INTERVIEW with ROBIN LAMER RAHIJA

Robin LaMer Rahija‘s first full length collection, Inside Out Egg, was released in April. Ada Limón writes that “each poem contains the whole unbound strangeness of the human experience–the offhand remark, the blur of being in a body– all of this is written with a humility and understated wit that both growls and sings….” We were thrilled to interview Rahija about her process in crafting Inside Out Egg, as well as the development of this collection’s voice and the nature of the absurd– both in poetry and in the world around us.

FWR: Your poems conduct us into a theater of the absurd where you satirize our fears, our peculiar tendencies and our most ridiculous but touching attitudes. Your voice rings with audacity, and performance, as well as rebellion. When you say, “Something just feels wrong”— about our culture, our lives today, our attempts to find each other, the reader believes you. But, the tender, humorous way your poems express both the wrong and the small touches of “right” give us, your readers, both pleasure and hope in finding community.

I’m fascinated by the short poems that you’ve interspersed in your text that raise mind-boggling questions like “who’s to blame for this bad dream” and comment on the many uses of the preposition “for.” Did you conceive of them as breaks or respites, or did you have other thoughts about their place and placement in your book?

RR: Do you mean the Breaking News poems? The Breaking News poems I thought of as interruptions, like when we’re having a meaningful interaction with someone and the news app on the phone pings with something insignificant, or significant and horrifying, or stressful, and then the moment is gone. I wanted them heavy in the beginning and then to fade away as the book sort of settles into itself and the voice becomes more focused.

FWR: I think many writers and readers, including me, are interested in questions of process. Would you tell us a bit about your process—how a poem begins for you, if there are recognizable triggers; how you develop that initial impulse; how you revise, and so on.

RR: I think about this a lot. It might be different for every poet. It seems like magic every time it happens. Often it’s phonic. I’ll hear a phrase that sounds cool, and it will get stuck in my head like a song lyric. A friend of my told me a story about seeing a fox on the tarmac as they got on a plane, and I’ve been trying to work the phrase “tarmac fox” into a poem ever since. Other times it’s more about just noticing language doing something weird. I was watching the Derby the other day and a list of the horse names came up, which are always ridiculous: Mystik Dan, Catching Freedom, Domestic Product, Society Man. So now I’m thinking about a list poem of fake horse names, or what they’d name themselves, or what they’d name their humans if they raced humans for fun. The trick is training yourself to notice those moments, and also to note them down and not just ignore them.

FWR: Also, to my ear, you have a very strong, confident, even outspoken voice in your poems. One example that caught my ear is your title, “I Can Never Put a Bird in a Poem Because My Name is Robin” and “That Is Not Fair That” voice, to my ear, is quite brave, as well as funny. How did you develop that voice, or was it always natural to you?

RR: No, it’s definitely not my nature. I had to write my way into this voice. I started out writing language poetry that was just pretty sounds with no meaning. I was avoiding writing (and thinking about) the hard things. Writing for me has been a lot of chipping away at my own walls. Each poem too I think has to work on becoming that confident through revision. I don’t want my poems to be complaints. I want them to reveal something, but it can be a fine line. I’m a jangly bag of anxiety most of the time, and I think my poems reflect that. Writing is an attempt to make the jangles into more of a coherent song.

The humor is mostly accidental, I think. Or maybe it comes from an inability to take myself seriously. I do want to get the full range of human emotions out of poetry, and humor is a big part of how we get through the day.

FWR: Who are you reading now? And are the poets you read representative of anything you would describe as “contemporary”? Is there such a thing now? I’m thinking of Stephanie Burt’s essay describing recent poetry as “elliptical,“ meaning the poems depend on “[f]ragmentation, jumpiness, audacity; performance, grammatical oddity; rebellion, voice, some measure of closure.” Does any of this ring bells for you?

RR: I haven’t read that but it feels true for my work. I’m reading Indeterminate Inflorescence by Lee Seong-bok from Sublunary Editions right now. It’s a great collection of small snippets, like poetry aphorisms, that his students collected from his classes. I don’t know how I’d describe contemporary poetry, except it feels brutally personal and outwardly social at the same time.

AN ENGINE FOR UNDERSTANDING: AN INTERVIEW WITH Willie Lin

Willie Lin’s debut poetry collection, Conversations Among Stones, will be published in November 2023 by BOA Editions. Simone Menard-Irvine interviewed Lin for Four Way Review.

FWR: I would like to start out by first asking about what it’s like to be publishing your first full collection of poetry? What was the process of writing and assembling like in comparison to the publication of your earlier chapbooks?

WL: My urge in assembling manuscripts is always to pare down. Because of this impulse, assembling my chapbooks felt like a much clearer and more straightforward process. For the manuscript that became Conversation Among Stones, I struggled with holding it in its entirety in my mind and had to be more deliberate in my approach. I understood how certain constellations of poems fit together but was a bit overwhelmed with shaping the manuscript as a whole. At one point, I actually made a spreadsheet of all the poems that I thought might belong in the book and notated and ordered them according to a few different axes to help me see how they might fit together.

FWR: Your title, “Conversation Among Stones” brings up questions of action between the inanimate. What inspired you to frame your collection under this title?

WL: That idea is definitely part of what I had hoped to evoke with the title—of speaking to the inanimate and what can’t or refuses to speak back, of language spanning, filling, straining, or distending across gaps, of failing to say or hear what matters. I think these intimations are a good way of entering the book, which I hope worries and enacts some of these concerns regarding the capacities and limitations of language.

FWR: My next question is in regards to the variations of length in the poems. In “Dear,” which is only two lines, you write “A knife pares to learn what is flesh. / What is flesh.” Both a statement and a question, you ask the reader to consider something so simple, yet laden with ideas regarding the body and violence. What was your process in developing these shorter pieces, and how do you see them functioning within the broader collection?

WL: Poems can beguile in so many ways, but I’ve always loved the compactness of a short poem. Part of it is how easy it is to carry them with you in their entirety and turn them over in your mind. Since I first came across Issa’s “This world of dew / is a world of dew. / And yet… and yet…” in a poetry class almost 20 years ago, I’ve been able to carry it with me. I’ve learned and forgotten countless things in poems and in life in the ensuing years, but have kept that poem almost unconsciously, without effort. Another aspect of short poems’ appeal to me is the paradoxical way time works in them. A short poem’s effect feels almost instantaneous because of its brevity but time also dilates across its lines. The duration seems somehow mismatched with the time it takes to run your eyes along the text. In Lucille Clifton’s “why some people be mad at me sometimes,” the body of the poem answers the charge of the title in five short lines:

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine

That last one-word, monosyllabic line, especially, seems to take forever to conclude. The compression of the poem—the words under pressure from the wide sweep of white space—exerts a redoubled, outward pressure and reverberates.

My poem “Dear” started as a longer poem (not longer by much, maybe 10 lines or so). At one point, as an experiment, I took out all the “I” statements in the poem and arrived at the version that exists now. Often, that’s how it works. I try different approaches and revise, sometimes rashly and foolishly, until something jostles loose. When I finally got to the two-line version of “Dear,” for me, the fragmentary nature of it fit with the precarity of its assertion and question. How the shorter poems appear on the page also matters in that I wanted the blank expanse that follows the poem to function as an extended breath. Because the book proceeds with no section breaks, it made sense to me to vary the lengths and movements of the poems to establish a kind of cadence, a push-and-pull.

FWR: In thinking about the themes that circulate throughout your work, a couple of specific ideas stand out as particularly potent. One is the issue of memory; the violence, complexities, and confusion of your past run their threads throughout the collection. In “The Vocation,” you write, “In the year I learned / to cease writing about history / in the present tense, / I was the silence of chalk dust, / of brothers.”

It seems like history, for the speaker, is something to be dealt with, instead of accepted unquestioningly. What does writing about the past, be it in present tense or not, do for you as an individual? Does confronting the past through writing work as a catharsis, a way to process, or does it instead serve as a conduit to expanding upon the ideas you wish to convey?

WL: I think memory—and the process of remembering—is an engine for understanding and, by extension, meaning. For experience to make sense, we have to remember. Knowing or thinking can’t really be separated from experience. It’s also true that memory, personal and communal, is restless and malleable. I have an image of the past as a landscape of sand dunes. The shapes drift. They slip, they resettle. How things feel in the moment can be one kind of understanding, how we remember them, how they shift, linger, rise, how they appear in the context of things that have happened since or what we do not yet know are other kinds.

In Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay,” when challenged on why she remembers “too much”—“Why hold onto all that?”—the speaker responds, “Where can I put it down?” I suppose poetry for me is one place to put it down. (Though I don’t think I could be accused of remembering too much in life. I have a terrible memory.) In writing a poem, I’m making a deliberate attempt toward an understanding, however provisional. Poems are good spaces for holding and turning, for thinking through and imagining, for venturing out—and that is the final, extravagant goal, to reach out and connect with someone else. In my poems, I want to make a path that leads inward to the center—and out.

FWR: In that same poem, you confront another central theme: men. When you mention men, they are typically described via their participation in fatherhood or brotherhood. You write, “the men/slammed the table when they laughed/at their circumstance, or drank/too much to learn what it meant/to have a brother, or were true to/no end, or tried to love their fathers/before they disappeared into/hagiography.”

Masculinity here seems to be defined as a relational identity, one that is constituted by lineage and socialization. I would love to hear you speak on your relationship with gender norms and roles, especially in your writing.

WL: This question is particularly fascinating because I can’t say I conceived of my poems working together in this way, even though of course you’re right to point to how often these types of familial terms come up. I suppose part of the answer has to be how the poems relate to my autobiography. In my family, my mother is the only woman in her generation. She has two brothers and my father has two brothers. I’m also the only woman in my generation. I have three cousins, all men. I’m an only child who grew up in China during the one-child policy, so all around me were lots of children just like me, who’ll never know what it means to have a sibling. I felt a bit of an outsider’s fascination with those types of relationships and inheritances, especially as I got older and became more aware of the other social forces at work that historically favored sons. I think poetry can function partly as personal interventions in cultural history and memory, holding the ambivalences, contradictions, and idiosyncrasies that live at those intersections.

FWR: We see many instances of place in relation to memory, but there are only a few instances in which those locations are given a specific name, such as in “Teleology” when you mention Nebraska. Can you walk us through your approach to location in your work and what places need an identifier, versus places that can exist more specifically within the speaker’s domain of recollection?

WL: I think generally the idea of dislocation is more important than the locations themselves in terms of how they function in the poems. Saying the name of a place evinces a kind of ownership of or intimacy with that place. For many of the poems, in not naming specific locations, I more so wanted to evoke a sense of rootlessness and for the intimacy to be with the speaker’s uneasiness within or distance from those places. “Nebraska” in “Teleology” is a departure from that model not only because it offers a specific name but also because I think in this instance Nebraska is not a real place but an imagined one—a kind of projection that stands in for other things (the poem says, “like Nebraska,” “many Nebraskas,” “Nebraska is a little funeral”—my apologies to the real Nebraska!).

FWR: In “Dream with Omen,” you end the piece with “I would like to rest now / with my head in a warm lap.” This is one of my favorite lines, because it both speaks to the sound and feel of this collection, and it interrogates the two balancing aspects of this collection: that of memory and the mind, and that of the physical present. The speaker in many of your pieces seems to be constantly grappling with the subconscious world, made alive by dreams. How do you view or negotiate the separation and/or melding of the subconscious and the “real” world? Does the mind and its preoccupation with the past stop the self from fully engaging in the present? Can the speaker rest in a warm lap and still accept the darkness of the subconscious?

WL: In putting together this book, I became conscious of how often I write about dreaming and/or sleeping. I felt sheepish both because we are told often (as writers and as people) that dreams are boring and because maybe these poems betray my personal tendency toward indolence.

It’s interesting to align the past with the subconscious and the present with the “real” as you do in the question. I do feel the tension between those things in writing even as I also feel that thoughts are real and fears are real, etc., just as senses—how we experience the physical world—are real. And it feels a little silly to say this but I have a kind of faith that our subconscious is working away trying to help us come to terms with what occupies us in the real, present world even as we sleep and dream. Everyone who writes has at times had that sense that what they are writing is received, as if they are tapping into some other world or force. Maybe that idea is analogous to what I mean.

Memories, dreams, the subconscious, however the particularities of the mind manifest, feel consequential in their bearing on lived experience—they are how the real world lives in us. There is no unmediated world. Or if there is, we don’t know it. We must encounter the world personally because we are people. All this is to say I’m still learning line-to-line, poem-to-poem how best to articulate that kind of interiority in a meaningful way, without leaving the reader adrift. Leaning on dreams can make a poem feel muted and entering memories can feel like putting on the heaviness of a wet wool sweater and those things do not always serve the poem. I hope for my poems’ sake that I get that balance right more often than not.

Willie Lin was interviewed for Four Way Review by Simone Menard-Irvine.

Simone Menard-Irvine is a poet from Brooklyn, New York currently pursuing and English degree at Smith College. Her work has been published in HOBART and Emulate magazine.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview

FWR Monthly: September 2015

Meditation frequently asks its practitioners to ground themselves in their bodies through a series of structured “noticings.” You are gently urged to press yourself into your chair, press your feet into the floor, press your fingertips together, press your lungs out into their little cage of ribs.

It is easiest, it turns out, to notice your body when it meets with a measure of resistance. The floor is a fact your feet cannot change. To live in a body, we are told and retold, is to forget about this all the time.

When I solicited poems for this issue, I asked for work that “enacts or inscribes the feminine in fresh, unusual, or surprising ways.” Noting that gender is both inscribed upon the body and enacted by the body, I wanted to see how gender could visit the text, or the site of inscription. It is, in fact, near-impossible for many of us to forget about our bodies. This is not a failure to live within them, but a ricochet from resistance to resistance, reminder to reminder – “You do not inhabit this body. To the world’s eyes you are this body. Here is what that means.”

I’m delighted by the poems in this issue, in no small way because they make the original phrasing of my solicitation seem deeply small and beside the point. They embrace the mystic and the vulgar. They are funny, heartbroken, and kind. They dig deep for inner voice and reassemble the voices around them in a gorgeous echolalia. With plums. And hoofprints. And Kim Kardashian. I hope you like them.

Kate DeBolt

Assistant Poetry Editor

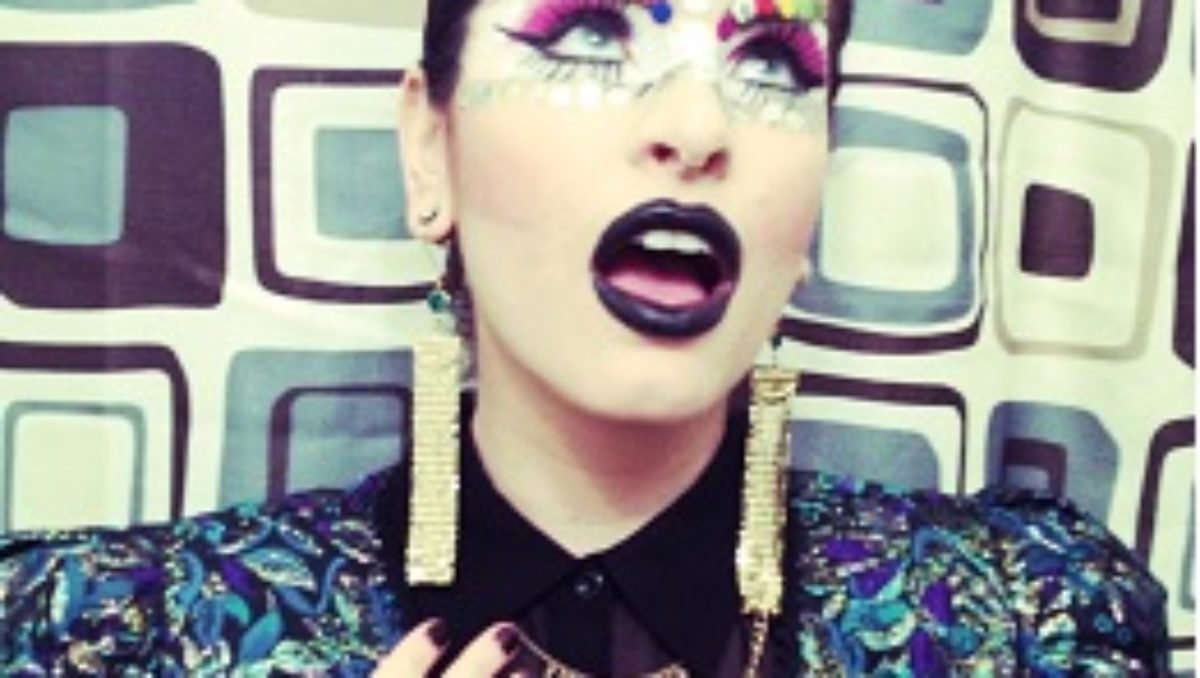

DRAG NOTES – FROM A CONVERSATION WITH KINGA

by Justin Engles

TWO POEMS

by Danielle Mitchell

THREE POEMS

by Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

PRAYER TO ST. MARTHA

by Leah Silvieus

Artwork by Lexi Braun

- Published in home, Monthly, Uncategorized

FWR Monthly: August 2015

The idea of voice has been hot on my mind lately. I think the ongoing work of folks like Amanda Johnston (one of the founders of Black Poets Speak Out), has made me think closely about how I move through the world, speak for myself, for and with others. Voice is subjective, relative. It’s also incredibly relational. Although I’m not a thousand percent behind Naomi Wolf’s talk of vocal fry, I know well the phenomenon of adapting one’s voice to suit one’s audience. The question is, then, from which conventions and collectives does one draw? And why? A writer performs on the page for a hypothetical audience, introducing herself to strangers again and again. Whatever voice that writer inhabits at any given time should be considered and relevant, and it should always feel true.

Since this is my first monthly curation of Four Way Review, the theme feels apt. As editors, we think about our own voices, our voices in conjunction with other editors’, and how the pieces we celebrate reflect upon us. Last month, Ken Chen, Executive Director of the phenomenal Asian American Writers Workshop, wrote an article excoriating certain white artists whose so-called transgressive work does little more than parrot the language of violence, racism, and patriarchy. Another recent editorial at Apogee raises the idea that it is as impossible – and unethical – to “read blind” as an editor as it is to be colorblind in the way we engage with each other in the flesh.

Here’s my secret: I was a little tempted to name this issue The Anti-Rachel Dolezal Life & Times, for the sake of those of us who have worked very hard to be ourselves, to own where we come from, and to make art from that space. The aforementioned – now-infamous – identity thief, who has worked with visual media in the past, was, unsurprisingly, once accused of plagiarizing a landscape by another painter. The appropriation of style, voice, and culture all converge so neatly in her story, it’s remarkable.

With all of this roiling in my head, I found myself, more than anything, wanting to read gorgeous, powerful voice. Just that. Inventive, not necessarily confessional, but representative of the artist in an elemental, charged way. When I started feeling tired of tired voices, avery r. young and Juliana Delgado Lopera came to my mind immediately, as the balm I wanted and needed most.

I bet you’re going to like reading these folks. Their styles are very different: young’s work boasts spareness and abbreviation, often using the architecture of parentheses to slow the reader, to encourage and reward re-reading. Lopera’s narrator, on the other hand, has fluidity and grace that’s enviable. Both are immediate. Neither backs down.

It wasn’t planned, but I don’t find it at all surprising that, in young’s suite of poems and Lopera’s excerpt, both use Christianity as a springboard for their characters’ voices. Owning one’s voice often comes from looking directly at structures of power, the stories we as a culture swear by. I think it’s important to reclaim power this way. And maybe it seems naïve, but I feel the connection between the art we make and support and the way we engage each other in the world is very real. These two artists are doing the good work.

~ Laura Swearingen-Steadwell

Poetry Editor

excerpt from FIEBRE TROPICAL

by Juliana Delgado Lopera

NEW TESTAMENT

by avery r. young

- Published in home, Monthly, Uncategorized

FWR Monthly: July 2015

For this installment of our new monthly “mini-issues,” I wanted to present a small folio on a genre which seems to gain more and more attention, particularly among poets — the “photo-essay.” Because so much of our daily life has gone digital, it becomes harder not to primarily encounter the world through our sense of sight. And “seeing” isn’t easy. For the photographer, when a photo essay is being built, he or she must whittle down, sometimes from hundreds of photos, until the image is found; then he or she must find other images that create tension with that original image. This month’s Monthly will present you with two poet/photographers, Chris Abani and Rachel Eliza Griffiths, both of whom I believe are doing fascinating and challenging work through photography. And please read the interview I conducted with Rachel! Such wonderful answers. That said, have a look-see (ha, see what I did there), and thank you for reading.

~ Nathan McClain

Poetry Editor

ON THE PHOTOGRAPH: AN INTERVIEW

with Rachel Eliza Griffiths

GHOSTING, INVISIBILITY AND THE ERASURE OF PARTICULAR BODIES: A SPELL

by Chris Abani

Ghosting, Invisibility and the Erasure of Particular Bodies: A Spell by Chris Abani

Introduction by Poetry Editor Nathan McClain:

At our 20th annual Cave Canem Retreat last week, I learned that a camera, no matter how good a camera, is mechanical. This sounds like a simple statement, I know, but what it means is that a camera doesn’t see what you see; a camera only sees what’s in front of it. A “good shot” isn’t on account of owning a good camera. Our role, as poet and/or photographer, is not only learning to “see,” but also learning to frame what you “see” (so the camera also sees). This practice requires a fundamental understanding of image which, in either a photograph or a poem, is, or should be, our primary focus. “Every poem is essentially an image” and, according to Chris Abani (who I’ll paraphrase in great detail here), who recently sat with me and discussed photography, and image in particular, “every image [as, I hope, you’ll see] is composed of three parts: a striking visual image (which occupies the focal point), movement (which creates depth of field) and sound.” (In a photograph, sound is always implied because you can’t hear it). Understand that when Abani references a photograph, he is differentiating between a “photograph” and a “snapshot” to which, in our current dispensation, we are constantly exposed. Hello, Snapchat. Hello, Instagram. A “snapshot” is an image that has no connection to us beyond the representation of the moment; it holds nothing beyond the materials of its composition. It’s anecdotal. A “photograph,” conversely, is never a representation of life, as that would cause the image to be static, flat. It’s an image that reveals the limits of its individual material components and reaches beyond the frame. The photograph, the poem, is about invoking presence. The self is (and should be) implicated. We try to find apertures which are closed, so we can open them. This creates empathy because, to paraphrase Baldwin, “your suffering means something only inasmuch as someone else can connect their suffering to yours.” Our trauma creates an aperture for someone else’s trauma.

Abani was kind enough to provide us with a small photo essay. Originally, when I considered the photo essay, I thought “argument,” but it’s really a conversation. Persuasion (or rhetoric) functions in that it limits the frame for you. Framing, or positioning, conveys intent. When a photo essay is built, one whittles down until the image is found, and then images that create tension with other images. Enough narrative is provided to engage a viewer, but enough lyric space is left so other narrative and emotional possibilities are available for the image. A viewer leans into it…

__________

*

Fair warning, I am a tatterdemalion.

*

*

As in all meditations around photographs, words must take second place to the image, which should hold all the profundity, as words are mere facsimiles of the actual. Nonetheless.

*

Women, embodied and alive resist inscription. Not in the sense of striving toward or against, but rather in the sense of presence: the state of being present, a fact of body and all that derives from it. Women ARE.

*

*

The masculine gaze attempts to temper women to desire, lust, hunger, and a need that makes men the center of the world. But women can’t be overwritten easily because we cannot overwrite what IS.

*

*

British sculptor Antony Gormely thinks of the human body as a “place of habitation.” He makes art by using his body, or the bodies of those who live in the areas his work will be shown. This art is a direct mold of their bodies, I think, in hope of locating how we inhabit bodies, since once the sculpture goes into the world, the audience inhabits them. This kind of site-specific installation is simultaneously mobile and resists easy inscription in this way.

*

*

The masculine drive to shape women’s bodies to desire and need, one that can be magically harnessed to any object in order to magnify its appeal, requires an evacuation first. This may seem counter-intuitive but it isn’t – to make a woman with large breasts hypersexual, or to make blonde hair signify stupidity, or to make glasses signify smartness is to transform women into mannequins, to remove the self. And since this is impossible the fabrication begins on the outside, a way of shaping perception such that even the self inhabiting the body questions her own understanding of it.

*

Seeing this window installation in LA I was drawn to the mannequins. Since the conceit was the future, it saddened me to see that even in the future, even in a post-apocalyptic world, women are still positioned within the masculine gaze. The reflected consumer products, one of them a cell phone company logo lodged firmly in one mannequin’s throat, seemed to indicate a silence. The skulls, usually associated with hunters and masculine prowess when mounted, were further signs of inscription. And yet, there is something about these mannequins that made me think of Antony Gormely and I realized that what had happened here, by a curious trick of the light, of seeing, was that I was compelled to seek habitation in these bodies, to find myself in them. There was something in their positioning that invoked their presence, the fact of them, the possibility of them, and the negation of the act of patriarchy.

*

*

But the images must speak for themselves. I am, in this regard a tatterdemalion, which is to say you must not take my word for it. I am after all, a man.

- Published in Series

ON THE PHOTOGRAPH: AN INTERVIEW with Rachel Eliza Griffiths

from FWR Poetry Editor Nathan McClain:

While at Cave Canem, I had the opportunity to chat with, and interview, poet and photographer Rachel Eliza Griffiths on the functionality and nature of photography and, more specifically, how aspects of the gaze and engagement contribute to a photo’s overall work. Her responses were far too wonderful and in-depth to distill, so I’ve provided Rachel Eliza’s responses, in their entirety, for your perusal. Rachel Eliza, too, provided us with a photo essay, which I’ve embedded in her response, as I sense the two are in conversation.

A poem, or a photograph, after it leaves you, is a virus that exists in the world. It replicates itself and, despite its framing, it cannot be contained. My hope is that Rachel Eliza’s photos and responses affect, or maybe more so infect, you…

NM: How would you say the photograph directs the gaze in a way the poem may not?

REG: I want to be careful to not make any sweeping statements, as your questions are so interesting and fluid to me. I’ll think of these questions for years. I admit that I feel the photographer in me resisting my efforts to verbalize or theorize the parts of me where my visual alphabet works in terms of imagination and politics. There is obviously as much nuance within photography and photographers as there is amongst poets and the tools/language they employ to shape, light, and to shadow their work. For me, there are shared spaces between imagery and vocabulary and other spaces where neither can help, witness, direct, or translate the other.

The presence of tension and intuition, whether in a poem or photograph, is critical for me in terms of process. When I think of process, I think of my body and of its systems. How I experience my body, as I am writing, is distinct from the sensations I experience when I’m using my camera. For both, landscape – where I am and with whom and where, the specific geography – becomes literal, internal, spectral, exterior. I don’t resist these contradictions. I get away from squares, unless they are pages or viewfinders. For a while, all shapes are doors, stairs, and windows. After photographing, I feel my work in my muscles, my back, hips, and arms. They’re sore. When I write I have to remember my body. I look up and hours may have passed without me even getting up for a glass of water.

In a photograph, I have to meet myself as an “I” in ways that I’m unable to articulate in a poem. But I don’t see this as a failure. The mood or space where tension exists comes from the same vulnerability, the same power. In a poem the “I” is working at something, so interior, that the photograph can barely perceive it, much less reveal it in its entirety to my own gaze.

For example, many of my self-portraits included here incorporate blurring. If I take an image of myself and I seem too still in it I feel as if I’m dead somehow. I get freaked out. Blurring helps me see how spiritual I am and reminds of how the past, present, and future can function in a two-dimensional portrait of one’s self. I don’t necessarily need narrative but I often like to sense movement in the environment, which is also living and moving.

When I’m looking at myself I’m hoping for discovery. I accept the outside and reject the outside. I accept the inside and reject the inside. I use language and I subvert language. Texture, color, light, shadow, frame/composition, sound, absence, voices, and faces become surrogates for what I cannot say. Recently I began to incorporate my body in photographs. That space is difficult to metastasize, or offer in my poems because of how freighted and unstable language can be. I think of alchemy, authority and permission, and how those relate to photographers and to poets. Sometimes I think of the gaze and I think about beauty and desire and violence. I think about how a poem about my body might be received if it were placed next to an image of my body. I try to let the work say it because the work knows it better and more honestly than grammar. People will say a photograph does not lie but, of course, photographs lie too.

But photographs and poems also become glyphs – they’re 2D. I’m not. I have to push at them, break them, to give them bones and flaws and flesh that can outlive me. There is a relationship that must happen immediately, structurally, thematically, and psychologically between the poet and the reader. Mortality happens between the poet and reader. The photograph itself happens immediately and then, if the photograph is strong enough, it will reverberate and live, sometimes hidden for years, inside of the gaze where it was first experienced.

Time in a photograph also splices and freezes an experience in a way that I feel a strong poem can also transform its reader. For example, consider the past and the future. I don’t know if the present tense exists in photographs but it does, often, in poems. When I invoke the past or the future in a poem I don’t see it with the same lifespan a photograph holds. Photographers can photograph or intuit the future but the implication of doing that almost goes against the common intention of most images, which are snapshots, which is to convey what Reality is/was like. With the “likeness” being accurate enough to the real. Being ‘accurate’ in a poem has little value or meaning unless it is part of the poem’s truth. It is easier for us to accept a photograph or dismiss it as, ‘that’s not real’ in a way that does not happen easily in a strong poem. Poems make us believe in ways that photographs aren’t necessarily concerned with – and this calls into light the places where the air thins between these ideas.

Our world is so visually conscious of itself. While certain types of cropping or manipulation, lack of credit, laws of fair use, etc. in a photograph can be egregious sites of outrage, manipulation in a photograph is usually not as averse to our reaction to feeling manipulated by a poet. Is there more at stake when we, in our roles as “readers”, are manipulated?

Most of the time we assume that the photograph we are seeing has been revised, edited. And a photographer is more likely to have a photograph plagiarized or appropriated (without much consequence) than a poem. Some photographers are okay with this because of how democracy, amongst photography, works in its contemporary republic. Most people would never quote or use a poet’s work without providing some attribution or credit. But photographers expect this and as such, there are photographers who make their living by selling ‘stock’ images. ‘Stock poetry’, wherever it appears, is usually derided. As viewers, we are more likely to be impressed and admire a skilled photographer’s manipulation of an image than we might necessarily be if we were to witness a certain type of cleverness or verbal pyrotechnics in a poet’s toolbox. We might be dismissive of that poet for being ‘experimental’ or ‘too much’ or find such dazzling attempts as distractions from the work itself.

There’s The Gaze too. I don’t have enough space to go into that! But reciprocity is part of this conversation. We must speak of what is private and public within the context of the gaze. What is authorized. What is banned. What is legislated and outlawed. Do we judge the photographer for immorality or ethical trespass in the same way we might apply such concepts to a poem or a poet? When a photographer has the opportunity to ‘take the shot’ (always this hyper-aggressive vocabulary of taking, shooting, capturing), what is at stake? What is at stake for a poet who gives voice to those who cannot speak? What is at stake for a photographer, who looks, makes visible the necessary moment, when the world will not see or would not see otherwise? What is at stake when the poet executes that identical gesture? How do we compare the notion of silence and speech when it occurs in either poem or photograph?

Depending on who is looking, the photographer is as much the object and subject as the production of the final image. For example, consider celebrity photographers whose celebrity will sometimes be noted and lauded before any actual attention is given to the work. I believe that this happens, but a bit differently, with poets. The notion of a photographer as ‘author’ can be as expansive as the poet’s task. But there are other elements to examine for both poet and photographer including accountability, anonymity, privilege, intention, politics, ethics, and of course, imagination. Again, it depends on the type of photographer. War photographers need different tools than underwater photographers or wedding photographers. I don’t have any judgment about this. I believe it’s about the way you feed your eyes, what you must look at and what you need to see and every wound of gray in between.

NM: Is there a way in which we engage with a photo that we do not with a poem?

REG: There are many ways! I think about this all of the time so I don’t have a static answer. We engage poems differently, even amongst ourselves, as readers of poetry. We assign value (and outrage) in dynamic terms when it comes to photography in ways we might not when we are reading. We engage photographs differently when they appear in museums, advertisements, family albums, or social media. Many of us are curating various narratives and lifelines with our ‘smart’ devices. There is also a global coherence that is happening now, irreversibly, because of technology. This is complicated, revolutionary, amazing, and dangerous.

If I read a poem written in English it possesses a distinct fluency because my first language is English. In which language(s) do we experience photographs? Many of my favorite photographers are not American. But how can you look at photograph and immediately discern its author’s identity or where that photographer is from? How does the concept of universality relate to a photograph beyond the image itself and for its own sake?

With poems, it’s interesting. If I’m reading a poem that was originally written in French, I’m likely to look at several translations or ask friends for suggestions for the most informed version. I’ll be looking for the best version, the closest version. I have to do more work because I want to experience the language of the poem as closely to its original text as possible. All translations are not equal but how would that notion manifest in photography?

Intimacy is also something I often think about in relationship to both poetry and photography. The intimacy I might share in a photograph is neither identical nor lateral to the intimacy I share in a poem. Both forms engage different threads of the gaze. These forms are often contradictory in relation to the acceptance or rejection of the gaze. The shapes of the gaze in either medium are relative to my content and intention. For me, any attempt to answer this question only provokes questions. Who is the We? How do we, as individuals and public citizens, understand, maintain, and define ‘literacy’? Personally, I’ve had numerous experiences where there is concerned.

Photography’s functions are not identical to poetry’s processes and forms. Perhaps poetry and photography are fraternal twins. If I look at a photographer’s work my dialogue with that work happens in a matter of seconds. I find an opening, a narrative (however fragmented or fractured), a visual seduction or rhythm, an emotion that is persistent. Visceral. I find what fails in its complete articulation to be verbal or knowable.

TWO POEMS by Sierra Golden

LIGHT BOAT

n. A small fishing boat equipped with several 1,000-watt light bulbs hung from aluminum shades to attract squid to commercial fishing grounds.

Jesse isn’t really a pirate, but the Coast Guard thinks so when he calls to say he found a body. It doesn’t matter that she’s still alive, so cold she stopped shivering, blue fat of her naked body waxy and blooming red patches where his hands grabbed and hauled her from the water. He stands over her with a filet knife, slowly honing the blade as he waits for Search and Rescue. The glassy eyes of a dead tuna stare up from the galley counter. At dusk, Jesse flicks on the squid lights. When the uniforms arrive, they question Jesse, but never tell him who she is. Taking her away, the Lifeboat’s white wake is brilliant in the night. Days later, Jesse reads the story of an obese woman slipping out of bed at Johnson Memorial. She shed a hospital issued flannel gown and left nothing more, not even a whisper of footprints on the white tile floor. Jesse lights up a mass of squid and imagines her bare bottom shining under the moon as she waltzed herself into the slate-gray ocean and floated away. He knows how she must have longed for the cradling dark. He watches ruddy bodies pulse in the artificial bright, the net dropping around them like a curtain.

NET WORK

Shuttles flick through diamond-shaped windows.

Just fingers flash, bending the twine in stair steps up and down cut edges.

Their pockets full of hooks and flagging tape, men mend the net.

Jim recalls branding cattle as a kid in North Dakota, winter cold just lifted,

calves struggling in mud before the prairie bloomed, withered in summer heat.

Playing cowboy now, he says he shot coyotes and Indians off his dad’s land.

Face deadly straight, you only know he’s lying when his fingers stutter,

stick, the tiny knot coming up slack. Just one unraveled compromises the delicate

lift and pull of meshes under stress. I’ve seen whole seams split from end to end.

He knows love knots pull tighter under pressure, stronger than the lines used to tie them.

He starts talking about his grandmother with Alzheimer’s. Each winter she thinks

every day for a week is Christmas. Last year she fell in two feet of snow.

Feeding the horses, hay in her hands, the wind at ten below, she lay crying

until Jim’s grandfather found her. She didn’t recognize him,

but knew love when it grabbed her, pushing back the terror.

Jim joins two lines with overhand knots, sliding them one on top of the other,

pulling for tension. Sometimes the line snaps in his swollen fingers. His hands ache.

He cracks his knuckles, asks the boys if they’re ready for a beer, remembering his first.

At fifteen he drank Rainier, bittersweet scent biting his nose while he sipped,

making him crave pancakes all night. He didn’t know why until he remembered hunting

trips when he was five and six, Brown Betty, the old flat top stove at his uncle’s cabin.

Uncle Joe would tinker the diesel flame into smothering heat, sizzle of bacon

while Jim’s dad poured Hamm’s in the pancake batter, saying, Our little secret.

Holding a burnt handled spatula, he’d flip white beer cakes mid-air.

Outside the web locker, Jim’s crew chuckles, calls it a day, each popping a beer tab.

At home their fingers twitch all night, tie imaginary hitches, sheet bends,

loop knots, a bowline on a bight. Jim dreams of the whole net flexing,

all the pearl-sized knots shrunk and snug, rippling in the current.

- Published in Series

TWO SHORT STORIES by Kevin McIlvoy

The Luthier’s mother’s mouth’s openness

The Luthier’s mother’s mouth’s openness, her hands’ finger’s

tremblings, her red hair’s fires’ warnings. It’s what you saw if you

were making your last visit to her ever. You were the Luthier’s

mother’s Possession when you walked into her son’s guitars’

home, in which son and mother also lived together in one room.

Inside their home’s heart’s sounds: the tub’s faucet’s dripping’s

splashings and the refrigerator’s coils’ hymning humming and the

clock’s hands’ frettings and the floorboards’ one warped

floorboard’s creaking. It felt like everything you heard was also

hearing everything else, that nothing resting there fully rested.

I know all this because I lived there once with an older sister

named Bender. She was the one who saw after me. Ran away.

And no word again from her. My feet drummed the dead forest, I

heard my face in the face, and from hunger I prayed inside

the box’s light. I felt my boy’s soul displace the small body of water. I

didn’t like that they had stopped that splashing sound.

I was the Luthier’s mother’s first husband’s second child by what

people called The Widow’s Previous Marriage. The only child left, I

was an extraneous adverb when my father, the verb of the family,

died. The Luthier, who is the second son, is the Luthier’s mother’s

other.

I, too, was a Luthier though not as skilled as he, The Luthier’s

Luthier. Call them “Sorrow’s sorrows,” the guitars I made. Call his

“Rapture’s Raptures.” He was my teacher. Twice his age, I was the

Luthier’s mother’s son’s favorite pupil. I was there to learn how to

finish dreadnaughts that would sell fast. Banking on his

reputation, I would claim that he made them.

Once there was one he named Elizabeth Cotton. It is bad luck to

name a bad guitar. It is good luck to name a good. He had never

made one better. “Liz,” he said, at the end, “this will not hurt.”

And he was gentle. “Liz,” he said, “you’re going to like this.”

He whispered into her soundhole, “Liz, baby, what is it?” and

listened for her answer. The Luthier and I never talked with the

affection resounding in the Luthier’s guitar’s conversations with

the Luthier. There is a love that is a reflection of love’s reflection.

There is a frame inside the form, there is a vice you use to force

the edges to bind. There is the floating or flying seed still in the

grain. The stars arisen, the kingdoms fallen, the green, the void;

you touch the tuning fork across the skin of the sky, snow, rain

still in the sound. Moonlight. Sun. Nests in the limbs, and in the

nests the hungering young. You loosen the vice, and you are done.

“You fixed the tub?” I asked. The Luthier’s mother answered for

him: “Fixed.” They had even taken the duct tape off the Hot and

Cold handles. (It broke my heart, that repair.) The Luthier said,

“Finished.”

I asked if I could take her. Together, the Luthier and I put her in

the case.

I left. She went with me everywhere I went. Forty-one years ago

today.

At dusk, as always, Bender sang to us

At dusk, as always, Bender sang to our congregation, silver hair

greasing her blouse, and silver muffling the toes of her boots.

When we were grade-school children, she and I liked duct-tape.

We liked it like you could never believe. Our favorite thing to steal

from the corner store was that silver coil. The way it ripped

across, how it stretched over. It gripped!

She stood on the white twenty-gallon empty drum, her bootheels

burning the plastic, her tempo uneven. We were a communion of

over a dozen church-bums who loved her and were frightened by

her hawk-at-the-tree-crown and hawk-on-the-glide shoulders and

head, her wings at her sides, her hands palms out, fingers curled

up.

We once duct-taped a picture of our father, who was dying in the

Simic State Penitentiary hospital, to a globe our aunt Horror sent

whose name was actually Hortense. He clung to the deep South.

He spun fast without flying off. When it slowed down, his head did

a half-turn on his neck, then a turn back by half that. We tore the

thing apart, duct-taped the entire planet, kicked it anywhere we

wanted. Dented part of Asia and most of Antarctica. Had to re-

tape.

Bender could see me. She looked at me. Hungry, we both had

listened to the God-hype you had to swallow in order to be

allowed to eat the soup at this mission. The tables were set in the

chapel that once had a God’s-eye skylight. Through a screen of

sloppy black paint, full moonlight smudged her gaunt face and

temples, her silvery upper lip and jaw.

She sang, Hey now. Hey. That’s what I feel. How about you?

We were all sick to death from eating so much God venom. This

serpent’s voice tasted good. Her drumming bowed us lower over

our bowls, our spoons witching the broth.

When she turned nine, Bender and I duct-taped her birthday cake

– the wrong flavor and no icing – taped the candles, taped our

cousin’s bicycle handles, seat, tires, chrome fenders, who said he

was forced to come to the birthday party. We attached our

stepmother Dillo’s hands to her knees because she napped curled

up drunk, which was not birthday-appropriate we felt. For her

convenience, we taped her whipping switch, which we had taped

and broken and overtaped, to her right claw.

Bender’s voice scraped her own clogged reed:

Hey now. Hey. That’s what I feel. How about you?

Of all hours, Bender should bless ours. Of all hungers she should

solve them here.

You feel it? You feel it. You feel it too.

Our congregation lightly hammered our tables in tune with her

coffin-lid-thumping boot.

Sixty-one years earlier, our mother told me nothing and no one

could save my sister, that some darkness sings only darkness.

You never ask me about me, Bender said.

O, Bender, I answered my sister-sawyer who had only survived

her own self-killings because she sang.

You never ask me about me, she said again, though she knew I

was afraid to hear her answer.

When she laughed she sounded forgiving.

Need duct tape? she asked.

I had become a musician along my way. I injured and reinjured my

guitar until we both were near dead. Kicked out of the band, I

marked it SOLD but kept it, slept with it, dreamed there was room

for me in its shell.

I did. I needed some.

- Published in Series

FWR Monthly: May 2015

Starting this spring, we’ll be sending our subscribers monthly “mini-issues,” each one edited by different members of our staff. We see these monthlies as a chance to showcase more great work, and explore more topics of interest, than we have room for in our regular biannual issues.

To kick things off, I’ve chosen work that blurs the sometimes arbitrary boundary between poetry and prose. As a reader, editor, and writer, I’m most interested in work that blends the finest elements of both — the kind of work in which one hears, as Robert Frost once called it, the “sound of sense.”

I hope you like these “poems” and “stories” just as much as I do, and will keep an eye out next month for a brand new feature, chosen by a different member of our team. Until then, thanks for reading.

~ Ryan Burden

Managing / Fiction Editor

TWO STORIES

by Kevin McIlvoy

THE LUTHIER’S MOTHER’S MOUTH’S OPENNESS

The Luthier’s mother’s mouth’s openness, her hands’ finger’s

tremblings, her red hair’s fires’ warnings. It’s what you saw if you

were making your last visit to her ever. You were the Luthier’s

mother’s Possession when you walked into her son’s guitars’

home, in which son and mother also lived together in one room.

Inside their home’s heart’s sounds: the tub’s faucet’s dripping’s

splashings and the refrigerator’s coils’ hymning humming…

TWO POEMS

by Sierra Golden

LIGHT BOAT

Jesse isn’t really a pirate, but the Coast Guard thinks so when he calls to say he found a body. It doesn’t matter that she’s still alive, so cold she stopped shivering, blue fat of her naked body waxy and blooming red patches where his hands grabbed and hauled her from the water. He stands over her with a filet knife, slowly honing the blade as he waits for Search and Rescue. The glassy eyes of a dead tuna stare up from the galley counter. At dusk, Jesse flicks on the squid lights…