The Landlord by Peace Adzo Medie

“Asanka,” sneered Emma’s landlord, his bony frame planted in front of the staircase that led to her apartment. It was dawn and she had just returned from walking with her friend, Martin, to the bus stop. He had tutored her throughout the night, in preparation for the entrance exam that she would take in a week’s time, and she had felt obligated to see him off afterward. But now as she stared into her landlord’s rheumy eyes, she wished she had stayed indoors.

“Pardon?” she asked, hoping she had misheard him.

“If you are letting men come into your room by heart, by heart, without any care, they will use you by heart,” he clarified.

“Mr. Dadzie, Martin is an old friend,” she said as she squeezed past him to climb the tiled steps.

“The mouth of an old man might smell but it does not mean his teeth are rotten. You do not like what I am saying but it is the truth,” he called out loudly after her, so loudly that his second wife, Akos, looked up from the basin over which she was hunched, washing her baby’s diapers.

Emma sucked her teeth as she stepped into her living room, but her anger couldn’t keep her upright. A few minutes later she was sleeping so deeply that even the piercing calls of the passing porridge seller could not wake her.

She had rented the two-bedroom apartment in Accra from Mr. Dadzie, a retiree, a month before. She had had to move out of her parents’ house in Tema because she wanted to be near the supermarket, where she had just been promoted to floor supervisor. Instead of the two-hour bus ride, it now took her about thirty minutes to get to work. She hadn’t rented the place because she fell in love with it but because it had been newly renovated, was affordable, and was in a walled compound. She occupied one of two apartments on the top floor. A primary school teacher and her family lived in the second apartment. Below them was Mr. Dadzie’s house, which he shared with his two wives and three of his seven children.

She had found the place through Mensah, one of her coworkers who moonlighted as a real estate agent. At their first meeting, Mr. Dadzie looked pointedly at her unadorned ring finger and asked her if she was married. She told him that she wasn’t.

“Ah, what have you been doing?” he asked, his forehead scrunched up in bemusement and his mouth turned down in disapproval. They were seated under the crooked branches of the lone almond tree in the backyard and behind them, Auntie Yaa, his first wife, had been pounding palm fruits in a small mortar. Mr. Dadzie had not introduced her to Emma and she had not lifted her eyes from her task to look at them.

“I’m only twenty-five,” Emma had said, swallowing the sharpness that threatened to rush out of her mouth and spear the man. He was older than her father and thus, in her eyes, deserved her respect. Also, she had been searching for four months and this was the nicest place she had seen within her budget. She, therefore, couldn’t risk angering Mr. Dadzie, who had sighed heavily at her response, causing the long white hairs poking out of his nostrils to flutter like tiny flags.

“Where are you going to get the money to pay me? You know I’m asking for two years’ advance?”

“I work.”

“Doing what?”

“I’m a supervisor at Shop Well,” she said. She had not added that her parents would give her most of the money because she didn’t earn enough. Mr. Dadzie sighed again and glanced down at his smartphone. When he finally met her eyes, he looked pained, as if her lack of a husband was causing something inside him to hurt.

“I do not want you to be bringing different, different men into my house, today Peter, tomorrow Paul. In fact, it is because of this that I rented the other apartment to a married couple.”

“Okay,” she replied, impatient for him to stop talking and show her the lease agreement. Besides, she had dated her last boyfriend since secondary school; she had never been the type to have a parade of men marching through her life.

“Do you have a boyfriend?” he asked.

“No.”

“Hmmmph,” he exhaled.

Exasperated by the man’s questions, Mensah had lifted his fake Ray Ban off his face, turned to Emma, and rolled his eyes. “She’s not troublesome,” he said to Mr. Dadzie, anxious for his finder’s fee. Emma moved in a week later.

A month after sitting for the exam, she found out that she had passed. She was ecstatic because it meant that she could enroll in the management program at the Catholic University. She liked working at Shop Well, but wanted more. To celebrate her success, she, Martin, and six other friends drove to a riverfront resort near Akosombo. They made the trip squeezed into Martin’s mother’s SUV because none of them owned a car and they didn’t want to be seen arriving at such a posh venue in taxis. They spent the day ordering dishes that cost more than their weekly food budgets and riding small boats on the Volta River. They enjoyed themselves so much that when returning home, the snaking traffic on the Tema Motorway didn’t even induce the usual groans.

In front of her apartment, Emma thanked them for celebrating with her and stepped over the tangle of legs to exit the car. A happy grin was plastered on her face as she neared the gate, but it disappeared when the ten-foot high metal sheet, lined with spikes, didn’t budge at her push. She tried a second time, but all she got was a sharp groan as the rusty hinges shifted slightly. She realized that the gate was locked from the inside.

“What’s the matter?” Martin called from the car.

“The gate is locked,” Emma said.

“Oh, how?” he asked, stepping out.

Emma shrugged. This had never happened before. But then, this was the first time that she had come home at ten. For the two months that she had lived there, her life had revolved around work and studying for the exam. She returned home at six on most days and spent her one weekend off in the month sleeping. Martin rapped his knuckles against the gate and they pressed their ears to the cold metal and listened for footsteps. After five attempts, no one had come to let her in. When Emma looked up, the light was on in one of the teacher’s bedrooms and a figure was moving behind the curtains. There was no way that the woman could not have heard her.

“Call the landlord,” Martin suggested.

Emma nodded. She hesitated but then fished her phone out of her purse and dialed Mr. Dadzie’s number. He answered on the first ring.

“Who is this?” he growled.

“Mr. Dadzie, please, it’s me, Emma. The gate is locked.”

“And so?”

“Please send one of the girls to open it.”

“Do you think my children are watchmen? Was there a security guard on duty when you left this morning?”

“Please, I need to enter.”

“You should have thought of that before you stayed out gallivanting,” he said, before the line went dead.

Emma’s face hardened. “This man paaaa,” she said to Martin, shaking her head, “locking me out of the house where I pay rent.”

“You can stay at my place, my mother won’t mind,” Martin offered.

Defeated, Emma followed him to the car. But just as her friends were readjusting their bodies to seat her, they heard the gate creak. Someone had opened it. Emma hurried back. She could hear her heartbeat. Her tongue twitched in her mouth and she bit it softly. She didn’t want a confrontation with Mr. Dadzie. When she entered the yard, it was Mr. Dadzie’s second wife, Akos, who stood with a cloth tied around her chest and a big silver padlock in one hand.

“Good evening,” Emma said to her.

Akos nodded. “The old man is seriously angry,” she whispered. Akos was a couple of years younger than Emma. They had chatted a few times while fetching water from the large plastic tank in the backyard and on the days that Emma returned from work and found the woman sitting on a stool under the gnarled almond tree, holding her baby daughter. Emma had yet to understand why such a young woman was married to Mr. Dadzie and why she had agreed to be his second wife, a practice that even village women had begun to scoff at.

Emma rolled her eyes at the news. “Let him be angry,” she said to Akos when they separated, she to her apartment and the young wife into the house she shared with her husband and his first wife.

There was a loud and persistent knock on Emma’s door the next morning. She bolted upright, momentarily confused. It was six. She hurriedly tied a cloth over her diaphanous nightgown and answered the door. It was Mr. Dadzie.

“Good morning,” she said.

“Emma,” he sighed, his nose hairs flying at full mast.

“Yes, Mr. Dadzie.”

“Why have you chosen to bath in my drinking water?”

“Pardon?”

“I said why…you are disrespecting my house!”

“What have I done?”

“What have you done? You do not know what you have done? What kind of home are you coming from?”

Emma didn’t answer, even though she wanted to scream at him. Her hope was that if she stayed silent, he would stop talking and leave.

“What kind of girl comes home at that time of the night? What kind of girl?” he shouted, causing her to take one step back into her apartment. “Even monkeys live by rules. I told you the rules of my house before you moved in but you have chosen to flout them. I have tried to advice you like a father because I know that nobody is born wise in this world, but you have refused to listen to me. If you want to live like a loose woman, it will not be in my house. I will not allow you to disrespect me and expose my wives and children to this wayward lifestyle,” he said, wagging a knobby finger in her face so that she had to draw her head back. By then, his wives and children had gathered in the yard below and Emma’s neighbors, the teacher and her family, were standing in their doorway and watching the scene like it was a Ghanaian movie.

“I’m not a small girl,” she said, without meaning to. The words, which originated in her chest, had simply shot out of her mouth.

“Is that what you are telling me?”

“All I’m saying is that I’ve paid my rent and I take good care of your property. The time that I come home is nobody’s concern.”

“Saaa? It is not my concern that my gate is left open deep into the night to welcome armed robbers?”

“I came home at ten, not deep into the night. I understand the need for security but at the same time, you can’t put me under curfew. I never agreed to live like this.”

“Then leave! Pack your troubles and leave today, today, but I will not give you back a cedi of the rent you have paid; I am keeping all two years. A child who refuses to listen will feel pain,” he said with finality. He then turned and stomped down the stairs, his veiny hands gripping the cast-iron rail for balance. Emma shut her door, but not before she glimpsed the accusing look on the teacher’s face.

Inside, she sat on the edge of her pleather sofa. The man’s words were still ringing in her ears and the sting of the disrespect and humiliation that he had just heaped on her was getting sharper. Her hands were trembling. She breathed heavily and shook her head from side to side as if to negate his words. She picked up the phone to call her mother but then decided against it; her mother would show up and attempt to beat Mr. Dadzie up. That would only worsen the situation.

The man was being unreasonable in a way that she hadn’t anticipated when she began house-hunting. Her biggest fear then had been that she would end up with one of those landlords or landladies who, after demanding the upfront payment of two or three years’ rent, would increase the rent after a few months and throw tenants out if they refused to pay up. She had never imagined that she would end up with one who tried to control her movements and her love life. She found Mr. Dadzie’s expectations foreign, and bordering on the insane. If he had been a younger man she would have matched his madness with her own. There was no way that she could continue living in his house. She called Mensah and he agreed to meet her in a bar at the end of her street.

Mensah was seated and nursing a bottle of Guinness when she arrived. He wore a shirt that had “New York Yankees” emblazoned on its front and cubic zirconia studs glittered in his ears. She began narrating what had happened before she sat down.

“Stupid old man!” Mensah said with a ferocity that surprised but pleased Emma, after he had heard the story.

“I want to leave today,” she said, banging her hand on the table. The Guinness bottle wobbled and threatened to topple. Mensah steadied it.

“I understand, but I have to find someone to take your place. He’s not going to give you back your money, and two years’ rent is not money that you can allow to burn like that.”

“How long will it take to find someone?”

“It depends, knowing what I know, I have to find a married couple or some old person to come and stay there or that cantankerous man will chase the person out again.”

“I want to move out now. Can’t the police help me get my money back?”

“Police?” he snorted, “but you know how our police people are. They will not take your case seriously and will rather back the old fool. He just has to tell them that you’re bringing men into the house. As soon as they hear that, they will begin to call you ashawo and if you’re not lucky, your story will be on the front page of one of those garbage newspapers: PROSTITUTE FIGHTS WITH LANDLORD. You know how those reporters always hang around the police station looking for news. If you’re not careful they will spoil your name for nothing. Just try to cool your heart, I’ll find someone.”

Mensah’s words were reassuring; although only twenty-two, he was already a shrewd and reliable businessman.

That week, Emma made sure that she was always home by six. She checked in with Mensah several times a day in his cubicle where he oversaw the supermarket’s security. By Wednesday he had found an interested couple but they could only come to see the place on Sunday. She pressured him to look for others, in case this couple decided not to rent the apartment.

Thursday after work, she ran into Akos at the water tank. She was balancing her fat baby on her hip while she waited for her bucket to fill up. The water was only trickling in. Emma greeted her and set down her jerrican.

“The old man is not happy with you O,” she told Emma.

“I don’t understand him, what does he want?” Emma snapped. She then smiled apologetically; her confrontation with Mr. Dadzie had left her with a lot of anger that she needed to expel.

“He says that you don’t respect. That you should at least have introduced your boyfriend to him so that he could know who was coming into his house.”

“Heh? Is he my father that I have to introduce my boyfriend to him? And I don’t even have a boyfriend so…Or does he expect me to bring all my friends for his approval?”

“Akos!” Neither of them had heard Mr. Dadzie creep up. His scrawny chest was uncovered and carpeted with white coils of hair. He was breathing rapidly, causing his bird-like ribcage to contract and expand accordingly. His presence startled Akos so much that she almost dropped her baby. She supported the child with a second arm.

“What have I told you about talking to this girl? What have I told you? It is because of bad friends that the crab is headless,” he yelled at Akos.

Akos held her baby closer but said nothing. The baby began to fret. The water in her bucket began to overflow but she made no move to close the tap.

“If you want to run wild like this one here,” he said, pointing at Emma, “I will not hesitate to send you back to your mother.”

Akos nodded, her eyes trained on the sand beneath her feet.“Let me catch you again, just let me catch you,” he continued. He wagged a finger in her face and then for some reason, in the baby’s too. He then bent over and angrily twisted the tap shut and motioned for her to pick up the bucket. She dipped low to lift the metal handle, causing her grip on her baby to loosen. Emma wanted to reach out for the child but Mr. Dadzie stood resolutely between them. Akos began to walk away, struggling to balance the baby in one hand and carry the bucket in the other. Mr. Dadzie was watching her with his arms folded across his skinny chest. By the time Akos disappeared into the backdoor of their apartment, her hand had slipped from around the baby’s waist to under her armpits. The baby’s feet were dangling.

“You!” Mr. Dadzie turned to Emma. She ignored him and set her jerrican beneath the tap. The water began to dribble in. She was determined not to engage him. She remembered something that her father always said when her mother was gearing up to confront someone who had offended her: “If a mad man snatches your cloth from around your waist, you don’t follow him with your buttocks exposed to retrieve it.” What would she gain by exchanging words with this man?

He glared at her, expecting an answer. When he realized that she wasn’t going to say anything, he sauntered off. Emma exhaled.

The next day the banging on her door began at five. She was already awake and ironing her work clothes. Her hand froze at the sound and she didn’t move again until she began to smell burned fabric. She hastily lifted the iron and placed it aside. Should she even open the door to this man?

“Emma! Emma! I beg you, open the door!” It was Akos’ voice.

Emma sprinted to the living room. Her hands were unsteady as she unlocked and removed the iron bar that secured the door. As soon as she cracked it open, Akos rushed in, almost knocking her off her feet.

“Wha?” she began, but then stopped. Akos was only wearing a t-shirt and panties. While Emma was observing her, Akos locked the door and put the iron bar back in place. A few seconds later, the banging recommenced. Emma was confused.

“What’s happening?” she asked.

Akos, leaning against the door and breathing hard, didn’t respond.

“Open this door! Open this door!” It was Mr Dadzie.

“Please, don’t open the door,” Akos said. She stretched out her arms to keep Emma away. “What’s happening?” Emma asked again. She made no move to open the door.

The answer came from outside. “Whores. Shameless women. Dirty women. A married woman sleeping with another man,” Mr. Dadzie screamed, “I will kill you today.”

“Akos?” said Emma.

Akos was still not talking. Emma heard a sharp thump and then splintering. Mr. Dadzie was breaking down the door. Akos was jolted from her position against the hard slab of wawa.

Emma panicked. “Mr. Dadzie, please, I beg you, stop,” she said.

“I should stop? Are you asking me to stop?” he huffed. “Today you will learn that there is a consequence for every action. Let the person who sent you to find a man for my wife come and rescue you.”

“I? Found a man for your wife? Akos, what’s he talking about?”

Akos was seated on the sofa, her head bowed.

“You thought I would not find out. I heard them on the phone this morning. That worthless Mensah. That earring-wearing nincompoop. That good-for-nothing thug,” Mr. Dadzie railed.

“Is it true?” Emma asked Akos. This time she squeezed the woman’s shoulders so that she was forced to look up. Akos only nodded. Her bare thighs were covered with goose pimples. Mr. Dadzie had resumed hacking at the door.

“I didn’t know anything about it, I swear to God,” Emma yelled.

She didn’t know if he’d heard her above the thwack, thwack, thwack, of what had to be a cutlass against the door.

She had to do something. She ran to her bedroom window. There was little movement outside. One car drove by. And then she heard the porridge seller.

“Hot ricewater, hot ricewater,” the woman sang.

“Ricewater seller,” Emma called out, when the woman came into view, “please call some people, my landlord is trying to kill me.”

“Heh? Why?” the woman asked. She was looking straight ahead because she couldn’t look up at Emma without dislodging the huge pot that was balanced on her head.

“Please, just go,” Emma said, impatiently.

“Okay,” the woman said before she began speed-walking down the street as fast as her load would allow her.

Emma then picked up her phone and called Martin. She had wanted to call the police but couldn’t remember the ten digit number. She should have saved it when it was announced on GTV. She told Martin what was happening and asked him to call the police; they might come if she was lucky. Akos had followed her into the bedroom and was now locking that door. Emma stared at her but said nothing. Instead, she picked a cloth out of her wardrobe and handed it to the scared woman, who accepted but did not immediately tie it around her waist.

“It’s all because of my mother; I married him because of my mother. He takes care of her and my siblings,” she said, fingering the yellow squares that were patterned on the fabric. “I’m the eldest,” she added.

Emma nodded in understanding. This wasn’t the first time that she had heard such a story. She noticed that the apartment had suddenly become quiet. Mr. Dadzie had stopped trying to break down the door.

“Akos, come outside, I will not do anything to you,” he called out sweetly, too sweetly.

Neither Akos nor Emma budged.

“Are you coming?” he tried again.

“Harlots. Asanka. Show me your friend and I will tell you your character,” he bellowed, abandoning his ploy. He started hitting the door again.

On the street below, there were feet pounding the pavement and then fists pounding the gate. The porridge seller had brought the members of a local football team, who had been jogging. They began throwing stones at the locked gate and hollering for Mr. Dadzie to open it. Some of the young men began to scale the fence. The police’s siren was soon added to the cacophony.

“We’re safe,” Emma said when she heard the commotion outside. She fell onto the bed in relief.

“For now,” Akos said.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Lipochrome by Nathan Poole

Lipochrome by Nathan Poole

“…God will give you blood to drink.” –Sarah Good

It did not go away—as everyone said it would. At nine months Ida was diagnosed with an obscure disorder. It was thought to be caused by an infection in the eyes at birth, a condition that amplifies the production of the rare pigments in the iris, increasing them until they dominate the eye. When most babies’ eyes shift from the lapis slate of infancy to their final and common color, Ida’s eyes turned wolf yellow and remained that way. They smoldered under her white bonnet like filament at low voltage.

This was startling to everyone. To her parents. To those who cooed at babies and drew close to see her. To those who lifted her cap to peer in at the bland, lost little face, and found those inquisitive, lupine eyes.

Soon people lost their inhibitions completely. “Can I see?” they asked, waving and jogging toward her mother across the square that divided the cemetery from the church yard, following her into stores, down the produce aisle. Ida’s mother would often turn to find a strange man standing behind her, cornering her against the lettuce. No introductions. “Mind if I have a look?”

And what could she do? She would turn her child from her shoulder, bob her on her forearm and let the stranger’s eyes stare into Ida’s, “Ain’t that a thing,” some said. “They’ll go away,” said others.

What happened when Ida was fourteen was in many ways inevitable. She had been so long an object of curiosity—a kind of unconsummated desire—and the rumors had been in the wings from the beginning, jealous and impatient understudies, anxious for their turn on stage: “I bet she has a forked tongue,” “I bet she howls at night.”

In church that morning Ida had been holding her late grandmother’s wedding band in her mouth. She was bored and had taken it off her finger and was flipping it over and over on her tongue while the reverend, a soft-eyed older man named Quatrous, was preaching the prophet Amos.

After church her mother stayed and talked while Ida wandered outside to wait on the warm church steps. From there she saw a horse standing across the street in the shade of a tremendous live oak. It was tied by the bosal to an ornamental iron fence capped with sharp hand-hammered finials. The fence had been there for a hundred years and it lifted and sunk where the roots of the oak pressed up beneath it, causing sections of finials to aim inward in concave depressions and others to fan out lethally like the rays of the sun on old celestial maps.

She was moved toward the horse by a restless feeling the church service put inside her. Like the residue a flash bulb leaves hanging in the air—an exposure that turns with you when you turn and stays out in front of you when you close your eyes—the long stillness of the hour had made the world distant and unreal and the horse was a part of the dream. She wanted to touch the tight tendons of the leg, wanted to run her hand over the muscles and across the steep hill of the flank.

As her hand neared the horse’s front shoulder it seemed a spark left her finger tips, and if not a spark, something like it, something inside her, something she carried that leapt. An invisible surface was breached. The animal spooked and reared and she fell back and watched as the horse grew tall and then taller again, impossibly tall. It came down near her, the hooves clattering on stone. A taste of iron in her mouth, a notch in the tip of her tongue. The horse went up again and she watched as it tried to clear the old iron fence. She watched as the mecate caught and she watched still as the historic finials disappeared into the smooth barrel of its underbelly.

The sound it made was significant, married to its meaning. A song lived somewhere inside the sound and it drew men toward it. From the far end of the road, and from around the corner, and from across the street, they hustled toward the sound of the horse. But the noise Ida heard had not come from the horse but from somewhere inside her. The sound was the sound of her mind when she saw the horse descend, it was the sound of a sawmill clutch before the belt gains, the sound of resistance, of wishing it could all be turned back, the sound of a loud blister in her palm after a day of raking leaves, the long wooden pews creaking, the organ growl, the doxology, pedal tones that are felt before they can be heard. It was a sound like the nameless world.

The horse’s front hooves pawed and reached for the ground while the animal remained suspended. On the sidewalk, in the shadow, it seemed the horse was running hard in a four-beat gait and the shadow was something projected out of the horse, some vital extension escaping.

The mare bled out from its barrel. Its large eye widened above her. She watched the eye as the blood left the horse, black ink streaming down the scroll work, over the nodes and twisted pickets. The big eye rolled languidly and then centered itself like the by-point globe inside her father’s liquid compass, regaining its mysterious traction to the world. She watched the eye work to stay in the world, to keep a hold on it.

Men seemed to come from everywhere then. They mobbed around her, shouting to each other, crowding in. Their boot heels slipped in the blood, streaking it with clay. They scurried around the horse’s suspended body, over the fence, placing their backs alongside the animal’s body and lifting with their legs. This was all organized by shouting and by something unspoken, the frantic purposeful feeling, not unlike joy, that men take in things terrible and unlikely.

Shouts rose suddenly to stop lifting; a man who did not hear fell to the ground beneath the horse and when he rose his dark suit pants were purple with blood and brilliant in the sunlight. The mare squealed when the lifting stopped and stamped its back legs and the men around it moved away and the horse descended only farther into the finials until it stood with its front hooves on the ground. It rested. It contemplated its pain.

Everyone on that corner knew it was Quatrous’s horse and that he had just bought it the week before. He was one of the only men in Shell Bluff to still bring a horse into town and it was only on Sundays. Quatrous made the decision. He stepped out of the church across the street and without looking twice at the scene—the men sweating, their feet slipping in the blood—he asked one of the police officers for a pistol.

Ida had been carried across the street and propped up against the trunk of a large sweet gum tree. Her eyes were glazed and the world inside her pitched and turned. Her mother took off her shoes and threw them away and held her face and stared into it and saw nothing but the vivid gold eyes, focusing on nothing. The pistol snapped, ringing the air between the short buildings, and the horse sunk entirely into the finials as a large flock of pigeons rushed out from the limbs above Ida’s head.

The women in the prayer meetings shuddered to hear each new story—though they, most of all, spread them around—and would then commence to praying for Ida and her freedom from what they called her oppression. Many believed the incident to be associated somehow with her grandmother’s wedding band and wished her to take the band off.

Ida’s grandmother had lived with them for as long as Ida could remember and her presence in their house was robust, solid, heavy with laughter. Her grandmother seemed so physical an object, and by comparison her parents, who were not affectionate people, seemed frail, as if strong laughter would sift them right out of the world like ash.

Ida would sit with the old woman in the evenings for hours and run her fingers down the large distended blue veins in her hands, tracing them as they warped over the bones, pressing them down and watching them grow faint, disappear, and then appear again. Her grandmother never resisted being touched and Ida loved this about her. She would let Ida do her hair up in all sorts of bizarre arrangements, twists and bows with confectionary zeal, everything short of cutting it, and the grandmother sat with her eyes closed, drifting in and out of sleep.

Ida was twelve when her grandmother died and her grief was immense. The wedding band was left to her for her own wedding day, but she refused to leave it in its envelope in the stationary desk. She screamed when it was asked from her and the screaming rattled her mother’s nerves. She was allowed to wear the ring, with the condition that she was only allowed to wear it on her right hand. It fit loosely on her slim fingers and Ida developed the habit of keeping that hand pursed into a fist when she walked or ran, giving her appearance a new ferocity, as if she were perpetually charging up to sock someone in the mouth.

After the horse died a series of stories developed. Desire was let free. One of the first stories that circulated throughout Shell Bluff—and even beyond, into Milledgeville and Sparta—was one that a number of people attested to seeing personally. Her grandmother’s wedding band would disappear from Ida’s finger and reappear in her throat. It happened at school. The ring appeared suddenly in her throat and was trying to choke her. Ms. Addison slapped her firmly on the back and out fell her grandmother’s ring onto the floor.

“Why’d you swalla that?” the teacher asked.

“She didn’t though,” said another girl. “It disappeared right off her finger. I saw the whole thing. It was there and then it was in her throat and she was choking. It showed up in her throat. I saw it all. I saw the lump in her throat. It’s trying to kill her.”

The word “booger” and the song, “Ida and her booger sitting in a tree…,” became a musical phrase that lived in Ida’s landscape, a bob-white’s call, a whippoorwill. The sounds of the words and the notes of the song were factual things that traveled through the air and scared her. She was oppressed. She was prayed for. All of it scared her.

Soon Ida hated being left alone, certain now, after all the words, and songs, and taunting, and prayers, that when she was alone she was not. Her fear of being alone, the fear itself, fed the rumors and as the rumors grew so did her reluctance to be around too many people, or too few, or to come near an animal, any animal, which could be difficult when almost everyone in Shell Bluff owned some number of livestock.

There were other things to reignite the story whenever it seemed to be dying down: a girl said she had a secret to tell. Her name was McCuen. She had six brothers all called by the same last name and no one knew their first names. They were McCuens. To call one was to call them all, but for Ida, McCuen was the girl who reeked of kerosene during the short Georgia winters. She was the girl who lived with her tribe of brothers and was skinned-kneed and ugly in appearance despite the fine features of her face and the way her eyelids lay softy over her almond shaped eyes, as if they were perpetually half-closed.

McCuen led Ida by the hand into the bathroom stall and instead of disclosing a secret began to softly stroke her arms, and then her cheeks, and hair. Ida felt the pressure of the girl’s hand on her head and then the hand moved to her cheek and then to her shoulder and Ida’s heart began to pound and at the same time she struggled to keep her eyes open, as if she were running full speed into sleep.

After the first kiss Ida let her lips part and McCuen kissed her again and it summed in her mind into a litany. It was a hot afternoon on a bank of red maples turning suddenly cool; it was water dripping off her fingertips, tugging each finger toward the ground with invisible force; her hand was swollen from a wasp sting, a hand that was numb and large and didn’t feel like her own when she touched it with the other; it was six pieces of coal she once found in her school desk, black like sin; it was soft like owl feathers and heavy like fruit.

They might have kissed a thousand times—it seemed an infinite space between each one. She never kissed back but it did not matter, she did not have to. They came one after the other. There was another girl there who saw them standing together, who had walked in quietly behind them and saw their shoes staggered in, facing each other. And she could tell, she just could, by the position of their feet and the odd silence, and she knew what was happening. It was this girl, hurt with longing and self-consciousness, who told her mother what she had not seen but knew, who told her friends that she had seen what she had not, who told everyone she could that Ida had seduced McCuen with her witch eyes. Then she added to the story as it needed adding, added that she heard them speaking together, in one voice speaking, and that they spoke in a language she had never heard before.

Ida’s parents received visitors who offered their advice, who spoke of how they had cured their own children from similar dispositions. McCuen spent two weeks out of school and no one knows what happened to her those two weeks, but when she returned to school she never looked at Ida again.

A few months passed and Ida was exhausted and numb to everything. She avoided animals completely, certain that whatever was with her would scare them, cause them to jump off of cliffs or hurl themselves on sharp objects.

Ida would be made a member of the church in early August. She completed her membership class uneventfully and the date was printed in the church bulletin with the names of the other children to be made members. The following week Ida’s named stood alone and the other baptisms were all rescheduled.

On the afternoon of the event Ida was picked up along with her family by a tall young man with greasy hair who drove a long pink Buick convertible. He introduced himself as Jimmy. Jimmy had just come down from Columbia with his new wife and was excited to be part of the occasion. On hearing from his brother-in-law that there would be a baptism he insisted on driving the family. He treated them like prominent figures in a grand parade. He left the top down on the Buick. He spoke loudly, over the radio—which he did not turn down, even as he pulled into the church parking lot to meet the caravan that contained the minister and what seemed a large number of cars and trucks that would follow them to the river. Compared to her father’s truck, the Buick went smoothly, suggesting the familiar road with its washed out creeks and roots while transcending it. Soon the other cars in their party were no longer visible. Ida gave up tucking her hair behind her ears and let it swirl around her face while her mother kept both her hands on her hat and her father wore his dark suit and a tight smile across his embarrassed face.

“I remember my first baptism,” Jimmy yelled at his passengers. “I thought the man wouldn’t ever let me up and when I did get up I tried to sock him in the face. He was messing with me. I swore he was. He looked small to me and I thought I could take him but he was strong as an ox. God. He was strong. He threw me right down again into the water and held me there until I gave up.” He reached back and slapped Ida on the leg and laughed as the Buick veered slowly toward the tree line. He corrected into the road and aimed the rearview mirror at her. “So don’t try it,” he winked.

“I thought you said you didn’t baptize till you married Q’s little sister.” Ida yelled back.

“Honey, that’s not your place,” her father turned.

“I didn’t.” Jimmy said.

“But you were baptized as a little boy?” she asked.

“Honey,” her father said again.

“That’s true,” he declared, laughing, “I got baptized as a boy but didn’t get saved till I married Q’s sister. I guess I was on layaway.”

Jimmy’s laughter caused the limbs to shake overhead and the light to spill down through the trees. He had tears in his eyes he was laughing so hard and the car was swerving and Ida felt herself being made new. Thurston Harris’s Litty Bitty was playing on the radio and the music was infecting them all. A strange sense of buoyancy entered her bones. She would walk across the water, she would bob like a cork. They smiled as they looked at each other, a family but strangers to themselves, figures made from air and sugar and gossamer, confections from a dream.

Baptisms were carried out in an eddy along the Savannah River where it takes Miller’s Pond Creek. There is a sandy wash a few steps up the creek mouth with good shallow clear water and the current is soft. Quatrous often said he loved the spot. It reminded him of those lesser-known lines from Cloverdale: “Lead me forth beside the waters of comfort.” “You see, the water doesn’t need to be still,” he would say on a Sunday morning, “‘Cause the best water keeps on moving, don’t it. You go get a drink from Telfair pond up above the dam and tell me it don’t taste like a slick froggy. Now go get you a drink from Keysville at the head and you’ll lay yourself face down and say Lord have mercy. Good water knows it’s not done. It’s got a race to run along the earth. Amen? It’s not home. No. But it’s bringing home with it, just not there yet. Who else ain’t home? We aren’t. That’s right.”

As the cars pulled up they could already see it wouldn’t do. The river was swollen and banking violently. The party walked the upstream path together in a single file just to see how the creek mouth looked and it didn’t look any better. What had once been an eddy was a brown churning place. Every so often a log would drift in and spin a few times like it was in a washer and then shoot back out into the river.

The men stood on the bank watching the river surge by, already intoxicated by the level sheen of light—if only it were small enough for them to run their hand across it, like a table top, to examine it, they would. Quatrous took off his shoes and rolled up his pant legs and prepared to wade in a few feet where it seemed the slowest. He needed to see how bad it actually was before he would give up his spot.

“Easy now,” Jimmy said, laughing.

“Woooo,” Quatrous said to the crowd, widening his eyes. They laughed.

“Is it cold enough?” Jimmy yelled.

“Woooo,” he said again, “no, it’s tugging though. It’s tugging.”

He waded back carefully and reached his hand up to Jimmy to help him step out just as he slipped in the slick kaolin clay that banded the bank. He went down on his face before he could get his hand down and the current pulled him immediately out of the creek mouth. As it did he rolled casually onto his back as if he were expecting as much to happen. It seemed like his belly was made of cork the way he shot out into the Savannah, bobbing in the rapids as he accelerated. He was cruising very quickly out of sight, disappearing in the shade of large maples and hickories and then reappearing on the other side moving faster than he was before and then he was gone.

Ida and Jimmy were racing along the bank shouting with others, Jimmy running ahead and laughing so hard he could barely keep Quatrous in sight. Ida’s feet slapped along the packed footpath. She caught glimpses of Quatrous, down low close to the bank. He would occasionally roll onto his stomach and reach for a branch overhead and then, having missed it, roll back onto his back to look where he was heading. When there wasn’t a limb to reach for he kept his arms down by his side and used them as paddles to direct himself.

After two or three attempts he finally got hold of a low hanging Possumhaw limb and was immediately stretched out longways downstream so that he couldn’t get his feet underneath him to walk out for fear of increasing the drag and breaking the branch. They all moved to go down when Jimmy grabbed Ida by the arm and said, “No sugar, you stand right here.” He made her hold onto a skinny tree and nodded to confirm that she would not leave it. He and another man went down the steep bank carefully together holding onto washed out tupelo roots.

“You finished bathing?” he yelled down to Quatrous.

“I’m just thinking,” Quatrous said.

“About how to get out?”

“No. About what it means.”

“It means you’re a clumsy old man, is what it means.”

“Maybe. Maybe,” he said, the water streaming around his face, framing his red skin. His thin white hair pasted and pulsing on his brow like a jelly fish.

“Do you want to hear my plan?” Jimmy said.

“Go ahead then.”

“I’m gonna hold onto this tree with one hand and put the other on your arm and when you stand up the current is going to swing us around and pull you into bank and then you can grab onto those roots over there. How’s that sound?”

“Sounds like a plan.”

The rest of the party arrived as Quatrous was crawling carefully up the bank on his hands and knees and Jimmy was making his way up alongside, holding onto the trunks of trees, practically climbing from one to another. Ida’s father held Quatrous under the arm as he stood. The preacher took off his tie and rang it out. “Well, where to?” he said. “We might as well do this while I’m still wet.”

Ida was baptized in a pond off Claxton-Lively road. It was fed by an aquifer and it was the coldest water she could ever remember being in. He put her under and the water ran across her chest and she thought she felt her heart stop. When he pulled her back up she was shivering so hard she couldn’t walk. Quatrous lifted her and carried her out of the pond and she sat down in the hot sand beside it while waves of dizziness, something near ecstasy, shot through her mind and body. The sun warmed her and she thought of nothing and it was in the nothing that the figures and voices of her life swung around her like a globe of stars being cranked and she heard the sound of the Buick’s radio and she felt the heavy light entering her again, an opening in her mind, the opening of a fist.

It had been a little over a year since the horse had died and Quatrous thought it was time to bring her near an animal again. He thought they might give it a few tries, thought he would even teach her to ride and that the sight of her up on a horse would be good for the neighbors to see.

The Latvian was a heavier animal, good for light draft work and riding and above all, calm as a tortoise. Ada was already standing when she saw Quatrous walking the animal around the bend in the road. Her dress was clinched in a ball in one fist above her knee, her other hand on the door knob. Her eyes were wide and tracked the horse fiercely as they came. She stood like a deer at the edge of heavy woods, every nerve balanced. As soon as Quatrous turned up their long drive and it became clear he meant to visit the house she ducked inside.

He knocked on the door.

“Ida, come out here and meet this lady, she’s real sweet.”

He waited. He heard Ida and her mother talking softly.

“You want to know her name? Abigail. That’s sweet, isn’t?”

“Go on,” her mother said.

Quatrous left the door and went down to the animal and petted it and pulled an apple from his pocket and feed it a bite and pulled the apple back.

“Want to feed her this apple?” he called.

Ida came out with an uncertain look on her face and took the apple carefully, keeping her eyes on the horse like it was a blasting cap.

“Go on,” Quatrous said. He motioned with his hand to show her how to lift the apple up. She watched the motion from the corner of her eye and lifted her hand up.

The horse took a step forward, moving her mouth out toward the apple. Ida pulled the apple back quickly and then launched it across the yard into the garden. The horse turned to watch the apple fly and when it turned back to her she caught it on the side of its nose with her closed fist. The Latvian’s eyes grew wide. She slapped it several more times with her palm as it turned from her in a trot. She screamed and caught it once more on the flank with the flat of her hand, sending it into a steady gait out of the yard toward the road. A truck coming down the lane slammed on its brakes to let it pass in front. The horse swerved tight around the truck’s hood, almost colliding with the fender before heading off in the opposite direction along the creek bed. It looked as if it would run the rest of the way home if home wasn’t in the opposite direction. The mother screamed after her daughter but Ida did not stop. She disappeared after the horse, the newly long legs pawing the ground with incredible speed. “I’ll grab the truck,” her mother said. She went quickly inside the house. The screen door slammed.

Quatrous walked calmly out of the yard with his hands stuffed down in his pockets. His head down.

“Damn it,” he said to himself.

As he came to the road he saw the hoofprints where they turned up the packed earth and he saw the ring lying brightly beside the spot in a slick of mud. He put his boot heel on top of it and pressed it down deep as if it were the head of snake. He kicked some earth over the spot to trod it down a second time and waited there for Ida’s mother.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Singing Backup by Jason Kapcala

|

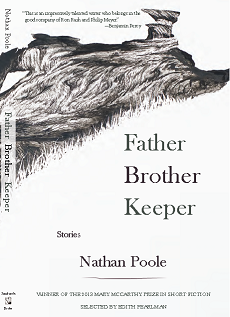

“ Father Brother Keeper is marvelous. To read the work of Nathan Poole is to discover an immense, beautiful secret, rich with private histories and the rhythms of our complex, haunted world. These are stories to cherish, a debut to celebrate.” ~ Paul Yoon Available February 15 from Sarabande Books |

TWO POEMS by Patrick Rosal

TEN YEARS AFTER MY MOM DIES I DANCE

The second time I learned

I could take the pain

my six-year-old niece

—with five cavities

humming in her teeth—

led me by the finger

to the foyer and told her dad

to turn up the Pretenders

—Tattooed Love Boys—

so she could shimmy with me

to the same jam

eleven times in a row

in her princess pajamas.

When she’s old enough,

I’ll tell her how

I bargained once with God

because all I knew of grief

was to lean deep

into the gas pedal

to speed down a side road

not a quarter-mile long

after scouring my gut

and fogging my retinas

with half a bottle of cheap scotch.

To those dumb enough

to take the odds against

time, the infinite always says

You lose. If you’re lucky,

time grants you a second chance,

as I was lucky

when I got to hold

the hand of my mother,

how I got to kiss that hand

before I sprawled out

on the tiles of the hallway

in the North Ward

so that the nurses

had to step over me

while I wept. Then again,

I have lived long enough

to turn on all the lights

in someone else’s kitchen

and move my hips in lovers’ time

to the same shameless

Amen sung throughout

the church our bodies

build in sway. And then

there were times all I could do

was point to the facts:

for one, we move

through the universe

at six hundred seventy

million miles per hour

even when we are lying

absolutely still.

Oh magic, I’ve got a broken

guitar and I’m a sucker

for ruin and every night

there’s a barback

who wants to go home

early to bachata

with his favorite girl.

I can’t blame him or the children

who use spoons for drums.

And by the way, that was me

at the Metropolitan stop

on the G. I was the one

who let loose half my anguish

with an old school toprock

despite the fifty-some

strangers all around me

on the platform

waiting for the train

about to trudge again

through the city’s winter

muck. Sure, I set it off

in my zipped up three-quarter

coat when that big girl

opened the thunder in her lungs

and let out her badass

banjo version of the Jackson Five,

all of which is to say, thank you

for making me the saddest man

on a planet teeming with sadness.

The night, for example,

I twirled a mostly deaf woman

in a late-night lounge

on the Lower East Side

and listened to her whisper

a melody she was making up

to a rhythm she told me

she could feel through her chest,

how we held each other there

on a crowded floor

until the lights came up

as if we were never dancing

to the same sorrows

or even singing

a different song.

UPTOWN ODE THAT ENDS ON AN ODE TO THE MACHETE

What happens when me and Willie

run into each other on a Wednesday night

in Brooklyn? He asks, “Where we going?”

And that’s not really a question.

That’s an ancestral imperative: to hail

any yellow or gypsy that’ll stop on Franklin

and Lincoln to fly us over the bridge then

zip up the East Side where the walls

are knocking to Esther Williams or Lavoe.

And you know Willie daps up Orlando

and I say What’s good! and it don’t take

three minutes for me and Will to jump

on the dance floor or post up at the bar

sipping on Barrilito or to tap on my glass

a corny cáscara with a butterknife

like I’m Tito Puente but I have no clue

I really sound like a ’78 Gremlin

dragging its tailpipe the length of 119th,

which is to say, it don’t take long

for Willie and me to be all in. And that’s when

out of nowhere in the middle of the room’s boom-

braddah macumba candombe bámbula

this Puerto Rican leans over and says to me

real slow, “Everybody is trying to get

home.” And I’m like, “Aw fuck.” because

I’m on 1st Ave between 115th and 116th

not even invested in the full swerve yet.

It’s not even five past midnight and Will

is dropping science like that. Allow me

to translate: There are neighborhoods in America

where a man says one simple sentence

and out flow the first seventeen discrete meanings

of home. If you haven’t been broken by the ocean,

if your own weeping doesn’t split you down

into equal weathers: monsoon, say, and gossip,

if you can’t stand at the front door

of an ancestral house and see a black saint

staring down at you, no name, no judgment,

if you haven’t listened to the town drunks

laughing underneath a tree they planted

so they wouldn’t forget your pain, then your story

must have a whole other set of secrets.

You must know what it’s like to expect

an invitation. You might not know what it’s like

to wonder if someone is even waiting

for you to return. Your idea of home

might not contain ways to call blood cousins

from another time zone or just shout

from the middle of the road. There are those of us

descended from peasants who never had to travel

too far to visit the smiths who craft knives

from hilt to tip, who cook blades

that split the wood or carve the rind

from flesh. I once went to visit the men

who make the machetes of the Philippines.

There was a time, I didn’t care where

those knives came from, how the men and women

stoked the embers and dropped their mallets

with a millimeter’s precision. When I was young,

I thought hard was the mad-dog you could send

across a crowded bar. I thought hard

was how deep you roll or how nasty the steel

you bring. In some neighborhoods of America,

hard is turning down the fire just enough,

so you could kiss the knife and make it ring.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Reprise by Kathleen Hellen

Singing Backup by Jason Kapcala

“Drinks,” Muzzie says. “You, me, and Chen—a celebration in Dizzy’s memory. Not a drinking party.” He won’t go that far with it—but Kev knows that though he never went to college, never set foot in a frat house, Muzzie holds a pretty clear definition of what a drinking party entails: keg stands and beer pong and at least twenty women. Though it’s his first night back in Pennsylvania after almost ten years, he knows every note Muzzie’s going to play before he ever plays them. That’s the way it is among former band mates.

The drinking will take place at The Smiling Skull, a bar outside Emberland, and the way Kev sees it, he’s got no choice but to go. Muzzie, in full bandleader mode, has let slip the dogs of guilt and gossip. He’s requested the honor of Kev’s presence, called him up to the big show for the kind of drinking they never got to do back in high school, at least not legally, and word’s gotten around: The Mourning Afters are back together—one night only—and even if they won’t be performing, you can still stop by and throw a few back with their long-lost frontman, Kev Cassady.

Kev, to his credit, at least looks the part of a rock star. His T-shirt, Aerosmith today, is authentically faded. His normal flannel traded in for a mustard brown cardigan, in honor of Kurt Cobain on the anniversary of his death, though he’ll be disappointed later when no one in the bar picks up on it. There’d been a contest back at Tony’s, the not-quite-Los-Angeles-but-you-can-smell-it-from-here dive bar he’d hung around in with the rest of Del Lago’s fading rockers, one that went something like this, Name the greatest dead musician after Cobain? Free drinks for the guy with the best answer. Shannon Hoon a popular choice. Layne Staley another. But Kev was always partial to Andrew Wood. Without Wood, you wouldn’t have had Temple of the Dog or Pearl Jam, and Alice in Chains never breaks through to the big time. He never won any free rounds with that answer—Wood died four years before Cobain—but he kept tossing it out there anyway. Wood was a rocker worth buying a round for.

Dizzy, too—though Kev’s not so sure it’s a great idea.

In Emberland, The Smiling Skull looms like a set piece from an action flick about anarchist biker gangs that roam Death Valley picking off unsuspecting tourists. You’ve seen the movie about a hundred times: Some nervous-looking rebel hoping to earn his stripes picks a fight with the wrong dude, a loner-type with an eye patch, a guy who’s just minding his own business, drinking to forget his badass past. The young squid, hopped up on whisky and bath salts, ambushes Eye Patch in the parking lot and leaves him for dead, maybe kills his pretty barmaid girlfriend by accident—the one who’s never seen the ocean—and before you know it, there’s a ruthless one-man war party roaring down the highway in hot pursuit of the whole gang.

That’s the real charm of the Smiling Skull.

Otherwise, it’s pretty much like any other small-town bar, serving cold beer in the bottle and watered down drinks from the well. Muzzie’s snagged a table near the back, surrounded himself with drinking buddies—guys Kev recognizes from high school, the girls on their arms closer to their teens than their thirties. It’s a real “Glory Days” crowd, in the Springsteen-ian sense, and tonight they all want to hear about Kev’s exploits in The Golden State. He’s the boss, has got top billing, and they’ve gathered so that he can serenade them with tales of what it means to be a flesh and blood rocker. Not that they believe him to be anyone important. They’re all smart enough to know he isn’t rich or famous, but they remember The Mourning Afters, and they want to know when his album will be made available on iTunes. They’ve heard that on the West Coast a man with a guitar and a demo tape and a notebook full of big ideas can make a cottage industry of himself. After all, isn’t that how all the great bands did it going all the way back to the Beatles? They’re hoping that maybe he’s brushed shoulders with someone they’ve heard of—Eddie Van Halen or Ritchie Sambora.

It’s a different world today, nothing like the 60s, or 80s, or even the 90s for that matter, but they don’t want to hear about that. They want the classics. They’re chanting for Kev to play “Freebird” for the hundred-twenty-seventh time. And what choice does he have? You always give the fans what they want.

It should be an easy-enough gig. These are men who buy their polo shirts in bulk. They lease sensible cars. They’re hardware store clerks, high school teachers, IT professionals. Most have never left home, except maybe during college where they sowed their wild oats enthusiastically and returned five or six years later with news that the world is, in fact, much larger than Emberland and rounder than previously reported. Their girlfriends wear heavy concealer over their pimples and dayglo flip-flops on their feet. It’s the kind of group that hangs out in a bar with a steer skull on the sign. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out the script. And yet, when conversation turns to California, Kev disappoints. Offers up a shrug. Talks weather and traffic.

“The Chinese food is top notch,” he says.

Eventually, banter swings back to the local—whether it’s going to be a dry summer again, whether any of the men will find time to get out in the streams before Memorial Day, whether the high school baseball team will fare well at regionals—and Kev takes the opportunity to ask Muzzie, “What happened to just you, me, and Chen?”

“I’m here,” Muzzie says. “Chen’s on his way. The question is: where the hell are you?”

Kev shrugs. I’m here. Just wondering.

The beer—Muzzie has been ordering an endless round of pitchers for the table—is watered down. The appetizers stingy. A plate of nachos, brand-X tortilla chips with a toxic yellow cheese sauce and pickled jalapeno slices from a can. Soggy onion rings, grease pooling on wax paper. You can’t expect too much, they tell him. On the weekend everything has to last to closing time. Including the entertainment. Through a beer fog, Kev hears Muzzie say, “Ask the man of the hour. He’ll tell you all about it.” He’s talking to a guy with a big gold cross chained around his neck—worn on the outside of his shirt, of course. The man’s girlfriend is a good head taller than he is. She’s turned in her chair, holding her shoes by their straps and furiously chatting with one of the other girls.

“Muzzie tells me it’s a rough life being a musician. I guess you probably play a lot of joints like this one to make ends meet.”

Rock and/or Roll. Rock—with or without the Roll. Rock, and could you please bring the Roll on the side? The topic of the hour. Kev can’t think of anything he’d rather talk about less.

“You don’t know the half of it, bro,” Muzzie says. “My man’s eating his food out of tin cans six days a week, and on the seventh it’s eat the can or go hungry.”

Muzz, Kev thinks. Give it a rest. He finishes another pint.

“That’s the high cost of free living,” Muzzie says. “Everybody thinks your average rocker is just a showman, but you’ve got to be equal parts musician and accountant, even the lowliest of the low. Out there,” he says, pointing in the general direction of the door. “Even the littlest worms ride big hooks.” He elbows Kev. You’re on.

Kev’s never been a mean drunk—a little melancholy maybe, his perception heightened by the alcohol rather than dulled—still he could hack Muzzie apart with an axe right now. Even at sixteen, booze had strange effects on him, made him see things he didn’t want to see, and so he’d sworn off it for the most part. Drank ice-water more often than not. Nursed a beer when the occasion called for it. But tonight’s different. He’s home—back sitting among people he never expected to see again—and in a funeral parlor across town, Dizzy’s body is lying motionless in a pine box, his second-hand Fender slung across his chest, perpetually silent. Floating above the table, Kev watches himself pour another, sees Muzzie singing his lonely ballad though the volume has been turned way down. At the bar, the bartenders, weekend replacements, rush in slow-motion to refill drinks. They’re yin and yang—one a cage fighter with a twisted nose and a nasty looking cheek scar, the other the sensitive type, a mustard stain on his collar but no worries, his mom uses Tide with bleach. Muzzie jabs him again, harder this time, and Kev takes a long sip. Stalls for a while.

“Chit-chat. Swap lies. Baffle them with your glorious bullshit,” Muzzie says. “Is that too much to ask of an old friend?” He’s followed Kev to the men’s room, forgotten the unspoken rule about not talking to a guy when he’s holding his dick.

“Right now, this is a delicate enough operation without you crooning in my ear,” Kev says, focusing his aim on the pink urinal cake in front of him.

“In case you’ve forgotten, small talk is a currency in this town. Thanks to small talk, I drink for free most nights. And Kev, buddy, I love drinking for free. I love it, man.”

“God forbid I ruin your discount, Muzz. It’s not as if I have a lot on my mind right now,” Kev says, zipping up, and when he gets to the sink, Muzzie’s waiting with a paper towel in hand.

“Just be human,” he says. “That’s all I’m asking.”

Kev nods, though mostly because that’s the direction his chin is moving anyway. Muzzie’s talk of talk and currency makes his head swim. His brain buzzes like a blown-out amplifier. In truth, there’s little about his time in California that he wants to share, least of all with an expectant crowd. Least of all with Muzzie. He’s let them think he’s something he isn’t, and now he’s in no condition to maintain the ruse, to give it the TLC it demands. The real story—that he squandered time in a bar with other wannabe musicians while his guitar case gathered dust, that he waited a lot of tables and watched a lot of basic cable, that he lasted all of three gigs as the front man of a Pearl Jam cover band, The Jeremy’s, before his band mates took a secret vote of no-confidence and started auditioning replacements behind his back—is an unforgiveable sin. Better he should’ve rotted away in small-town obscurity.

Give them what they want, he thinks, splashing himself with water, shaking out the nervous energy, pumping himself up the way he would have had he ever gotten a chance to take the stage in front of a real monster crowd, but the truth is he’d rather be anywhere else right now.

“I figured you’d want all this,” Muzzie says, leaning on the door. “All that prodigal son stuff.”

“Sure,” Kev says. “Let the record show you’ve got a big heart.”

Exiting the bathroom, the bar looks even more crowded than Kev remembered. It’s doubled in volume in the time it took to drain one eighteen-ounce bladder. Young people standing shoulder to shoulder, jostling.

“No one ever fell over dead from telling a story, you know?” Muzzie says, clapping him on the shoulder, and then, somehow, as if by magic, he’s disappeared into the crowd.

Right, Kev thinks. You get their attention, and I’ll break their hearts.

At the end of the bar, one of the girlfriends is sitting by herself, a spot open next to her, her boyfriend with the big crucifix nowhere to be found. “So you’re the one who got out,” she says to Kev who, picking his way through the throng of bodies, does a double take. He notices her out of the corner of his eye, the one who’d been holding her shoes, an unlit cigarette dangling from her lips. And for a moment, he wishes he was the kind of guy who carried a lighter. Muzzie is nowhere to be found, has undoubtedly made his way back to the table to gather the groupies for round two. The girlfriend’s purse sits in her lap like a pet. It’s one of those impressively tiny bags that snaps at the top. She’s dressed in tight blue jeans and a teal shirt that shows off her tan cleavage. Her hair piled high on her head, intentionally messy.

“Who are you supposed to be?” she asks, eying his sweater. “Charlie Brown?”

“No one special,” Kev says, pointing down at the empty glass with lipstick marks. “Can I buy you another round?”

“I’m not really drinking,” she says. “I’m waiting for the bathroom.” And they both glance back at the restroom hallway, as though to catch the faint sound of flushing toilets.

“I’d offer you a light,” Kev says, his shrug conveying the rest.

“I’m not really smoking either,” she says.

She picks the straw from her glass and noodles it in her mouth, and in that moment she seems older than he’d first guessed. She should be somewhere else—sitting with her girlfriends from work at the tiny Chili’s bar just off the highway or maybe changing into a pair of flannel PJs and curling up on the sofa with a glass of Chardonnay and a bag of microwave kettle corn. This ain’t her scene.

Kev says, “Your boyfriend was grilling me pretty hard about music.”

“That’s a terrible come on,” the girl says. “If you keep saying things like that, no one is ever going to buy that you’re a rock star.”

“I’m not a rock star,” Kev says. “And that wasn’t a come on.”

“Try saying it again, only put the emphasis on ‘star’ this time. I’m not a rock star,” the girl says, pressing her finger to her chin.

“I’m not a rock star,” Kev says.

“Star,” she says. “Rock star. You keep practicing. I’m sure you’ll get it eventually. Before you know it, they’ll be throwing their panties on stage.”

“Who are we talking about here?”

“Muzzie,” she says. “And the rest of those idiots.”

Kev glances back toward the table. They are idiots, he thinks. But so’s he. In fact, he’s made a living out of being idiotic. Wasn’t that the joke about the difference between a livelihood and living—one makes you money, the other makes you poor? Eight years ago, The Mourning Afters had all had dreams, but he was the only one dumb enough to actually believe that following his was a good idea. At least, that’s part of the story. Kev thinks about telling her this, starts in with a clever reply, but when he turns back, it’s only to see the girl disappearing into the men’s room.

Back at the table, Kev’s arrived just in time to watch two of the boyfriends start arm-wrestling. They’ve stacked the dirty plates like a tower, swept away the crumbs and the congealed gobs of cheese sauce. Rolled up their shirtsleeves, their arms stretched across the tabletop like long, white fish. The two men look at the others, grin. They’re playing, but not really. It’s what happens when you stick around the same town too long, Kev thinks. The concept of play becomes all twisted up in your mind. It gets lost among the primitive high school desires that somehow never go away. So you laugh, and you make jokes about it, trash-talk like a couple of testosterone-crazed jocks, until the arm-wrestling goes on just a little too long or one of you tries a little too hard—perhaps a vein pops out at the temple and threatens to give you both away. You’re about three seconds from everyone else realizing the sad truth: that somewhere under all the congenial bullshitting, the two of you really care who wins this pissing match. And then what choice do the two of you have? Inevitably, someone has to take a fall. The winner gets to gloat.

Kev hears the crowd groan, looks up from his beer in time to see the taller of the two guys kiss the air around his biceps.

“Have we really run out of things to talk about?” The voice floats from just over Kev’s shoulder, and he half turns so as not to miss the spectacle surrounding Conor’s arrival. Conor, the once-and-never-again bass player for The MA’s. Conor who’d had more than a little to do with Kev’s decision to leave town. He pulls up a chair at the far end of the table, next to Muzzie, parts his sports coat and straddles it backwards and, after he’s shaken the right hands, bumped a few fists, winked at a couple of the girlfriends, he nods at the waitress, and from the bar she escorts his first magnanimous purchase of the night: a round of shots for the entire table.

Muzzie scowls—he’s wearing the look of the usurped. The shake of his head says, This is your fault, Kev Cassady. You bombed. Cut short the set list and left a gaping hole. And look what happened.

Kev shrugs. Sorry, Muzz. Maybe if I could see the set list in advance from now on?

He’s actually relieved to be out of the spotlight. Let Conor carry that burden with his unbuttoned collar and his gold watch and his perfectly trimmed fingernails. Kev’s more concerned about Ramie—she’s nowhere to be seen, and that’s a good sign. It might mean she isn’t here at all. Though maybe she never comes here. Truth is, he doesn’t even know if Ramie and Conor are still an item. Muzzie would know, but Kev won’t be asking that question any time soon. Got too much sand in his pee-hole, as his Dizzy would say.

“To Dizzy,” Conor says, as if on cue, raising his glass. The rest of the table follows suit. “They say every man has his demons. That was definitely true of our dear departed friend. But if I know Dizz, he’s up there somewhere strumming on the prettiest Strat you’ve ever seen, and he’s looking down on all of us right now, happy to see so many of his pals gathered here celebrating life.”

There’s a million and a half wrongs in that stupid salute. For starters, Dizzy wasn’t the kind of guy to play a shiny Stratocaster, or any other “pretty” guitar. He’d have sneered at the idea. Second, Dizzy didn’t know or couldn’t stand half the people at this table. If he were here now, he’d be in the bathroom, hiding from the crowd and shooting up. Dizzy wasn’t possessed by any demons. He wasn’t haunted by bad memories or dark thoughts. He just loved heroin. A lot, as it turned out. The only question that remains, as far as Kev is concerned, is whether or not it’s tasteless to raise a glass to his memory.

Still, Conor’s address is met with a chorus of applause, the requisite encores, and from across the table, Kev watches as Muzzie shuts his eyes and leans far back in his chair.

“So, you seen Ramie, yet?”

It’s an obnoxious question—the kind that only gets asked when you’re closing down the bar, drunk and bored and maybe looking to pick a fight. Muzzie’s band of merry drinkers is down to four: him, Kev, Conor, and the guy with the cross whose name Kev can’t remember now. They’re drinking a double-shot of something Conor calls “The Three Wise Men”—Jack, Johnny, and Jim—and Kev keeps pinching his legs beneath the table to make sure they’re still attached. He shakes his head at the thought of Ramie, imagines her shaking her Joan Jett-haircut right back at him and twirling her drum sticks over her head.

“You should look her up,” Conor says, leaning conspiratorially across the sticky wooden table.

“Now why would I want to do something like that?” Kev says, leaning back and studying the steer skull behind the bar. It seems to be following his gaze. Maybe even mocking him a little—Hey, pard, settle down now; no need to go seein’ red. Kev shakes the thought away, and it must signal some sort of weakness to Conor because he sinks his teeth in deep and doesn’t let go.

“Seriously. You should,” he says.

“Last I heard, you two were a couple now,” Kev says.

Conor rolls his rocks glass in his hand as though he’s trying to warm it up and grins down at the ice. From the wall, the steer skull chimes in without invitation: Listen to that feller, buckaroo. If you were as horny as I am, you’d mosey on down the road and give that filly the ole’ what-for.

When Conor finally whips his head up, his eyes practically gleam. They’re beautiful eyes, Kev thinks, terrifying. They remind him of the first time he ever watched Pearl Jam’s Jeremy video, the way Eddie Vedder with his high cheek bones and intense grin made him feel terrified and maybe a little confused. “Oh, I wouldn’t say that exactly. We’ve scratched each other’s itches from time to time.”

“Sounds sexy,” Muzzie says sullenly, his words a serpentine slur in his mouth. He’s eyeballing the dead cow above the bar now, too, and his glare says it all. Yeah, I hear him. And if he’s not careful, he’s gonna get popped in the kisser.

Conor shrugs. “It’s an okay arrangement,” he says. Then he makes a show of licking out the inside of his glass. He has a tremendously long tongue—the kind of tongue that might give Gene Simmons a run for his money—and there’s no mistaking the innuendo. The guy with the cross laughs, high-pitched and girlish, and so Conor stops, grins. Shrugs again.

“What about you, Kev? I’m sure you got plenty of tang in California, being a rock star and all.”

It’s not really a question and so Kev doesn’t really answer. He keeps his eyes focused on Conor, shakes his head slowly. Notices how quiet Muzzie has gotten, which is a bad sign. “I’m not a rock star,” he says.

“Come on, man,” Neck Cross says. “I need all the pointers I can get.” And Kev recognizes his role in tonight’s performance—he’s the guy who self-deprecates about his lack of sexual prowess for laughs. There’s one in every group. He’s probably not nearly as bad as he claims to be, but buy him another round and he’ll start moaning about how poorly endowed he is.

“You want a pointer? It helps to be rich,” Conor says, winking at the waitress who’s come to clear their empties. Kev vaguely remembers some story Conor told earlier in the night, one he’d only half heard, about how he had big plans for getting back into the energy business, wanted to harness the thermal power from the mine fires below Accident or something. He’d been a little too drunk to follow by that point. “I plan to drag this county into the future kicking and screaming,” Conor had said. “You ought to come see the plant I’m building outside of town.”

Kev had only nodded.

Now, he wishes Conor would talk about something boring like that, instead of this different business.

“If you like fish tales, you’ll appreciate this,” Conor says, and he launches into a graphic sermon about cunnilingus, about finding the g-spot and eliciting an endless series of earth-shattering, headboard-rattling orgasms. Parts of it sounds geographically plausible—just barely—though Kev has his doubts about any of it being true. He may not be a rock star, but he’s spent enough time between the sheets to know better than to believe any man-to-man sex advice that comes unsolicited. The guy next to Conor is clearly getting off on all this talk though—he’s thinking about practicing these tried-and-true techniques on his girlfriend, who has already taken the car and gone home alone. Kev can’t imagine that one letting old Neck Cross anywhere near her delicates tonight, no matter how worked up Conor’s story gets him. Not after the arm-wrestling fiasco.

Besides which, that’s not what this story is about. Guys like Conor don’t care about g-spots or the female orgasm. It’s not about pleasuring women. Or even pleasuring a woman. This story is about pleasuring Ramie in that read-between-the-lines sort of way. Conor is polishing the biggest trophy in his case. Rubbing Old English into the deepest notch on his bedpost. And it’s all for Kev’s benefit.

“Look at who I’m speaking to,” Conor says. “You know what I’m talking about.”

“It’s been a long time,” Kev says. “I can’t really recall. My relationships mostly all end the same way.” He punctuates his point by replicating a nose-dive plane crash with his hand. Fill in your own blanks.

That man ain’t talkin’ relationships, pardner; he means ruttin’, the steer skull starts to say, before Kev silences it with a dirty look.

“Hey, no offense meant, partner,” Conor says.

“Come again?” Kev says, and now he’s not sure who’s talking anymore.

Conor extends his hand almost graciously—the same hand that has, if you believe his story, brought Kev’s ex-girlfriend to the brink of death countless times—and it’s clear that he’s passing the totem. It’s your turn now, rock star. What stories of debauched sexual conquest do you have to share tonight?

Had he given it enough thought, Kev might have come up with a good rock and roll story, but it wouldn’t have involved sex. It wouldn’t have even involved California. His favorite story was more like a fuzzy memory from just after high school. The Mourning Afters. Conor had been there. Ramie, too. They’d all been playing at a bar near State College, one of their first really big out-of-town gigs, and they’d hit a streak of bad luck. At a gas station, one of them (Kev still wasn’t sure who, though he could take a guess) had locked the keys in the van, and they’d had to wait almost an hour in the rain for a locksmith, a little old guy who had to be on the verge of celebrating his very own bicentennial. By the time they got to the gig, it was late. A rushed sound check. No time to eat or drink or even take a leak. No time to fix their misspelled name on marquee out front either. The club owner threatening to dock their already meager pay. And Kev, feeling the first hints of fuzz at the back of his throat, practically begging the guy for something to wet his lips—an iced tea, a bottled water, anything.