WANING GIBBOUS by Matthew Groner

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

My dear friend started crying into her champagne, which surprised me, because we had been celebrating all night. I’d been sober for seven years, long enough to know that people sometimes cry for no reason when they’re drinking.

When I asked her why, she said it wasn’t my fault. I had made her cry before.

I watched the bubbles break the surface of her champagne. “It’s not even flat,” I said. “There’s no reason to cry.”

She dried her face, and we went outside to smoke a cigarette. The crescent of the new moon hung milky white in the clear Vermont sky. We’d each driven up from the city to visit mutual friends, both fleeing for our own reasons, which neither of us talked about. She said she was going to quit smoking as soon as the moon was a waning gibbous, which, according to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, is the best time to do it.

“You have to live your life by something,” she said.

I said, “The moon is 200,000 miles away.”

“You’re a city boy. You’ve never even seen the moon, not really.”

I had spent every summer of my childhood at a camp in rural Vermont watching the red-tailed hawks swoop into the trees and listening to the pond frogs. My parents had sent me there to “thrive in a natural environment,” but the only thing I learned was how to sneak out of the bunkhouse and find booze in town. None of it seemed worth explaining to her again. Once, I thought she loved me.

I pointed to the weathervane on top of the building and said, “You don’t need a weathervane to know which way the wind blows.”

“You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows,” she said.

“You have to live your life.”

“On the farm,” she said, “if you didn’t wean the calves during a waning gibbous, they would moo all night for their mothers, and it’s very sad when a calf moos all night for its mother.”

We both looked for something in the moon, but most of it hid in darkness. She nodded, took a sip of her champagne.

She went on, “If you wean them during a waning gibbous, they won’t make a sound. It’s as if their mothers never existed.”

Her glass was almost empty.

“Now that’s something to cry about,” I said.

- Published in Issue 17

TWO POEMS by Junious Ward

INHERITANCE

I was never the clean plate, I was the swirl

of flour-white biscuit in dark corn syrup.

At church I was a wide-mouthed Baptist hymn

whenever my father made eye contact.

Eight teabags bathing in a glass jar on the back steps,

sun high and fevered, I was a hot summer.

Who cares what the package says,

I was two cups of sugar instead of one.

I was Man-Man or Baby or Dee

or cousin Peanut from down the street.

A name in the South is a yardstick, becoming

the measure of both giver and receiver.

My friend Ten Pointer got his name by scoring

ten points in a basketball game, simple.

Don’t ask me about Uncle Alpo or Crack or the senior

in college who only let us call him Mynigga.

Dad reminds me during an argument the only

thing he can give me is his name as reflection

and his religion as legacy and what is he

if I walk away from either. I wasn’t the clean plate.

I was the swirl who only called myself black, not

white. Black. Which

felt like the only way to keep part of him

with me, to acknowledge what I’d been given.

HOMECOMING, RICH SQUARE, NC

I.

Northern black folk

drive through my hometown &

stop along the road

to pick cotton – a drifted piece,

something the machine skipped

over. Feel the need to connect,

honor ancestors by picking straight

from the claw of the plant’s mouth,

seed and all,

how thorny it feels, how it calls

out blood like the Big Dipper sang

a whole bloodline toward a lesser wound.

How can anyone do this

all day? I worked that field

as a kid. Only once. Burlap skin

as thirsty hands during an annual

event/reminder for families

in need of extra income.

Come, the Cotton Gin called.

Mighty fine job, sang Jackson St

from its own crescent mouth.

How callused these hands

and strong this back, I dreamed;

tan this skin, eager this frame.

A man. A man. A bag

of white gold taller than my dusty afro

earned $8.58, a check that arrived

two weeks later. Hell no, I never went back.

II.

My mother-in-law had never seen

a cotton field up close, this visit

she threw open the door

before I even got to a good stop,

went elbow deep and

picked one tuft clean and good, nervous

the landowner might see her working

his soil and pick up a shotgun,

noticed the blood on her fingers,

rubbed them pink,

and was quiet

the rest of the way home.

- Published in Issue 17

A POEM TO MY DAUGHTER AT THE AMUSEMENT PARK SHOOTING RANGE by Crystal Ignatowski

Nearly five. You

only know good

people. You still

dream of castles,

of knights on horses,

of growing long

hair. Three states

away is another

shooting. Pop pop. Bang

Bang. You just touched

your first fake gun

last week.

The amusement

park buzzed

like electricity

ready to go out.

You pointed the barrel

at yourself.

We all hesitated

then laughed.

Secretly,

we each felt seen.

- Published in Issue 17

DEVIL UNDERSTANDS DELIGHT’S ABANDON by Charlie Clark

I like how people still use the phrase dead of night.

It makes the night seem more exciting

and them more resigned to becoming ghosts as they move through it,

though no less oblivious to the fox skirting those trees waving

like two anemic legs shorn to the bone and waiting for the wind to break

them, though for the battery of their lives they have eked out

enough of something good here that walking with my child as she sings sugar

to her heart her heart doesn’t sink to see them.

Of all the sensitive documents I have eaten,

this one remains the freshest. Like that place on my leg

where the wound was. I still touch it roughly just to show the pain

is gone. It feels like dancing atop a frozen river with someone

on shore watching, waving above their head a branch as pointed as an antler,

as though that were the only thing you needed to keep you safe.

- Published in Issue 17

THE SORRY-ASS TRUTH by Tracy Winn

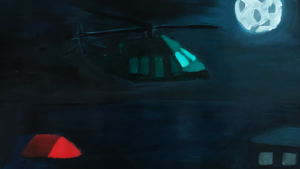

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

The Blackhawk hunkers in the pasture by the river like a video game beast, spiky and dark. Mikey slogs toward the helicopter, soaked with tiredness, lugging the baby, her ticket out. She’s ready to lie down in the sopping field, sink her banged-up body deep into the mess left by the flood and skip whatever comes next. But she has thirty-seven thousand dollars waiting for her in New York City.

A bug-eyed town official and a National Guard trooper with tattoos up to his ears scan a clipboard next to the chopper, which hasn’t started up yet.

Mikey holds the baby the way she’s seen other new mothers do it, rapt, like she’s in love. She can’t feel bad for being hell-bent. When the streams overflowed they washed out the roads, the power and phone lines drowned, the cell tower collapsed. The storm made an island of the town—cut the place off from even the nearest mountains. This ride is the only way out.

Mikey says, “We should be on your list.” Who knows if there’s a list. “Mikey Arbiteau?” She makes sure they get a good look at the black-and-blued side of her face. “This baby came during the storm.”

The town official judges her from behind his glasses. His name is Larry something, and he grew up with her father, but mentioning her father will not help.

“We’re supposed to be checked at the hospital.”

The two men look at each other. The National Guard with the multi-colored flames licking his neck says to Larry, “There won’t be another flight until tomorrow.”

Mikey leans for support on pallets of water bottles they just off-loaded.

The men are quiet.

Mr. Tatts-up-to-his-ears says, “The guy’s calmer now.”

Larry takes his glasses off and rubs his eyes and says, “She’s got a baby. We don’t have a choice, do we?”

The flying machine is a man’s space, black and hard, with too much metal—emergency handles, first-aid kits, and a fire extinguisher. The smells of diesel and mud. Mikey guessed there would be others on the flight, diabetics needing insulin, or old dialysis patients. But no way is she ready for Harrison Lenk. The guy she’s always dreamt would rescue her from her life sits by a National Guard trooper on one of the bench seats in the belly of the helicopter, pointing his gaze at her like the state of emergency is her fault.

She says, “Hey,” as if the hostile set of his face is nothing new, and nods at the young trooper next to him.

Harrison rests his head back on the window behind him, but his knees jitter. She hasn’t seen him since the night before he shipped out for Afghanistan, more than a year ago. In the weeks he’s been back, he hasn’t called her.

His cheekbones are wide and clean as a big cat’s. His eyes, usually the color of a classy dark rum, look flat. His shirt hangs unbuttoned. Dog tags nestle in the hollow just above his abs. He doesn’t smile. He has always smiled at her, even when it was only to be polite.

She wears the same T-shirt and borrowed sweats she’s had on for days. Her shiner’s a doozy, and who knows what her hair is doing. Her belly’s lumpy and loose as dough, and then there’s the baby in her arms. Not her hottest look. She tries again with, “Hi,” sliding her husky voice along the word.

Harrison shifts his eyes to the trooper. She eases down into a seat across from him like his ignoring her is no big deal. She shifts the blanketed baby to her other arm, pretending she’s not afraid of it. She asks, “How’d you score this ride?”

As if he doesn’t care how much he hurts her feelings, he looks past her.

She shifts on the seat, trying to bite back her impulse to say something sharp. “If ‘Hello, Mikey,’ is too hard, you could try, ‘Hi.’”

He puts his finger to his lips to shush her.

She’s wearing a pad for the bleeding, and her feet don’t reach the floor. She’s always wanted him—the kind of want that makes her ears ring. No bells now.

He’s wearing a combo of tired plaid and desert camo, which isn’t like him at all.

“Why aren’t you talking to me?”

There’s something more about Harrison than his fine looks, his open face. He never talks much—you get the feeling he is holding something back—but when he does speak, he means what he says. Ever since middle school, in her mind, he’s been a prince, separate from the rest of the dimwits.

Mikey had felt so smoothed out and weightless at the news he’d made it home from the war in one piece, she hadn’t questioned if he was really okay.

“Did you hear what happened?” she asks.

He gives a miniscule shake of his head. He looks at his watch and out the window.

“This baby came in the middle of the storm. I was stuck in the plywood factory while the water rose.”

She waits, not knowing whether to be pissed-off or freaked out by the way he’s acting.

Harrison picks at something on his sleeve.

“What the fuck, Harrison! I could have died.”

He whispers something so softly she only catches the words “bird” and “recon.” His usual smell—wood smoke and salt—has turned acrid. He pretends he is tying his boots, but studies the trooper.

The motor chokes to a start and the baby jerks and begins to cry. Harrison throws his hands up over his ears.

A baby’s cry isn’t anything cute. More like a cat having its nails pulled out one by one. There’s a tiny tug inside her boobs, and milk soaks through the front of her T-shirt. She shakes her head and says, “This is something no one told me about. They did not say, oh and by the way, when the baby cries, your breasts are going to flow with actual human milk that sours the second it touches whatever you’re wearing.”

The trooper steps to the front of the helicopter, flips a switch, and speaks to someone out the window. He doesn’t look old enough to drive a car.

Harrison stands and lets his hands drop. While the blades chop the air, warming up, or whatever they do before take-off, he begins to move his head really slowly, scanning with his eyes, like someone doing tai chi, until he faces the open door with his back to the guard. He raises his eyebrows at Mikey and signals with his fingers, catcher to pitcher. He waits for her… to what?

She laughs a little, knowing it’s wrong but not knowing what’s right. “You’re scaring me.”

The National Guard, the one who looks too young to shave, slips between them to rummage in the back. Sitting on a little jump seat, he changes his socks. The smell of his feet mingles with diesel. She breathes again when he’s laced back up. He asks, “You know the best brand of socks, ever?” He pulls his pant leg up from the knee, and while he says, “Darn Tough, for sure,” Harrison hurls himself out the helicopter door into the horse pasture. The trooper jumps down after him. Harrison is fast. He runs around the tail where she can’t see him. There’s nowhere for him to go in that direction, except into the bursting river.

She slides her fingers over the baby’s nubby blanket. Ashley Winter had said Harrison was having trouble adjusting, but Mikey had thought Ashley was just explaining away why he hadn’t phoned her.

Other vets come into the bar where Mikey works and they drink until their sadness turns mean and they start to fight and their buddies have to drive them home. But when Harrison drinks, he gets sexy and quiet. The last time she saw him, before Afghanistan, he stood in the middle of the river in the middle of the night, reaching for her, his shirt glowing yellow in the light from the Dickinson barn.

The baby’s still wailing. It doesn’t feel right to look at the little thing. She wasn’t ever supposed to see it in the first place. She was supposed to pop the baby out into its mother’s arms at the birthing center in Manhattan, they’d hand Mikey the last check, someone would wheel her to the front door, and that would be that.

Two National Guards, one with the tatts and the young one with clean socks, dump Harrison back in his seat and clamp him into his seatbelt. He closes his eyes, breathing hard. They’ve bound his wrists with one of those plastic zip ties that cinch tight. Junior says, “You doing okay, buddy?” He slips another zip tie through to hook Harrison’s hands to the armrest. “Our ride to Hanover will be easier this way. Their in-patient unit’s the closest.”

Handcuffs humiliating the man she fantasizes about? Now, she’s crying. She wipes her eyes quickly and says, “And oh, that’s another secret no one shared: after you have a baby, you boo-hoo at anything.” That morning she’d cried at a muddy plastic kiddie car tossed up on the riverbank by the flood—and again, at the taste of toast.

Harrison looks at her quick and away, like he’s testing to see if she’s still here.

She asks, “Why are you being airlifted?” And then she wants to suck her question back in like nothing but breath.

He doesn’t look up.

Junior swings around to face front, and the tattooed guard pulls the door into place and jumps into the pilot’s seat. The Blackhawk’s gauges blink red and green like dragon’s eyes. It’s a good thing Junior isn’t at the controls. She tries to concentrate on the pilot testing the throttle, pressing buttons, scanning the view. There are way too many instruments and dials and levers. Everything should be a lot simpler. The side of her face throbs suddenly, and she’s nothing but one mega-bruise.

The helicopter lifts, and for a second, she’s looking at grass. She grabs the seat with her free hand. The air bangs on her eardrums. They level off with a swooping motion and follow the river. She wears her neck out twisting to look out the window. What a motherfucking mess.

Plastic bags and strips of Tyvek and clumps of long grass hang from branches and phone lines above the river. How could the water reach that high? Yanked-up trees, snagged on boulders, have toppled like carcasses along the banks. The chopper swings over a low shingled roof, and it dawns on her that she’s looking down at the Mooselips Lounge where she works, and the parking lot is a mudflat shining in the sun. A house juts into the air where the force of water has taken the bank out from under it. Grasses combed flat hold busted porch railings and boots and gas cans and a lawnmower. The ruin goes on and on: whole stretches of roadway crumpled, bridges missing.

The baby caterwauls like the worst bluegrass. The noise cuts right through the chopper’s drumming. Mikey tries bouncing the baby in her arms.

Harrison slouches in his seat across from her, frowning at the floor. In high school he won the Good Citizen Award every year. He once told her he’s part Abenaki, and she can see it in the planes of his face. She remembers back when she still had friends, and Harrison pulled her into a coat room at Holy Trinity to say, “Probably better for a bridesmaid not to chew bubble gum in church.” He’d offered a tissue for her to spit it into.

They lift away from the wreckage in the valley. The mountains bunch up below as green as ever, like the storm never happened. They fly over Dickinson Farm where a tractor, like a toy, moves through the flattened gray cornfields. Her breakfast is in her throat—maybe because she’s swinging around who knows how many feet in the air with a baby that won’t shut up, and maybe because the poor guy who hit her in the face is probably driving that tractor. She’d lied to him. She hadn’t even let him know the baby came.

“You got any gum?” Mikey shouts to Harrison.

He kicks his feet out. “Are you going to feed your baby, or do I fucking have to?”

The baby’s red, like Mikey can see exactly how deeply pissed off it is. She was never supposed to have to feed this baby.

Harrison has his eyes on Junior. She doesn’t care about Junior—he is looking out the front anyway—but it’s weird to pull her boob out in front of Harrison. The last time she’d been with him, it hadn’t been any baby she lifted her shirt for.

The worst part is that she has to look at its face, the baby’s face, if they have any chance of making it work. After a few awkward tries, the tiny mouth latches on. She isn’t a bad looking baby. She’s shaped like whoever. She met the baby’s parents only once and didn’t really notice their looks, just their fancy-ass clothes, designer shit.

Mikey had pictured delivering the baby in the hospital like she was supposed to as a little reality show. She’d meant to look at the baby just long enough to know it was alive. It would be mottled and angry, like all babies, like something that needed airing out. There would be papers to sign. And then she’d have her new start in her back pocket.

She can only guess what will happen when they land. Nurses will check them over, but is there a bus near the hospital to take her to New York?

It isn’t warm in the helicopter, but Harrison is sweating so bad it drips into his eyes, and he can’t wipe them with his hands locked up. Mikey clicks open her seatbelt and crosses the aisle to plant herself next to him. She wipes his face with a corner of the baby’s blanket. All trussed up in handcuffs and seatbelt, he keeps his eyes on Junior, who says, “Hey! What are you trying to do?”

She says, “Mother of God, I’m just wiping the sweat off.”

“Please buckle up, ma’am.”

Harrison says, “It isn’t right. Breaks all protocol.”

Is he talking about being cuffed, or her wiping his face, or her deal with the baby? Is everyone in town talking about her? Is this whole baby thing just the latest showing of Mikey’s very fine fuck-up skills?

Harrison’s knees bounce like he could tip them all out of the air. She puts her free hand on his leg. The last time she’d been with him was one of those rich chunks of life that don’t happen all that often, at least to her. She’d memorized every minute as she lived it. The truth is that they grew up in the same little podunk town, but where he comes from, a man respects his mother. And where she comes from, respect is a word hurled by the assistant principal suspending you for hooking up in the back stairwell. Harrison lives with his parents who raised him to go to college, work hard, and serve his country. He has always seemed so pure, like a beautiful animal.

“They have to release you,” she says. He squints his eyes tight and makes a painful choking noise. She thinks he’s going to hurl, but his face crumples and his shoulders shake.

She yells over the noise to the guard, “Hey, could you free my friend’s hands?”

“No can do.”

“I know this guy. He’s a US Marine.”

“You don’t know the half of it, ma’am.”

“This man recently came back from serving his country in Afghanistan. Which I doubt you could find on a map.”

Maybe because she hasn’t pulled down her shirt, Junior is memorizing the view out the front of the chopper.

“Aren’t you supposed to be helping?” Fixing her shirt, she tells Harrison, “This guy did nothing but play it safe in the hills of home, a big weekend warrior while you were over there risking your life in that horrible place every minute of every day, and the fucking idiot can’t show a little respect?”

She catches sight of something reflected in Harrison’s eye, and knows it must be herself in miniature—an irritated gnat of a woman on a bad-hair day. She isn’t queen here the way she is at the bar, sashaying outside for a smoke no matter what man is waiting to have a pitcher filled. She isn’t who she was before. The sorry-ass truth is she isn’t the woman she was that last night before he shipped out, when they waded in the river and she was sure she had a chance with him. Now, she would have bounced a diabetic off the helicopter just to trade the baby for a check.

“Harrison, you got a cigarette?” She’s had like three since the dipstick turned pink. That’s something to be proud of, isn’t it?

His nose is running. He slumps to the side like a bag of sand.

It just about rips the stuffing out of her to see him like this. The noise of the Blackhawk’s blades cutting the air goes on and on. The baby squirms and bleats. Maybe she isn’t holding her right. The baby’s eyes close again, disappearing into the puffy creases in her face. She smells sour—in a good way, sort of.

Harrison had been gone for a month when she decided the best way to get ahead was to have a baby. She’d screwed everything up with everyone she’d ever known, pissed off, one by one, the people who’d been her friends, said the wrong thing, been selfish, made the wrong choice so many times, and all she could think about was ways to take her well-deserved bruises and start over.

She could not spend the rest of her life in the valley, tending bar and cleaning houses for people who couldn’t stand her. Those people had their own cars and trucks, owned their homes, or if they rented, they didn’t get evicted— a skill that seemed magic to her. They had friends. They had families, and framed photos on their mantels to prove it. They had mantels. And what did she have?

She had a smart mouth and one friend, Ashley, who was kind of a cow.

She saw what happened when life turned slippery and slid out from under a woman. She’d served plenty at the bar: biker babes in black leather vests with poochy arms, who spent the day on Harleys clinging to the backs of bruisers; hair stylists hacking up their lungs because smoking was about all they did for entertainment; big-eyed teachers in pantsuits cloudy with cat hair; bank tellers with hair permed tight as cauliflower. Mikey had started as a bookkeeper, but her bosses were assholes who didn’t like her tone, or her vocabulary, or didn’t like the way she dressed. They called her motor-mouth, potty-mouth. Then they called her bitch and fired her.

The ad in the Valley Herald said: “Are you the one? Seeking a healthy young woman to be our gestational surrogate. Our hearts are set on starting a family. Excellent compensation.” A PO Box in New York City. She’d seen ads like this forever, infertile city people looking for poor girls where the air is clean.

These people sounded whiny and stiff—deeply rich. She had to google “gestational surrogate.”

She could play the healthy country lass of their dreams. It would mean some inconvenience, going to New York to have the fertilized egg implanted and, at the end, some pain, but she could keep cleaning houses and tending bar, and the rest would take care of itself while she slept. She could make a shit-ton of money and invest in the stock market. She would move to a warmer place. She would buy a car.

She’d decided growing a kid for someone else would be a straight-ahead kind of thing. But giving birth in a beanbag chair in a factory lunch room during a flood so bad you couldn’t really call it a natural disaster—plus this whole endless helicopter adventure that won’t even get her all the way to Manhattan—wasn’t part of the deal. She should maybe ask for more money before she lets them have their baby.

When she hands her over, she doesn’t think it will feel like, “Give us your first-born,” but it probably isn’t going to be like, “Pass the mayo,” either. What expression will she put on her face? She sees her arms stretching out with this small bundle wrapped tight in her blanket.

She tucks the stretchy blue cloth with its pink lollipops and ice cream cones tighter. The baby’s no different from her other relationships. They’ve hung out, and they’ll be moving on. She’ll pass her to the woman in the fancy suit, and she’ll smile at the husband, the couple who thinks they’re so special they can’t go on without a baby made from their own DNA.

Everything was okay while the baby was no more trouble than a goldfish in its bowl. Now she sees the baby’s pulse beating in her scalp. She could touch it.

Harrison is watching her. She imagines him saying, “I didn’t think you’d want kids, Michelle.”

He is the only person who ever called her Michelle. Harrison’s eyes look softer. She wonders what he sees when he looks at her now, other than a black-and-blued storm survivor he once spent a night with.

Before, she’s felt like he was too good for her. Maybe that’s why she doesn’t tell him the baby isn’t hers. She wants to see what it feels like for Harrison to think she could be a mother. In high school, he used to say things like, “When I’m a dad, I am going to coach every one of my kids’ peewee teams.” Harrison’s knees have quit bouncing. Maybe the baby—who lolls like a miniature prizefighter, down on her luck—has put a spell on him. Mikey lifts one of the baby’s fingers. The baby takes hold of her. She is warm, and Mikey likes her weight in her lap. “She has some kind of pull, like gravity. Or ha, maybe that’s just how it feels in a helicopter.” She says, “She’s been nothing but a pain.” Saying that seems mean. Mikey leans her head toward Harrison until their faces nearly touch. The truth is he’d be the good father coaching his kid’s Little League game, and she’d be one of those witchy mothers in the stands who thinks it’s fine to shriek at him. But for a minute, she imagines they’re a family, being airlifted to safety.

“You know when I first noticed you?” she asks. “In about second grade when your family drove past my dad’s junk yard. You were like the only kid who wasn’t an asshole to me in school. You were riding in the back of your family’s truck, wearing a jacket and tie. Seven, eight years old and done up like a little pre-CEO. Remember that? You waved at me as you passed?” That was the year her mother took off, and she wore a canary yellow tutu, pretty much day and night—and red cowgirl boots that were too small.

He blinks.

“I used to wonder what it was like to be in a church-going kind of family.” When his family drove by, she would have been fetching beers for her father’s round-the-clock poker game. The men played under a bunch of broken umbrellas, rigged to make shade between the house and the junk yard fence. Running for their Budweisers was her way to be important. “You called me Michelle, and I felt dignified.”

For months, she’s been telling herself she couldn’t wait to get rid of the baby and get her money, but some things in the future aren’t all that predictable. Like this storm. Maybe she’s meant to help Harrison and maybe the baby is part of that. She imagines him saying, “I wish I could hold her.”

“You want to hold her, really?”

Junior laughs, telling some raucous story, shouting to the pilot. They’re not paying attention. She rifles through her purse and comes up with a wine opener from the bar. “Tool of the trade.” But she can’t open the little knife and hold the baby at the same time. “Can you open it?” She holds it under his bound hands.

He manages to pry it open. Then she has to put the baby down after all, to saw at the ties around his hands and the armrest.

Freed, he rubs his wrists. The curves of his forearms are so smooth she gets a jolt.

She hands him the baby.

“How do you know about holding her head?” she asks. He makes it look easy. “Maybe you could come to Florida with me. I’m going to get a bartending job at the beach. Imagine palm trees, dolphins, and warm sun.”

He doesn’t answer.

“We can throw out our miserable winter clothes and insulated boots and go barefoot.” She can see the glinting waves. How hungry she’ll be for him. Tiki torches will light the sand pathways by the bar where she works.

They sit quietly with the sleeping baby. Maybe he’s going to be okay. She thinks about the summer night more than a year ago, before he reported for duty. That night has come to her so many times while he was gone. They’d been flirting as she closed up the bar. There wasn’t a moon. They left their shoes on the riverbank. He rolled his jeans up. They waded downriver towards the Dickinson Farm, a streetlight in the distance showing the way. That night, Harrison was drunk, but not sloppy. The water was cold enough to curl your teeth, and the rocky bottom made it hard not to fall in, especially where the river curved away from the road and left them in a blue kind of darkness.

“Michelle, I got the moon right here!” he said, and held up a golf ball he’d found in the water. The driving range was close by. “A Titleist moon to light our night.” He held it up in the sky.

They were going to fuck. They both knew that.

“We are something to behold in its glow, aren’t we?” he asked.

She was high on the idea that Harrison wanted her with him. A man’s body gives off that energy. They stumbled out next to a field, onto a beach. Trespassing so close to the farm, it would have served them right to step in cow patties. Light shone out the barn windows, reached across the grassy field, and lit up the river. The ripples looked like the backs of fish fighting upstream.

The hum of a big fan in the barn was the only noise other than cows bumping around beyond the fence. One cow stretched her head between the slats toward them. She and Harrison stood close together, and Mikey knuckled the cow’s head where the horns should have been. The cow reached her tongue out, as if she too wanted a taste of him. She licked Mikey’s arm, her tongue like warm, wet sandpaper. Mikey laughed and held the cow’s long cheeks. She kissed the end of her nose. She wiped her mouth.

Harrison took her hand and dried it gently with his shirt. He held her hand open. He kissed each finger. He read her palm with his tongue, gliding along what felt like her heart line. He followed her head line to her money line until, sure as shit, she would have emptied her pockets for him. He found her life line and followed it home.

A hill comes into view.

Junior makes his way toward the door, using the seat backs to steady himself. He sees Harrison holding the baby. “What the fuck?”

Harrison turns from him and pulls the baby’s blanket up over her face. He tucks it tight, stretching the blue fabric with its pink lollipops and ice cream cones over her head, making it look eerily like Mikey’s pregnant belly. Can the baby breathe? Harrison undoes his seatbelt. His eyes shift wildly to the door, the handle, to the fire extinguisher, to the emergency latch on the window. The baby’s need pulls on Mikey. She feels it in her belly.

Harrison starts to rise.

“Give me my baby.” She scoops her away from him before he’s standing.

Junior says, “Sit down!”

She pulls back the blanket. Mikey doesn’t know what newborns can see, but the look the baby gives her is deadly serious.

Junior stands over Harrison saying, “I gotta cuff you, dude. We can’t land with you like this.” The helicopter slows.

Harrison’s face gives nothing away. Part of her wishes he’d pull some unexpected jiujitsu move and knock the little twit off his pins. Instead, he puts his wrists together and holds his hands out.

“Behind you,” says Junior. “Until you’re safe on the locked ward.” Harrison twists to oblige.

She sits back, walloped with sadness. Harrison won’t meet her eyes.

The hospital building is marked with a big X on the roof. They hover.

The helicopter sets down without a bump, suddenly still. Junior hovers by Harrison while the pilot opens the door. There’s a rush of cool dry air. She shrugs away the hand the trooper offers her. As she steps down, the ground feels too solid against her feet.

Afternoon sunlight clobbers her. Outside the reach of the helicopter blades, she waits for Harrison. Squinting makes her bruised face throb. They are four or five stories up and looking down into the tops of trees. Everything’s clean, untouched by floodwater. A walkway leads to double glass doors. She has this idea that he and she should walk down it together like a processional. They’ve made it out together. A breeze blows and her baby tenses and arches her back. That tiny pink face grimaces. Comfort or pain? One of her baby’s pale arms has escaped the blanket. Her skin seems thin as flower petals. Maybe if a mother spends enough time with a baby, they get to understand each other.

She’s holding what the parents want. They are stupid rich. If they want her so badly, why can’t they get themselves here from New York? She wraps the soft blanket around her better. “I’ve brought you in alive. They can bring the check to me.” Mikey will plug her phone into a working outlet and let them know where they’ll find their baby. She’ll get clean and sleep, and stay here where Harrison needs her. The hospital’s cotton sheets will feel so good.

She almost misses it when Harrison dodges Junior and bolts. Unless he runs through the double doors into the hospital, there is no place for him to go but off.

Junior trips him. Harrison takes a header, no arms to break his fall. He bounces back up like nothing can stop him. Mikey’s legs tingle and go flimsy. The hospital doors burst open and a guy with a gurney barrels toward them. The trooper takes Harrison down again. He comes up bloodied. Both men are on him. They wrestle him onto the bed and strap him in. She has to go with him. Though she can’t feel them, her legs keep carrying her.

Junior steps in her path. “No, Ma’am.”

“Don’t fuck with me.”

He grabs her elbow. “Are you asking for a wheel chair?” He grips her other arm from behind. Holding the baby tight, she can’t budge. He says, “I need you to calm down.” He shouts, “We need a transport here.”

It’s as if the spirit’s gone from Harrison’s breathing body. His eyes are shut, the skin of his cheeks smooth. His muddy boots splay out over the end of the gurney. The National Guard restrains her in some kind of upright half-nelson while they wheel Harrison away.

She hangs on to the swaddled baby, the tiny heft of her. But only for now.

What Mikey can’t let go of— and won’t— is the memory of how, in the cow field, in the yellow light of the barn, Harrison took her hand, and dried it with his T-shirt. How, with his tongue, he touched, so slowly, all the reasons for hope right there in the palm of her hand.

- Published in Issue 17

HELLO, MY PARENTS DON’T SPEAK ENGLISH WELL, HOW CAN I HELP YOU? by Su Cho

Are you the head of the household?

Because I am

Calling about the census—

Dear, I need to speak with an adult

Even if they don’t speak English well.

For every call like this, my mother

Gestures wildly as if we

Haven’t done this a million times.

I’m sorry, I say back to the voice.

Just do it, just once, and I shrug, listen to my mom saying she’s sorry,

Korean, yes. She stumbles over the practiced phrase, please

Listen to my daughter

My English

No good.

Once I called her stupid for

Packing my field trip lunch with

Quick sesame rice balls even though that’s what I

Requested. This isn’t true. I called her

Stupid after she hit me for low grades in English class.

The truth is, I hated my friends

Upset over the sesame smell sprawled over

Verdant lawns of the IMAX theatre. A field trip, perfect

Weather. The expensive sticky rice, stones in my stomach.

X-rays of what I eat at home scattered for my school to see.

Yet twenty years later, I am on the phone in a different time

Zone, speaking for my mother, how we just want some accountability.

- Published in Issue 17

BELOW STREET LEVEL by Geri Modell

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

I never thought I’d move back to Canarsie, but my mother died two months after my dad and then the house was empty, and my two useless brothers wanted nothing to do with it, and when the realtor on the phone said, “Yeah, missus, the roof, the plumbing, it’s gonna need fixing,” it dawned on me that I had no other prospects in sight. My lover, Janey, was mad—because she figured out it was me, not her teenage son, smoking all her pot—and wanted me out. I had just enough cash from my last unemployment check to board a southbound bus, and so I ended up, that sweltering summer, back in the three-room house that my witless family of five had squeezed itself into for most of my childhood.

It wasn’t just prospects I lacked, according to Janey, who watched me pack. “You need a purpose, babe. Being good in bed isn’t enough.” She was in a T-shirt and panties, propped up on pillows, stretching her long legs across the sheets, pointing and flexing her right foot, then her left. I reached for her joint, but she pulled her arm away, her dark eyes daring me to try again.

During the bus ride, I rejoiced in my freedom from Janey’s moralizing. But at my parents’ house, the stench—a mix of bedpan odors, my mother’s Charlie perfume, and the onions she fried for every meal—sent me back outside the front door, where I reconsidered. I had a liberal arts degree and was the first in my family to go to college, but my imagination had stopped there. I’d been fired again from a waitressing job, this time because, the restaurant manager said, his eyes fixed on something above me, I was too rough around the edges to serve quiche and spinach salads to customers. I’d pissed off a string of lovers and scared off my friends by begging for cash too many times.

With a dishrag shielding my nose and knotted behind my head, I made my way through the kitchen and living room and into the house’s small single bedroom. Two twin beds lined the wall, end to end. A child’s voice drifted like a faint memory through the closed window over the bed where I once slept. I glanced at the other bed, almost expecting to see my mother, a bulge under the blankets in that half of the room that stayed dark all day.

In the living room, I faced a floor-to-ceiling mirror, a cruel piece of décor that magnified the room’s shabbiness. With the dishrag over my face, I looked like some bomb-throwing radical. I’d been lousy at being a daughter, but at least I’d gone to their funerals, alone with Janey in the front pew.

I kept the windows open whenever I was home, ran the two box fans I dragged up from the basement where my brothers once had pot parties, and burnt a sage stick I bought at a health food store I discovered while riding my rusty old bicycle around Canarsie to see what had changed. There were, in fact, changes. The mean white working-class neighborhood that had hurled rocks and curses at anyone dark-skinned seemed to have scattered, giving way to newcomers. Front yards once manicured tight as fists were now bushy with berries and tomato vines and blazing red flowers with upright yellow tongues. Sidewalks had crumbled and roads were rutted, voices with musical accents shouted across schoolyards. A spicy pork or fish smell occasionally floated by.

The health food store, with its potted sunflowers and bins of squash, seemed a misfit amongst the tattoo parlors and liquor stores. Even more head-scratching, given the scarcity of customers, was the Help Wanted sign posted on the bulletin board, the first thing you saw when you entered. When I asked about it, the somber, dreadlocked guy at the cash register, who turned out to be the owner, named Eddie, hired me on the spot, at twenty hours a week, a buck above minimum wage. It was better than waitressing, better than nothing, I told myself, riding home on my bicycle, my mesh bag of discounted products—beans in dented cans and a container of yogurt past expiration—bouncing in the basket.

My parents’ house sat below street level. You entered the gate and stepped down two flights of brick steps, turning right at the first landing, left at the second, and then you faced a narrow walkway made narrower by two rows of spindly hedges. Outside the front door, there was a crude wooden picnic table under a canopy. My parents would be waiting there, on the rare occasion of my visiting. Descending those stairs now, holding my bike’s handlebars, I saw them at the table, my mother with her manic grin, my father—always in a tweed cap, no matter the weather—lifting his pipe in greeting, a gesture almost celebratory for such a morose man. My throat caught, and then they were gone.

The little house was sandwiched between a similar structure on one side—an old Italian couple had lived there, but now it looked deserted—and a house at street level, with an ever-changing roster of residents, on the other. I sat at the picnic table often, as a refuge from the lingering smell of my parents’ house, its darkened TV and mute phone. Mostly, I kept my nose in whatever book I had. When my attention drifted, I found myself looking up into the yard of the house next door. It had a swing set, a sandbox shaped like a boat, bicycles and tricycles, and faded-looking balls of varying sizes. A swarm of children bounced and crashed through the yard, crying and shrieking at an ear-splitting pitch throughout the day.

The head of household was a young woman, fleshy and pretty, with flour-white skin and fine hair that hung straight down like the hair on stick figures my mother drew for me when I was sick or bored. One day I saw the woman alone in the yard, pinning diapers to a clothes-line strung up between the chain link fence that separated us and the lone tree in her yard. She caught me watching and nodded her head. After a moment, I said, “Hi.”

“You live here?” she finally said.

“For now.”

She continued pinning up diapers.

“Did you know them? My parents?” I stunned myself by asking that. Usually, I was, as Janey once said, “more private than a private eye.”

“Who, me?” She didn’t break her stride, nor did she look at me again. “Uh-uh.”

Her name was Candy. As I soon figured out, only two of the children streaming through her yard belonged to her: a skinny girl in a wheelchair and a fat little boy who toddled around, putting God-knows-what into his mouth. The other children were dropped off in the morning and picked up at dinner time. Weekday mornings, I heard the television blasting from inside the house. Later, the side door opened, and the children tumbled down a wooden ramp, followed by Candy, who wheeled her daughter outside.

The girl in the wheelchair, whose name was Tina, had darker skin than her mother, but the same thin brown hair, cut short. She had a delicate face, obscured by glasses. Her legs never moved, and even from the waist up she tended towards stillness. Sometimes an older child could get her to toss a ball, but Tina soon lost interest and retired to her main activity, sitting at a small plastic table with the pile of books she brought outside on her lap. There was a Dr. Seuss; the others had covers with gruesome cartoon figures I guessed were Disney characters.

One Sunday morning when the house was already hot, I brought my tea and book outside. Candy’s boyfriend, Nick, a bald, thick-bodied man with ropy muscles and tattoos covering his arms, was pushing a bulky mower across the yard. Tina was parked at her little table, reading. My own book, a yellowed paperback one of my brothers had left behind, already bored me, and so I watched the little girl. It was like watching a tree, alive yet immobile. Imprisoned was what I thought, although I tried not to pity her.

Then Tina looked up. I smiled at her, hoping I didn’t seem too strange, with my unruly head of curls and patched-up jeans, a look I hadn’t updated since high school. She lifted a limp hand, and I waved. Nick passed between us with his mower and shot a glance my way that made it clear: Canarsie was still Canarsie. His look pinned me lifeless; it was the same dead-eyed gaze that greeted me the night before on a nearby corner, when I had dared to take a walk. I’d passed by a group of toughs, descendants, it seemed, of the kids I remembered from high school. They turned and looked me up and down, lingering on my boobs, which bounced when I walked.

“Slut,” one of them said, an assessment I couldn’t honestly dispute, although I wondered how they knew.

When I could see Tina again, she had fixed her gaze back on the page. I felt a connection with the girl, and I doubted anything good would come of it.

At the health food store, under Eddie’s solemn gaze, I was learning to tell tinctures from salves and fava beans from edamame. I was getting to know the customers, too. A tall, blonde man had caught my eye and made my prospects seem brighter for the few minutes he spent in the store. He was slim and bespectacled and polite in a way that seemed noble. Perhaps a male lover would keep his distance, would stay out of my soul. He looked about ten years older than me and was married, which didn’t deter me, especially since his wife, who accompanied him once, was bossy and rude and looked at me like I was a worm she’d found in her bag of organic crackers. The man’s name was Travis, which suited him. His wife called him “Travie,” which didn’t.

Eddie gave me twenty percent off whatever I bought from the store, but during those two weeks between my last dollar from unemployment and my first paycheck, I eyed longingly the bags of grapes and boxes of granola I packed up for customers, and then I found those same items and more in my mesh bag at the end of the day.

“You go home and eat,” Eddie said, seeing my look of wonder as he counted up the cash in the register. Then he pulled a few bills from the drawer. “Advance pay. Go get a nice pair of jeans.” On the ride home, I pumped furiously at my bike pedals, and the hot wind dried my cheeks.

There was a party in full swing at Candy’s house that day. Crepe paper and balloons had replaced the diapers on the clothesline. A life-sized cardboard princess held a sign that said Happy Birthday, and Tina wore a tinselly crown. On the tables, there were abandoned paper plates with hot dog buns and smears of cake, flies buzzing over all of it.

Tina was opening presents. There were dolls stacked on the grass like lifeless children, and there was a tea set and a pile of glittery dresses. All of it seemed intended for a different child. I wheeled my bicycle into its resting spot between the picnic table and the house. Why had no one thought to buy Tina a new book?

“Hold it up, baby,” Candy shouted. “Higher!” Tina held up a sequined party dress, shiny as chrome, and cameras clicked.

Once inside, I opened windows and splashed water on my face. Then I stood in the kitchen, book in hand, trying to read, but heard only the pounding bass from next door. It was the kind of music Janey’s son blasted from his room that would get Janey rocking her lean hips around until she tired of it, yelling, “Cut the cock rock, kid!” There was no backyard to escape to—my parents’ house had only a front yard. I could sit indoors or at the picnic table.

From outside, there was the bark of a dog, and I thought of Gypsy, Janey’s dog, who could catch a Frisbee like nobody. I missed the dog more than the woman, I decided. All my lovers suffocated me, like this house, the water-stained walls closing in. I pushed through the screen door and let it slam.

The barking dog ran across the yard next door, ribbons streaming from its collar. Tina called to it. “Copper. Cop-perrrr!” The dog turned. It knew its name. It looked its name, too. It was knee-high with fur the color of a penny, except for a small triangle of white on its head. Its floppy ears formed willowy triangles. It seemed regal yet kind, belonging to another place, a place better than that barren, cluttered yard.

Copper made a running leap into Tina’s lap. The girl shrank back, arms up.

“Don’t be scared,” Nick said. “What, you think I bring my baby girl a mean dog?”

Tina stared at the man, the same stare she directed at me that morning. I wondered why they kept calling her “baby.” She touched a finger to Copper’s head, then tugged his ear.

“Say ‘thank you’ to Nick, baby,” said Candy.

“Thank you to Nick, baby,” said Tina. I laughed, delighted to know the girl had that in her, that moxie.

On his way to the cooler, Nick noticed me. I was sitting cross-legged on the picnic table, watching the girl and the dog on his new mistress’s lap, delivering an occasional lick to her cheek, which made the girl do something I hadn’t yet seen: she laughed. I was wrong about Copper; he did belong there. He belonged with Tina.

“What you looking at, huh?” Nick kicked the lid off of the cooler. “Dyke,” he said and pulled the tab off of a dripping can of Miller.

Carrying my book inside, I wondered how he knew, how they always knew.

The next day, Monday, my shift started late. I sat at the picnic table and watched a storm drench the gray landscape, heard its thrum on the metal canopy, remembered the gushing streamlet that ran alongside Janey’s cabin. Once after a heavy rain, it nearly overflowed and we stripped and slid into it and screamed from the fresh, fragrant cold, our senses exploding. Why did I steal her pot, anyway?

Through my parents’ front hedges, I saw an occasional burst of color: a red umbrella, then a blue one. The storm quieted, and there was the hiss of car wheels on wet streets. The world was in motion, people going where they needed to go, a simple principle that I somehow found daunting. I was fixed in place, a fugitive.

That afternoon, while I rang up an elderly woman with an army of products she said would be good for her cat, I heard the tinkle of the door and saw, over the tops of the pasta boxes, Travis’ blonde head. I had a big smile ready, but he looked distracted.

“Can I pin this on your bulletin board?” He held a rolled-up sign.

“Sure, if you can find the room.”

The next time I looked up, Travis was gone. I scanned the store but didn’t see him.

“Hel-lo?” The woman snapped her fingers, pouches of swelling around her knuckles. She had a half-dozen bottles of fish oil I hadn’t yet rung up. I remembered Nick, kicking the lid off the cooler, and thought I knew about rage, too. I imagined sending the old bitch’s bottles crashing to the floor with one sweep of an arm, but the woman’s face wrinkled around an embarrassed smile.

“Sorry, dear, that was rude of me, wasn’t it?” My eyes teared up, and so I busied myself with the register. Then I felt something cool and dry on my hand and saw that she had taken it in hers. I almost pulled away but stopped. Instead, I shook her hand, first awkwardly, then vigorously, and we laughed.

At six, I locked the register and swept the floor, humming a song from a reggae album Eddie played a lot. I flipped the sign in the window to “Closed.” The new poster on the bulletin board, the one my heartthrob had pinned up, caught my eye.

“Lost Dog,” it said. “Has tags.” The traffic outside grew silent. “Answers to Copper.” And the photo, the triangular patch of white fur on his head, left no doubt. “Needs his medicine, weak heart.” The phone number was repeated in little tear-off sections at the bottom of the poster. I took one and locked up the store and rode home, slowly. I thought of Tina and her dog, and Travis and his awful wife and their dog, and Copper with his weak and wonderful heart. I wondered what Janey would do, and I knew, and she was right.

Tina was outside with Copper. She tossed a small ball to him, and Copper, polite and noble, waited for it to drop and brought it back. Candy sat on a chair in the wet sun, propping a bottle into the fat little boy’s mouth. Nick, hands on his hips, watched me make my way into the house.

The first call I had to make was to the realtor, to ask him to take this goddamned house off my hands. The second was to Eddie, to say thanks. The third to Travis, who would be thanking me. And the final call would be to Janey, who, I hoped, would give me one more chance.

- Published in Issue 17

TWO POEMS by W. Todd Kaneko

ELEGY WITH SUSPENSION OF DISBELIEF

Home is our name for the long dead

workshop where we keep memory alive

by fashioning new animals to stalk

the back yard. This is a two-headed cow

standing near the shed, eating everything

we thought holy. This is an ancient tiger,

sabre-toothed and wicked, his spiky tail

wrecking the patio. My dead father walks

around my house at night, fixing things

that don’t need fixing and breaking

everything he touches. This morning

the cupboard doors were unhinged,

all the kitchen lightbulbs burned out.

I blindfolded my father and drove him

to the forest’s edge and left him in a field

of wildflowers and when I got home,

he was already back—he had dismantled

the front steps and used the pieces to build

a shrine to the sky. We kneeled,

me and him and all the weird animals

we have wrought together, and we prayed

we might figure out how to remind the dead

they are dead, how to differentiate

where we live and where we are buried.

DINOSAUR THEORY

Imagine that one day I will be dying

and my son will want to talk

about dinosaurs, those terrible lizards

dessicated and deposited in the shale,

long shadows of the herd abandoned

to stone. He won’t believe the asteroid

theory because a collision between Heaven

and Earth makes too much sense

when it comes to theories about death.

Imagine T. rex watching the sky turn black,

little arms held up in vain to shield her face

from the fire and filth—she could be

curled up with her brood in a cave instead,

babies tucked between haunch and tail

for the end of days. Death awaits everyone

one day, but imagine if it didn’t—

my son and me sitting on the front porch,

beards down to our knees and looking

for something to talk about with my father.

He lifts both of us in his arms and we look up

at the sky, at birds in search of warmer weather,

at the stars beyond because old habits

are hard to break. We listen to the ruckus

in the distance—ambulances and police cars

all blasting their sirens and horns along

with the dinosaurs’ horrible song.

- Published in Issue 17

BRING NOW THE ANGELS by Dilruba Ahmed

To test your pulse as you sleep.

Bring the healer the howler the listening ear—

Bring an apothecary to mix the tincture—

We need the salve

the tablet the capsule

of the hour— Bring sword-eaters

and those who will swallow fire—

Fetch the guardian

to flatten the wheelchair,

to hoist it toward heaven:

the public shuttle awaits

the ceaseless trips to the clinic.

To the bedside manner

summon witness: this medic’s

disdain toward patients the physician’s dismissal

of pain—

And call the druggist, again, to drug us senseless—

Bring a nomad to index our debts

tuck each invoice into broken walls

of regret— Call the cleric the clerk

the messengers divine—

Summon someone collect the prayers buried

or burnt tied to stones sunk in seas

dunked underwater until all dissolves

The tickets rustle in a hat, the carnival music slows

A lottery ball spins, the carousel stops, the candy machine spins gold

Bring now the scribe. Let it be written:

There is no shepherd, no Sherpa, no moonlight guide

for these, the darkest journeys of our lives.

Who will lift the shuttle above the outposts of the living?

Who will watch it rise and rise?

Who will clear a path among all the wreckage?

Who will weave a nest for all the birds of passage?

Who will bridge the gap between savage and salvage?

Who will sing

over wilting stalks, rough husks, silk

still gleaming

like hair in a dream?

- Published in Issue 17

WHEN THE RAPIST DIES, HE IS LOVED by Anne Champion

I am not saying he should not be loved: how shameful

to try to control what makes us most laudably human—

the python love that coils, that will chokehold

against even the worst truths, until there’s nothing left to gag.

I have love for one of my rapists—the mercy is a stain

I’ve scrubbed and scrubbed. It’s permanent. I don’t wear it,

but I don’t throw it out either. When I watched

the eulogies, I stayed quiet, respectful of death’s

authority. I know better than to scream out for help

when it’s behind you, panting on your neck.

I know its lullaby too—it rocks you to sleep, cooing,

promising escape, to end all pain, to be, finally and fiercely,

loved. The rapist died and I wanted someone

to hug me. The rapist died and I looked

at parts of me that I wanted to amputate.

The rapist died and I wanted to say rapist, but the word

was censored from desecrating a sacred name.

It’s not wrong—it’s that we are too childlike

to understand that holy and horror can wear

the same face. Take me, for example:

when the apocalypse came, I split in two.

The dead girl and the survivor. I chained

my corpse to me and dragged her through my battles.

She was so horrifying that even the monsters

stayed away. The love did too. That is how I lived.

The rapist died and I want you to love the dead

part of me too. She won’t hurt you or even speak—

tongues and teeth are for the living.

- Published in Issue 17

IT CAME IN by Nancy Zafris

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

Painting by Camille Woods, a working artist based in Austin, Texas.

Read by Laura Lipson

with a yawn to the rural community of Nishigun where Chieko had returned home, a minor celebrity with her newfound American-sounding English that was more slurs and mumbles than fluency. It proved useless back in the Japanese school system she hated so much, where the written English they studied remained as incomprehensible as ever. A year in America and not a whit of improvement in the tests they forced her to take. She was no closer to deciphering cruel paragraphs written by Charles Dickens and Edgar Allan Poe. Upon her return from Ohio, her celebrity status had surged, then quickly flattened; she was close to being outed as the same old dim Chieko. She rode her bike home from ronin study, head lost in dark dreams. She rode with the other girls who for now were silent. She probably had another week before their laughter and taunts began. Kimi-chan would stand by as her friend, but she missed her American friends. She missed Hannah to the point that her chest ached, her heart.

She wasn’t thinking much about the earthquake on the bike ride home. The major damage had already occurred farther north on the island boot of Hokkaido. All eyes were evaluating the earthquake’s infrastructure damage to its capital city. Gas leaks had forced fuel outposts to be shut down, the Sapporo airport was closed, there was no electricity to soothe the August oppression. In the one piece of good news, the epicenter was far out in the Pacific where the tidal waves gamboled remotely and harmlessly like ancient forgotten gods.

When the aftermath of one of the tidal waves traveled south and intruded into the countryside of her own village of Nishigun, she barely noticed. The seawater lazed ashore without intention. It came across as a briny profusion more trapped than predatory. The ocean’s ebbing rhythms washed it backward. For a moment the water retreated, before it righted itself and calmly advanced.

Chieko watched it from atop a hill. It was soothing.

The surf lapped forward toward the bridge. The water level remained low. The cars on the bridge had jammed, and now celebrating guests returning from a wedding had gathered at the railing. There appeared to be no danger of the water lurching upward to sweep them away. The earthquake was over. The aftershocks were over. And this little tidal wave had turned into a sightseeing opportunity.

Chieko observed with a confused wonder. Finally to see a tidal wave, this legendary creature their country was taught to fear, finally to see it in person. It was not at all what she imagined. Not at all like Hokusai’s woodblocks they studied in school. His blue ukiyo-e waves rose with hungry white froths like tiger claws. Not at all the mountainous water, the poems they had had to memorize, not at all Kawabata’s roiling clouds. The reality below her was a wandering pool, an infinite bath. It was set in motion by a mother ocean far away, but had become in its journey a lost child floundering about in sluggish gulps.

There seemed no chance of Hokusai’s tiger pounce with these modest swells, yet a hidden power simmered within. The undercurrent began to weaken the stanchions of the bridge. The bridge began to sway. One end tilted. As the bridge surrendered into a slide, the shocked wedding guests were poured into their newly created inland sea. The bridge pitched slowly enough that most were able to run away; an old woman in a black kimono was grabbed by a rescuing hand before slipping off. The last lucky one was not so lucky, and she fell into the water just as escape was within another step’s reach, another step she could have made had it not been for the pinched gait forced by her chrysanthemum-painted kimono; she slipped in gently, and gently she was carried along. Chieko watched her. The woman did not appear to struggle; she bobbed lightly in the water, a flower. A good strategy, Chieko thought, until she realized the body was lifeless.

Still she felt calm and protected. Months earlier she had experienced the same feeling of protection when the high school quarterback had tricked her and pulled her into an Amish barn. Before she knew it, he was at her clothes and she could do nothing but let him, frightened, then knowing she was protected by Amos and the other Amish who were coming. Jared—that was the name of the high school quarterback—and she hated him, and everyone always asked her to say his name and then laughed at her pronunciation.

She stood with her bicycle, watching the scene as it transpired below. At first, the path directly downward had been her shortest route to refuge. After a quick descent into the valley that the bridge arched over, the path tunneled inland and then straight up to safety. But safety was out of reach now. It was already too late for Chieko. She had delayed too long in her dark dreams. Her friend Kimi-chan, on the other hand, had not hesitated. She had powered the bicycle downhill, under the bridge, and with a head of steam frantically pedaled upward—her soccer legs shooting her higher into the secure hills. Chieko heard screaming as the other girls on their bicycles could not keep up with Kimi-chan. Their ankles were tickled by watery fingers; then the sea’s hand wrapped round their legs and they were pulled into the water’s embrace. The bicycles bobbed one way, their bodies another.

The wedding party escaping the bridge made a loud clacking with their decorative sandals. Chieko could hear them. She thought of Amos and the clopping of horses, the rides he had given her on his wagon. And other things, all of them done for the first time with Amos.

Cars came quietly, she thought. A speedy bicycle was soundless. The louder the running, the slower the wedding guests must be going. How loud they were on the bridge. How unlucky for them to schedule joy for this day.

The people on the bridge were waving as they ran. They were waving to Chieko. They were screaming at her to get on her bicycle. They are waving at me, she heard herself say, Watanabe Chieko, third child and only daughter. Everybody loves Chieko. Everybody wants Chieko to live. Chieko’s been to America. And she thought, I look nice in my school outfit. For a moment she was not so sad. A sadness had been drowning her. She had been living in the very water she was staring at. She had not realized it until now. Finally it had come to take her home. She bowed to those she had harmed. She asked Hannah for forgiveness; she cried it out loud. She loved Hannah and wished Hannah loved her. Hannah protected her but wouldn’t say that word. Chieko loved that English word love, she said it all the time and drew hearts for Hannah that said love! love! love! She couldn’t say love to Amos though what they did must have been love. She called to Amos to remember her. She touched at the spot that had not yet grown, but she could not find its life along the flatness of her stomach. It was better this way. Her family would never have to know.

Fly! someone screamed.

In a leisurely undulation the bridge completed its tilt into the sea. Chieko was, for the moment, still perched above the water. The only path forward stayed at this height but no higher, and it ran parallel to the coast. Riding further inland meant the scribble of hills and all its ups and downs. Already the trough of her first descent was filling with water. The water was not yet dirty, Chieko noticed, so new was it to this green land. It had not had time to find the dirt underneath.

Fly! someone screamed again.

It was a real voice. Was it Hannah’s voice?

In the puddle of a descent flared something golden. She jumped on her bike and rode toward the glowing beacon. Fly! screamed the voice again.

- Published in Issue 17

DON’T TOUCH MY JUNK by D. A. Powell

I strip

for tips

it’s pits

it’s hit

or miss

you sit

unzip

and spit

on it

but it’s

a trip

my trick?

I’ll piss

I’ll shit

I’ll fist

yr dick

I’ll lick

yr lip

till bit

by bit

yr sick

of it

I quit

at six

let’s fix

let’s sex

be quick

who’s next

so thick

I’ll rip

- Published in Issue 17

- 1

- 2