TWO POEMS by Yuki Jackson

BLACK GRANDDAUGHTER CALLS JAPANESE GRANDMOTHER

I hold the phone

and my hand shakes.

I ask her why is it I’m not invited.

She has no answer.

I’m too black to be shown.

I knew before I asked her.

I knew she didn’t want to show me to her neighbors.

Now hear the dial tone.

My mother danced to soul

under the light of a disco ball

and never returned to

kneel on a bamboo floor.

THE HOTTENTOT VENUS CAKE IN SWEDEN

The room is full of white people in a cold place.

A government sponsored event.

They smile and use a knife to cut her open,

a life-size thick black female body

with an African bug a boo face.

They plate pieces of her,

lick her black icing skin,

fork to their lips, saying mmm, delicious.

Her inner flesh is red, perhaps red velvet,

classic American southern favorite.

A black male Sambo artist

created the installation.

With each hack,

the artist would cry for effect.

One white man’s hands shake

as he cut his piece away,

ashamed.

Why did he do it?

The prime minister cuts the clitoris of Hottentot Venus.

A white woman whispers in the black man’s ear,

your life will be better after this.

- Published in Issue 18

ON INTERSTATE 89 NORTH by Kerrin McCadden

I don’t know how close I was.

I was not paying attention to him

or his raised middle finger, which

he was tired of holding up,

his face lowered out the window at me,

glass down, even though the air

was freezing in upstate Vermont.

I have sped past, unthinking, it’s true.

I have sped past so many things.

How many miles until I know what I have done

is always the question. For a minute,

I thought I should be afraid

and watched him in my mirror in case

he sped to catch me. I have sped past and have been

unthinking so many times I want

the world to know. Once, a man leaned out

a passenger window and fired his gun at the sky

as I sped past. One time, a deer jumped

across my hood, which was accelerating,

while my son and I belted out,

Why do you build me up (build me up)

Buttercup, baby

just to let me down.

And nothing was the same afterward.

He grew, next, into someone

I’m desperate to track, to keep from harm,

to follow into the underbrush, wearing

orange vests or branches, depending.

The man crouched down in his fast, small car.

He stayed in line and left the highway

without closing his window.

Which was when I knew I was still alone.

A sign: one semi-truck cab hauling identical cabs

—one climbing up on the next, identical.

I know I was not wrong.

The way one carried the next, as if knowing

there was no other way to go.

And each was precisely like the other

so I craned my neck as I sped past them, too,

in case they, too, were astonishing.

- Published in Issue 18

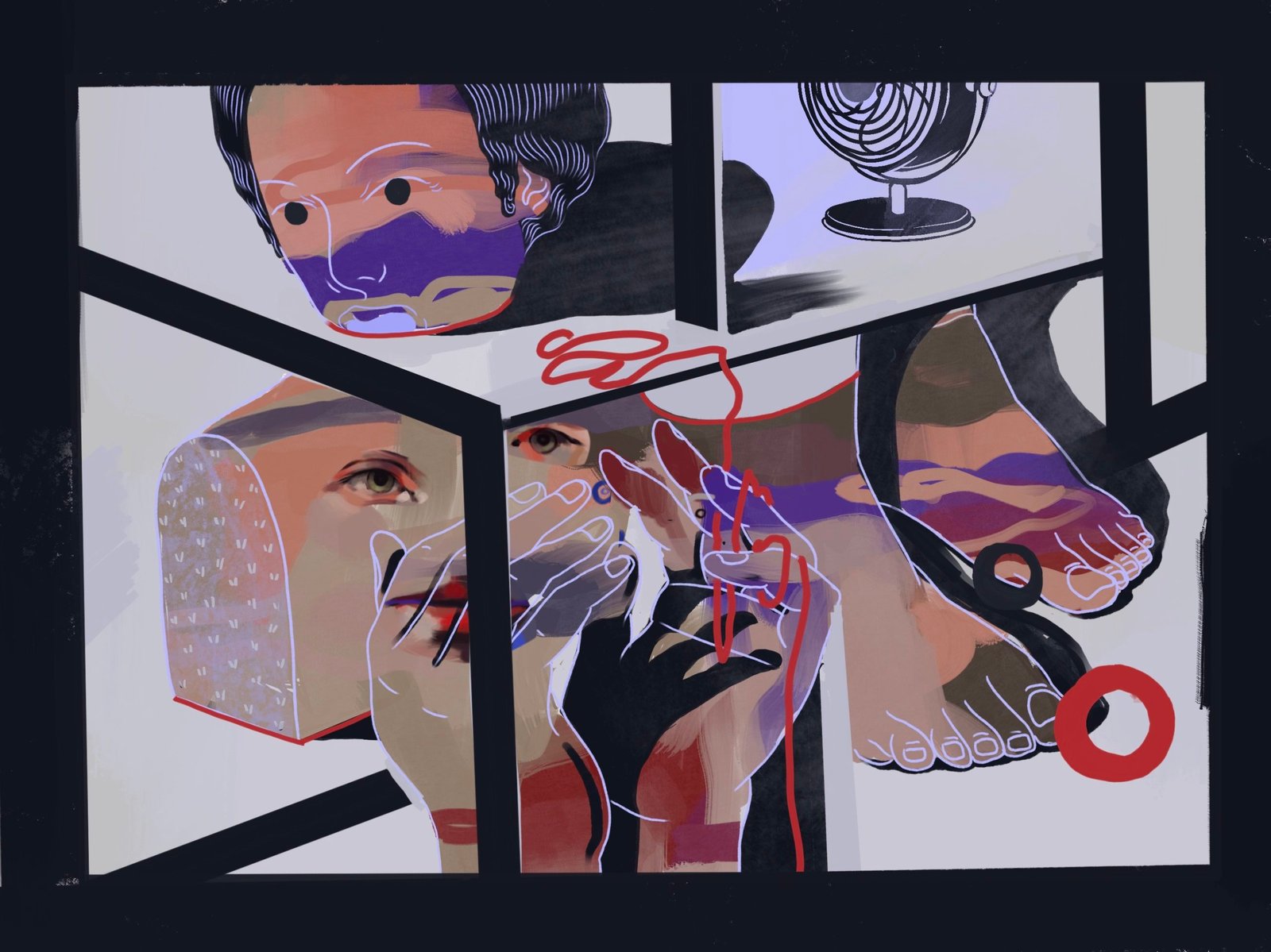

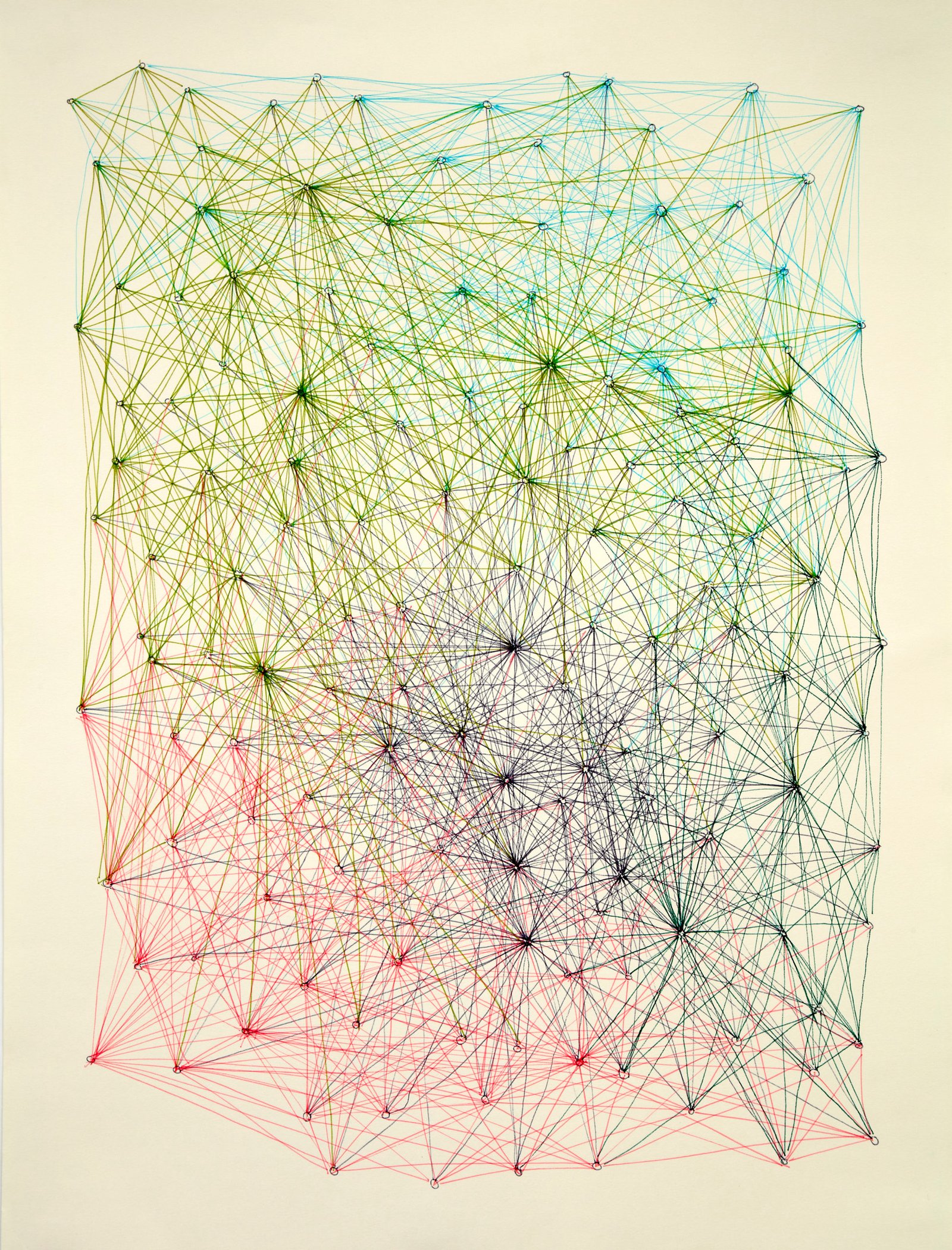

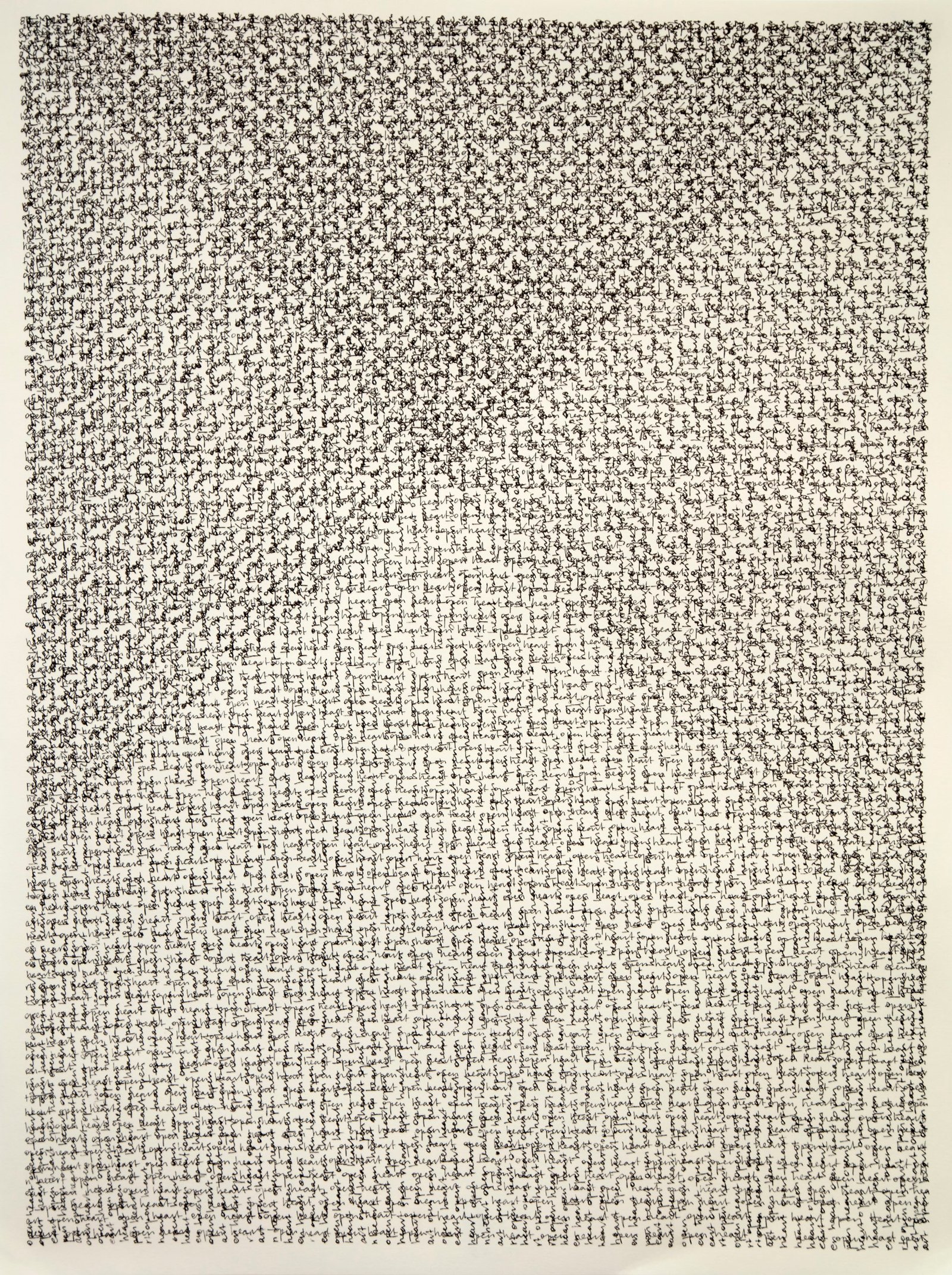

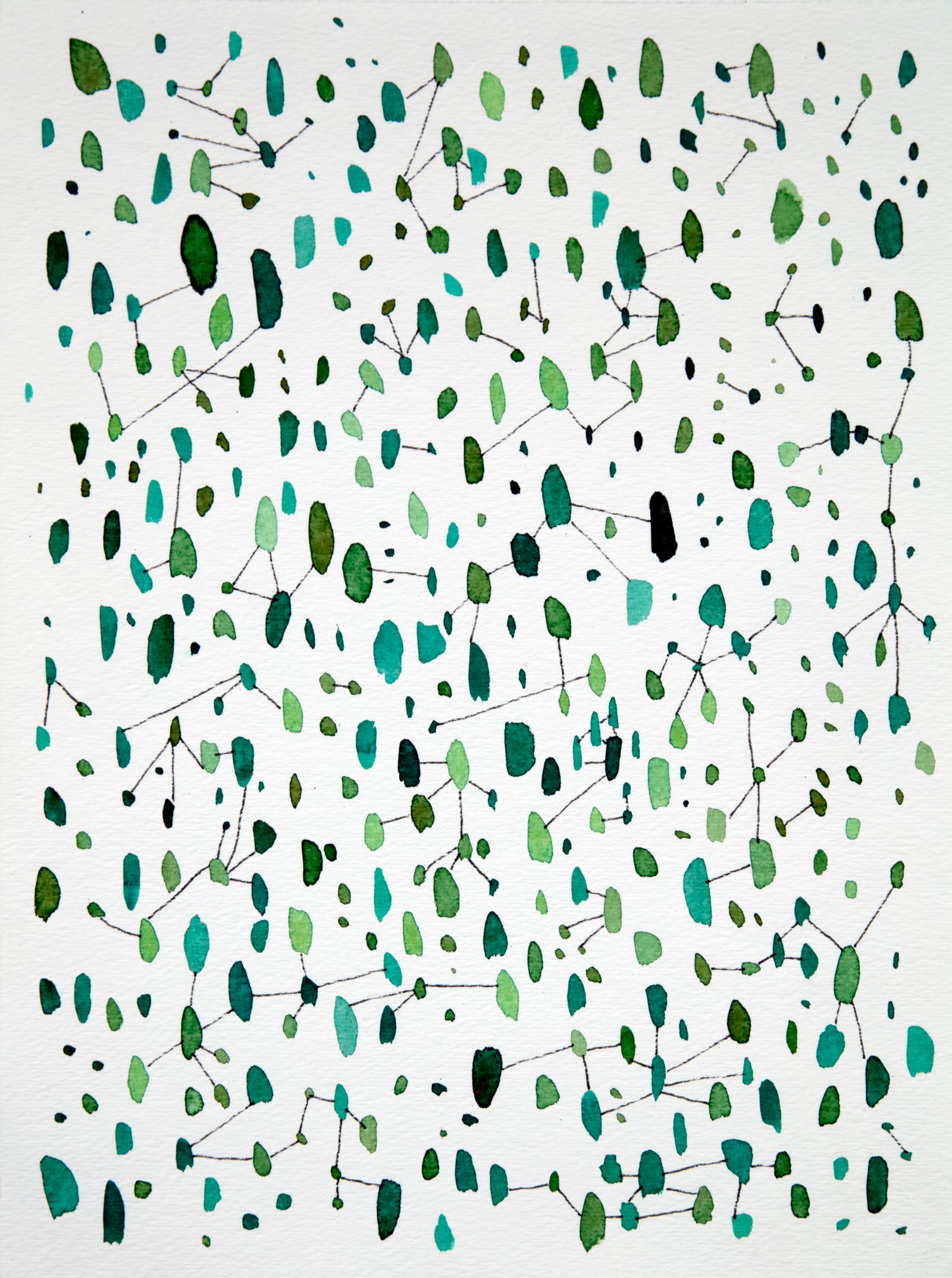

ARTWORK by Lynnette Therese Sauer

Everything Connects, ink on paper, 18×24″, 2018

Meditation XXIII (open heart), ink on paper, 18×24″, 2020

Everything Connects, watercolor on paper, 9×12″, 2018

- Published in Issue 18

JONAH WAS A PROPHET by Ottavia Paluch

but I’m just this tiny little thing

that was too quiet to become a prophet myself.

In the ocean, I’m not bothersome. Above it,

I exist and pretend not to. You forget who

you are after being swallowed. It’s weird, thinking

like this. You say things like home to a whale who

has already found one. In the digestive system, all you can do

is swallow and pray. You want to be cast out, like a fish.

Look at this world, trying to get above the trees.

I know nothing but the fact that we are fish, not saplings,

or that I will never reach the top of the mountain. Still,

I keep trying. Otherwise: no point. That’s not

the first disappointment I’ve had, which is to say that I

was the first, the one who stole the whale’s heart

because mine wasn’t pure enough. Did I choke on Eve’s apple?

If I yank on God’s vocal cords, will he sing me a hymn?

I don’t know. I’m not Jonah. Just a wannabe tidal wave,

a stranger. Scratched in God’s throat.

- Published in Issue 18

TWO POEMS by Patrycja Humienik

let the wind take care of it

crack the door, a window, let the air crack

open the books stacked & strewn, too many

to read in the clutter of one life,

let blast into the burnt expanse of forest

in my mind: each day the mirror

invites me beyond the need

to be liked, into noticing:

slopes of collarbone, bowl of pelvis,

what i am being moved toward: an image

of myself, running out the car and toward

the singed trees, smell of gasoline

faint but clinging—

pluck a softness

i am belly up beneath the dogwood plucking petals

when night comes out sprawls out beside me

they say, if you want a name

i have a fissure

night knows i long for a new name

night’s pronouns are they/them

i nod we toss

voices in familiar lilt &

scatter

they say, you are swooned by seeming ground

what is beneath that?

i glue stamen to stigma

pollen’s lip-lock untethered

botany of another wish

to-have to-do

the shattering into

once upon a time

in an alley, city gave night their quiet back

at what cost i do not ask

night is matter of fact: no matter

how much salt

is in your head you still have

a body

- Published in Issue 18

TWO POEMS by Jared Harél

KIN

(after Joseph O. Legaspi & Larry Levis)

Mother and smother are such similar words,

I can’t help but wonder if it’s by coincidence

or design. Same goes, I suppose,

for father and farther, though I’ve tried with my kids

to be present and knowable, no flicker

of myth, but like a Midwestern turnpike

lapped in steady light. Last night, my mom called

to tell me I don’t call her, though I could tell

through the cellphone that each line

was rehearsed. I could tell she was parked

outside Pathmark or Foodtown while my father

practiced takeoffs out of Republic Airport—

his pale Cirrus curling the traffic-

controlled skies. Last night, my son beat my ass

in UNO—a barrage of prime numbers

and primary colors, then a Wild + 4

put me to bed. Not bad for a four-year old

who sleeps cat-like across our pillows

to nuzzle the fantasia of my wife’s midnight hair

while I get skull-stomped by tiny bare feet.

How will my subconscious calculate

these improprieties? My father, a good man,

flies farther from me daily. We see each other

the way a field spots a peregrine

migrating south. My mother left me

another voicemail today. In UNO, the objective

is to be free of all cards, to detach

from the very contours of the game—but I remember

after he won and yelped quietly with delight,

how my son’s small hands pressed

the scattered cards together, both together

and towards me to reshuffle the deck.

BIRTHDAY

When my daughter turned seven,

she missed being six.

She didn’t want, she said,

to leave her old self behind.

And I, who had turned seven,

then eight, and many more,

sat on the edge

of her warm twin bed

and said, you take it

all with you, you bring all

your selves with you

into the future. I don’t know

what I believe, but I think

she believed me.

I told her nothing is ever lost,

and kept repeating it

till she rose in her nightgown

in the morning dark.

- Published in Issue 18

READING by Austin Araujo

How he reads the paper, his frail

then firm exhalations gliding along each word,

breath dancing a sentence’s waltz

and driven spin just below my ear,

swaying in the quiet of a house

otherwise buried beneath the din of my thoughts.

The labor of my own reading is silent,

corralling all of these book’s voices in my head,

refusing to let any out into the pasture

of the room while his tongue’s soft percussion

clicks in time with the folding

and unfolding of his brow. Each comma

gives him a chance to suck in more air,

the noise of which sends my attention

careening from the page, away from its castles

and systems of magic, and toward his measured

gasps that move me between fascination

and disgust like the sounds of a loud chew.

The muscles in his face must twitch then stiffen

out of habit. No. He has only made

this practice of meeting the printed word

recently, turning the newspaper’s box scores

and block quotes into speech, morphing his voice

into music not his own but in his key.

My father blowing quarter notes

into this pasture, this field, this meadow,

while the farmhands in my skull sigh

at what seems like wasted work: keeping

the boy and his wizard inside the fence.

- Published in Issue 18

THREE POEMS by Sara Elkamel

FEAR & IRRIGATION

They promised to give me the song’s weight in gold

so I carved the song in granite.

We put my songs in the fruitless garden.

Look at the light pouring there! you gasp,

digging around the cold

hard trees, rubbing their barks with milk.

I’ve carved all I could so I make more milk.

From the silver lake

you cry tonight’s desire

would split stone, rouse spring;

we sit by the cold numb songs:

these temples without doors.

I try to confess I know nothing about trees—

that I’ve always feared my songs

had the wrong kind of flesh—

but hoarse, you whisper Look at the light

pouring there & I must protect god

from my doubt. My lack of imagination.

I ask you to be god. I lick the prehistoric salt map

off your back, wave to the lost

pilgrims, the finches, the green horses galloping

from the next hurricane.

I count on my fingers to make sure

all the nights have had days.

I bark at the hours

songless. Afraid you will love me less—

afraid I will singe the new vines

around our waists.

FIELD OF NO JUSTICE

Though they will be reborn

each morning with the sun,

the dead remain obsessed

with the image of a single rose

by a crocodile’s open mouth.

A wail from the corner of the room

usurps the room.

Give me a mouth; I want to talk!

said the dead woman to the scale.

The heart on the scale is the heart of a sparrow.

My heart is the heart of a sparrow!

The sparrow was unremarkable; I cannot give you her name.

When I fell, she switched my heart for hers.

Mine was a clay heart the size of the sun.

Ask the sun, just ask the sun!

The sparrow’s feather heart is not my heart.

My heart knew nothing for certain.

Loved nothing for certain.

My clay heart did not know its own name.

My clay heart envied goslings their nests.

Envied mothers their sons.

Smothered every fire before its hour.

My clay heart cursed the heart of my mother.

I stayed a child to have a child.

I kept everything secret.

My clay heart licked the milk off the mouths of little children.

I chewed the hair off my knuckles to make the hands usable.

I tried to be a woman.

My clay heart thawed one night, I saw it.

I gave a boat to a boatless man, and at the lips of water took it back.

I wrapped the heart of my love in white muslin cloth and buried it with the others.

I made a remedy for remembering and drank one half in the morning and one half at night.

I couldn’t move.

I gave myself running feet. Even remember how I did it. I scrapped sand off my

toes and mixed it with pulverized red pepper. I spooned it into the river even

though they said this causes a person to run from place to place, until she runs

herself to death.

I couldn’t move.

The prayers I whispered into the walls bounced back.

I am not pure, I am not pure, I am not pure, I am not pure.

They weighed the wrong heart and found it

lighter than a feather.

To the field of reeds!

said gently the 42 gods of the feather.

There was water behind the door.

But my heart,

I said—

Find the sparrow,

said Osiris, stroking softly the crocodile.

The sparrow soared freely

above the cliffs

& the light fell on all of us.

SCHEHERAZADE AS NILE BRIDE [CONTRAPUNTAL]

after Yasmine Seale

|

The lost maps show |

We were all equally far from love and |

|

there’s no mercy |

hiding in the branches of rivers |

|

anywhere, |

so I excavated |

|

even the darkest hours. I fought |

an ancient fear |

|

to resolve the problem— |

of a woman being a person |

|

I hemmed a thousand nights with stories, |

trying not to die, then I thought |

|

but the night has never been a stable thing: |

What if stories were not endless? |

|

What if you begin to love that which |

Might kill you? What if your story |

|

Rewrites you? To escape I |

riddled the plans of men. I |

|

trapped water between my palms, |

silenced myself, made a new map, |

|

locked myself away in the eyes |

of a river with no eyes, and I thought |

|

of all the words |

not a single word survived but |

|

Then I found |

inscribed on the riverbed |

|

trilling in water: |

I found a manuscript, |

|

a marvel— |

where all the characters, |

|

In thousands of stories, |

were women, and unnamed. |

|

To become many women, |

I named them all after me. |

|

The Nile waxed our beautiful backs. |

What a gruesome end: |

|

All of us made brides |

(the translators wrote) |

|

of the night. |

But what if we told another story? |

|

We winnowed songs from the lungs of |

the river |

|

god who |

sang eternally of women who |

|

refused to die. |

refused to die. |

- Published in Issue 18

I FED MY HUSBAND MY EARS AND FLED by Diedrick Brackens

I left the sky forever and became

nurse to fish that frequent muddy water.

I buoy everything lonely and pregnant.

my family was here before legs

or seawater carried them. some leapt early

to be reborn under my skirts. others were tossed.

I am headless without my children.

my mind is the moon.

I am an aching creek, a loin of lake.

my innards spool the earth.

droughts dry liquid flesh, the mudfish

and flatheads; they breathe air and live, die, or leave.

somewhere else, my grandchildren take and eat

distant cousins, fins and heads removed.

they throw what is perfectly good away. most beg

grace from father and son, and sometimes

a ghost resembling me.

they forget my restless body broken,

and instead imagine flight, stardust,

lakes on fire, mathematics. some know

they all return to me, that heaven

is a muddy riverbed.

- Published in Issue 18

MY RUSSIAN TEACHER NAMED US by Meghan Dunn

She named us Yuri and Sergei and Boris.

The first verbs we learned were to smoke, to drink,

to live. We were thirteen years old. We learned

through repetition. I smoke, you smoke,

he or she smokes. We live. She named me Masha,

Mashinka when I was good, Mashka when I was bad,

which was often. We memorized charts

of endings. How neatly the language

fit together, like the nesting dolls

she carried from Russia in a suitcase,

Ded Moroz and his granddaughter

Snegurochka, nestled inside each other.

Everything worth having, according to her,

had been carried from Russia in a suitcase,

except for Levi’s jeans and ballpoint pens.

She named me Slovar, which means dictionary.

She promised us, one day, she would take us

to Russia, suitcases filled with Levi’s jeans.

We could sell them for one hundred USD a pair,

she promised. She never wore jeans.

She wore leather mini-skirts, orange or purple,

and matching turtleneck sweaters with high heels.

She had great legs. She liked to sit sideways

at her desk, legs crossed to one side. She liked

the lights off in the classroom except for

a small desk lamp, its glow circling her head

like a spotlight. She named Steven Bledny,

which means pale. She named him Peasant

when he spoke with a Ukrainian accent.

She wore brick red lipstick, a permanent smirk.

One heel dangled from her foot as she crossed

her legs. She liked to tell us the dirt on Peter the Great,

on Anastasia. Her large square glasses shone,

her high rounded perm circled her head

like a halo. She showed us a movie about Rasputin

and the czar’s hemophiliac son

and Bledny almost fainted at the nosebleed scene.

She told us how Catherine the Great

had a machine built so she could fuck horses.

She didn’t say fuck, but we understood,

or thought we did. She started every story,

I know you think I’m lying. We never

thought she was lying. We chanted after her,

kuda ty idesh. Ya idu domoy. Where are you going?

I’m going home. She promised to tell us

how her family escaped Russia. She used

the word escaped. She promised to tell us

if we all got an A on the quiz

and we did. I’m not in the mood, she said.

She was never in the mood. She never

brought us to Russia. In the dark,

she wrote all thirty-six letters on the board

in swirling cursive. She named the letter

she liked best, the pretty letter. Once,

when we were bad, she left the classroom.

Through the window, we could see her walking

across the parking lot, her high heels clicking.

She got into her car and drove away.

The lights were off. It was winter outside.

We remembered the song she taught us,

the one she made us sing over and over.

Pust’ vsegda budet solntse, pust’ vsegda budet nebo,

pust’ vsegda budet Mama, pust’ vsegda budu ya.

Let there always be sun, let there always be sky,

let there always be Mama, let there always be I.

Each line had a matching hand movement.

We had practiced it a hundred times.

We believed everything she told us.

Her name was Olga but we never called her that.

We sat in the dark and waited for her.

- Published in Issue 18

DAPHNE PURSUED BY APOLLO by Sophia Stid

A story told this many times becomes the forest.

No beginning, no end, no longer a narrative but the air

we breathe. For centuries, a woman with a name

rises from her sleep—becomes a tree—rains back down

again into her rest. One myth for how poetry began:

a man, reaching. Violence. Myth: Apollo finds the tree

inside of a woman. Apollo translates fingers into leaves,

hears a voice and calls it wind. I am not interested in Apollo.

I am interested in the father-god who could not stop

the rape but could turn his daughter into a tree—

what kind of power is that, and how does it still river through

our world? Why does nobody ask these questions? I carry more

keys than I need. Walking home from the library late, I thread

silver teeth through my fist. I am not a tree, and I am asking.

- Published in Issue 18

- 1

- 2