FOUR POEMS by Marie Lundquist, translated from the Swedish by Malena Mörling

What do we do with what we lack? A cleft palate weakness, a harmony,

a sibling with whom to share ourselves. Quick and quarreling the rain

falls on memories no one is polishing. A few remain, hidden as if in

secrecy. New names ring over the graves, mute and soft like

moss-mouths.

*

My memory lines up the alphabet so that I can throw knives at it. Each

word carries an executioner’s hood pulled down over its past. My father

climbs up on rickety ladders and screws new light into fly-speckled

lamps. Always this care for the things. About the enlightened child.

*

To speak without friction about death, about the essence of a poem,

about the untruthful in this, by gestures’ created speech. Not to be able to

believe that you can control your life and let your hair fall everywhere. I

warm my hands on the cheek of the child glowing with sleep and carry

forth the words enveloped in mumblings’ quilt.

*

Who am I? Who are you? I lift my name up from the paper and blow on

it. With my hand I open the mountain you walked through.

Malena Mörling is the author of two books of poetry: Ocean Avenue and Astoria, and her third collection, Lumina Station, will be published in 2026 by Alice James Books. She has also published translations of work by Nobel Laureate Tomas Tranströmer and together with Jonas Ellerström, a collection of the Finland-Swedish poet Edith Södergran, On Foot I Wandered Through the Solar Systems, the collection 1933 by Philip Levine into Swedish, and they have edited and translated the anthology, The Star by My Head: Poets from Sweden published by Milkweed Editions. Mörling has received a Lannan Literary Fellowship, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Dianna L. Bennett Fellowship from the Beverly Rogers, Carol C. Harter Black Mountain Institute. (Photo Credit: Samuel J. Brady)

Malena Mörling is the author of two books of poetry: Ocean Avenue and Astoria, and her third collection, Lumina Station, will be published in 2026 by Alice James Books. She has also published translations of work by Nobel Laureate Tomas Tranströmer and together with Jonas Ellerström, a collection of the Finland-Swedish poet Edith Södergran, On Foot I Wandered Through the Solar Systems, the collection 1933 by Philip Levine into Swedish, and they have edited and translated the anthology, The Star by My Head: Poets from Sweden published by Milkweed Editions. Mörling has received a Lannan Literary Fellowship, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Dianna L. Bennett Fellowship from the Beverly Rogers, Carol C. Harter Black Mountain Institute. (Photo Credit: Samuel J. Brady)

- Published in Issue 34, Poetry, Translation

THE HEART OF A SIREN by Margo Rejmer, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

From the recent collection The Burden of Skin.

The sea was groaning like a wounded beast. Is the sea hungry? Or thirsty? Is it afraid?

Dawn was slipping through holes in the thin curtains. Lying in bed, Enriko began to make out the contours of objects. He listened to the sea. It was calling him as usual, but this time it was full of pain; its sobs were breaking through the roar of the waves and then falling silent on the shoreline. The sea was lamenting – it had called something to mind and was yearning for it. It had seen something and wanted to tell him about it. What a great burden to bear: the capacity to see and remember everything, to be there forever.

Enriko got up and approached the window quietly, careful not to wake his grandmother, and put an eye to a hole in the curtain. Light interlaced with gold. Violet streaks of cloud. And over there in the distance, the steadily breathing body of the sea in infinite motion, arranging itself in stripes of indigo and gold. Enriko touched the cut on the back of his hand and began to suck it, in case something was still seeping from the wound. A chasm of a wound. A scab was slowly forming. Grandma had examined it last night and said it was nothing serious, but the tissue had come apart and there’d be a scar. Maybe on his arm too.

“Men have scars,” she said. “You’ll have more scars in the future. And you’ll be proud of them.”

He gazed at her calm face, sunken cheeks and small, sharp nose. His grandma, composed of nothing but creases and silence, clothed in a layer of widow’s black that would be her skin to the day she died. She smiled to herself as she washed his wound, and swung her head. She smiled the same way when Enriko’s father screamed at her, she was unmoved, as if mentally far away, recalling something not too pleasant, but essentially insignificant. Grandma had scars too, two parallel lines on her forehead, one higher, one lower, and a dimple on her chin, as if cut by a knife. Once when he asked her where they came from, she said life carves marks on people. The crown of her drooping head shone silver, shot through with streaks of dark hair. Both were reflected in the mirror above the table: she was huddled, gone grey, like a mushroom and as patient as a mushroom spawn. Enriko was slender, prematurely stretched like a sunflower, with narrow shoulders and extremely long hands, curly hair that grew so fast his father cut it for him every three months, always brutally, as if he couldn’t restrain his anger at the hair for being so thick and growing as furiously as weeds after rain.

“Curls,” his father kept saying, stumbling on that word and muttering it like a curse. “Curls,” he’d hiss, waving the heavy, rusting tailor’s shears he’d taken from Grandma’s basket. “I’ll cut off your curls, you inhuman creature.”

Grandma sometimes complained that such beautiful hair was wasted on a boy, a girl would have had more use for it.

“You don’t look like anyone, but you do have your mother’s hair,” she once told him. “Though even hers wasn’t quite the same – your hair is bursting with life. Your mother’s dragged her to the bottom.”

He peeped through the hole in the curtain again, his long eyelashes splaying against the fabric. The sea was glittering in the distance like a golden bracelet. It was a soft, subtle morning. Yesterday his father’s belt buckle had slashed Enriko’s body like a knife. His father had beaten him and then left. When he came back he wouldn’t even remember why he did it. He’d look vigilantly in every corner, seeking a new excuse, strong as a bear, with one heavy leg that he dragged behind him, as if it didn’t belong to him. Hobbling. Clatter. At these moments Enriko’s senses were so highly sharpened that he could have read his father’s thoughts, but there weren’t any thoughts in his father’s head, just a swarm of wasps stinging from the inside. The sea glistens. His father is a wine-skin full of foul, murky water. Any moment now this water will come pouring out of him. He’ll try to drown Enriko in it. But Enriko can’t be drowned. If needs be, he’ll change into air. He’ll change into sea foam. With his eyes closed he’ll follow the movement of his father’s eyeballs. His father will strike the first blow, unaware that he’s hitting the crust of a shell, an empty void. Because Enriko will be there already, on the other side. His hair will spread out on the surface of the water. Like black seaweed swaying. The child who emerged from amniotic fluid will return to the water.

He carefully pushed the window frame, raising it a touch without making a sound. Grandma was sleeping on a narrow sofa bed against the wall, on the other side of the room, immobile, with her hands crossed on her chest, as if trying not to take up too much space. If she woke, she’d start her grumbling, as gentle as the ticking of a clock, but endless. Why are you always trailing about by the water? The sea brings nothing but trouble.

Sometimes Enriko fantasized that one day a great storm would arise and the water would pour in all the way to the threshold, seize Enriko and carry him far away, to his mother.

He could feel the faint chill of the flooring under his feet. He slid back the window and ran ahead, and kept running, while his feet exchanged greetings with the stones and sand, feeling their dampness and roughness.

The sea lit up at the sight of him. The pain eased, the first rays of the sun twinkled on the waves. As nobody had ever asked him about it, he’d never told anyone why he plunged into the water every day. He just did. There, the sea came pouring inside, under the cover of his skin too. He loved the sea and he thought like the sea. His interior was the sea, the skin layer just a border separating the sea from the rest of the world. As he lay in bed, he was lulled to sleep by the rocking of waves that flowed through his body, crashing against the shore of his skin.

As every morning, he sang his song to the sea. And it replied with its roar and rocking. As he entered the foam, the waves embraced him. The water began to hiss, washing over the stripes on his hands and forearms, stinging his skin, but Enriko felt gratitude, knowing that salt cleanses wounds. From afar he could see his house, an inconspicuous yellow block with a flat roof, white sliding windows and plastic shutters. He had nothing in common with this house. Here, in the water, was his home. With his eyes closed he could feel rings of it shimmering around him. The sun’s rays danced on the surface of his eyelids.

Stretched out on his back, he continued to drift until the sea said that’s enough and carried him onto the shore.

Now he was on the alert. With back bent, head bowed and nose close to the sand he trotted along, looking to either side. He had changed into a dog. He was tracking. The air was sharp, leaving specks of salt inside his nostrils. The sand smelled of moisture, snail skin and the dried-out bodies of jellyfish. There was no day when he didn’t find something. Long ribbons of seaweed which he braided into plaits, very like the ones the sirens wore. Shells saturated with gold, mother-of-pearl and aquamarine – the valuables offered him by the sea because it loved him. Lots of little gifts. Enriko didn’t need as many, but the sea was loving and generous, and adored pampering him. What he liked best was when it presented him with toys. Sweet wrappers covered in words he didn’t know. Small objects, sometimes of no use, like a flip-flop or part of a plastic deckchair. Enriko couldn’t accept all the gifts, and simply left most of them on the beach. But sometimes there were real treasures: a Smurf figurine, a fluorescent toy spade or a rubber seal pup. Enriko gazed lovingly at the seal pup, and then threw himself into the waves to thank the sea, and floated on his back, with his head submerged and just his nose protruding above the surface. The sea whispered in Enriko’s ear that he deserved everything that was most beautiful, it whispered to him that he was good.

That day Enriko found as many as two gifts on the beach: a piece of glass polished by the water, as lovely as an emerald, and a seashell almost as big as his hand, with thick walls covered in convex stripes. He turned it over in his palm on all sides, drew the tip of his finger over the bulging bands, unable to believe how heavy it was. The sapphire streaks passed into azure, which faded to change into bleached orange, bordering the edges of the shell. It sang the song of the sea into his ear. He felt sure at once that his uncle would like it. His uncle would be so delighted when he saw it that he’d start to draw immediately.

Enriko jumped up and raced ahead, almost unaware of the resistance the sand was offering him. He had changed into the wind. He ran diagonally across the beach, raising clouds of sand around him, until he felt the stab of pine needles on the soles of his feet. Briefly he wondered whether to go home for his shoes, but that meant the risk of encountering his father. It was never entirely clear what business took his father to the city, when he’d be back and what mood he’d be in. Enriko cut across a small wood that separated the beach from the village, and ran on over compacted earth, still damp from the night, full of potholes and ruts, down which on rare occasion the tired, battered cars of residents wobbled their way. On one side stretched an olive orchard that fell away steeply towards a meadow bordering the beach. On the other side rose some ugly bungalows, built here out of longing for peace and safety, but without further thought, painted in garish, self-satisfied colours designed to distract attention from their hideousness. The houses carried large water collectors on their flat roofs, because no authority had ever had the know-how, desire and courage to extend a water system to the village.

“They can’t imagine what their life would be like if they kicked up a fuss, so why on earth should they?” his uncle would say angrily.

They were so alike, Taso and Ana, his uncle and his mother. Twins. So the photos told Enriko. Only a tiny difference in the size of their noses, the width of their faces and the length of their chins betrayed that they were of different sexes, but the set of the eyes, the shape of the lips, and the hair were just the same. Taso had left their mother’s womb first, so in time he had adopted the title of older brother. He had always done his best to protect his sister, and he’d done it well, until he left for Greece, and Ana got married. Looking through his parents’ wedding photos, Enriko sought a trace of his uncle in vain. Taso hadn’t even come when his nephew was born. Only when he learned that Ana had disappeared did he come back. He went round asking questions, paid bribes, and had a fight with someone to a point of bloodshed. Yet the village said nothing. Finally he had founded “Ana’s Bar” to remind everyone that Ana was missing. To disturb their peace. One day someone will come into the bar who who’ll tell me the truth, he kept repeating. In vino veritas, you sons of bitches. That was what he said when he was sober, and also when he was drunk.

Seven years had passed. In this time people had brought him rumours and gossip. They laid accusations on the counter. They drank on credit, promising to bring in eye-witnesses. They lowered their voices whenever they spoke of the culprit. They cursed the policeman and all the police in the country. Those who did business with the police cursed the most.

At eight a.m. the bar was still closed, but Konstantin was already sitting at the counter, Taso’s best friend, who came to the bar early in the morning and was the last to leave. On a good day, he played the accordion, he played acutely and with feeling; Taso would rest his hands on Konstantin’s shoulders and sing, just as if sirens longing for the sea were circulating in his blood stream.

Konstantin patted the chair next to him and moved his plate of white cheese, bread and honey towards Enriko.

“Hey, kid, have you been swimming since daybreak?” he asked.

Enriko nodded and beamed.

“What did you catch?” asked Taso.

Enriko pulled the blue-and-orange shell from his pocket with a beseeching look on his face, and Taso smiled.

“Beautiful. We’ll do a drawing,” he said.

“It’s three months since it last rained,” said Konstantin with a sigh. “People are saying that where the river falls into the sea, on a level with Tanis, you can see the roof of an old ship that used to transport timber. Something for you, Enriko.”

Enriko nodded. Just then Adego and Klodi arrived for morning coffee and news, and when Celestino came in, the bar, which had seemed empty, suddenly became too small. Celestino, nicknamed Concertina, was small and stout, with narrow shoulders, a belly like a ball and a slight squint, and regarded himself as a gigolo. His wife had died young, of heart disease, before she’d had the chance to have a child. He said it was so long ago that sometimes he had to look at her photo to remember her face, and that if he wanted, he could sleep with any woman in town, but he was bothered by diabetes and sweated terribly – and no girl was worth moving from the village across those potholes for. When you’re on your own you can save lots of money and energy, and spend them on all sorts of interesting occupations, such as eating and drinking with your friends.

“That Karaj girl is part snake, part wild cat,” said Celestino to open the conversation. “She came to join her parents from Italy and keeps walking past my house to show how her nipples jump out of her low-cut dress. Konstantin, play something on your accordion at the front door, maybe you can lure her in here.”

Enriko sat against the wall, and on a table covered with a cloth full of holes he lined up the shells he’d brought to his uncle’s bar and kept in a basket near the fireplace. First he organized them from smallest to largest, then according to shape, from the roundest to the most conical, then by colour, from the darkest to the lightest. And over again. He’d listen to the voices and wait for Konstantin to play his accordion, though Konstantin only played in the evenings, and only once his pals had stood him enough drinks.

At twelve Agron checked in, because he always took his heart medicine at noon, and he was sure it should be washed down with walnut rakija, or it wouldn’t work. After drinking it he’d be pensive and stand leaning against the counter, picking his nose with the long, horny nail of his little finger.

“Unlike you lot,” he said, “I respect my health and I hope I’ll be drinking rakija at all your funerals.”

Enriko thought the old man was coming up to eighty, but Taso said he was only a few years short of a hundred. Agron walked exaggeratedly upright, like a soldier, and always wore the same shabby grey trousers pulled high above his belly and held there by a belt. Sometimes Enriko saw the old man from afar, plunging himself into the sea at dawn, but Agron never called him over to join him. Just once Enriko had asked him why he had that long, claw-like fingernail, and without blinking the old man had replied that he pierced lizard hearts with it. From then on Enriko had never approached him again.

In any case, the men at the bar usually ignored him too, only Celestino would say with a laugh, as he drank up: “One day you’ll grow up to be a beautiful girl, Enriko!”

After twelve the bar emptied, so Taso and Konstantin settled on the veranda, smoking cigarettes. Enriko squatted on the steps. He was waiting for the mouse that lived under them to emerge, or for some other little creature to appear for a drink of water from the bowls set out on the floor.

In the distance a man walked past who had stopped dropping in at the bar ever since it became known that he helped his wife to wash the dishes. Celestino had caught him red-handed one day when he knocked at his door with the news that a car with foreign plates had run over his hen.

“What I saw was beyond human comprehension,” Celestino had said in a loud voice as he told the story at the bar. “Mr Dishcloth was standing by a bowl of water, rinsing plates in it! The only thing he was missing was an apron or a skirt.”

Afterwards the wretched man explained that his wife’s fingers were twisted by rheumatism and whenever she washed the plates she broke them; their children had gone far away and there was no one to help at home.

“But he could spout whatever nonsense he liked – the shit has stuck to him anyway,” Celestino concluded. They’d all started calling the old man Mr Dishcloth, and only Celestino called him Carpet Slipper, because he reckoned Mr Dishcloth was too high a compliment for him.

“Who knows,” wondered Celestino, “perhaps there are more like him in the village, but they’re better at hiding it.”

But his pals assured him there was only one Mr Dishcloth.

Enriko raised a hand to greet Mr Dishcloth, who nodded to him from afar, and in Taso’s direction too. Nearby a cat ran past, which showed up at the bar now and then and ate everything they gave it, even bread and potatoes. Enriko had sometimes seen the cat flash by with a lizard or a robin in its mouth. Once Enriko had blocked its path to save the creature, but he soon found out it was impossible to force the cat to give up its prey, even if he tried to distract it with a piece of meat. Another time he and Taso had stopped the cat with a live, struggling sparrow in its mouth, and had poured a bowl of water on its head, but the cat hadn’t even twitched; they’d heard the crunch of fragile bird bones snapping under the pressure of its jaws. The cat stared at them, its eyes shining, because it could feel that sound throughout its body and knew it had got its way. What could they do? They let it go, and Enriko went on offering it yogurt, bits of chicken and bread, hoping to save at least one creature by doing so.

In the distance the village policeman rode by on a ramshackle bicycle without looking in their direction. He had only shown up at the bar once, but Taso had approached him and said something into his ear, after which the man had never come back again.

Enriko took a pencil, a sheet of paper and a shell and placed them before Taso. His uncle glanced at the boy’s hand, at the closing wound, and then looked him in the eye.

“Men have scars,” muttered Enriko.

“Everyone has scars,” said Taso. “But it’s better not to have them.”

Enriko thought his uncle’s hand was shaking as, suspended just above the paper, he drew an outline in the air that would appear seconds later on the paper in the shape of a shell. His long, curly hair cast dancing shadows on the page. Right now, Enriko was thinking, his uncle looked like his mama. The good mama from the photos, whom no one was willing to tell him about. Mama Ana, whom he couldn’t remember. Mama, who had vanished two years after he was born, because she’d changed into a siren.

“Does he often hit you?” asked Taso, looking up from the drawing.

Enriko nodded to say neither yes or no. How many times was often? Every day? No. Sometimes it was enough for Enriko to wobble after the first blow and tumble to the floor, and then his father would stop and walk away, as if he’d remembered other, more urgent matters. Grandma said that essentially his father had a good heart, but Enriko thought his father was lazy. He easily lost interest in beating the child. He didn’t want to lean down to hit him; by and large he rarely kicked him – he preferred to use his hand, his belt or a stick. Looking him in the face. As equal to equal, although they weren’t equal. Grandma would tell his father to stop, or he’d kill the child, and his father would reply that the child could take it. The child had to be as strong as he was. One day he’d be doing the beating. He had to know how. He had to feel it on his own skin. He had to toughen up. A man should be resilient. He’d run into worse things than that in life. And he mustn’t whine. It was all basically to teach him not to cry.

“It’s raining, drip, drip, drop,” hummed Taso and drew Enriko towards him. He rocked in his uncle’s arms just as he did in the water. How many tears had the sea shed to be so salty?

He wiped his face, kissed his uncle on the temple, though he never did that, put a heavy, round shell into his shorts pocket, did up the zip carefully and ran towards the river. From quite far off he could already see the dull, rusty top of the boat sticking out of the water. Nearby the river fell into the sea and the current was strong, but Enriko wasn’t afraid. The water could carry him but never drown him. He took off his shirt and jumped in. The sea is mighty. It can kill anyone if it wants to. His father too could kill anyone if he wanted. But the sea is good to Enriko, the sea embraces him, the sea loves him. And his father wouldn’t want to kill him either. He always knows when to stop hitting. Sometimes Enriko thinks one more blow and he’ll die. The life will fly out of him along with his breath. At these moments he changes into the sea, his consciousness rocks like the waves. But his father knows when to stop. How not to take his life. How to leave some of him for later. Enriko belongs to his father and his family – so it always has been, and so it always will be.

He swam up to the boat and dived. The metal hulk was like a rusty whale. He swam the length of the hull underwater, brushing his fingers against its rough edges. Clinging to its corroded surface were plenty of mussels, sea snails and sea anemones – these interested him the most. Softness hidden inside speckled, calcareous armour. The bumpy texture of rust-eaten metal under his fingers. Trembling dark purple protuberances and long black spines. A vast light overhead, a vast depth underfoot. Boundless water. Boundless time.

When Enriko finally surfaces, in the light of the golden hour his body shines like copper. Just ahead of him rise the honey-coloured walls of sand dunes, shot through with darker streaks of earth, as if someone has laid out graphite ribbons on a quilt of gold. In the distance Enriko can see two small figures on a cliff top, holding a long bundle in their outstretched hands. He blinks. Without much thought, he swims towards the figures: one of them shouts something to the other, until finally it raises both hands, causing the object it’s holding to knock against the ground. Then the second figure drops the burden at its end too. Enriko can see a tall, burly man hobbling in the opposite direction, but after a while he turns around. Once again he shouts something to the person standing opposite him. Enriko swims fast, and the matchstick figures grow before him, gaining details, though both men have their heads hidden under hoods. Once again they grab the bundle they were holding, and with a swing they throw it into the water. For the moment the sun’s rays dazzle Enriko, but now he’s shot through by certainty – the thing the men are throwing into the water was once a human being; a cobweb of long, female hair spreads in the air, the shape falls like a stone, and then there’s a deafening splash of water in the silence, as if a bomb has exploded right in front of him.

He dives. To forget what he has seen. To see with his own eyes. But he can’t see anything beyond the dark, transparent depths. When he surfaces, there’s no one on the cliff top. He swims towards the spot where the body was thrown into the water, but the surface is instantly smoothing over, as if the sea has swallowed the body, as if the body belonged to it. He dives again and again, violently catching mouthfuls of air and going deep underwater. He looks around in all directions, but can’t see a thing. No trace of the body, no trace of the hair. Just flashing shoals of fish and ribbons of seaweed glittering in the water.

He comes up to the surface. The sun’s rays have taken on the colours of fire, the shadows have grown longer. Again he goes underwater, sinking ever lower, immobile, into the darkness and silence of the deep.

And all of a sudden he hears singing, at first distant, like the wailing of the wind, and then his body is pierced by a sound that stuns and terrifies him.

He swims to the shore. He walks along the beach, across the sand, which turns into old gold beneath his feet. The shell in his pocket is weighing him down like a boulder. He walks at a steady pace, as if in a trance, though he has no idea what he has just seen, where he’s going or what he’s about to do.

His legs carry him towards home, and as soon as he can see the modest yellow block in the distance, a shiver transfixes him, because the house in which he has spent his whole life seems alien, as if he didn’t belong to this place or to this world anymore.

Through the open door he enters the house and sees his father, an immobile figure sitting on the couch, absent to a point of lifelessness.

He takes the shell from his pocket and clenches his palm around it. He can feel its weight under his fingers and the hardness of its walls. He only has to go up and strike his father on the one spot on his temple where the skull is fragile. Strike, and then batter his head with a steady motion, again and again, endlessly, just as his father’s blows seemed never ending as Enriko watched him lose his breath from the perspective of the floor.

He only has to throw the shell at his father for the man to leap up like a rabid beast and start to kick Enriko blindly, until he has lost reason, until the life has trickled out of the boy along with his blood.

He looks at the steel blue of his father’s eye, in which there’s no trace of the sea, no touch of longing for the sea.

“Go away,” says his father. “What do you want? I’m too tired to beat you.”

Enriko puts the shell to his ear and hears a whisper. She’s calling him. He drops the shell and runs out into the yard, then races across the sand, which in the light of the setting sun is like coral dust.

He enters the water. The pain changes into the foam of the waves that are washing against the beach, leaving shining stripes on the sand.

But what if the sun never sets? What if it goes on hanging like a red ball over the horizon forever? He, the sea and the sun will freeze and change into a picture. Enriko will dissolve in the sea. He’ll become the sea.

He only has to swim ahead, endlessly.

His heart is beating to a completely new rhythm now, to the rhythm of ebb and flow. With the tip of his thumb he touches the membrane between his fingers. He can feel his body lengthening and growing slender, his legs joining together to form a tail, and instantly his skin is covered in thick, heavy scales. The time has come. Somewhere in the distance, beyond the horizon, he can hear singing.

Antonia Lloyd-Jones has translated works by many of Poland’s leading contemporary novelists and reportage authors, as well as classics, biographies, essays, crime fiction, poetry and children’s books. Her translation of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by 2018 Nobel Prize laureate Olga Tokarczuk was shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International prize. For ten years she was a mentor for the Emerging Translators’ Mentorship Programme, and is a former co-chair of the UK Translators Association. Her recent publications include a translation of My Name is Stramer by Mikołaj Łoziński, and as compiler and co-translator, The Penguin Book of Polish Short Stories. (Photo credit: Mikołaj Starzyński.)

- Published in Fiction, Issue 34, Translation

THREE POEMS by Bejan Matur, translated from the Turkish by Nell Wright

No spring

The Judas-trees have bloomed

we’re mourning again

no spring

no country

and blood everywhere.

When kissing the earth

They talked about a cavalry girl

walking. Tenacity

crossing valleys, mountains.

Saying as she goes,

how much I believed

how bound I was.

Foremost when climbing

mountains and valleys,

kissing the earth with a breath

no one knows.

As if the mountains were beginning for the first time.

The valleys for the first time traversed.

The mountains remained far away from us

My mother asks about that shifting memory

did we offend the mountains she says.

Are the mountains angry with us?

I love the flowers my mother says.

If I die

gather wildflowers, place them

on my chest.

Speaking this way my mother says suddenly

is the world a lie or the person.

My father driving the car straight toward the mountains

not looking back

says the person is the lie.

The person’s the lie.

Just like the weight of those cradles

just like the glazed beauty of that acorn

the person is the lie.

Each thing appears to us, is lost

the wind brushes us and withdraws.

And like wounds healed by writing, the world

one day heals.

Oh those who don’t heal

their milk smell,

the mother regarding her blue veins feels

grief

the mother regarding the mountains sighs,

the birth.

We move along the road

my mother my father

and desolation

we move toward the mountains that aren’t ours.

And at a crossroads our souls entangle

a moment between past and future

we wait

as though only that moment exists

always that moment.

Father’s indecision

Mother’s silence my

confusion

the past and future were taken from us

we look at the mountains

there is no consolation

and there will be none…

Nell Wright is a writer, translator, and visual artist whose work has appeared in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, Poem-a-Day, and elsewhere. (Photo credit: Benjamin Krusling)

- Published in Issue 34, Poetry, Translation

URGENT: NEWS OF THE DEATH OF HIBA ABU NADA by João Melo, trans. G. Holleran

Excuse my urgency, oh right-thinking beings

especially you translucent

and self-referential poets,

but one of our sisters,

the Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada,

has just died in Gaza under the shrapnel of a benevolent bomb,

sent by another God,

different from the one she spoke with

every day.

I hesitated to convey this fateful news

so hastily. Perhaps I should wait

for the leaden grey smoke from the bomb that killed her to dissipate,

while she, surely,

scrutinized the sky for a sliver of light and

maybe even

the last birds.

Or, more convenient yet

it’d be better to say nothing,

until today’s hegemonic oracles,

like all oracles,

circulate an official statement

denying it as usual

without any doubts

or uncomfortable questions.

But when I read

the last words of Hiba Abu Nada before she died,

I was moved to spread this news,

before her banner could be censored

by those who defend selective liberty:

“If we die, know that we are content and steadfast,

and convey on our behalf that we are people of truth!”

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

Grace Holleran translates literature from Portuguese to English. A PhD candidate in Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies & Theory at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Grace holds a Distinguished Doctoral Fellowship with the Center for Portuguese Studies & Culture and Tagus Press. Grace’s research, which has been supported by a FLAD Portuguese Archives Grant, deals with translation and activism in the early Portuguese lesbian press. An editor of Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism & Translation, Grace’s translations of Brazilian, Portuguese, and Angolan authors have been published in Brittle Paper, Gávea-Brown, The Shoutflower, and others.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Poetry, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Olivia Elias, trans. Jérémy Victor Robert

Day 21, Words Are Too Poor, October 28, 2023

words are too poor but I have only them

my only wealth

empty my hands & so great the sufferings

here again I press my arms around my chest

here again I get into this old habit of covering the page with little

squares filled with black ink

the little squares of our erasure

/

I write what I see said Etel Adnan* who knew a lot about

mountains’ strength as well as Catastrophe

I also know the power of this Mount facing the sea

Carmel of my very early days Mount Fuji of absence

& denial around which I gravitate above it the

black crows of desolation

as I know all about our Apocalypse which keeps on repeating

repeating the earth turning on its axis the sun that veils its face

/

here’s what I see

the madness of the overarmed Occupying State

crushing bodies & souls live on screens at least until

night falls a night of the end of the world only

pierced by ballistic flashes

in Sabra & Shatila the spotlights

. illuminated the massacre’s scene

today in this Mediterranean Strip of sand

. total darkness shields Horror

the sky explodes in a thousand pieces amongst

monstrous mushrooms of black smoke the time to

count one two three towers collapse one

after the other like bowling pins their inhabitants

inside then get into action the steel monsters

flattening the landscape they call it

(translation: converting this ghetto sealed off on all sides

into a 21st-century Ground Zero)

everyone wondering When will my time come?

& parents writing their children’s name on their small wrists

for identification (just in case)

/

no water no food no fuel & electricity & no medicine

decided the Annexationist Government’s Chief

let’s finish this once & for all & forever they shout

relying on the unconditional support of

their powerful Allies the ones primarily responsible

for our fate by writing it off on the bloody chessboard

of their best interests

as if their contribution to our erasure redeemed their crimes

Hear Ye Hear Ye

proclaims America’s great Chief, waving his veto-rattle

Absolute safety for the Conquerors

Hear Ye Hear Ye

chorus the mighty Allies

/

Gaza / 400 square kilometers/not a single safe place /2.3 million people /half of them children / hungry /thirsty/injured /desperately searching for missing family members dying under the rubble

& Death the big winner

/

they should know that souls cannot

be imprisoned no matter how tight the rope

around the neck & how strong

the acid rains & firestorms

One day, however, one day will come the color of orange/

/a day like a bird on the highest branch**

where we will sit

in the place left empty

in our name

in the great human House

————

*Etel Adnan, “I write what I see,” in Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito: Post-Apollo Press, 1986; Brooklyn: Litmus Press, 2021).

**“One Day, However, One Day,” from Louis Aragon’s homage in Le Fou d’Elsa (1963) to Federico García Lorca, who was murdered, in August 1936, by Franco’s militias.

DAY 74, THERE WILL ALWAYS BE POETS, December 20, 2023

instability a general rule

it seems a new ocean’s on the verge

of emerging in

Africa

& floating between

here

&

there

could affect not only people or land

but also the seasons I experienced it

of fall I didn’t see a single thing

this year the acacia’s

color even changed without

my noticing

one morning looking through

the window I realized

it was there

naked

at its feet a carpet of yellow

leaves littered the ground

nothing to keep it warm

exposed

to the cold icy rain missiles

& here I was & still I am

glued to the screen

startled by every explosion

of the red-little-ball

clinging to the glittering

garlands

as soon as one of the

flesh-eating-red-balls hits

the ground a sheaf of fire

bursts followed

by a huge black smoke

cloud

then

screams

cries

panic

agony

day & night (even

more so at night) keeps on

going the hypnotic

ballet

today

Day 74

74 days of this

will spring come back

or only a long winter

of ignominy cold hunger

history will remember

there will always be poets

to tell the martyrdom

of the Ghetto People

NOTE: An earlier version of this translation appeared on 128 Lit website, December 28, 2023.

HEAR YE, HEAR YE!

At regular intervals shaking his rattle carved with the word veto the Grand Chief of America takes the floor for an urbi et orbi statement

With the utmost firmness

broadcast on a loop

in newspapers on screens

around the world

withwithwithwithwithwithwith

thethethethethethethe

utmostutmostutmostutmostutmost

utmostutmost

FIR/MNESS

like

FER/OCITY

growing

exponentially

utmostutmostutmostutmosT

exceptionallyFirm

FIR/MNESS

FIRE/MESS

Iron balls blazing

in the sky

black & read whirls

it’s raining

black ashes

east bank not west

with the utmost

firmness

We support the Conquerors’

Right to Security

COLIN POWELL. GUERNICA. SCULPTURE

1

The devil is in the detail. Colin Powell–former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of State to the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush, between 2001 and 2005–was said to have placed great importance on this. Unfortunately for him and the legacy he leaves to history, he broke that rule on one memorable occasion

It was on February 5, 2003, when he called for a military crusade against Iraq on the podium of the United Nations, based on false evidence of weapons of mass destruction. His effort resulted in the very thing it was supposed to prevent–the deaths of hundreds/hundreds of thousands of Iraqis–& plunged the country into widespread chaos, which is still unfolding today

That day, UN officials covered with a blue veil a tapestry hanging at the entrance of the Security Council representing Guernica, the monumental work painted by Picasso at the request of the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War. Twenty-seven square meters commemorating the stormy & total destruction of the small town of the same name by the German & Italian air force, on April 26, 1937

2

In March 2021, the tapestry was returned to the Rockefeller family who had loaned it for 35 years & wanted it back. Has it been replaced? With what work? I don’t know, but I’ve got an idea. Let’s offer a cubist sculpture/assemblage of 550 stones extracted from our lands on which Settlers, protected by militias/soldiers & courts, are having a great time

Upon each of these stones

that capture the light so

beautifully

is an inscription: the name of

a village

from yesterday and today

that was

razed/ablaze

May a blue veil cover it when the Guardians of the ghetto & the bantustans take the floor

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

JÉRÉMY VICTOR ROBERT is a translator between English and French who works and lives in his native Réunion Island. He published French translations of Sarah Riggs’s Murmurations (APIC, 2021, with Marie Borel), Donna Stonecipher’s Model City (joca seria, 2020), and Etel Adnan’s Sea & Fog (L’Attente, 2015). He recently translated Bhion Achimba’s poem, “a sonnet: a slaughter field,” which was published on Poezibao’s website, and Michael Palmer’s Little Elegies for Sister Satan, excerpts of which were posted online by Revue Catastrophes. Together with Sarah Riggs, he translated Olivia Elias’ Your Name, Palestine (World Poetry Books, 2023).

- Published in Poetry, Translation

JUNE MONTHLY: In Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Nearly a year after the October 7 Hamas terrorist attack and Israel’s subsequent escalation of a decades-long project of state-sponsored genocide of the Palestinian people, Gaza continues to face deadly bombings and attacks from Israel. According to Gaza’s Health Ministry, the death toll of Palestinians is in the tens of thousands, with no sign of Israel relenting.

In response to the death and destruction in Palestine, Barricade and Four Way Review joined together to raise the voices of Palestinian poets and others from around the world standing in solidarity with them. While we stand fervently against Anti-Semitism, we also resist its false equation to anti-Zionism; we equally condemn Islamophobia, anti-Arab racism and xenophobia, and imperialism, all of which function together to murder and oppress the poor and working classes and to legitimize expropriation and forced displacement.

The poems you will read here have been previously published in Barricade and represent a desire to use our platforms to uplift and disseminate translations from and in solidarity with Palestinians. Barricade shares contributions on its forum Ramparts, a makeshift oppositional online space founded on the basis of urgency and necessity; Four Way Review has compiled a selection of Ramparts posts here, with the aim of expanding the reach of these writings and giving them a more permanent home.

Four Poems, Olivia Elias (trans. Jérémy Victor Robert)

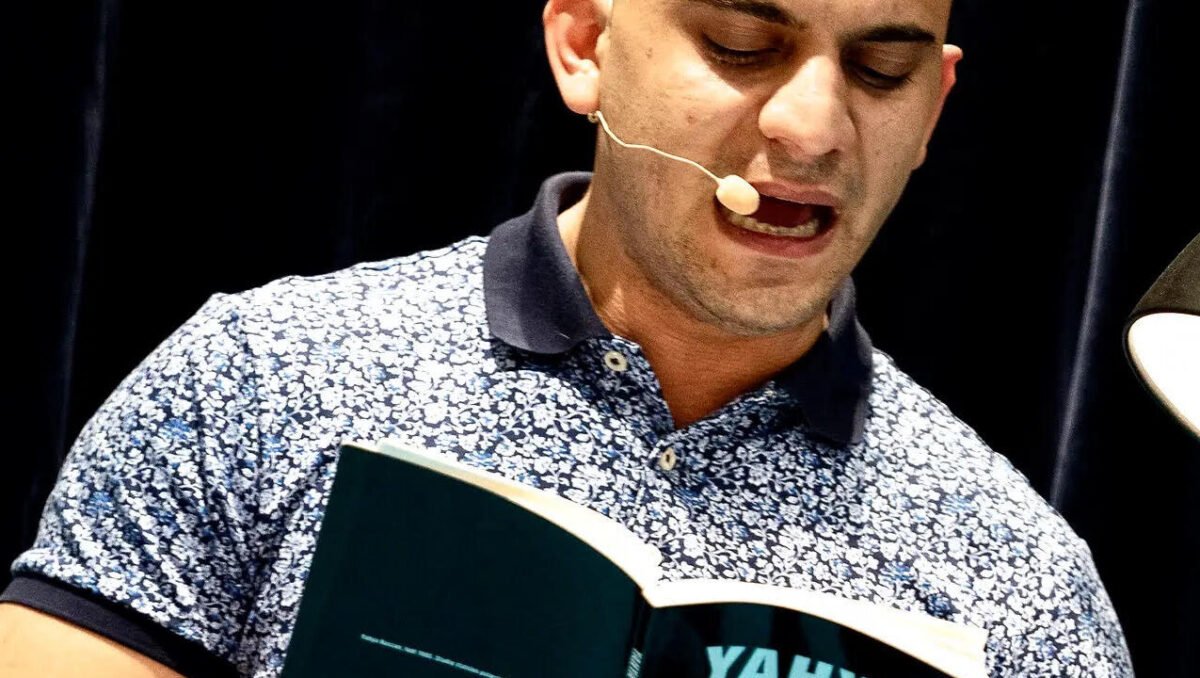

SLUMROYAL, Yahya Hassan (trans. Jordan Barger)

Urgent: News of the Death of Hiba Abu Nada, João Melo (trans. G. Holleran)

- Published in Monthly, Poetry, Translation

ECOPOETRY FROM JAPAN with Ryoichi Wago and Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FOUR POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

by Judy Halebksy

Ayako Takahashi

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FIVE POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

This folio shares recent translations from two Japanese poets, Kora Rumiko (1932-2021) and Wago Ryoichi (1968-). Kora’s poems are from the second half and 20th century, and Wago’s were written following the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown that devastated his home region. Writing in different times and from different perspectives, these poets overlap in that their writing draws attention to environmental degradation and inequality while simultaneously voicing a strong sense of place.

Kora was born and raised in Tokyo. Her childhood was shaped by the Second World War and the devastation of the Tokyo fire bombings that she witnessed as a thirteen-year-old. In the changes of the post-war era and the rapid industrialization of the 1970s, her neighborhood grew from a small community to a bustling urban area. Her writing speaks against capitalism and colonialism. At a time when many Japanese writers were influenced by European literary forms, Kora looked toward writers from Asia and Africa, all while drawing inspiration from mythology, envisioning matriarchy, and speaking to the harms and costs of nuclear weapons and nuclear power.

These themes are evident in her poem, A Mother Speaks, which is set within the Noh play A Killing Stone (Sesshôseki). Noh is a somber, serious theatre tradition that has been in living practice for more than six hundred years. Plays often have themes of connecting the dead with the living and of vanquishing evil spirits. A Killing Stone references the legend of the fox spirit and Lady Tamamo’s attempt to use her supernatural power to kill the emperor. As the story goes, her plans fails and her spirit is relegated to a stone that kills any living thing that passes over it. Kora’s poem envisions Tamamo’s power, fertility, and the potential of transformation, offering an embodied, feminist perspective on the Noh play and the legend more broadly.

Wago is a high school teacher and has lived in Fukushima prefecture his whole life. In March 2011, when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear powerplant failed, he did not evacuate, but sheltered in place in his apartment in Fukushima City, 50 miles away from the powerplant. He started a Twitter feed of thoughts and observations, which soon had thousands of followers. Pebbles of Poetry 1, from Macrh 16, 2011, marks the very beginning of his posts and the moment when people were just becoming aware of the radiation leaks. On several occasions, Wago visited areas inside the evacuation zone, a 12-mile radius of the power plant. He wore a protective suit and a radiation monitor. His poem Screening Time was written after one of those visits. Wago’s writing addresses environmental degradation with an ecopoetics that not only explores the human toll of this catastrophe, but also includes the perspectives of cows abandoned in the fields; the fruits and crops left to waste; the once vibrant towns that now stand empty; and the soil, the ocean, and the air.

January 7, 2021, is one of a series of poems that Wago wrote marking ten years since the nuclear meltdown. It voices a more composed perspective on the memories and experiences of his earlier writings. It opens with a description of flying above the evacuation zone and includes a conversation with a dairy farmer forced to evacuate the area and abandon his herd. The poem integrates quotes from Wago’s twitter feed on March 22, 2011 in the first days following the meltdown; contextualizing, in this way, the original posts, integrating them with images and details to create an immersive sense of presence. Much of Wago’s work is dedicated to restoring Fukushima prefecture, not just in terms of environmental restoration, but also of the culture and lifestyle of the region and the well-being of future generations.

Ayako Takahashi and I have translated these poems collaboratively, working together weekly over video chat since 2017. Ayako tends to favor a more literal translation, while I am often most concerned that the translations work as poems. Our hope is that we have landed someplace in the middle, maintaining with fidelity the vitality of the original works.

- Published in Interview, Monthly, Translation

FOUR POEMS by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Wago, Ryoichi. Since Fukushima. Trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi. Vagabond Press, 2023. Print.

Purchase the book here.

Screening Time

November 26th, 2011

—exiting the restricted area, a 20 km radius of the power station

screening palms

screening the back of my hands

screening with my hands up

screening with my hands down

screening over my head

screening the back of my head

screening the sole of my left shoe

screening the sole of my right shoe

screening my entire body

screening what is outer space

screening what is a hometown

screening what is life

screening what is radiation

to us

what is most precious

what cannot be measured

You

(no date)

precious

you

what are you

doing now

you are me

I am you

from the obsidian depths of night

it’s you I am thinking about

and for me

from me

you

I won’t give up on

for you

I won’t give up

JANUARY 7th, 2021

I swooned

reeled

reeling.

it was spring, one year after the disaster.

I boarded a helicopter and traveled into the restricted zone,

the 20 km surrounding the nuclear power station,

high above, looking over the land below.

from a perfectly kept beach,

we crossed into the forbidden sky,

as though we were trespassing.

the land left just as it was that day.

huge, concrete wave-breaks strewn on the beach.

houses, cars, and boats hit by the tsunami, scattered everywhere.

mud and stones spread across roads and fields, electric poles keeled over.

dogs chained at front doors and left behind….

time stopped.

no.

time doesn’t exist.

I remembered that.

dizzy. still now.

could be. the aftershocks.

which continue even now, I think.

the other day, I heard a story

from a dairy farmer living within 20 km of the power station.

“the cows were so hungry

there were teeth marks all through the barn and along the fences.

until the end, trying to find something to eat.

they wasted to skin and bones then fell over…”

*

“tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, getting by. an aftershock.

tomorrow, what will you be doing? tomorrow, like today, standing here. an aftershock.

a local broadcaster says, now everyone has heard of Fukushima. if we can recover, it’s an opportunity for us, he says. we’re known all over the world. an aftershock.

we clung to hope. tried to be grateful. is there a reward? maybe. but.

our families and our roots are here. famous around the world? I’ll burn the map.

an aftershock.

it’s calm. the night air, radiation. an aftershock.”

(March 22, 2011)

PEBBLES OF POETRY

Part 1: March 16th, 2011, 4:23 am —March 17th, 2011, 12:24 am

Such a huge catastrophe. I was staying at an evacuation center but I’ve now pulled myself together and returned home to work. Thank you for worrying about me and encouraging me, everyone.

March 16th, 2011. 4:23 a.m.

Today, it is six days since the earthquake. My way of thinking has completely changed.

March 16th, 2011. 4:29 a.m.

I finally got to a place where all I could do was cry. My plan now is to write poetry in a wild frenzy.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

Radiation is falling. It is a quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:30 a.m.

This catastrophe is so painful, and for what?

March 16th, 2011. 4:31 a.m.

Whatever meaning we can find in all this might come out in the aftermath. If so, what is the meaning of aftermath? Does this mean anything at all?

March 16th, 2011. 4:33 a.m.

What does this catastrophe want to teach us? If there’s nothing to learn from this, what should I believe in?

March 16th, 2011. 4:34 a.m.

Radiation is falling. A quiet quiet night.

March 16th, 2011. 4:35 a.m.

I was taught, “wash your hands before coming in the house.” But there isn’t any water for us to use.

March 16th, 2011. 4:37 a.m.

Relief supplies haven’t arrived in Minamisôma. I’ve heard that the delivery people don’t want to enter the town. Please save Minamisôma.

March 16th, 2011. 4:40 a.m.

For you, where do you call home? I’ll never abandon this place. It’s everything to me.

March 16th, 2011. 4:44 a.m.

I’m worried about my family’s health. They say that this amount of radiation won’t affect us very soon. Is “not very soon” the opposite of “soon”?

March 16th, 2011. 4:53 a.m.

Well, yes, there’s clearly a border between fact and meaning. Some say that they are opposites.

March 16th, 2011. 5:32 a.m.

On a hot summer day, I like to go to a beach on the Minami-sanriku coast. On that exact spot, the day before yesterday, a hundred thousand bodies washed ashore.

March 16th, 2011. 5:34 a.m.

In a quiet moment, when I try to understand the meaning of this catastrophe, when I try to see it clearly there’s nothing, it’s meaningless, something close to darkness, that’s all.

March 16th, 2011. 10:43 p.m.

Just now, while writing, I heard a rumbling underground. Felt the tremors. I held my breath, kneeled down, and scowled at everything swinging. My life or this tragedy. In the radiation, in the rain, no one but me.

March 16th, 2011. 10:46 p.m.

Do you love someone? If it’s possible that everything we have can be lost in an instant, then all we need to do is to find some other way not to be robbed by the world.

March 16th, 2011. 10:52 p.m.

The world has repeated both its birth and death, sustained by some celestial spirit which defies all meaning.

March 16th, 2011. 10:54 p.m.

My favorite high school gym is being used as a morgue for unidentified bodies. The high school nearby, too.

March 16th, 2011. 10:56 p.m.

I asked my mother and father to evacuate but they couldn’t stand to leave their home. “You should go,” they said to me. I choose them.

March 16th, 2011. 11:10 p.m.

My wife and son have already evacuated. My son calls me. As a father, do I have to decide?

March 16th, 2011. 11:11 p.m.

More and more people are evacuating from this town. I know it’s hard to leave. You can do it.

March 16th, 2011. 11:39 p.m.

Having evacuated to a safe place, the young man, twenty-something, is looking at the monitor and crying, “Don’t give up on our dear Minamisôma,” he says. What’s the sense of things in your hometown? Our hometown now, overcome with suffering, faces distorted by tears.

March 16th, 2011. 11:48 p.m.

Again, big tremors. The aftershocks we were expecting finally came. I was wondering if I should shelter under the stairs or just open the front door. Outside, in the rain, radiation is falling.

March 16th, 2011. 11:50 p.m.

The gas is on empty. Out of water, out of food, out of my mind. Alone in this apartment.

March 16th, 2011. 11:53 p.m.

A long rolling tremor. Let’s place our bets, do you win or do I win? This time I lost but next time, I’ll come out fighting.

March 16th, 2011. 11:54 p.m.

Until now, we carried on the daily lives of generation after generation, we searched for happiness, sincerity, I think.

March 16th, 2011. 11:56 p.m.

My elderly neighbor gave me a box full of onions. He grew them himself. Sadly, I’m not much for onions. The box sits in the entryway, I stare at it silently. A few days ago, I was living my ordinary life.

March 16th, 2011. 11:59 p.m.

12 am. Six days since the disaster. A sick joke! Six days since and for five days, I’ve wanted this all to be fixed.

March 17th, 2011. 12:03 a.m.

In the kitchen. Cleaning up scattered, broken dishes. Aching as I put them one by one into the garbage. Me and the kitchen and the world.

March 17th, 2011. 12:05 a.m.

No night no dawn.

March 17th, 2011. 12:24 a.m.

Ryoichi WAGO (1968–) is a poet and high school Japanese literature teacher from Fukushima City, Japan. In 2017, the French translation of his book, Pebbles of Poetry, won the Nunc Magazine award for best foreign-language poetry collection. Since March 2011, his writing has focused on the ecological devastation of the areas affected by the Tôhoku earthquake, tsunami, and the nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power station. Choirs across Japan sing his poem Abandoned Fukushima as a prayer for hope and renewal.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

Alive, the wind

lifts seeds

and carries them away

spider eggs hatch and depart on the wind

over years the wind breaks down plants into soil

we are of the wind and all of our senses

the wind breathing

through us

Within the Trees, A Universe

-Sacred Forest of Kinabatangan, Malaysia

people listen to the trees speak

the trees heard the people

there is light in the woods there was darkness

both life and death

there are voices and so there was silence

within the woods a universe

within the trees a human becomes human

A Mother Speaks

After seeing the noh play, A Killing Stone, Sesshôseki

the play starts in Nasuno province

on the stage there’s a thick purple silk cloth

covering a stone that was dropped

over a field like a cracked rotten egg

a bird flies over the stone and drops

dead to the ground, any living thing, person

or animal that touches that stone dies

a village woman tells the story of this terrifying stone

it starts with her failed attempt to take the emperor’s life

which left her spirit captured within the stone

that now casts spells on the living

when the stone splits open

the village woman appears as a ghost

and the dead return hatching through the stone

pulsing with energy stronger than even the living

the woman’s blaring red rage steadies

and fades to a pale color

the stone again becomes an egg

the defeated become the victors

the lost become found the dead revive

she speaks, the years steal from us

we are robbed of our eggs and escape to the wilderness

we give birth to stone children

hold them in our arms warming the stone

abreast of the thieves who stole our eggs

her ghostly feet glide stamp the ground

a voice within the mask scolds us

echoing from another world

will you be ruled by this bearing always

Rumiko KORA (1932-2021) was a poet, translator, and critic born and raised in Tokyo. Her book The Voice of a Mask won the Contemporary Poetry Prize in 1988. She also wrote essays and novels and co-translated an anthology of poetry from Asia and Africa. She devoted herself to promoting women’s work and was instrumental in establishing the Award for Women Writers. Much of her writing focuses on identifying the struggles and contradictions of a female gender identity.

Ayako Takahashi and Judy Halebsky work collaboratively to translate poetry between English and Japanese.

Ayako TAKAHASHI is a scholar and translator teaching at University of Hyogo in Japan. Her recent scholarship includes the books Ambience: Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene (Shichosha, 2022) and Reading Gary Snyder (Shichosha 2018). She has published translations of many American poets such as Jane Hirshfield, Anne Waldman, and Joanne Kyger, among others (Anthology of Contemporary American Women Poets, Shichosha 2012).

Judy HALEBSKY is a poet. She is the author of Spring and a Thousand Years (Unabridged) (University of Arkansas Press, 2020) Tree Line (New Issues 2014) and Sky=Empty, winner of the New Issue Prize (New Issues, 2010). She has also published articles on cultural translation and noh theatre. She is a professor of Literature and Language and the director of the MFA program at Dominican University of California. Ayako and Judy have been working together for several years and have previously published articles in ecopoetry and English language haiku.

- Published in Featured Poetry, Monthly, Poetry, Translation

J

J