SONG FOR AMERICA by Jacques Viau Renaud trans. Ariel Francisco

America, sitting atop the night’s shoulders

singing in the faces of the hungry

deciphering the language of sadness

measuring the modulation of hatred in our children’s stomachs.

America, they’ve stolen your joy

destroying the muscles in your face

tied your heart to the vigil

where thousands of beings wander

inhabited by death,

a death we drag since men, from beyond,

buried his sword, before your name on this earth.

And the dirt

and the mold

and the mud

of our sun-threshed life.

America, get up America

shake off the dust and rust inside you.

America reborn

reborn America

American men,

American women and children

listen to the tremor rumbling from the Antilles

from that stone peak giving birth

to the voice of a child singing from a tiny island

from the hammering of the scaffold

whose shoulders are built from the blows of cackles

and courage

the pure orb of “American love.”

Listen

a new howl fills the sails of America

dragged by the enemies of man

capitalists,

proxies of the temples and Bibles

in the courts of peace and death

so the truth does not burn Bolivia into thirst,

strangled with a clay cord

the heir of the Inca’s

dead on an eternal bonfire

so the light won’t awaken the sleeping quetzal

atop the ruins of aboriginal silence,

to Chile, long and vibrant,

a spear pierced through the heart of an Araucanian;

to Central America

massacred by dynamited bananas,

to Venezuela

where the capital houses their steepest gallows

and the hosts of love are an impenetrable bastion.

To Brazil with large land and few people

adorning their rags with diamonds

tears on the soldiers lapels

while in Argentina and Paraguay

blood clots hang from the commanders medals

and from chimneys rise the stench of crushed meat.

Oh America!

Now without sail

without compass

bent from hunger

bitter fruit fallen

from a shadeless tree

under whose ruined structure

the American licks the back of sadness.

Oh America!

Piece of the dissected chant,

America, America,

reborn America

burdened men of America

light your bonfires

and march towards the light that guards history.

March

inheritors of blood

Colombian cowboys

with their enormous stomachs

where sunflowers bloom.

Natives of Peru

and Ecuador sleepy with coca

raise the ancient face of purity

and tell your secrets.

And you, Puerto Rico

nailed to the jaws of hatred

small lump of sugar plagued by vermin

slow assassination

crushed between masses of metal and glass.

Oh Puerto Rico

I love you more than any other American homeland

because you permanently inhabit the cry

I love you

I love you

I love you from Santo Domingo

dismembered corpse

shout parted in two

but born of a single throat

from a single anguish,

alone.

Oh America

piece of the dissected chant

with a luminous morning

built by the guerillas of love

who have their widest smile in Cuba.

Oh America

for you so many men fight

for you they die

how much love must be housed

to die for you

for an America not yet born

and won’t be for some time.

Americans of the new gospel

hold in your hands

our heart’s clamor

raise high our cry

tighten the knots that tie us to tenderness

the infant dawn of a smile

tied with your veins

wet with your blood

purified by your cry.

Americans of the new gospel

raise high our cry

so it survives the flood

because it will give birth to generations of happiness

an ample mankind

large as the smile of the proletarian sunrise

forever seedlings of vigor

of spilled love

while life edifies

over the debris of a past life.

Americans of 1963, of this century

evangelizers of the new world

raise your heads

raise them high

to see from afar this land that constitutes our future.

With our remains:

with our hands and bones

with our organs,

with all our being,

with this burdened life,

built to survive,

see it

and do not faint

because we are tomorrow’s fire

the eternal youth

the gesture of those who love

giving everything

taking everything

for this life submerged in your voices.

Jacques Viau Renaud (1941—1965) was born in Haiti and raised in the Dominican Republic following his father’s exile in 1948. During the Dominican Revolution of 1965, he joined the rebel forces in support of ousted president Juan Bosch, fighting against the US backed dictatorship. He was killed in battle at age 23.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

THE PIER by Judita Vaičiūnaitė trans. Rimas Uzgiris

Your torn white shirt lies

drying on the anchor.

In the hush of my cheek

I feel your gypsy hair, while husky

voices echo across the water

and through night’s rusting gear.

Palms timidly touch

the still aching secret scars.

Dawn breaks, and in its light

I can see your heart in your eyes,

waiting for me like treasure received…

O dawn – of boundless brutality and beauty!

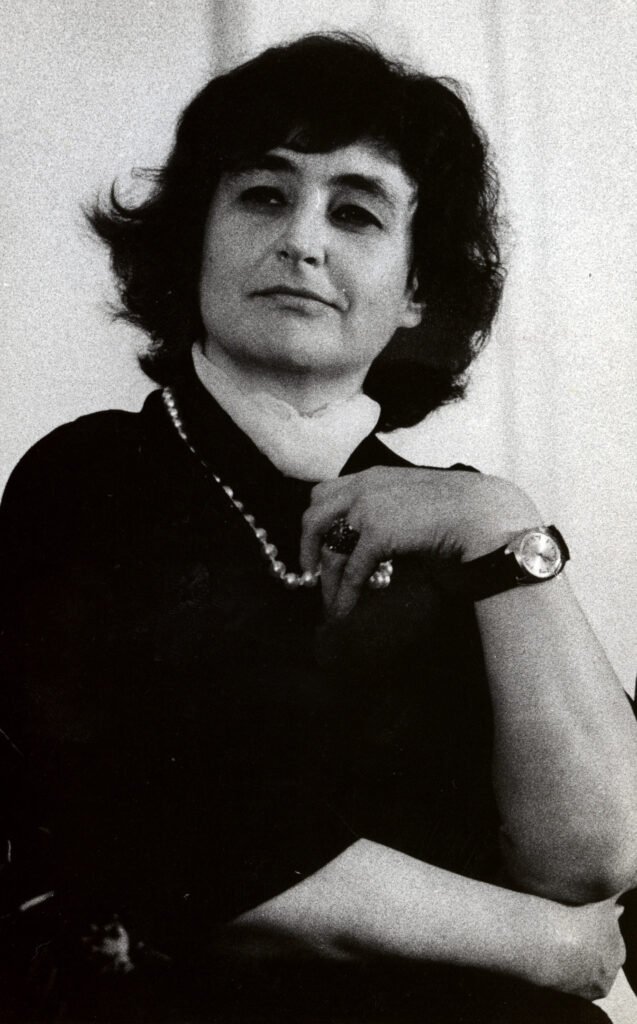

Judita Vaičiūnaitė (1937-2001) was one of Lithuania’s leading poets of the second half of the twentieth century. She graduated from Vilnius University in 1959, and spent most of her life in Vilnius. She published over twenty books of poetry, as well as translations of poetry, poetry books for children, and plays. She worked as an editor for several leading literary journals in Lithuania. Her poetry has been translated into English, German, Russian and other languages. Shearsman Books (UK) published a selection of her poems in 2018: Vagabond Sun. Her work has garnered numerous prizes, including the Lithuanian Writer’s Union Prize in 2000, and the national award of the Gediminas Cross in 1997.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

TWO POEMS by Stefano d’Arrigo trans. Joe Gross

WHEN MEEK & THUNDEROUS

When meek & thunderous

spring makes its mooring

& the heart wanes in wax,

honeycomb homilies

flit from fin to wing

of migrant fish & birds

wearing whispers of your name;

we imagine you, because it’s true,

your destination, too, is mystery.

OH IN ITALY A MEMORY

Oh in Italy a memory of the women

who turtledove-strut the windowsills

suddenly thresh their thighs

pulverizing poppies in secret

red petals of their Saracen dresses

fluttering like lustful oriflamme

in defense of the footsteps scrawled

over the island’s wind-worn cobbles.

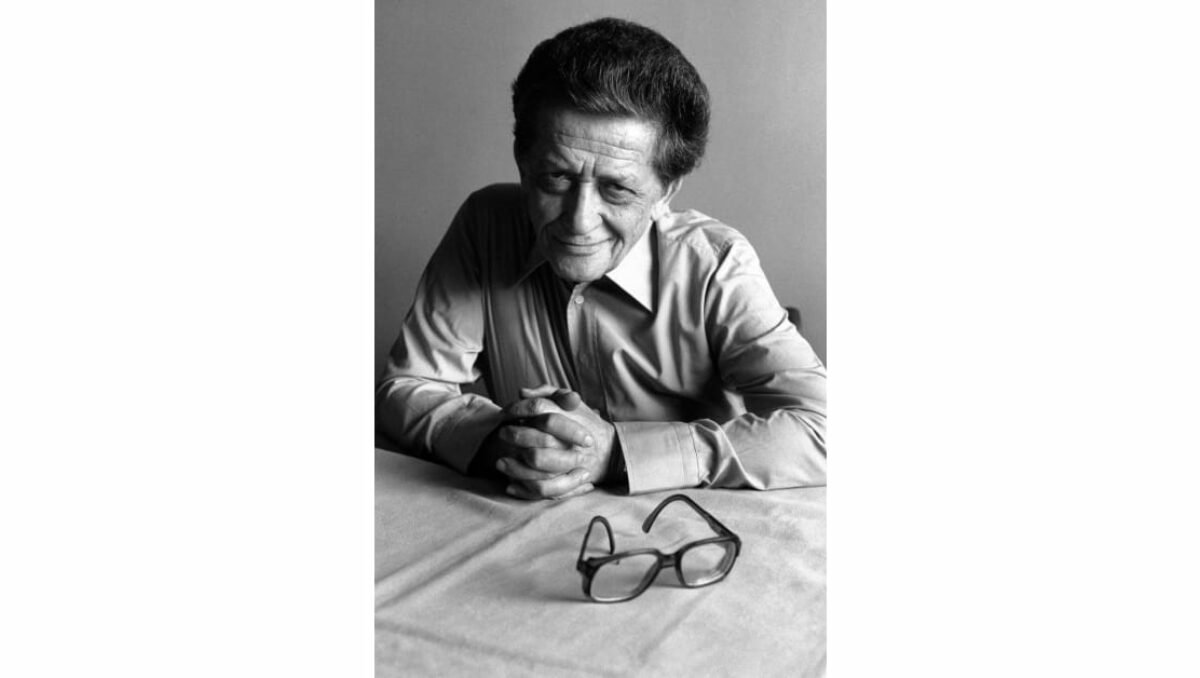

Stefano D’Arrigo (b. 1919, d. 1992) was born and raised in Alì Terme, Messina, Sicily, but lived and worked in Rome as an art critic much of his life. He is the author of the poetry collection Codice siciliano (Sicilian Code, 1957), the epic Horcynus Orca (1975), the novella Cima delle nobildonne (Noblest of Noblewomen, 1985), and Il licantropo e altre prose inedite (The Lycanthrope and Other Unedited Prose, 2010), and played a minor role in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 directorial debut, Accattone.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

RADISH FLOWER by Jang Seoknam, trans. Paulette Guerin and Claire Su-Yeon Park

Is a path one travels alone also a road?

The radish flower has bloomed

along a hidden path

after others have been planted.

In the swamp, the radish flower has bloomed

without a flag,

without a flagpole,

its heart coming alone,

late spring arriving with only its body.

Woo woo. Like a Molotov Cocktail,

I bloomed late, among the radish flowers.

Roads ahead and behind are blocked by blue barricades of grass and trees,

at the place of the sacred late spring.

I lived a few breathless days

along a road going alone.

Is the road no one walks

a road too?

My yellow pollen

going somewhere in late spring.

Claire Su-Yeon Park, a nursing decision scientist and poetry enthusiast, wove her research journey into three published poems in healthcare journals. Her poetic inspiration is now fueling her groundbreaking interdisciplinary research, illustrating how the poetic imagination inspires creativity in the age of artificial intelligence—a muse for scientific innovation.

Paulette Guerin lives in Arkansas and teaches writing, literature, and film. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Best New Poets, epiphany, Carve Magazine, and others. A suite of 25 poems appears in the anthology Wild Muse: Ozarks Nature Poetry. She is the author of Wading Through Lethe and the chapbook Polishing Silver.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

TWO POEMS by Beatriz Pérez Pereda trans. Colleen Noland

“Untitled”Lucía nursed her anguish for thirty-six years (she didn’t know sadness is an animal that doesn’t understand flattery). There are no pictures of her: she was afraid of the eye in the camera lens, since it was said it could bewitch a soul and make feet clumsy on cliffs. Everything about her is a fable—she could have had six fingers, a third eye, been bald and missing teeth. Or, as some say, she could have been more beautiful than a quiet death—no evidence exists to disprove it. They say she got up and changed the curtains, and her hair was enough to make you love her. They say she was silent as water that watches over dreams of the drowned and her dresses seemed to anchor her to the journey she started as a child. They say she emptied her glass, listened to what her legs demanded. They say the animal praised her, caressed her, in return. I was almost named Lucía. Lucía was my grandmother. “Untitled”A dream: the sea, a port, perhaps the same one where my letters don’t arrive because I don’t know its name. A tiger comes towards me with the remains of a blue deeper than the white-water’s whisper. A tiger carrying a drowned girl’s nostalgia on its fur. A tiger without hunger, waiting to see in my eyes the chains and fire he confuses for home. I approach, and maybe the fear of the salt waves crystallizing or the clouds cacophony make my movements small. I approach, and suddenly I know, by instinct: the tigers are oil paints of water, streaked with fury, mirrors that confess before other tigers. |

Beatriz Pérez Pereda, (Mexico, 1983). A poet and member of the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte de Mexico, she has received the following awards: the Carmen Alardín National Poetry Prize 2022, Óscar Oliva Poetry Prize 2022, Dolores Castro Poetry Prize 2021, Amado Nervo National Poetry Prize in 2015, among others. She has published several poetry collections: Persona no humana, CONARTE, 2022; Crónicas hacia Plutón, ITAC, 2022; Habitación en sombras, IMAC 2021; Teoría sobre las aves, CECAN 2018; Los sueños del agua, Instituto Municipal de Cultura de Toluca 2013 and La impaciencia de la hoguera, IEC, 2010. She currently teaches poetry workshops and conducts interviews with writers for La Gualdra, the cultural supplement of La Jornada Zacatecas.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

MOTHER TONGUE by Adil Tuniyaz trans. Munawwar Abdulla

We were born like gold

on this sparkling brown land.

It fell, ringing

from the mouth of an Uyghur angel,

its music sunk into our ears.

Oh, mother tongue,

we became wanderers,

and have moved far from your horizons.

Opium poppies

bring the scent of the seas,

thoughts kept moist for a while.

I have left the radio on.

It speaks

in the wind.

Cool orchards

Oil, sandy mountains

A group of people whose colours have drained,

dead still cities and winter pastures.

I drank coffee

and cried.

The ocean waves entered my home.

A note on Adil Tuniyaz by Munawwar Abdulla

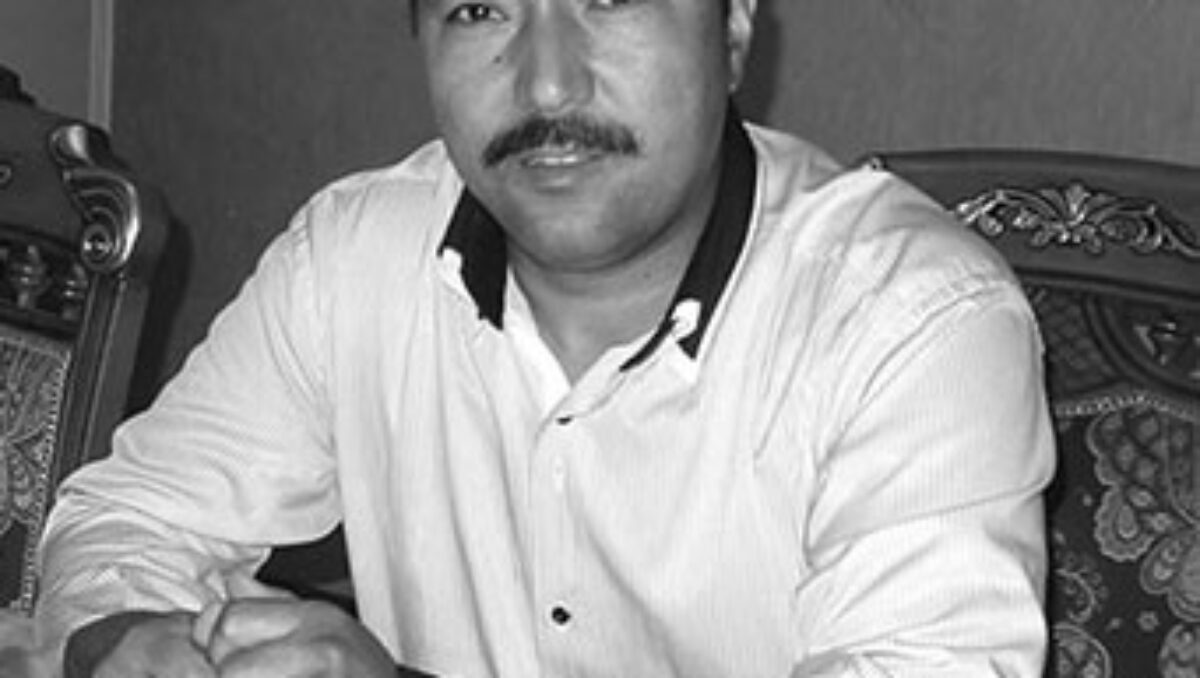

The current whereabouts of Adil Tuniyaz is unknown. Most likely, he is in a jail in Urumchi, the capital of occupied East Turkistan, in Xinjiang, China.

Adil Tuniyaz, his wife Nezire Muhammad, eldest son Imran, and father-in-law Muhammad Salih Hajim, were all arrested in December 2017 during the Chinese government’s mass incarceration campaign that displaced millions of Uyghurs into re-education camps, prisons, and forced labor factories. The official charges for Tuniyaz and his family’s arrests were “promoting terrorism and religious extremism”. Multiple sources have speculated that the family were detained for their work translating religious texts such as Islamic hadiths into Uyghur. Muhammad Salih Hajim was a prominent religious scholar who was credited with being the first to translate the Quran (with permission from the government). He was confirmed to have died in a re-education camp in January 2018. It is difficult to know the current status of the rest of the incarcerated family.

China has denied the existence of “re-education” camps, then rebranded them as vocational training centers, then defended them as deradicalization training, and now claims that they have closed. Still, the number of prison sentences have skyrocketed, and many of those camps have always been attached to forced labor factories. People from every age group, religion, career, or academic background were targeted with no opportunity to ask for evidence for arrest or appeal for release.

Along with the crackdown on bodies, there has been a crackdown on thought. Knowledge. Language. Many writers, artists, publishers, even literature and anthropology professors, have been given long prison sentences for vague reasons with no trial. Tuniyaz’s cohort of modernist poets included Perhat Tursun, a controversial and secular writer who is now serving 16 years in prison after being arrested in January 2018 for unknown reasons. Another is Tahir Hamut, who managed to escape to the US and write about his harrowing experiences as an artist navigating state control in his book Waiting to Be Arrested at Night (2023).

While we wait to hear of Adil Tuniyaz’s fate, it feels important to share his old poetry. We sink into the softness of his longing for familiar sounds and horizons while in a foreign land. We think of his connection to identity and the way he transposes Islamic mystic elements onto Uyghur cultural motifs. I marvel at the scents and melodies he infuses into his poems. And I note the irony of translating a poem called Mother Tongue, and wonder if I have become unanchored like him, and maybe I should drink coffee, and maybe I should cry.

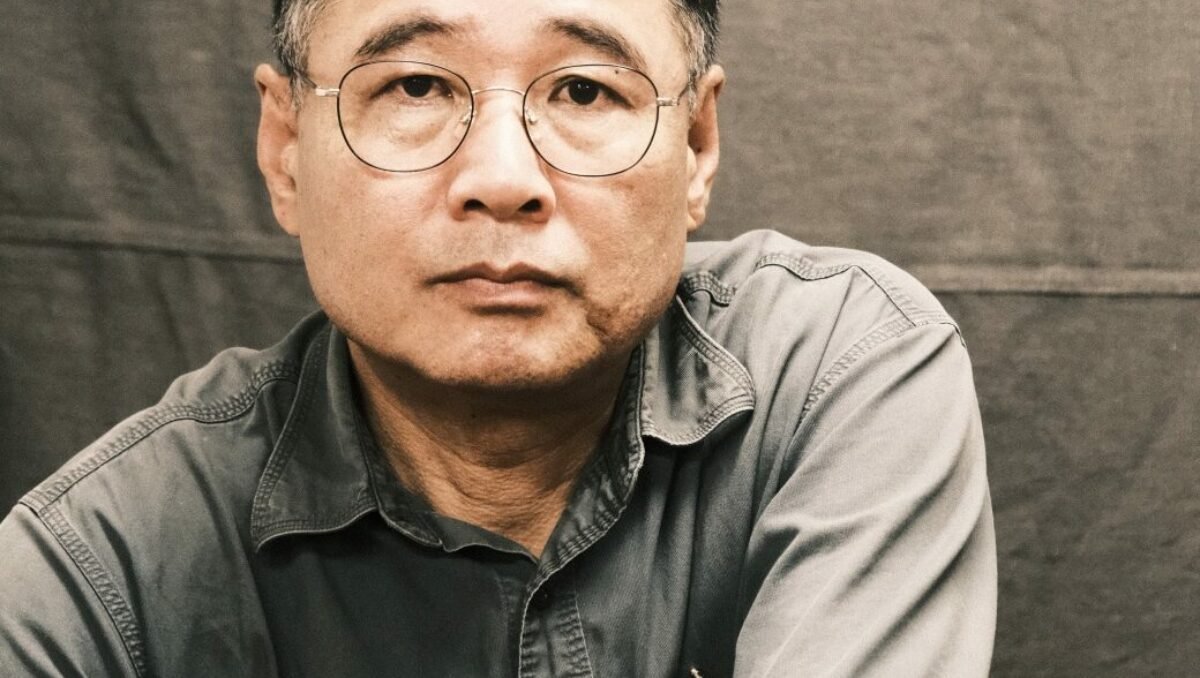

Adil Tuniyaz (b. 1970) is a well-known poet, journalist, and author of the books Questions for an Apple and Manifesto for Universal Poetry. He is often considered to be among the first generation of modernist Uyghur poets. Publishing his first poem in the journal Xinjiang Youth Daily at just 12 years old, Tuniyaz continued to pursue his passion for literature at Xinjiang University in Urumchi. After graduating in 1993, he became a journalist for Xinjiang Radio while continuing to publish his poems in literary journals, as well as several of his own collections of essays and poetry. In the late 1990s, he left his journalist role to continue his literary studies in Saudi Arabia, returning to Urumchi a decade later. In 2015, he and his wife, Nezire, opened the Light and Pen bookstore. Tuniyaz’s poetry often touches on topics such as Islamic mysticism, Uyghur culture and identity, and many contemporary themes that have made him a popular poet in Uyghur society.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

I WILL REMEMBER by Rahile Kamal trans. Munawwar Abdulla

Today I did not comb my hair

I didn’t even look in the mirror

My kitchen greeted me icily

The walls eyed each other, but didn’t look at me

I wasn’t worth it to those four walls

It’s hilarious that my cat was scared of me

Is my appearance uglier than a cat

Is it so important to dress up

How did I get to this thought

To carry on for a day like I am not living

Doing whatever that comes to mind

To think like those who have gone mad

Firstly, I boiled the coffee in a saucepan

then added a touch of vinegar

I washed my socks in the dishwasher

Found holes in four places

tossed and turned it

and sensed that it was still sound

I tried calling my daughter mum

Can you believe she replied, yes my daughter

I will remember that my mother is also my daughter

I hesitated when it was my husband’s turn

because sometimes I do not recognise him

He has this one look

where my insides end up on my outside

That is the way I am tested

I will try calling him by another name

Wallander, I called, staring at him

Wallander is a Swedish inspector

He didn’t respond, so I repeated, Wallander

Your case is fairly complicated, huh

If we bear it for a day it will unravel itself

A gourd with no water will wear holes in itself from dryness

So he said, looking at himself

Carefully combing my unkept hair

I will remember my husband really is Wallander

The litterfall is my red carpet

The trees sway and flirt

On one foot I wear a boot, on the other a slipper

I wailed loudly in my Uyghur tongue

The Ili roads are winding, winding

On those winding roads, a pair of skylarks sing plaintive

Mournful skylark

I will remember the magnanimity of the trees and litterfall

I came upon a gaunt woman

She froze upon seeing me

then backed away slowly

barely holding back a laugh

Between the two of us one of us is crazy

I know I am faking crazy

If she is also faking crazy

it’s clear then we are both crazy

After the gaunt woman

I arrived upon a four-way intersection

Green, yellow, and red lights

were brushing the road’s pressure points

Ah the highest degree of mania

It is not at all like the imagination

The lights stand around

shining their eyes

There is only colour here

The colour yellow is calm

How mystical is the red

How loving is the green

Some people would say I was calm

when they became toothless snakes and bit me

They would say I was a loving woman

when they hid the sun behind their hems

They would say I was a mystical woman

when I became crazy like this

Again a green light

On yellow we prepare

Red summons

I raised my right leg

I raised it and

I saw a woman stretched out on the ground

Her white hair uncombed

On her right foot a boot, on her left a slipper

Mournful and restless

Oh, this crazy, whining woman

said the gaunt woman

whispering

Oh, this lunatic woman

said the cat

muttering

The woman lying on the floor looked like me

but was not me

The green light was still on

I will remember the countenance of the colour green

I recalled all my memories

My vinegar flavoured coffee

My holey socks

My daughter mother

Wallander

My litterfall

My madness

These are all my green lights

Rahile Kamal is a poet born in Ghulja, East Turkistan, where she worked as an editor, reporter, and editor-in-chief at the Ili Evening Newspaper from 1993 until 2004. She was a prolific writer, publishing numerous poems and other literary works in various newspapers and magazines, many of which received prestigious awards. However, after migrating to Sweden in 2004, it was only after 2016 that Rahile rekindled her passion for writing and began publishing again in journals such as Izdinish and Ittipaq. Her poems have been translated to Turkish, Japanese, Chinese, and English. In May 2022, she published her poetry collection titled Kamal is Gone in Istanbul, and she has upcoming work in the anthology Uyghur Poems, which will be published by Penguin Random House in November 2023.

- Published in ISSUE 28, Translation

A FLOWER THAT REFUSES TO BE POETRY by Kim Hyesoon trans. Cindy Juyoung Ok

Anything too cold

does not become poetry

Anything too hot

is not poetry

Soaking your feet

in boiling water

does not bring out poetry

Lying on the ice

with eyes wide open

does not bring out poetry

That day no one wrote poetry

They just made a call

Secretly picked up the receiver

Blew and sent off poetry

—Did they wear new clothes?

—No, just took off their old clothes.

That day no one wrote poetry and

they ripped a wedding dress

to make bandages and

held rice bowls

to make coffins to contain each of their heads

Anything too beautiful

is not poetry

That day when they opened their mouths and

cried as though for the first time

that was not poetry

merely

the blooming of an entire city

floating on the field of the earth

a flower that refuses to be poetry!

TRANSLATOR BIO:

Cindy Juyoung Ok is the author of Ward Toward (Yale University Press, 2024), a Kenyon Review Fellow, and host of the Poetry Magazine Podcast. More translations from Kim Hyesoon’s The Hell of That Star are in Bennington Review, Poet Lore, and Tupelo Quarterly.

- Published in ISSUE 27, Translation

TWO POEMS by Abdourahman Waberi trans. Nancy Naomi Carlson

Sahel! Sa(y) Hel(lo)

Mother earth The gods are seeing red The earth the sea In India an old legend persists He sings of the wandering caravan driver who didn’t What remains of our oldest forebears the reptiles |

Every Being Is UniqueI’m a sponge Heaven is on earth and nowhere else You’re getting too old, son Inscribe in your notebook these expressions The sun opens the inkwell to the day The cock’s crow As a child one sometimes confides Every being is unique |

Nancy Naomi Carlson’s translation of Khal Torabully’s Cargo Hold of Stars: Coolitude (Seagull) won the 2022 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize. Her second full-length poetry collection, as well as Delicates, her co-translation of Wendy Guerra, were noted in The New York Times. She serves as the Translations Editor for On the Seawall.

- Published in ISSUE 27, Translation

THREE POEMS by Nadja Küchenmeister trans. Aimee Chor

at the base

no one quite knew how late it was

when it was too late: i came back

a breeze took my hand, the courtyard

recognized me, as always, without waking

i picked out the old names on the name plates

bein, puhahn, henke, brumm, i let them dry

no clothespins on the clothesline

where there was a puddle, no longer a puddle

where no trees stood, there stood trees

the hedge conversed with me, softly, a shadow

under the ping pong table, only the lifespan of the streetlights

seemed longer than an afternoon: mr. schatta

has slept in the graveyard for twenty-five years

for twenty-five years i have been asleep too

no one quite knows how late it is, when it is too late

benches without backrests, as always deli-counter light

the small flakes on my lips, that scrap of skin

i push around at the base of my tongue, i am.

after the conversations

it is as if your furniture had decided

on its own where it would like to stand

a circumspect silence of wood

the bed in its corner in the hall

the bookshelves, their load

mystery novels, political texts

there is nostalgia for plastic

bags near the closet i catch

a scent, harsh in its sweetness

wallpaper flakes away here and there

from the walls, where did the brownish stain

on the ceiling come from, on the dresser

a framed photo of my childhood

friends, they are still looking at you

silent and dusty: this is how one grows old.

scorpion or spider

you’re saying something about matter and dark space

and your arms spread out wide, as if you wanted

to cradle a zeppelin, stars, electrodes

voices approach, grow distant, monitors

something hisses, your lungs, and these white

machines, seductively cold, know almost everything

about you, cables, hoses, the door hangs lightly

on its hinges on a glowing hot sunday

afternoon dust motes float in the air like bird

feathers on water…we follow them

as they fall, flakes of skin fall

we do not hear the steps in the hall

until we see shoes, an animal in my back

scorpion or spider, marks the break: i could not

find a container for the teeth, i’m sorry, nor

for the toothbrush, the comb, there are more hand

kerchiefs in the bag, the phone and your reading glasses

two shirts, socks, some pairs of underpants.

Aimee Chor is a poet and translator in Seattle. Her translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Sepia, The Apple Valley Review, AzonaL, and mercury firs. She can be found on Twitter @aimeechor and at https://commonplaces.netlify.app.

- Published in ISSUE 27, Translation

INVITATION TO END by Faris Kuseyri trans. Patrick Sykes

A woman puts an orange in her husband’s pocket

and her longing I saw

they’re opening unmarked graves with warrants

and silence’s strength I saw

truth bound, the papers lie

and hate in the words I saw

grace in the bazaar, conscience in exile

and the feigned surprise I saw

driven again to my pencil’s mercy

and the invitation to end I saw

from poison mouths the children kissing the vine

and their glass bravery I saw

Patrick Sykes is a journalist and writer based in Istanbul, Turkey.

- Published in ISSUE 27, Poetry, Translation

from YOU by Chantal Neveu trans. Erín Moure

first his breathing then his pupils

I watch his mouth

its furrows its swells

slight circle of his irises

the black hole a tube

he sees me

impulsion

an implicit programmatics

ascension

the facades the borough

remanence of Rio

a yard a garden

the staircase

winding

its gradations

compelling

the maples

alongside

the false acacias

figuration of caresses

swirled rumour of a fountain

faint sound

metallic taste of the city

a magnetism

from palate to nostrils

infra-resonance

warm silver

low table

the flakes of fish

air under the studio ceiling

a loge

we make acquaintance

summer solstice alters the sky

we deflect curiosity by foreseeing questions

private

spheres

spontaneous revelation

the ineffable

freshness of a stream

are we already naked

bared

we expose ourselves

fluidity

gravity

propensity

the charm

the intimacy

premise of a banquet

Hephaistos

Aristophanes

vestiges dionysiae vertiges

Empedocles

happiness

tenor of futures put to the test

at ease

we name

great loves

inflections

decades

les fidélités

promises made

offenses injuries miracles

the enduring friendships

gaie santé

current genealogy

virtual group portrait

numerous

already

he stands up

draughts

the bamboo imbibe their fill of rainwater

transfer of delectation

euphoria

temptation reparation

congruency

catalysis

paradoxical privilege

incursion

permissiveness

we draw close

to kiss

convergence

Erín Moure is a poet and poetry translator. Most recently: Chus Pato’s The Face of the Quartzes (Veliz Books, 2021) from Galician, and Chantal Neveu’s This Radiant Life (which won the 2021 Governor General’s Award for translation from French and the Nelson Ball Prize). A new book of poetry, Theophylline: A Poetic Migration via the modernisms of Rukeyser, Bishop, Grimké, has just been published by House of Anansi. https://erinmoure.mystrikingly.com Photo Credit: E. Sampedrin

- Published in ISSUE 27, Translation