INTERVIEW WITH Christian Kiefer

Christian Kiefer is the director of the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at Ashland University and is the author of The Infinite Tides (Bloomsbury), The Animals (W.W. Norton), One Day Soon Time Will Have No Place Left to Hide (Nouvella Books), and Phantoms (Liveright/W.W. Norton). Photo by Christophe Chammartin.

FWR: Let’s start with your pieces for Literary Hub, where you focus on grammar as craft. Of Lauren Groff’s writing, you say, “The style of her sentences … are the gears and wheels of her genius.” Often, when we talk about craft, we’re looking at aspects of the form—point of view, exposition, characterization. I found it interesting how you articulated conditioning these components with the shape of prose itself. How does a writer go about using language and grammar to achieve a desired composite effect?

Christian Kiefer: I think the easy answer here is by consciously reading with language and musicality in mind. For me, the sentence length is effectively the length of breath that any piece of writing asks for. That length of breath can fluctuate depending on the scene or situation, but the exhale/inhale of a line of text is mostly dictated by its rhythm and its use of pauses and end stops (commas, periods—but also textual interruptions and so on). With someone like Faulkner, you’ve got an increasingly ostentatious use of clauses and phrases meant to contribute to the flow of the text so that the length of breath becomes almost laughable. For someone like Groff, you’ve got shorter, impactful clauses often fraught with a staccato rhythm that, even when rendered by soft syllabic information, is nonetheless possessive of a kind of wave-like feeling. One doesn’t even notice the periods, the commas, because the unit of rhythm is rendered so expertly.

There’s a whole list of “grammar rules” out there on the internet, of course, and once you have those under your belt, it’s pretty easy to see when people consciously break them. James Baldwin, for example, has a deep love of comma splices, which many college professors would mark as incorrect. Or Garth Greenwell’s idiosyncratic but deeply meaningful use of semicolons. Look at the rhythm of Jesmyn Ward’s prose, or ZZ Packer’s, or Michael Ondaatje’s. These are masters in how they employ grammar as a tool of meaning-making.

FWR: You’ve mentioned in interviews that when you’re writing poetry, you don’t think about narrative, yet the sentences in your novels are so poetic, such as this passage from The Animals:

Above him, above them all, the sky had gone full dark and stars seemed all at once to rise from the tops of the trees, their pinpoints wheeling for a moment across that black expanse only to return once again to those needled shapes, as if each light had come up through the soil, through the epidermis of root hairs and into the cortex and the endodermis and up at last through open xylem, the sapwood, through the vessels and tracheids, rising in the end to the thin sharp needles and releasing, finally, a single dim point of light into the thin dark air only to pull one back from that scattering of stars, the cambium pressing down the trunk, pressing back to black earth. Time circling in the soil and the silver tipped needles. Time circling in the big sage and cheatgrass of everything to come before.

The first sentence is a kind of blazon of a conifer, used less for exposition and more as movement. You’ve mentioned considering velocity as a specific approach to writing. How do you see poetic language as capable of creating certain motion? And in that way, how can lyricism serve narrative?

Kiefer: You’ve happened upon a great peeve of mine: style guides dictate prose should strive for clarity, as if poetry is the only form of writing that gets to be poetic. On one hand, that passage you quoted is perfectly clear to a plant biologist, although of course I’ve taken some license here and there, but its point and purpose is to sink the reader into the language of the natural world, a significant and meaningful (I hope!) theme of the novel.

The motion of the above passage is paused-for-breath by the commas, allowing for a lilting rhythm. I hone this by reading passages aloud over and over and tinkering with the rhythm and the language until it feels representative of whatever effect I’m trying to work toward. Sometimes it’s very, very conscious and sometimes it’s more intuitive, but most often somewhere in between the two.

Those last two sentences above are summatory of the long sentence that precedes them. It’s a way to nail down what might be to an average reader just a bunch of nonsense. I’m offering a way to anchor the reader to something a bit more grounded, though still representative of what the passage is “about”.

This is all to say that in terms of velocity something needs to be moving forward in the text. I’m a pretty patient reader but if there’s no apparent motion, I will eventually get bored. The writer has to put pressure on something—maybe it’s on the sentences themselves, but often it’s the characters, the situation, the scene. Hemingway is known for these short(ish), punchy sentences, but when in action scenes like the end of “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” he moves into a completely different rhythm, a completely different velocity

FWR: Your fiction heavily employs atmosphere. In your essay on Garth Greenwell, you call one of his passages a “stuttering delay on the details of the protagonist’s recollection and remembrance.” This relationship between the information released in each clause and what is concealed, to be released later, is a playful manipulation that lends itself to building the haunting atmospheric elements in The Animals, too. How do your terms “re-grammaring” and “re-informing” apply to your approach toward writing and establishing atmosphere?

Kiefer: This is probably something I learned from Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! Faulkner gives the reader so much information right from the first couple pages, yet the reader is totally flummoxed as to what is happening. Even at a basic level, the reader can hardly situate herself in the text. An elderly woman is sitting in a room telling a disjointed story to a college-aged Quentin Compson (from The Sound and the Fury). It seems like it would be straightforward, but part of Faulkner’s interest is the assumptions made by survivors of the Old South, such that most everyone knows the same characters and situations, and so Rosa Coldfield’s narrative—a narrative later assumed by Quentin’s father and by Quentin himself—is therefore fraught with assumptions about the knowledge of the listener/reader.

What this all amounts to is a text of accretion, the meaning of which deepens in spite of (or perhaps even because of) the reader’s confusion. It’s a miraculous thing and an almost impossible book to read, let alone write. I think I’ve probably read it ten times or so.

Having said that, I do think it can be very problematic to willfully withhold information from the reader, especially basic information. For those of us who are not Faulkner—and even Faulkner is not always in full possession of his talent—it’s important to set the reader into a situation or scene that is apprehensible. It can be terribly frustrating to read something and have to struggle to locate basic information. Absalom, Absalom! works counter to this because it’s very much about the act of storytelling over the gigantic canvas of history.

And thank you for your note on my use of atmosphere in my writing. It’s the part of the work that I most enjoy, which mostly comes late in the revision process. I’m doing 30 – 40 drafts of my writing, generally speaking, and a lot of that is dialing in specific textual effects and making sure that the setting is solid enough to be imagined but gauzy enough that the reader can also imagine her own version of it. In this sense, concealment can allow the reader into the text. In The Animals, I want readers to be able to envision the Nevada desert, but I also want to make sure it’s their own Nevada desert, not necessarily mine.

FWR: In Phantoms, characters and events parallel each other throughout, whether John Frazier and Ray Takahashi’s experiences in their respective wars, or John’s attempt to unravel the story of Ray against the backdrop of the town’s desire to deny it. Your syntax often mirrors this parallelism, as John views himself in opposition to or in league with different characters. Can you talk about how prose can embody what it is in fact describing, and how the goings on of a story might be inspired by its prose? How would you advise writers to play around with the tension and congruence between prose and content?

Kiefer: I would advise writers to play around with everything. In terms of the specific question, there’s a balance needed that is embodied in the syntax itself. Whenever you veer from the arrow of the narrative, you’ve got to remember that the reader is likely waiting for the text to reconnect with that (perceived) forward motion. As a microcosm, consider an individual sentence. “Once he awoke from his nap, Bob, still hung over from the night before—that last flight of whiskeys had clearly been a terrible mistake—returned to the office.” So what’s happening there is you’ve delayed the subject’s sentence by 7 syllables, then provided the subject, Bob, which immediately sets up the reader’s expectation that the verb is coming, which you’ve then delayed again by 25 syllables. You’ve got to make sure you’re deferring the reader’s grammatical satisfaction for a good reason. Too much of that will come off as an affectation. (Late Henry James is really, really good at this kind of thing.)

On the other hand, if you’re dealing with a scene where the protagonist is trying to avoid talking (or even thinking) about something, then the syntax—even in exposition—might start wrapping itself in circles in order to display something regarding that state of mind, delaying and interrupting, and so on, so that the reader can feel the reticence and avoidance without you having to state it. That’s a fine line to walk because it’s so easy to overdo.

FWR: You play around often with point of view, too. In The Animals, Nat’s perspective is in second person, and you write from the perspective of Majer, who’s a bear. Both Phantoms and One Day Soon Time Will Have No Place Left to Hide feature first-person plural, which in the former creates tension between community and individual and in the latter calls attention to the (inter)viewer and the nature of an artistic lens. What is point of view’s role in situating a reader closer to or farther from the text or characters?

Kiefer: This is something I’ve thought about a great deal. Pam Houston is the master of the second-person narrative, so I’m certain I learned everything I know about that from reading her work. Going back to Faulkner: he employs first-person plural often (look at “A Rose for Emily,” for example). Point of view is, for me, a decision of where to place what John Dos Passos famously called the “camera eye.” That placement can be very idiosyncratic and can even be off-putting (I remember Tin House-editor Rob Spillman commenting that he generally finds second person difficult to pull off).

What I’m interested in is using point of view to shift the position of the reader vis-à-vis the narrative. If we move from standard third-person past to second-person present, that does something significant to the flow of the text and the reader’s position to that text. The reader has to recalibrate where he thinks he is in relation to the story, which I find wonderfully invigorating (as a reader). Ondaatje does this kind of thing with scene, situation, character, and time when he shifts us into some other point in the timeline or shifting the entire narrative as in Divisadero. It’s a way to force readers to reapply themselves to the text while questioning what narrative is and what it can be.

FWR: I want to talk more about the filmic nature of your writing. One Day Soon Time Will Have No Place Left to Hide is described as a kinoroman, or a cinematic novel, and within it the narration functions at once as camera, us as collective readers and viewers, and words, as this is, of course, a book:

When she moves away we do not follow but watch her, receding, pulling out of focus as she reaches the glass doors of the casino, the reflection of the parking lot shifting momentarily across her disappearing shape. In that reflection is all of Nevada. In that reflection is you, reading these words.

Soon after, we read “We have not seen her smoke before, but she is smoking now.” This conflation of a literary feature like backstory with a note I’d expect to read in a screenplay functions as a sort of formal synesthesia. How do you draw from other creative formats in your work? And in your mind, what even is the role of form when it comes to writing?

Kiefer: I think it’s important to occupy “the arts” in a deep and meaningful way and to make sure you’re exploring how the effect of one work might be achieved in another. Like how might one create the textural quality of Anselm Kiefer’s (no relation) The Orders of the Night with words? Or the hauntingly floating opening of Hans Abrahamsen’s opera Let Me Tell You. Or Kehinde Wiley’s official portrait of President Barack Obama. That portrait makes me tear up. How could I as a writer accomplish the way it does that?

Obviously these are shifty questions. Kehinde Wiley’s portrait is wonderful because it can’t really be accomplished any other way, but I do think it’s useful to consider artistic borrowing in this capacity. After all, one isn’t trying to replicate the actual painting or music or text or film or whatever it is, but rather the feeling of that form.

FWR: John states early in Phantoms that “much of which [has written about Vietnam] helped [him] understand what happened over there and how the heavy stone of that experience continues to ripple out over a life that has been, at times, troubled by its own hidden currents.” This understanding of the Vietnam War helps the reader understand the domestic violence between the white and Japanese-American families of Newcastle as “a legacy of sanctioned violence both subtle and overt.” The formal can be of course akin to the traditional. So how can writers use formal conventions in a way that allows us to also re-understand and re-experience them?

Kiefer: At heart, I’m a traditional narrative novelist. The formal conventions are there because they work, but their existence also allows us to push against them, sometimes pretty hard, which is to say one can break herself upon the rocks of formal conventions. Despite the violence of that metaphor, I actually mean it to be positive: breaking in the sense of breaking open.

One of the things that formal conventions made possible in Phantoms was the direct critique of whiteness. A certain kind of America loves its nostalgia, but nostalgia for, say, the 1950s, a nostalgia that is also pre-civil rights, which is to say nostalgia (and especially nostalgia) can become a tool of white supremacy. So I’m writing about the Japanese internment and the American war in Vietnam, all of which is held in a traditional structure strong enough to push against—both in terms of the structure (which does shift and turn from time to time) and the themes.

FWR: Kirkus Reviews describes One Day Soon as an ars poetica, and your reflections on the creative process are refracted in the many ways in which you participate as a writer, musician, educator, and editor. Similarly, your writing encapsulates your interests, from being an ardent nature lover to having studied film at USC. Does writing have a requirement to in some way reflect on itself as a form of expression? And what then is the role of the author to do the same?

Kiefer: I’m not entirely certain how useful it is for writing to comment on writing. I don’t, for example, find traditional “craft” books to be very useful, nor do I much enjoy books that swing toward self-reference or meta-textuality. I already know I’m reading a book, so pointing out that I’m reading a book isn’t of much value to me. On the other hand, I love Italo Calvino so maybe I’m full of shit on this.

I think more important is being open to the truth that there may be no requirements in writing at all. Blake Butler, Katherine Standefer, Tasmyn Muir, Sally Rooney, Rebecca Makkai, Matthew Salesses, Emily Nemens: these are all wonderful writers who are doing very, very different things with words all while fulfilling whatever “requirements” we might place on them (or that they might place on themselves). What I want, what I long for, is a full immersion of my heart in the deep red-hot center of the text. I’m in the business of breaking hearts. We all are. And to be broken in turn.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a multimedia artist, poet, and writer. Griffiths is the author of Miracle Arrhythmia (Willow Books 2010), The Requited Distance (The Sheep Meadow Press 2011), Mule & Pear (New Issues Poetry & Prose 2011), which was selected for the 2012 Inaugural Poetry Award by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, and Lighting the Shadow (Four Way Books 2015), which was a finalist for the 2015 Balcones Poetry Prize and the 2016 Phillis Wheatley Book Award in Poetry. Her most recent book, Seeing the Body, is a hybrid of poetry and photography (W.W. Norton and Company).

FWR: I’d like to start with the titular poem, “Seeing the Body”. In it, you write into grief and how that grief can bifurcate the life of the living. In your visualization of grief, you create imagery (such as “flowers/falling from her blood” and “bale of grief on my back, opening/ into something black I wear”) that seems resistant to more common depictions of grief. (I’m thinking of poems like Auden’s “Funeral Blues” or the gothic imagery of Edgar Allen Poe, which have become synonymous with writing about loss). Did you find yourself resisting cliche, or writing through images that you had read from others, when you first began these poems?

Rachel Eliza Griffiths: The engine of “Seeing the Body” relies on how breathing happens through a poem as much as it is also about how breath stops or is altered by grief. There is the involuntary tension of trying to sustain an image or to construct a narrative about a beloved’s life or one’s self, only to find all is ruptured.

Auden’s wonderful poem is after something very different than “Seeing the Body” insomuch as Auden’s poem calls for a moment of silence that feels quite public in its address of ordinary life. My own poem wants intimacy, to address the earth and the private echo of silence where there is the sense of falling through one’s body, one’s birth and death through the body of the mother. My mother. This poem hurt me the entire time I worked on it. Years. I’ve never been attracted to clichés, visually or otherwise, so I don’t think about resisting them. What has startled and provoked me is the immediate emotional connection I feel wherever I share these poems. I’m writing about a “common” experience yet it is anything but common for me.

I can never read this poem as it should be read. That was intentional. Each time I enter the earth of this poem I am further away from its original grief. I am somewhere else in my body and can’t get back to the woman who braced herself against the initial impact of loss. Whenever anyone experiences this poem I hope there is an intimacy of reading that does not exclude our bodies. Through language, I’m aware of forcing myself to stop in the middle of something that has neither beginning nor end.

Listen to “Seeing the Body” read by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: Seeing the Body includes a section (“daughter: lyric: landscape”) composed of your photography, which is alluded to in other poems (“For years I photographed myself/ in a white dress”, from “Husband”). You write in your Author’s Note that these photos serve “as a map of the self and of the greater world in which [you] are both visualized and invisible”. Had you planned on incorporating photography from the beginning, or how did that process develop?

Griffiths: In the beginning, I didn’t plan to use any images at all in the book except I began to think about the types of photographs I had created in Mississippi just before she died. I had to go back and consider what I was “making” when I was unmade by her death. Then I also remembered the deliberate focus I gave photography immediately after her death. I clung to the machine, my camera, like a life raft. I began to perceive my own body as an urgent conduit of my grief, which meant I couldn’t leave my body outside of any landscape on the page.

Perhaps the only way now that I can truly see my mother’s body again is through studying my own. This time was weird and messy because I couldn’t read books. I had a hard time using my camera. All these tools were nothing to me. When I began to write about my mother, it was very difficult because it felt like language was forcing me to accept elements of her death I couldn’t bear.

Perhaps the only way now that I can truly see my mother’s body again is through studying my own.

FWR: Did this impact your understanding of or play with syntax? (I’m thinking here of the poems “As” and “Good Questions”).

Griffiths: “As” and “Good Questions” are fragmentary or function as what I might call a “collage of the lyric” — the rhythm and imagery bleed together in an attempt to both isolate language and to hold the visible language intact as grief itself opens through the body of the page. Photographs offered me a way to be grounded in the world, to remember there had been a world I loved before her death and that I could and must return to it. Finally, it was transformative, after so many years of being diligent that these mediums lived in separation, to ask them to touch each other and hold me.

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: “Color Theory and Praxis (I)” is a poem concerned with the body, but also the body in art. Specifically, it considers the painting “Open Casket” by Dana Schutz, which depicts Emmett Till. The poem questions who has the right to the body, particularly a body of color, and after death. I wonder if this influenced your own writing, as some of your poems see you imagining the voice of your mother, as in “Comedy”: ‘Yeah don’t go and write about me like that/ she says. I already know you will.’

Griffiths: I’m ambivalent about my relationship to placing myself inside the voices and bodies of others. I’ve done it, whether by persona or in certain photographic series, and it can feel tense for me. Issues of permission and imagination fascinate me. I’m not interested in policing anyone but I do have the right to challenge, to question, and to critique certain things, especially when it comes to visual arts and representation. There is a lot at stake for me even when it feels like people want artists to shut up when their work is confrontational. I read an interview where Schutz said the painting was about a conversation with Till’s mother. I disagreed with her perspective and the “terms” of this unreal, fantastical conversation, which placed the mutilated body of a black mother’s son as its focal point, as its medium. There is a photograph of Mamie Till at her son’s casket. I don’t feel like Schutz’s painting could ever listen to, or tell Mamie Till’s truth. The artist has a right to do whatever she wants but I tried to understand what and where that right was located. I mean, there’s a painting of hers that features Michael Jackson’s body on an autopsy table. Again, do what you want but do it well. Also, I noticed she didn’t use Trayvon Martin’s image, or Sean Bell’s, Tamir Rice’s, or Eric Garner’s, or Jordan Davis’, or Philando Castile’s, or Mike Brown’s, or Ahmaud Arbery’s, or…or…

I’m tired. There isn’t enough canvas, enough pigment, enough bones in this country for black artists to address the violence and harm done to our bodies, our communities, by the imaginations or institutions that can’t bear for us to live. It isn’t our job or our art’s job to do that work either. Why is America afraid that we dare to imagine ourselves as anything but dead?

My mother and I would go back and forth about my writing. Sometimes she’d ask me when I was going to write her story. Other times she worried about my imagination. None of the poems in “Seeing the Body” ever enter my mother’s body and use her voice. I never wanted to do that. The dialogue in “Comedy” was exactly what she said.

It isn’t our job or our art’s job to do that work either. Why is America afraid that we dare to imagine ourselves as anything but dead?

FWR: In “Good Questions”, you write, “when did the final arrangements begin? / At her birth. Inside of wet rock. When my birth began.” Throughout the text, I was struck by your exploration of inheritance, whether of womanhood or illness, and how grief lives in the body (as in “Signs”). Would you speak to the development of this thread?

Griffiths: I’m in a more explicit stage of my life where I want to think of myself within a greater dimension, in conversation with beings that arrived before me, and those who are already arriving after me. I think about what I can share with the living and the dead. I’m constantly aware that the earth is different in her temperament since I was born. I’ve been astonished by how quickly some of our geographies have reverted and have healed during the pandemic without the presence of human abuse.

At this point, my work lends me an expansive way to think about how I might, as an artist, establish or assert my own lineage or claim inheritance in ways that don’t necessarily include children. I’m constantly thinking about how remarkable it is to begin to really take into consideration the manners, culture, trauma, resilience, joys, and ways-of-being that I have inherited. These things I hold have come from my family but they have come from a larger consciousness. They also come from within me.

I’m in a more explicit stage of my life where I want to think of myself within a greater dimension, in conversation with beings that arrived before me, and those who are already arriving after me. I think about what I can share with the living and the dead. I’m constantly aware that the earth is different in her temperament since I was born.

FWR: Seeing the Body explores the shifting ownership of the female body and how language can free, as well as constrain. In “Ars Poetica”, you write of imagining becoming a writer or a woman like your mother, before the neighbor and his friend interrupt your daydream: “his friend braked hard,/ barking like a dog… Hey, Bitch, he said”. In “My Rapes” your mother asks, “why/ I listened to white girl shit. How could alternative music/ hear a black cry like mine?” Can language free us from the body?

Griffiths: It depends on so many things – whose language, which bodies, whose freedom, whose history, or memory. “Ars Poetica” speaks about some of the ways that violence can interrupt one’s dreams or one’s work. The poem is also asking questions about how we, especially black women, can afford our dreams and our work. How the world consistently fails to appraise our contributions even while our bodies and cultures will be taken as commodities, as resources. The second poem you mentioned is about some of the ways your own family will refuse to allow you (and by extension, your body) to live in songs (and bodies) that they believe are dangerous. I listened to a lot of Tori Amos because of what had happened to me. I listened to Fiona Apple, Ani DiFranco. I listened to them because my mother wouldn’t hear my truth. She couldn’t bear the thought of violation because she loved me so much.

Courtesy of Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Listen to “Arch of Hysteria, Or, the Spider-Mother

Becomes A Woman” read by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

FWR: Building off of that question, you thread myth through your poems. For me, the inclusion of Athena, Arachne and Eurydice roots your experiences in grief and voicelessness within a larger historical and human story of being a woman. And the poem “Myth” speaks of “the literature/ of blood the black face gasps in air. No… / the black boy’s face merely insists/ it is a face to begin with”, which, to me, seems reminiscent of the commodification of bodies of color not only in commerce, but also in art. Can you talk a bit about the inclusion of these figures?

Griffiths: This question feels similar to the earlier question about Till. In some parts of the book, I found myself returning to stories about daughters who were powerful but seemed unable to overcome their roles in a larger “myth” or story. These stories would often place women inside of cruelty and violence – rapes, murders, or “transformations” that altered or punished their bodies, or drove them mad. The poem “Myth” is about my rage as well as my grief that murders of black men persist in a cycle that renders them faceless, whether that is through death or incarceration. And there is a spectrum of micro-massacres between those extremes. Their humanity is erased.

FWR: Were there poets or writers you turned to for guidance as you wrote through your grief? (Lucille Clifton’s “oh antic god” springs to mind). Or, are there poets or poems you love to teach or share?

Griffiths: Yes, I return often to Ai and Lucille Clifton! I’m thrilled at the forthcoming publication of a selected, How to Carry Water (BOA Editions Ltd.), edited by my dear sister, Aracelis Girmay. It will be a feast! When my mother died, Aracelis shared a poem with me by Joy Harjo, our current National Poet Laureate. It’s called “Remember” and I read it aloud often. If I were brave enough to get a tattoo it would feature lines from this poem.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

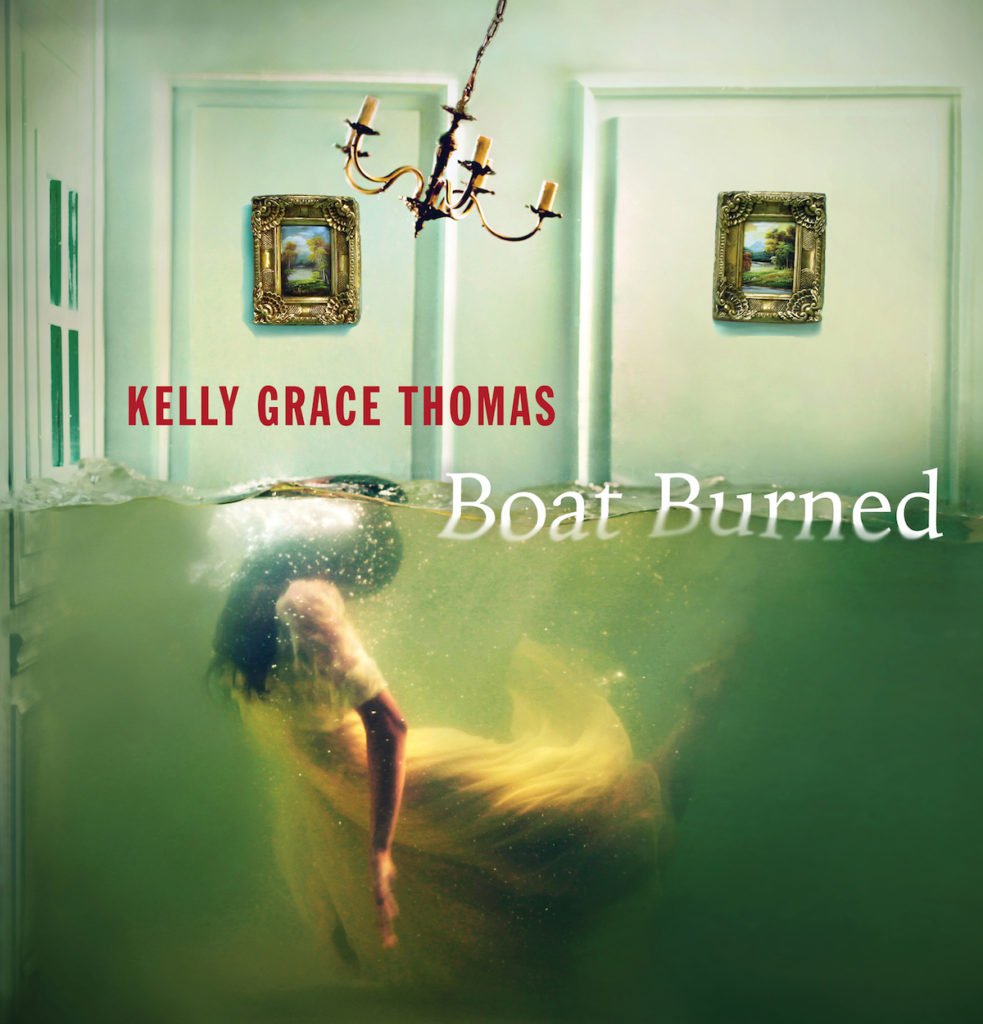

INTERVIEW WITH Kelly Grace Thomas

FWR: To start, I want to give you an image of my reading of Boat Burned. I was getting a pedicure and reading. I think part of what had me so enraptured in your writing in that moment was that I was already in a place where I was thinking about my body, and the relationship it has with the world, as someone was very physically touching my body. It created a very visible power difference between us, as he sat and touched my feet, in addition to a racial difference, a class difference and a gender difference, and I feel that these are layers that you explore and speak to in Boat Burned.

I saw in an interview with Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach, you had talked about your love of metaphor and the body as metaphor. I don’t want you to feel as if you have to repeat that conversation, but I did want to ask how you opened yourself up to writing about the body and the body in all of these different circumstances that threads through the book.

Kelly Grace Thomas: I think that at first it came from necessity. I can’t remember a time after the age of seven when I did not have a complicated, if not contentious, relationship with my body. I think that body image is the silent insecurity that no one really talks about, yet it’s a problem that we see in almost all women, as 25% of women have an eating disorder or experience disordered eating in some way. I think that growing up, I had this behavior that was modeled for me, and of course when you have a mother who has body image issues, you internalize that shame because her body gave you your body. I started to dig deep, in my poetry, and I realized most of the things that make me the woman I am– my body, how it looks, how it functions, all of these things– sprang from a source of shame. I decided I wanted to explore that.

I was in a Korean spa in Los Angeles. All the ladies were naked, and I felt so uncomfortable. I remember thinking, “I am so ashamed to be naked in front of these people”. It felt so vulnerable, and I thought, “you have to find a way to talk about this.” I sat down, and I thought, “if I’m not a human, what would I be?” And then I had the immediate thought, “I’d be a boat”. I wrote the poem, “The Boat of My Body” and once I had this metaphor, I felt like I had a mediator to have a conversation with my body that I hadn’t had before. It had been too close, and too painful, to touch, but once I had this metaphor that I could lean on to interpret these things or filter them, then I had a way to open up the conversation.

I feel like it’s a civil war sometimes, this idea that the mind and the body, or the soul and the body, became two separate things. I wanted to work on healing that in some aspect, and I think the metaphor helped. Once I started thinking about the body, then the layers came. I began thinking, “where did I learn this behavior? Why do I believe this? How does my body compare to other bodies? How does my body compare to others of different age, gender or background?”

FWR: Springing from the idea of that civil war and that experience of learning shame, reading Boat Burned, I was stopped again and again by your description of the inheritance of bodily dissatisfaction or trauma, which threads poems from “How the Body is Passed Down” (“My mother was still hungry. Royal/ with fridge glow. Learned/ that loneliness/ eats with its hands”) to “I Try on My First One Piece in the Dressing Room at Ross” (“My trunk is thick. / I don’t look/ expensive.”).

And as I started following this little bit of water, I realized, “there’s a river here. No wait, there’s an ocean here.”

KGT: I think growing up, I learned shame about my body, especially with regards to its relationship to men and being an object of desire. Once I began exploring this in my poetry, I found that this ran deeper than I ever realized. And as I started following this little bit of water, I realized, “there’s a river here. No wait, there’s an ocean here.”

FWR: I’m thinking of the line you have of the body as “monstered/ or womaned” (from “We Know Monsters By Their Teeth”), when you think of the body as a tool, it creates a separation so that you can’t judge it. I think what makes the metaphor of a boat so apt is that as a woman, your body is supposed to do all of these things. It’s supposed to mother, to carry, to nurture, and to charge ahead so that others can follow in the wake–

KGT: And still be tender, and still be sexy. It’s such a contradiction. As a poet, I think you’re an observer. For me, as a poet, you’re listening and watching all the time. I’m also an empath, so I’m feeling all the time. I can walk into a room and feel the sadness of the women. I was very much raised in a matriarchy, by these astonishing, powerful women who were on their own. I constantly saw themselves reaching outside themselves for power. I think so much of that goes back to someone telling them that, “your body is meant to do X, or supposed to do X”. I think that if gender is a performance, there is no bigger performance than a woman’s body, sadly, in terms of what the audience expects it to do.

For me, I became the audience and the performer. I was critical of myself, because I bought into this idea of what a woman’s body was meant to do to be tolerable for society. It’s so interesting that women are looked at for the function of their bodies, and men are looked at for the function of how they provide. The message is that our bodies are our skills, and if our bodies are not skilled in the ways that others want, they can be conceived as broken.

FWR: Exactly. And staying with the metaphor of woman as a boat, just a bit longer, is such a profound metaphor for you because it speaks to the different roles of a woman, but also ties in the personal significance that the ocean and boats have had for your family.

KGT: I grew up racing sailboats. My mom and dad grew up on sailboats. When I was ten, my dad went bankrupt and our family lost everything. The IRS took everything but his boat. My parents were already separated at the time, but we spent Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays with my dad. On Sundays, we would sail together as a family. So when my father said that he was going to move to Florida to start over, we took a trip on the sailboat, which was a month-long goodbye. As a kid, I found it extremely upsetting and confusing, and I could feel this heaviness that we were all not talking about.

FWR: What you’re describing, being a child and being aware of these things not being talked about but felt, this to me, speaks to how you thread the personal and political through your poetry. You’re aware of the bodily privileges you have, as an outwardly white woman, but also the bodily disadvantages you have, from being a woman. This creates a mixture of tension and privilege, for example in a poem like “Arson is a Family Name”, written in response to white women who voted for Trump, or the poems that deal with the relationship your husband has with the world, such as “I Suggest Omid Shave His Beard”.

KGT: Omid, my husband, is Persian. Both of his parents were born in Iran but he grew up in California. From this relationship, I’ve experienced stepping into how the political plays out in the everyday. My husband is a very gentle soul but he was also very clear when we got together that, because he is Middle Eastern, the world, especially the white world, thinks that he was going to treat me like shit. He was so conscious of the stereotype and aware that every choice he made was to defy that stereotype through kindness. When Trump first came to office, I remember that Omid’s father and mother told him to shave his beard because it is not safe in this country for him. I’ve thought about that a lot.

FWR: What you’ve said about his beard, that is a variation of the idea of the body as performance. By shaving his beard, it makes him more ‘accessible’ or sending the message that he’s not ‘like those other people’.

KGT: Totally. I’ve learned so much from him, in terms of how he won’t apologize or won’t perform. But as a woman, society has trained me to perform. I feel overly programmed and conditioned that there is something about me that needs to be fixed. I think that’s a gender thing, but I think it’s also a marketing and targeting thing.

FWR: This makes me think of the performance of sexuality and sensuality. I think you thread a fine needle between those two, as there are poems that are sexy and there are poems that are sensual, and yet they do not seem as if they’re meant to titillate. It made me reflect on male writers who will treat the woman’s body as something to be objectified, and thus demeaned. I was wondering if that was something you were conscious of as you were writing.

I think through that sensuality, I am opening a bridge to acceptance.

KGT: I don’t know that I always think about, or even do think about, about the line between sensuality and sexuality when writing. Whenever I have a dialogue about sexiness, there’s always the insecurity there. I can’t always separate those, though I’m getting better. From Omid, I’ve also learned about self love. It’s been a hard thing for me to feel like I’m beautiful. I think there is a sensuality in appreciation of the body, and tenderness and beauty. There’s an intimacy that comes from this, and I think that’s what’s coming across in the poems. I think through that sensuality, I am opening a bridge to acceptance. Intimacy, for me, is not pulling away. It’s agreeing to let someone look at you, and not feel the shame that you might feel. There is a trust in that, and there is a trust in someone teaching you to love the body.

I’m always working towards self love. There are many poets who have said that every poem is a love poem. While I think there are a lot of heavy themes in this book, I think it was a love poem to myself and to the women around me. I can think of the women who raised me, or the women I work with, who are amazing and strong, but they are not told that or that they’re beautiful. In fact, they’re often told the opposite. So I think this book is a love poem for them.

FWR: Does it feel like, with the book out in the world, that you’ve been pushed to the forefront of your own self love?

KGT: A year ago, I don’t think I was there. There’s a specific line in the poem “In an Attempt to Solve for X: Femininity as Word Problem”: “Tell the junior at UCLA/ you have the answer. Use words like better now / then walk her to her car. Do not tell her/ like you, she will always be hungry.” It sprang from a friend who I had told what I was writing about, and she asked what I had figured out. I felt like a fraud, saying that I didn’t know. I felt like I had to have all the answers. The book came in different stages, over years, as any book does. At the end, I had rewritten probably 30% within the last six months before it was finished. It changed and changed, as I thought it could be better.

I started in a place of shame and punishment, and then I asked myself what conversations could lift me out of that.

I believe that a poetry manuscript, like a piece of fiction, should have an arc and an ending. There’s growth and transformation in all art. I believed that not only was I taking myself on a journey, I wanted the reader to be on that journey too. So, the poems at the end of the book, I wrote with the intention of healing and with the intention of dialogue, and the intention of praise and honor. I started in a place of shame and punishment, and then I asked myself what conversations could lift me out of that. Now that it’s out, I do think that I love myself in a completely new way.

I was really intentional to have a dialogue with the self and with the body that represented women in their multifaceted complexities, that came from a place of deep introspection and love. It’s not that I have all the answers, but I have more answers than I used to. My definition of beauty has shifted, my definition of power has shifted. My fundamental beliefs have shifted in a really beautiful way.

Before the book came out, my mother and I drove to Las Vegas. She asked me to read through each poem, and after every poem, we stopped and talked about it. It was one of the most healing, beautiful things that I have ever experienced. I think part of this book was to come to terms with the fact that yes, there was a lot of sadness for me, but there was also a lot of sadness for my mom and my sister and the women around me. No one talked about it until years later. This book is an effort to do that, to hold one another.

FWR: It feels as if it’s also unfurling the layers of shame and body back, to say that once we’ve gone through all these depths, here we are as people and true to themselves. It reminds me of what you said earlier, about having this discomfort with your body after about the age of seven.

KGT: Exactly. I very much want to be a mother, however I come to be a mother, and I felt that I had this responsibility to deal with my shit before my children come along. It’s so important to me to celebrate my child for who they are, without my hang ups. I think shame is learned, and while some of that shame is necessary, there is so much additional shame for our natural body. It takes muscle to unlearn that shame.

FWR: This tradition of parents passing down shame, or their ideas of what’s natural, that brings to mind the poem “My Father Tells Me Pelicans Blind Themselves”. Though I know it comes much later in the text, to me it felt like the entrance into the whole of Boat Burned. It wraps in ideas of family who both love and wound each other (“[they] hatch/ hungry children. They peck/ at parents who strike/ back”), the body (“appetite: my deepest/ grave”) and the desire to turn both of those very human experiences into a lesson or, at least, a story that can give meaning to us (“they starve into myth”).

KGT: When I think about my family, I think there’s so much of us that exists in these corners of silence and that is silenced around the hunger we have for the things that we are not getting or giving each other. This leads us trying to fill that lack. I think of the line, “I have drunk all the body that this wine will allow”; you come to a point that the sadness or the silence is so deep that there’s no outrunning it. That poem ends with the lines “Father, rock me/ like a child./ Sing me the sea“; there’s a sweetness in that and a surrender. I don’t know if I will ever outrun this and at many points in my life, hunger, or the insatiability of it, has felt like a type of violence against the self or against others.

In “The Polite Bird of the Story”, I have the line, “Food is just another ghost story/ the starved like to tell.” I feel like that role of food being a ghost story, is the same function as love in the book. You’re so starved for love that you do these things, whether taking on shame or apologizing for yourself, because you’re so hungry. I’ve been on a diet since I was eight years old, so yes, I am hungry all the time. Either I feel like I’m hungry, or I feel like I’m fat because I’m eating what I want, but I am also hungry for so many other things.

FWR: This reminds me of the poem “No One Says Eating Disorder”, when you end with the lines, “The small gods/ we let control us. / We were so hungry/ for anything/ to love us back.” That desire to feel something, even if it’s not the feeling you wanted.

KGT: Yes, that feeling to feel wanted is such a human need, and it’s even more complicated for women. We are taught that we are put on this earth to be wanted, to be these things of beauty. All we want is to get some kind of love, and when you don’t get that love, it turns into a form of self harm. It becomes a never ending cycle.

FWR: Part of what I think you do so well in this book is that you talk about that cycle, and that inheritance of cycle.

KGT: I think speaking of that cycle is the first step to breaking a cycle. I work with youth poets, and I feel like I have a responsibility there to show both sides of the looking glass. As an adult, as a mentor, it’s important to do the work so that you can get to a place where you can help others.

I had to learn Algebra Two, but not how to love myself.

Out of all the poems from this book, the one that has gotten the biggest response is “No One Says Eating Disorder.” I’ve done poetry readings, and women will come up to me to say, ‘thank you. This is not something we talk about.’ I was so scared to write that poem, because I feel like it’s such a cliche to be a white girl talking about body issues. It feels like there’s a vanity there or that it’s not a real problem. But I think the lack of self love in this country is a real problem. I had to learn Algebra Two, but not how to love myself. And I have never used Algebra Two!

I think there’s so many wonderful things about being a woman, but I don’t think that that’s highlighted on a daily basis.

FWR: I wonder if I could ask you about “What the Neighbors Saw”. Reading this poem, I was struck by the structure of the poem and how it mirrors the fragmenting of thoughts and emotions after trauma, and how that fragmentation becomes the memories themselves. It ripples across the page, as words and images (the butter, the door) revisit the speaker and gain new resonance. The syntax shifts throughout the poem means that each line unsettles the next and previous. Could you talk about the development of this poem?

KGT: I was at the Kenyon Young Writers Program, and I was a fellow for them. I was instructing but also learning. We had read “Dead Doe” by Brigit Pegeen Kelly. I was rocked by the language and the imagery and scenes, and I was rocked by the interruptions and how real those interruptions felt as emotional symmetry.

I’m really connected to the idea of motherhood and wanting to be a mother. I think some of the greatest pain someone can experience is losing a child, or not being able to have a child. So I was thinking a lot about children, and the other fellows and I were given this writing prompt where we each wrote images on index cards and passed them around.

That poem, I sat down and wrote in about 15 minutes. It came out whole, except for maybe two lines that I cut and some things I tweaked. That poem is a journey for me, inside life and stories and a complicated house. It’s not biographical, except for feeling emotionally true. It’s still rooted in the autobiographical experiences of the book and the same threads of shame, silence and punishment.

FWR: To hear your process, it matches the experience of reading it. The poem is so emotionally wrought; the fragmentation reminds me of a record scratch, where it continues to be stuck on an image or idea.

KGT: I’m at the point in my life where I think about motherhood, and I am struck by how fragile it all is. When you’re thinking about the role of the daughter, you’re also thinking about the role of your own daughter, or at least I am. There’s a line where the husband says they can start again, and the speaker had to assert that she is still hurting, and that it will be her body that will feel motherhood from the beginning. I think it speaks to the evolutionary pressure on a mother, that we were supposed to care for the children and make sure that they don’t die. That is another expectation for women and the role they must perform. This poem speaks to what happens when a child dies, and how the world responds to that and how a mother internalizes that.

FWR: Although I have a good sense from your acknowledgements, were there poets or writers you turned to for guidance as you began to explore these topics in your writing?

KGT: My biggest poetic influence of all time is, by far, hands down, Patricia Smith. I was introduced to the poem “Siblings”, which explores the different personalities of hurricanes. Because I grew up on sailboats and my dad lives in Florida, I have a close, personal relationship with hurricanes. They’re kind of like a family member that comes around every August. I was really affected by the way she personifies these hurricanes. When I first came to poetry, Patricia Smith and Rachel McKibbens, both, blew the lid off of language. When I read them, it’s electric. I can feel the way they play with language, or manipulate parts of speech, or throw out syntax, through my body. Those two poets unlocked a gate for me when it came to language. It’s like I found a whole new part of being.

I never got a degree in poetry, but when I started publishing, I decided I was going to go to some workshops with poets. The first one I ever went to was Tin House’s Winter Workshop with Patricia Smith. It was amazing, and I learned so much from her. She is one of the most beautiful human beings I’ve ever met. I’ve been lucky to study with Jericho Brown, with Danez Smith, with Paige Lewis. I remember that there was a poem that Jericho Brown asked me, “what is this? There’s such a distance here. You’ve either got to let us in or not write about it.” And that helped shape how I approach my writing.

Another person whose work I gravitate towards is sam sax. He does a lot of really interesting stuff with language and in terms of performance, I find him to be really captivating. The last person I want to mention is Shira Erlichman. I’ve studied under her but she also helped me in terms of editing and working with me one-on-one. I love the way she looks at language, what she calls “peanut butter and fireworks”: the things that normally don’t go together but can create tension and complication in language in fascinating ways.

FWR: I completely see those elements in your writing. Patricia Smith, I think, is so good at detail. Her language is gorgeous but she never loses sense of the physical. She roots her writing in the world, even as you follow along with these grand ideas. I think each of those writers, Jericho Brown, sam sax, it comes back to the body and the body in this world.

KGT: I agree, and I think they all talk about the complications of the body. The body is a responsibility that’s heavy, that we carry in so many different ways. I heard Nikki Finney say that one of the keys to writing is “never arriving, always becoming.” As poets and writers, we always have to be working to improve ourselves and to improve our language, and continuing to read and learn. I think about that all time. I think I have a little more of that, because I didn’t go the traditional route for writing. And I think I have a hunger to always be learning from those around me. It’s important to keep transforming.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Dilruba Ahmed

Dilruba Ahmed is the writer of Bring Now the Angels (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020) and Dhaka Dust (Graywolf 2011), which won the Bakeless Prize. Ahmed is the recipient of a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Memorial Prize, and she holds degrees from the University of Pittsburgh and Warren Wilson College’s MFA Program for Writers.

FWR: In an interview with the New England Review, you stated that, “I’m interested in the ways that—particularly during difficult times—a seemingly small act can contribute to a greater purpose. And how those acts, even when they occur in relative isolation, can bind people together toward a common goal. While you made this comment while reflecting on the term “resistance” with respect to your poem, “Underground,” I think it speaks to the other poems in Bring Now the Angels, as well. Illness frames much of the text, as you reflect on “SickDad” and how cancer impacted your family with an eye towards the minute detail.

In the poem “Local Newspaper, Floating Photographer, Father’s Day Edition”, you describe images of vitality: “Describe your father. / Midnight scrambled eggs each New Year’s Eve. The insistence: ‘say yes to cake’ … Describe your father / Why do children keep growing, in their small and ignorant bliss?” Each of these small moments construct a man and a life, and by sharing these moments of specificity with your reader, you have brought us into this man’s life more effectively than broad strokes. In this movement from the broad (father; illness) to the keyhole (“pizza purchased for men searching dumpsters in Columbus”), did you find it easier to write about small moments? How did you find the lens with which to view these grander, binding moments?

Dilruba Ahmed: My new book, Bring Now the Angels: Poems, is an extended meditation on loss, both personal and public. In the personal realm, the poems mourn the many losses associated with chronic disease and terminal illness in the Western world. During a 3-year battle with multiple myeloma, my father lost his health, his mobility, and his typical daily activities. Some changes were sudden and dramatic; other losses accrued slowly.

The ripples kept growing. We experienced a loss of confidence in Western medicine, which both saved my father and destroyed him, and for me, in faith. The disappearance of our bearings and touchstones transformed the world into a place suddenly strange and unfamiliar.

The situation was painfully personal, but everything happened within a larger context. We witnessed firsthand the cost of being ill in America: the associated expenses, maltreatment, discriminatory practices, and reckless over-use of painkillers. Not to mention access issues to dialysis centers and the related questions about quality of treatment and quality of life. In each health care facility, for every deeply caring and attentive health care professional, there were physicians who were out of touch with their patients and the mission to heal. My family members and I experienced the corruption and carelessness of our country’s healthcare system even as a few shining stars gave my father the best possible medical attention he could have requested.

While small moments often sparked poems like this one, in my revisions I’ve tried to consider their larger contexts so I’m not just “zooming in” but also “panning out.” I’m making an effort to examine the layers surrounding personal moments by asking, “What are the social, cultural, and historical contexts relevant to this poem? Who has been represented here, and who has been erased?” Claudia Rankine has called for white writers to examine how the racist history of our country has shaped mainstream thinking about both whites and people of color—and our representations of both. From the intersections of my identity, there’s still work to do as well.

These questions have led to deeper revisions, as with the title poem of my new book, “Bring Now the Angels,” which began as a measured acceptance of a terminal diagnosis and the adjustments accompanying physical and cognitive losses. In subsequent revisions, I situated personal loss in more universal ways, focusing less on the diagnosis and more on the indictment of a society that permits the vulnerable to suffer under dismal conditions, with poor medical treatment and exorbitant costs. I revised from a first-person narrator to an oracular, choral voice that bears witness to maltreatment, misuse of addictive painkillers, and debt.

FWR: In the poem ” With Affirmative Action and All’ , you write, “in any given American town, / there is a room inside a room inside a room/ where thought shapes word shapes action”. Several of your poems, such as this one, or “Self-Guided Tour”, wrestle with what it means to be in America, and what America means in a globalized world. Did you look to other poets for guidance in writing about the political in our current state?

RA: Yes! I have many inspirations informing my poems – sometimes overtly, sometimes playing it the background like a poetic playlist.

In some poems in Bring Now the Angels, I was experimenting with W.H. Auden’s notion of “indirect communication” with the reader. Auden believed art couldn’t move people to faith, for example, but that it held power to show them their despair. My explorations led to poems such as “Choke,” which recasts “Jack and the Beanstalk” in two voices: an unidentified interviewer and an Indian farmer. In the poem, I envision the effects of large-scale corruption on the individual, with hopes of eliciting awareness. In “The Process,” I try to channel the distanced tones of Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” to critique our shared complacency, hoping readers will realize our collective agency. In “The Children,” a poem meant to locate our heartbreak and humanity as immigration policies shift dramatically, I attempt to capture intimacies between parents and children in stark contrast to brutal family separations at our border.

One of the more overt influences on my politicized work includes Roque Dalton, a Salvadorean poet whose poem “OAS” holds both dry wit and bitterness. His work inspired my poem, “Self-Guided Tour.” More generally, Adrienne Rich’s writings frame my engagement with politicized material: “No true political poetry can be written with propaganda as an aim, to persuade others “out there” of some atrocity or injustice… it can come only from the poet’s need to identify her relationship to atrocities and injustice, the sources of her pain, fear, and anger, the meaning of her resistance.”1 In my writing, my hope is to embody resistance on multiple levels. For example, “Underground,” attempts to situate the resurgence of American civic engagement, including my own. Striving for a global perspective, I tried to broaden my focus beyond conventional actions such as public marches and activist phone calls. I wondered how might I witness courage and agency that goes unseen—actions not necessarily recognized as resistance.

My musings resulted in a poem about private and public resistance by Afghani women under Taliban rule. I strove to represent the women’s resistance as not only fighting back, but also finding ways to thrive under threatening circumstances. By engaging with this material, I hoped to lend perspective to the present American challenge of political organizing among work and family obligations—actions that occur, for many of us, within an existence of relative privilege and freedom.

There are many, many poets who make up my playlist when it comes to politicized poetry, including Claudia Rankine, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Rick Barot, Ilya Kaminsky, Matthew Olzmann, and Elizabeth Bishop….

FWR: In this vein, the poem “Incident” has haunted me long after I first read it, with its juxtaposition of maternal love and parental violence. It also seems to read as an ars poetica, with the lines : “If I love my sons— / their sleep-ruffled curls… with even more ferocity/ and mindfulness, can I erase / the girl’s pain?” It also reflects back the love and pain that is so often built into relationships within families. Could you speak to this poem?

RA: One of the questions fueling Bring Now the Angels is related to witnessing the suffering of others, and the resulting sense of powerlessness to enact change. I think that, for those of us who may feel overly porous to the world’s violence and the distress of others, everyday living can quickly become very overwhelming.

With my father’s sudden decline and subsequent diagnosis of multiple myeloma and end stage kidney failure, in many cases there was very little I could do to alleviate his suffering. But through it all, I’d like to believe that the loving presence of family members provided a healing force. In my poem,“Incident,” I was grappling with both a sense of powerlessness over other’s actions, and the possibility that greater harm could result from any apparent response from me. Because this poem was based on an actual incident, the poem also speaks to the ethical dilemma of failing to act—by not attempting to intervene as a situation cascaded into violence, did I in effect participate in that violence? I, too, remained haunted by this incident and have been unable to reconcile it for myself, despite the risk of unintended consequences for the person I felt compelled to help.

And you are right: the poem could be read as ars poetica that both laments the seemingly ineffectual nature of poetry to create change in the world even while trying to recenter the speaker’s energies on mindfulness and deep love. In the end, the poem implicitly yields to the fact the speaker only has power to effect change in the realm that is most directly hers, acting from a deep love that could, perhaps, hold the potential to ripple out beyond the immediate moment. But ultimately, the poem consists of a series of questions for which there are no answers.

FWR: Much of this collection wrestles with grief. How did you approach this experience in your writing? Did the poems emerge organically, or did you sit down to write about loss? Were there poets you looked to?

RA: In an interview with Terry Gross, poet Marie Howe says poetry is “a cup of language to hold what can’t be said,” explaining that “[e]very poem holds the unspeakable inside…The unsayable…that you can’t really say because it’s too complicated…too complex… Every poem has that silence deep in the center…”2 Writing about grief was very much a process of finding ways to access those deep silences.

To convey my emotional truths about chronic illness and loss, I tried different approaches—lyric, narrative, and prose poems, with tones ranging from deeply intimate to the distanced language of form letters, medical records, and Google’s autocompleted phrases. Restlessness regarding form and content’s relationship led me to write ghazals, as well as poems with less conventional structures–including one governed by a childhood toy, the Viewmaster.

Many of the poems emerged in a flood of writing about one year after my father’s death. As daughter and as a parent, I’d struggled with my understanding of mortality without finding ways to authentically engage with it in my writing. When an old story about my uncle’s childhood snakebite assumed mythic proportions, I found that the use of parable finally helped me to unlock some related emotional truths. The result was “Snake Oil, Snake Bite,” one of the first pieces I wrote about my father’s battle with cancer. I knew then that I’d made my way to the poems that would form the new book.

Literary heroes in this endeavor include Marie Howe, Agha Shahid Ali, Carl Phillips, Elizabeth Bishop, W. H. Auden, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Donald Justice…

FWR: I was struck by the shape of your poems. I am hoping you might speak to your process in a poem like “Vanishing Point” or perhaps your use of the ghazal form?

RA: “Vanishing Point” took on many shapes during my revision. In the end, I aimed for a shape to convey the slipperiness of memory and the general sense of unease. I will forever be a student of the ghazal form; this book represents my most recent efforts.

FWR: I always love to ask: what the poems or who are the poets you love to teach or share?

RA: There are many – Donald Justice, Elizabeth Bishop, Agha Shahid Ali, Ilya Kaminsky, Natasha Tretheway, Mathew Olzmann, Gabrielle Calvocoressi, Rick Barot, Ann Carson, Craig Santos Perez, Jenny Johnson, Adam Zagajewski…

1. “Power and Danger: Works of a Common Woman.” Introduction to The Work of a Common Woman: The Collected Poetry of Judy Grahn. Oakland, California: Diana Press, 1978; New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1978. Reprinted in On Lies, Secrets and Silence, pp. 247-58

2. Poet Marie Howe On ‘What The Living Do’ After Loss https://news.wbfo.org/post/poet-marie-howe-what-living-do-after-loss Originally published on October 21, 2011 10:23 am

- Published in home, Interview, Monthly, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Oliver de la Paz

Oliver de la Paz is the author of five collections of poetry, most recently The Boy in the Labyrinth (U. of Akron Press, 2019). The Boy in the Labyrinth works in poems that utilize autism screening questionnaires, prose passages, and allegory via the Greek myth of the labyrinth and the minotaur to explore de la Paz’s experience in raising two neurodivergent children who fall under the Autism Spectrum. de la Paz is the co-editor of A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry (U. of Akron Press, 2012). He co-chairs the advisory board of Kundiman, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to the promotion of Asian American Poetry, and teaches at the College of the Holy Cross and in the Low-Residency MFA Program at Pacific Lutheran University.

FWR: The Boy in the Labyrinth functions as a type of katabasis, a descent into the underworld. This gives the manuscript structure, and, to me, a feeling of reading a novel. You write in “Twenty-Eight Tiny Failures and One Labyrinth” : “I realized that I had been writing about my sons for several years in the form of this allegory”. When structuring the manuscript, did you treat it as writing a complete whole (like a novel)? Or did you find that emerging organically, after you had begun constructing the poems?

de la Paz: When I started writing the “Labyrinth” poems I had no intention other than to explore atmosphere and tone. The process of writing those specific sequences only started shifting right around my third year of generating more of them—I was probably thirty to forty poems into what wound up being almost one-hundred poems. As I became more conscious of my process, I became more intentional in implementing narrative elements. Threads of sequences have similar settings and characters, for example the boy in the sky became a character for a handful of poems. Additionally the opera house became a locus in a few of the poems. All of these disparate entry points into the world of The Boy in the Labyrinth created organizational issues. It wasn’t written as a linear narrative and yet I needed to convey to the reader a sense of forward movement. My restructuring of the collection began four years ago when I began to write the “Autism Questionnaire” poems. I saw the “Autism Questionnaire” poems as mile markers in the progression of the work. So I began structuring around them as though the book as a whole were a three-act play. I then layered the “Labyrinth” poems around them to suggest momentum/movement. And I also added the Greek Chorus elements to the work as a nod to the structure of the Greek Tragedy.

FWR: On this note, The Boy in the Labyrinth veers into different inventive forms and poetic structures, such as the “complete the sentences” poems or the use of the Autism Screening Questionnaire. Were there other forms you attempted to unlock these poems? How did you decide to utilize these structures?

de la Paz: The forms came to me organically. I was thinking about all things “diagnostic”, like SAT or GRE questions [and] how they’re expected to create an understanding of the test-taker based on an algorithm. The “Autism Screening Questionnaire” poems were something that I approached with a great deal of intention after having completed a series of intake forms for my middle child. And by intention, I mean critique. I wanted to quarrel with the form. There’s the expectation of the binary “yes/no” response to the form, but they’re a flawed tool, so I wanted to respond to the questionnaires from an emotional position rather than a diagnostic one. Once I started writing poems in that diagnostic structure, I felt the need to explore other structures. So you see a number of standardized test-like forms throughout the book with the “Story Problem” poems that close out all three sections. I imagined the “Story Problem” prose poems to serve multiple duties—to invoke diagnostic forms but to also highlight the challenge of my perspective as a neurotypical parent writing about my neurodiverse children.

FWR: Staying on the questionnaire poems, it seems to me that they suggest the imagery that you utilize in the episode poems, which take place in the labyrinth sections (self harm, unusual tastes, kinetic movement and soothing). I experienced that tension as a means of making sense of a neuro-divergent experience as a neuro-typical reader. We, as a reader, are experiencing the distortions of the boy in the labyrinth, whose “voice tries to pierce through the gloom… the sound of him spills its waves into a disfigured future.” Can you speak on this?

de la Paz: Yes, the “Labyrinth” episodes do highlight the moments in the questionnaire that are viewed as “deficits” to the neurotypical population. I wrote most of them as I was still learning and growing as a parent. It’s interesting, but much of the work in the episodes trace my development as a parent, so it’s a chronicle of my misunderstandings and in many ways, failure and flaw. The writing is asynchronous with who I am and who my children are now, so I must first acknowledge that. And what I’m very clear about now is that much of the work as I was writing explores this “disfigured future” but that future, as I had conceived of it, was the future of my imagination and not my child’s. As I was writing the “Labyrinth” poems, I was really writing about and for myself. It was a way of measuring time and comprehension and I look back on it now as an artifact. Certainly, I’m proud of the work that I had done but I am also aware of how it may be perceived by the neurodivergent populace. And so that voice that is trying to pierce the gloom is my voice trying to start a dialogue, both with my children and with other parents who may be as lost or fearful as I had been.

FWR: Reflections and refractions feature prominently in the work: geodes, light splashing off water, the appearance of the minotaur and his masks, the shadow boy. Are we, the presumed neuro-typical reader, the minotaur? Or is this an example of “the labyrinth turn[ing] in circles and [multiplying] its falsity”? An attempt, to quote another poem, “because a reference needs a frame: we are mother and father/ and child with a world of time to be understood”?

de la Paz: You know, the minotaur was always a character that troubled me. I always imagined myself to be the minotaur—the devourer of Athenian young. I imagined the monstrosity to be the task of taking on the story. The beast is as lost as the boy in my tale. I was always fearful that the monster would be misconstrued, so I took steps to move the monster and boy towards a reconciliation. I think, as well, that the “Story Problem” poems that mark the three sections are my way of saying that writing from my neurotypical perspective about neurodiversity is fraught.

FWR: We normally close by asking writers to share other writers or pieces that they love to teach or share. I wonder if, in addition, you might point to writers who influenced this work.

de la Paz: Sure, there were multiple. I started writing the “Labyrinth” poems after hearing the poet David Welch read from a new selection of work back in 2008. I believe those poems became the book Everyone Who is Dead.

Alison Benis White’s Self-Portrait with Crayon was a tremendous influence, namely the obsessive quality and interlocking nature of the prose poems.

Meteoric Flowers by Elizabeth Willis was something that I would refer to if I wanted to bounce around some syntactic shapes. I really enjoy that book and the shapes of its sentences.

I read a lot of Jennifer Chang’s book The History of Anonymity, again for the shapes of her sentences.

I also want to put in a plug for an extraordinary book of rhetoric by Melanie Yergeau. It’s a rhetorical analysis book written by an autistic author who is using queer theory as an analytical lens for disability writing. I also want to plug the work by Chris Martin and Mary Austin Speaker over at Unrestricted Interest. They make extraordinary chapbooks.

- Published in home, Interview, Uncategorized

INTERVIEW WITH Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach

Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach is the author of The Many Names for Mother, selected by Ellen Bass as the winner of the 2018 Stan and Tom Wick Poetry prize and published by Kent State University Press. Her second collection, Don’t Touch the Bones won the 2019 Idaho Poetry Prize and is forthcoming from Lost Horse Press in March 2020. Look out for her newest collection, 40 WEEKS, forthcoming from YesYes Books in the fall of 2021.

Four Way Review: Throughout The Many Names for Mother, there is a recognition and fracturing of identities (mother, child, immigrant, woman)– where does poet fit? On this note, how do you guard your time for writing?

Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach: I’m going to start with the second half of your question, as I sit at my favorite writing café, having just nursed Remy for the umpteenth time, now rocking the stroller with one foot as I type the answer to this question and watch her drift in and out of sleep mid-cry. So, guard? I’m certainly not there yet with the 2-month-old (as I’m now down to typing this with one hand, holding her with the other). Truer to my experience is that I make my writing a part of my mothering and mothering a part of my writing.

Since becoming a mother, I think I’ve become a keener observer of the world around me, learning from the way my son takes it in. Everything he sees is new and marvelous. Everything is a kind of epiphany. Everything I thought I knew all too well is transformed to a revelation. And this is what poetry strives for also, to make our shared human experience feel at once familiar and novel.

This is also the case for language. Watching my son learn how to make sound and then meaning has shown me that children are born poets. Metaphor comes as naturally to them as speech. It’s the way they make sense of the world, through magical comparison. I first noticed this when my son became fascinated with the moon. He would find it in the sky at first, and then, he began seeing it everywhere. Each circle or light became “Yuuuuooona,” his way of saying the Russian word “Luna,” meaning moon. And this is metaphor. Seeing the likeness in two unlike things, comparing the celestial body of glowing rock to the dark ring of my belly button to the puddle outside to the wet outline his tiny mouth leaves on my shirt. This is an image chain. This is my child making poetry, and me stealing it from him for many poems in the book, but especially the poem, “In Everything, He Finds the Moon.”

In Everything, He Finds the Moon

Yuuuuooona, he calls, pointing up and drawing

out the ooo, the Russian “L,” still

too hard to form “Luna.”

We understand, make meaning

out of what its left us: Yuuuuooona,

on the shoulder of my shirt

where his sleeping mouth’s wet outline

left imperfect waning, Yuuuuooona,

in the fabric covering my belly, where

his finger found a hole through which

skin shone like moonlight, Yuuuuooona,

on the wings of every moth or butterfly,

Yuuuuooona, more Yuuuuooona, our cats’ eyes

twinkling in darkness, spinning spheres

he is still too slow to catch, My Yuuuuooona,

in the daylight’s glare, he names the sun

as his, asks it to come closer, and opens wide

to hug, to swallow, to hold

its unfathomable glow, and in the water too,

in any water, Yuuuuooona, Yuuuuooona,

bath, puddle, lake, sea, ocean, rain,

our faces and the light, a river, and

in the window, any window, especially

a stranger’s, Yuuuuooona, this December,

morning, through smoking sky

and a cobweb of trees, he finds it there,

even as it fades, and in my pocket,

I find it too, Yuuuuooona, an envelope

of his first-trimmed crescent hairs,

so many fallen moons.

Originally appeared in 32 Poems

I thought that having children would turn my gaze away from the ancestral past I’d been obsessed with throughout my poetry career, and towards a future unburdened by it. On the contrary, having my son has made me think all the more about the lineage he comes from, the traumas of the Holocaust, WWII, and immigration into which his own story is unwillingly written. In fact, I’d been trying to publish a poetry collection about immigration and ancestry for four years, but it wasn’t until being pregnant with my son and writing, “Against Naming,” the opening poem of this collection, that this book and the real story I had been trying to tell, finally took shape.

Becoming a mother has not only changed my relationship to poetry, but more critically, to the past, which is now inexorably tied to the fleeting present. Motherhood feels like a uniquely lyric experience, relishing in an instant as it swells to include temporalities that came before and the potential of all the ones to follow. It’s also an intergenerational experience, connecting me to all the mothers I come from, while helping me find a home in my own body as it exists in the present moment.