the beach with matching pot-head grins. A pack of Marlboro reds, with only two left. I pulled out the pack and placed it in my purse. The bottom drawer of his dresser was slightly open. Unfolded blue jeans stuffed it to maximum capacity.

I lay on his sheets, still unmade the way he left them, and pressed my face onto his pillow and smelled his musty scent. Stale, but undeniably him. I sobbed into his pillow. It felt wrong at first and I kept it muffled, but then I let it go. Snot, mucus, and tears. My chest jerked, and I rolled over like I was writhing in pain. I heard Mom and Dad’s footsteps stop at the doorway. I looked up at them, their bodies doubled through the distortion of tears.

I laughed at Dad. “You lost like fifteen pounds in a few days.”

He smiled a pained smile.

“Do you want Maxine with you tonight?”

I nodded my head, and the pup braced herself, then awkwardly jumped onto the twin bed with me, curled at my feet on top of the dorky comforter, depicting white constellations in a red sky.

My parents shut off the overhead lights, and left the door open a crack. I turned my phone off airplane mode and got a text from Chris. In the darkened room, the light from the screen hurt my eyes.

“Going to rehab,” he said. “Finally seems worth it.” He added a praying hands emoji.

I thought of my brother crying on our living room couch. I thought of him begging me for money, saying his car was broken down, and he needed gas. I thought of the post-rehab Soprano marathons until dawn, and the gentle kiss on my forehead in the morning, for believing in him. How much I hated it now that I had believed in him. I recalled what he said to Chris on that Halloween night, smiling over his shoulder as we jogged down the street.

“That’s my kid sister,” he said to him. “You hurt her and you’re a dead man.”

I began to text Chris, erased my words, and responded with a heart.

I lit Max’s cigarette and watched the smoke rise and gather around the ceiling, then disappear through the crack in the door. I glanced back at the unplugged fan. The smoke would do as it pleased.

I dropped the ember of the butt into the cup of water and heard it hiss in the dark. I wrapped my arms around myself and imagined they were Max’s, then Chris’s, then Max’s again. Then I pulled the sheets close to my face to smell the memory of my brother.

- Published in Issue 21

DON’T CALL ME YOUR PRINCESS by Megan Culhane Galbraith

Once upon a time, there was a young girl who lost her mother too soon.

Cinderella’s grief was bottomless. Every day she visited her mother’s grave.

“Where is my great love?” she asked.

One day her mother answered.

“Cinder, dear, your great love is inside you. You must be yourself, for it is only then that your great love can find you. They may dress you in rags, you may clean a fireplace, but you are exquisite. Look deeper, honey. Let the love radiate from within. Be yourself.”

Cinder’s home life was messy. Her father had remarried and her stepmonster hated her.

Cinder did the dirty work and kept her head down.

Her stepsisters hadn’t gotten laid in a while, and they were extra mean about it.

As she cleaned ashes day after day, her mother’s advice clawed at her. “Love yourself first.”

“But how, Mother?” she asked.

Just then, a flaming ember burned her hand and a white-hot heat lit up within her. She remembered the bedtime tale of the phoenix her mother used to tell her.

She rose from the hearth and gave herself a smoky-eye by slathering the dark ash on her eyelids.

Cinder heard of a fancy dance in town, but she hadn’t been invited.

She was tired of waiting to be asked. Meanwhile, her horrible stepsisters paraded their sexuality like marriage was an endgame.

“Fuck this,” she said, and she decided to crash the Prince’s Ball.

Her friends Pinky and Bluey helped her get ready.

Cinder had the best time at the Prince’s Ball by herself. She adorned her hair with peonies plucked from the centerpieces. She slurped oysters, wiped her chin with the back of her hand, and burped. She requested the chamber orchestra play “Free Bird,” then twirled and laughed and danced like no one was watching.

But her stepsisters were watching. They were wicked jealous that all eyes were on Cinder.

And the Prince was watching, because, you know, the male gaze.

She’d admit later to her girlfriends that the Prince was great in bed, but he sold vapid promises and empty charms to all the other girls. He had a wandering eye. She’d seen the texts to his ex.

Cinder wasn’t buying any of it.

“Don’t call me your Princess,” she said.

She went where her desire led. She was safe, not sorry, because girls just wanna have fun, too.

So, she ignored the Prince’s lame texts, tested negative for the STD he said he didn’t have, and bought herself a vibrator.

She did what she pleased. She loved who she loved. Fuck the patriarchy.

Best of all, she finally came first.

And she lived happily ever after.

- Published in Issue 21, Uncategorized

EGG WISHES by Lucy Zhang

At the claw grabber machine, we take turns snatching second chances. The chances are stacked in rows: dyed and hollowed eggs, their pointed ends tilted like defective roly-poly toys. There’s no strategy; we’ll take any of the eggs so long as they end up in one piece, plucked by the claw, dropped down the chute, held still by the plastic covering. We wait patiently for our turn. The line trails around the air hockey table and pinball machines. None of us has anywhere else to be, to get to, besides the back of the line after the egg slips out of the claw’s grasp, and we count the coins in our pockets again—not that we’ll run out of money any time soon. This is an arcade of regrets: money goes slowly, time gets eaten first.

I don’t think Adam ever regretted anything, though. He’s probably in purgatory, lounging on one of those beanie cushions and licking Nongshim shrimp cracker dust off his fingers, watching souls drift by. He always gave off that vibe of nonchalance. It made people want to test how far he could be stretched. Indifference is a superpower, I told him. He shrugged.

We had once caught our classmates rummaging through Adam’s locker. Adam held my sleeve and we waited until they disappeared. They had taken five dollars from his wallet, all the cash he had. I ended up buying lunch for both of us; I could stretch my two dollars if I bought peanut butter and jelly sandwiches instead of a warm entrée. This worked out fine since we both liked peanut butter, although we’d scrape the jelly off into the plastic wrap—too sweet, I said. Too soggy, he said. After school, we’d head to my house and play with my dad’s Chinese yo-yo. Adam liked the yo-yo’s soft hums when you spun it fast enough; he said it sounded like wind. I thought wind didn’t sound like much of anything except a structurally questionable roof that might come down, but Adam found nature’s noises soothing. Sometimes Adam would stay overnight without my parents knowing. We’d hide his backpack in my closet and he’d stay quiet as I had dinner with my family, and then after my parents went to sleep, I’d tiptoe to the kitchen and put together his meal of leftovers: some rice, cold tomato egg, soy vinegar braised ribs. The microwave was too noisy, so I tried to soften the cold rice with soup from the meat. A whole bunch of randomness, I’d say whenever he asked what was for dinner. Then we slept in my full-sized bed, which he was starting to outgrow, his feet poking off the end. He didn’t talk much about himself and preferred pondering the universe—where did we come from, where would we go, what’s infinity. He never tried to touch me. I liked his company.

When it’s my turn at the machine, I push the lever and maneuver the claw above one of the striped and polka-dotted eggs. Adam would choose one of the pale eggs, one that still looks natural. I always found it odd that he seemed to prefer things in their pristine state—he refused to let his rice soak in sauces and boycotted apple pie in favor of the raw fruit—and yet he had piercings lining his ear and right eyebrow. Everyone goes through this phase, he had said. A phase of poking holes through your skin as proof of conviction, self-confidence.

I let the claw descend onto the egg. For a second, the egg shifts within the metal fingers, and I hold my breath, waiting for it to tumble out. But it stays and the claw rises and begins to move to the chute. It moves in horizontal and vertical lines, screeching with each shift in direction. I wish whoever engineered this machine could’ve made the paths smoother, less angular, more like a river than a road.

During Field Day, the school set up a dunk tank. Somehow Adam was voted to be the dunkee, maybe because, when forced under the spotlight, he always gave a big show when there was a crowd; he’d laugh or cry or gasp and then laugh again, dangling the gravity of a situation before our eyes before snatching it back and going gotcha. I was worried he’d overexert himself when he’d rather be curled up in the corner of my bedroom in the nook between my bed and the wall, and he hated the cold and he’d be going in and out of water. Plus, he covered his piercings with his hair; the water would surely reveal them. Why’d you get the piercings if you’re going to hide them? I’d asked. It’s about me knowing they’re there, he’d said. He claimed the dunk tank would be fun, although I suspect he was just trying to rationalize his fate: knowing he could head in one direction, up or down, not knowing when it’d change. That’s leaving a lot out of your hands, I thought.

You should participate in the egg toss, he said. I heard they were giving iPods to the winners.

I like to listen to music, but the arcade blares the same tune over and over. I never did win that iPod. I was no good at egg tosses, didn’t understand how to reduce momentum with my palms—the egg would crack as soon as it landed in my hands. But Adam won one for me after people lost interest in dunking him and he was allowed out of the tank.

The claw loosens its grip and the egg falls. It hits the edge of the chute and even though I’ve gotten used to leaving empty-handed, I’m still disappointed when it doesn’t roll into my hands cupped by the opening. The egg rolls to the side; the claw retracts for the next round; the lights flicker “GAME OVER”. Someone taps me on the shoulder—it’s their turn, I’m blocking the line. I shuffle to the side and watch them pop a coin into the machine. I begin my walk to the back of the line before I can see them reach for the lever. Somehow it hurts watching others come up empty-handed.

The day a group of students locked Adam in the custodian’s closet, I had a week’s worth of Ma LiPing homework to complete for Chinese school that Saturday. If I had any hope of passing the weekly quiz, I’d need to start memorizing characters as soon as I got home. It’s always easier to feel busy and fired up about homework when you want to avoid thinking about something else. Adam disappeared all the time, but homework didn’t—not unless I finished it.

No one ever said he was “bullied”— such a strong word. He didn’t consider it bullying either, although that’s probably what ended up eating away at him: wandering directionless, not a protagonist, without an antagonist. Perhaps I should’ve known one day he’d never come back, like a ghost you swear haunts the old box TV in the basement, only to remember it had been recycled years ago. Adam never liked TV, not movies or shows or cartoons, said they were too “static”—just boxes filled with willing prisoners. Those characters can only live in the box, I said. Not if they die, they don’t, he replied.

I still have a pocket full of coins. The line extends far into the depths of the arcade, where there aren’t any lights, just us players waiting our turn, standing in the dark. I don’t mind standing until my feet feel like they’ll snap against the floor, but it’s hard waiting days, weeks, months without seeing. By the time we make our way to the front, our eyes water while adjusting to the flashing colors, but no one looks away. No one speaks.

The silence leaves me with too much time to think. When I finally get my hands on an egg, the first thing I’ll do is ask Adam if I can see his piercings up close. I’m not sure if I want him to say yes.

- Published in Issue 21

LOVE AND LEAVING IN THE CONDITIONAL by K-Yu Liu

It’s not like crucial information wasn’t revealed in the early stages.

Lars and I, we met under the context of illicitness.

My boyfriend’s name was Léo. Tell him you have a boyfriend, tell him, I said to myself.

“My boyfriend is also an engineer,” I announced in an attempt to ensure that my initial attraction could not complicate itself.

It complicated itself.

One would have said that neither of us were cheaters—as if there were a specific size and shape and way of person who is predictably a cheater.

Lars was tall and slender, with striking facial features poised behind glasses made more for seeing than being seen. He had the emotional security of a youngest child with doting parents, and the social exuberance of a scientist who understood the currency of extraversion.

Men and women alike have called me overwhelmingly attractive but with a somewhat off-putting quality, likely the cause of my wary, analytical eyes and antisocial aura.

Exes would say that my interest is hard to capture but once seized, I am monogamous to a fault, tragically devoted, prone to melodramatic infatuation.

All of this is to say that neither of us saw anything coming.

*

Through my own interpretation of social cues, which would later prove to be cataclysmically faulty, I concluded that Lars had engaged in flirtatious behavior with me for five and a half hours. An unabashed compliment, a hand that finds my knee, a comment on the intimacy of a shared third language of French, a request for my number.

The media tells us that if one is a woman, it feels good to be seen. I thought I was being looked at, being wanted. It was a classic case of confirmation bias, a perfect environment for fantasy to brew: here was a Belgian electrical engineer, in New York for a semester of doctoral research, clearly attracted to me, likely looking for fun, relishing the recklessness of the city.

That night, after having scrutinized myself long and hard in the mirror trying to make an objective judgement about how I had looked, I watched the blurry image of Léo’s face lag on my phone screen. This was my partner for twenty months out of the twenty-four of our relationship: pixels from France doing their best to assemble themselves into an image of him.

“We’ve been talking about this for years, Léo. You know I can’t imagine feeling this close with anyone else.”

“Oui, je sais. You’re right—maybe it’ll make me appreciate you more.”

I said nothing.

“Du coup, euh…”

“Bref, euh… Okay. Bon. We probably shouldn’t see them a second time.”

“Yes. And no names, so we don’t try to find them online and compare ourselves.”

A flicker, and then his voice cut off.

“Allô? Allô?”

“Oui, allô? Tu m’entends? Hello?”

“Hello? Yeah I just said—”

“Yeah, you said no names, I heard.”

“Yeah…”

“Okay…” A pause. “Tu me manques.”

“Me too. I miss you too.”

*

The feeling of liberation is like a well-composed movie score. It accompanies all perception and increases the chances of acting out of passion.

Under scattered stars enrobed in the purple of twilight, I wore a carefully selected outfit on top of my body with every pertinent inch of its skin freshly shaved: I was Lars’ date to a university-wide social. Or so I thought. Four hours and three drinks later, Lars revealed that his copine was also a PhD student in psychology.

“Pardon? Ta quoi?” I almost demanded, incredulous. Instead, I counted to three, took a breath, and said, in what was surely an impassive voice, “Ah! Copine, as in friend or copine as in girlfriend?”

“Girlfriend. Cognition and perception psychology, though, not social and behavioral,” he said lightly.

Had this happened in earlier years, I would’ve thought, through the distress of shattering revelation, that the coincidence was some indicator of fate, or at least a justification for entanglement, a reason to test the limits. In hindsight, it seemed like a sick game of multiple conditionals. If a, then b. If he has a girlfriend, he can’t be involved with me. If he is flirting with me, he’s inviting me to transgress boundaries.

Sometimes I am more stubborn than smart. I tested the boundaries.

Lars walked me home. I weighed my options with every step, my facial muscles tired from the effort of masking disappointment. Even so, never before had I wished that I lived further away so to make my remaining time with him last longer. Pure affection for his person, or the thread of hope I still hung onto?

At my doorstep, ready to leave, Lars kissed me on both cheeks as before. I had a minute or two to act. All options seemed absurd, but rationality had long escaped my prefrontal cortex.

My question was likely uncomfortably straightforward but still polite: Something something I can’t kiss you? Chagrin rusts memory, it turns out.

Lars looked more than fairly surprised, and his response was a more than fairly resolute, “No.”

“Mixed signals” is what we settled on. Some over-friendliness on his part, some misinterpretation on my part, a few cultural differences between us. He apologized. Said he was happy with his relationship back home in Belgium, gave me a long hug, asked what I was looking for.

“I have a boyfriend, actually,” I said in a flat tone. “We’re in an open relationship. He lives in France.”

“Ah. Interesting.”

A moment of silence as a pedestrian passed us on the sidewalk. I looked at my shoes and Lars twiddled his fingers.

“So, friends?” he asked eventually.

Friends was better than nothing. “Okay,” I said.

*

Reasons for desire blur into one another. Infatuation builds as quickly as male arousal.

Which of the following forms the best causal relationship to an all-consuming desire for an unattainable person: a) genuine adoration; b) titillation of the forbidden fruit; c) something to do with pride and rejection; d) all of the above?

I had no answers. All I knew was that Lars’ presence made the world feel vast, simple, and good. That he was everything I wasn’t: indiscriminately kind and slow to judge, unwaveringly positive and unbelievably free of self-doubt.

I knew that even when I looked at him under the unflattering fluorescent lights of a subway car, everything around him blurred away. I also knew that there was a voice in my head advising me to keep my distance, and that I didn’t heed it. We’re just friends, I told myself, just friends.

*

Lars came over for a movie one night. When I opened the door, he was standing in a royal-blue button-down of a satin-like material, and as we pulled away from each other after our greeting, it gleamed where the light hit it. It was fitted, and I could see the graceful slope of his chest and the streamlined curve of his deltoids.

Noticing my gaze, he said, “I had a meeting with a professor, and a presentation, so I said, bon, why not wear a chemise.”

In other words, he didn’t wear it for me.

Lars lowered himself into a chair, his movements slower than usual. He seemed low-spirited and tired, like circuits within him had been cut.

As I scurried around getting glasses and opening a bottle of wine, I felt his gaze following me, burning into my back when I stretched up to reach a shelf and felt my sweater lift to expose my waist, but I didn’t dare turn my head to verify. This was an anomalous moment. Lars only ever looked at my eyes; Lars was not interested; Lars was taken. Was Lars reconsidering now?

Lars is a human, I said to myself. I’m pretty, apparently. Humans like to look at pretty things. Nothing to dwell on here.

I asked him where he wanted to watch the movie. “Out here, or in my room?” Then I added, “I think my roommate is coming back soon.”

Not trying to precipitate anything; just stating a potential inconvenience.

“Your room, then,” he said.

Doesn’t mean anything; simply avoiding a potential inconvenience.

In the dim golden light of my bedroom, we sat on my bed, propped against pillows. The movie’s play button hovered on my laptop screen. As I reached out to press it, Lars asked suddenly, “Have you ever thought something was some way, when it in reality wasn’t?”

Indicator of fate, or sick game of hypotheticals?

“Of course,” I said. “Why do you ask?”

The inch of space between our knees seemed as wide and empty as an ocean trench—one that I had thought upon first meeting him that I could close so effortlessly, one that I never thought would weigh so heavily.

“I just mean… what we think is our reality crumbles so fast,” he said. “We assume things and it changes our perception but it’s all wrong the entire time.”

“Can’t say that hasn’t happened to me recently,” I said, hoping my tone was more teasing than self-pitying.

Then he was stretching out his arms and pulling me into his shoulder, and my head was resting against his neck, and I was thinking, Is this acceptably platonic? Is it out of sympathy or pity? I wanted to ask, What are you doing? but I didn’t know or care anymore, and if this was uncertainty, then it was an uncertainty I would happily rest in forever.

Soon, it was long past midnight. My computer lay on the ground, untouched. We spent the entire time talking, our movie abandoned. We talked about death, despair, and confirmation bias; sex, drugs, and Kant. We talked about everything except ourselves or our partners—Lars was this close yet Lars did not acknowledge it. I watched the ocean trench between our knees grow only wider as the night progressed.

At the end of the night, I walked Lars down to the street, where our goodbye was brief and chaste. I returned home to a message from Léo: I don’t want this to be open anymore. Okay, I thought, okay. There was nothing to be gained from its open state anyway.

*

You’d think that values and personality and history should, excluding wildly aberrant circumstances, predict most possible human action.

It was the end of the semester: the night before my flight to see Léo in France and three days before Lars’ flight home to Belgium.

I found myself in what started out resembling a bad romcom.

Lars came over to help me build a new bed.

By then I had agreed to Léo’s request to be exclusive again, and resigned to the fact that my relationship with Lars—now in its remaining hours—would never be anything but platonic; I’d gotten used to telling myself that circumstances which in any other context would signify romantic or sexual interest, between us meant nothing.

So screws were turned, planks were lifted, wine was drunk. Music—atmospheric and undulating—floated in the background of our last hours together. When we at last lowered the mattress on top of the frame, we looked at each other with wide eyes, like we had accomplished something triumphant.

“I hope it doesn’t creak,” I said, very serious.

“We’ll have to test it,” Lars said.

In one sweeping motion, he picked me up and tossed me on the bed. It didn’t make a sound.

He lay down beside me, his temple and wrist touching mine.

“It’s funny… the way attraction works.” Lars was looking at the ceiling.

“Yes,” I said, not sarcastic, though I wished I were. “Yes, it’s funny.” Then I added, “Why are you thinking about this?” scared to broach the subject but reminded by the flutter in my chest that fear and excitement are just two words for the same response in the hypothalamus.

“Je dirais… that I’m attracted only to my girlfriend.”

In the brief pause, there it was, that shattering sinking feeling. Why are you telling me this, I thought, I should throw you out of my bed. But there was the dirais, the would, that sneaky conditional.

He continued, “I think it’s no longer true. That time when we were supposed to watch the movie, that’s when our relationship—hers and mine—started to crumble. And now I’m not sure I still believe that there’s only space for one person in my heart.”

My arm found itself lying across his chest, my forehead against his chin.

“Yeah,” I said quietly. “I don’t know either.”

His hand on mine now, his thumb stroking my fingers.

What I’d been conditioned to think was so improbable a thing had happened so fast that I had to actively remind myself that it really was Lars’ body which was enlaced with mine.

Novel experiences create in the brain a rush of dopamine, a neurotransmitter best described as hedonism’s right-hand man.

Lars in this context was unfamiliar; having imagined him in my sheets didn’t make it less so. There was the rush, the novelty, the surprise, but mostly there was the realization of how far I had fallen down that godforsaken trench, looking up at his face haloed by the dim light, vacillating between concentration and tranquil contentedness. Riding along the waves of this realization was the regret that this would never be anything but novel.

The clock ticked.

Sprawled out against him on the beds, I asked, not quite expecting an answer, “Comment ça se fait qu’on s’est trouvés, but so late?” I meant mostly how did this happen, but how did we find each other sounded more poetic.

“I don’t know. But the night is young,” Lars said with a serene smile, but I heard the sadness in his voice.

And the night was young, as we talked, as our naked limbs entwined around each other, as if this was how it always would be.

And then the night was no longer young, and then it was over.

In the clarity of imminent departure, I tried hard to carve the moment into memory. The softness of our shadows on the pale yellow wall, our grey forms fusing then severing, fusing then severing. The grip of his hand on mine, my hand on his, the movement of our bodies synced with our breaths.

Our goodbye was quiet and stiff.

“À la prochaine,” he said, looking back before he descended the stairs. À la prochaine, à la prochaine. Certainly, there would be no next time.

*

Against the hum of the plane over the Atlantic, the distance between me and Léo shrinking with every hour, I played out arguments in my head to gauge the extent to which I was a bad person.

I donated monthly to the World Wide Fund for Nature. I quietly tipped my taxi drivers and baristas. I hadn’t eaten anything with a heart or brain in ten years. But sometimes I purchased plastic water bottles. And often, I forgot to smile at strangers.

Throughout my life, I had considered myself many bad things—unintelligent, unattractive, self-pitying, self-absorbed—but never a bad person. Maybe this is the end of it, I thought, as the plane hurtled to a stop on the runway of Charles de Gaulle airport, and my phone chimed with a text from Léo: I’m here 🙂.

*

A week after my arrival, Léo asked me if I wanted to go to Belgium for the weekend.

I hesitated.

“Maybe,” I told him. “Maybe.”

“You’ve been wanting to go for a while.”

It was true. I had always thought it was so outrageously close to Paris that there was no reason not to go. But now that the city was imbued with the connotation of a secret lover—or whatever Lars was—the prospect of being there sent me into a slight panic.

Should I see Lars? Would he want to see me? Was he still in his relationship? Would I want to see him if nothing were to happen? If I weren’t to see him, would I still want to go to Brussels?

Three days later, we were exiting Brussels-Midi station, my hand in Léo’s, walking past the frituur I was to meet Lars alone at the next day after Léo’s return to Paris for work.

*

When lust and longing intrude, it seems there’s no difference between memory and fantasy. Scenes lodged themselves into my head at inopportune times, when I was walking through alleyways holding Léo’s hand, or sipping beer across from him at noon, or watching his chest rise under the blanket. Sensations of Lars crept into the moment—his lips trailing down my neck, his hip bones rocking against mine, whether memory of New York or fantasy of Brussels, they intruded electric and charged.

At the train station on Sunday, Léo said playfully, “Don’t miss your train. And don’t let your friend pécho you!”

I had expected him to ask why I would want to stay an extra day in Belgium for a friend, to ask about how we met, to poke and prod. But there was nothing asked, only the look of serenity on his face as he gave me a kiss.

“I won’t, I won’t. He has a girlfriend,” I said, avoiding his eyes, guilt blossoming in my stomach like a limp, bleeding thing.

*

Two kisses on the cheeks never felt more platonic. Lars and I walked for hours through the winding streets of Brussels which, with their eclectic architectural styles and wider streets, were a welcome relief from the narrow homogeneity of Paris.

As we ate our andalouse sauce-coated frites on a bench and watched the city wake from its winter afternoon slumber, Lars recounted how his relationship, though still existent, was a vestige of its former self.

All I could say was, “I hope I didn’t interfere.”

“No, don’t worry,” he said, the familiar peaceful smile on his face. “The problems appeared way before you.”

*

With thirty minutes left to the departure of the train that would send me back to my boyfriend, Lars had me pressed against the corridor wall of the Airbnb building I had shared with Léo, one of his hands between my legs, the thumb of the other on my tongue, and I could taste the vague saltiness of the frites from four hours ago.

The clock ticked, and he, as the engineer, knew it better than I did.

“We’ll be quick,” he said in my ear.

“Où? Where?” I pulled my face away from his, asking, incredulous.

“Dans la chambre,” he said.

Chambre, I thought, quelle chambre? Which room? How?

“The keys are all hanging on the doors,” he added.

“Mais t’as pas une capote?” I asked.

“I do. I have one.”

Incredulous. I was incredulous. I was in disbelief and I was ecstatic as I climbed the stairs, my hand to my forehead, muttering, “Incroyable, absolument incroyable.”

He’s supposed to have a girlfriend, I thought. He’s supposed to have a girlfriend yet this morning while packing his bag he figured there was a possibility that we would be somewhere, here, entering an Airbnb room we didn’t book, throwing off our bags and coats in a frenzy, him tearing away my pants, his mouth hot on mine, the cold leather of the couch against my skin as he moved in me, we moved against each other, the sound of my breath sharp in the silent room, the back of his shirt balled under my hands as I felt the pulse in a place deep inside—as my eyes strained to reach his through the dark.

*

I caught my train by thirty seconds. We had run from one side of Brussels to the other. He’d taken my backpack, I his hand. It felt good—it felt like this was what desire drawn out over five months and two continents was supposed to culminate in: our coats flapping in the night, our fingers embodying the age-old metaphor of fitting like a puzzle. Consummation, avowal. Infidelity, I guess.

As he relayed to me, a margin of thirty seconds is a feat even for an engineer. For twenty-eight of them, we looked at each other through the window of the Thalys train, our chests heaving. I pressed my hand against the window’s frosted pane, my fingers spread out. Then I brought them against my lips, and extended my hand out in his direction. Was I really blowing him a kiss? I had never even done that with Léo. Last time I did it, I must’ve been five. What was I doing?

From the platform, Lars returned the kiss. The train was pulling out from the station. I was in one of those backward-facing seats, which meant I was pulling away from him. Soon he had disappeared behind the seat in front. His eyes never left me.

*

At home in Paris, Léo’s eyes lit up when I entered the room.

He kissed me; in a flash of fear I imagined him tasting on my lips those of another man. He didn’t. There was nothing to give anything away, to spur him into a rage against me that I deserved.

He sat me down on his legs, put his arms around my waist and rested his head against my neck—completely trusting, almost infantile—just glad to be in the presence of me. Me: wrong, philandering, unrecognizable me.

“Almost missed my train,” I said, teasingly, but a heaviness was forming in my chest. It was true, though. I had almost missed it because of Lars.

And I would have. I would’ve missed it to stay another few hours with Lars.

*

What’s worst is the ease with which I seem to have gotten away with it. In novels and movies, landmines are everywhere. An inopportune text on a phone, a coincidental run-in on the street, a misspoken name during sex.

Not here. Perfectly platonic messages, always a country of distance, precision with every direct address.

In bed, Léo took me in his arms, his cheek resting against mine.

“Comment ça se fait qu’on s’est trouvés?” he asked softly. How did we find each other?

I hesitated, no longer sure how to respond to this question that was neither new nor really looking for an answer.

“I don’t know,” I said, glad the proximity of our faces hid my expression from him. It was true though—I didn’t know how we had managed to find each other. I reached out and turned off the light, and darkness enveloped us. Soon, Léo’s breathing slowed and deepened, and I lay against him with my eyes squeezed tight, as if trying to shut the world out from us, as if trying to shield this person from the depravity of others, of me.

In the dark of the room, I thought about the way we will wake up to each other, the same way we have in the innumerous mornings over the past two years. How I’ll feel on my cheek a vague softness of his lips and the prickle of his beard, how I’ll hear his footsteps fade as he makes his way to the kitchen. I’ll hear the click of the kettle as he prepares the French press the way I like it, hear the jar of raspberry preserves pop open, smell the fragrance of his toasted brioche waft from him to me.

“Did you have a nice time in Belgium?” he will ask over coffee he has poured for me, over bread he has made for me.

I imagined nodding, rubbing my eyes so I wouldn’t have to look at him. I imagined coming back to this home again and again for another two years or more, dragging behind me a suitcase of guilt that smells of Lars and that grows heavier with each trip.

Then I imagined shaking my head before telling Léo the truth.

“I’m sorry. C’est toi que j’aime, I love you, it’s only ever been you,” I would say, concluding the confession. But could I still say that with certainty?

*

In the morning, I awake to coffee that Léo has poured and brioche that he made on Monday as the Thalys train shuttled me back to him from Lars.

“Hope you had a nice time in Belgium,” he says as I feel on my cheek the vague softness of his lips and the prickle of his beard. “I certainly did!” he adds.

I smile and bring my coffee cup up to my mouth, relieved that I wouldn’t have to respond. Across the table, Léo smiles back, and I remember how defeated he had seemed when I first met him, his lifeless eyes and messy beard, his features surrendered to gravity under the hanging grey sky of the Parisian winter. How in the past two years, home has changed from being a location to wherever he was—how we were always unsure about our future, but never able to separate.

“We saved each other, n’est-ce pas?” I used to say.

I blink dryly. What happened to that certainty?

“Si je revenais, on irait où?” I ask him. If I came back again, where would we go?

“Ira. On ira où?” he corrects me, using the simple future instead of the conditional. Where will we go when you come? “We’ll go wherever you want, as long as you come,” he says. “And why wouldn’t you?”

Here it is, Léo’s hope and commitment to our future sprawled out, simple and steadfast as grammar. He wants our future to be neither contingent on something nor hypothetical—he wants it to be unconditional. And I realize that there’s no version of the truth that wouldn’t destroy him.

*

That evening in the Airbnb, as Lars and I rushed to get dressed, I had asked, “If I came to Brussels again, would we see each other?”

I must’ve spoken too quietly, for there had been no reply, only the fumble of a zipper in the dark.

*

On the plane droning over the Atlantic back towards New York, taking me further and further from both Léo and Lars, the cabin feels like a coffin. A coffin filled with me and my lies—big lies, little lies.

In a wave of turbulence that rattles the plane, I clutch the armrest of my seat for want of a hand to hold. It is squared and hard, not comforting at all, and I think of the two pairs of hands I’ve held this past year, and I’m certain that I deserve neither.

I shut my eyes. Soon, I am asleep, and through the fog of semi-consciousness, I crack open my eyes to see a sea of clouds. It’s strangely quiet in the cabin; there’s the sound of water lapping. The turbulence has subsided to a rhythmic lull. This looks like Normandy; this looks like a memory. Sure enough, in the distance, half-buried in the clouds are two dark forms. It looks like Léo and I a year into the relationship, standing at the Northeastern-most coast of France, the diffuse white light of the sky forcing our eyes into slits. In this memory, I watch him: a small dark figure on the brown beach of winter’s low tide. “What a gift and a curse it is,” I think as he reaches down to greet the feeble waves, “to have someone who makes you afraid of dying.” Then a thousand sparkling objects bob up in the water—empty oysters and sea glass and glinting bottle shards of possibility and hypotheticals, none of which I had ever believed I was interested in. Yet I’ve left Léo on the shore and am wading deeper into the waves while reaching futilely for these shiny ocean fragments, until the sea floor gives out under me, I’m treading water and up to my nose in it, and Léo is nowhere to be seen.

With a jolt of the plane, the scene vanishes. As the engines roar and the intercoms blare and the plane hurtles down into New York, I ask myself of Léo, How did I manage to find you? How did I ever manage to find someone like you? Comment, comment ça se fait que je t’ai trouvé?

- Published in Issue 21

TWO POEMS by Hussain Ahmed

COSMOLOGY OF THE CLOUD WITH BABA AS THE RAIN MAKER

I.

The sky is a rolag, carded with grief and dew.

We were made in the image of our dead –

because God relies on recycling

to keep the earth going around the sun.

II.

Each of my father’s eye is a globe of brown worms,

or bulb of sperm cells swimming towards an egg in search for light.

He no longer reads the Qur’an without his glasses.

This ritual of whirling in the first rain has no origin story.

III.

Today, the sky looked freshly molded from clay,

I jumped inside the rain with my hands raised to the sky.

No one stays in it for long, so it doesn’t unmake the scars

on our heads – healing and almost forgotten.

IV.

The puddle sometimes gets large, it drags a child away.

Everyone lost to the water was recovered without their eyes,

that’s how I know that fish love to swallow whatever resembles a lamp.

ABECEDARIAN AS AN ATLAS FOR AWAKENING

Because my stomach is full of water, it means I thrive on what would kill me.

Cozenage of a dark room, full of pictures on transparent plastic films,

Designed on the sides with henna, they looked like postcards for men craving the sea.

Every child in this neighborhood learned to hold their breath under water,

For that is how we can survive the memories of the floods.

Growing on the corners of our room are honeysuckles – their fragrances

Herald the memories that kept us up in the nights.

I pretended to be asleep when Baba made for the sea,

Jaborandi leaves tucked beneath the sides of his ears, since it could not be

Knitted into a boat, to carry everyone whose names were etched on his rib bones.

Laying on the floor, I imagined he’ll be back before sunrise.

My body became a pool, rippled with the belch of a frilled shark.

Next time I make it to the beach, I hope to grow gills

On this chest that has been a cupboard for a burnt atlas, kept together with

Purl stiches, that now resembles the flag of a colony that no longer exist.

Quilts in different colors kept us from the cold and they

Remain an evidence for our hastily packed bags for departure,

Since no one noticed that we headed for the sea without knowing how to swim.

To speak of the dead is to make a pot from what should have remained clay

Under this pink sky – harbinger for awakened griefs, logged in stomachs, or

Vagary of prolonged drought, in a time when we needed the soil to break.

When the wind whistles, I sing along and drum the table that has the

Xylography of the past I don’t want buried on the beach. I continue to

Yearn for a flicker on the face of the Mediterranean, that will resemble

Zodiac sign, for how we may survive, unlike the men before us.

- Published in Issue 21

COME CORRECT by Erika Meitner & Traci Brimhall

If my lips are zipped—if I keep our delicious and contagious secret

—if I am amnesiac or too hungover to remember your mouth

on mine—if I forget the imprint of your body indelibly stamped—

if I search for you, call for you, lover, stranger, alien—if I offer up

gratitude to the air—if I rob you of your signals and energy (are you

battery-powered?)—if we fuck again and again all scorching night—

if we lock our power up to prevent a meltdown—if we twine ourselves

together like an interrobang—if we cross the imperial sea holding hands

or recycle our bodies into danger zones—if we do not yield—if I let you

come deep inside me (finally)—if we buy more time—if your body is a

snow-covered mountain—if your body is an emergency—if you sing

Karaoke (I will Survive? The Boxer?) under the stage lights at Tokyo Rose—

if our bodies become facsimiles or ghosts of themselves, like melted

snow or animal tracks—if you leave me—I need to say this, so listen:

if you go, do it quickly—the way a rabbit darts into the brush

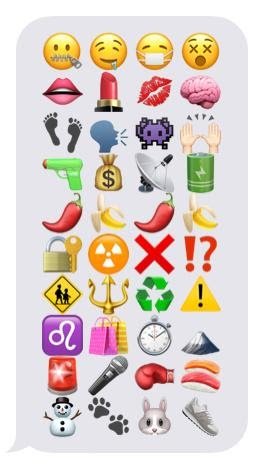

emoji poem by Traci Brimhall / ‘translation’ by Erika Meitner

- Published in Issue 21, Uncategorized

ANOTHER OHIO ROAD TRIP by Erika Meitner

First there were the Ten Commandments as tablets painted beneath One Nation Under God on the side of a semi container beached on the median

Then there were the faded billboards for Southern Xposure Gentleman’s Club and Jesus above it as if his body on a cross could cancel out all that glorious & oiled lady-flesh in the dark

Next, the bald brown mountain tops, their blunted domes crowning proud forested ranges

Stop ahead—keep right—all cars pay toll say the signs and the rumble strips every 100 feet

And when the road texture changes my younger son says, it sounds like submarines calling beneath the sea

West Virginia you don’t scare me

Not your metal flat-top bridge from one side to the other where the road cuts straight through rock & cliff faces stare at us blankly & the mountain tops are stripped bare—we drive under

Not your Lion’s Den Adult Superstore shouting Passion—Romance—Pleasure

Here’s the truth: last night we fucked on the living room couch but we were so drunk neither of us could come

Here’s the truth: I contemplated taking a topless selfie in the Bob Evans bathroom after lunch while thinking this ain’t the Hamptons because I’d been looking at too much Instagram

The Radio station fuzzed out every 10 miles

I want to be in God’s hands and reaching the unsafe with his mercy is what I thought the preacher on the Christian station said as I blew past him with the seek button

We passed a truck cab that said By His Grace in script on the back window

We passed piles of horse dung along the road’s shoulder—signs that bodies had run through, carried by animals with immediate needs

Fireworks and explosives do not mix well with alcohol, said Dr. Charles Sniderman in a 4th of July PSA about avoiding emergency rooms on another local radio station

New Pittsburg, Red Haw, all of Wayne County Ohio is being torn up by yellow diggers for the Utopia gas pipeline

Inspired by Gotye lyrics, my older son asks, How do you unknow someone?

Utopia cuts apart flat farmland marked with calf-high late corn and bales of hay leaving scarred earth, a giant furrow you could run through with a racecar

& the Amish teen boys on the road walking the shoulder in a pack, their black hats cocked—one lifted two fingers to me in a wave or salute & I waved back

I don’t take a photo of them with my phone, though they are beautiful in the way groups of similar things are, because it doesn’t feel right without their consent, so I post a photo instead of a barn painted with an Ohio Bicentennial sign (1803-2003) and a line of phone poles headed into the horizon

Do they ever get to escape? asks my older son about the Amish and I tell him about Rumspringa—that they’re set free from the community, but nearly all—ninety percent—return, and I’m not sure how I know that statistic but I know I’m right

I want to tell my son that it’s impossible to unknow someone—not even when the topography of their body changes, when there’s silence and more silence, when they try to erase themselves—not even when you choose to let them go

- Published in Issue 21

WHEN SUN SHINES ON WATER by Stella Lei

Claire goes pearl diving / in a swimming pool. Chlorinated and cold, / belly-down like a whale died / wrong. Claire is pallid, is sinking, / is alone, alone, alone. / Claire is halfway to drowned. Seeing through a haze / of blue, pickling her senses and watching the world / come apart. Cracks line the tiles / on the pool floor and she tries to fold / herself / into them so grout can sand / her clean, fresh. Claire is knuckling the whites from her eyes, / peeling cornea from iris from pupil / until only her retinas are exposed / to the sun. Claire wants to become lens flare, / wants to flash across photographs and screens. / Wants to blind. But Claire is shriveled, fingers on the edge of bloat, / in an empty pool. Claire is pretending / the bubbles are snapping lenses, / but her eyes are red and bleary / and her surroundings are swirled in fog. / The pool is not even her own—it belongs to a friend / of a friend who invited her over and is waiting for her to leave. / But Claire is bound to the promise of pearls, / of light, of fluorescence spilling over tile. Claire is staring at her face / in the grate, watching the metal warp / her features, / watching her eyes slide wide, blur / into her nose into her mouth. Claire is rubbing her fingers / across steel, touching her reflection, / trying to find her face.

- Published in Issue 21

GYM CRUSH by Josh Tvrdy

High-slit shorty short-shorts with a neon streak—

smooth scapulas the size of dinner-plates—

a sleeveless skin-

tight T-shirt that says, in cursive script, Sweat is just

pain leaving the body—yes, gym crush knows

how to snag the masochistic gays.

Gym crush could crush a can of Crush

against his forehead, easy. But don’t

get me wrong: he’s no mere beefy bod, no,

his beefy bod’s a beefy pod protecting his beefier brain.

For example: I overheard him say, Posterity! Micro-

aggression! They had no right to banish Galileo!

Damn right they had no right.

I’d like to lick his brain (I’ll bet he tastes like batteries).

In the sauna, gym crush grows

little jewels of sweat on his hairless shoulder.

When he leaves, his ass leaves

a sweat-heart on the wooden slats.

I’d like to be those wooden slats.

I’d like to be

his sweat-heart, sweetheart, sweet-tart, any part

he’ll let me play, I’ll play. His Axe

Body Spray? His week-old tube-socks souring his bag?

The skimpy towel he drapes over his shoulder, sash-like,

so confident in his bouncing junk,

daring me—the boy

who strips & dresses fast, as if the light burns—

to look? Yes. Yes. Once

I spotted gym crush perched

on the edge of a bench, a sledgehammer

dangling between his legs.

What does my handsy handyman do

with such a tool? Probably pounds

tractor tires, or slushes clusters of pumpkins, or punches

craters in the dew-slick grass to make me think

horses, happy horses were there in the night!

I’d like to be a happy horse in the night

(gym crush will ride me till morning).

But first he feeds me sugarcubes.

No, first he whispers hey boy,

then brushes my neck with the back of his hand.

- Published in Issue 21

ISSUE 21

POETRY

BECAUSE I MAKE MYSELF NEW EACH DAY by Rebecca Macijeski

AND WE TRY TO FIND GESTURES FOR OUR HUMANITY WHEN WE’RE YOUNG by Rodney Terich Leonard

THE HOUR OF THE WOLF by David Roderick

THREE POEMS by Sarina Romero

FIVE POEMS by Amorak Huey

TWO POEMS by Augusta Funk

TWO POEMS by Irène Mathieu

GYM CRUSH by Josh Tvrdy

WHEN SUN SHINES ON WATER by Stella Lei

ANOTHER OHIO ROAD TRIP by Erika Meitner

COME CORRECT by Erika Meitner & Traci Brimhall

TWO POEMS by Hussain Ahmed

FICTION

LOVE AND LEAVING IN THE CONDITIONAL by K-Yu Liu

EGG WISHES by Lucy Zhang

DON’T CALL ME YOUR PRINCESS by Megan Culhane Galbraith

AWAKE UNTIL DAWN by Pete Prokesch

ART

- Published in All Issues, Issue 21, Issues

TWO POEMS by Irène Mathieu

wish you were here

I want to try to tell you

about how lucid the water

was that day, how purposeful

the sun, how the wind

snapped a linen sheet open-

mouthed as a sail over

the railing at the end of

the pier – I wrote,

wish you were here

and meant it only

halfway through,

the line breaking off

and twisting at you,

my bare feet pointing

southward,

the soft and hard ocean

mewling so close I could

see the back of her

turquoise eye.

no one else can stand

in exactly the spot where

I’m standing, and

it’s taken three decades’ walking

to say I love you

to the inevitability of my solitude.

next to me

a man was coaxing his camera

into capturing this, like trying

to huddle fish together, their

silver bodies knives

slipping between his fingers.

we are always approximating –

see how the light changes just

before the shutter fires. I meant

to tell you I want to say that

this is as close

as we’re going to get:

I love. wish you.

a jellyfish is pulsing over

white sand six feet below my soles,

the photographer is angling to my right,

on my left a dark streak of coral,

and above my head a pelican, empty-

beaked, glints against a single cloud.

no one will ever be here again.

the line is scalloped and fleshy,

tastes of salt-rock. I suck it dry.

|

–we are witnessing a great age |

◊Love set sail centuries ago and I can still feel: 1) wind at my soles 2) salt spray on my teeth |

we made our (waterlogged) bed, now |

protects & strengthens skin’s moisture barrier up to 48 hours* |

|

I remember seeing the body of a sparrow in the parking lot of the narrow building where I did research one year |

capsaicin burn me brighter / brighter sharpen my song / along tongue-blade / solar flare me closer to |

lie your head on my bound wrists |

…wet & ringing I emerge from water onto land that has always known my name– |

|

I bow to sassafras cattail / fox darting in front of my headlights / petrochemical dawn / the marsh fog intoxicating almost to orgasm… |

*two suns later I’m sweating ceramides and safflower oil snapping my fingers counting backward◊ |

particleboard, fluorescence, neonicotinoids: this, too, is our inheritance. |

I don’t want don’t want don’t– |

(driftwood)

- Published in Issue 21

TWO POEMS by Augusta Funk

COUNTING TREES

The summer before you left

the store of wingbeats at dusk

finally broke off.

I reached for the shadow between the fence and the house

not caring if I looked plastic in the long stretch of green.

Once, measuring what was left of the earth’s

vertical fields, you almost called me lifelike.

It was a poor apology for a doll’s world at the end of the century.

But you made me imagine a crest of red rock both ways.

A sky too deep to see.

BLUE MACHINE

Days begin with fire. Logs husked of bark and kitchen tables piled with

glass figurines.

Lemons make the floor shine. The moon draws up the bottom of a cup.

I drop the bucket when the oven is warm. Soak the branches the older girls

cut from the oak.

They play while I supervise the younger ones at the stove. A quilt drapes

over a set of chairs. Separate rooms for love and snow falling easily.

- Published in Issue 21

- 1

- 2