OCTOBER INTERVIEW with EDWARD SALEM

Edward Salem is a poet who hasn’t lost his sense of humor. “Palestinians,” he shares in our interview, “are insanely funny.” It’s this sense of humor that jumps off the page of Salem’s debut poetry collection, Monk Fruit, surprising readers, even as he’s tackling topics like the occupation of Palestine, American imperialism, torture, and genocide. Salem will take you to Gaza—but you’re going to stop by the tchotchke bin at Burlington Coat Factory on the way. Described by its publisher, Nightboat Books, as “like Rumi on acid,” Monk Fruit speaks to the immediacy of our current moment while also taking a 250,000-year lens to humanity, inviting readers to interrogate their place in it all—even, perhaps, without losing optimism entirely.

Edward Salem is interviewed by E Ce Miller.

FWR: Monk fruit doesn’t actually appear in any of the poems in Monk Fruit. For those not familiar, monk fruits are these trellised, blossoming squash, native to East Asia, named for having been grown in monastery gardens for thousands of years; now they are more widely known as a trendy weight loss hack/artificial sweetener substitute. Am I reaching too hard for a metaphor here? What were you hoping to evoke with the title of the collection?

ES: Thank you for bringing in this context. There’s definitely something to that, the play of high and low, like Buddha on a coaster. And I like how playful it sounds, “monk fruit,” and how slippery the associations can become when you read the book through the lens of the title—I think it manages to hold a lot of different motifs together: children, spirituality, sexuality, corporeality. Poems as fruit of the psyche. It can also serve as a metareflection on myself as a poet dabbling in eastern philosophy, but in this way that is kind of impish or outré.

FWR: There are so many flying insects in this collection. Some are trapped, before facing violent, untimely ends: crushed, clapped to death. Bees are military drones, hornets are “cancer picked from [a] mother’s lungs.” A few seem to offer a touch of whimsy, like the flea who is stunned by a fluffy sweater. What’s up with all the flying insects?

ES: I just saw the new Superman movie, and there’s a scene where Superman flies to save a squirrel from a falling building, acknowledging the sanctity of its life. It’s fun to imagine how busy Superman would be if his mandate included insects.

FWR: The poem “Buddha’s Bad Meal”, which describes a bee trapped in a juice glass, reminded me of this Buddhist koan about a dragonfly caught in a spider’s web, which essentially asks whether an observer should intervene and free the dragonfly. The most earnest students, I think, incline toward freeing the dragonfly. But what of the spider’s hunger?

The narrator in your poem says, “It wouldn’t matter if I rescued the bee or let it drown.” There’s this question many of the poems in Monk Fruit seem to be asking: Does it really matter what we do to each other, and if it does matter, on what scale? Can you speak to this?

ES: I love this question, thank you. And thanks for sharing the koan. It reminds me of an inspiration for the poem, a scene from Luis Buñuel’s film Viridiana. A man sees an exhausted dog tied to a moving cart, being dragged along the road. Out of compassion, he buys the dog from the cart driver to save it from this cruel treatment. But immediately after this act of mercy, another cart passes by, dragging another dog behind it.

Years ago, when I was living in Beirut, before I had really contended with Buddhism and Vedanta, a friend suggested detachment as the only adequate response to the cruelty of the occupation of Palestine. He was speaking to this notion that engaging, in and of itself, perpetuates injustice. That only through stillness and detachment can one move anything. I can’t tell you how appalled I was by his stance, as if we should lie down while our people are tortured and killed. But, as it goes with certain Eastern spiritual traditions, it’s only through direct experience that you start to understand a perspective that first seemed so cold. I think now that my friend was trying to say—how did Ram Dass put it? Police create hippies and hippies create police.

Back to the question of scale, I remember in the early days of starting City of Asylum/Detroit, we were meeting with a possible investor and he was like, so how many exiled writers will you bring over every year? He was expecting the answer to be like 100 or at least 10. When we explained how complicated the visa process alone would be, and that our mission was to provide deep, multi-year support to one fellow at a time, he was deflated. And I get it. At this moment, we’re supporting two Palestinians from Gaza through our new fellowship in exile (largely buoyed by the boundless optimism and energy of my cofounder, Laura Kraftowitz).

At the same time, compared to the number of Palestinians experiencing genocide, helping two people feels like a drop in the bucket. I live in the contradiction that exists between my philosophical pessimism, exemplified by the drowning bee or the abused dog, and the life-affirming hope inherent to providing these fellowships.

FWR: “Give What You Can” is a poem I read over and over—the way it is written invites readers into this sort of breathless repetition. It made me self-aware of how I relate to the media I consume. The poem mimics scrolling through social media, putting language to the image-heavy sensory excess most of us have grown accustomed to. I wonder about the effects of, for example, viewing footage of ICE raids in the same 1:1 framed feed as a best friend’s new baby photos, of considering an image of an infant starving in Gaza immediately before a celebrity’s ad for green laundry detergent—it’s all sort of occupying the same brain space, all landing in the same frequency in the sympathetic nervous system…

A few poems later, we get “The Palestinian Chair”, with the line “…you realize that / You were there. / For all of it. / It was all you.” These two poems struck me as a sort of call and response. Technology facilitates a sense of “being there” for everything while also fostering a kind of dissociation from all of it. Do you have thoughts on this?

ES: I recently watched a clip—on social media, of course—where Arundhati Roy talked about how unnatural it is for us to take in all of this information. How we can’t hold it and shouldn’t expose ourselves to it all, how she thinks it’s making us spiritually sick. And I agree with that. But in a time of live-streamed genocide, you have to reconcile that with the moral failure of not looking, or rather, looking away from the images that Palestinians in Gaza are asking us to witness. This poem sort of documents the dizzying experience of watching a nightmare unfold, and also watching the direct action and creativity harnessed to resist it.

I almost hate to say it, but I think a collection of poetry is often sequenced to give the reader a parallel sort of whiplash. You don’t want a stretch of poems to blur into one another, so you keep the reader on their toes through juxtaposition, tone shifts, etc., in a way that somewhat resembles the deliberate scramble of the algorithm. But the key differential is that poetry sensitizes where the algo desensitizes. Poetry is kind of the anti-social media.

FWR: For all the intensity in this collection, there are lines and images that I also found funny, if wry. The poem “Tchotchke” features a chrome Ganesh bought from the clearance bin at Burlington Coat Factory. “Fasting for Gaza” includes the line “Jenny Craig should advertise with Al Jazeera.” What do you think irony has to say to reverence, levity to gravity? Will we be telling jokes at the end of the world?

ES: The book is dedicated to my late father, to whom I owe my fucked up sense of humor. He was deeply disgruntled, disdainful of what Zionism and American imperialism were doing to his country and its neighbors, and at the same time, he was hilarious. After dinner, he’d stand up and announce to the family that he was going to the bathroom “to pray,” and when he emerged, he’d stand in front of us and make the sign of the cross, pronouncing Latin-sounding gibberish, “dominos patros bibiscos,” cracking himself up every time.

Palestinians are insanely funny. It’s something that gets lost when we’re fighting for survival in a genocide, but gallows humor is intrinsic to our culture. Yasmin Zaher is hilarious, Adnan Barq is hilarious, Mohammed El-Kurd is hilarious, Randa Jarrar is hilarious. My sisters are hilarious. We’re a funny fucking people, but there’s a pressure on us to be earnest victims, to one-dimensionalize ourselves. I’m just trying to be myself—and I’m my father’s son—by making room in this book for the full expression of that.

FWR: In “L’Origine du Monde”, you write, “Surprise myself every time I begin / a new poem without Palestine, // though nothing is my other obsession,”. The omission of “I” before “surprise” made me wonder if these lines were a command or (and?) an expression of surprise on the narrator’s part.

When did you begin writing Monk Fruit? Could you discuss the process of writing this collection? How do you experience writing poetry, which is perhaps the antithesis of the “hot take” in the face of… [gestures at the world].

ES: I love this question, and your interpretation of the omission of “I” as a command. Can I say yes? I think the truth is more that I have a habit of starting poems with “I,” and on a purely intuitive level it felt right to lop it off. In writing Monk Fruit, I trusted my intuition, even and maybe especially when something felt like it might be wrong or risky or too demented in some way. I wrote it concurrently with a second book, Intifadas, out this spring, which is more grounded. I mean, it’s still demented, but with Monk Fruit, I really followed that energy to work out my obsessions and excavate the weird, profane images living in me, without holding the reins too tightly on how they show up on the page.

FWR: Does your work with City of Asylum/Detroit inform your poetry, and vice versa?

ES: Naji al-Ali, the Palestinian political cartoonist who created Handala and who was assassinated because of his art, was one of my first and primary artistic heroes, especially in my formative years as an artist. Geoffrey Rush’s portrayal of the Marquis de Sade’s imprisonment in the film Quills also left a deep impression on me. His anguish, his defiance, how he fell apart, and how he smuggled his manuscript out—not unlike the Palestinian prisoner Wisam Rafeedie’s The Trinity of Fundamentals.

In another life, I was an artist. When I lived for a while in Ramallah, my family was always worried because I was making provocative performance art in public spaces. Of course, in Ramallah, the Palestinian Authority was the one to worry about, since they were the enforcers of Israel’s efforts to quell dissent. They arrested me once. Even for innocuous gestures, like a performance where I threw pillows over the Apartheid Wall, I had to have lookouts watching my back. But now I live in the US, and there is, at least for now, still a level of safety.

A friend from Mexico recently described living in the US as hiding behind a bully for protection. And my work at City of Asylum reminds me not to take that position lightly.

FWR: I want to end by asking if you have an answer to the question “Barbecue” posed:

“250,000 years after / the discovery of fire, / we still ate raw meat. / But good things come

to those who wait. // It took us a quarter / of a million years / to arrive at barbecue, / so give God a little / more time.”

Those of us who don’t have a quarter of a million years, which is to say all of us, how might we better fill our waiting? Or, perhaps, that is the wrong question—maybe it is in the constant, desperate filling that we are getting ourselves and each other in trouble? What do you think?

ES: At the risk of sounding like an optimist, I’m not sure we’ll have to wait that long. Demis Hassabis, the child prodigy who now runs DeepMind and who has spent his life researching artificial intelligence, puts our chances of creating AGI [Artificial General Intelligence] by 2030 at 50%. Other researchers and thinkers I’ve long followed in this space are similarly optimistic. Hassabis won a Nobel prize for his work using AI to fold proteins, which will likely be involved if we’re ever able to cure cancer. I wonder about a super-intelligent entity that could eradicate social illnesses like Zionism and capitalism while heralding in universal abundance. I do worry that the technology is coming faster than we can prepare for it, but I’m also trying to hold a bit of hope for the vast good it could do.

I really hate to say it, but no form of resistance so far—neither violent, nonviolent, nor symbolic, certainly not poetry or speaking out on social media—none of it has stopped the ever-escalating genocide in Gaza. I’m not saying we should stop resisting, just the opposite. But I do wonder, and I’m the first to admit this does sound fantastical and maybe a little escapist, but if we merged with AI, could there be a paradigm shift toward empathy and compassion? I know it’s de rigueur to believe the opposite, that the techno-feudalists are tightening their grip as we move deeper into fascism. But nothing else is working the way we need it to. Despite our best efforts, we’re still failing the people in Gaza, Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan, Haiti, to say nothing of the eighty billion land animals we murder annually for food. Whatever the case, it seems likely that humans will evolve by merging with AI and technology. Monk Fruit deals a lot with the Big Bang, the origin of the universe and the nature of reality. I love thinking of the distant past, and the far future.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview, Poetry

SEPTEMBER INTERVIEW with LIZA HUDOCK

Addiction, death, and loss are everywhere in Liza Hudock’s debut collection, Reveille (released by Flood Editions in August), but they are not its actual subject. Instead, the poems wrestle—as near as it can be stated—with the world the speaker inhabits. Whether she turns her attention to a moth, the comparison between a pumpkin and a sonnet, Renaissance art, or a spoon, Hudock’s syntax and images are as surprising as they are breathtaking in their clarity and freshness as she explores, among other things, what it means to give care to people and places that may not be able to be healed.

FWR: I wonder if you could start by talking about the title of your book, which is the title of one of the later poems in the collection—how did you choose the title, or how did it choose itself?

LH: On military bases (and at summer camps, if the movies are true) reveille is the bugle call played at 7 am, usually as a recording over a PA system (it comes from the French command réveillez-vous; wake up). I either heard or pressed play on “reveille” almost every day that I was in the Coast Guard, and that experience did bring the word to my vocabulary, but it isn’t why I chose the title. My youngest sister used to throw water at the sparrows who lived in the bushes near our house when their chatter annoyed her. They hadn’t bothered me before, but I noticed them a lot more after she died. One morning, I picked up the copper pot she used to use for water throwing and I just brandished it in the birds’ direction, and they fell silent.

A few months later, I heard a concerto for choir by Georgy Sviridov called “Pushkin’s Garland”. One of the movements is called “Reveille.” The lyrics for this movement are taken from a Pushkin poem called “The Dawn is Struck.” I liked the figure of dawn as shorthand for the bell that is struck at dawn. I imagined the way a beam of light strikes a brass bell and the way that brightness has the sudden intensity of a bugle blast. So, this “Reveille” felt connected to the silence that rung out from my copper pot that day. That’s how I titled the poem. And then, it was just clear that it should be the title of the book.

Reveille does a lot of lamentation for my mother and sister, but I hope it feels full of possibility, like a new day—and by possibility, I don’t necessarily mean optimism; you can wake up full of fear, but certainty that the day must be different from the one before can be enough.

FWR: Let’s talk about influence. You mention Whitman, Stevens, Dante and Genesis in the book. Who would you say are your most important literary and/or artistic influences?

LH: Christine Kitano gave a lecture on poetic lineage while we were working on our MFAs—I’m sure you remember it, and I recommend it to everyone. That lecture is the foundation of my understanding of poetic influence and the reason I was able to find a voice for these poems. Basically, it’s okay that the pantheon of poets living in my heart is not upheld by any single school or tradition. I am the connective tissue. Part of my struggle starting out was that I felt like I was writing from nowhere and I needed to locate my voice somewhere in order to begin. My poetic lineage, which I didn’t realize I had built through years of reading until Christine talked about the fact that it was a thing, gave me the origin point I was missing. And, also, the lineage changes with me: Zbigniew Herbert, Wanda Coleman, Marianne Moore, Francis Bacon… I lived with them during those years. Before that, I read everything Pevear and Volokhonsky have translated from Russian. Lately, it’s been Dionne Brand and Fanny Howe. I’ve been reading The Faerie Queene almost every day… I don’t know why.

FWR: I’d also like to discuss visual influences and elements in your work. There are two ekphrastic poems in the collection: “After Mantegna’s Lamentation of Christ” and the gorgeous “After the Gold Leaves from Pelinna,” as well as a few other poems that describe or look at religious icons; your visual imagery is precise and stunning throughout the collection. (In the “Mantegna” poem, for instance, I love seeing the “whorled lake/ like a marble slab” and “the pads of [Christ’s] washed feet,/ torn skin like a gull’s/ wings in flight.”) Indeed, one of the hallmarks of this collection is your command of simile, image, and extended metaphor. I’m quite shy of similes in my own work because it’s so easy to write a hamfisted simile, and so hard to write one that really surprises and changes one’s way of seeing. But you jump right in, and after looking at them over and over again, I think they work because they are, when taken all together, intelligible, surprising, and mysterious—even when you work with an extended metaphor you’ll finish with a turn to something that resonates and opens up meaning without fixing it and snapping the poem and its meanings shut.

I think here, for instance, of “My Dead Folks Know They’re Dead.” In the wake of her losses, the speaker acknowledges a freedom that “Like a tulip/ […] comes fastened/ to the buried fist that feeds it, or the leaf/ that nourishes the fist.” At the end of the poem the speaker turns to her own “Mind// worming away at things, certain only/ of the first thing I said. The way/ I know the hard bulb by its tulip.” I’m still mulling all of the possibilities in these comparisons!

I want to ask, “how the heck do you do it?” but I suspect the answer is that it’s just how your brain works! So instead I’ll ask, is this a conscious process? Does it grow out of your precise observations of the natural and human worlds, or do you begin with the idea or state that you’re comparing to the vehicle you write about?

LH: My process grew from reading Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s poem, “Closing Time; Iskandariya.” It was the most perfect example of description I had read to that point and therefore one of the best poems I had ever read. I decided that if I could just look at whatever was in front of me and describe it, the words that came would be enough for a poem.

I wondered if the urgency of Reveille was a little unhealthy, by the way. It would have been appropriate for me to take a break from writing and then come back to the book about the year my mom and sister died with a measure of artistic distance. But you know Nietzsche’s famous sentence: “And if you look long enough into the abyss, the abyss will look into you,” right? I recently discovered the sentence that precedes it: “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster.” That’s exactly what was happening to me. I was bitter, treating life like a joke. Something compelled me to work on my descriptions every day, and that practice preserved whatever cooling coal of tenderness I had left for the future. So, the intention to describe was conscious. Figuration is the natural result of the effort to describe. I have an aversion to all that “like” too, but I did it anyway. Fortunately, my process has changed. Figuration is still there, but more vaporous.

FWR: I’m curious about how you think about craft, in part because we attended the same MFA program and studied with some of the same poets (though our aesthetics and approach are quite disparate—which is one of the reasons why I always love to talk about poetry with you!). What formal and structural elements do you particularly pay attention to in your poems, and is form something that you think about early in the composition process or that you arrive at when the poem starts to find its way?

LH: I don’t know about you, but I absolutely needed to learn craft. Getting an education didn’t ruin anything for me, if that’s what you mean. The wildness and the mysteries are still here. I think of structure in terms of syntax, and I do cast and recast a poem in different syntaxes until it feels right. Form, as in the shape of the poem on the page, is usually the last thing figured out. I will begin with such a clear vision of a prose block, and then it turns out the poem was destined to be long and skinny, for example. I handwrite until the words of a poem are pretty much settled and then send it through all kinds of forms once it’s on a screen. This can take years, but it seems a matter of dignity to find the shape a poem is waiting for.

FWR: Could you walk me through your process in a particular poem where the form went through this kind of evolution?

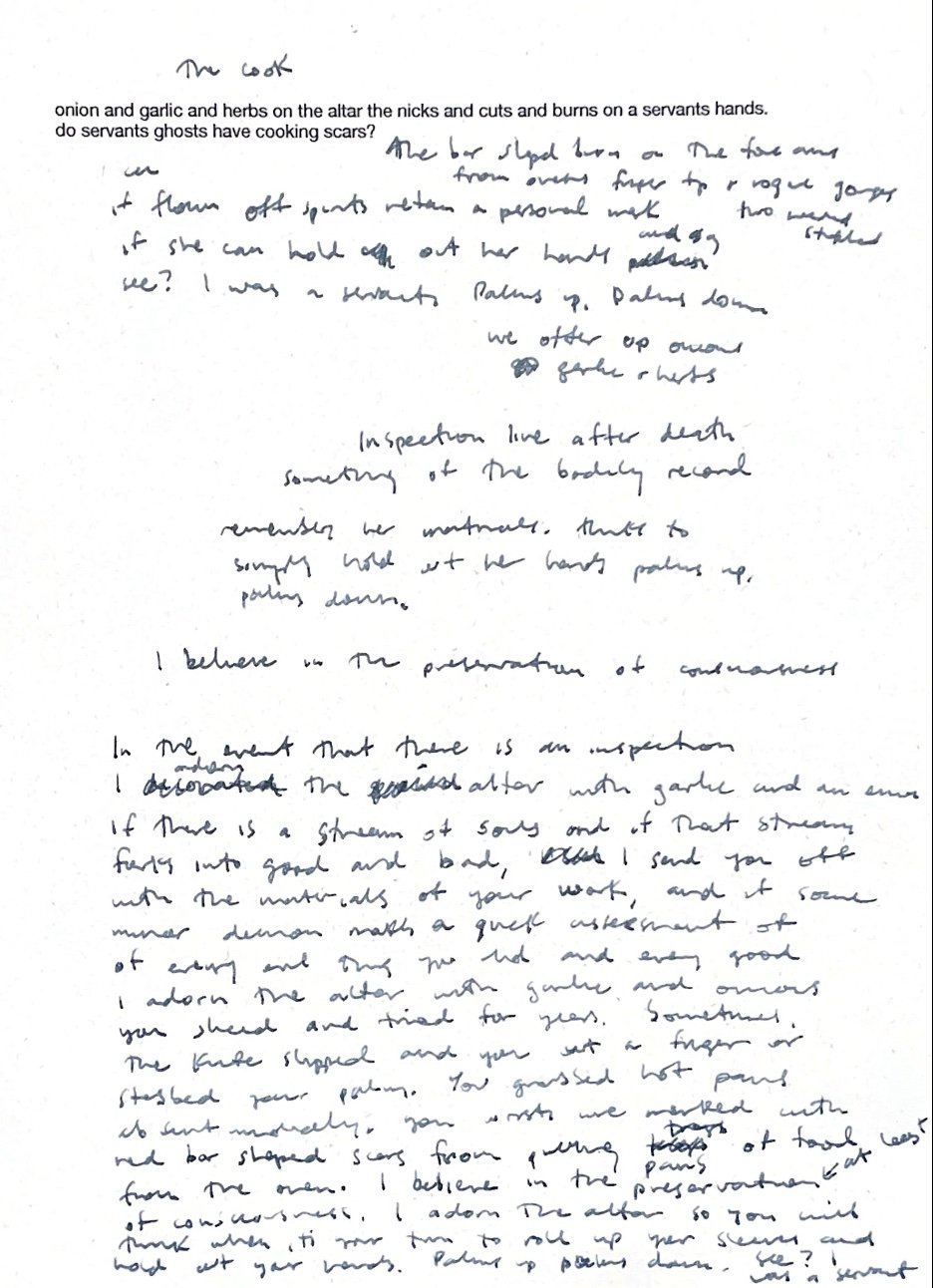

LH: Yes: for example, the first draft of “Funeral for a Cook” existed for a few months as just this short note. I printed it out on its own sheet of paper feeling that it might become a poem. A few more notes, and suddenly I was cramming the words in as a prose block to make it fit on one page. Once I re-typed the poem, I didn’t save the many formal variations it went through, but I can describe a couple. This poem is a loving gesture with a volta towards the end, so I tried typing it as a sonnet, but that wasn’t right. My favorite sonnets appear to discover themselves as they unfold; they feel surprised by their own turns. “Funeral for a Cook” seems to know its ending from the first word. The poem just wants the reader to trust it enough to follow.

Next, I noticed a couple strings of iambs that worked well as short lines, so I tried to type the whole poem in 3- to 4-beat lines and favored end rhyme where I could. In this form, most of the short lines cut against the syntax too much. I didn’t need the added tension between line break and syntax in a poem whose proposition was already so tenuous. It turned out to be a very willful, line-driven poem. The lines work like rungs on a ladder, allowing the speaker to advance her desperate imperative with a strange sure-footedness. Generally, if a line isn’t end-stopped with a period, it breaks at the end of a clause or otherwise natural breathing place. So, once I let each line defend itself as well as possible and allowed stanzas to group thoughts in a way that only strengthened the poem’s rhetoric, I landed on the shape that now feels inevitable.

FUNERAL FOR A COOK

In the event you come up for inspection,

I lay the altar with garlic and an onion.

If there is a stream of souls that forks into good and bad,

I send you to it with the materials of your work.

In case some minor demon makes a quick assessment

of all your evil deeds against the good,

I lay the altar with the garlic and onions you sliced and fried.

Sometimes the knife slipped.

You cut your fingers and stabbed your palms.

You grabbed hot pans daydreaming,

your wrists were lined with red scars

from the oven’s opening.

I want to believe in the preservation of consciousness.

I lay the altar so you might think,

if you are ever to be judged, to roll up your sleeves.

Hold your hands out and I promise never to tell you

what to do again.

Hold your hands out. Palms up, palms down:

see? I was a servant.

FWR: I’m fascinated by all of this, especially the way you noticed what wasn’t working about each form even as you recognized the impulse that drove that version. And, for the record, going back to your previous answer: yes—I absolutely did need to learn craft too! I had read and written a lot before the program, but I kind of rebuilt my understanding of poetry, both as a reader and a writer, from the ground up. Which brings me to where you are now: what is your writing routine like; what does your writing (and/or revision) process look like for you, and has it changed since completing this book?

LH: I don’t have a routine as far as time of day or length of time. I do tend to work in batches. I’ll have several poems laying out like wet canvases and sometimes I spend hours with them, sometimes I just make a change to one on my way to something else. The process of writing Reveille doesn’t seem repeatable. It took place in stages. At first, my sister and I were sleeping every other day, tending to our mom constantly. We did her hospice at home. I wrote down an image if I could and just promised myself to get back to it. Our youngest sister died eight months after our mother. So, Reveille dwelt amongst cortisol and insomnia and grief. I sensed the window to write it was going to be brief, and it was.

FWR: How long did it take to write the book? Are you working on anything now, and, if so, does it speak to Reveille in any particular way?

LH: I wrote most of it in 6 months and revised for another 6 months, but this fruitful year came after 2 years of… maybe a different kind of fruit. Just learning. The poems I’m working on now are less narrative, less sequential. More imaginary. An image and a phrase will arrive as a pair and I find out how they know each other. Some of their forms are new to me, too. The Reveille years had a theme color and it was yellow—even though yellow is a happy color and that was a sorrowful time.

Now, I’m rejoicing, I have a baby, and the prevailing color of the poems is purple. I think purple and see a forbidden forest. I was puzzling over this last spring and noticed that for a few weeks, there were just dandelions in the grass, then violets appeared among the dandelions. It’s just the natural sequence. One follows the other, they go together. So, maybe the connection between my yellow and purple poems is as simple as that.

SEPTEMBER INTERVIEW with Julia Thacker

Julia Thacker’s debut collection To Wildness was recently awarded the Anthony Hecht prize by Paul Muldoon. The book makes its way through the wilds of New England, grieving the family born and buried there. To Wildness is enamored with the world of sense, yet lingers close to the realm of the dead. It is elegiac, yet fiercely vital, prizes holiness as much as irreverence. It brings all of these loves to life through exacting, brilliant language.

Julia Thacker was published in Issue 26 of Four Way Review and is interviewed here by Amery Smith.

FWR: To start – To Wildness is your first book, but it’s also (as you mention in an essay you wrote for Women Writers, Women’s Books) the first sustained bit of poetry writing you’ve done since grad school. What do you think you learned about yourself as a poet after finishing the book, and returning to poetry after so long? What differences (craft, writing philosophy, etc.) have you noticed between “MFA Julia” and “To Wildness Julia”?

JT: My return to poetry was entirely intuitive. The desire to reengage with the genre simply came over me like a fever. What became clear to me at the outset was that as a mature person, I had access to a voice with more tonal range. As a young writer, I’d recognized that my poems, though well-written, were stilted by what I’ll call their “high seriousness.” Then and now, I admired the work of Denis Johnson, especially his collection The Incognito Lounge, which moves from a high register to the vernacular, from ironic to lyric to self-effacing in the course of a single poem. While few of us will ever hit those heights, as an older writer, I have access to a fluidity and range of tone I didn’t possess during my first go-round as a poet.

Completing this collection also confirmed for me that I am a miniaturist. For years, I wrote and published short stories in journals and magazines, and tried many times to weave these pieces into a full-length novel. When I picked up poetry again, I vowed not to quit until I’d published this book. Bringing To Wildness to fruition taught me I’m best suited to the short form across genre, and I’m fine with that. I learned to be true to myself.

FWR: When you say that “as an older writer, I have access to a fluidity and range of tone I didn’t possess during my first go-round as a poet,” what specifically about getting older do you feel gave you that tonal range?

JT: When I was young, I considered poetry the highest form of literature. I was intimidated by the genre. My early poems don’t reflect the wit and humor present in spoken language. Now, with a wide range of experiences behind me, I’m more at ease in juxtaposing lyric with the vernacular.

FWR: I wanted to ask you about To Wildness’s structure. Paul Muldoon praises the book’s four-part structure for its range, both thematic and formal. How did that structure emerge? What did you feel like the poems were telling you about how they wanted to be ordered?

JT: Indeed, as you suggest, I did listen to what the poems were telling me about how they wanted to be ordered. They are often smarter than I am, and I follow their lead. Most of the pieces in the first section were written early in the composition of the manuscript. They’re foundational. They establish the world of the book, its subject matter and elegiac stance. And in these initial pages I wanted a variety of styles and forms, a sense of surprise from poem to poem.

My work is dense with imagery. The Roman numerals announcing each of the four sections offer a pause, breathing room, the calm of white space. My hope is that each section stands as a unit with a distinct narrative and emotional arc. Part II is a six-page sequence in the guise of “notes” in fragments, each with a parenthetical title. The sequence depicts a mother/daughter relationship over a lifetime, but the chronology is fractured. The elliptical nature of this piece required a section of its own.

Part III of To Wildness further interrogates their themes and formal experiments in the previous two. Here, for instance, are what I call the “backwards” poems, with hard right hand margins and ragged left hand margins such that the lines seem to be floating on the page. Part IV is noisy with ghosts. Often referenced in previous sections, they come alive in this final suite, as though they’d been conjured.

To Wildness opens as the speaker is in late middle age. In the final poem of the book, she is a young woman living on Outer Cape Cod, a spit of land at the edge of an ocean, learning to be an artist. Over the course of the book, time is collapsed and fluid.

FWR: I think one powerful example of the many dichotomies To Wildness bridges lies in “Soul Wears a Crown of Milk Thistle”. We usually consider the soul to be the body’s direct opposite, separate from all the goods and bads we associate with embodiment. In “Soul Wears…Thistle,” though, the soul romps up and down the coast, isn’t afraid to get intimate or “vulgar” (“Washes her unmentionables / at the sink. Bleaches her mustache” and “swims in her drawers”), and — paradoxically — even has a body of its own (“Sand makes a dune of her body”). What led you to think about the soul in ways like this, in both this poem and in others throughout the book?

JT: I was brought up in the Southern Baptist church. My grandfather was a preacher whose dramatic and beautifully delivered sermons were something to behold. I am a secular humanist. And while I don’t subscribe to his system of belief, I am quite attached to the trappings of my childhood: the language of the King James Bible, the hymns, the paper fans decorated with reproductions of Biblical scenes and stapled to Popsicle sticks. The speaker in my poem “Doxology” declares “I am my own God, my own high priestess./Mine own book of timothy./… Protector of sayeth, goeth. It came to pass.”

My family was religious, but far from sanctimonious. They were hysterically funny. My mother, upon being promised she would one day take leave of her corporeal shell and ascend to Heaven in new form, a celestial body, said, “Well, I hope it’s a long, skinny one.” As for me, rather than thinking of the soul as a spiritual essence which requires redemption, I imagine her as independent and not at all well-behaved. In “Soul Wears…Thistle” she is free from the constraints of doctrine and social mores, free from the person to whom she is assigned. She lives as she pleases. I celebrate this world, this moment. What is more holy than wading in cranberry bogs or eating tomatoes off the vine?

FWR: The book switches effortlessly between prose and lineated poems, yet both succeed in using language spare and precise enough to close around the concrete or tangible. What do you think is the relationship between To Wildness’s prose poems and the other poems? What has writing prose poems taught you about line poems, and vice versa?

JT: Without lineation, a prose poem depends upon the sentence, its syntax, diction, rhythm and richness of language. There are writers I respect who don’t believe there is such a thing as a prose poem! I disagree. I’ve always been fascinated by that hybrid animal. One of my favorites is “Lavender Window Panes and White Curtains” by Juan Ramon Jimenez which I first read in a translation by Robert Bly. Here, metaphor, imagery and nuance are embedded in a tapestry of language which announces itself as a poem rather than a prose piece:

“I have been planting that heart for you in the ground beneath the magnolias that the panes reflect, so that each April the pink and white flowers and their odor will surprise the simple puritan women with their plain clothes, their noble look, and their pale gold hair, coming back at evening, quietly returning to their homes here in those calm spring hours that have made them homesick for earth.” *

I enjoy the challenge of varying the shape and form of my poems which are otherwise cohesive in their preoccupations and voice. In To Wildness, there are poems in couplets, tercets, sequences, lineated stanzas and of course the prose poems. Though they appear in various forms, they are all image-driven and in conversation with one another.

I don’t know that prose taught me much about writing poetry except perhaps how to sketch a character in a few strokes. Poetry, however, has informed my prose quite a bit in its particular use of language, concision and resonant detail. My story, “The Funeral of the Man Who Wasn’t Dead Yet” (AGNI 51), for instance, is image-driven and compressed with an attention to musicality.

*Selected Poems: Lorca and Jimenez, Chosen and Translated by Robert Bly (Beacon Press, 1973)

FWR: I also wanted to explore how To Wildness thinks about ghosts, especially as connected to grief. Mirroring how the book writes about the soul, To Wildness’s ghosts are surprisingly tangible. The ghosts populating the book’s final section find joy in working with their hands. They yearn for the fruits of the earth, and even taste them (“Aubade”) — in ways that mirror first-section poems where the living also do these things. I’ve pulled some lines from the first and fourth sections as a comparison:

To be elbow-deep in a barrel,

arms gloved crimson,

to make of simple labor

prayer…

……

Today we must work

with our hands until they are

no longer hands…

(excerpt from the poem “Plum Jam”)

Ribbed squash, king-pumpkin with its thick curling

stalk. Persimmons, verily orange and magenta, the weights

of sunsets in my hand. Egg-shaped plums shivering

on the conveyer belt.

….

Let me touch them as they pass.

Let me sweep up the shadows

of my boot prints and store them in a locked box.

(excerpt from the poem “Bag Boy Works Harder Now That He’s a Ghost ”)

What drew you to this way of thinking about the dead? Do you feel like it’s opened up new ways of thinking about (or even processing) grief?

JT: The way I think of the dead goes back to what my kin would call “my raising.” My family has deep roots in Harlan County, Kentucky. And they’re all great story tellers. My mother was raised in a series of coal mining camps, where my grandfather, Roscoe Douglas, was a crew foreman, and later a Baptist preacher. For them, life was precarious and death not uncommon. My great uncle Andrew, my grandfather’s beloved younger brother, was killed in a mine accident at 17. But even thirty years later, when I was a child, Andrew was constantly invoked, his movie idol looks, musical talent, the story of how after the slate fall that killed him, their sister went running through the camp to tell my grandfather before someone else got to him. Then she heard his voice a distance down the tram road and thought, “Well, Roscoe’s singing,” But as he got closer, she realized he was sobbing, and she couldn’t stand it, She hid behind a tree and stopped up her ears. That scene is as vivid to me as memory. My grandparents had eight daughters. One was stillborn. Another died of influenza as a toddler. Yet my grandmother always responded “eight” when asked how many children she had. Their names and the particulars around their losses were told and retold to us. My baby aunts. In the Upper South, Memorial Day is called Decoration Day when we carried picnic baskets, blankets to spread on the ground, and armloads and armloads of flowers to spruce up the family headstones.

In that culture, you might say the dead exist alongside the living. Storytelling is an act of devotion which allows us to process grief.

To Wildness contains so many references to ghosts that by the fourth and final section, it felt only right to embody them in all their eccentricities and desires, to give them voice. Some are benevolent and protective. Others are capricious troublemakers, like members of any extended family.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview, Monthly, Poetry

JUNE INTERVIEW WITH STEVEN ESPADA DAWSON

Late to the Search Party is the debut collection of Steven Espada Dawson, exploring the individual and precise depths papered over by common nouns like ‘grief’ and ‘family’. The elegiac collection delves into Dawson’s love and grief for his dying mother, the decades-long absence of his addict brother, and the absence of a father, with language that is clear and resonant as he explores the “gorgeous myth of childhood” and “how to make a family/ from just one man”.

FWR: One of the epigraphs (“A hole is nothing/ but what remains around it”) is a line from Matt Rasmussen’s collection Black Aperture, which focuses on the death of his brother. Late to the Search Party also names and circles around loss, specifically the death of your mother and the disappearance of your brother. In constructing their portraits, the reader also sees you and your loss, your grief, come into focus. This isn’t so much a question as acknowledging its effectiveness! But to turn it into a question: can you speak broadly about the development of the collection? Was the hope in structuring the collection in four parts to have these portraits in conversation?

SED: The two epigraphs that open the book—from Rasmussen’s Black Aperture and Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec—acknowledge the windows I climbed through to make my own book possible. I owe those poems and people so much. They helped shape the emotional landscape of my writing about my family. (Another special shoutout to Diana Khoi Nyugen’s huge and brilliant Ghost Of that was also a pillar of possibility for me.)

As you mention, Rasmussen’s book orbits his brother’s death by suicide. There are not many books about missing addict brothers (or at least I have not found them), but unfortunately there are many books written post suicide. I found myself gravitating a lot to those works because they carry with them a familiar grief and energy. You have these sudden disappearances with often a lot more questions than answers. Diaz’s first book always felt like a family reunion. It’s really a singular, strange feeling to love an addict. It’s easy to hate them and retreat into that certainty. It’s harder to complicate them and hold yourself in their world of uncertainty. Diaz has always showed me how to lean into that. I’m thinking about that quote from James Baldwin: “You think your pain is unique in the history of the world, and then you read.”

During my MFA I was taught to resist writing in fours because its formal stability tends to slow things down, and you’re often looking for modes of propulsion—especially in a longer format, like a book. I arranged the collection into four parts to mirror the elegy series and the title poem, but it’s also to slow things down—something that felt necessary when writing around two family members at the fringe of life and death. I wanted to hold time more carefully.

FWR: I was struck by your return to elegy throughout the collection, specifically the recurrent title of “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Brother’s Heart,” which at times is “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother’s Heart” and “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Heart.” Can you talk a bit about the genesis of those poems? Were they always meant to be in refraction with each other?

SED: I started writing those poems after the shape of a book felt possible, and I needed a throughline to thread the disparate sections, starting with “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother’s Heart,” then my brother’s heart and finally my heart. I resisted writing an elegy series for my father to mirror his absence in my/my speaker’s life, which to me serves to echo his silence.

The heart elegies were originally published as single poems in four sections, similar to the title poem “Late to the Search Party.” I broke them apart after a recommendation from Eloisa Amezcua, one of my first readers. I was always struck by the way José Olivarez separated “A Mexican Dreams of Heaven” in his debut collection Citizen Illegal.

After separating the sections into their individual poems—with a lot of adjustments so that they stood on their own—I immediately felt like the whole thing was a lot more sustaining. For me, a series has a way of acting as a pulse check in a book. I wanted to tell the speaker and the reader “Hey, remember this? Don’t look away from it.” I wanted to capture the discomfort I felt while writing those poems.

FWR: Several of the poems return to your childhood, with a real tenderness, even as “nostalgia rends/ in absence”, as you write in “At the Arcade I Paint Your Footsteps”. How did you balance the (assumed conflicting) emotions as you delved into the past (with the knowledge of hindsight) and the uncertainty of the present?

To expand, I’m thinking of the poem “Lucky”, in which it’s revealed that the speaker’s brother has taken him to the dope house during a time when he’s meant to be babysitting. Despite the awareness of the speaker and narrator to the reality of the situation and the “guardian angel taking work naps/ among hallway sleeping bags”, the emotion I’m left with isn’t anger, but an understanding of the flaws in “someone’s idea of a hero.”

SED: When I first started writing poetry about my family, my experience of nostalgia was often split in two. It’s easier to come to terms with things when you can separate the good from the bad and take them in separately, one at a time like a DMV line. I think that can unintentionally flatten the reality, which is that (for so many of us) happiness threads itself through grief constantly, and vice versa. I think a project of this book is to bring those parts together and make a clearer picture of a more whole, honest reckoning.

I remember when I was young, and my brother asked my mom for $20 to take me to the arcade, then $20 for gas there and back. There was no car. We walked miles to the mall, looked at all the games but didn’t play them, then walked back. I understand that he took advantage of my mom and I. We did not have that money to spare, and he likely threw that cash into his addiction. I also understand that we spent real time together then, and he’d tell me stories about his life and the neighborhood, offer me the brotherly wisdom he thought might help me survive better than he did. Nostalgia can work that way. Insidiousness and sweetness share a bedroom wall.

FWR: There’s lots of touchpoints to nature in these poems, beginning with the first poem, “A River is a Body Running”. A poem like “Orchard”, which has all of this lush imagery used to articulate the growth and ravages of cancer really jumped out at me and reminded me of classical still life paintings, which always include an element of rot (a fly on the fruit, for example). Would you talk about how you brought in those elements of the pastoral?

SED: I grew up in a big city and was never afraid of loud traffic and big attitudes but was always nervous about the idea of a quiet forest, a sudden cliff, vast open water. I currently live on land pinched between two lakes, and it still terrifies me a little bit (see poem: “Lake Mendota, After Sunset”), but I’m getting better through exposure. (Though you will never catch me out on the frozen January lakes like so many of my neighbors.)

When you’re writing a book in places where nature is unavoidable, the flora and fauna and weather start to creep into your work. You’re taught to be a radical noticer, so everything starts to get vacuumed up into the same bucket. Suddenly the human entanglements filling in all the blank spaces become clearer. Heroin lives on the same page as opium poppies because they are fundamentally linked.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview, Poetry, Uncategorized

MAY INTERVIEW WITH SOPHIA TERAZAWA

When readers first meet the narrator of Sophia Terazawa’s novel, Tetra Nova, published by Deep Vellum Publishing in March, they have just been trampled by an elephant, returning to consciousness inside what seems to be the body of a panda. Soon after, the narrator tumbles again, this time awakening as Emi, a young girl with a backpack full of crayons that she must use to draw an exit from the chamber she has found herself in. Emi, as we soon learn, is not only Emi. She is also Chrysanthemum, her Vietnamese grandmother, and Lua Mater, a little-known Roman war goddess-turned-assassin-turned-performance artist—and she is here to guide you on Terazawa’s stunningly polyvocal, spectacularly non-linear journey through time, space, memory, and identity. (Non-linear, as in: the novel’s Table of Contents can be found nearly a third of the way through the text, on page 95.)

Expanding the bounds of what a novel can do, Tetra Nova reads like a dream journal written by a poet who is also a performance artist moonlighting as a translator excavating generational trauma. Plus, there’s a panda named Panda.

Sophia Terazawa is interviewed by E Ce Miller.

FWR: The form and structure that Tetra Nova takes are mind-bending. The agility with which you move readers through literal millennia of space and time, sometimes in a single paragraph, cannot be overstated. In your writing process, how do form/structure and content develop—do you find that your material naturally lends itself to a particular shape, or do you set out to navigate your characters through a non-linear, multi-form narrative from the start?

ST: Oh, thank you for opening with such a generous question! My mind bends continuously. It’s unnatural and natural both, this material that becomes a long hall of mirrors around all of my books. For Tetra Nova, the process arrived as one might now attempt to describe the occasion of a fractal: fern, snowflake, Golden Ratio… I don’t know where to land next with its momentum, but the “multi-form narrative,” as you’ve aptly picked up, is a great place to start. And maybe opera, too… In the shower lately, I’ve been practicing a karaoke rendition of “O mio babbino caro” with full range and emotion!

Okay, did I set about shepherding the characters through their marked spots of entry and exit? With this question, I think of Viewpoints by Anne Bogart and Tina Landau, on “soft focus” required of performers to navigate the span of a stage or “grid” with imaginary lines and topographies. How it felt for me: voices moving along this grid at varying rhythms and slants, a sequence of vertical and horizontal trajectories, a philosophy of lunges along the metaphysical plane, [See: Illustration by Robert Faires for The Austin Chronicle], and, of course, mosaic time. I really did have a film camera in my eye!

FWR: I’m curious about whether/how you relate to the (typically Western, North American) resistance to non-linear plots. It’s a curious resistance, at least in my mind, because it seems non-linear is precisely how most minds work. So much of our lives are spent in memory, anticipation, imagination, distraction, intrusive thoughts, etc., most of us are traversing massive expanses of time and space all day long, and yet there is somehow a rejection of that when it comes to storytelling. What did this nonlinearity allow you to explore as a writer that a linear plot might not have?

ST: Memory makes more sense for me in the dream world, especially without language. Here, cities often occupy my subconscious—nameless cities, cities at night… If the poetic impulse, more specifically an aubade, is awakening with relative shock or ecstasy to some wild, unknowable Truth, it’s our morning bird song. It’s a lantern for dawn. It’s the act of recalling: “I remember you. I remember how it felt to be loved by you, just yesterday.” And this becomes a triumphant return after the long exile of desire. Yes, memory as anticipation…

With this logic, on the other hand, I think about prose in terms of a nocturne, which in turn leads to the promise of silence: “I leave the soprano aria of you behind. I accept that you will never return. I close my eyes. No, goodbye. Let me sleep.”

Ultimately, nonlinearity arrives at such promises of memory’s obliteration. Thinking too much about Tetra Nova in terms of day or night, however, makes me want to murmur about Eden: “Please don’t wake me in this burning garden.”

Or maybe to Eros: “Where have you been? I’ve been waiting for your touch my whole life.”

Lulled to further abstraction… Perhaps the intersecting plots of my novel don’t want to say anything in the end. Only suspension… Finally, I think of John Cage who referred to Duchamp’s assertion of music as “space art” rather than “time art,” perhaps a fractional equation of space divisible by time, or perhaps laughter that doesn’t require meaning. Laughing is just laughing! I’m happy for our gift of forgetfulness.

FWR: Naming is crucial to this book. The characters frequently announce themselves by name. The refrain, “My name is Lua,” is repeated many times. At one point, Chrysanthemum, upon arriving as a refugee in Michigan, says, “Yes, my name is whatever you want.” You also write: “As I write through the multiplicity of what is possible or not, my name becomes whoever is reading this, yours.” I’m interested in any thoughts you might have on the significance of naming: what it is for a character to declare their name, what it is for them to give that naming over to something outside of themselves, etc.

ST: Lacan! The mirror stage! [Laughs.] The unified self and “Coronus, the Terminator” by Flying Lotus…

The scene in Bergman’s Persona, where the doctor observes about the actress, Elisabet: “The impossible dream… not of seeming, but of being…”

The unnamed dead of my mother’s country, which no longer exists in the Real of her imaginary…

The refrain of Mahmoud Darwish’s eternal banishment: “Write down: I am an Arab…”

The lines of lament merging between Vietnam and Palestine…

To declare a name, then, as June Jordan declared her stakes through poetry, mirrors the significance of becoming human and not simply seeming human amidst the smoke and mirrors.

My mind is ignorant in many ways, but around these meeting points of justice, I’m firmly planted alongside a collective life force within multitudes of mortal dignity. And what I fail to articulate clearly with this reply can be summarized, perhaps at the very least, with an assertion that Tetra Nova is my Name. And it’s your Name, too, if you allow it. Strange, the declaration of these names across time loops back to my mother’s name and your mother’s name. Hence, the force launches time across immeasurable distances. Hence, the astral plane of travel! Wow! Let’s go!

FWR: Much of the polyvocality of Tetra Nova is contained within a single character who is Lua, Chrysanthemum, Emi, and occasionally others. At one point in the novel, this character says, “I started to have a nagging feeling that the voices between my grandmother, Chrysanthemum, and my mother, Emi, were merging with mine.” I’ve heard that every mother/daughter story is a circle. Thoughts?

ST: Yes, circles are bisected by lines as well. A plot point compels the sweep of a body in angles of Vitruvius, and architectures of thought collide with architectures of narration. [See: Illustration by Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara, prefiguring Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Source: Ten Books on Architecture, Smithsonian.] Okay, let me try to reinterpret this in another way.

The square is set within its circle. Within the shapes are the rules of stage design. Within this design exists an elemental inscription of forces—wind, water, fire, earth—guiding the four corners of our planet back toward the center. The swordsmen of my father’s side, in The Book of Five Rings, might argue for our fifth element: Void, or the ether.

But I’m a simple thing with simple aspirations. Instead, I prefer melodramatic love scenes like the final declarative between Leeloo and Korben Dallas in the temple chamber of their heart, Mother and Father anchoring our profane and four-cornered worlds.

Watching this aforementioned scene had pushed me enough to orbit around the topic, and with a story, bickering between Aristotle’s concept of “potential infinite” and paradoxes of “actual infinite” compelling all points to wiggle. Love! Love! We want to shout.

FWR: Expanding on that question: At one point, readers are given the case notes from a technician at an institution where Emi is a patient. I’m curious how you think about this pathologizing of the polyvocal?

ST: Alright, so, in one of the hospitals of my past, I remember singing ALL of the time. It was insufferable; I was sorry for the revolving cast of staff and roommates. It couldn’t be stopped. And I remember eating a lot of cheese sticks during snack breaks. And I remember that somewhere amidst these iterations of asylum, Panda had been taken away at some point, as some sort of punishment. This made me Mad!

Therefore, what does the institutionalized memory say about pathology? I don’t think of “right” or “wrong” at this juncture because my commitment to the performance art kept us busy over those four extended residencies. We had roles to play and stage notes to take. It was a very serious time.

FWR: You write of the Vietnamese language: “…there is a word for unrequited love as a consequence of war through foreign dominance…” which is a line that just knocked me sideways. You also note that Vietnamese only has a present tense. In one of Tetra Nova’s “Citations,” you write of a photographer considering the D.C. Vietnam War memorial, quoting, “remembering does not come easily to Americans.” How do you relate memory and language? Do you think there is a quality to specific languages that makes their speakers more inclined to remember? Do particular languages lend themselves more easily to forgetting?

ST: I forget the best in English. My best self is in dancing. I’m inclined to feel that speakers know the gesture of a word before its utterance. As we move sideways, I invite us to return to the song, “In This Shirt” by The Irrepressibles, which had been played on a loop for the entire duration of composing Tetra Nova. And to the language of Complete Want, yes, the tonal mode of speaking inclines me more toward memory. It’s much easier to carry a melody in Vietnamese than in English. In Japanese, a syncopated rhythm is likened to cicadas… The best dreams are the ones in which I wake up singing.

FWR: There is also a point in your writing where the game Tetris and the English language are described similarly. If English is Tetris, what is Vietnamese? What about Japanese?

ST: Without English, time loses its container for me. To that point, Tetris has a start and stop point, much like spoken time. But neither Vietnamese nor Japanese operates like a game in my body. Marigolds perhaps come closest.

FWR: One of the central consciousnesses in Tetra Nova is Lua, this relatively unknown Roman war goddess who collected weapons captured from enemy combatants. Do you see language as one of these “captured weapons”? Is that something you ever consider as you write?

ST: Hmm, how spicy! A fabulous question! It is said that a mountain burns with the “elixir of immortality” by order of the Emperor, who is heartsick for the Moon Princess. This tale can be retold in numerous ways, including a version from my father, who recounted Kaguya’s journey for me as a child. He had been trying to explain the occasion of witnessing my birth without calling me by another boy’s name. Did he wish for my mother to name me Frederick instead? Did he wish for a minor god? I don’t know. But he had a story about me being born with a little monkey’s tail. The little tail fell off shortly after my earthly entrance, he alleged. Additionally, it was rare to hear me cry as a baby. Things were always falling off of me, I guess.

Lua, then, is she an “alter” personality? Calling back to your gentle concern about the “pathologizing of the polyvocal,” I can see connective tissues forming around a multiplied consciousness, the expansive Borgesian Library of Babel, and the bright hexagonal figure slowly taking shape. But I’m only still with the number four!

Oh, it now occurs to me in further overlapping shapes… Let’s see… If the artist’s work originates from a three-cornered plane, as Natsume Soseki ventured to paint, the written story gains its language through an additional angle, therefore moving toward the square of prose. Thus, ascending or descending toward the six-cornered form inches closer to a circle! Alright, so this hexagon is a ritual form. The pyre! [Laughs.]

FWR: In a LitHub essay, you wrote that you are the child of a parent raised by someone who had been a prisoner of war. I am also, and stories were told frequently about that family history when I was growing up. Of course, what was told, what wasn’t told, what became told differently over time, and the purpose of the telling all evolved and took on new forms as I grew older. It’s a story that, on some level, I think will continually evolve as long as I continue to consider it. I mention this because there are moments in Tetra Nova when the torture of women during the Vietnam War is recreated as performance art. At many points in the novel, it seems like performance is a vehicle for re-storying, if you will, for moving a story in all directions in time. Your characters are simultaneously ancestors and descendants; their stories are told and reimagined. You are also a performer—how do you articulate the relationship between your writing and performance art? Do you think there can be a restorative quality to telling, retelling/performing, and re-performing?

ST: Please let me share the full-hour performance of Tetra Nova, featuring the Roanoke Ballet Theatre. I hope this explains everything.

FWR: The jacket copy for Tetra Nova describes Lua and Emi as “embodied memory traveling across the English language.” How do you understand this concept of embodied memory? It strikes me as an interesting framing of what it means to be a being existing in time—are we all, for better or worse, really embodied memories? What does it mean to live as an embodied memory?

ST: One flaw in my mechanical design, among many flaws, is that I suffer from terrible motion sickness. If it weren’t for this stomach, I would have pursued as a young adult in this incarnation, in addition to studying divine geometry, a career in space travel. Strap me in! Shoot me up! Enjoy this illustrious life.

Alas, here we are… Yes, as you say, for better or for worse, the memory in a bottle rocket travels along a parabolic arc around the planet’s gravitational pull. Do you remember the seven comets passing by that night? I can only remember four. [See: Illustration by an unknown hand. Source: Mawangdui tomb, Hunan Province Museum]

FWR: I would be remiss, I think, if I didn’t offer an opportunity to discuss Panda directly. I often experienced Panda as an opportunity to indulge in some levity, in some whimsy, within this very charged, cerebral hurricane of a novel. I also experienced Panda as a very grounding presence. Who is Panda? (I see Panda also manages your website.) How do you hope readers experience Panda?

ST: Yay! With his consent, here’s a photo of Panda during the early part of his political endeavors. Thank you so much for speaking with us! This was a lot of fun!

[Photo of Panda by Sophia Terazawa]

- Published in Featured Fiction, home, Interview

FEBRUARY MONTHLY: INTERVIEW with CLAIRE HOPPLE

From the first sentence of Claire Hopple’s latest novel, Take It Personally, you know you’re in for a ride—in this specific case, you’re sidecar to Tori, who has just been hired by a mysterious and unnamed entity to trail a famous diarist. Famous locally, at least. What sort of locality produces a “famous diarist”? One whose demonym also includes the nearly equally renowned Bruce, made so for his reputation of operating his leaf blower in the nude, of course. And that’s just the beginning. Take It Personally follows Tori as she follows the diarist, Bianca, determined to discover whether her writings are authentic or a work of fiction. At least, until Tori has to go on a national tour with her rock band, Rhonda & the Sandwich Artists, who are, as Tori explains, right at the cusp of fame. It is a novel as fun as it is tender, filled with characters whose absurdity only makes them more sincere.

Claire Hopple is interviewed by E. Ce Miller.

*

FWR: It seems like much of your work begins with absurd premises. The first line of Take It Personally is, “Unbeknownst to everyone, I am hired to follow a famous diarist.” This quality is what first drew me to your fiction, this sort of unabashed absurdity. But then you drop these lines that are absolutely disarmingly hilarious. You’re such a funny writer—do you think of yourself as a funny writer? What are you doing with humor?

CH: Thank you! That is too kind. I’m not sure I think of myself as a funny writer, or even a writer at all––more like possessed to play with words by this inner, unseen force. But I think humor should be about amusing yourself first and foremost. If other people “get it,” then that’s a bonus, and it means you’re automatically friends.

FWR: In Take It Personally, as well as the story we published last year in Four Way Review, “Fall For It”, many of your characters have this grunge-meets-whimsy quality about them. They seem to have a lot of free time in a way that makes me overly aware of how poorly I use my own free time. They meander. They follow what catches their attention. They are often, if not explicitly aimless, driven by impulses and motivations that I think are inexplicable to anyone but them. They seem incredibly present in their immediate surroundings in a way that feels effortless—I don’t know if any of them would actually think of themselves as present in that modern, Western-mindfulness way; they just are. In all these qualities, your characters feel like they’re of another time—unscheduled, unbeholden to technology. Perhaps a recent time, but one that sort of feels gone forever. Am I perceiving this correctly? Can you talk about what you’re doing with these ideas?

CH: I’ve never really thought about them that way, but I think you’re right. And I think my favorite books, movies, and shows all do that. We’re so compelled to fill our time, to make the most use out of every second, and it just drains us. There’s a concept I heard about recreation being re-creation, as in creating something through leisure in such a way that’s healing to your mind. We could all stand to do that more. Hopefully these characters can be models to us. I know I need that. But reading is an act of slowing down and an act of filling our overstimulated brains; it’s somehow both. So maybe it’s just a little bit dangerous in that sense.

FWR: Are you interested in ideas of reliable versus unreliable narrators, and if so, where does Tori fall on that spectrum? She’s a narrator presenting these very specific and sometimes off-the-wall observations in matter-of-fact ways. I’m thinking of moments like when Tori’s waiting for the diarist’s husband to fall in love with her, as though this is an entirely forgone conclusion, or the sort of conspiratorial paranoia she has around the Neighborhood Watch. She also “breaks that fourth wall” by addressing the reader several times throughout the book. What are we to make of her in terms of how much we can trust her presentation of things? What does she make of herself? Does it matter if we can trust Tori—and by trust, I suppose I mean take her literally, although those aren’t really the same at all? Do you want your readers to?

CH: All narrators seem unreliable to me. I don’t think too much about it because humans are flawed. They can’t see everything. For an author to assume that they can, even through third-person narrative, achieve total omniscience in any kind of authentic voice seems a little bit ridiculous. But I’m not saying to avoid the third person, just to not take ourselves too seriously. I hope that readers can find Tori relatable through her skewed perspective. She views the world from angles that give her the confidence to continue existing. They don’t have to be true in order to work, and I think a lot of people are operating from a similar mindset, whether they realize it or not. We can trust her because she’s like us, even––and maybe especially––because she’s not telling the whole truth.

FWR: Take It Personally is a novel I had so much fun inside. I read it in one sitting, and when I was finished, I couldn’t believe I was done hanging out with Tori. From reading your work, it seems you’re having the time of your life. Is writing your fiction as good a time as reading it is?

CH: It means so much to me that you would say that. Seriously, thank you. Yes! Reading and writing should be fun. I’m always confused by writers who complain about writing. If they don’t like it, maybe try another hobby? I secretly love that nobody can make money as a writer in our time because it means writing has to be a passionate compulsion for you in order for you to continue.

FWR: You’re the fiction editor of a literary magazine, XRAY. Does your editing work inform your writing and publishing life? How do you see the role of lit mags in this whole literary ecosystem we’re all trying to exist in?

CH: Lit mags are crucial. They’re some semblance of external validation, which everyone craves. But what we’re doing, whether intentionally or unintentionally, is creating a community. We’re only helping each other and ourselves at the same time.

FWR: It is a strange time to be a writer—or a person, for that matter. (Although, has this ever not been the case?) As we’re holding this interview, parts of the West Coast of the United States are actively burning to the ground. Other parts of the country are or have very recently been without water. I know you directly witnessed the climate disaster of Hurricane Helene last year, which devastated many beloved communities in the mid-Atlantic, including the wonderfully art-filled city of Asheville. How are you making space for your writing in all this? How are you able to hold onto your creativity amid so many other demands competing for time and attention?

CH: Completely agree with you here. Things are a mess. Our climate is barely hanging on. There were several weeks where I couldn’t really read or write at all; the whole thing felt like some ludicrous luxury. I was flushing toilets with buckets of creek water. But now that my head has finally cleared, I’m able to realize their importance again. Great suffering has always produced great art and hopefully points us to a better way of living. It just might take time, recovery, patience, and perspective to develop that. Some of my favorite paintings and books were a direct result of artists’ personal experiences at the bombing of Dresden in WWII. How weird is that? We have to make time for art, but not in some sort of shrewd drill sergeant kind of way. We have to fight for it, make space for it, recognize that it’s just as important as whatever else is on the calendar. Recognize that it’s a form of therapy. And we have to feel so compelled to create that it’s happening whether we even want it to or not.

- Published in Featured Fiction, home, Interview, Monthly

JANUARY MONTHLY: INTERVIEW WITH MARIA ZOCCOLA

Any reader with even a cursory understanding of Greek mythology will recognize her name: Helen of Troy—daughter of Zeus, the most beautiful woman in the world, a “face that launched a thousand [war]ships.” Now take that image and fast forward about, oh, 3200 years, and you get Maria Zoccola’s raised fist of a debut, Helen of Troy, 1993. Through Zoccola’s poetry, Helen is transformed from ancient myth into mid-1990s housewife, from Greek goddess to American mother: dissatisfied, disgruntled, and viscerally relatable. It is a collection as unruly as it is beautiful, named a Most-Anticipated Book of 2025 by Debutiful.

Maria Zoccola is interviewed by E. Ce Miller.

*

FWR: This collection has all these layers of time: a character of Mycenaean Greek origin, reoriented in 1993 in the southern United States, speaking to English-language readers in 2025. Can you talk a bit about your process of navigating time as you reimagined Helen’s story? Why 1993, specifically?

MZ: I considered time constantly while writing this book, because every layer of that time machine (1200 BC, AD 1993, AD 2025) had to be intentional. It was a question, for me, of bringing Helen out of a hazy and indistinct past—Bronze Age Greece, more than three thousand years ago—and into a past that still felt crisp around the edges. I knew as I was writing those first few poems that I was entering the world of my childhood (or in fact, slightly before my childhood) in 1990s Tennessee, but I didn’t initially have a target year in mind. I quickly realized, however, that true precision in the detail work of the poems, real-life accuracy with elements like newspaper headlines, cereal choices, even popular fingernail polishes, would be a much more successful tool than the kind of generic nostalgia that’s easy to lean into with a story set in the nineties and eighties and seventies. For accurate research, I needed to lock myself into a specific timeline: when was Helen born? What year did she get married? What year was Hermione born? What year was my end point, when she returns from her affair with Paris and reexamines the life she’s living? I started there, with my end point: 1993, my own birth year, which was a little joke I had with myself while writing. Once I had my timeline rolled out, research became much easier, and the pieces of the book seemed to fall into place.

FWR: The title of the poem “helen of troy’s new whirlpool washing machine” really got to me. You’ve taken a woman so storied and mythical that her name has been remembered for thousands of years and given her a Whirlpool—she’s the most beautiful woman of all time, and it still doesn’t save her from the Whirlpool. Then, in the poem, Helen is sort of going on about the domestic bliss of this new washing machine…

sears & roebuck blazed down

the street double quick to black-bag broke betsy and wizard up a machine

straight from the cave of wonders i mean factory fresh six cycles two speeds

spin like a star trek thingamajig is it good enough for you helen what a thing

to ask as if i don’t crank the dial ten times a day just to watch the foam and

when she really gets up and running doesn’t she just suck out the stains—

(excerpt from the poem “helen of troy’s new whirlpool washing machine”)

I’m interested in what you’re doing here, whether readers are to take her words at face value, or is she messing with us a little bit? The next thing we immediately find out is that she’s been having this affair. So, all is not well in Sparta, as some of Helen’s words in this poem might indicate.

MZ: She’s the most beautiful woman of all time, and it still doesn’t save her—from anything. In the Iliad, what do we see Helen doing, when she’s allowed to have a presence and lines at all? Weaving, endlessly, the way good noble girls are meant to do. Her beauty allows her to escape death in the Trojan War, but nothing else: she is still entirely dependent on the men around her, tied hand and foot by the social conventions that prescribe her daily actions and scope of influence. In 1993, therefore, she is still washing clothes and dishes and cars and children, but she’s doing it, I think, in the same way Helen of 1200 BC is sitting in her Trojan chambers and weaving that tapestry: partially as a way of saying see? I can be good, I can do what’s right, despite everything, despite what’s inside me. (There is more to say about that tapestry, a textile masterwork, a history of the Trojan War Helen is creating in real time, but I’ll leave that for the Classics scholars.)

Helen is desperately unhappy in 1993. There’s a hole within her. She’s casting around for anything that will fill her up, anything that will anchor her down, and performing domesticity is one part of that searching (are there parallels, here, to the rise of the online tradwives in our current decade?). Embarking on an affair is another piece, another experimental avenue she walks down. And, both separately and connectedly, in “helen of troy’s new whirlpool washing machine,” the washing machine in question is of course a metaphor. Helen may be the most famously beautiful woman of all time, but she also has the world’s most famously stained reputation. She’s the ultimate fallen woman. In 1993, after that affair, she’s looking to wash out those stains. She’s produced a lot of dirty laundry, and she wants it clean.

FWR: In “another thing about the affair,” there’s this moment when Helen realizes she can’t discern her own child from all the other children crammed into the school bus, and she says that once she stopped trying to spot her daughter, she “just stop[ped] trying / on everything else.” Correct me if I’m wrong, but it feels like this instant when her child suddenly seems very far away from her, like she’s sort of individuated for the first time. I think there’s this moment in many mothers’ lives when the clarity of your child taking on a life of their own forces you to revisit your own life in a way you maybe haven’t in those immediate years after giving birth… So much loss can be realized in that slow return to oneself, right?

MZ: Helen’s relationship with her daughter, Hermione, was one of the fascinations for me in this collection. In mythological accounts, Helen is often given only one child, her daughter (though some writers record her as having sons with Menelaus and/or Paris as well). For a woman in Ancient Greece, a time before modern birth control and in which girls married in their early teens, having only one child is unusual, curious. Hermione herself was held in ancient sources to be very beautiful, though not nearly as beautiful as her mother. And in the myth cycle of the Trojan War, Helen leaves Hermione behind when she is taken (by force or by choice) to Troy; they are separated for ten years. Hermione is rarely mentioned in the Iliad. What, then, is Helen’s relationship to Hermione in mythology? Does she deeply love her daughter, or is Hermione simply something that happened to Helen’s body for the first and last time?

I reckoned with these questions in Helen of Troy, 1993. In my book, as in mythology, Helen has Hermione young, likely before she is really ready to be a parent. She struggles to understand and accept the pregnancy and birth, and ultimately years later calls herself “somewhat of an indifferent mother,” which I think may be accurate. She leaves Hermione behind seemingly without a second thought when she chooses to escape into an affair with Paris, quitting Sparta entirely for many weeks. And yet there are moments in which Helen feels her whole soul and fate to be bound up with Hermione’s, moments in which Helen may even surprise herself in how much she cares about Hermione’s happiness and future. Helen feels trapped in her roles as wife and mother, and yet there are times in which [an] awareness of Hermione as a whole and complete person, someone Helen created and is responsible for, pierces the fog blanketing Helen and wakes her up. I don’t think Helen and Hermione have a tight-knit relationship in 1993, but I do think Helen loves her daughter in her own imperfect way.