INTERVIEW with AE HEE LEE

Ae Hee Lee is a Wisconsin-based poet whose debut collection, Asterism (Tupelo Press, 2024), was selected as the winner of the Dorset Prize by John Murillo. In Lee’s poems, heritage and belonging are examined rather than embraced. Visiting her father’s old home in Chungju, Korea, she asks the flowers growing there to “remember [her] from time to time.” Asterism travels through the three countries that have shaped her – Korea, Peru, and the US – chasing the spectres of all she has been and all she could have been. Her gift for sensual imagery is tempered by a relentless questioning of beauty and nostalgia. In a poem about the bureaucracy and anxiety of re-entry as an immigrant (“Chicago :: Re-entry Ritual”), she realizes that she must erase herself with each arrival, leaving room for “love, waiting/ at every side of a border.” In this interview, Lee discusses her journey in the literary world thus far, as well as the influences and concerns that drive her work.

FWR: I really resonated with the poems about the immigration process, the anxiety of going through border control, and the numerous hoops one has to jump through in one’s journey to secure visas and permanent residency. I am curious about how the language the immigration process subjects people to may have affected your own understanding of language.

AHL: Thank you so much for reading! I would say I’m glad you resonated with these poems, but at the same time, the immigration process, the anxiety, the paperwork, the money, and the hoops, can be so stressful that I don’t wish it on anyone.

I came to the U.S. as an international student to major in Literature and lived in the country with an F1 visa for almost 10 years, as I pursued grad school as well. I ended up meeting a person I could also call home here and applied for permanent residency, but I spent a big part of my adult life continually filling out and updating form after form to maintain my stay. This made me notice how the language of the immigration process and much of the political rhetoric around it stood directly in contrast with the language of literature and the arts that I had fallen in love with and had come to study.

In a sense, these experiences clarified for me the weight of language. Yes, there is language that seeks to control, hierarchize, and/or dehumanize, but there also exist languages that can resist the normalization of the former, reclaim, rehumanize, and love. So, I thought I wanted to be the kind of poet that strives to write in a language that is centered around such love and lives it out.

FWR: Food is a recurring theme and image in this collection — it becomes a vehicle for memory, tradition, and unconventional innovation, to name a few things. I am interested in whether and how food plays a role in your creative life today.

AHL: My mother used to say she liked watching me at the dinner table, because I looked happiest when I was eating. The act of eating, savoring and sharing meals, is something I find so much bliss in that any time I encounter a dish that is delicious beyond my expectations, I have the impulse to say “I love you” to whoever cooked it or is sitting with me. I also cook at home often – experimenting and trying out new foods, indulging in my curiosity about ingredients and tastes, inquiring about their journeys, their relationships with the hands that had made the dishes before me.

The way I experience food is not too different from my process for writing poetry, as I feel out the flavor and texture of each word I encounter outside or within the context of a line, and seek to learn about and from them. Since I was a kid, I kept a notepad with Korean, Spanish, and English words that I was fond of because of how they sounded or were interesting to me conceptually. But I would say food brings me a joy that feels more instinctual and immediate, while poetry is slower, and denser.

FWR: There are a plethora of forms used in Asterism. I am always interested in hearing writers talk about their process at a granular level. Would you tell us a little about how you chose the form for the poem “NATURALIZATION :: MIGRATION”?

AHL: When I write, I tend to have my poems lead me, and form is one of the things that the poem itself will make clear for me while drafting.

“NATURALIZATION :: MIGRATION” came to me at a pottery sale organized by college students. For this poem it felt right to be faithful to the sequence of thoughts and actions of the moment: to start with being present in the location, buying nothing, then move back to past instances of movement, to finally come to a reinterpretation of the word “naturalization,” hence the title.

“Naturalization” has always struck me as a strange word. While it’s largely defined as the legal process by which a foreigner becomes a citizen of a country, it also carries the implication of assimilation and a kind of belonging that is fixed and exclusive. This all feels at odds with how every living being exists in nature, always in movement, even when seemingly in the same place (the progression of plant roots, for instance).

While admiring one of the vases, I went back and forth between the urge to possess an inert object that made me feel grounded, the yearning to subscribe to the illusion of a “permanent” home, the thought I was not a vase person, and the consideration that I love and want to embrace the wanderer and wandering in me. And so, I felt the poem move too, which is why we arrived at a form resembling a river, the undulation of squirrels.

FWR: Do you remember when you came across the word “asterism”? And would you talk about why you chose that as the title of your book?

AHL: I confess I don’t recall the exact moment, since I often find many words by going down rabbit holes. What I do remember though is thinking how “constellation” didn’t feel quite right. A constellation is an officially acknowledged group of stars. In contrast, an asterism is a pattern or group of stars that can be observed by the naked eye. I didn’t grow up with a knowledge of constellations, but like many other people, I have stared at the stars and connected the shining dots to form figures of my own.

“Asterism” felt like it offered a more intimate relationship with the sky, and by extension, the world, and I realized the manuscript was just that. I came to understand the poems as a collection of patterns, personal and collective meaning-making, that arose from living in and reflecting the different countries and cultures I lived with.

That said, I also liked how asterism could mean a group of three asterisks (⁂), which is a symbol used to draw attention to following text, and that it brings to mind a field of aster flowers.

FWR: You’ve had three chapbooks come out in the past. What was that experience like? Did it help you find your readers?

AHL: I ended up with three chapbooks before turning to focus on finishing my first full length, because I often find myself jumping around projects. The result was Bedtime // Riverbed, Dear Bear, and Connotary, which are vastly different from each other; the first consists of Korean folk retellings rippling with “Hanja,” the second is a postapocalyptic epistolary romance, and the third is the chapbook that became the backbone for Asterism.

A backbone in itself is quite complex and beautiful, but with Connotary I started seeing a full body of work forming around it. While I can’t say for sure if I was consciously looking to build myself a platform, putting Connotary together gave me a more lucid idea of who at the moment I wanted to reach the most. Therefore, my hope for Asterism became that it may resonate with anyone who needs to hear that polycentric and transnational lives have a place in this world.

FWR: There are moments in Asterism where you appear to move very deliberately away from sentimentality. The endings of “GREEN CARD :: EVIDENCE OF ADEQUATE MEANS OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT” and “EL MILAGRO :: EDGES” come to mind. How did you arrive at the endings of these poems?

AHL: This is such an interesting question!

I confess there’s a bunch of cynicism in me that I fight against daily. A friend once shared that she mainly had a child leading her heart and an occasional elderly man that sometimes popped his head out to say something grumpy. In contrast, I would say I am mainly a grumpy old woman, but there’s a small poet inside that keeps murmuring “but…”

Even as a child, I felt rather unsatisfied with any perfectly-happily-ever-after I encountered in books. I do enjoy a good happy ending, but I’m suspicious of the perfectly-happily-ever-after, the insinuation that such an ending could legitimize and do away with all the struggles the characters had to go through. I think this translated into some of my poems, particularly the two you have mentioned. I won’t say too much about their endings so as to not impose my own interpretations into anyone’s reading of them, but for “GREEN CARD :: EVIDENCE OF ADEQUATE MEANS OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT” I sought to avoid certainty. For “EL MILAGRO :: EDGES” I thought to address the impossible prospect of fully understanding another’s experience.

The world is messy, and sometimes this can be cause for wonder, but I also simply wanted to acknowledge the very real feelings of resignation, helplessness, and loneliness that we experience as human beings dwelling in what seem like perpetually broken systems. Sometimes these emotions do feel like the end. However, I also like to think the very act of writing in the poetic language is a resistance against letting that “end” have the final word. For me, this apparent contradiction leaves itself open to the possibility of continuation, and hope.

Like yes, “What else could I do?” But… Here I am, writing. Yes, “It’s hard / and not so sweet.” But…!

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview

INTERVIEW with ROBIN LAMER RAHIJA

Robin LaMer Rahija‘s first full length collection, Inside Out Egg, was released in April. Ada Limón writes that “each poem contains the whole unbound strangeness of the human experience–the offhand remark, the blur of being in a body– all of this is written with a humility and understated wit that both growls and sings….” We were thrilled to interview Rahija about her process in crafting Inside Out Egg, as well as the development of this collection’s voice and the nature of the absurd– both in poetry and in the world around us.

FWR: Your poems conduct us into a theater of the absurd where you satirize our fears, our peculiar tendencies and our most ridiculous but touching attitudes. Your voice rings with audacity, and performance, as well as rebellion. When you say, “Something just feels wrong”— about our culture, our lives today, our attempts to find each other, the reader believes you. But, the tender, humorous way your poems express both the wrong and the small touches of “right” give us, your readers, both pleasure and hope in finding community.

I’m fascinated by the short poems that you’ve interspersed in your text that raise mind-boggling questions like “who’s to blame for this bad dream” and comment on the many uses of the preposition “for.” Did you conceive of them as breaks or respites, or did you have other thoughts about their place and placement in your book?

RR: Do you mean the Breaking News poems? The Breaking News poems I thought of as interruptions, like when we’re having a meaningful interaction with someone and the news app on the phone pings with something insignificant, or significant and horrifying, or stressful, and then the moment is gone. I wanted them heavy in the beginning and then to fade away as the book sort of settles into itself and the voice becomes more focused.

FWR: I think many writers and readers, including me, are interested in questions of process. Would you tell us a bit about your process—how a poem begins for you, if there are recognizable triggers; how you develop that initial impulse; how you revise, and so on.

RR: I think about this a lot. It might be different for every poet. It seems like magic every time it happens. Often it’s phonic. I’ll hear a phrase that sounds cool, and it will get stuck in my head like a song lyric. A friend of my told me a story about seeing a fox on the tarmac as they got on a plane, and I’ve been trying to work the phrase “tarmac fox” into a poem ever since. Other times it’s more about just noticing language doing something weird. I was watching the Derby the other day and a list of the horse names came up, which are always ridiculous: Mystik Dan, Catching Freedom, Domestic Product, Society Man. So now I’m thinking about a list poem of fake horse names, or what they’d name themselves, or what they’d name their humans if they raced humans for fun. The trick is training yourself to notice those moments, and also to note them down and not just ignore them.

FWR: Also, to my ear, you have a very strong, confident, even outspoken voice in your poems. One example that caught my ear is your title, “I Can Never Put a Bird in a Poem Because My Name is Robin” and “That Is Not Fair That” voice, to my ear, is quite brave, as well as funny. How did you develop that voice, or was it always natural to you?

RR: No, it’s definitely not my nature. I had to write my way into this voice. I started out writing language poetry that was just pretty sounds with no meaning. I was avoiding writing (and thinking about) the hard things. Writing for me has been a lot of chipping away at my own walls. Each poem too I think has to work on becoming that confident through revision. I don’t want my poems to be complaints. I want them to reveal something, but it can be a fine line. I’m a jangly bag of anxiety most of the time, and I think my poems reflect that. Writing is an attempt to make the jangles into more of a coherent song.

The humor is mostly accidental, I think. Or maybe it comes from an inability to take myself seriously. I do want to get the full range of human emotions out of poetry, and humor is a big part of how we get through the day.

FWR: Who are you reading now? And are the poets you read representative of anything you would describe as “contemporary”? Is there such a thing now? I’m thinking of Stephanie Burt’s essay describing recent poetry as “elliptical,“ meaning the poems depend on “[f]ragmentation, jumpiness, audacity; performance, grammatical oddity; rebellion, voice, some measure of closure.” Does any of this ring bells for you?

RR: I haven’t read that but it feels true for my work. I’m reading Indeterminate Inflorescence by Lee Seong-bok from Sublunary Editions right now. It’s a great collection of small snippets, like poetry aphorisms, that his students collected from his classes. I don’t know how I’d describe contemporary poetry, except it feels brutally personal and outwardly social at the same time.

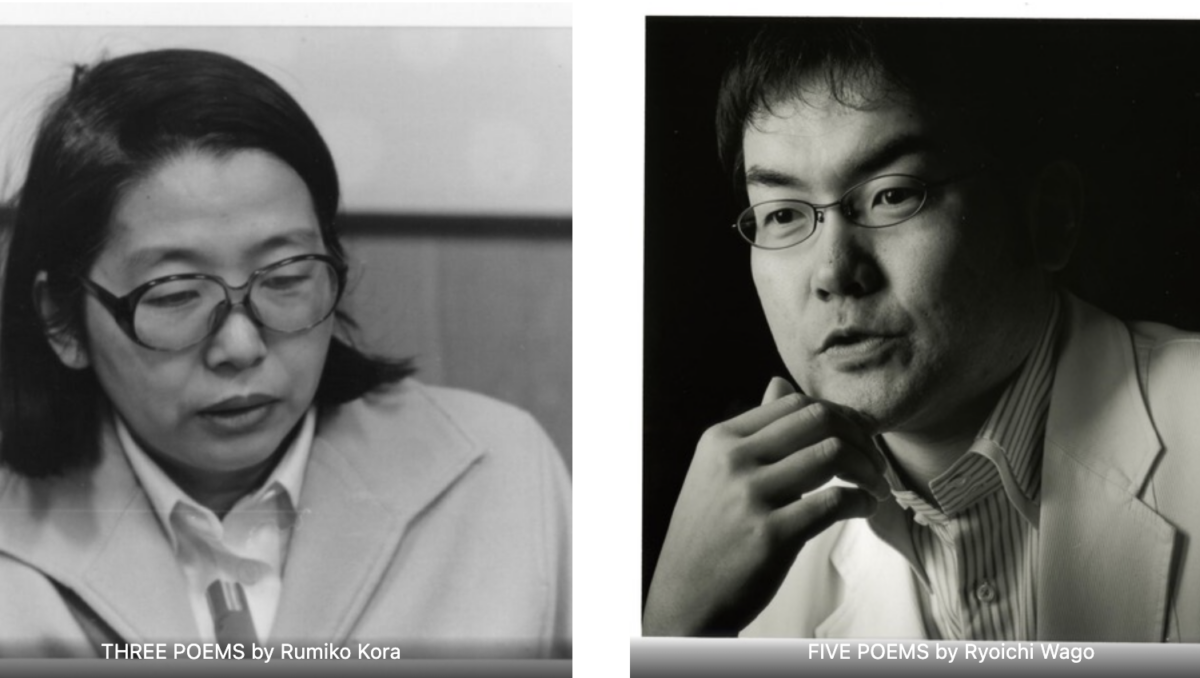

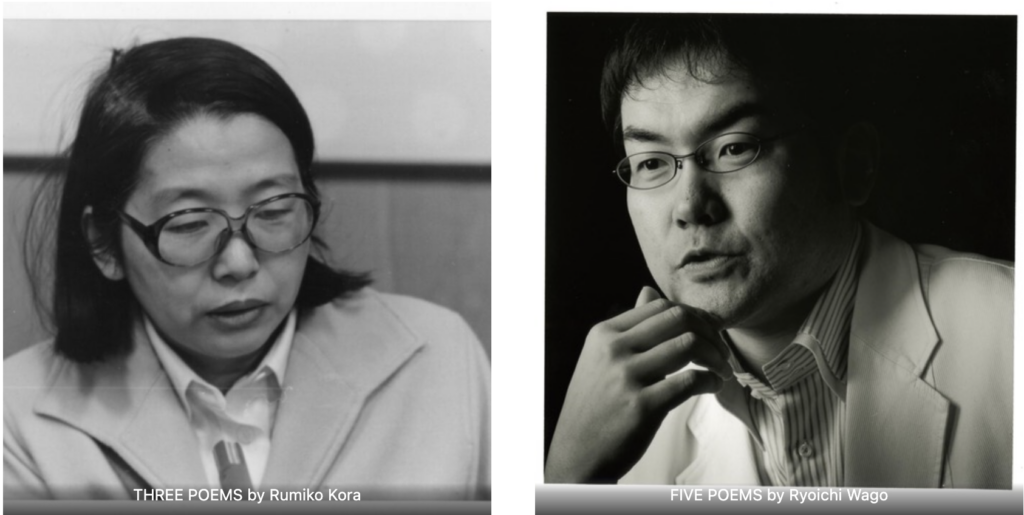

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FIVE POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

This folio shares recent translations from two Japanese poets, Kora Rumiko (1932-2021) and Wago Ryoichi (1968-). Kora’s poems are from the second half and 20th century, and Wago’s were written following the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown that devastated his home region. Writing in different times and from different perspectives, these poets overlap in that their writing draws attention to environmental degradation and inequality while simultaneously voicing a strong sense of place.

Kora was born and raised in Tokyo. Her childhood was shaped by the Second World War and the devastation of the Tokyo fire bombings that she witnessed as a thirteen-year-old. In the changes of the post-war era and the rapid industrialization of the 1970s, her neighborhood grew from a small community to a bustling urban area. Her writing speaks against capitalism and colonialism. At a time when many Japanese writers were influenced by European literary forms, Kora looked toward writers from Asia and Africa, all while drawing inspiration from mythology, envisioning matriarchy, and speaking to the harms and costs of nuclear weapons and nuclear power.

These themes are evident in her poem, A Mother Speaks, which is set within the Noh play A Killing Stone (Sesshôseki). Noh is a somber, serious theatre tradition that has been in living practice for more than six hundred years. Plays often have themes of connecting the dead with the living and of vanquishing evil spirits. A Killing Stone references the legend of the fox spirit and Lady Tamamo’s attempt to use her supernatural power to kill the emperor. As the story goes, her plans fails and her spirit is relegated to a stone that kills any living thing that passes over it. Kora’s poem envisions Tamamo’s power, fertility, and the potential of transformation, offering an embodied, feminist perspective on the Noh play and the legend more broadly.

Wago is a high school teacher and has lived in Fukushima prefecture his whole life. In March 2011, when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear powerplant failed, he did not evacuate, but sheltered in place in his apartment in Fukushima City, 50 miles away from the powerplant. He started a Twitter feed of thoughts and observations, which soon had thousands of followers. Pebbles of Poetry 1, from Macrh 16, 2011, marks the very beginning of his posts and the moment when people were just becoming aware of the radiation leaks. On several occasions, Wago visited areas inside the evacuation zone, a 12-mile radius of the power plant. He wore a protective suit and a radiation monitor. His poem Screening Time was written after one of those visits. Wago’s writing addresses environmental degradation with an ecopoetics that not only explores the human toll of this catastrophe, but also includes the perspectives of cows abandoned in the fields; the fruits and crops left to waste; the once vibrant towns that now stand empty; and the soil, the ocean, and the air.

January 7, 2021, is one of a series of poems that Wago wrote marking ten years since the nuclear meltdown. It voices a more composed perspective on the memories and experiences of his earlier writings. It opens with a description of flying above the evacuation zone and includes a conversation with a dairy farmer forced to evacuate the area and abandon his herd. The poem integrates quotes from Wago’s twitter feed on March 22, 2011 in the first days following the meltdown; contextualizing, in this way, the original posts, integrating them with images and details to create an immersive sense of presence. Much of Wago’s work is dedicated to restoring Fukushima prefecture, not just in terms of environmental restoration, but also of the culture and lifestyle of the region and the well-being of future generations.

Ayako Takahashi and I have translated these poems collaboratively, working together weekly over video chat since 2017. Ayako tends to favor a more literal translation, while I am often most concerned that the translations work as poems. Our hope is that we have landed someplace in the middle, maintaining with fidelity the vitality of the original works.

- Published in Interview, Monthly, Translation

MONTHLY with Alexander Duringer

Alexander Duringer is from Buffalo, NY and earned his MFA in Poetry from North Carolina State University. He is a winner of the American Academy of Poets Prize as well as the Bruce & Marjorie Petesch Award. In 2022 he was a finalist for The Sewanee Review’s annual poetry contest. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Plainsongs, Cola Literary Review, The Seventh Wave, The Shore, and Poets.org. He is interviewed for Four Way Review by Matthew Tuckner.

FOUR POEMS by Alexander Duringer

INTERVIEW WITH Alexander Duringer

INTERVIEW WITH Alexander Duringer

Alexander Duringer is from Buffalo, NY and earned his MFA in Poetry from North Carolina State University. He is a winner of the American Academy of Poets Prize as well as the Bruce & Marjorie Petesch Award. In 2022 he was a finalist for The Sewanee Review’s annual poetry contest. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Plainsongs, Cola Literary Review, The Seventh Wave, The Shore, and Poets.org. He is interviewed for Four Way Review by Matthew Tuckner.

FWR: I thought I would begin by asking about the role of image in your work. I often find myself thinking about the comparison of the prostate to a “little tyrant, Caligula/at war with the Tyrrhenian Sea/astride his senator horse,” or how the “curved neck of a blue heron,” in the “The Poet,” becomes a “question mark.” Considering the many startling images in these poems that are awash with the particulars of queer subjectivity, I am reminded of a quote from José Esteban Muñoz’s essay “Ephemera as Evidence” where he writes that “ephemera,” as an aesthetic mode, “is always about specificity and resisting dominant systems of aesthetic and institutional classification.” Does this definition of “ephemera” as a mode of queer image-making speak to your process in any way? How do you know when you’ve arrived at the proper expression of an image?

AD: Ah, thanks so much for such kind attention to my poems. I love this line of thinking.

Muñoz’s work is always close by as I write—particularly his thinking on utopia. Lately I’ve become interested in the ways that image—but specifically metaphor—can cascade, layer, and like a line, break into something new. I think a lot about the ways that I use metaphor/image to arrive at something that is perhaps truer than what is (at least initially) perceived? Though “true” might be the wrong word, because I think metaphors are inevitably inaccurate. I’m thinking here of a poem by Natalie Diaz called “I Watch Her Eat the Apple” where the apple held by the beloved begins as a merry-go-round spinning in her hands and ends as a bomb. The apple itself never really changes (though of course it’s consumed) but the meaning associated with it evolves from this site of childhood joy to something sinister and dangerous as it’s manipulated by the partner and observed by the speaker until the speaker herself becomes a kind of apple that will be eaten and tossed away by the beloved.

I don’t know that I was consciously thinking of Diaz when I wrote “The Prostate,” but looking at it now, I see some definite parallels. The prostate, like the apple, matters much less than the person it’s related to, and I’m interested in these shifting/varied perspectives around a subject. In many ways the prostate is an absurdity, an odd little organ that can do immense damage to a human if isn’t caught in time, but it’s also a site of pleasure and it was important to me to capture these various, conflicting, truths. It begins as a walnut and ends as something precious. It expands, it takes up space. It induces fear in men and yet it’s never really visible—it exists as a site of pure feeling. I wanted to get to this sense of affect while interrogating the ways in which this site of pleasure in the human body is often relegated to the realm of danger, something to be observed with suspicion and potentially destroyed. The image, then, is dictated by the emotional resonance around the subject matter which I think must inevitably change to arrive at the specific (to pivot back to Muńoz) vibe that the poem demands.

I’ll know that I’ve landed on the right image or image system when it resonates emotionally (and/or specifically) in the ways that I associate. “The Poet” is a violent poem and the question that the speaker refuses to ask is a violent, strange one that demands an image which will lead the reader to that since I intentionally left the question unasked. My goal with that image was to give a clue into nature of the speaker (a shift from the third-person Poet who was in control through the majority of the poem) and the question he was asking without making it completely obvious, while also highlighting the distinction between omnipotent Poet and poem’s actual speaker, who identifies more with prey than with the hunter.

The image is able to extend beyond itself into a sort of scene where the heron’s neck becomes a site of violence, moving into the shape of a question mark so that it might skewer its dinner.

FWR: I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the ars poetic impulse in your work. These four poems all have moments that point to the poem as a tool for discovering the proper language for a certain experience. Despite the direct references to “writing” in poems like “The Poet” and “The Queer’s Epithalamium,” the other two poems also seem to gesture towards the fact of their genre implicitly. In “The Prostate,” “mouths and tongues formed new vowels.” At the end of “The night breeze so clear &,” the speaker can’t help but exclaim “Jesus christ, so many lines,” upon seeing the tangled bodies of fallen kites. How much of writing poetry for you is about working through what writing a poem actually means, what it leaves out, what it can capaciously include?

AD: This has been an essential question of the project that I started working on in my MFA and grew from many of the experiences I had there. I’m very interested in the ways that the mind works and how it works through and within things like grief and desire and fear and rage. For me this “working through” is done via writing and so I think it was inevitable that many of my poems would confront/contemplate the act of writing which, for me, is often simultaneous with thinking. The act of writing makes facets of my identity (or perhaps merely my stance) much clearer to me and yet I often feel exasperated with myself because I feel as though the only way I can approach events in my life with any authenticity is by writing, and therefore looking backward, rather than experiencing things in the present. It’s true that a poem allows me to confront, as well as interrogate my emotions with a kind of precision charged by inquiry as in “The Queer’s Epithalamium” and “The Prostate,” but I sometimes wonder if I’m losing out on opportunities in the present.

This impulse didn’t really begin until after my mother died three and a half years ago when my grief felt insurmountable and the distance that writing demands became a kind of coping. Her death spurred me into applying for an MFA after working for five years as an English teacher and in my last year teaching high school, I worked for about ten months developing a packet after ten years of writing almost nothing at all. When I got into my MFA (totally by the skin of my teeth), I was self-conscious of my stance as a writer and felt like a fraud, so I spent a lot of time learning and relearning the “basics”, which I grappled with in poems of my own. These haven’t really been seen by anyone and are largely just learning tools for myself because I process my thoughts better through writing (indeed, this very interview has helped me understand myself and my inclinations more than I had before). The work therefore became cyclical in that I wrote to learn and was learning to write. Regarding my mother’s death, I often try to create distance between myself and the subject matter, as in “night breeze” in which I recognize the impulse in myself to poeticize everything and feel frustrated by it. Thinking in this way helps me consider these events without going crazy with grief, but it’s totally a form of disassociation and sometimes I’d like to allow myself to lose control.

In my MFA, I often felt inclined to write things that felt morally questionable for me later (for example, I wrote image after image about my mother’s death bed and corpse, specifically her mouth) and one of the projects I set for myself was to grapple with and problematize those inclinations. I regret and reject these drafts now and wouldn’t ever try to publish them, but I needed to work through those things to better understand what I think is and isn’t acceptable in a poem of my own. During this same period, I was reading poems that made me deeply uncomfortable from a political and ethical standpoint. Without going into too much detail, they seemed interested mostly in shocking for the sake of it and were often violent toward targeted groups of people without considering the stakes of that violence. I usually wrote pointed responses that (despite my anger and frustration) helped me to develop a sort of rubric for my own about what was and wasn’t acceptable in a poem, at least one that was written by me. This led to “The Poet”, which is meant to confront these violent inclinations of my own and others from the perspective of a speaker who is essentially without control over his own body.

FWR: In her poem “Celestial Music,” the late Louise Glück writes that “the love of form is a love of endings.” I know, from our previous conversations, that the sonnet crown is of a particular interest to you in your writing practice. Thinking now of Glück’s assertion, it occurs to me that the sonnet crown hinges on “endings” as both destinations and beginnings–continual closings and openings. What does the sonnet, as a form, afford you as a writer? Does Glück’s equating of form with finality gel with your own feelings about form?

AD: The true sonnet crown with the fifteenth master sonnet made up of the fourteen preceding first lines embodies both beginnings and endings and I’ve always thought of the crown as a kind of ouroboros—the snake eating its own tail. It’s a closed circle, sure, but one that continues forever. One way I like to think of the sonnet as a unit (and this isn’t unique to me, of course) is that of a box. The box has to close and the poem must end, but the knowledge of that imminence fills the space with a kind of desperate charge that is tempered by the writer’s control. And when I sit down to write [a sonnet], I’m inevitably thinking about how to get to that point of closure, but honestly I’m drawn much more to the site of rupture embodied by the volta, which makes the box sizzle at its edges from this potential for change.

An important function of the sonnet for me is what Carl Phillips has described as its “capacity for innovation.” He describes this via innovations of form as well as content. A queer writer queers the sonnet by writing about queer experiences, but he can also do this via disruption of form, which I obviously did in “The Queer’s Epithalamium” [and] which is an intentionally failed sonnet. It’s only thirteen lines and two of them appear to be sliced in half. When I wrote it, I was thinking a lot about marriage and the arbitrariness of the rules we impose on ourselves, and I wanted to resist that. It’s probably a bit obvious, but I thought the sonnet—in this instance—with all its understood conventions complimented the normative wedding of the speaker’s friend. I became interested in using the broken/failed sonnet as a kind of structural representation of the cracks in the wedding’s façade, which amplify line by line beginning with the first image of the “broken swan’s neck” and ends with [the] ambiguous final line. But again, the poem’s volta is the true darling of the piece, so much so that I gave this one two: the first, where it’s conventionally meant to occur with the shift to the invocation of the speaker’s boyfriend and the second (what I think of as the ‘true’ volta), at the word “faggot”, which is meant to create a sense of whiplash in the reader as the subtextual violence queer people are made to endure at these kinds of events is dragged to the forefront. For the poem then to end a line early might imply a desire for finality or closure, but my true goal there was to try and live in the volta. The poem ends on a period, but it could just as much end on a dash (and actually, maybe it should) and leave the reader with even less closure than it currently does.

FWR: Lastly, I’d love to hear a little bit about your writing process, both generally and specifically in terms of these four poems. Do you remember the drafting process of these poems? How did they arrive at their final forms?

AD: My writing process is pretty scattered. Often I’ll begin with a project in mind—whether it’s a group of poems like a sonnet crown or an idea for an individual poem. Much of my poems are based (at least initially) in memory so I’ll try to get my thoughts on/from a specific event onto the page. This phase is very diaristic but gives me a foundation to work from as I start to lineate and make things weird. This is a frustrating process because the results always look like failure and the poems are usually eventually placed into a large document with its siblings. When I go back to that document I’ll try to move lines around from one to another and make them cannibalize each other.

This is nodded toward in “The Poet” which, as you mentioned in an earlier question, is very much an ars poetica centered around my frustrations with this process. That poem began as a much shorter piece with a different title and different beginning and was nowhere near complete. I might have showed it to three people who were like, “uh-huh,” and then I left it alone for a year or so in that large document. Then I began to work on a series (also failed, also tucked away) of poems about Antinous (the famously drowned/sacrificed paramour of the Roman emperor Hadrian). I was interested in the idea of control in relation to this young man whose life, I was arguing, was lived in service to the epitome of power and only achieved control over his own life in death, but there I was playing with him like a kind of doll. It made me uncomfortable and I could tell that the project wasn’t working, so I started moving things around. Some lines from this Antinous poem merged with lines from the earlier one and became an early draft of “The Poet”, which is much more about myself and the frustrations I feel while writing.

“The Prostate” and “The night breeze” are kind of unique for me in that they haven’t changed a whole lot since I first wrote them. Or at least nothing very dramatic has happened to their language/shapes. The latter is one of the few poems I’ve written that I don’t think has ever changed beyond a word or two. I’d been awake at night in Raleigh thinking about my parents and it just sort of happened that I reached for my computer and got to work. I might have moved some things around, but overall, it really was a kind of one-and-done poem. I wish that happened more often for me.

I’ll often change where lines are broken in “The Prostate” because I can never agree with myself on what works better. I’m so happy that that one’s been picked up by Four Way so that I can stop tinkering with it for a bit. One large edit I remember making in the tenth draft or so involved the positionality of the speaker at the end. He was originally dominant with his lover and that became frustrating for me since the poem is so much about admitting to vulnerability. I felt like this speaker needed to be the one whose body was vulnerable to demonstrate the changes that have occurred within his mind. It made the poem less about the titular organ and more about the speaker’s understanding of himself.

- Published in Interview

INTERVIEW WITH Jared Harél by Urvashi Bahuguna

Jared Harel’s poems are quiet records of the layers inside the ordinary days of our lives, exposing the restless forces and memories that power and threaten our most mundane actions. In “Behind The Painted Railguard,” the poet is standing in an amusement park with his mother, watching his young son on a ride. He uses that particular scene to reflect on the past, expectations, family lore, acceptance, difficult silences – the breadth of what he covers is a testament to Harel’s relationship to craft. His crisp lines and clear, effective imagery accompany us throughout his second collection, Let Our Bodies Change The Subject (University of Nebraska Press, September 2023), as we move through poems that are anchored in themes of parenting, marriage, and family, and that contend with the inherent pain of being alive. Harel has won multiple awards for his writing including the Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize, the William Matthews Poetry Prize, Diode Editions Book Award, and 2022 Raz/Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry. He lives with his family in Westchester, NY.

FWR: The collection’s opening and closing poems really appear to speak to one another. I love that we begin with a child trying to puzzle out death and end with a child who has learnt that the world is less magical than they first believed. Were you conscious of that implied journey as you ordered the poems? What is your process when it comes to ordering a manuscript?

JH: First off, thank you for taking the time to dig into my new collection! I knew I wanted to open the book with “Sad Rollercoaster” as an introduction to themes of parenthood, mortality, NYC and more. My decision to end on “Dolls Can’t Talk” took longer to figure out.

When giving shape to a poetry manuscript, my process is to print the poems and spread them out on my kitchen floor. Certain poems I know I want close together, while others I want to keep apart. Then I pay particular attention to the beginnings and endings of poems. For instance, does the closing line of ‘Poem A’ link well or create an interesting friction with the opening line of ‘Poem B’? Kinda like train cars. Then I trust this momentum to carry the reader forth.

On a larger scale, beginning the collection with the line, “My daughter is in the kitchen, working out death” then ending, “How long have you suspected/we might be alone?” felt like the right arc and tension for this book.

FWR: As I read and re-read the book, I had this overwhelming sense of witnessing deep love. As someone who writes about central relationships in her life as well, I would love to hear about how you navigate writing about the relationships in this book. How does the personal affect your craft or the lens you choose to turn upon these subjects?

JH: Honestly, I try not to worry about this too much when making poems. My goal is to write the best poem I can—something that feels true and conveys both a passion for language and the experience behind the words. I’ve often been asked about the decision to include my children in my poems. The truth is, I don’t know how to keep them out. Sometimes I’ll be writing and my son will literally leap onto my lap. If I’m interested in writing poems from a genuine place, these people who give shape and meaning to my life (my kids, parents, siblings, friends, spouse) will continue, I imagine, to appear organically in my work.

That being said, I do think there’s a difference between writing poems and the public decision to publish them. There’s one poem from my first collection, Go Because I Love You, which I kinda regret putting in the book. It’s one about my parents, and while I think it’s a strong poem, I’m no longer sure it was my place to publish it.

FWR: “You Want It Darker (2016)” also appeared, if I am not mistaken, in a previous collection. The choice to include it again intrigues me. What brought that about? (I apologize if I am mistaken.)

JH: Good catch! You are not mistaken. I wrote “You Want It Darker” in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Those were dark days made darker by the fact that Leonard Cohen passed away that very same week. In my poem, I aimed to articulate a collective, community-wide grief I felt around Queens, NY at the time.

Years later, I drafted a new poem in the hours leading up to the 2021 Presidential Inauguration, and titled it simply “January 20, 2021.” That poem felt like a long-awaited exhale and a bookend to “You Want It Darker.” For that reason, it made sense for me to include both poems, one after the other, in this new collection.

To my delight, “January 20, 2021” was the Academy of American Poets ‘Poem-a-Day’ on January 20, 2022, exactly one year after it was written. In any case, fingers crossed there’s no third poem to this series!

FWR: “Our Wedding” is one of my favorite poems from this collection. I am so curious about the genesis of it. Is the speaker many years removed from the event? Why did the poem come to the poet now? Or is it something they have been working on for a long time?

JH: By the time I wrote “Our Wedding,” my wife and I had been married for 11 years, so it certainly wasn’t written on the heels of the event. Actually, we’d just attended my cousin’s wedding, which got us thinking about our own ceremony and party, how young we’d been, and how today – as “proper adults” – we’d do things differently. That opening couplet, “It wasn’t what we wanted,/but we wanted each other” hit me the next morning, and the poem developed from there.

FWR: You’re a drummer. What does that bring to your life?

JH: I’m drawn to the social and collaborative aspects of being a drummer in a rock band. My bandmates and I write songs and play music together, which is totally different from the solitary act of making poems.

Thinking about similarities though, there’s definitely the element of rhythm to both. Whether writing or drumming, I’m driven by cadence and beat. When revising, I’ll read and re-read my poem-draft out loud, tapping my foot to underscore certain rhythms. I often find myself tapping my foot while in the audience at poetry readings as well.

FWR: Whose work (they don’t necessarily have to be writers) are you invigorated by at the moment?

JH: Reading and writing are fairly simultaneous activities for me. Most of the time I spend “writing”, I’m actually reading from a stack of books on my desk. Sometimes my poems begin in dialogue with what I’m reading, or something I read may trigger a memory. Some poetry collections on my writing desk today include Refusing Heaven by Jack Gilbert, Judas Goat by Gabrielle Bates, Hard Damage by Aria Aber, Previously Owned by Nathan McClain, If Some God Shakes Your House by Jennifer Franklin, Might Kindred by Mónica Gomery and Mouth Sugar & Smoke by Eric Tran. The works of Elizabeth Bishop, Wislawa Szymborska, Lucille Clifton, Larry Levis and Terrance Hayes seem to be permanent fixtures in these stacks as well.

Musically, I’m all over the place. I also find that good stand-up comedy really keys in on important poetic aspects such as rhythm, specificity, word-choice and subverted expectations. What makes poems and jokes work are often one and the same.

FWR: I would love to hear more about how standup comedy influences or challenges how you approach your writing.

JH: To be clear, I’ve never tried standup, and am by no means an expert on the subject! I simply get inspired when I see it done well, much like reading a great book makes me want to write. You might’ve heard the phrase, “It’s funny because it’s true.” Both comedians and poets seek, as Dickinson put it, a kind of slanted truth—a fresh way of getting at shared experiences through the particulars and peculiarities that make life interesting.

FWR: On a related note, are there poets who use humor in their work whose work you enjoy?

JH: Yeah, Natalie Shapero writes some of the funniest – and sharpest, and most heartbreaking – poems around. Shapero has one poem from her latest collection, Popular Longing, that begins, “So sorry about the war—we just kind of/wanted to learn how to swear/in another language” and another poem with the lines, “Last week I read a novel about a man/so awful that when he died I wept/because it was fiction.” Much like a great comic, Shapero utilizes line-breaks and enjambment to dictate pace, build set-up, then deliver the punch-line. Carrie Fountain is another poet who writes these brilliant, humorous meditations on parenting, love, God, etc. They’re funny because they feel so accurate and lived in, and because humor isn’t so much the “goal” as it is a natural byproduct of writing about this strange, sad, wonderful world.

FWR: “Birthday” (which appeared in Four Way Review!) is such an incredible combination of restraint and impact. I am really curious about the editing process for this particular poem. Was the first draft pretty similar to the final version of the poem? Would you talk us through it a little bit?

JH: I appreciate that. Restraint is the right word here. A friend of mine, the excellent poet, Rosebud Ben-Oni, instructs her students to “be careful not to edit before you write.” Great advice, but that’s exactly what I wound up doing with this one, taking it line by line and slowly working my way down the page. So often, writing is an act of discovery, but with this particular poem – based on a conversation I’d just had with my daughter – I knew my target. It was just a question of hitting the mark and paring back language to make sure the poem didn’t spiral into sentimentality. By the time I’d reached the last line, the vast majority of my editing was done. My first version and final version of this poem are nearly identical.

FWR: Is there a poem in this collection that you were surprised to find yourself writing?

JH: Despite what I just said about “Birthday”, some of my favorite moments as a writer are when I surprise myself, or say something I didn’t know I knew. One poem from Let Our Bodies Change the Subject that took me completely by surprise was “Survival Mode.” That one is nearly a word-for-word transcription of one of the stranger conversations I’ve ever been a part of. I found myself more or less writing it in real time, in my head and on a napkin. Then I raced upstairs and typed it out. It was one of those rare occasions where a poem appeared before it even registered that I was writing one at all.

FWR: A poem I return to over and over is “The Other Side of Desire.” I could see an argument for placing a poem like this — one that establishes conflict and ambivalence — in the middle of a collection and I am fascinated by the fact that it comes so close to the end. Can you talk about that choice a little bit?

JH: That’s an interesting question. I guess I don’t think of “The Other Side of Desire” as a poem about ambivalence, but about commitment and love in the face of imperfection and the dailyness of existence. “The Other Side of Desire” directly follows “Spring Crush” and “Slow Dance” in my collection, both of which are poems about young, early and first loves. “Slow Dance” concludes: “Whatever I hold close begins then.” Of course, what sustains a strong relationship is more than just infatuation and attraction. It also takes work, mutual respect, and these constant, almost invisible decisions to be present in your life and the life of your partner. Placing this poem near the end of the collection, for me, was less about establishing conflict than owning up to the responsibility of our decisions, maybe especially our best decisions.

AN ENGINE FOR UNDERSTANDING: AN INTERVIEW WITH Willie Lin

Willie Lin’s debut poetry collection, Conversations Among Stones, will be published in November 2023 by BOA Editions. Simone Menard-Irvine interviewed Lin for Four Way Review.

FWR: I would like to start out by first asking about what it’s like to be publishing your first full collection of poetry? What was the process of writing and assembling like in comparison to the publication of your earlier chapbooks?

WL: My urge in assembling manuscripts is always to pare down. Because of this impulse, assembling my chapbooks felt like a much clearer and more straightforward process. For the manuscript that became Conversation Among Stones, I struggled with holding it in its entirety in my mind and had to be more deliberate in my approach. I understood how certain constellations of poems fit together but was a bit overwhelmed with shaping the manuscript as a whole. At one point, I actually made a spreadsheet of all the poems that I thought might belong in the book and notated and ordered them according to a few different axes to help me see how they might fit together.

FWR: Your title, “Conversation Among Stones” brings up questions of action between the inanimate. What inspired you to frame your collection under this title?

WL: That idea is definitely part of what I had hoped to evoke with the title—of speaking to the inanimate and what can’t or refuses to speak back, of language spanning, filling, straining, or distending across gaps, of failing to say or hear what matters. I think these intimations are a good way of entering the book, which I hope worries and enacts some of these concerns regarding the capacities and limitations of language.

FWR: My next question is in regards to the variations of length in the poems. In “Dear,” which is only two lines, you write “A knife pares to learn what is flesh. / What is flesh.” Both a statement and a question, you ask the reader to consider something so simple, yet laden with ideas regarding the body and violence. What was your process in developing these shorter pieces, and how do you see them functioning within the broader collection?

WL: Poems can beguile in so many ways, but I’ve always loved the compactness of a short poem. Part of it is how easy it is to carry them with you in their entirety and turn them over in your mind. Since I first came across Issa’s “This world of dew / is a world of dew. / And yet… and yet…” in a poetry class almost 20 years ago, I’ve been able to carry it with me. I’ve learned and forgotten countless things in poems and in life in the ensuing years, but have kept that poem almost unconsciously, without effort. Another aspect of short poems’ appeal to me is the paradoxical way time works in them. A short poem’s effect feels almost instantaneous because of its brevity but time also dilates across its lines. The duration seems somehow mismatched with the time it takes to run your eyes along the text. In Lucille Clifton’s “why some people be mad at me sometimes,” the body of the poem answers the charge of the title in five short lines:

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine

That last one-word, monosyllabic line, especially, seems to take forever to conclude. The compression of the poem—the words under pressure from the wide sweep of white space—exerts a redoubled, outward pressure and reverberates.

My poem “Dear” started as a longer poem (not longer by much, maybe 10 lines or so). At one point, as an experiment, I took out all the “I” statements in the poem and arrived at the version that exists now. Often, that’s how it works. I try different approaches and revise, sometimes rashly and foolishly, until something jostles loose. When I finally got to the two-line version of “Dear,” for me, the fragmentary nature of it fit with the precarity of its assertion and question. How the shorter poems appear on the page also matters in that I wanted the blank expanse that follows the poem to function as an extended breath. Because the book proceeds with no section breaks, it made sense to me to vary the lengths and movements of the poems to establish a kind of cadence, a push-and-pull.

FWR: In thinking about the themes that circulate throughout your work, a couple of specific ideas stand out as particularly potent. One is the issue of memory; the violence, complexities, and confusion of your past run their threads throughout the collection. In “The Vocation,” you write, “In the year I learned / to cease writing about history / in the present tense, / I was the silence of chalk dust, / of brothers.”

It seems like history, for the speaker, is something to be dealt with, instead of accepted unquestioningly. What does writing about the past, be it in present tense or not, do for you as an individual? Does confronting the past through writing work as a catharsis, a way to process, or does it instead serve as a conduit to expanding upon the ideas you wish to convey?

WL: I think memory—and the process of remembering—is an engine for understanding and, by extension, meaning. For experience to make sense, we have to remember. Knowing or thinking can’t really be separated from experience. It’s also true that memory, personal and communal, is restless and malleable. I have an image of the past as a landscape of sand dunes. The shapes drift. They slip, they resettle. How things feel in the moment can be one kind of understanding, how we remember them, how they shift, linger, rise, how they appear in the context of things that have happened since or what we do not yet know are other kinds.

In Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay,” when challenged on why she remembers “too much”—“Why hold onto all that?”—the speaker responds, “Where can I put it down?” I suppose poetry for me is one place to put it down. (Though I don’t think I could be accused of remembering too much in life. I have a terrible memory.) In writing a poem, I’m making a deliberate attempt toward an understanding, however provisional. Poems are good spaces for holding and turning, for thinking through and imagining, for venturing out—and that is the final, extravagant goal, to reach out and connect with someone else. In my poems, I want to make a path that leads inward to the center—and out.

FWR: In that same poem, you confront another central theme: men. When you mention men, they are typically described via their participation in fatherhood or brotherhood. You write, “the men/slammed the table when they laughed/at their circumstance, or drank/too much to learn what it meant/to have a brother, or were true to/no end, or tried to love their fathers/before they disappeared into/hagiography.”

Masculinity here seems to be defined as a relational identity, one that is constituted by lineage and socialization. I would love to hear you speak on your relationship with gender norms and roles, especially in your writing.

WL: This question is particularly fascinating because I can’t say I conceived of my poems working together in this way, even though of course you’re right to point to how often these types of familial terms come up. I suppose part of the answer has to be how the poems relate to my autobiography. In my family, my mother is the only woman in her generation. She has two brothers and my father has two brothers. I’m also the only woman in my generation. I have three cousins, all men. I’m an only child who grew up in China during the one-child policy, so all around me were lots of children just like me, who’ll never know what it means to have a sibling. I felt a bit of an outsider’s fascination with those types of relationships and inheritances, especially as I got older and became more aware of the other social forces at work that historically favored sons. I think poetry can function partly as personal interventions in cultural history and memory, holding the ambivalences, contradictions, and idiosyncrasies that live at those intersections.

FWR: We see many instances of place in relation to memory, but there are only a few instances in which those locations are given a specific name, such as in “Teleology” when you mention Nebraska. Can you walk us through your approach to location in your work and what places need an identifier, versus places that can exist more specifically within the speaker’s domain of recollection?

WL: I think generally the idea of dislocation is more important than the locations themselves in terms of how they function in the poems. Saying the name of a place evinces a kind of ownership of or intimacy with that place. For many of the poems, in not naming specific locations, I more so wanted to evoke a sense of rootlessness and for the intimacy to be with the speaker’s uneasiness within or distance from those places. “Nebraska” in “Teleology” is a departure from that model not only because it offers a specific name but also because I think in this instance Nebraska is not a real place but an imagined one—a kind of projection that stands in for other things (the poem says, “like Nebraska,” “many Nebraskas,” “Nebraska is a little funeral”—my apologies to the real Nebraska!).

FWR: In “Dream with Omen,” you end the piece with “I would like to rest now / with my head in a warm lap.” This is one of my favorite lines, because it both speaks to the sound and feel of this collection, and it interrogates the two balancing aspects of this collection: that of memory and the mind, and that of the physical present. The speaker in many of your pieces seems to be constantly grappling with the subconscious world, made alive by dreams. How do you view or negotiate the separation and/or melding of the subconscious and the “real” world? Does the mind and its preoccupation with the past stop the self from fully engaging in the present? Can the speaker rest in a warm lap and still accept the darkness of the subconscious?

WL: In putting together this book, I became conscious of how often I write about dreaming and/or sleeping. I felt sheepish both because we are told often (as writers and as people) that dreams are boring and because maybe these poems betray my personal tendency toward indolence.

It’s interesting to align the past with the subconscious and the present with the “real” as you do in the question. I do feel the tension between those things in writing even as I also feel that thoughts are real and fears are real, etc., just as senses—how we experience the physical world—are real. And it feels a little silly to say this but I have a kind of faith that our subconscious is working away trying to help us come to terms with what occupies us in the real, present world even as we sleep and dream. Everyone who writes has at times had that sense that what they are writing is received, as if they are tapping into some other world or force. Maybe that idea is analogous to what I mean.

Memories, dreams, the subconscious, however the particularities of the mind manifest, feel consequential in their bearing on lived experience—they are how the real world lives in us. There is no unmediated world. Or if there is, we don’t know it. We must encounter the world personally because we are people. All this is to say I’m still learning line-to-line, poem-to-poem how best to articulate that kind of interiority in a meaningful way, without leaving the reader adrift. Leaning on dreams can make a poem feel muted and entering memories can feel like putting on the heaviness of a wet wool sweater and those things do not always serve the poem. I hope for my poems’ sake that I get that balance right more often than not.

Willie Lin was interviewed for Four Way Review by Simone Menard-Irvine.

Simone Menard-Irvine is a poet from Brooklyn, New York currently pursuing and English degree at Smith College. Her work has been published in HOBART and Emulate magazine.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview

INTERVIEW WITH Ayesha Raees

Ayesha Raees’ fabulist and fable-like chapbook, Coining a Wishing Tower (Platypus Press Broken River Prize winner, 2020, selected by Kaveh Akbar), is composed of 56 prose-like blocks—give or a take a few half-fragments.

These prose-poems, which are whimsical, profound, vulnerable, and full of pathos, grief, and transformation, depict complex relationships between parents and child, religion and women, lovers and the beloved, wishers and wish-granters. There are three separate narrative strands, teleporting between Pakistan; New York City; Makkah; New London, Connecticut; as well as more abstract spaces, like a Desire Path, as well as Barzakh (which, the chapbook tells us, Google calls a “Christian Limbo”).

The first narrative involves House Mouse, who climbs and climbs until the “end of all possible height” and finds itself in a wishing tower which can grant all its wishes. House Mouse performs various rituals including the ritual of death—in which both House Mouse and the tower die. The second strand, taking place in a wooden house in New Connecticut, involves three characters: Godfish, a cat who is in love with Godfish, and the moon, who is also in love with Godfish. And finally, there is the more realist narrative strand, with a female speaker—a daughter and an immigrant—who seems to speak for Raees herself, and her own personal experiences with family, religion, migration and displacement.

She is interviewed here by Cleo Qian, previously published in Issue 25.

CQ: How did you come up with the characters of House Mouse, the tower, Godfish, the cat, and the moon?

AR: Each character in the book embodies, not always wholly or too literally, a person of importance from my life. The book itself was conceived the night that I found out my best friend, Q, was in an irreversible coma due to a (eventually successful) suicide attempt. The characters in the book are my own reckoning with the different facets of the deaths we face in our lives before our eventual, more literal, ends. But I did not want this book to be so linear or literal; I wanted it to tackle death in varying ways.

House Mouse represents every young immigrant. Immigrants must leave their “selves” or “homes” for a better future, which is the mirage of the “American dream”—which calls for outsiders to come in and fill the gaps of a decaying system. Asian immigrants also, in many ways, are pressed for success or “height” to obtain ‘value’ from a very young age.

As a poet, “House Mouse” is also a play on words. What happens to a common house mouse when it is without a house? What happens to a young immigrant when they leave their homes for the world’s seductions?

The wishing tower is a symbol of the Ka’abah but is also something of extreme physical height, an unreachable thing. “Coining” in the collection’s title reflects stoning—a visual gesture, with prayers or wishes. Godfish is a play on goldfish, but this character also represents another close friend of mine, A, who was another young immigrant who left home to America to pursue another life and was lost in a tragic way. And the cat and the moon are, at the end of the day, spectators, both holding power but choosing to practice it in different ways; they are two faces of a white savior complex and American passivity.

I don’t believe I would have been able to say all I wanted to say without the aid of characters in this book.

CQ: Let’s talk a little bit about the settings mentioned throughout the book. What is the significance of the setting New London, Connecticut? Early in the book, you write, “I have never been to New London, Connecticut.” In the narrative of the Godfish, cat, and moon, New London is both real and unreal, and the wooden house they live in is centric to “unnatural happenings” and set apart from the “real life giant black road.” And what about the sites of pilgrimage throughout the book? Is America also a site to make a pilgrimage to, or is it a place to escape to?

AR: I have a love for places and the social cultures they inevitably hold. I am someone who has been in constant movement her whole life, and I believe places to be their own characters, to have their spirits. Therefore, the different locations in the book are all real, even the unreal ones. They are their own breathing, living organisms.

And that’s how New London, in Connecticut, feels to me. I have never been. In the book, it is a place of “unnatural happenings” as, just as written in the book, it is a place where Godfish died.

The character who is embodied in Godfish was my high school best friend, A. He went to Connecticut College (in New London, Connecticut) and was hit by a drunk driver while he was crossing the road at night to go to his dorm. The drunk driver, instead of calling for help, pulled A’s body aside and drove away. Leaving him. Right there. To spend a cold December night outside. He was found the next day. His date of death is merely an estimation.

I was myself a sophomore at Bennington College when I received the news. This was December 2015. I was devastated. Over the years of grieving, New London, Connecticut became a significant image for me. The side of the road A was on was very real. I don’t know what it looks like in real life. But in my head, there is a whole image. I live with the happenings of that night every time I am grieving. How can I have such vivid imagery exist when I was not even physically present? That’s the power words have over me.

The moon that captures and cannot fully lift Godfish embodies “moonshine,” intoxication, which failed both Godfish (and A). In the end, my friend was a gold marking on the road. And I believe when I started to write about Q [my friend who passed away after being in a coma], A came forward into the poetry as well. They both took me on the journey of characters and settings, and the book’s narrative reckons with all our losses and its impact.

Is that a sort of pilgrimage? I believe so.

CQ: The book opens with House Mouse climbing and climbing until it gets to the wishing tower. Godfish wishes to be able to swim to the sun, its beloved. The moon wishes to draw Godfish to itself. In Islam, Jannat-ul-Firdous, we learn, is a “place in heaven that is of the highest level, reserved for the most pious, the most special, the most loved.” Do you think the striving for height is a universal human desire? How do height and religion intertwine?

AR: Who are we but an accumulation of our wantings? Humans have inane, uncontrollable, desires that make us get out of the ordinary and strive for something that can give us, even for a single moment, a rich breath of fresh extraordinary. To be human is to be full of wanting, to exist in that kind of inevitable strive. And that kind of striving will always achieve some kind of height.

But my goal through the book, and of course for my own reckoning as a young ambitious Asian immigrant in the American landscape, was to ask what those systems of value ask of us. These “heights” we climb to that are a measure of our worth, giving our human life a value. In order to have value, we keep climbing. But until when?

I was thrown into this disarray because Q and I were ambitious young Asian women from so-called “third world countries” and quite alike in our dispositions. We wanted to be accomplished. To have value as individuals and not be reduced to our Asian womanhoods. But that striving killed us. I watched her fall. And I found myself falling. Like most Asians, we were sold to ideas of hard work leading to value, such as our grades, the length of our CVs, the honors and fellowships and residencies and awards. We were accomplished. But we did not have enough value to win the system that was built against us.

So what did we strive for?

As I was grieving, religion became my literature and God my mentor. I grew up with Islam but as with most religious countries, religion seeped in as a way of life rather than a radicality. Islam is a part of my cultural identity. It is part of my language. Islam is a constant reminder of how to live a life that prepares us for death. And even though I am (and was!) so young, to be handed so many deaths of so many loved ones left me in disarray. I was alone in the American landscape without much support or, as we all have experienced our capitalist systems, empathy. When I finally turned again towards Islam, I was looking for some sense that the West, and Western literature, could not afford me.

I will always say that I am not a religious person. After all, religion is a tool to control the masses. I don’t want Coining A Wishing Tower to be a religious book. I am, however, deeply spiritual. I do have faith in the unknown. I do believe in a God. Maybe when I am brave enough to proclaim it externally, I can even say my God. I have belief in the many rituals that help us decipher the literals of our lives towards a healthy figurative. A true kind of poem. It is inevitable for me to not see God with poetry.

CQ: Many of the prose poems—and the arcs of the House Mouse, the tower, the Godfish, cat, and moon—are written in a parable-like tone. Some of them also verge on fairy tales. You have such wonderful lines and imagination when, for example, House Mouse is cooking in the tower:

“House Mouse cooked fish for the first meal, corn for the

second meal, and melted cheese for the third meal. The

tower is one room full of great imaginings working towards

not staying imagined…”

Or when the moon tries to bring Godfish to itself:

“With every mustered strength, the moon lifts the water, rounds

Godfish into a dripping ball and pulls it through the opened

window only to bring it to a float and a hover in the storming

snow of New London, Connecticut….”

What was the influence of parable and fairy tale in your writing of these poems? Do you consider these narratives allegories?

AR: I celebrate poetry because a good functioning poem has great intentionality. If you spend enough time even with a single line, you can see how the poet has chosen to lay the words next to each other the way they are. Nothing is random. And everything adds to something else.

I do a lot of work with symbolism and imagery, often lent from my own life. I am always in awe at the contrast and the magic I see in front of me. For example, I am currently in Paris, sitting in a gorgeous reading room at Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Public Library of France) answering these questions, where I find myself watching a parade of silent children running through the rows of hunched working adults. They are not laughing. Or making any kind of noise. They are just running through the gorgeous rows of tables. What a contrast! What image and magic! And hardly anyone is looking up! Doesn’t that feel like a fairy tale? Or an allegory? Children running through a grand beautiful reading room of a world-famous library full of frowning adults?

I do the same in the verses you have pointed out. When I put [these contrasts] of the imagined and unimagined together, I surprise myself.

CW: Do you believe in epiphany? How does epiphany play a role in these poems?

AR: I believe in wonder, which can be quite like epiphany, but is not always the same. Epiphany feels like a lightbulb moment of occasional discovery, but wonder feels like a series of discoveries that were always present but are now fully being seen.

In this way, the form of the book holds a kind of wonder. It is an epic told in fragments. Even though I wrote it linearly and the editorial process did not include rearrangements but just clarifications, I saw how one narrative thread began to breathe while still supporting the other threads.

When I read the book out loud in readings, I flip through the book at random and read pieces from it. I am faced with more wonder in this as well.

CQ: Google is also frequently cited throughout the poems. Often, Google’s word is taken as factual and fills in missing gaps in the speaker’s knowledge—e.g. Google speaks on the status of New London, Connecticut, as a small city; on how many lives cats have; on what Islamic Barzakh is. Why did you invoke Google and what is the role of human technology in understanding these characters and poems?

AR: Isn’t Google some form of god now? We rely on it for all our small and big questions and immediately believe what it tells us. “Google says…” instead of “God says.” I find in both these common phrases a kind of significant mimicry.

In a past that’s not too far off (I am thinking of my parents’ lives), information was not accessible at all. My parents were probably faced with so much unknown but still had to strive forward with whatever understanding and skills they did have. They couldn’t just Google how to exactly use a new microwave they bought or how to apply for a visa to travel. In these observations, Google has become such a huge part of our contemporary lives that without it, we wouldn’t often know what to do. And with it, we often are also told how to live a life and exactly what to do.

Maybe I wanted to have Google in the book because so much of our consolations and salvation hinges on asking. In the past, we sat in prayer and asked. And now we get on our phones, maybe our hands poised ritually the same, and ask. We get answered in both ways. We believe. And sometimes, we don’t.

CQ: Another theme that pops up in the latter half of the book is forgetting. Of the Islamic heaven, you write, “Any kind of remembrance of our past lives, any regret, every love, it will all be flushed.” You, the speaker, ask if you will be forgotten on the day of judgment, and the mother says, “It’s inevitable…you will forget me too.” When the cat finds Godfish, dead, you write, “Would death tear them apart to a degree of absolute forget?” These lines really tugged at my heart. The fear of forgetting my loved ones after death is terrifying . How are these poems a response to the question of whether death is the ultimate forgetting?

AR: What we don’t remember also brings us relief. That’s the concept most Muslims have about death and afterlife. If I don’t remember the extent of love I feel for my mother, I would not feel the extent of her loss. I would be relieved of grief and the pain of it.

This is scary. But also, to some degree, comforting. There is consolation in thinking we won’t always be yearning for the ones we lose.

I have tried to tackle the question of love and endings through the poems in small and big ways. The last prose block of House Mouse “returning” holds that life and death can exist in mimicry. But what bridges each ending with another beginning is change and transformation.

CQ: There are a series of transformations: Godfish into a fish, the wishing tower into a pile of rubble. Are these “failed” transformations? Are they an inevitable part of the cycle of life?

AR: I don’t believe in “failed” transformations, and I think maybe that was what I was trying to truly say throughout this epic. Even though Godfish loses its God-ness, its existence still transformed the moon and the cat. The wishing tower is no longer able to grant wishes, and then it loses its life. But it transforms into something else, even if that is rubble which will erode away.

These losses are, in some ways, an indication of life’s inevitable end, yes, but [writing this book] also gave me the gift [of knowing] that there will always be some kind of other journey. Any end we think of is a ripple effect towards something else, beyond comprehension.

These fragmented thoughts are captured in the fragmented poems. We can see the “afterlives” of House Mouse, the Godfish and the tower. [I wanted to show how] there is never any true failure in our conventional ideas of failing. Things that “fall” fall to somewhere else.

CQ: Do you consider these poems of loss?

AR: Absolutely. But not only. These poems are full of grief. But also consolation. Also philosophical nurturings. They are an encouragement to move away from our unconventional thinking of the most universal experience of loss itself.

CQ: At the end of the book, House Mouse is somehow resurrected. I loved this ending, which felt joyous, miraculous, and yet also sad and full of grief because there is no one around to meet House Mouse. What are we to make of House Mouse’s return to life? What is House Mouse returning to?

AR: House Mouse holds huge parts of me as well as huge parts of the speaker, which, of course as poets say lingo, is both me and not me. The speaker leaves home, Pakistan, and goes to America, fulfilling her teenage dream to leave, but the speaker also returns. And with every return, there is change. Decay. Death. Loss. Transformations.

And each immigrant really asks these questions if they return [to where they have left]: “What am I returning to?” “What makes life life here and how much of it I have left?” “Who waits for me and who could not?”

“What has died and what still lives?”

Returning is hard. It is full of lamenting and an inconsolable feeling. We have to reckon with the relativity of time, the loss of romance, and changes that override our initial memories. House Mouse finally returns to the home which it left in the first prose block of the book. But so much has changed. What is home now?

I think there is consolation and love in the fact that we have our return. Even if our parents die. Even if our houses change. Even if the furniture gets full of dust. Just because there is this kind of loss, does not mean we do not feel all the presence of what home is there. Maybe, in life, forgetting can relieve us of pain, but remembrance reminds us of the original love we were given, however much it has been transformed.

CQ: You published Coining a Wishing Tower during the lockdown. Where were you, location-wise, when you heard that your book was accepted for publication? How did COVID-19 affect your experience writing and publishing this chapbook?

AR: This is actually a funny story. The day I got the email that I won the Broken River Prize from Platypus for the book was also the day Biden won (or, well, Trump lost) the elections—November 7 2020. We were all under strict Covid lockdown, but because of the election results, the streets of Brooklyn were flooded with cheers and shouts and music. We all ran through the streets. In that way, I felt I was also celebrating my own little win of accomplishing a dream (the wish I had coined a long time ago). The book was mostly written in 2019 around the loss of Q. But this book definitely was a huge victim of the pandemic aftermath. What with delays in publishing and then my press’s bankruptcy, my book only had a life in this world for one year. But I believe in its return. The life after its life.

CQ: What’s next for you?

AR: Even though I often fail to keep it as simple as the words I am about to say, all I truly desire is to keep writing. I am deeply in love with poetry. And I don’t think this affair will end at all. I am hoping to keep at it and, in small and big ways, keep being read.

To more poems! To more books!

Ayesha Raees عائشہ رئیس identifies herself as a hybrid creating hybrid poetry through hybrid forms. Her work strongly revolves around issues of race and identity, G/god and displacement, and mental illness while possessing a strong agency for accessibility, community, and change. Raees currently serves as an Assistant Poetry Editor at AAWW’s The Margins and has received fellowships from Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Brooklyn Poets, and Kundiman. Her debut chapbook “Coining A Wishing Tower” won the Broken River Prize, judged by Kaveh Akbar, and is published by Platypus Press. From Lahore, Pakistan, she currently shifts around Lahore, New York City, and Miami.

INTERVIEW WITH Sarah Audsley