FIRE AND JEWEL by Sydney Lea

Eighty-foot hemlock, spruce, fir, and pine–

They kept lifting off their stumps like so many rockets,

Smoke-trails and all. And I

Beheld the fire cross-lake from where I drifted.

I’d been pounding the water for bass when my eyes were lifted.

Fifty years later, I still recall my thoughts,

And how I thought that to think them was more than odd:

I felt gladness at having the faculties to notice

The hill’s spectacular, orange heat as it flared

To white with each explosion,

Then the whole of the conflagration bending toward earth,

A horizontal wall, a monolith,

That somehow tore downhill in a sudden blast

Of wind. It was gorgeous. Several hours would pass

Before I knew the flames had set Bo Tyson

Flying down Blake Cove Mountain on his grapple skidder

And into the lake by Stearns Island.

He had to take the loss. It was that or burn.

Donald Peavey, wielding an axe in his turn

With the makeshift crew, collapsed from labor and heat.

Mason the storekeeper dragged him away by his feet.

I knew Don, sadly, only a few more years.

He and Bo and Mason: all good honest men.

I can’t account for my dreams,

But last night I dreamed I watched that fire again.

Miles above, in what seemed pure quiet, serene,

The same jetliner crossed as did years ago,

The same scent rose– torched needles, caustic smoke,

The same diabolic roar coming on as I rocked

In the same canoe, the waves still slapping its hull.

In an hour five decades back

The length of that ridgeline turned as black as onyx.

My dear wife’s latest birthday will soon be upon us.

Is that why the dream passed smoothly into the next one?

I saw, precisely, a beautiful onyx pendant,

Hung on a chain from that comely woman’s neck.

I’d never dreamed such a lover as that rough ridge blackened,

Wouldn’t meet her for years and years. Nonetheless,

I drove to a jewelry shop upriver this morning,

Three hundred miles to the west of Blake Cove Mountain.

On buying the necklace, I felt some fire in my being,

Mild version of one that one ancient June got kindling,

And underground, for a long time after, kept burning.

- Published in Issue 8

HAPTIC PERCEPTION by Athena Kildegaard

The nurse wears blue gloves.

Her stool turns on four black wheels.

A shot is the first course.

I shouldn’t have picked up the bat,

wounded, vulnerable in the street.

The nurse wears blue gloves.

The violence of life, red in tooth

and black in death. Silence of the syringe.

A shot is the second course.

Bats deserve to live, who could

deny it, though we fear them (I should).

The nurse wears blue gloves

and tells me to call in case

of headaches, fever, malaise.

A shot is the third course.

We laugh as I turn down the hall.

I know she doubts my sanity,

this nurse who wears blue gloves.

It’s too soon for mosquitoes.

My children are grown and moved away.

The nurse wears blue gloves.

A shot is the fourth course.

- Published in Issue 8

THE DAY AFTER A GIRL SPROUTED IN THE FLOWERBED by Kathleen McGookey

Mother yanked her out. I filled my watering can with milk.

In the hollow, we could barely see my bedroom’s yellow

eye. I patted dirt over her bloody roots and stood her up

again. When I stroked her cheek, she turned toward me and

opened her mouth. And when she sang, she sang about a

sparrow and a leaf. And when she yawned, I saw baby

teeth. Would she grow? Would she live? She needed a

collar of feathers, a pillow of violets. A birchbark suit. A

firefly lantern outside a small house made of stones polished

in the creek. Mother’s shadow opened my window and

called. We didn’t have long. The tree frogs’ silver chorus

rose in waves as I ran back to my house. I could still hear

the girl’s faint sparrow song. Maybe she was calling me.

- Published in Issue 8

MARIA OF THE ROTTING FACE by Emily Jaeger

llena eres de gracia

crouched on a stump,

feet dug into the red dust,

you peel the mandioca

they feed you each day

to ten white blades.

Bless this home

bendita tú eres.

Your children,

their hundred chickens,

fourteen pigs, six cows,

three hives—

you counted them

before words turned

to blue gum

and you buried them

with your teeth

in the corner of the low hut

they built you

between the rows

of pregnant squash.

Bendito es el fruto.

They place your meal

on the fire

and you consider

the flame: a stranger

carrying a tiger-

lily

and you have

forgotten

what it all

means.

Your rosary of flies

memorizing

the days since

ahora y en la hora

they called you mother.

- Published in Issue 8

FWR Monthly: September 2015

Meditation frequently asks its practitioners to ground themselves in their bodies through a series of structured “noticings.” You are gently urged to press yourself into your chair, press your feet into the floor, press your fingertips together, press your lungs out into their little cage of ribs.

It is easiest, it turns out, to notice your body when it meets with a measure of resistance. The floor is a fact your feet cannot change. To live in a body, we are told and retold, is to forget about this all the time.

When I solicited poems for this issue, I asked for work that “enacts or inscribes the feminine in fresh, unusual, or surprising ways.” Noting that gender is both inscribed upon the body and enacted by the body, I wanted to see how gender could visit the text, or the site of inscription. It is, in fact, near-impossible for many of us to forget about our bodies. This is not a failure to live within them, but a ricochet from resistance to resistance, reminder to reminder – “You do not inhabit this body. To the world’s eyes you are this body. Here is what that means.”

I’m delighted by the poems in this issue, in no small way because they make the original phrasing of my solicitation seem deeply small and beside the point. They embrace the mystic and the vulgar. They are funny, heartbroken, and kind. They dig deep for inner voice and reassemble the voices around them in a gorgeous echolalia. With plums. And hoofprints. And Kim Kardashian. I hope you like them.

Kate DeBolt

Assistant Poetry Editor

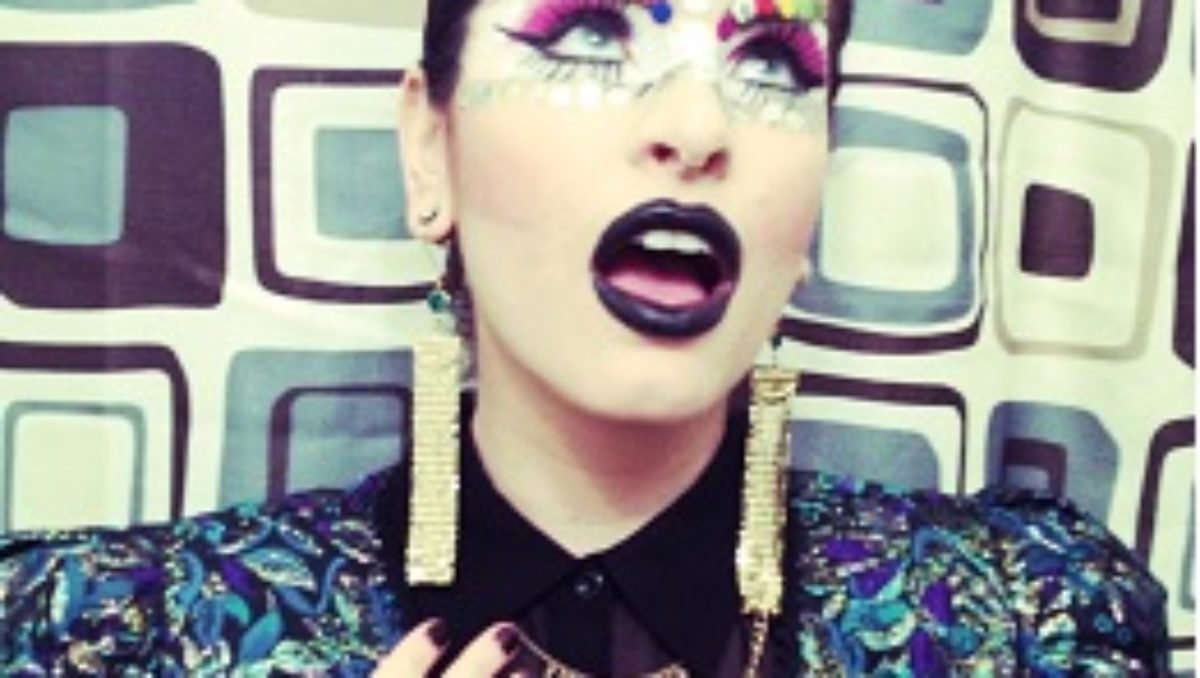

DRAG NOTES – FROM A CONVERSATION WITH KINGA

by Justin Engles

TWO POEMS

by Danielle Mitchell

THREE POEMS

by Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

PRAYER TO ST. MARTHA

by Leah Silvieus

Artwork by Lexi Braun

- Published in home, Monthly, Uncategorized

DRAG NOTES – FROM A CONVERSATION WITH KINGA by Justin Engles

Davenport, Iowa. If you can believe it. Of all the dive bars in all the world, that’s where I

saw my first drag show. I was 19. And there was this queen there —Ginger Snaps.

She was a pointer-sister. She really served up the fantasy.

I said to myself,

that looks like a lot of fucking fun.

It took seven years until I saw her in the mirror.

She’s an instrument I made.

I become her

when I put on her eyelashes.

My body language changes,

my whole posture changes,

an action, a movement, a gesture, a pose.

I don’t want to become a woman. I want to be

a catalyst. Write that down.

You asked earlier, where desire figures for the crowd.

They all want to be changed—their mood,

their night, their rut. Call it escape, or release, the transaction is simple:

when I serve realness, I deliver what is true of a fantasy.

And if you ask me that’s the dregs of any request, whether it’s for a joke or a blowjob—

we don’t want the fantasy exactly, we want that little act of mercy that assures us the fantasy

is real.

- Published in Series

PRAYER TO ST. MARTHA by Leah Silvieus

Late August the galley blooms

fruit flies, smoke-winged & garnet-eyed, circling the soft caves

of over-sweet summer fruit: pear & blueberry, clingstone

peach. Each night I pray resurrection

but am deceived. Faith is not feast

but desire, not beauty of the table but what drags us starving

there – what was buried inside

the sweetness, inside

the plum’s bruised heart: larvae, pearling. Saint dear

of my difficult hunger:

cloy me

mote me

rise me up

- Published in Series

THREE POEMS by Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

ISADORE—THERE IS A DOOR SOMEWHERE

paused in the breath of a thousand

horses where we wait for light

to catch our arms, bodies into nets,

golden sea flecked with ravens’

wings. Dear, I want to fly as quick as I can

into a canyon, leap hard into your

eyelids—how they never formed

enough to open—I will wait, still.

In this dream we circle you

in prayer and open any body willing

to be demolished in your name.

FRANCINE IMAGINES A JURY OF TWELVE WOMEN AT HER FUNERAL

Francine tastes the first words at sunrise, splits the verdict between them: her accuser at one end of the table, her Father at the other. I have guns of forgiveness for both of them, she writes. To Francine, forgiveness is a weapon for the last day she will be alive. To slice the throats of my accusers with kindness, a warm waterlike love washing us slick, she writes, in artichoke blood.

HOW BEGINNINGS ARE MADE

How the hay hobbled on

the mule-backs toward ice

caps covered with the unborn

on blankets beneath the one

star, beating-hearth, mother,

her snow watch, warming—

how before-children wanted

to see the one who loved

their bodies until she broke

herself open—how, off course,

mules moved holy hay, making

prints, perfect O’s, hooves

above the tree-line, to feed

the birth-sick their sight, source.

- Published in Series

TWO POEMS by Danielle Mitchell

GOOGLE CENTO

Enter: kim kardashian body

If you know nothing else about Kim Kardashian,

you know that she is an actual woman, a physical body:

5 feet 2 inches, 130 pounds, 38-26-42, 34D

Kim Kardashian is queen of her self-made kingdom

Kim Kardashian’s Entire Body Is Naked in These Paper Photos

Kim Kardashian’s Body Evolution

Is Kim Kardashian ashamed of her body? | Watch the video

The Lazy Girl’s Guide to Waist Training Like Kim

and her already infamous body-ody-ody

Kim Kardashian has basically made a career

out of her bodacious curves—

Why your post-baby body isn’t like Kim Kardashian’s

If you believe in God, you might be one of those people

who thinks that Kim Kardashian’s body is evidence

of his existence

Kim Kardashian Reveals She Was 20 Pounds Thinner in 2009

I got so huge & it felt like someone had taken over my body.

Amazon.com: Kim Kardashian Signature Body Mist for Women

Honeysuckle, Jacaranda Wood, Vanilla, Tonka Bean, Orange Blossom, Musk

Kim Kardashian Reckons Her Pregnancy

Forget the Ass, Kim Kardashian Goes Full Frontal

Opinion | Kim Kardashian, there’s another way

And Now, Let’s Let Tina Fey Have the Last Word on Kim Kardashian

Kim Kardashian Didn’t Always Love Her Body

Kim Kardashian Says She Used to Pray

BEDROOM INTERVIEW

“Hurry. What matters is to be inside the prayer of your body.”

Sandra Cisneros

The story wants to devour a girl. Her hands,

two groping accidents that forget

to cover her face. All will recognize

her face, but for now here is the room

she grew up in—

here are her favorite books. Open the blinds.

The sun will strip her body apart. Unbuckle

the spine from its latches, legs

wide, wider & asking what is holy?

So the camera goes & the girl knows no one

will ever love her again. The breasts make

a seam with the body, which casts

an unfamiliar light. It isn’t vanity

that eats her alive & the room

echoes that tell-tale. She wants it

says the forsythia on the blanket, reaching their bright

yellow tongues toward her knees.

We’re losing her say the dresses. I can’t watch, the mirror.

It’s cold in here her heart says as she switches

positions on the mattress which cries

she used to use this bed for sleep.

- Published in Series

excerpt from FIEBRE TROPICAL by Juliana Delgado Lopera

I met the Pastores at Iglesia Cristiana Jesucristo Redentor two days after we landed. To my surprise the church was a room, a room, inside The Hyatt a few blocks from our house. Was I the only one appalled by its lack of holiness? Did Mami wave her estrato like a flag of entitlement and walk out? She hugged and kissed and called this lady hermana and that señor hermano like this was totally her salsa and I was exaggerating. Painful to watch. Mami sensing my discomfort mentioned a youth group, people my age learning about Dios. Clearly this was all a mistake.

When we got there three fat women in matching navy suits ran to greet us, introducing themselves as Ujieres, mi niña, Dios te bendiga. A low cemented arch with three palm trees to each side where a sign for the South Florida Beauty Convention hanged on the side. And then: the room that pretended to be a church. Talk about being colonized by the wrong people, the wise Spanish understood it took Gothic fear to believe and follow Dios. For starters the churches in Bogotá were old, like centuries old, gothic, tall with vitrales, and colossal images of the Virgen de la Caridad, Virgen de Chiquinquirá, Virgen del Carmen, bleeding tears on the baby, the backdrop of the altar a nailed Jesús de Nazareth face contorted—did I mention homeboy also bled?—showing you he died for you, sinner. During the weekly school mass whenever I searched for spiritual or moral guidance the image of the bleeding, good-looking bearded son of God shook me into my senses: stop fake-kissing your Salserín posters Francisca, he died for you. And although my religious skepticism started at the age of 11 when I began falling asleep during mass, stealing my tías’ cigarettes and rubbing myself on the edge of the bed, the imposing thorn crown bleeding for all of us had created a fear so deep I found myself praying unconsciously after each said sin.

But enough of the past already. Mami always says you gotta look into the futuro, el pasado está enterrado, we sold it, buried it and bought new flowery bedspreads at Walmart instead. And now Iglesia Cristiana Jesucristo awaited with its baby blue walls, four rows of folding chairs and a passageway in the middle. A mustard yellow carpet that resembled Mami’s favorite blouse which tied in a perfect silk bow and hadn’t been worn since her farewell party at the insurance company. Bibles secured in armpits. Everyone blessing their hermano, declaring in the name of Jesús, gloria a Dios for Sutanito’s new job at Seven-Eleven, and beware of Satanás when your children curse at you.

Women kneeled at the center. Others painfully hummed songs as a young man began drumming beats, their faces obviously demanding attention because as everyone could clearly decipher from the tightness of their fists, the hermanas suffered.

They couldn’t be serious, but they were.

I remember the awkward embarrassment, an urge to tell everyone to please turn it down a notch. Amazed at the lack of shame in blasting Christian rock and singing to it while people watched—normal gringos peeked from time to time, entertained by the free Spanish spectacle happening right at their hotel. People are watching you, I wanted to say. But at that moment all they cared about was proving to each other who was Jesús’ #1 Fan, and to be honest it was a tough call. So instead of snapping I actually yearned for the mournful, silent quality of Catholic mass. The Ave Marías, the bells, the Latin phrases nobody understands, all of us girls in uniform passing notes during the evangelio. The imposing holiness of the priest, his robe—the Pastor wore black pants and a dark blue shirt that made him look more waiter than godly.

Mami explained the Christian logic of such circo to me later: you can praise el Señor anywhere, because He is everywhere and He is watching you, sinner. It’s about a direct relationship with Jesús and Dios, no intermediaries, no fake images to praise. What about La Virgen? Na-ha, no Virgen. Dios mío. Fifteen years lighting candles to the Virgen, waiting anxiously for rosaries to end, fifteen years with a Virgencita around my neck that protected me of all mal since my baptism. And now, suddenly, the Virgen and I faded into the background.

Mami introduced me to the Pastora inside an arch of blue balloons framing the stage. A sign—lead singer works at Kinko’s— covered half of the end wall with a rainbow reading ARCOIRIS DE AMOR. On the left two huge speakers. Big party speakers because this was a party para alabar a Cristo. A Jesús party. Someone whispered to me: Jesucristoooo.

La verga, I told Mami.

Grosera. Okey, here don’t be grosera.

Half of the people were thick women with hair done in highlights, fake red nails, kissing each other’s cheeks with tired eyes while some mumbled things in English with an air of superiority. Clarita! Como ha aprendido inglés, mire a la gringa. Children wailed, chanted. One of them colored a dove black, the bird breaking the lightning sky. Why black Marcelita? Aren’t you Jesús’ little princess? It should be baby blue. It should be white. Holy spirit is pure mi amor, a ver. Young girls in white sheer gowns shook tambourines, held hands, eyes shut letting out a siiiiiiiiiiiiiiiigh to the heavens. Above, the heavens, three colossal ceiling fans going whoosh whoosh whoosh and at the back table a man alone in headphones. I asked Mami and Mami asked tía Milagros and tía Milagros responded that it is the Biblical Translation Center, for the gringos. This is a real time translation Spanish to English with headphones. Oooooooh. See how good? Even the gringos come here. Tía Milagros pointed to a giant white man with tiny spectacles seated in the first row wearing headphones hunched over a bible. Mami was super excited about the church’s inclusivity. Of course Mami couldn’t stand the gamines outside of Catholic mass asking for money or Lucia’s close friend a moreno from Barranquilla, of course not. But gringos, she’s been super excited about. I pitied the yanqui man a little. Why in the world would a gringo come to this church? Don’t they have their own?

People jumped to touch me, asked all kinds of questions. Lady in yellow dress and with enormous cleavage (Marcela, later barred from stealing the diezmo), Mamita are you Myriam’s daughter? Xiomara mira, this is Myriam’s daughter. No way, you don’t look anything like her! I held you when you were this big.

This is exciting, I thought, very exciting. Is it different from what you had in mind? Is it different from The Promised Life? Is it different from the yellow-haired blue-eyed heaven of boys and girls in Saved by the Bell wanting to be your friends? Cachaco, please, I wouldn’t have conjured up this place in my head in a million gazillion years (and I grew up in Bogotá during the 90s).

You come with me to the youth group, nena.

Mami sat in the first row, next to the bald Pastor and his terrible mustache while Xiomara with her gelled curls escorted me to the room next door.

Xiomara’s infomercial voice made the walk a sort of limbo, stuck inside a television screen. Down the hallway men in shirts, gelled hair, smiling out of some sort of obligation, handing me their sweaty palms. Free embraces that I never asked for. Lots of arms around me chanting in unison Dios te bendiga! Dios te bendiga! Dios te bendiga! But I thought, I’ll meet some people there, right? I couldn’t imagine young people going there out of mere will and a light sense of hope let me breathe deeply one last time. And there taped in gold on top of a rainbow read: Jóvenes en Cristo.

Here’s a little something for you, mi reina: All these colombianos migrate out of their país de mierda to the Land of Freedom, in this case Miami, to better themselves, to flee the “violence” or whatever, seek peace, or, really, to brag they’re living in the freaking U.S of A and hello credit card, and hello cell phone and car I can’t afford, and hello hanging out in a room at the Hyatt with the same motherfuckers you ran from. Like, they couldn’t have done that in Bogotá? Barranquilla? Or Valledupar? My second reaction to the room-church was a terrible disappointment. This. Is. It? Whaaa? More on that later.

Now, what I saw behind that door had been inconceivable before (cachaco, Bogotá in the 90s, remember). Never in my life would I have thought young people could be… so… soulless. Depressed? Yes. Hijosdeputa? Yes. Killers? Yes. I’d been robbed by young boys on the streets before, kids barely over 5 years old sniffing boxer, sleeping next to their knives. Junkies? Yes—Catholic school for them daughters of coqueros. But a state of mind robbed completely of humanness, fifteen-year olds humming like a machine, and brought to life through the stupid repetition of prayer: hijos de Dios.

Inside everyone around the circle lifted their hands in a let’s-slap-some-high-fives gesture. Disgusting, I thought. I didn’t want to touch everyone’s hands but Wilson the youth leader, who we’ll call Young Mulatongo, grabbed me by the elbow and skipped around the circle holding out my arm. Are these people blind? I’m punk. I’m an artist. I fight bitches on the street. Once in the middle of la 82 I spat on this girl for calling me a chirri (I did run right after. But still).

But where could I run? The condescending smiles. Two girls in matching shiny flip-flops held tambourines fake smiling and only barely touching my hand with their fingertips. Okay mi vida do it for your mother who worked her costeña butt off to get that visa and who is ecstatic to be in this church (no one could shut her up about it months before we moved here), and if you just behave today maybe later she’ll forget all about it and you’ll be able to stay at the townhouse and think of ways of not killing yourself yet. Cool.

The Young Mulatongo shook his finger in front of me.

Eeee-cume niña, hellooo. We’re down by three people tonight we need to increment our Sacred Outreach Efforts.

Some of them yawned. Others swayed their arms to the baby blue ceiling. Everyone was instructed to bring a friend and share their Life Changing Testimony. Then in came a young morena from Barranquilla in one of those sheer white gowns, waving off the Young Mulatongo but flirting with him, passing out pamphlets with light exploding from grey clouds.

Okey, pelaos, this is how it’s going down. I want all you lazy disque followers of Jesús to get that culo moving or else we’re buried, me están oyendo? Tonight go home and think of that friend, that lonely ugly child with the Metallica shirt next to you in English math Spanish government class that is in desperate need of saving. You know the kind. Yes? And you bring that ugly, godless child next week and here we will strip him of that shirt and he will smell of pachouli and we’ll deal with Dios and he will be one of his soldiers are we all full cleaaaaar pelaos?

They all went wild, cheering, throwing pillows in the air, bibles flew. Girl is a preacher. This girl has my attention. And just like that, that ugly Barranquillera and her authority, and her pimples demanding with no respect whatsoever that we—that I—do exactly as she said.

- Published in Series

THREE POEMS by avery r. young

new testament

i.

in temple

mudda: boy!!!!!!!

gonna make my hair fall

worryin if yo life

still on dis side

of groun(d)

us been three day(s)

lookin fo u

u in herr

runnin

yo mouf

hey-zeus: dunno y

u worryin

bout me

u know

whatchu had me fo

i handlin

my father

bidness

mudda: my God!!!!!

ii.

at wedding

hey-zeus: woman!!!

i aint no magician

mudda: boy

u aint gotta tell me

what thou art

i know who

u come from

but

u came outta Me

i say we need wine

& de angel already tol(d) me

how u gotta do

now

ax yo daddy

fo summa dat joo-joo

& see if him work(s)

like him say

him do

iii.

at table | after cross

mudda: God.

u aint tell me

him wud bleed

like dat

. dam(n)

god:

iv.

cabin in sky

mudda: after

dey kill(t) u

folk wud snatch

life from mudda(s)

in prayer

& soil de mudda(s)

in dey own crimson

& scream(s)

& de mudda(s) wud

tell dem no

& dont

in front of my baby(s)

but

dey wud take de mudda(s)

& de baby(s) too

& de men who knew

what yo face look(d) like

in de dark

enuf to kiss it

hey-zeus

dontchu know how many

commere wif yo name

in dey throat

dontchu remember

de one time

u open(d) de sky

& u ax(d) dat one

muddafukka

y him yo electric chair

dontchu remember how

u change(d) him name

& way him sword flew

open de sky

now!

open it!!!

& snatch de evil

from dey palm(s)

turn deez muddafukka(s) paul

hey-zeus

turn dem all

little red

fo Toni

& when him come mandingo buc(k)

all greasy & blue in de hush

of her befo her give him a piece

of summa dat blow

a min(d) | her tell him

some man rape(d)

some woman her kin to

somewhere one day

& ran saffron

up & down

her | her tell him

her blk not almos(t)

white | her tell him

dem be razor(s) not roller(s)

curlin her hair

her tell him her aint a prize

wif a pussy

her tell him

her pussy de prize

her tell him

her need him to be

a winner | her tell him

him has no option

to lose

status 3

6.18.15

as far as i be concern(d)

dem n’em made jee-sus

de 1st transracial mudda- fukka | ever

blk!

- Published in Series

FWR Monthly: August 2015

The idea of voice has been hot on my mind lately. I think the ongoing work of folks like Amanda Johnston (one of the founders of Black Poets Speak Out), has made me think closely about how I move through the world, speak for myself, for and with others. Voice is subjective, relative. It’s also incredibly relational. Although I’m not a thousand percent behind Naomi Wolf’s talk of vocal fry, I know well the phenomenon of adapting one’s voice to suit one’s audience. The question is, then, from which conventions and collectives does one draw? And why? A writer performs on the page for a hypothetical audience, introducing herself to strangers again and again. Whatever voice that writer inhabits at any given time should be considered and relevant, and it should always feel true.

Since this is my first monthly curation of Four Way Review, the theme feels apt. As editors, we think about our own voices, our voices in conjunction with other editors’, and how the pieces we celebrate reflect upon us. Last month, Ken Chen, Executive Director of the phenomenal Asian American Writers Workshop, wrote an article excoriating certain white artists whose so-called transgressive work does little more than parrot the language of violence, racism, and patriarchy. Another recent editorial at Apogee raises the idea that it is as impossible – and unethical – to “read blind” as an editor as it is to be colorblind in the way we engage with each other in the flesh.

Here’s my secret: I was a little tempted to name this issue The Anti-Rachel Dolezal Life & Times, for the sake of those of us who have worked very hard to be ourselves, to own where we come from, and to make art from that space. The aforementioned – now-infamous – identity thief, who has worked with visual media in the past, was, unsurprisingly, once accused of plagiarizing a landscape by another painter. The appropriation of style, voice, and culture all converge so neatly in her story, it’s remarkable.

With all of this roiling in my head, I found myself, more than anything, wanting to read gorgeous, powerful voice. Just that. Inventive, not necessarily confessional, but representative of the artist in an elemental, charged way. When I started feeling tired of tired voices, avery r. young and Juliana Delgado Lopera came to my mind immediately, as the balm I wanted and needed most.

I bet you’re going to like reading these folks. Their styles are very different: young’s work boasts spareness and abbreviation, often using the architecture of parentheses to slow the reader, to encourage and reward re-reading. Lopera’s narrator, on the other hand, has fluidity and grace that’s enviable. Both are immediate. Neither backs down.

It wasn’t planned, but I don’t find it at all surprising that, in young’s suite of poems and Lopera’s excerpt, both use Christianity as a springboard for their characters’ voices. Owning one’s voice often comes from looking directly at structures of power, the stories we as a culture swear by. I think it’s important to reclaim power this way. And maybe it seems naïve, but I feel the connection between the art we make and support and the way we engage each other in the world is very real. These two artists are doing the good work.

~ Laura Swearingen-Steadwell

Poetry Editor

excerpt from FIEBRE TROPICAL

by Juliana Delgado Lopera

NEW TESTAMENT

by avery r. young

- Published in home, Monthly, Uncategorized