ISSUE 26

POETRY

TWO POEMS by Sasha Burshteyn

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT UNSONNET by Dante Di Stefano

TWO POEMS by emet ezell

TWO POEMS by Sebastian Merrill

SO MANY by Robin LaMer Rahija

WHY HAVE CHILDREN WHEN THE WORLD IS ENDING by Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach

TWO POEMS by Tana Jean Welch

ELEPHANT by Julien Strong

WHEN BILLIE HOLIDAY SANG by Grace Kwan

FABLE IN WHICH YOU ARE A BARN ANIMAL AND I AM A CARNIVORE by Hannah Marshall

JUNCTURE LOSS by Liane Tyrrel

TWO POEMS by Julia Thacker

FICTION

WET OR DRY by Naomi Silverman

BLOODY AVENUE by Isabella Jetten

TRANSLATION

ANCIENT MOSQUE by Xiao Shui trans. Judith Huang

THREE POEMS by Sandra Moussempès trans. Carrie Chappell and Amanda Murphy

THROUGH THE LAKE, THROUGH THE WATER by Johannes Anyuru trans. Brad Harmon

THREE POEMS by Álvaro Fausto Taruma trans. Grant Schutzman

THE GARDEN IS THIS GARDEN by Hélène Cixous trans. Beverley Bie Brahic

CHEWING BETEL NUT by Mark Dorado trans. Eric Abalajon and Mark Dorado

THREE POEMS by Anne Vegter trans. Astrid Alben

INTERVIEW

with Carrie Chappell and Amanda Murphy

ART

- Published in All Issues, ISSUE 26

INTERVIEW WITH Amanda Murphy and Carrie Chappell

Winner of the 2022 Théophile Gautier Prize in Poetry from the French Academy, Sandra Moussempès’ collection Cassandre à bout portant (Flammarion, January 2021) explores the haunted aesthetics and violent dialects attributed to women’s lives. Raw and rigorous, the poems in this collection channel women’s voices as they disembody and re-embody in language, tapping poetry’s potential as a space of rebellious empowerment.

FWR: How did you both (or each, if separately!) stumble across Sandra Moussempès’ book, and what about it called out to you? Was there a particular quality about it—or even a particular poem within it—that led to the “coup de coeur,” the lovestrike, the desire to rebirth it in your mother tongue?

Amanda: That’s what usually happens to me when I really love a poet or author whose work is not yet translated, but in this case, Sandra actually reached out to me through a friend in common. I dove into Cassandre à bout portant with the idea of translating it and it became immediately apparent to me that these poems needed to exist in English. They often rely on imagery associated with the United States, Hollywood cinema, advertising, and the stereotypically feminine that we can trace to those spaces, so it just seemed logical to me to bring the poems into the language of that world. I would say that my reading experience was already infused with the idea of a translation to come, and that for me, these poems have a particular call to be translated into English that I felt I could respond to. But I didn’t think I should translate them alone. So I reached out to Carrie, a friend and poet I admire greatly.

Carrie: For me, there was a bit of stumbling across the book. The day after I spoke with Amanda about the possibility of working on a co-translation of Cassandre à bout portant, a book I did not know by a writer I had not heard of yet, I assisted an old professor of mine in finalizing a large order of his at the Tschann Libraire on Boulevard du Montparnasse. While waiting on him, I drifted towards the poetry section, and, there, in a face-out display, was Sandra’s collection. Because I had already been clutched by the conjurations of the title (a linguistic pull which remains rather undiminished for me when I think of this work) and because the object itself was so electrically pink, I found myself rapturous to pick it up. I already knew this was my copy. I bought it. It felt like a big yes. It felt like good chemistry. It felt like the best kind of adventure to embark on with fellow writers and feminists.

Like Amanda, when I read the poems, I had translation in mind and felt quickly how their lines contained refractions of my homeland, elements that had romanced and troubled me. The book seems to be particularly infatuated with women who have in their enshrinement been ensnared. And Sandra traces that through, yes, cinema but also very surely through the “tragic” women — Emily, Virginia, Sylvia (for within the work they are almost always invoked by first name) — of English literary tradition. I felt, then, that Sandra’s project, while certainly moving to me, could also speak to a larger audience.

FWR: What led you to decide to undertake this project together? What is the process of co-translating like for you, and what do you think are some of the unique boons and challenges of having a companion in this kind of experience?

Amanda: Sandra Moussempès’ poems speak of and to women. They inspire sorority and solidarity, which is actually an approach to translation that I had already studied in particular among women translators in Québec. It seemed to me that this was a unique opportunity to put it to practice, precisely because the work seemed to call for women to come together in language, to find a common voice that contests the norms usually imposed on it, which translates in the poetry to a kind of paragrammaticality and awareness of being a woman in language that I think Carrie and I both identify with. For me, the positive elements of this experience with Carrie are so overwhelmingly dominant. Getting to have a second set of eyes and ears, a second experience with the text to compare to, and a larger sounding board for ideas while translating is such a rich experience.

Carrie: The plurality of women’s voices, what feels like archive at the same time as new utterance, in Cassandre à bout portant is what has made me feel that this work in particular necessitates more than just one mind considering its English articulation. Amanda and I, perhaps due to our previous creative and research-based work, seemed to both desire a process that would allow us to not only work on the word- and expression-level matter of the poems but also to interrogate what the work was doing in time, both literarily and to us. I have very little doubt that Amanda could have translated a version of this book on her own, but if she or I had gone forward independently, we would have denied ourselves a lot of meaningful conversation around French and English expression, as they relate to the narration of women’s lives.

FWR: What have been each of your journeys into the world of language and then into translation specifically? How did you each meet and fall in love with poetry? With French? I know that you, Carrie, are a poet, and you, Amanda, are a scholar of comparative literature. In what ways do you feel the act of translation connects with, diverges from, and even influences your individual writing practices?

Amanda: Language for me is a tool for emancipation: be it a “foreign” language or a particular use of, or creation within, a language we consider native, speaking and writing is about finding a voice. It’s about bringing something into existence – be it a voice, a concept, or an image – that didn’t previously exist, like one of my favorite poets Nicole Brossard expresses through the notion of “l’inédit” (the term she uses to describe something that has been denied by language and society but that can be brought into being). This is what fascinated me, as a young woman, about foreign language, and this is ultimately what I have come to appreciate about poetry and literature in general. In my research, I’ve been particularly drawn to writers who push the limits of language(s) or rely on multiple forms of enunciation to express their relationship to language(s) and the space(s) to which they’re connected, and which usually has a political element to it. This is why my interests in literature began with the most “radical” forms — the historical avant-gardes and modernists (Kafka, Djuna Barnes, Faulkner, Joyce, Woolf), as well as the Language poets in the U.S.

I never really distinguished poetry and prose and have never been interested in genres as categories (which doesn’t mean they don’t exist; these are just not the questions that are the most interesting to me). For me, it’s a matter of doing something with language.

Translation is directly connected to this idea, as it is a practice that by definition brings something into existence, but translation for me is also a process working from within a language. It can be part of a poetic gesture; it can be found within a word choice, or can leave merely a trace, a hint of elsewhere, which is what I often find among the writers that interest me the most. Personally, I find it impossible to write in only one language, as translation is always there – the back and forth movement is part of my identity and therefore part of my writing.

Carrie: It’s a humongous question, Marissa, but still such a worthy place to attempt response. My journey into the world of language has been a process, a long and ongoing one, of understanding my linguistic inheritance — all those weird underpinnings that made up my expression at home in the U.S. Southeast and then within the larger context of “universal,” or what I really think of as colonial, English — and then looking for ways to disinherit or revolutionize the grammar of my thoughts so that I might chance a realer articulation of self or future self. At the same time, I have often been pulled, contrastingly, towards preservation, towards a wish to keep some lineage intact, to be sure I could still feed off the oxytocin of origin.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about, in my own creative work, the trauma that is incurred by a person when she comes to share, as sincerely as she can muster, a truth of herself and is met with denial or ambivalence. It breeds estrangement within the self, and all I really understand is that I believe this might have happened to me as a very young person and that I have gone on to breed estrangement in some of my life choices. Even as much as I’ve been looking for real embrace. I understood at some point that “home” — my South in particular — was not a place where I was or would be accepted. And that translated into a number of places but very really what became my writing life.

Poetry has always seemed to me like a beautiful foreign country, a place where customs are turned on their heads, where the unrequited is given ample room and the hope of audience, where dreams are suddenly documented. I believe that if you are writing anything that you call a poem, that you are writing from a place of estrangement, from a place where you have felt your thought or vision was disadvantaged by the current stakes of reality. And so you write to contextualize yourself, which is in a sense giving yourself a new country. I have needed poetry for this above all else, I think.

The act of translating poetry feels to me like another way to be a good citizen to the estranged out there, and it is also a great experiment with a “tool for emancipation,” as Amanda said of language. In seeking the English expression for Sandra’s poems, we’ve had to interrogate responsibility in English and in literature, which is a terrifying but fascinating space to enter in regards both to communal and personal conversations around creation.

FWR: As Americans who have spent years building lives in France, has immersion into the world of French literature altered the way you look at the writing of your homeland? In the same ways in which many people trace the lineage of aspects of contemporary American poetry to writers like, say, Dickinson or Whitman, what do you feel is present (—whether being hearkened to or pushed against—) of the foreparents of French poetry in contemporary writers? In Moussempès specifically? How do you feel having access to modes of expression outside of the Anglophone influences the ways in which you view, understand, and imagine literature more largely?

Amanda: In my case, foreign language, or a certain foreignized relationship to English was what drew me into literature. I have been particularly interested in the incapacity to feel at home in one’s own language and to the potential mechanisms of exclusion or oppression contained within languages that function in different ways depending on the language and its historicity. Sandra, I believe, writes with the presence of a community of women poets, contemporary and past, who have also suffered from exclusion or oppression (Plath is a very important figure for her, I know). She draws attention to the difference between being (or identifying) as a woman and the expectations society has had, and still has, for women, including in language – how to speak, how to respond, what you can and can’t say.

Carrie: Yes, building a life in France, which absolutely meant for me building a stronger relationship with contemporary French literature, has changed the way I look at the writing of my homeland. Firstly, my move here, as probably many who’ve made similar choices to uproot from homeland might attest to, pronounced for me very clearly my nativeness, which began to feel a lot like an almost impolite level of naïveté, to my homecountry. Even the American-ness I knew I was trying not to perform almost compulsively emerged from me. My whole sense of self-worth had to be reappraised, because I no longer held in French society the obvious markers of anything except my biographical information. If I considered myself having had any “success” in the United States, well, nobody here had ever heard of a lot of my stuff, especially an MFA. But what this meant, painful as some of it was, was that I could kind of reappraise the hold America had on me. I still write myself a lot about my South, I’m still fixated in so many ways on looking back, over, under, etc., but I’m also now more freely accepting that my homeland shouldn’t need to take up so much space, in my relative sense of how much I matter and in a global sense of how much it matters to other lands.

As far as what I feel might be in revolution in French literature, I think a lot and not enough, all at the same time. Institutionally, what we have as an example with Sandra’s book, which is released by a major press (Flammarion) in France, is a reminder that here poetry is recognized as a living artform, but I don’t think you see these major presses supporting, mostly through PR and events, their poets in the same way they do their prose writers. And I guess the French public isn’t either. Which means that poetry in France remains, for better or for worse, niche.

For me, this “nichitude” goes back to the earliest moments of education around poetry. French children are still required in school to learn certain poems, mostly themed around the seasons or school supplies, by rote memorization and perform them for their teacher and classmates. These poems have heavy rhyme scheme and meter, and are, I believe, meant to promote a certain formality around pronunciation and elocution. While I was initially charmed by this practice, I’ve learned that the poem, the poet, poetry as an expression, are given small parameter. The poem stays fixed in the classroom as exercise. After that, by the time of the final graduation exam, French youth are expected to have evolved and asked to be more literate in literary technique and prosody but as applied to a limited canon of white male poets — Apollinaire, Baudelaire, Char, Hugo, Ponge, Queneau, Rimbaud, Valéry, etc. And this is, I guess, what many French people here leave their education with, that poetry has been written, that it has intellectual properties and even “a message,” but that it is stowed in the past, in the hands of these men, these practically mythological names, that people around the world include when they refer to “French Literature.”

So, I have some difficulty tracing all that contemporary French poets are pushing against. It is practically everything. Every rigid exclusion of diversity, every dictation of poetry as something that must have strict formal structure. And it’s pretty challenging to go through historic or contemporary European artistic and social movements and find parallels in poetry publishing because it seems the French taste for poetry has been greatly reduced by this rigidity. French women in this tradition are very underrepresented, as are people of color. We have some cultural nodding around names like Andrée Chedid or Suzanne Césaire (though we usually hear more about her husband), and if we go back further, some might recognize Marie de France, Louse Labé, or Anna de Noailles. People still get excited by the Oulipo movement, and it did touch poetry in France. Yet, I have my doubts about whether it really expanded any conversations around who gets the preservation of publication, the reissuing, etc. Only six women were “inducted” into its club-like structure and few of them have been translated. Hélène Besette, who was not a member but who was first published by Queneau, is one of my absolute favorite French poets. She was enormously inventive with her “roman poétique,” but she was practically excommunicated from the scene because she wasn’t an “easy personality.” It’s taken several small presses to resuscitate a readership for her, and I have heard that she will finally have English translation in the coming years.

I think the French poets writing today are working towards more radicalism, both on the level of the line and articulating identity, than some of the celebrated men of French poetry tradition ever dared. Sandra Moussempès certainly is. And she is doing so in the purest promise to an artist’s life, and she’s doing it well and often. This is her 11th published collection. This time, finally, garnering attention from the French Academy. It’s a big deal, even if receiving an award wasn’t going to dictate her future artistic production. Where is she taking her inspiration? I’m not always sure. Certainly, she’s looked to the U.S. She could be drawing, as are others, from what has been long and powerful social discourse in France on feminism. Today’s “wave” is absolutely more intersectional and is strongholding with feminist and queer writing collectives. And what’s powerful in that right now is that independent presses and young people are showing up for it and are feeling more and more empowered to turn back to their institutions and say, actually, I think this, over here, is really good literature. I’m very inspired by my French contemporaries who are dismantling the “preciousness” of literary forebearer so as to expand what art can do. It is amazing radical love.

FWR: When I first read through the Moussempès translations that you sent, one of many qualities that I was drawn to was the formal expansion and contraction, almost tidal, in her work, and the way in which it seemed to mold with how the theme of female embodiment ran across these poems. There are several poems that feature very long, almost breathless lines; others are incredibly spare. How do you see form, in this sense or others that strike you, operating throughout Cassandra at Point Blank Range? As translators, were there any tricky formal, rhythmic, or verbal decisions you had to make to bring Moussempès’ verse to life as you had understood it?

Amanda: The formal expansion and contraction in her work is definitely an interesting element. It’s what gives a certain rhythm to the whole book. For me, it’s necessary to consider rhythm and form on various scales: the line, the page, the poem, the collection, the book. There is definitely an importance given to changing shape, perhaps to the plasticity of women’s bodies and to women’s ability to adapt, with all the implications that can have. When translating Cassandre, we definitely had some moments where we were unsure of the need for a line break or a page break, and even on some occasions had differing opinions as to whether or not a poem ended before or after a page-break. Generally speaking, we tried to protect the rhythms found in the original, but as her poetry is also quite prose-like, we had to find a compromise between the semantic unit and the sounds and visual elements.

Carrie: I agree so much with your descriptor of “tidal” Marissa and with Amanda’s identification of Sandra’s expansion and contraction of form mimicking “the plasticity of women’s bodies and […] women’s ability to adapt.” I think of this collection as a series of short films strung together. Sandra’s work is so cinematic to me and because we find it all on the page with sound and image bites patched in here and there, we also have the sense of the fleeting, the ghostly, a staging but of a kind of absenteeism. I do see Sandra’s work as keenly interested in exhausting the reader’s ability to locate, as a way of forcing us to accept the speaker or the author almost as medium, bringing in messages from another consciousness. Like Amanda said, we had to work through a lot of questions. In some cases, we were looking at where to build cohesiveness with certain word choices, so as to engage “readability,” but then, we worried to what degree we were projecting a certain narrative-wish for the poems. I do think we decided early on that as far as translation would go, we would, in as many cases as it was possible, aim to maintain a semblance of the original rhythm of the text so that that “tidal” quality, which feels very Moussempèsian, remained.

FWR: Was there anything in Moussempès’ work that you found particularly challenging to translate? Do you feel that the act of translating these poems gave you access to anything that you might not have had were you simply reading them?

Amanda: Poetry always relies on a degree of ambiguity and meaning can be located on so many different levels, so yes, in Cassandre à bout portant, we definitely had moments where Carrie and I didn’t necessarily come up with the same understanding or feeling about a word or a line that was particularly unique. Line breaks were often a challenge due to the ambiguity of meaning they can create depending on if you read through them or stop. Sandra’s forms and use of punctuation is not always consistent, voluntarily probably, so it is sometimes hard to come up with any kind of method or rule for translating.

Reading is the first step in translation, and reading definitely determines translation to some extent; however, there is something extra in the gesture of translating that can feel empowering, depending on the text, and on the translator’s relationship to it and to the languages involved. There were a few poems, especially the ones about writing and women in language, that gave me a really great feeling to translate, the feeling of enacting, in a sense, what the poem was originally trying to say or do.

Carrie: Yes, I think Sandra’s poetics, which for me include a certain disbelief in traditional grammar practices, were probably the most challenging for me. For example, a misplaced modifier in French is misplaced still, but it can, within the rhythm of the language and the order of preceding words, be felt in a particular way. It was delicate to try to replicate that purposeful misplacement in English phrasing. We couldn’t always achieve it.

I also think the repeated references to U.S. culture through cinematic, literary, and brand mention represented an intriguing moment in the consideration of how these poems would transpose. When the speaker in “Non-identified feminine objects” mentions Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, chewing gum and corn flakes, we had very little translating to do, of course, but I do think we considered what was intact in Sandra’s French and in our reading of her poems, which is a kind of mystique in importing another culture and language (and honestly time) into her work, that we just can’t deliver in leveling it all into English, and our American English at that.

FWR: Translation can also be seen as a kind of editorial curation. It’s a process of decision-making—out of all of the books I come across on a regular basis, this is the one that has moved me irreparably, that I believe can touch others in far corners of the earth. What does it mean to you to think of not only the artistry, but also the responsibility, of literary translation? In earlier eras of your lives, as burgeoning young lovers of language and literature, what translated works were most formative to you and what you believed writing could be?

Amanda: There is no doubt that translation is determinant for literary culture and canons. The existence, non-existence, or delayed existence of translations has shaped our ideas of what literature is or isn’t, what it can or can’t do, and what it can or can’t say. Translating in itself is an occasion to reify or modify those beliefs and I have always admired translators’ initiatives to make something happen through translation, to bring about an event in language, even if it may be highly personal or concern, at first, only the translator’s relationship to the languages at hand. I can’t say I grew up reading with an awareness of translation. When I became interested in translation studies several years ago here in France, I came to the conclusion that a lot of the translations I had read at school in the United States, for example, had not even been presented to me as translations. There is a real problem with the dominance of the English language and the lack of interest in foreign languages in the United States in certain milieux, and that’s part of the reason why when I translate, especially into English, I adopt at times a foreignizing strategy, leaving traces of something that might remind readers that they are reading a translation. I believe that is essential to a responsible experience of reading in translation.

Carrie: Well, I guess I referenced some of these ideas a bit before, not knowing this question was coming! I do, though, see responsibility in literary translation as a very real concern. I have greatly enjoyed learning from Amanda’s research in translation and felt swift community with those she introduced me to who believe in maintaining some of the original’s grammatical structures, even if there might be something more economical in English, so as to honor the anatomy of the author’s lyric. A part of what attracts me to translation is what has also made me a poet, which is a wish to devote my whole self to the choice of words, to each word. I think of this practice as one that is fully artistic and fully responsible. I don’t know if I’ve ever disassociated the words when I‘ve thought of the social/political/artistic act that is presenting work to an audience.

In high school, I remember having a very powerful reading experience with Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. However, much like in Amanda’s story, I don’t remember being presented with this book, which I think must have been assigned reading for one of my classes, as a translation. (The same is true when I think of how little was said about how Sophocles’ Antigone or The Diary of Anne Frank came to our American English classrooms.) But if I recall well the kind of strange font choices and paper grade of the cover of my copy of Crime and Punishment, it was one of those cheaply marketed versions of “great literature” that you could find in the front aisles of Barnes and Noble. Certainly, I felt in reading it that I was being pulled into a different culture — the character names were difficult for me to pronounce even in my head, the small food references were obviously “other” to my parents’ homecooking, and the old religion didn’t feel anything like my then American Protestantism. I loved the series of weeks I spent in that book, yet didn’t spend much time interrogating how I was sitting in my carport in Alabama with this text. It was still several years before I would be taught, and then actually grow interested in, the front and back matter of books. But because of these occlusions and the sometimes clinical way novels were taught to me, I don’t think I had any inkling that “literature” was something that I could write, that translation was something that I could do.

FWR: What does it mean to you to translate from a foreign language that you are also both currently living within? What are the ways in which you feel it smoothens the process or ways in which you find it complicates it? I remember, when I first moved back to America from France, how often the French word for something would come to me in conversation before the English word (even now, four years on, my brain can never manage to find me the English equivalents for terms like parcours or régulariser). Do you find your minds blurring the borders of the language it feels most “at home” in, and if so, how does that affect you as not just translators, but as writers yourselves?

Amanda: I think translators, by the nature of their work, always live to some extent in a gray zone. Like anyone who speaks more than one language, they are constantly swinging back-and-forth from one space to another and develop a particular attention to language, which is also that of the poet, in the broadest terms of the word. Through my academic work and own writing (and living), I have realized that these spaces are never étanches; they are never neatly delineated and writing, like translating, is a matter of allowing for newness, maybe even a language of one’s own, to emerge out of the friction between the languages we use, but never fully possess. Even after living in France for 16 years, doing a PhD here, and claiming to be close to bilingual, there have still been words and expressions in Moussempès’ poems that escape me and create an element of surprise. In those cases, I often experience a desire to elucidate but fight against it so as not to flatten the foreignness or strangeness (étrang(èr)eté) in English. That’s where it’s nice to have two translators so that we can compare our respective histories with the French and the English languages.

Carrie: I often return to something Maryse Condé says in the beautiful documentary on her life, “Maryse Condé: A Voice of Her Own” : “The language I write in is neither French nor Creole. As I have often said, it’s a language of my own. I write in Maryse Condé.” When I first watched this film in 2016, as a student in the DUEF department at Sorbonne Nouvelle University, Paris 3, I rejoiced. I was in love. Condé’s determination to claim a spot for herself, in all we can think of as self, in the world of literature, despite different worlds demanding something of her to be more distinctly Guadeloupean or more distinctly French, was so illuminating for me. As a poet, I had often felt like some readers had wanted me to shirk certain aspects of my expression that felt so distinctly me to me. I think Condé, who now lives, and has for years, in New York, embraces in ways I want to, in ways I want so many writers to, the particularities of a linguistic relationship to the world. The way one feels and wields and receives language is one of the most personal and intimate spaces I can imagine. It is a sensuality. And I think “living in French” as a native English speaker has offered me new sensual dimensions in the expression of self and reality. Of course, I experience complications. Like you Marissa, certain English words “go missing” on me. It seems my brain has almost permanently deleted a referent for what might be an English equivalent for “préciser,” but I don’t know if I could say that anything about living in France burdens the process of translation from French into English. The process itself, no. Perhaps a question about publication, being farther away from the English presses that might want to release a translation, is a different order of question. Yet, I think it actually makes a lot of sense to be within the culture from which you are translating some of its works. At the same time, of course, this could never be a requirement, but for me, living in France and working on Sandra’s book has afforded me a collaboration with Amanda and also regular contact with the poet herself. I feel extremely lucky to be local in this way, to have the constant stimulation of French in my daily life. All of this leads me back to what I wanted in moving here, which was a kind of solidification or amplification of the linguistic plurality I already felt in me.

THREE POEMS by Anne Vegter trans. Astrid Alben

With permission from the publisher

WILDCARD

A light-hearted lullaby this, not much happens

that doesn’t already happen somewhere else:

a garnet-red baby opens wide its tiny jungle mouth.

Familiar to all who read them, lullabies are

about kisses, jealousies and parents / keepers.

Raging in the pillow, rising like a statue made of ash.

A parent is a house. Gooey goo-goo. Food, milk,

lalala. A lullaby disentangles love.

Be joyous and light touch. Filter light,

the air is of an invaluable purity.

Compared to wellbeing I daresay it’s cloud-cuckoo.

Parents / moods / components of the growth machine:

baby’s first, baby’s own, baby’s living it up. Joyous,

carefree bellowing in a sun-drenched nursery. Done.

Hearts plead, hearts steam: Adonai —

give me back my stalemates, my singular days, my intact membranes.

ISLAND MOUNTAIN GLACIER, PART IV

Even when I, in this minute of my kingdom, in this household of seasons (jan steen), in this

temple (breath), leave it all to you (here sweetie, for you) I elevate your thin meat to a spectacle.

Even when I touch the memory of your hips, your hands tiger my uh-huh parts

ingest me (tongue chest lips) and I read my gape from your lips or should that be gave.

Selections from the Appendix

Appendix

Just like a poem, a translation emerges out of its own possibilities. It is built up of layers, alternate states that enter the work and flow through it. Options, possibilities, stabs, trials and errors, interpretations and choices are made, discarded, brought back, revived, knocked about, improved and transformed.

I got to dissect and study Anne Vegter’s craft as I worked on these translations of her poems. This was a gift. More than a reader, a translator becomes the work’s mechanic. I dismantled each poem, uncovered its particulars, brilliance, magical flurries, flaws, oddities and the syntactical, semantic, sonic, rhythmic bones and muscles that hold it together. On my desk, the poems to be pulled apart, experimented on and reassembled in the new language. Like twins wearing different outfits and sporting different hairstyles, the original and the translation are intimately related yet distinctly separate entities.

Translations are like poems, a work in progress. It is nothing more complicated than that. And then, of course, it is. This appendix shares my process, isolating my choices and keeping the layers of possibility visible for the reader to create their own arrangements and, where necessary, to improve the translations. For I am but one of what I expect will be many more translators bringing Vegter’s writing to an English readership.

Astrid Alben, 2021

TRAMPS

You spoke of an emotional chill, below zero you said it was between

my thighs in the departure lounge. After your bag we hugged heart to heart,

I could’ve joyfully sucked you off. Are you even listening?

We resembled wiry birds; you designed a deathblow on paper,

had yourself a little after-fun with your boredom. It got tricky finding reasons that way.

When the glass slips from your fingers you go find a cure for cracks and salt.

The carpet grins. Will finally someone stand the fuck up and hold me?

TRAMPS

You talked about air temperature, below zero between my legs you said in the

departure lounge. After your bag we hugged each other coeur à coeur,

man I could have blown you I was so happy. Are you still listening.

We reproduced rigid birds, a deathblow’s what you designed on paper

had a little after-fun with your boredom. It became tricky to find reasons that way.

When the glass jolts / jumps / leaps from your finger you look for a cure / remedy against cracks and salt.

The carpet grins. Will finally someone stand the fuck up and hold me.

VAGABONDS

You talked about instinct-heat / emotion-temperature, you found it below zero in the

departure lounge. After your bag we hugged each other coeur à coeur,

happy as a lark ready to blow you. Are you still listening.

We faked / forged / imitated rigid birds, you designed a deathblow / deathly fall on paper

had some after-fun with your boredom. It became tricky to find reasons [in] this way / method / manner.

If the glass leaps from your finger you look for something / a cure against cracks and salt.

The carpet / rug / runner smirks. Will someone stand the fuck up and hold me.

Astrid Alben is a poet, editor and translator. Her most recent collection is Plainspeak (Prototype, 2019) and Little Dead Rabbit (Prototype, 2022).

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

CHEWING BETEL NUT by Mark Dorado trans. Eric Abalajon and Mark Dorado

This mouth

grows in it a forest

born from the spit

of the gods

of my land;

chews a wildfire

that blackens the stumps of my teeth;

hums the serenade

of our greatest hunters.

This mouth can utter to life

the many names of our ancestors

the conquerors could never

wrap their tongues around,

the ones they spat with regret

as their teeth disintegrated,

choking on the sharp

inflections of the names

of our oceans,

mountains,

warriors.

Oh, to speak

of love and freedom

is cruelty

to a colonizer’s tongue.

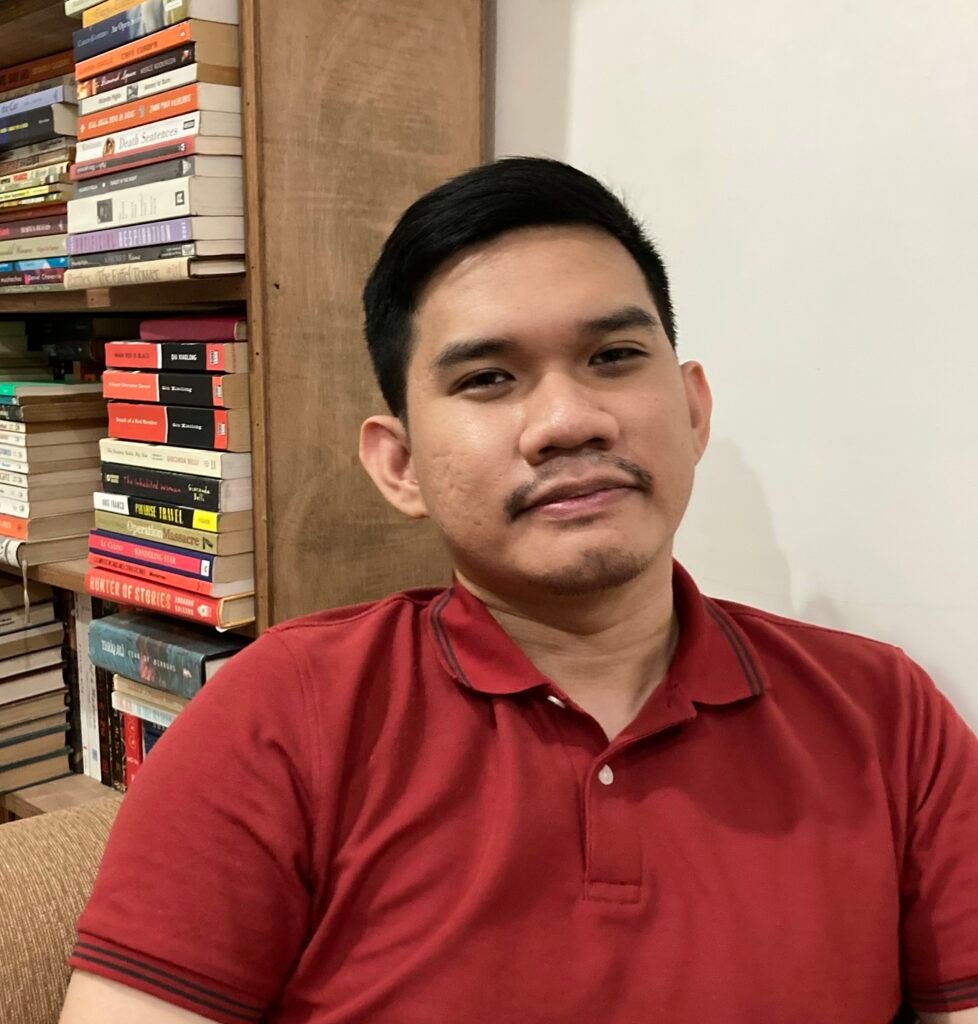

Eric Abalajon is currently a lecturer at the UP Visayas, Iloilo. His works have appeared in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, The Tiger Moth Review, ANMLY, Modern Poetry in Translation, Asymptote, and Footprints: An Anthology of New Ecopoetry (Broken Sleep Books, 2022). He lives near Iloilo City.

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

THE GARDEN IS THIS GARDEN by Hélène Cixous trans. Beverley Bie Brahic

|

My days come and go, their almost motionless river is swept with traces, am I in the river’s current or on the edge? I see the shores of Lethe. The river repeats itself unchangingly, on and on, endlessly until we heave ourselves, the river and me, out.

The garden is This Garden. This garden is populated with an indefinite number of presences and visits. Seated on a bench, This Bench, I almost don’t notice a furtive future thought that thinks: I was sitting on This Bench, at the corner of the house where the cat goes out of sight, where Eve my mother, seen only by my hallucinating eye, sits in her usual chair under the strawberry trees.

Memories? No memories, no reproductions of visitors in an album frozen in time but waves, glints of reflections, of instants, bits and pieces, allusions, syllables, sometimes just letters, but capitals, a swarm of winged motes, the dead are not dead, all my old cats go by, hurried thoughts between the paths of present cats, a characteristic of this populace is incessant movement, I do not know what drives them, is it the wind, the spirits, the gods, my beating heart? –No one is dead as long as I am here to greet and traipse after them –Do you remember my sonnet 81? Shakespeare says, the sonnet that has kept me company from May 26, 1954 to this day May 26, 2020, we’ve never been apart, today is the same May 26, between us immortality reigns, a love which does not alter that’s why we are able to remember a sonnet, inscribed in the magic stone of the book: I open Shakespeare and the young sounds of the sonnet prophetic of our mysterious future memories are written on its paper lips. ‘Your monument shall be my gentle verse, / Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read.’ I have never been able to read these lines in vain, sixty-six months of May readingreading

from ‘Rêvoir’ , translation forthcoming 2024 from Seagull Books. |

Beverley Bie Brahic is a Paris-based translator and author of four collections of poetry, including the 2012 Forward Prize finalist White Sheets. Her translations include works by Charles Baudelaire, Yves Bonnefoy, Hélène Cixous and Francis Ponge. Guillaume Apollinaire: The Little Auto was awarded the 2013 Scott Moncrieff Translation Prize. (Photo Credit: Michael Brahic)

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Álvaro Fausto Taruma trans. Grant Schutzman

CEMETERY OF THE DROWNED

To my shipwrecked brothers on the island of Inhaca

As your hymn hangs above the mouth of the castaway I call out your name, I call you with this tongue whose words are more than just a soft murmur, a sob, a liquid wound, a widow’s voice, an estranged orphanhood beyond words. I run the winds of September, the unburied mast of longing, the flower that is your unformed body and I write out the syllables of every tear, here, in this country that you departed and never left. So show me the corolla of waves, the whiteness of a tissue that only you know, an echo, say it to me now. Out here hands dig hollows in the insides of your absence: your mother, my mother, every mother is but one mother when the ship that carries every afternoon returns and an inexplicable rudder leads to a memory of your face. What substance does your body breathe beneath the waters, with what burst of gill? How do you adjust the clearness of the tide, the moss, the plankton, the flora of your exile? Ours is still a body made of flesh, blood and fear and debt growing in unpayable leaps and bounds (and so I write with the fatherland of knees with which one prays, searching for imaginary coins). Tell me of those winds that I have heard only the briefest rustle, of that city where death is a mirror, a spectacle that one paddles across, a shipwrecked dissent. A friend you departed and never were, tell me that the sun will make bloom again the fauna in your eyes (unerasable in the night like in the dreams of fish). Oh, how I too wish for this calmness, your home/ocean where you dream with open arms and set aside the flesh because after all, this is what life is: ephemeral circumstance! So tell me your little lies because here the truth is a revolt held down: fear’s weight on the back of the world, above the books, above the tables worn away by hunger, above the life you chose on that submerged edge of cloud: the stronghold of liquid things.

FACTORY OF SILENT THINGS

Just as the teacher gleans from time his essential tool, I manufacture silence, this loom of words unheard, with the same fire that weaves together the angst of an unfinished life; and yes, from silence we come and to silence we shall return, its fretful whisper soaks my body, and the tree of childhood shadows me with its parched leaves, or the dead landscape of some unnamable season, the September winds sweeping away the summer. Silence, the substance we mine within forgotten verses, how it reminds me of that woman split between farm and phallus, the dewskin above the back of each morning. Like a stone, a graph-paper line, I sharpen silence, I tune silence, and the voices sizzle between its burning blood, calling forth this animal that cannot be slaughtered, the bull slowly chewing its root, I mean, its rage, and they both flow back to its mouth like a blade, a metal whose fire only he knows.

1.

On your back you bear the distance that separates you from your own birth! What voices do you bring, oh recital of time? The flesh burns – animal of space and water – it beheads thirst in public squares of glittering metal. There is no cure for the gangrene in this season of moons and udders, not the blank slate of oblivion, nor the translucent fruit of forgetting. We vibrate in the craters our hearts remake, serpents of wind for hands, gloomy and transfixed, surrendered to Goya’s ashen rifles. Blood condenses where love condemns us – this is the body’s hard burden.

Grant Schutzman is a poet and translator. He is fascinated by multilingual writing and that which has been deemed the untranslateable. His poetry and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Rust + Moth, The Inflectionist Review, The Shore, Modern Poetry in Translation, Asymptote, The Offing, Your Impossible Voice, and Exchanges.

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

THROUGH THE LAKE, THROUGH THE WATER by Johannes Anyuru trans. Brad Harmon

THROUGH THE LAKE, THROUGH THE WATER

The beeches stand there, imposing, untouched,

steeped in time: I wander

through the tall yellow hall of leaves

and listen to the open

chords: October, whoever cries here

cries inwards,

the wood bridge has sucked the salve dry.

The underworldly bamboo flutes resound

through the lake, through the water, the wind is

lead poured into stone molds.

I happen to end up

on that strip of beach

where you and I made love one summer day

in the short dry grass.

There’s a you in every poem,

a courage or a great fear, there are

constellations carved out right here,

spokes of blue in the eye of the migratory birds, the words

you laughingly taught me to pronounce.

And the Black Portuguese

spoken in Mozambique

is still the softest language

I know.

To my ears, all your words sound round and powerful,

like our “love”

or “freedom.”

Days when I

stand with my eyes closed

and feel around. As if by a hard

kick, as if by a caress.

Your short, light-blue summer dress

fluttering away through the burning foliage.

The weather changes sex. The dark lake

solidifies.

Brad Harmon is a writer, translator and scholar of Scandinavian and German literature. His work has appeared in journals such as Astra, Chicago Review, Cincinnati Review, Denver Quarterly, Firmament, Plume, and Poetry. In 2021, he was invited to attend the Översättargruvan translation workshop and in 2022, he was an ALTA Emerging Translator fellow. He lives in Baltimore, where he’s a PhD candidate at Johns Hopkins University.

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

THREE POEMS by Sandra Moussempès trans. Carrie Chappell and Amanda Murphy

NON-IDENTIFIED FEMININE OBJECTS

Cinematic princesses escaping from an Eastward facing convent have long known the limits of where they can go

Fatigued from hours of forest walking, they have taken refuge in a haunted house, abandoned since 1972, they now know that at any moment the story could stop

The film could disintegrate, and they will go back to their well-to-do families in Beverly Hills or to one of the luxurious, seaside subdivisions of Santa Monica

For the moment they chew their wild strawberry bubble gum, listen to Dubstep while wiggling in the bronze corridor, lying on old mattresses spread out over the hard dusty floor

Corn flakes caked on the kitchen table since 1972, the box is draped in spider webs, the advertisements hold the faded colors of the time

We sense something vaporous in the atmosphere, ectoplasms searching for their story, bodies trying to infiltrate other bodies

We do not know what is being woven here, any explanation would be incomplete in light of the breadth of the invisible debates, the voice-overs intermingle:

Where are the memories of which you have no memory?

CINDY SYNDROME (SUPPORT GROUP NEARING EXTINCTION OF VOICES)

Cindy

I’m happy you’ve suggested I be you at first I took it for a vampirization of energy (a modern day masquerade) like an Ali Baba’s cave full of cement receiving its notifications by way of jackhammer but you are not one of those passive aggressive people no one remembers I already possess your voice one day I’ll have access to the kingdom of Olympus through a phonetic wing

Cindy

Her tessitura is currently frozen in the Museum of famous voices after staying in an empty box, a tape recorder from 1972, those machines that look like safes whose inaudible cassettes I’ve kept (I remember the thin magnetic strips I would rewind with my index finger), between the forward and advance buttons we can sense the acceleration of time, “noise reduction” becomes back to the future

Cindy

I presented the thing to myself like that, Cindy spluttering over the translation of another Cindy with a softer voice (Cindy 2 cloned during a marathon of ectoplasms where her paranormal friends met) Cindy in two copies with one small difference that one righter of wrongs and the other ethereal singer had the idea of making a shapeless cake that looked like Cindy 2 we will never know if she force-fed it to disconcerted geese or begged for crumbs of it by the front door

Cindy

It is good to flee condescendence at midnight in glass slippers even if the road is muddy I didn’t force anything side B mixed with precepts and pills from another side A metallic serves as my eyelet lace for king size needles, sewing up an exorcist doll into sound and rags will do

Cindy

Cinderella in her original cardboard box slides up under the fifth wheel of the carriage is upset she mis-steered her project this new definition of the ambiance surrounding the name Cindy amputated by two syllables paper-knife in her mouth reborn before midnight of her cinders is an oracle in immersion please provide the upkeep notice to move up in her heart when the little ghost girl curses the packaging inside herself she must be provided in addition to the survival kit with an expression like on the sly

Cindy

These flowers hung on the back of the waterlily I could plant them out with bluebells my story lends to it half-witch half-sparkling orangeade with a bronze-colored stamp that vacuum-packs you but being there to spread the fire of banalities when poem erupts something other than this other thing that you would like to remember

Cindy

It’s me again too intense before the mirror of dolls drenched with hope they all fit into the frame they search for their reflections in vain we call a princess grown old a queen of carnage well under every relation does not look her age and the mirror turns into a paragraph

WRITING TIME (AND ON THE EXPRESSION “TO TURN THE PAGE”)

Here is the little girl folded over like a page

You open her you undress her you take her with you

You feed her with a fork you slice her

Lengthwise

You entrust her with a page she spreads herself out and wraps herself up with the page

You crush her by closing the book

In theory she is not dead yet she unfolds herself with words

The house of liquid sentences is her main address

A ray of light fastens itself more to the houses/voices than to the invertebrate subjects

Like an eel the little girl lets go of a cry but retrieves it

It’s poetry reduced to black powder then reworked in living dough with a little water

Each pause in a given universe gives off a mystical odor

That we extract without tweezers from a temple above time

I became aware of it – I did not become aware of it –

In sinking my heart like a fork into a fixed memory

In sucking up the features of the guests present during the final scene

Carrie Chappell is the author of Loving Tallulah Bankhead (Paris Heretics 2022) and Quarantine Daybook (Bottlecap Press 2021). Some of her recent individual poems have been published in Iron Horse Literary Review, Nashville Review, Redivider, SWIMM, and Yemassee, and her essays have previously appeared in DIAGRAM, Fanzine, New Delta Review, The Iowa Review, The Rumpus, The Rupture, and Xavier Review. Each spring, she curates Verse of April. She holds an MFA from the University of New Orleans’ Creative Writing Workshop and is Instructor of English at Sorbonne Panthéon University.

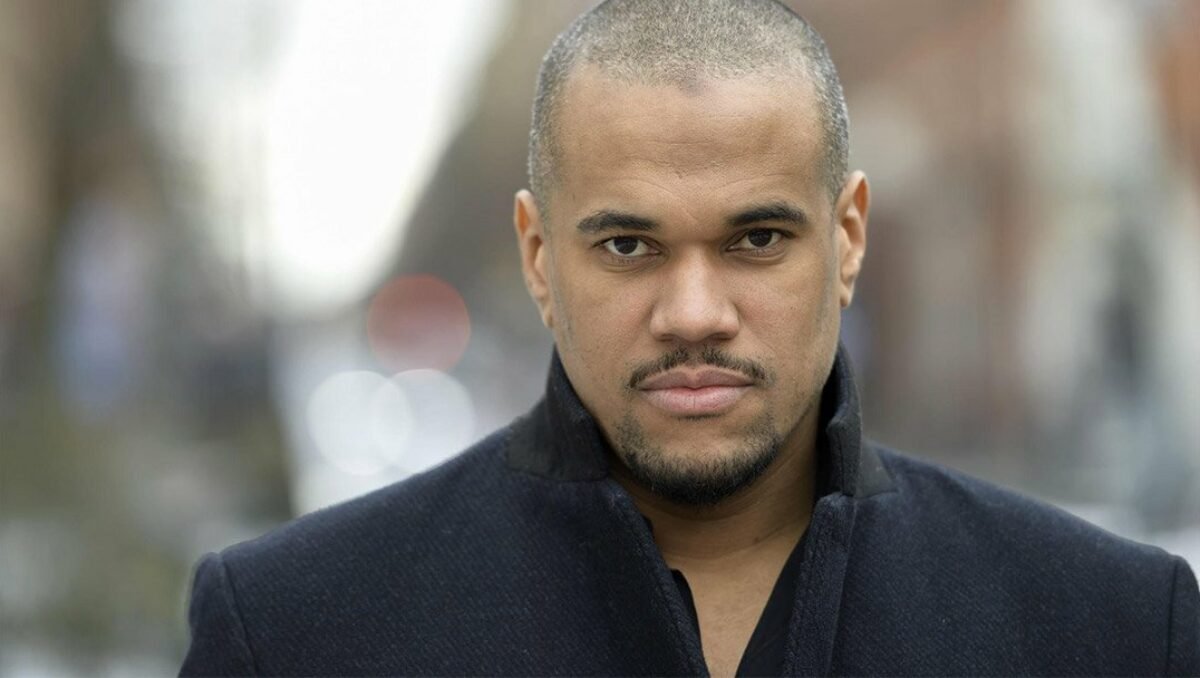

Amanda Murphy is an Associate Professor in English and Translation Studies at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University and a translator living in Paris. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from the Sorbonne Nouvelle and is a member of the Centre d’Études et de Recherches Comparatistes (CERC). Her doctoral dissertation on multilingual, experimental writing, “Écrire, lire, traduire entre les langues: défis et pratiques de la poétique multilingue”, will be published in 2023 by Classiques Garnier.

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

ANCIENT MOSQUE by Xiao Shui trans. Judith Huang

Slightly tipsy, walking out of Hongbin Tower. Two hearses appear

on the bike lane. The invisible corpse, shut in a hand-pushed metal box covered

with black brocade, jingles, bangs and clatters, squeezing through the onrush of head-spinning traffic.

Tightly-packed pedestrians scatter loosely in the smog, all eyeing him, intent on helping him find an opening.

Judith Huang (錫影) is an Australian-based Singaporean author, Rosetta Award-winning translator, musician, serial-arts-collective-founder, Web 1.0 entrepreneur and VR creator. Her first novel, Sofia and the Utopia Machine, shortlisted for the EBFP 2017 and Singapore Book Awards 2019, is the story of a young girl who turns to VR to create her own universe, but when this leads to an actual big bang in the Utopia Machine in a secret government lab, opening portals to the multiverse, she loses everything – and must go on the run with only her wits and her mysterious online friend, “Isaac,” to help her. Can she save her worlds and herself? You can see more of Judith’s work at www.judithhuang.com

- Published in ISSUE 26, Poetry, Translation

BLOODY AVENUE by Isabella Jetten

I’ve been followed around by a younger version of myself since I was sixteen. She wears a pink cotton dress, white, buckled sandals, and a Ghostface mask she cycles blood through using a piping mechanism in her left hand, making the white face drip red. As we trudge down Inkberry Avenue, I ignore the breath-like huffs of the pump she’s squeezing in her pocket.

“What if he kills you?” she asks, shivering. “What if he’s a predator?”

We’ve been walking since before sunrise. Four hours ago, I was on the floor of the emergency room with tears and snot on my face, wailing “fix me” over and over. The nurse emerging from the bathroom didn’t know what to do with me. When he turned to pick up the intercom, I panicked, as if suddenly realizing where I was, the eyes that were about to be on me. I fled in the direction of my hotel.

I ran until my feet ached and only stopped moving when my phone vibrated on my hip. A bright blue notification from my dog-walking app—I had been hired by Petyr Ivanovska who lives about seven blocks east on Inkberry Avenue.

It’s a long, pebbled road walled in on either side by well-manicured gardens. On my left, goldenrod and witch hazel, like orange-yellow spiders, flourish in the shade of tall wooden fences. Trumpet honeysuckles, skinny and coral, resemble deflated versions of the balloons clowns twist up into animals. To my right, dewy-wet holly and wild strawberries cluster at the base of a cast stone birdbath.

I still feel raw, vulnerable to the world, but I haven’t cried for a few minutes now. My younger self looks in the water, pricking the pristine surface with a finger. The reflection of the mask ripples, stretches, and dances at uncanny angles.

When I get to where the fence ends, my legs ache. The cottage sits behind a white picket gate covered in holly. Even through the trees and shrubs, the place looks worth over a million with its three levels, rustic stone walls, and massive, steepled entrance covered in climbing ivy. It’s isolated, no noise from cars or people. Any neighbors must be hidden along Inkberry at least a mile down.

The doorbell is like a gong. I wait impatiently, ripping my nails with my teeth as my younger self watches the door.

“I bet he doesn’t even have a dog,” she says. “What if he’s gross? What if you bleed through your pants?”

“I won’t,” I say.

“What if?”

“We’re coming!” He sounds normal through the door. When it opens, the collie bursts out. She sniffs down my jeans while her tail thunks hard against the doorframe. The man steps out—mid-30s, messy blonde curls, brown eyes, trimmed beard. Caucasian cherub.

“Hi, hi,” he says, holding the leash. “Petyr. And she’s Circe.”

I get on my knees, shaking my hands in the collie’s mane. I notice he’s offering me the leash, but as I stand and wrap it in my hand, Circe’s snout is in my crotch.

“Molly, right?”

“Right,” I say.

Circe is insistent when it comes to exploring. Do I smell that bad? I ignore the judgmental stare of my younger self. She thinks I deserve this. Sometimes, I wonder if she knows we’re the same, and whatever happens to me is going to happen to her. She’s a little cunt, actually.

“Where is it you’re from again?”

“Complicated,” I say, turning my hips to avoid Circe’s nose. “My mother is from Uganda. My father was born Scottish but moved to London at fifteen. I was born in London, but we moved to America when I was three. And then back to Scotland two years ago. And then I came back here.”

Petyr pushes Circe’s head to the side, freeing me so I can tug her down the steps.

“So, you’re an American with an accent.”

I want to argue, American is an accent, but I’m thinking about how much I wish the sun would explode and swallow everything so that he’s not thinking about what my pussy might smell like.

“Your bio mentioned you’ve got a month here. Right?”

“For a film project,” I say. “Grad school.”

I don’t mention that I got ‘removed from the project’ three days ago by my classmates for being hysterical. I don’t mention that I screamed at them and threw things. They could have the movie, since the script wasn’t mine anyway. No one had been interested in my submission for the final project. My script was not funny enough, and it was too ambitious. But I was determined now to stay the month and do the project using my own screenplay, supported by people like Petyr and other monied dog-owners. Paying for the roundtrip flight was the only good thing my university ever did for me. I was not going to fly back early using my credit card. I was going to make my movie.

I don’t want to talk though. I just want to walk his dog. I think he senses that, because he nods and goes inside.

After walking Circe, I return to the cottage and relinquish the leash to Petyr at the bottom of the steps. He digs in his pocket and pulls out his phone. My app notifies me of a new transaction, and I feel guilty when I see the tip amount. He seems to notice my face and insists. Glancing at the size of his house, I slide my phone back in my pocket. It’s enough for basic props and a few buckets of fake blood.

*

With the money from Petyr, I get a cheap suit, a scarf, a gown, the blood, and food coloring (for the 32 drops of green that go into each gallon). Being back in my hotel room feels less like a failure when I’m dressed as someone else. In fact, it’s exciting.

For the first scene of my short film, I dress as The Woman, a succubus that walks the night, then preys on men who are awake in the early morning hours. Instead of men returning home from bars, their ankles crumbling under the weight of their drunken stupors, The Woman sees only flesh and the promise of meat, bone. She looks girlish, with long, soft hair and a cheeky smile. She has cat eyes now, because those are the only contact lenses I brought with me.

After fitting myself in the white velvet gown and applying the yellow contacts, I set up the tripod and camera. The shot is simple, but stunning. Slivers of light are being projected onto the sepia-toned wall from the blinds and the sheets are crumpled messily at one end of the bed.

Just before I sit on the bed to record, the room glows with the light from my cell phone. Fifteen missed calls from Kenneth. I don’t call him back, because he’s my father. I want to shake off his presence and be enveloped by the scene, but my eyes are wet and stinging. In costume, I sit on the bed, staring at the fuzzy blur of car lights through the window. My young self sits next to me, swinging her legs and bouncing her butt on the mattress.

When I stand up, a speckle of red is on the blankets. I go to the toilet and sit, yanking out the tampon to insert the new one. The first time I got my period, I thought I was dying and I told no one. My parents had never mentioned my ‘changing body’ before. Was it called a period because it was the end of something? The end of innocence?

Once you see blood, is that ‘it’?

*

When I pick up Circe the next morning, she leads me excitedly onto the avenue. I notice as we walk that Petyr is grabbing a wool pea coat from a hook behind his front door and, instead of getting into his car for work, he’s following us. I can’t help but look at my young self, confused.

“You don’t want me to walk her?” I ask.

“No, I do. Mind if I come along?”

I nod, not sure if I mind or not. Every few steps, Circe glances back at her master, awaiting his movements and commands. It’s sweet. And annoying. Because why the hell would he pay me to walk his dog when he can walk her his damn self?

“If you see any birds, you’ll want to grip the leash,” he says and pauses thoughtfully. “Your accent changes every few words, it seems like.”

“I didn’t say anything.”

“When you were talking yesterday, I noticed.”

“It depends who I’m talking to,” I say. “If I’m on the phone with my mother, I mimic her. I don’t know. I got a lot of it from movies, I think.”

“I know fuck all about movies. I don’t even own a TV. Not a working one, at least.”

“But you live in a house like that.”

“Like what?”

He sidesteps a bike rack, brushing a straw basket on one of the attached bicycles. I stop to let Circe pose among the bluets bunched in gray-blues and gray-purples at her feet, each one’s pale petals twitching around a burst of yellow at its center. Circe’s fur separates and wisps around her face, whipped by the wind.

“Ever seen a horror movie?” I ask. “Carrie? Night of the Comet? The Slumber Party Massacre?”

“No.”

“Slumber Party Massacre II?”

“Who likes getting scared? I mean, genuinely?” He seems perturbed as I start down the avenue again. “Oh. You do. I can tell.”

“I like movies.”

“They’re gratuitous.”

“I like when they’re gratuitous.”

“It’s just murder,” he says. “Naked women being chopped up.”

“It’s catharsis with blood and boobs. A lot of people like boobs.”

“That’s fair. I’ve heard of those people.”

“Why pretend we don’t think about sex and blood and all that?”

“I don’t know. To be a productive society, maybe?”

“I can’t be productive if I’m thinking about boobs?”

“I mean, I can’t.”

We walk another mile, saying nothing. It’s a comfortable silence. Petyr is warming his hands in his pants pockets. My younger self kicks pebbles down the road, sighing with boredom every few seconds. I breathe into my knitted scarf, smelling my mother, before we all turn around.

“Do you not have work today?” I ask, glancing at him.

“I know it’s weird to walk with you. To be honest, I don’t get to talk to a lot of people.”

“Is that why you hired a dog walker? For the talking?”

He shrugs. I suppose people with big houses tend to keep small circles. I wonder if he goes to therapy, or if he needs it.

“I stay in my office at work, stay in my room at home. Not much of a life, I think. But I keep on doing it every day.”

“You should get a hobby.”

“Like horror movies?”

“Whatever wakes you up.”

“I guess fear does that. Although, if you like being scared, that’s not real fear, is it?”

“Maybe not.”

“Then what scares you?”

It takes me a moment to notice my young self is tugging at the end of my scarf.

“Check your pants,” she says.

When Petyr gets ahead a few feet, I turn to check. No stains. I glare at my younger self, who makes a fart sound with her mouth behind the mask.

Resigned, I admit Petyr is nice to look at. At the very least, I prefer walking with him to my own company. Anything to draw me out of myself and into the fresh air. Then again, I’ve known myself for a long time. There’s only so much we can argue about anymore.

*

For six hours, I am locked in my hotel room poring over my script. I haven’t stopped since I got back from walking with Petyr. After a month of letting it sit in my backpack, scribbled over with notes from multi-colored pens, I run through with a red marker and check over the dialogue, making sure my newest revisions are consistent: two characters instead of four, both played by me, every shot in black and white.

We open on a split screen of The Man and The Woman, only one a monster but both monstrous. An establishing shot—The Man, drunk, leaves his favorite bar at the end of an alley. There is a sound of ripping flesh from the shadows. That sound continues when The Man exits the bar at sunrise and stumbles down the alley and offscreen.

The Man has narrowly missed fate. The Woman prowls, eats, enjoys.

Over and over, The Man frequents the bar, just out of The Woman’s reach. Every morning, The Woman devours another man with another secret. We aren’t sad, because their families are no worse without them. They are as absent dead as they were alive.

The music rises each time. It holds a high pitch as The Man finally stands in the alley, and his wife speaks offscreen. She begs for him to look at her. Just once, look at his children, be a father.

The Man turns into the bar. The Woman watches, waits, as the sound of the wife’s heels clicking on the pavement fades away.

When The Man leaves the bar again, he comes face to face with The Woman—the final moment. We flash between each of their faces. Fate finally catches up. Blood sprays.

My phone lights up, and I blink away the daydream. A text message from Mother.

Please call him!!!

She’s never understood my relationship with my father. I don’t think I ever understood hers either.

He was never involved with me like he was with my brothers. With them, he was overly bonded. They all turned out just like him: stoic, masculine, soulless. Knowing how warm they were when they were young, they might as well have died. I had to mourn them just the same, and so did Mother, even if she tried to hide it.

*

Walking to the cottage down Inkberry feels duller today, more one-note. I wonder if, a few days into this arrangement, there’s a possibility for sex. My younger self thinks I’m the only person in the world who’s bad at reading people, at sex. I like to think I’ve outgrown that idea and that she won’t glare at me while someone’s inside me like I’m doing something unnatural. But maybe she’s right. Maybe yesterday was a fluke and now, Petyr will be the faceless rich guy from the internet who wants a dog walker when he isn’t at home.

In front of the white-painted gate, beside his brick mailbox, he’s flicking through a stack of envelopes. In the yard, Circe is rolling through the grass, gathering burrs. It’s strange, almost creepy, and maybe charming that he’s at home again. I decide it’s nice, actually.

“Morning,” he says, waving me over. “Sleep okay?”

“I did.”

“No nightmares?”

“Aside from the one where I’m naked and chopped up, not really.”

“See?” He points at me with an envelope, making his face grave. “It’s all the blood and boobs. And you’re not even fazed. You’re desensitized. That’s the worst bit.”

With Circe, Petyr and I walk down Inkberry. He goes all two miles with me, where the avenue is interrupted by a busy street. He and I shoot the shit, avoiding topics like love, childhood, family, and the soul. Instead, we talk about the basket on the bicycle, now yellow with pollen. About his job as a computer technician. About Circe’s need to chase birds. About how Roger Ebert didn’t actually hate horror movies.

On the way back, when my finger is in my mouth, I realize my nails have grown. Did I not bite them yesterday?

He says goodbye casually. We are both in this routine together, and he is assuming I will be back tomorrow. I will be, but I don’t often meet people who think of a future with me in it.

I smile at him, but it’s fake. On the brink of leaving, I am suddenly thinking about the missed calls, then my childhood, and my mother’s blood. I look forward to seeing him tomorrow.

All of this happens every morning for almost a week.

*

I should be sleeping, but instead I sit in the bathtub with scissors in my hand, and I wonder if it’s worth it. Between two fingers, I stretch out the front portion of my hair. The blades hover near my forehead, but I can’t make myself do it.

Kenneth hasn’t called since yesterday, but I can’t stop thinking about him.

Everyone used to say I look just like my father. I would look in the mirror and see his nose, his chin, and his eyes on my face, and I’d fixate on it until all I could see was Kenneth. As a child, I thought it was strange but tolerable. When I was thirteen, after my mother slit her wrists in the kitchen, I let my nails grow out and bit them into points. When I was in front of my father, I’d claw at my face. The doctor said I was seeking attention, which I think should have been a sign to give me more of it. My father took it as me being hysterical and distanced himself even more. My mother, despite being loving, got so emotional I couldn’t take it. They started to tape up my fingers with duct tape to keep me from scratching.

One night, I went into my oldest brother’s room and put on the Ghostface mask I found in his closet. Kenneth threatened to put me in a box and send me away if I didn’t take it off, but by that age, I was wise enough to know he was a coward. I wore the mask to every event for months. Mother tried coaxing me out of it at first, but it got me to stop clawing, so she let it go. It didn’t come off until I got a therapist at sixteen.

My young self sits across from me in the bath, her tiny hands trembling around the blood pump. She knows I want to cut my hair to play the part of The Man in my film, but she won’t stop talking.

“You’ll look just like him,” she says.

“Shut the fuck up.”

“You’ve got his eyes, and his nose, and his chin, and you don’t feel anything.”

I put pressure on the scissors. The blades force their way through, and the hair falls and floats down, dark and curled on the white porcelain between us. I take another piece and cut, then another. The hairs, finally freed, tickle the goosebumps on my naked thighs.

“Fucking stupid,” she tells me.

*

On the eighth day of knowing Petyr, I explain my haircut to him. For some reason, I feel the need to be ashamed.

“I’ve been working on a short film,” I say.

He nods, as if intrigued. I’ve run out of outfits to wear on our walks, but I try to mix and match what I have stuffed in my suitcase at the hotel. Petyr seems to have an endless array of beautiful coats, sweaters, and button-downs, all of which complement the beard he is growing and maintaining on his jaw.

“My guess is… comedy?” he says, snapping his fingers.

“Gratuitous fuckery and violence.”

He feigns surprise.

“Well, what’s it about?”

“A succubus,” I finally say. “And a man. I play both parts…”

“But what’s the story? What’s its reason for existing?”

I toy with the idea of talking about my past. My chest hurts.

“You’ll never watch it anyway.”

“Why not?”

“You don’t have a TV.”

“I have a friend with a damn good camera,” he says. “I think he worked in commercials. I could pass your name along?”

“Is he rich like you?”

Petyr chuckles, unoffended by everything. “If I’m rich, sure.”

“Are you a trust fund baby?”

“When my uncle died, he left me the house. Not much intrigue, I’m sorry to say.”

“I don’t know. You could have a wife or two hidden away in there.”

My younger self leaps out from behind Petyr, almost making me jump. She always follows closely behind us, but some mornings, like today, I forget her.

“I’ve got to tell you something cool,” Petyr says suddenly. It sounds like he’s been thinking about it. I realize with this change of subject that we might be breaching new territory, maybe a new relationship. “I’m related to Shakespeare on my mom’s side. I’ve got a painting of him in my foyer.” He looks at me seriously. “I’m not kidding.”

I don’t know if my urge to laugh is from my doubt, the fact that he thinks this is an acceptable explanation, or the fact that I want to believe him anyway. I still don’t quite know when he’s joking.

“You’re sure?”

“I’ve got records and everything.”

“I believe you.”

Petyr smiles to himself, looking content as we approach the house. He unlocks the front door, letting Circe inside, but the door is half-open behind him as he stands in front of me and fiddles with his key ring.

“We can go inside?” he says.

“It feels nice out here, actually.”

He nods. Then he snaps his fingers, as if with an idea. His hand rests on my arm, brief but not brief enough to be nothing, before he steps into the foyer. I hear him greet Circe as the door shuts behind him.

My younger self kicks the bottom step over and over. She hasn’t taken her mask off in years. Some days, I hate to admit, it makes me sad. All I know of her anymore is the ghostly face wet with Red 40 dye and the soft thump-and-fizzle sounds she makes by squeezing the pump in her hand.

“He’s not gonna have sex with you now,” she says. “He gave you the in. You didn’t wanna do it, coward.”

I start down the steps to walk back to the hotel, but the door opens. Petyr has shed his coat. He has a backpack on his shoulder with a bottle of wine in one hand and two glasses balanced in the other. He sets the bottle on the stone and unfolds a tiny corkscrew from his keychain.

“Do you drink?” he asks. I nod as Petyr yanks out the cork and fills each glass halfway.

We walk down the avenue, taking our time. About half a mile down the road, Petyr points out a cluster of holly, which hides a wooden bench shaded from the sun by two fenced-in trees. He sets the backpack containing the wine bottle on the grass. Sitting this close to him, I smell cologne and pine and a hint of sweet honey.

“Your cheeks are red,” he says. The brown of his eyes looks more amber in this light. “I hope I’m not making you nervous.”

I want to make a joke. Instead, I’m honest. “I’ll get through it.”

My younger self tosses rocks over the fence on the other side of the avenue. The sound distracts me, but I force myself to keep eye contact with Petyr. We sit in silence, listening to the sudden birdie-birdie-birdie call of a cardinal somewhere in the thicket. I feel the wine becoming a reason for me to say what I’m thinking. The more I’m truthful, the more my younger self seems to fade away, or at least gets easier to ignore.

“I’m not good at this,” I mumble.

“What’s ‘this’?”

“I mean, I’m not good with sex.”

“Like, you’re not okay with it?”

“No, I’m not good. At. It.”

“Ah.”

“How many people have you been with?” I ask.

Petyr shrugs. “I could fill a church.”

“Yeah?”

“It’s just something. I’m not really proud of it, but I’m not ashamed of it.”

“I had a boyfriend in high school who called his dick the Jawbreaker.”

“Are you saying that’s why you’re not good at sex?”

“I’m just saying it’s pretty funny.”

As Petyr pours a second glass, I look in mine and pick out a spikelet of witch hazel. He stops talking, opting for quick, big gulps. I realize he thinks he needs the drink. Maybe he does.

A red cardinal flutters and lands on the edge of the birdbath. The crest on his head tilts in the wind. My young self approaches it, close enough to touch its wing. At that age, I was curious why the females were less beautiful than the males. But what makes the color red so beautiful? What makes it masculine? I know now it all means nothing, and the cardinals that are red just happen to be male, and I can still be red if I want to.

After Petyr’s second glass, I see his movements slowing. Still, I pick mine up from where I set it in the grass and offer it.

“Getting me drunk is naughty, naughty,” he says. Still, he takes it.

“You seem like you want to get a little wasted.”

“I don’t usually drink like this. For Circe.” He says it matter-of-factly but gulps down the rest, then hands me the glass again. “You’re gorgeous.”

“It’s weird you waited until you were drunk to say that.”

“If anything, my mind’s much clearer.” He swirls his fingers over his temples. “You’re right. I’m done pretending I don’t think about boobs.”

I smile, watching him slump back to watch the graying sky above. He swallows hard enough that his Adam’s apple jumps.

“Just relax,” I say. I lean back too, like I’ve known him longer than I have. “I’ll be here.”

*

The sun is leaving fast, and the air is cool. The bottle is empty. So are the glasses.

Petyr leans against me as we walk back to the cottage. His backpack dangles on my back as I use all of my weight to keep us steady, and even then, it isn’t quite enough.

“Petyr, you’re going down,” I say.

“What?”

He starts crumbling, so I bend my knees, letting him slowly down on the grass to prevent a violent fall. Still, his butt hits the ground hard. He rocks a little.

“I’m gonna teach you how to fuck,” he says, eyes half-lidded as he nods to himself.

I smile despite myself, holding his biceps to keep him sitting. “Maybe when you’re sober.”

His hands explore my hair, ruffling and mashing it against my face, and brush my nose and eyelashes. I sniff hard into his hands. He chuckles, clumsily taking my forearms as he falls backward, pulling me down in a loose hug. As he starts to breathe steadily with sleep, I breathe in, forgetting for a moment about the mask, the movie, the inevitability of death.

*

The next morning, in the hotel parking lot, I mount the camera on the tripod. My cropped hair is matted, and my suit has been drenched in fake blood for the second part of my movie’s climactic scene, where The Man and The Woman finally meet.

The rising sun makes everything orange. As I turn the camera on, I notice my reflection on the screen, the short hair and my father’s chin. When I think of my father, I think of the blood. I was twelve when I got home from school and found my mother on the kitchen floor. At first, there was so much blood, I didn’t know where she was hurt, but as she reached for me, I saw it was her wrists. I remember the nausea, my vision rushing sideways as her wet hands ran slick down my face.