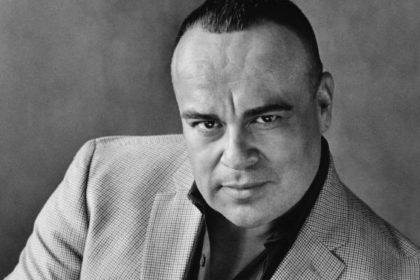

INTERVIEW WITH Rigoberto Gonzalez

Rigoberto González has written books spanning poetry, young adult literature, children’s literature and memoir. His most recent book of poetry, The Book of Ruin, was published by Four Way Books in 2018. He has been awarded fellowships by a variety of organizations, including the Guggenheim Foundation and the NEA, and recognized with the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets, the Lambda Literary Award for Poetry, and the Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America, among others. He is a professor of English and the director of the MFA program at Rutgers-Newark.

Four Way Review: As I read The Book of Ruin, I kept thinking of the word “revelation.” It has both apocalyptic connotations, as in the Book of Revelation, and also positive, as enlightenment can give us guidance. This play between pain and knowledge threads through your poems. Does knowledge always necessitate pain?

Rigoberto González: I believe that pain can be physical or emotional, as in the revelations or epiphanies that come to us after we make mistakes or make the wrong choices. Also I’m gesturing to that common phrase, “The truth hurts.” To achieve clarity something has to be surrendered or compromised, and most of the time it’s our caprices, comforts, or stubborn ways. This may sound like a terrible process, but in fact it’s a way out of a terrible place that we don’t recognize or refuse to recognize as toxic. We become accustomed to unhealthy situations. We make a habit of negative feelings and conditions. We grieve what we lose, no matter the benefits of gaining knowledge. It’s a beautiful flaw that makes us human.

FWR: In one of your recent Los Angeles Times columns, you write: “It’s the immigrant condition to always explain one’s distance from home as a way to make peace with the separation.” To me, this gets at the idea of liminal space and how immigrants (and poets!) must, at times, exist there, in places of transition.

These transitions exist throughout The Book of Ruin; in some poems, this enables you to speak for the unheard (nature, for example, warning humanity that change is coming) or the silenced (a poem from the point of view of the father of one of the Iguala students forcibly disappeared in 2014). In “43”, a poem that threads both one’s relationship to the land with the vanishing of a murdered child, you write: “You’ve become/ the man on the crest of the land of the dead– / earth force-fed the evidence of man’s insidious/ acts that rots its viscera away.” This poem falls within a suite of poems (A Brief History of Fathers Searching for Their Sons) that see both fathers and nature in positions of mourning and perpetration. But in “43”, there is a transference from the destruction we wreak on the earth to the pain we cause one another. Can you speak to the development of those poems? Did you initially begin that suite planning to write on the Iguala students?

RG: For me, the book came together in 2014. That was the year of the Iguala travesty, that was also the year of the Ferguson protests sparked by the murder of Michael Brown, it was also the centennial commemoration of the Ludlow Massacre, in which mostly women and children perished in fires set by the National Guard as a tactic to quell a labor strike at the copper mining town. All three events appeared to mirror or reflect the rage and frustration we were experiencing with intense natural catastrophes brought on by climate change. The natural world and the human world were colliding constantly and we sat at the crossroads doing so little about it that we might as well do nothing. I didn’t write about Ferguson because I felt it was not appropriate for me to do so when so many African American poets were writing heartbreaking poems about that and the current assaults on black bodies. But I did write about Ludlow and Iguala because Mexican people were involved. I chose the father-son relationship after I saw the father of one of our students at the Rutgers-Newark MFA Program attend a tribute to his son, who had been killed in a car accident. I saw him sitting at the train station with the saddest expression I had ever encountered. That took me to other instances in which fathers lose their sons—migration, war, political conflict, natural disasters. The larger statement here is that we are ushering in our premature deaths because we are destroying the planet and ruining our community’s health with our desperation, belligerence and aggression.

FWR: This poem brings me to the suite of poems “The Incredible Story of Las Poquianchis of Guanajuato”. These poems revolve around the Gonzalez sisters, who ran a prostitution ring resulting in 91 murders through the 1950s and 1960s. You write, in “Las Ánimas I”, “That you remember us/ says more about your deeds than ours.” While this might speak to humanity’s tendency to focus on the most violent or cruel moments of history, you go on to write in “The Fourth Sister’s Daughter”, “she too is part of the story, no matter how/ much it pains me to admit it to you”. Thus, the fourth sister [Carmen Gonzalez] must be remembered. What is the poet’s responsibility to the past? How can poetry instruct without giving undue power to those responsible for terrible acts?

RG: I’ve always believed that the poet has a responsibility to communicate the complexity of a life or issue or event, no matter who or what it is. I think people bristle at some of our subject matter because they’d rather it go away, be silenced, disappear from public knowledge as an act of self-preservation. (When I teach Sexton or Plath, for example, a few students usually express their distaste for the work.) And I understand that. But as the poet, I also know that we poets spend much of our energy unearthing, examining, and exploring even those things we find in the dark. Some call it bravery or courage, others call it foolishness, but I’ve yet to encounter a good poem that doesn’t want to show me something as opposed to want to hide something. Over the years I’ve accepted that criticism for my own work, even from close friends who tell me I only gravitate toward the sad stories and human tragedy. My response is that I write about what I feel is urgent and needs to remembered and said again. Silence is the precipice to forgetting.

FWR: Staying with those poems and the idea of silence, the cast of speakers here remind me of a Greek chorus, as they reflect on the lives of those lost and those responsible for their deaths. The suite ends with “Las Ánimas II”, in which the murdered women speak: “Being found was worse/ than getting lost. / We no more belong/ to this world dead than we did/ alive”. Myths thread through The Book of Ruin, and here, the mythologizing of the dead seems to reflect more on society’s tendency to rue rather than prevent. What brought you to the stories here?

RG: I had exactly the Greek chorus in mind when I wrote this poem. When I saw photographs of these sisters, all of them in black, I was reminded of Shakespeare’s witches or the mythological Three Fates. I came to Las Poquianchis right after the series of mass graves was being discovered throughout Mexico because I kept hearing that nothing like this had ever happened before. A familiar expression I’ve heard in the U.S. about the level of racism and white nationalism. It floors me because this only betrays a person’s lack of historical knowledge. I go back to another adage, “Those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it.” Well, here we are. That’s also what took me to the Mexican Revolution poem, where another travesty was committed against the Chinese community of northern Mexico. But I wanted to do something more with both poems. Therefore I decided to bring forth the lives of Las Poquianchis and complicate their motivations, because it was also not right to reduce them to evil—that makes them aberrations and a one-time story, when in fact Mexico’s poverty and lack of opportunity pushes many people into lives of crime. This doesn’t excuse or forgive criminal acts—that’s not the point of the poems. My purpose is to revisit these events in order to fuel a conversation about what shapes a criminal and what can be done to stop the cycle.

FWR: You’ve spoken about how your parents’ involvement with unions has influenced your work as a poet, in that your writing is part of a larger conversation to invoke change. In “Ghosts of Ludlow, 1914-2014”, you write “a century of silence in violence”. The story of the Ludlow Massacre, which I think has been forgotten or silenced for many Americans, is in conversation with contemporary events. Can you speak about this poem and how it fits within the larger conversation concerning class, race and power?

RG: I came to this poem through Woody Guthrie, my favorite protest singer. His song “Deportees (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” is what inspired my previous book, Unpeopled Eden. So when I came across his song “Ludlow Massacre”, I immediately connected to it because of my family’s lengthy relationship with unions. Since this took place in Colorado, I actually traveled there. Ludlow is now a ghost town with a run-down memorial. I even stepped into one of the pits that had been dug to shield the miner families from the cold—they had been evicted from their shacks because of the strike. It was in such a pit that people died. It was the Ludlow Massacre that turned the tide in favor of unions. And 100 years later, there’s now a political party that’s aiming to dissolve them. Again I ask: Have we not learned anything? Oh, we learned. And then we forgot what we learned. So now we have to have another devastation reminder. That just makes me angry and sad. When I first started considering I was going to write a book with environmental concerns, it was when the monarch butterflies were diminishing in record numbers due to deforestation and climate change. I grew up in Michoacán, land of the monarchs. Killing them was killing my homeland, my memories, and one of my greatest joys. I turned my anger into language, hence “Apocalipsixtlán,” the epic poem at the end of the book.

FWR: You begin the second part of the book with an epigraph from “Ozymandias” by Shelley. What follows are poems set in a post-apocalyptic landscape after environmental calamity (“promised land turned purgatory”). The speakers, the Bigger Ones, revile the Muddies and chase the Smaller Ones, who have journeyed North. This too is an immigrant narrative, albeit one seemingly more in line with Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower than what we may think of as migration today. Did you look to other writers for guidance as you constructed these poems that seem both speculative and prescient?

RG: Again, you found my exact reference. Octavia Butler is one of my literary gods. When I came across Wild Seed and Kindred in college, I knew I was reading incredible narratives set in the past but really speaking about the present. And when I read those narratives set in the future, like Parable of the Sower and Fledgling, she was also speaking about the present. But I also reread Eliot’s The Waste Land, Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Fifth Extinction, and Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. I read these books in order to keep my language grounded and fueled by critical thought and not distracted by my own emotions. I also wanted to try the long poem, so I read as many as I could in order to learn how to sustain its strength and energy. A few standouts were Carolyn Forché’s The Angel of History and, of course, Allen Ginsburg’s Howl.

FWR: Switching gears, what are the poems or poets you love to teach or share?

RG: That’s easy: Aracelis Girmay, Ada Limón, Harryette Mullen, Gary Soto, Dianne Seuss, Tyehimba Jess, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Mary Ruefle, and Li-Young Lee, to name a few.