shows on homepage

INTERVIEW WITH Clifford Thompson

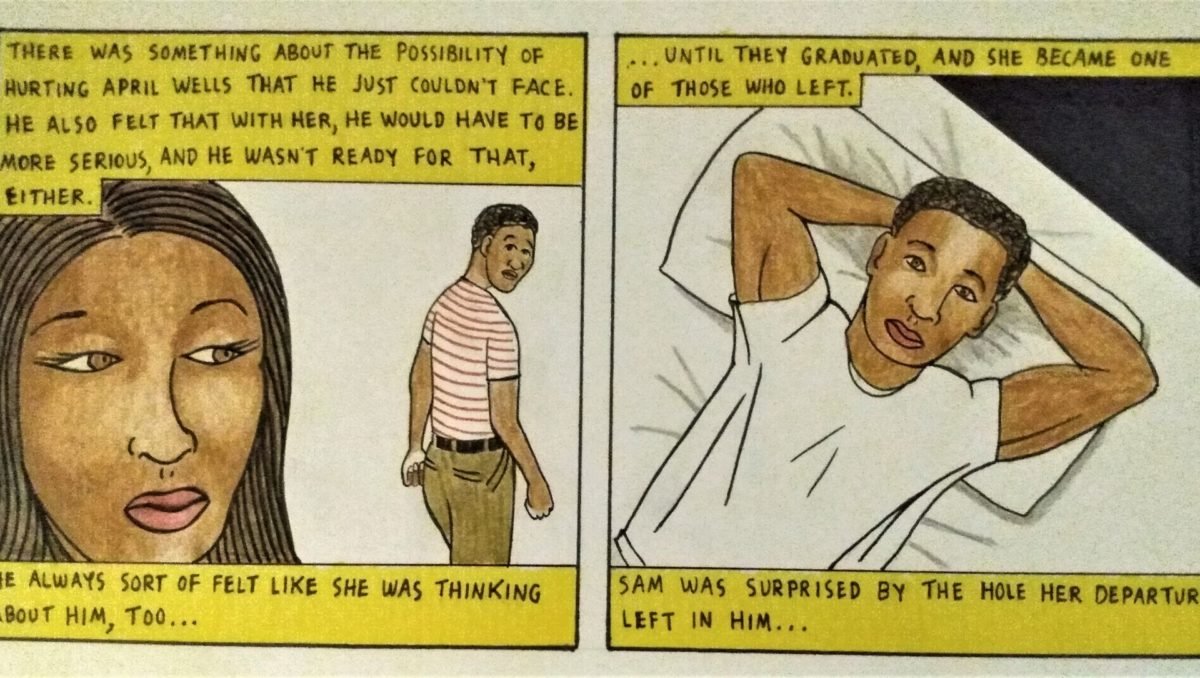

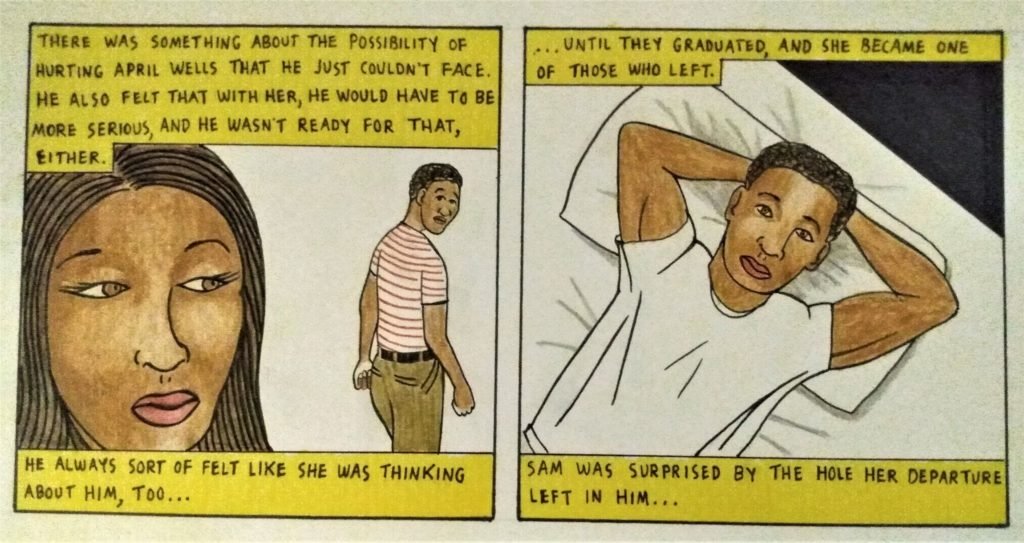

Clifford Thompson is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award for nonfiction in 2013 for Love for Sale and Other Essays, published by Autumn House Press. He has also published a memoir (Twin of Blackness), a novel (Signifying Nothing) and a nonfiction book (What It Is: Race, Family, and One Thinking Black Man’s Blues). Thompson’s graphic novel Big Man and the Little Men, which he wrote and illustrated, is due out from Other Press in Fall 2022.

FWR: Having read a lot of your fiction and nonfiction, I was excited to hear that you’re publishing a graphic novel, Big Man and the Little Men, due out next year from Other Press, which you’re writing and illustrating. What does this process look like? Do images come for you before writing, or vice versa? Many writers map out ideas through drawing. How does creating your own illustrations affect your writing process?

CT: I begin by writing. The script comes first. The images are in my head, if only hazily; I’ll write, for example, “Three-quarter view of men on right side of the table.” But I don’t put those images on paper until the real illustrating begins. The script is largely a series of IOUs to myself. That is, it’s easy to put in the script, as I did at one point, “Drawing of a baseball game.” The payment comes due, you might say, when it’s time to illustrate that panel, when I sit at my drafting table and think, “Oh. Right. Now I’ve got to draw a baseball game. How do I do that?” So as a writer I put myself in positions that I then have to draw my way out of. In that way, there’s a certain amount of improvisation involved. (I find it hard to resist allusions to jazz.) For example, when it comes time to draw those men on the right side of the table, I may decide as I’m drawing that one of the men is giving the other a sidelong glance.

FWR: The prose in a graphic novel has to be so crisp and focused on action. How do you work within these limitations? Do you overwrite, then whittle down, or do you have other methods?

CT: One challenging thing about a graphic novel is that there are practical considerations of the kind you don’t run into with a regular novel, or even with painting. One is that you can fit only so many words in a panel. So I may discover, as I’m doing the actual lettering for the dialogue I’ve written, that not all of it will fit, or at least not comfortably. Then it’s a matter of rephrasing the dialogue, retaining its flavor while making it as concise as possible. Sometimes I end up improving it, almost by accident.

Writing and painting are similar for me in that the idea is half the battle. Once I have an idea, the challenge is to find the best way to carry it out.

FWR: How does starting a written piece compare to drawing or painting? Has your graphic novel bridged these two approaches, or does it feel like a different approach entirely?

CT: Writing and painting are similar for me in that the idea is half the battle. Once I have an idea, the challenge is to find the best way to carry it out. When I’m writing, that often involves lists. I’m a big list-maker, especially when it comes to essays. I like to list aspects of the subject I want to write about, then study the items on the list to see what the connections exist among these seemingly disparate things or ideas; I’ll draw arrows from one thing to another. Sometimes I find a lot of arrows going to the same item, and that can be a sign that I’ve hit on something. For paintings, once I have an idea, I pull out my sketch pad and work out the composition, the proportions and relative positions of everything. I have the sketch-pad drawing next to me when I make pencil outlines on the canvas.

Again, the graphic novel begins for me with writing, but I would say that the graphic novel bridges writing and painting in that the written and visual aspects of the work spell each other. The graphic novel is a visual medium, but you need words. You just do. Even Kyle Baker’s terrific graphic novel Nat Turner, which is almost all pictures, uses some words. Still, some of my favorite moments of working on Big Man and the Little Men are when I can draw a panel or series of panels that speak for themselves. A motion, a facial expression, a character’s eyes looking in a certain direction, three people’s heads turning toward a fourth person who has just uttered a non-sequitur, a hug between two forty-year-olds who last saw each other in high school—panels like that can say it all. Not a single word needed. I find that satisfying.

I’ve been painting now for years, which has come in handy with the graphic novel because of all the time I’ve spent shading with colors in painting. To a certain extent I’ve transferred that process to the graphic novel: I shade with colored pencils, darkening some areas of a face, for example, while taking an eraser to other areas. That is one thing I didn’t do when I was drawing comics in high school, oh so long ago now.

A friend of mine, looking over the pages of Big Man that I’ve illustrated, observed that my unit of visual expression—he said something to that effect—is not so much the individual panel as the page. I think that’s accurate. The page comes together to form a kind of statement.

FWR: Your Four Way piece, “Quintessence,” ponders creativity—where inspiration comes from, how and why we write what we do. You’ve written a lot about music, film, and visual art over your career. Some of your artwork has a tone that resembles Augusta Savage or the stark lines of Elizabeth Catlett, another DC artist. How do other artists, writers, or their mediums inform your work?

CT: I appreciate the comparison to those women. I find that I like two things in visual art: color and simplicity. The work of the Fauves, and artists such as Catlett and Jacob Lawrence and William H. Johnson, greatly appeals to me for those reasons. In some graphic novels I read, I admire all the detail the artists put in as well as the artists’ technical ability; still, because the images are so lifelike, with so much going on, sometimes my eye doesn’t know where to go. So I try to put in a few details but focus largely on color, composition, and the central image.

When it comes to writing, I am never consciously aware of being influenced by others’ work, but sometimes people see things in your writing that you don’t see. In my book What It Is, I write about James Baldwin and Albert Murray, among others. The reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement wrote that I had blended, “consciously or not,” the “voices of [my] mentors Baldwin and Murray.”

FWR: In The Rumpus earlier this year, you explained: “It could almost be said that much of my work is an attempt to solve a puzzle.” In Big Man and the Little Men, a writer becomes enmeshed in a presidential campaign when an accusation is made against the nominee. What puzzle pieces are at work in this book, and how did you decide what form they would take?

CT: I think the puzzle at the bottom of Big Man is: how do you do the right thing when there seems to be no right thing to do? That’s the quandary that my main character, April Wells, faces. As for deciding on the form, I’m not even sure I did. The idea came to me fully formed.

FWR: I wonder if you can elaborate on this. How do you move between more planning-oriented techniques—like your lists, arrows and IOUs—to more intuitive ones? Or are you describing more of an organic gradual process of both, one feeding the other?

CT: Maybe a good analogy would be carrying out a military or spy mission (not that I have ever carried out either of those). That is to say, you can make lists and draw arrows and write IOUs, just as you get instructions for a mission; but doing the thing is where it happens—the fun and the risk, the difficulty and the discovery, the improvisation and toil and surprise.

FWR: You’ve written often about politics, including in What It Is, and most recently in a series of essays for Commonweal Magazine. Big Man too is interested in the political. Do you have any craft tips or observations in terms of how you approach political writing across forms?

CT: You know what’s funny? Until I read your question, it hadn’t occurred to me that I’ve written often about politics—maybe because the works you mention are all so different from one another. But you’re right, I guess I have. And I guess the reason is that presidential politics have fascinated me since the first election I remember, when I was nine, when McGovern ran against Nixon in 1972—still the gold standard for lopsided election results. (I’m proud to say I’m from Washington, DC, one of two places in the whole country that McGovern carried.)

I don’t know if I have any craft tips for writing about politics, but I do have one observation, which is that, fundamentally, nothing is new. That may be a good thing to keep in mind when writing about politics. So maybe that is some kind of tip, I don’t know. But here is an example of what I mean: The first five presidents of my lifetime were John F. Kennedy (who was killed when I was eight months old), Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter. Not one of those men served two full terms, and a couple of them didn’t even complete one term. So for my entire childhood, the American presidency seemed like an unstable thing. Then, for decades after that, with the single exception of George H. W. Bush, the presidents were two-termers: Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush, Obama. Then, of course, came Trump, demonstrating the cyclical nature of politics. For all the sheer, seemingly unprecedented god-awfulness of the Trump years, his shenanigans and defeat were almost like a return to my childhood. It was sort of like when people used to go into movie theaters in the middle of the movie and stay for the beginning: “I remember this—this is where I came in.” (That said, I pray that this round of chaos ended with Trump. I wish President Biden great good luck.)

FWR: Sometimes when I read your work, I’m reminded of Virginia Woolf’s concept of caves. Ideas, characters, or narratives which seem disconnected, eventually, as Woolf describes it, “connect and each comes to daylight at the present moment.” How does this process of braiding seemingly disparate elements into a single narrative work for you in making a graphic novel? Is this different than in your writing fiction or nonfiction?

CT: I am delighted by that characterization of my work, and I’ll take a comparison to Virginia Woolf any day of the week! I would say that the braiding happens more in my nonfiction, and yet, now that you mention it (you ask very good questions!), I see that there is braiding at work with Big Man. The story’s prologue has two scenarios involving different sets of characters, with no indication of what they have to do with each other. But later it becomes clear.

FWR: What’s next for you after Big Man and the Little Men?

CT: Time will tell. I have several manuscripts in various stages of readiness. One is a manuscript of poems. I said to my wife that I’m working toward publishing one of every kind of book—a joke, though not really.

Ghinwa Jawhari on her debut chapbook: BINT Interviewed by Sara Elkamel

Ghinwa Jawhari named her debut chapbook, selected by poet Aria Aber for publication by Radix Media, BINT, Arabic for girl. In Arab cultures, the word is also used to describe a virgin woman, of any age. In this series of poems, compact in form yet unbridled in lyricism, Jawhari explores the passage (particularly of those in Arab diaspora) from bint to woman: its wounds, its pleasures, and its inevitable reverberations on societal and self perception.

Jahwari is a Lebanese American writer (and practicing dentist), currently living in Brooklyn. Born to Druze parents in Cleveland, she grew up listening to poetry from her father, who often recited traditional poetry in Arabic, or Zajal, around the house. In middle school, she wrote little poems and saved them in spiral notebooks, before going on to study English, alongside chemistry, in undergrad. Over the past few years, her essays, fiction, and poetry have been featured in Catapult, Narrative, Mizna, The Adroit Journal, and other publications.

As an Arab woman myself, I found an incredible kinship with the speaker(s) in Jawhari’s poems. The opening poem, titled “condition”, piercingly captures the strain stepping into womanhood places on our relationship with our fathers; “when you had the sterile body of a child / you were loved by your father / now you’re grown”, she writes. For me, the erosion of the father’s unconditional love in tandem with the girl stepping into the body of a woman could not have been captured more poignantly, more resonantly.

And it’s not just the speaker’s voice that was familiar. Many of the poems in BINT have Arabic titles, and are decorated with objects that I myself grew up around—prayer beads and “blue eyes hung over the door”; the Mediterranean, which Egypt has in common with Lebanon—carrying the bodies of the girls in Jawhari’s poems. When we met (online) to talk about her stunning chapbook, Jawhari told me that it was her intention to write BINT for readers who would relate to it. “When you say to yourself: I’m going to write this to my sister or my cousin, suddenly it frees you to do whatever the hell you want to do,” she said.

In the interview below, Jawhari reflects on her insistence to avoid writing towards the white gaze, and shares the thought processes that led to her choice of form, language and imagery for BINT.

Sara Elkamel: I found an incredible tension between divulgence and restraint in BINT, in terms of both language and form. But I’d like to start by asking you specifically about form. Even though you’re tackling these expansive subjects that could probably fill notebooks—including queerness, intimacy, and what being a girl, or a woman, means to you—the poems materialize in these really slight, compressed shapes on the page. How did you arrive at these forms for BINT?

Ghinwa Jawhari: First, the chapbook was written for people who already know what a bint is. It’s not written for the white gaze. I didn’t want to spend time explaining the context. I was trying to figure out how to get across, in the smallest amount of words, facts central to our lived reality as girls—like in “counterfeit,” the poem about getting sewed up to ‘restore’ her virginity; becoming “regirled.”

And secondly, the form was informed and constrained by this project being a chapbook. I was at home during the COVID outbreak, and it was the first time I wasn’t working in a long time. I was excited to be sitting at my desk every day and focusing on a single theme. Because I knew it was going to be a chapbook, everything had to lend to brevity. It’s less than 30 pages—so in order for the pieces to work together, they all had to be concise. They’re in conversation with one another.

Sara Elkamel: I’m intrigued by this choice of not writing towards a western gaze—especially since Arabic words often appear in your poems, most notably in the title, BINT, which means girl, yes, but also signifies “virgin” in our culture. As poets, I think that sometimes when we use Arabic, we feel the need to explain or translate what we’re saying as we say it, which can very well get in the way of the poem. And I’ve definitely done that in my work before.

Ghinwa Jawhari: Yeah, I’ve done that too! So much of my work before BINT was me explaining. But when you begin to dismiss that, and when you say to yourself: I’m going to write this to my sister or my cousin, suddenly it frees you to do whatever the hell you want to do. You become far less concerned with “Does it make sense?” and more attentive to “Is this true?” It’s no longer: “Will somebody understand me?” but instead, “Will the people who already understand this context agree that this is what happens?” So it’s all a focus shift.

Sara Elkamel: I definitely related to the bint you gave us—at once susceptible to cultural forces and forceful in her own right. I was especially drawn to the verbs you associated with the body.

without consent my small body erred

into hair-tainted womanhood, polluted me

with breasts. i begged for men, any men,

to appear from the fog of my dreams.

In “instead a palace”, for instance, there is some kind of agency—the body itself erring—coupled with a vulnerability to external perception; “polluted me” gestures towards what womanhood does to the body in the eyes of the street. Then in “a girlhood summer passes”, you turn towards illustrating the intimidating power of a girl’s body with a line like: “our slim bodies assault / the surface of the water”. So I’m wondering about these minor choices you made in language, specifically your wiedling of verbs.

Ghinwa Jawhari: I love that you asked about that, because I paid so much attention to the verbs—changing nouns into verbs, being very careful and earnest with what kind of verbs I used. I was trying to capture the body as an embodiment of what the outside world wants it to be. In the earlier poems of the chapbook, I was thinking about how a girl’s body is essentially a socio-political construct; the body is cultural. We can’t escape it—it happens to us. It’s not something that I have agency over. Versus in the poem “condition”, which comes at the end of BINT, when finally there’s a turn. I wouldn’t say there’s redemption—I think that’s simplifying it a bit. But at the end, the women can kind of make light of the fact that they have arm hair, make fun of virginity, and choose to drink.

girlhood an illustrious specter, then.

we pass through & barely remember

its tightly wound calamities, its fears.

as women we lace our mirth with liquor.

virginity an elaborate antique, unfashionable

as arm hair. we rid ourselves of last names.

So the girl body is what’s constructed, and constricted—it’s the thing that has to be decorated, preserved, defended and instructed what to do—whereas the woman body has some agency, holds space to become different, something self-directed.

Sara Elkamel: I admire how you’re really digging into the different layers of what makes a girl a girl. The poem “counterfeit”, for instance, invokes the economy around girlhood.

my father pays the surgeon to return me a bint.

in an hour i am unruined, regirled.

I also love this poem because it feels very playful—even though it’s essentially very dark. I think readers who don’t share our culture would be horrified that these surgeries take place. But you’re like, yes, this is happening. Right now. In this poem. I also really enjoyed the invocation of role-play.

this time i know the value of a counterfeit

so i behave myself, role-play. all of it a trick:

honor restored as if it can ever be,

worthless masquerading worthwhile.

It feels like the speaker is hyper aware of performance and performativity; that “worthless” and “worthwhile” are both nothing but costumes that we put on. As you were tackling such brutal subject matter, did it feel manageable to still experiment and play?

Ghinwa Jawhari: The final draft of that poem came out playful by accident, in a way. When I started it, all I had was “worthless masquerading worthwhile.” Whenever I write a poem, it always starts with a single line, and then it grows out from there. So the initial concept revolved around this charade: A hymenoplasty restores a “false” virginity, intended to be perceived as true. So what is virginity if it’s this easy? I think the playfulness might stem from the bint’s nod to this as a cosmic joke we play on the body, sewing it up and asking others to pretend along with us. It states pointedly that these concepts are fake to begin with.

And it is pretend. It’s roleplay. You’re roleplaying a woman, you’re roleplaying a virgin. And Arab women, I think—or SWANA women in diaspora—understand that there are tricks we have to learn to play. We shed these selves all the time. If you’re going to your family’s house, and you’ve just been out drinking and partying, and you have makeup everywhere, the first thing you think is: I need to get clean and look like I wasn’t anywhere. Like I was studying. We’re all familiar with that. To roleplay the perfect daughter, we are not 100% honest about our identities with our families. Because if you’re doing anything that doesn’t subscribe to what they perceive that role to be, it’s wrong.

So that was always at the back of my mind—that a lot of being a girl, especially when you’re young, is lying. We can say pretending, too: pretending to like something, pretending to be feminine, or obedient, pretending to behave oneself, so to speak. I’m 30 now, but I wrote this when I was 29. So I was at the cusp of that old maid, unmarried title. Another role! I was just so fed up with it, because it’s nonstop. So one way to subvert these expectations is to add humor, or make the reality playful and ridiculous, because it is.

In order for us to survive, anyway, we have to undercut the seriousness of things. And that’s kind of the thread through the chapbook: despite what they’re telling us, it’s not that serious. That’s almost the saving grace. We have to tell ourselves: I’m fine. I’m going to be okay. Even if I don’t fit every single role the way they’re telling me I have to.

Sara Elkamel: I am also very interested in the way you play with bodily organs and animals in your poems. In “winter of the acned year”, your invocation of animal slaughter really struck me, particularly because it shares space with a trace of the speaker’s late night masturbation.

beneath the quilts piled on us, i silenced with my hands

the loud wet thing that would not let me sleep

pawed myself to dog-panting at the remembered eyes

of the man who had slaughtered a ram before me

I guess this poem made me think about the proximity of intimacy and violence in your poems; here, we’re given this very solitary fantasy, and the deceptive tenderness of the man’s eyes, before a sudden transition towards sacrificial slaughter. Your choice of couplets for form also brought the tenderness and the violence even closer together, which I found very moving.

Ghinwa Jawhari: I love this poem. It actually started out as one huge paragraph, and then I cut it into couplets. I think my reading of this poem—and it could be a wrong reading, even though I wrote it [laughs]—is that it’s a time when you’re kind of acned, not really mature, not fully into your sexual-ness yet. You’re beneath a heavy quilt, which is supposed to keep you warm, but is also restrictive, and you’re silencing yourself with your hands because you’re horny—you don’t know why. And it all has this closeness to the violence of sacrificial slaughter. But then the violence against the animal is halal, so the speaker must be thinking that sex should also be halal, in a sense. Like, how come the slaughter is halal but what I’m doing to myself, to give myself pleasure to go to sleep or whatever, is not halal, right?

i watched the butcher disassemble the animal from the car

over his head, halal insisted in red coils no wrongdoing

my mother, returning to the driver’s seat, appetited for its glistening liver

the organ in white paper followed us home, where she cubed it into meal

i recalled its size, its flab texture, the bleat

its oil swarmed my mouth like a vow

And then you have the mother in her very own couplet, interrupting it all. Interrupting the slaughter, the violence, interrupting the fantasy, the pleasure—suddenly, you’re completely removed from the fantasy. Your mom jumps in and asks ‘hey, do you want to get this liver?’ And the organ is wrapped in white paper, suggestive of something bridal.

But anyway, I don’t think violence and sexuality are separate. You can have very violent, not pleasant sex in spaces that are not comfortable or tender. That exists. Western perceptions of sex—the sex in movies or music videos—is tender, haughty, controlled. I think, especially if you’re in a conservative space where girls are marrying guys they don’t know well, or when it’s an arranged thing, sex and violence can very much be one and the same. It’s not like there’s intimacy, and then there’s violence. No; there’s intimacy plus violence, especially if you’re queer—you learn to anticipate aggression in regards to your sexuality or in regards to how you’re identifying or existing. So I guess this poem is not bridging sex and violence; it’s making a statement that they can be the same thing. And it’s unfortunate that we’re kind of trying to think of them as separate, because then when we do experience sexual violence or intimate violence. We are in shock, and we wonder how this can happen.

Sara Elkamel: I’m interested in the way you manage to talk about violence without talking about violence, you know? I think your use of devices such as play and figuration, along with loose narrative, all works to create a space that remains other-wordly in its tackling of the worldly. I’m particularly curious about your use of surrealism to talk about very real experiences.

Ghinwa Jawhari: Surrealism serves to depersonalize the body, in the sense that even the speaker can objectify her own body. Saying “I detach my hand” [in the poem “tazahar”] renders the body figurative and distant, so we can ask “What does the hand symbolize?” Here it is alluding to a hand in marriage, but there can be other meanings. I don’t know how much surrealism appears in my work in general, but there’s a sense, in this poem at least, that the bint is suspended, looking at everything around and within her as if for the first time.

what a doll i was those years after the towers

fell. i went blonde as one goes insane, womaned

with a new name, an easy olio for the tongues

that tsk’d me. gone were the guttural

consonants, the hairs connecting my brows.

i starved my hips. i wore english like a ring

until men begged my father for my hand.

i detached my hand & gave it to him, a fishing

lure. a prophet arrived to open the leaves of me.

A sort of war-born surrealism also features in the poem “a girlhood summer passes,” where these girls are hanging out as the war is just going on around them. It closes with them swimming during a ceasefire. But I was in Lebanon in 2006, and that was kind of a reality; whenever there’s a ceasefire, you just go hang out.

Ultimately—I think because I’m working on these longer projects—I am now exploring the magical more. You can use it to say more, without flat out saying: This is wrong. Even though it is [laughs]. But it’s difficult, because if you make it too magical, then it’s completely fictional. And nothing is completely fictional. It has to come from somewhere. I wish I could’ve done more with surrealism in this collection; but the deadline was coming up!

Sara Elkamel: I’m still so impressed that you wrote this entire chapbook in two months!

Ghinwa Jawhari: It’s my ADD. And now I won’t produce anything else for 10 years.

Sara Elkamel: We’ll wait!

CONVERSATION WITH Adrian Matejka and Conor Bracken

Adrian, thanks for agreeing to talk about your latest book, Somebody Else Sold the World, with me. I’m really excited to talk about it, and the ways that it is contiguous with your larger poetic project, and how it also subverts or cuts new facets into it.

One of the things that has always exhilarated me about your poems is their music. The title is from the David Bowie song, “The Man Who Sold the World,” and many of the poems in the book itself refer to/are in direct conversation with a wide variety of songs and artists (Future, Radiohead, Thundercat, Funkadelic, Tycho). (Clearly your taste in music is as catholic (eclectic wouldn’t do justice here) as it is good). But the poems are as deft and musically double-jointed as ever. Assonance and alliteration, stutter-step rhythms and sudden spans into smoothness–sometimes it feels like what Dilla might have done with a typewriter instead of turntables. The relationship of music and poetry has changed a lot over time–no more lyres, for instance. How do you think of and work with the relationship between music and poetry in your own work?

Adrian Matejka: Conor, man, thank you for taking the time to read the book and for your kind words about the poems. It’s wild because almost every poet I know is a failed musician in one way or another. Either they weren’t especially gifted musicians (like me) or they decided to employ their musical talents in different ways, like Mari Evans and Terrance Hayes. Thomas Hardy supposedly got down on the accordion, too, but that could also be a myth.

The thing is poets are musicians, we just use assonance instead of adagios. One of the great things about our current poetry moment is the incredible musicality of the work. I’m thinking about [your full length] The Enemy of My Enemy is Me (congratulations!!!) and the poems in the book (like “Kintsugi”) that just swing. And Kendra DeColo’s I Am Not Trying to Hide My Hungers From the World and World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. Hanif Abdurraqib’s sonics in both his lines and his sentences and Ross Gay’s astonishing Be Holding. So much bright music around us. Then there are books with quieter compositions that still astound, like Erin Belieu’s Come Hither Honeycomb, Alex Dimitrov’s Love and Other Poems, and Shara McCallum’s No Ruined Stone. I guess I just started a 2021 reading list instead of answering your question because there are so many new books that hum right now.

Maybe one of the reasons I lean into music so directly is that music has been a constant in my life. I played middle-school French horn terribly, was on the mic with a band in college, and DJed on the radio for a while. But when I was a kid, we lived next to a blind woman named Pearl who would listen to music at all hours—jazz, soul, and funk especially. I would wake up in our brokedown townhouse in the middle of most nights because every creak in that space sounded like someone breaking in. I got so much comfort from hearing Pearl’s music because it reminded me that I wasn’t alone.

That’s when I learned about the possible comforts in music. I’m not sure if there’s a direct connection, but I know for certain COVID made me hear lyrics, hear bridges and solos with a different kind of attenuation. I mean, I’ve always loved Portishead’s Dummy or Dexter Gordon’s One Flight Up but the sounds seem differently focused after isolation. Have you had that experience, too? Where something you understood one way has changed wildly after COVID?

CB: Oh absolutely–COVID definitely shifted some things in my life a couple degrees so they were like that woman’s arms in Prufrock–in the lamplight downed with light brown hair, i.e. different, a little more intimate and real. The largest was probably isolation. Before the pandemic hit, my wife and I moved to a small town in central Ohio that was right between our jobs (each about an hour away). We lived for a couple years without family, friends, any sort of social network, and it was tough. During the pandemic, it was still tough, but we’d been accustomed to not seeing anyone, so our social isolation looked different: not so much a condition, but a preparation. This didn’t change isolation to some magical wonderthing, though–it’s hard to rely on one or two people as your only relief from yourself.

Another thing the pandemic shifted for me, both slightly and enormously, was parenting (my daughter was five months old when lockdown started). I got to do a lot more of it than I would have otherwise! This was great, and also taxing, as you well know. Parenthood, along with the pandemic, is also one of the narrative/thematic threads in Somebody Else Sold the World. The Gymnopédies suite is sweet, pithy, and beautiful, shot through with a nostalgia that seems really right for an homage to [French composer] Erik Satie, and those poems, along with “Snakes Because We Say So,” help the speaker reflect on change–in the world, post-pandemic, as well as in himself. “Snakes,” in particular, is such an interesting and delicious poem——it has so much! The anaphora, the question about blame and its necessity, the interrogation of masculinity, the tone flicking its tail this way and that–but I’m especially curious about how you approach poems with your kid in them. I remember hearing Victoria Chang say something akin to (but kinder than) “my kids? I’m with them every day. Why do I want them in my poems?” Do you end up consciously writing about parent/fatherhood, or is this something that just kind of happens?

AM: What Victoria said cracks me up for so many reasons, but especially the exclusiveness of, or maybe the pervasiveness of being a poet. It’s so complicated and consuming. There are poems I’ve written that are only possible because of my daughter and then there are poems that never made it onto the page because I’m a father. Something is begetting something, but I’m not sure of the direction.

A while back I was working on a book of essays/poems about being a Black father during the Obama presidency and after. I gave up on the project for ethical reasons (including ones connected to the ownership of story) and also because there were some generational contextualities that I couldn’t unpack. I was raised in a generation still limiting itself with the one-drop paradigms of race. My daughter and her friends don’t go for those same constructions, so writing about Blackness and fatherhood in that context ended up being more historic than familial.

After I left the house, my relationship with my daughter fractured for all of the familiar reasons and I don’t feel like I understand [those threads] well enough to talk about it. But I think that breaking happens across our lives, all of the time. It’s impossible to change locations and be the same person. We move or a friend, family member or paramour moves, and our relationships change because of new topography. We have no choice but to change with the new atmospherics on all sides. Maybe you’re experiencing some of this in Ohio after so much time in Texas?

That’s a long way to go to say that the poems you mentioned are among the seven poems I wrote pre-pandemic while I was working on that earlier project. Everything else in the book was written between March and October 2020. The experience of isolation from the world and from my daughter made me reflect on what connections we still have. The Gymnopédies poems were part of that reckoning, if that makes sense. Thinking about the things we shared when she was six or seven, rather than the things we can’t communicate about now that she’s a teenager. There’s a different veneer to everything.

I’ve been thinking about how isolation has eroded our delicate nettings of socialization. I enjoy a good in-person poetry reading as much as the next poet, but it took me years to figure out how to separate my creative and public selves. I had to learn to change from my usual poetry lens to one that is more social so I wouldn’t sound like a T.S. Eliot parody at the party, affected British accent and all. I mean, there has to be separation, right? Nobody actually wants to sound like a poem during a conversation.

It feels like maybe a year of Zoom readings erased my etiquette on the page and off. I’m not sure I can still do small talk. Time in poems works differently now. Urgency in the world seems even more vital now.

I had a psychology professor in college who might have been British and was dosed with LSD without knowing. He became obsessed with time afterward and either lectured to his watch or to the clock on the wall, so he always knew what minute it was. It’s not that dramatic as that, but all of the past year’s mortality and stagnation has me thinking about what progression is when the world stops. I’m wondering about the different versions of mortality in The Enemy of My Enemy is Me, too, so I hope you’ll talk about that some.

CB: Oh, that’s so interesting about the Gymnopédies poems being kind of grafted onto/woven among poems that were written just last year. I remember seeing some of them years ago in POETRY (around the time The Big Smoke was out) and thinking ‘whoa these are so different–not coming over a sound system in a basement or from a podium but from someone leaning down to say something private and intimate.’ That they fit so seamlessly with the rest of the book, and its themes of time, distance, intimacy, and regret/guilt, speaks a lot to your revision and curatorial process.

That anecdote about the furtively-dosed prof–holy shit! LSD is, uh, quite a thing to weather when you consent to it; I can’t imagine what it’d be like to be hoodwinked into it. It seems like an apt metaphor/allegory for the pandemic, in a way: a mind-altering experience we had no idea we were participating in, could not escape, and are now greatly changed by. I love that you bring up time as one of the things that it’s changed for us, too, because I think another of Somebody Else Sold the World’s big fascinations for me is how it interrogates the themes I mentioned above in the context of different temporal cycles: the pandemic, the cycle of the year, the cycle of relationships (romantic and familial), and a human life cycle. How you toggle among these four, their different intimacies and terrors and exhilarations, and how they share so many of these between them, is really deft. It’s like watching the innards of a watch click and spin, all of these interlocking and meshing, driving the thing forward in a dazzling mess of glints and thoughtful friction.

I’m always so interested, too, in the way that time can work in a poem, and how it can both defy and encompass the way it does so in our world. I heard Noah Warren read a poem that leapt over like twenty years when he read the line “the years passed badly” — suddenly we’re in a future we didn’t know the poem was even capable of. I love how poems can do that. And how they can rewind time, too, like Ansel Elkins’s poem reversing a hate crime and restoring humanity to the victim of a lynching.

I want to ask you about time in your poems, too, but also want to answer your question about mortality. I mean, it’s more present for so many more than before, right? Between the stormier sky, the rising oceans, the hotter winds, and the cops, filmed or otherwise, brutalizing people of color, not to mention the virus and equitable medical care receding via cost and abortion restrictions, if it’s not already gone due to differential treatment of Black folks by science and practitioners–the urgency to address these has been there, but it definitely feels of a different order now.

As for my book, there’s a lot of violence in it. (Any book that takes the US as part of its subject will, or ought to, right?) There’s violence on the international level, the ecological level, the interpersonal, and the intrapersonal. The quote-unquote regular kinds of mortality, about the actual death of a person, come through with US neoimperial campaigns (the speaker is a paramour of Henry Kissinger, who helped engineer all sorts of coups and illegal bombing campaigns in the name of democracy) and mass shootings/gun fetishism; the other kind of mortality that the poems look at are what selves we are asked to sacrifice by society, specifically the kinds of selves it expects men (especially white men) to get rid of, and how restrictive, violent, and regressive this shedding of more thoughtful or conciliatory selves that do not want to participate in or overlook toxic instantiations of male personhood is.

I’m interested in complicity, how we can see cruelty, know that it’s perpetrated on our behalf, and allow it to go on. What kinds of deaths inside us does that engineer? What do we need to strangle inside ourselves so that we’ll stop a strangulation we are seeing?

This seems to me something you’re looking at, too, in Somebody Else Sold the World, albeit from a different vantage, different because of how race works in our poems and poetics, not to mention our lives, especially if/when we take race as a proxy for how the world does (or does not) impose itself on us. You also seem to be asking how did we get to this particular place of injustice, and what is that doing to us? Tiana Clark recently talked about each book having an unanswerable question as its engine. Does that hold true for you, or do you center the process differently when you are beginning a book?

I love to imagine that poetry is an antidote to all of this, but it’s not. It’s a signifier or an amplifier—more like a megaphone at a protest than a gun.

AM: Complicity is so knotty and multifaceted because it can be, as we’ve seen forever in the United States, something that people deny defensively, ignore selfishly, or sidestep quietly. I’m thinking about this wide lensed, in our public institutions, too, where cruelty is baked in and called “bureaucracy.” But it’s also been in the backdrop of my personal interactions since I was a kid. When I was younger, I rode shotgun with friends who enacted some of the toxicity so many of us (including some of those now-repentant friends) are trying to break apart now. That’s a familiar history for many men. So until each of us figures out how to be less selfish and avaricious, how to move through the world making space instead of taking it, we’ll continue to have these problems of disparity and disempowerment that’s been protected by our patriarchal systems.

Now I’m thinking about one of the poems that didn’t make it into SESTW that was inspired by a high school boy I knew when I was in middle school. He used to hip me up to the goings on in the neighborhood and in life generally, the way older kids sometimes would. Most of what he said was harmless and was probably repeating what he was told when he was younger. But his advice about women was essentially “make no mean yes.” He was passing on these ideas of sexual assault that were common then and now. I was 13 at the time and didn’t understand what he was saying until much later. I don’t think I was alone in being offered that kind of destructive advice from other men.

I love to imagine that poetry is an antidote to all of this, but it’s not. It’s a signifier or an amplifier—more like a megaphone at a protest than a gun. The poem I wrote about that guy wasn’t any good in part because of Tiana’s beautiful idea of unanswerable questions. There are no questions about his abhorrent advice beyond “Who taught him this?” so the momentum disappeared and what I had left was a didactic anecdote in line breaks.

But some of the major questions I kept asking myself in this book are about desire and want and also about consent and agency. I think the answers to these questions are constantly evolving, but I hope I started to answer them in SESTW.

At the same time, I don’t know if this book does the tough work of trying to dismantle the kind of cruelty we’re talking about at the top. I am fully aware of my position as a middle aged, heterosexual guy and American poetry from the 20th century on through is clogged with covetous, slobbery poems by men. I didn’t want to add to that self-serving canon. If anything, I hope that I was able to think about desire as part of the human condition, as familiar and as vital as breathing. Now I’m thinking about other poetry collections that deconstruct masculinity. Edgar Kuntz’s Tap Out does. Keith Kopka’s Count Four and Marcus Wicker’s Silencer do as well. Who else?

How do you write a love poem in the 21st century? How do you write a poem about sexuality and desire while also respecting the person who ignited it?

CB: Making space instead of taking it–so well said. It makes me think of that Mark Strand poem, “Keeping Things Whole,” in which the speaker says “In a field / I am the absence / of field.” That poem–like so many of Strand’s–works because it has a kind of moral revelation in the midst of an alternate dimension. You’re trying, in SESTW and just generally overall too, to do this moral work in the world we’re a part of. Not trying to diss Strand, but note an important qualitative difference, because one of the things that I think can be so hard is doing this so that the poem doesn’t just become a didactic anecdote in line breaks. How can the necessary distance between poet, speaker, and subject come into play so that the materials of the poem can be moved around until they click (or rattle right)? For me, I had to take the Strand route–go a little surreal with it, lean more into persona so that I wasn’t frozen by my closeness to it all.

But books like Edgar Kunz’s and Marcus Wicker’s (I haven’t read Count Four yet but have to), and Nathan McClain’s Scale, some of Shane McCrae’s less persona-driven work, even Hanif Abdurraqib’s A Fortune for your Disaster and Kevin Prufer’s strange narratives and Matt Rasmussen’s Black Aperture–they all live in the real world, and look openly at the cruelty that masculinity expects of individuals and systems, and posit tenderness and vulnerability as a response (in varying degrees of out-loudness). I like this idea of assembling an ad hoc canon of re-envisioning masculinity poetics. I’m sure I’m going to come up with five more poets and books once I finish this answer, too.

Because you’re right–we’ve all got those friends whom we rode shotgun with, who inherited and in their own way modified or continued to develop these regressive primitive codes of dude-ness, which, in one of your poems titled “Love Notes”, you note is to fail but “keep trying in the customs of dudes.” This idea of persistence, wearing away, eroding any barrier–it’s its own kind of colonial impulse. That my need is more important than your resistance, that it will outlast it. It’s so valuable that these are questions you’re working with–what is consent, not just interpersonally, but also in poems. Who gets to tell whose story and how? It makes me think of Edouard Glissant’s contention that people (especially colonized peoples) are allowed their obscurity and that some things–some works, some feelings, some thoughts–aren’t and shouldn’t be available for translation. Just because you want something doesn’t mean you should have it. Just because the mountain is there doesn’t mean you get to climb it. I’m thinking of the Indian government protecting the area around Nanda Devi (second highest mountain in the nation) for safety but also religious reasons. It seems to me that we could all stand to learn to take no for an answer more, on every level.

But one of the other things in your work that I think is really important in your work is how it demonstrates alternative methodologies of writing, especially regarding your collaborations. You’re a preternatural collaborator, with artists, the historical record, your own past, the music of others. It’s great in so many ways, but a lot because it’s you showing us, your readers, things you think are great. It’s a kindness and like, a community service, to enrich so many people’s understandings of what different creative expressions are out there, and how they intersect with each other and poetry and life and so on. How do you approach collaborations? Or, how do you figure out with your collaborators how to work together?

AM: Thank you for putting collaboration in such generous terms. I feel exceptional sometimes because I have exceptional friends. They all have such out-of-this-world perspectives and talents. I’m constantly learning from them. My most recent collaborations were with artists Dario Robleto, Kevin Neireiter, and Nicholas Galanin. Completely different makers with completely different political and aesthetic agendas, but they’re all part of my community of inspirations.

We talk about community in poetry a lot because it’s so important to surviving as humans and artists. Maybe even more now after being so physically isolated during the pandemic. But I’ve been thinking about how community—connections, support, social nets, whatever it means for the individual—is one of the first things that gets fractured by capitalism and its duplicitous institutions. What better way to keep everyone from building than to encourage competition for crusts? Scarcity can either enable or completely dismantle community if the community isn’t ready for what’s about to happen. And there is a genuine scarcity of resources for poets (and all artists, really), too, so we have to be mindful and we have to be generous. Not in the sense of being effusive with each other on social media, though that is welcome. But in a more three-dimensional sense—sharing tangible and nontangible resources without fear.

I’ve been the recipient of this kind of generosity throughout my career and I try as best as I can to give that back in whatever ways are available. When I was Poet Laureate of Indiana, I ran workshops at the Center for Black Literature and Culture called “Poetry for Indy.” I modeled them after June Jordan and Etheridge Knight’s Poetry for the People workshops. I tried to create a writing space in downtown Indianapolis for people who didn’t necessarily have access to a writing community. I thought it would just be neighborhood poets, but poets started showing up from Evansville and Muncie and Ft. Wayne because they needed a space that would honor their voices. I’d planned on continuing them after my time as IPL was over, but the pandemic paused those plans.

I know you were in Houston (where my friend Dario Robleto has a studio—shout out to Kerry Inman and the Inman Gallery who helped me get the art for both Map to the Stars and Somebody Else Sold the World!) with all of the beautiful writers and visual artists down there, so I wonder how it’s been for you, leaving a space of intense connectivity for a more isolated writing life? Has your idea of what community is or is for changed in your new space with your beautiful new role as a father?

That went pretty far away from collaboration, but in my mind, collaboration is community. Back when I was finishing Map to the Stars, I realized that I’d pretty much answered all of the questions I had poetically. The place I was in my personal and professional lives, the geographic and psychic space I was moving through were no longer spaces of inquiry. They were monochromatic and imperative. The only way I could find my way out was through linking with artists whose work inspired me. I imagined—and it turned out to be true—that if I could spend some time working in other artistic mediums it would force me to think of poetics differently.

The only way I could find my way out was through linking with artists whose work inspired me. I imagined—and it turned out to be true—that if I could spend some time working in other artistic mediums it would force me to think of poetics differently.

Working with Dario, Kevin, Nicholas, and also Youssef Daoudi (who is the artist I’m making a graphic novel with) allowed me to think in series of connecting visual images instead of series of sounds like I usually do in a poem. Music has always been the center of the poetry continuum for me. After collaborating with visual artists, I’m now imagining images as a corollary driver of the poems. Yusef Komunyakaa is probably my favorite poet generally but also for his ability to move a poem with both image and sound. “You and I Are Disappearing” and “Venus’s Flytraps” are immaculate in this way. Anything from Magic City or Dien Cai Dau really. The poems in SESTW are nowhere near as potent imagistically as Yusef’s, but I see myself toddling in his direction.

One more thing about collaboration: I was very lucky because I worked with artists who are my friends, in addition to inspirations. The collective agenda for each of the projects was simply to make the most incredible art we could. The ego was centered in the success of our shared art, rather than ourselves. That’s important because when we’re out here writing or making by ourselves ego is vital. It takes a particular kind of hubris to want to create art, given how much of it involves failure, so we have to believe this work matters. But that ego can also get in the way when other artists are involved. I can imagine another version of collaboration where there would be all kinds of drama because the artistic imperatives don’t line up.

CB: What you’re saying about ego, and how much we need it in the act of writing, reminds me of something I saw Nathalie Léger. She was talking about the hubris you’re talking about–the almost heroic effort it takes to reach a velocity strong enough to escape the gravity of those feelings. You know, the ones that say “this doesn’t matter” and “who cares,” those feelings of pettiness or that it feels petty. I think that’s really important to acknowledge, not to mention practice (and is a thing I have trouble getting past–this worry that my life as subject is too egocentric and self-aggrandizing/dramatizing to warrant anyone else’s attention). At the same time, though, what you’re saying about community and collaborative work, and how it shifts the location of ego in the process, so that it’s centered on the work itself and not the self, is such an important counterweight. To live in one extreme too long is to go full narcissist; in another, shapeless. For both of these, though, doing work that is one’s own, and doing work that is the collective’s, it feels to me that community is really essential.

I think this has become clearer to me as I’ve drifted further away from the community I had in Houston, which you rightfully note is vibrant, stimulating, and a little scruffy. I loved it there, and the people I got to spend time with in that city. Being away from it has given me perspective on just what I had, and how hard it is to get that. But with distance, and the recent thoughts and words of people like Matthew Salesses, Aditi Machado, Hanif Abdurraqib, and Éireann Lorsung, community is a thing that both sustains and differentiates you. And I think this sustenance and differentiation is really important for writing–as an individual, in community (people you chat about poems and life with over beers or ice cream) you get support and perspective that helps you feel like an interesting and intelligent person/creator as well as an individuated person. As a community, you’ve got people to work with, to help you consider and work with different perspectives, people who push you, in your own work but in your work together, too, to do more than you would otherwise. It’s kind of like the weird miracle of pressure and tension that allows a meniscus to form, the water gripping itself, the air resisting but also accommodating it.

Often I go to community for the same reason I go to poems: for perspective. To help me see the human side to a mass event, or to see the scope and history a small feeling can be traced up to. To challenge my understanding. Having poems (and essays and fiction) has helped me maintain that in the absence of direct human community, but you can’t replace the glee of a friend’s cackle or the opportunity to learn what you mean when you share an opinion on a line break. I can only imagine the opportunities for this kind of interchange that your workshops in Indy helped create–those sound so important, not to mention amazing! Here’s hoping the pandemic is under control soon and you can get them spread out among the Hoosiers.

At this point, I think I’ve just got one question left (though I wouldn’t mind if this convo just unspooled over the next couple months). We’ve talked about so much–music, parenthood, complicity, desire and consent in life and poems, community and collaboration. I’ve really appreciated the chance to see inside your process, your poetic values and aspirations, and what you hope Somebody Else Sold the World can tackle. I wonder if we could end by thinking not just about the poet, the work, the community, but poetry with a capital P, and what it can do. I really love what you say about it being “a megaphone at a protest and not a gun”–what amplifies but not what acts or does. What can, or what should, it do, and does that goal or purpose differ during times of crisis, as we’ve seen of late, or is it a question of intensity/degree?

AM: It’s been so great talking with you about all of this, Conor. I’m wishing you and your gorgeous book the most massive success possible and I’m excited we get to read together on the 15th!

It’s wild because I just got my author copies of Somebody Else Sold the World and I’ve been slowly inscribing them for my close friends and family. I have a nephew in the Air Force and I’m so proud of who he is and who he’s becoming. When he was younger, my sister would drag him to my poetry readings constantly. Somewhere along the way, he stopped fighting about it and wanting to be there on his own. He doesn’t write poetry. I don’t think he reads it much, either. But there is something about the atmosphere poetry creates that he enjoys.

I don’t know how he will react to this new book because as I told him in my note, the book is mostly full of uncle music. But I know he’ll respond in some way because he’s aware and open to possibilities. Poetry accesses some secret need in all of us and what it gives us might change depending on the world around us, but it all starts with poetic need. This pandemic has been awful in every conceivable way for our emotional and psychic wellbeing. For our art, too. I managed to write this book, mainly because I was clinging to poetry for survival.

Poetry accesses some secret need in all of us and what it gives us might change depending on the world around us, but it all starts with poetic need.

One good thing that came out of this time—and this speaks to what poetry can do—is a different idea for what poetry fellowship might look like. Those first couple of months were bleak and disconnected. Somewhere in there, people figured out how to use Zoom for readings and that changed everything. It gave people access to work they never had access to before because of geography, resources, availability, or time.

One of the most stunning and previously impossible events happened in June 2020 as part of Patricia Smith’s 65th birthday celebration: 65 poets each reading a poem in her honor, split over two nights. Patricia is one of my favorite poetry people, for her stunning poetry and for all of the work she does in the literary community, so it’s no surprise we all wanted to celebrate her. The event itself was a historic, literary occurrence that wouldn’t have been possible without Zoom. All of these dazzling, grateful poets “together” from all over the world reading poems to and for Patricia. I want to list names, but there were so many heroes that it would be disrespectful to choose who to name. But I think part of it is posted on YouTube (the second part, which you can find here).

Now I’m thinking about something that the novelist Ben Okri said about poetry. It’s cleaner than any definition I’ve come up with, so maybe I’ll just lean on his language. The quote looks long, but it’s only two sentences:

The poet needs to be up at night, when the world sleeps; needs to be up at dawn, before the world wakes; needs to dwell in odd corners where Tao is said to reside; needs to exist in dark places, where spiders forge their webs in silence; near the gutters, where the underside of our dreams fester. Poets need to live where others don’t care to look, and they need to do this because if they don’t they can’t sing to us of all the secret and public domains of our lives.

I love this job description. Okri’s talking about The Poet, but in truth the poet and poetry are symbiotic and make The Poet. They are both amplifier, enabler, conduit, stylist, wishing well, and a mouthless trumpet for each other. They each make possibility possible for the other.

Rajiv Mohabir: FROM “SWAGGERMAN, FLYMOUTH” A DEVIANT TRANSLATION

Introduction by Rajiv Mohabir:

The poems that follow are from a forthcoming manuscript. These poems are a type of translation of a Caribbean chutney song called “Na Manu” by the Surnamese singer Bidjwanti Chaitoe Rekhan in the early 1960s.

The song “Na Manoo Na Manoo Re” from the 1961 Bollywood film Gunga Jamuna in which Lata Mangeshkar sings a song of similar lyrics may have been an inspiration to the Sarnami Hindustani song of Bidjwanti Chaitoe Rekhan.

Still, adding more layers and complications, is this song, remade by Babla and Kanchan– a duo from India who took Caribbean songs and remade them for worldwide distribution in the 1980s– that was very popular in my family and the community of Guyanese and Caribbean Indians that we interreacted with in Orlando, New York City, and Toronto, so my move to translate them is one that is intimate given my own linguistic history of erasure and reclamation. This is the version that I grew up dancing to, knowing it intimately in the twisting of my body in feral dance.

What is remarkable about each remake and each rebranding is the change in lyrics and instrumentation, translated each time to fit the contexts of the viewers/singers/dancers/audience. To start with the Surinamese version, the regularization in Rekhan’s lyrics allows for a predictable structure that is easily replicable, though it maintains the play and irony of the original. I keep the play and irony of the original in mind as I work through the various pieces in this section of the translation process I am presenting here.

The process that I use to translate this song I’m calling “deviant:” these are deviant translations. I want to destabilize language and the ideas around final realization and “arrival”, in order to resist stasis and provide space for all of the queer slippages of language and their worldviews in their very particular speech communities. When I was younger these songs in Hindustani would be translated into a Creole iteration with a different poetic orientation. The English interpretations were up to me. All of the poems are retranslations of retranslations of retranslations in and out of Guyanese Hindustani, Guyanese Creole, and English. In this way I envision each incarnation as a possible emanation from the text as even the idea of primacy and the original are dubious. I approach each iteration with a different idea of what I want to communicate: what affective dimension is available in the language that has similar resonances throughout while not always being literal. What are the affective hauntings of these lyrics, languages, and musics? This is the central question driving my experiment.

I’m also obsessed with Creole and Bhojpuri indeterminacies in English and the ways these languages use grief, humor, and joy in differing ways. Using Guyanese Bhojpuri, English, and Guyanese Creole, the deviant translation is nonbinary and ever migrating. (In live performances of these songs, performers sing as the spirit moves them with lexical fluidity an incarnation of their own creative magic). What results are translations that are not translations as such in that there is no resting place but rather motion with the deviant driving the multiple crossings.

From “Swaggerman, Fly-mouth” A Deviant Translation

Swaggerman, fly-mouth

what is true?

I take in the raven moon’s glow

so when you deny me

I’m still opalescent.

Why veil this shine

for a liar’s night, a mind

wipe serum?

My churas are not shackles—

It’s morning and I’m gilded.

*

Things Not to Forget in the Morning (Liar Though You Be)

moonlight moonlit night full moon light

my veil with kinaras of gold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

golddupattagold

my silver bera

*

a song from laborer to recruiter is that why it is so sonorous and resonantly all these years later summoning the ghosts of tide and bond how even as the language receded from us like a tide coolies couldn’t release still can’t let fly this story or rather it possessed us in the dance halls as soca chutney a music salve for the pain of forgetting for getting into the boats and we are haunted by the memory of a promise of return but it wasn’t about the physical return but a return to wholeness-as-India that our masters and owners reneged on denying generations any passage not rum-doused and sun-scorched is this why we dance so fiercely in the moonlight is this

*

What part of me is memory?

The skin and muscle,

neuron and fat—?

Don’t believe in god.

It’s a mean lie to lay you down

to strip you of cloth and gem.

You are not headed any place

but into the ocean as cremains

and pearls of bones

not quite machine smashed.

Did you forget? Is it beautiful

this morning where you think you are?

*

चूड़ा बीढा काढ़ा

काँगन बाँगल जिंगल

चान्दी की चान्दनी जइसन

दुपट्टा चुनरी ओढ़नी

निक़ाब परदा रूमाल

बदन की बदनिया जइसन

*

Look. Wha’ me know me go tell yuh

De man come

an’ tief all me ting dem

‘E come cana me

an’ talk suh lie-lie talk

an’ me been haunted

fe lie dung

whe’ ‘e put de ordhni

But wha’ matti hable see a night?

Come daylight

dopahariya

‘e na remembah

me na me bangle,

how de moon a shine,

O gas—

how de moon been a shine

*

Sugar floss melts in dew

forgets its thread’s any spun yarn

So what thing is moonlight

who deposits amnesia

for even a woven veil

to dissolve from your memory

despite my ornaments

exquisite and golden forged

all lost in the ephemeral jewels

globes of hundreds of tiny suns

bending grass leaves

into pranam which is both

greeting and leave taking

- Published in home, Monthly, Translation

INTERVIEW WITH K-Ming Chang

I first read K-Ming Chang’s writing in 2018, back when I was Fiction Editor of Nashville Review. Her story, “Meals for Mourners/兄弟”, captured my attention with its embodied, elemental language and stirring portrait of family life. Since that time, Chang has written a novel, a chapbook, and a story collection, among other projects. Currently, she is a Kundiman fellow. Her story, “Excerpt from the History of Literacy”, was published by Four Way Review in November 2020. While Chang’s characters bite, use meat grinders as weapons, and store their toes in a tin, Chang herself is generous of spirit, prone to doling out affirmations. During an unseasonably warm day in early spring, we talked about the craft of writing, giant snails, and the magic of making things possible.

-Elena Britos

FWR: Today I thought we could talk about your writing through a craft lens. Craft means different things to different people. To start, writer Matthew Salesses says in his recent book, Craft in the Real World, that “Craft is a set of expectations. Expectations are not universal; they are standardized. But expectations are not a bad thing.” What expectations do you feel you must meet in your writing, and whose expectations are they?

(Chang holds up her own copy of the book excitedly)

KMC: Maybe this is more what expectations I don’t meet, but I never want to explain things [to the reader] I wouldn’t explain to myself. If I were the reader and I wouldn’t need an explanation, then [as the writer,] I’m not giving one, even when I know it could make the reading more difficult for someone else. I write for myself first and foremost. I always use myself as a compass. If I am surprised or delighted by something or laugh at something or understand something, I allow that to be the compass. If I think too much about how a stranger will read it, I lose all sense of how I want the work to be.

FWR: So you’re meeting your own expectations when you write?

KMC: Yes. My expectations for myself are harsh, and I can be self-deprecating toward my own work. So, what I try to do is distance myself from [my work] as much as possible. I try not to think about how this is something I’ve spent a lot of time on and hate. I try to give myself time, a couple months or longer, and come back to the page to experience it as a reader. I look for a sense of surprise, always. I want to think, “Wait, I don’t remember writing this! I didn’t expect it to end there!” If I am not surprised, I know it’s not ready yet.

If I am not surprised, I know it’s not ready yet

FWR: How do you shock yourself when you are the one creating the surprise?

KMC: It does happen! When it goes well, the work ends up really far from where I started. It’s like a game of telephone from the first sentence—it mutates so much. Sometimes the surprise is even just a metaphor, and that can be enough.

FWR: Right now, you edit The Offing’s Micro section, which the journal files under its Cross Genre vertical. When I think of your writing as a body, “cross genre” is kind of the perfect category-defying category for it. It’s like having a non-container. Yet, no matter what form your writing takes, I feel I would recognize a K-Ming Chang piece anywhere. Part of the reason for this is your use of language on a line level. How would you describe your style?

KMC: I love this idea of a non-container! I think my style is very language driven, the idea of letting language lead me rather than logic. This sometimes results in a lot of derailing in my work—like, wow that sounded really interesting, but what does it mean? I find that’s where I have to reign myself in. I am very interested in lineages and mythmaking, creation and destruction, the elemental things that are common in mythical worlds. My style is hard for me to describe because I feel I am always trying to break out of my own style. When I write poetry, I am always trying to break out of my own poetic voice, and when I write prose, I feel very resistant to prose forms and sentences. So, it’s a constant wrestling.

I think my style is very language driven, the idea of letting language lead me rather than logic

FWR: I am always amazed by your ability to work fluidly across genres and forms. You write poetry, short stories, novels, micro fiction, and beyond. You have a poetry chapbook coming out from Bull City Press called Bone House. You also have a forthcoming story collection from One World called Gods of Want. When you sit down to write, do you have the intention to create, say, a short story from the outset? Or do you first have an idea for what your narrative is about, and then select its formal (non-)container?

KMC: I used to think it was a profound process, but it’s really like having a loose thread on your sweater that you yank. Usually, I start with a first sentence or even a few words. And then I pull on it and pull on it and let it expand. Usually what ends up happening is that whatever I think I am writing ends up as a giant block of text. When I think about what kind of narrative it will become—if it is a narrative—that is part of the revision process. When I am in the process of writing and producing, I really have no concept of “is this fiction, is this autobiographical, is this an essay, is this a poem?” That’s a lens for later.

FWR: That shows in your work. It feels like the language almost comes first and then the story blooms in this really interesting, organic way. What was it like writing Bestiary using this process?

KMC: I always joke that I tricked myself into writing it. When I was writing it, I wasn’t thinking, “Oh, this is a novel. This is a full manuscript or project.” I wasn’t thinking anything. I was allowing it to be fragmented, almost like a series of essays, where each section had its own completed arc (which I later unraveled). I wanted to play on the page and have the scope be a bit smaller while I was writing. If I thought, “What is the through-line? What is the plot?” it would have been mentally strenuous, stressful, and scary for me. It was a mind trick. Then later, I unstitched it all and rewrote it.

FWR: When I read Bestiary, I was struck by the density of figurative language and how you use proverbs to explain the world. For example, “the moon wasn’t whitened in a day” and “burial is a beginning: To grow anything you must first dig a grave for its seed.” For me, these aphorisms are a kind of hand off into the myth and magic in your stories. You explain the world through the earth, through the body, through transformation. Your characters do not only feel that they have sandstorms in their bellies when they are sick—they literally have sandstorms in their bellies. Can you talk about the connection between language and transformation in your stories?

KMC: Wow that is so beautiful and profound! I think transformation is the perfect word. In a lot of ways, it is like casting a spell with language. Through metaphor, you turn something into something else. In the language, that is the reality. I had a teacher named Rattawut Lapcharoensap who wrote a story collection called Sightseeing. He told me that writing makes something possible that wasn’t possible before. I love that definition of writing—to make something possible. It is also very literal. You take a blank page and put words on it that weren’t there before. If you think about it that way, it isn’t so profound, but there is something magical about it to me. Regarding proverb and myth, I love that language can be embodied. Language isn’t just a passive tool to render something. The poet Natalie Diaz once gave a talk at my school, and she said in the alphabet, the letter A came from the skull of an animal, and that’s the etymology of the letter A.

FWR: I feel like you wrote that! Speaking of real histories embodied in language, many of your stories are metafictional. In your short story “Excerpt from the History of Literacy,” your novel Bestiary, and your forthcoming chapbook Bone House, you use myths, wives’ tales, epistolary, oral storytelling, and Wuthering Heights to inform your narratives. In your mind, what is the role of the metafiction for the plot at hand? How do other stories inform what is happening in your own work?

KMC: I love that you asked about metafiction because I’ve actually been thinking about this. It’s interesting because when people think metafiction, they think postmodern. They think that it’s a very recent thing to have moments of meta in fiction. Chinese literature is extremely metafictional. The beginnings of chapters will say, “In this chapter, here’s what you’re going to learn.” And then at the end of the chapter they’ll say, “to find out the end of this conflict, read on to the next chapter.” In a lot of translated Chinese fiction that I know and love, there’s this sense of artifice. I am constructing something for you, so read on to the next chapter, the next scaffolding. It shows you the performance of the fiction, which I love so dearly. It’s ancient, not experimental or new or strange—maybe it is to Western audiences. Regarding plot, I think there’s something very playful about reminding the reader of the fiction. It kind of breaks the expectation of realism, which opens up the possibilities—this is all a construct anyway, so why can’t you give birth to a goose? Why can’t you fly?

Regarding plot, I think there’s something very playful about reminding the reader of the fiction. It kind of breaks the expectation of realism, which opens up the possibilities—this is all a construct anyway, so why can’t you give birth to a goose? Why can’t you fly?

FWR: Earlier, you mentioned you write to fulfill your own expectations. In her lecture titled “That Crafty Feeling”, Zadie Smith says that critics and academics tend to explain the craft of writing (or, expectations) only once a text has been written—that is, after the fact of making. She says that “craft” is almost retrospective. It doesn’t really tell a writer how to go about writing, say, a novel. Does this resonate with you?

KMC: I completely agree! There are so many times where I’ve only been able to articulate my intentions, or what tools I’ve used to articulate those intentions, long after I’ve written the thing. Most of the time I don’t even know my own motivations, much less my own expectations, for writing a particular piece. I think that’s part of the joy and mystery of the experience – if I clearly know my own expectations and how I’m going to fulfill them, it tends to fizzle out quickly. There’s something about being a perpetual beginner, or at least feeling like one, that makes writing possible for me.

FWR: Have there been times when you’ve been given craft advice you refused to heed? What writerly hills have you died on? You’ve been lovely to work with from an editorial standpoint, but I wonder if there are times you feel the need to put your foot down.

KMC: I love getting edits and feedback because I’m constantly lost in the woods. I’m always asking what to cut—I welcome it! But I think I struggle with conventions of storytelling that we get told as writers. We internalize things like, “Make sure the narrator is driving the story and have an active narrator.” I’m really curious about stories that have characters who are caught in the eye of a storm—who are not necessarily driving the story, but are in circumstances where the world is what is moving them, because of status and who they are! This idea of an “I” narrator who creates conflict and action is a very particular way of seeing yourself in relation to the world that I don’t think my narrators have the privilege to experience. I have also been told, “Every word is necessary”—to have an economy of language. There’s an interview with Jenny Zhang in the Asian American Writers Workshop where she says, “I don’t want to be economical. I want to be wasteful with language.” I loved it so much I wrote it down. I fight against this utilitarian idea. Write toward the delight of sounds and words. Why follow this capitalist directive in the way that we write? I think breaking out of that is really important.

I fight against this utilitarian idea. Write toward the delight of sounds and words. Why follow this capitalist directive in the way that we write? I think breaking out of that is really important.

FWR: I like the idea of being wasteful with language. I think you could also see it as being generous with language.

KMC: Yes.