HOLLYWOOD FOREVER CEMETERY by Hannah V Warren

Los Angeles, CA

dear hollywood Snapshot

Paint me indian Peafowl

persuade me a Succulent

my sister & I are lonely

the dead are Good

company

only when I’m alone with Them a lonely with them

Horsehair pattern & revolt

we argue over Mallards

Violence vs Nurture don’t vomit in the

Rosebushes

don’t sleep in the

Crypts

don’t piss on the Geese

don’t desecrate judy garland

don’t cremation don’t steal johnny ramone’s Guitar

& use it as a

Vibrator

rip : strawberry clover & bur clover & wall barley

we Snake our hats Fill them with pink

Peppercorns

lavender scallop a daisy chain to Death

my sister & I fill Perfume Bottles with blood

& sell it to

tourists

we knock Bones on tin cans & call it Religion

we remember all the ways we are

Similar

& the Remembering hurts

- Published in Featured Fiction, Issue 34, Poetry

THE GATEWAY by Laura Wolf Benziker

Mina, in the passenger seat, was lulled by the vibration of the car. Her skull knocked against the tempered glass in a not-unpleasant way. Her eyelids sank and darkened, then flicked open every few minutes. She saw exotic colors: swaths of glowing terra cotta, deep violet shadows, a sky so blue she only half recognized it. Then she dropped drop back into hypnagogia.

“Mina,” came Wayne’s voice. “Miiiina…” Wiggling fingers crept up the side of her neck. She flinched and opened her eyes. She turned to look in the back seat: both kids had fallen asleep. Their heads lolled at painful-looking angles.

“Why’d you wake me?” she said, with mock anguish.

“I lost the signal. You need to navigate. Plus, just look at this place!” Her husband swept a hand as though presenting the canyon to her. “I dub you Mina, Queen of the Carpathians!”

Mina smiled and took the paper map of the Utah park out of the side pocket of the rental car. Impossibly grand vistas gave way, one to another, as they rounded bends in the road. It felt like they were on a giant’s stage, weaving their way between set pieces. The looming rocks seemed to have personalities; they were definitely not inert. Mina could feel them looking at her.

The family had flown in on a red-eye from Boston. It was only a couple hours’ drive from the artifice of Las Vegas to this otherworldly place. Mina had planned the trip meticulously. A seven-day tour of the Southwest. She had booked stays in Zenith, Hale, Monolith Valley, Mesa Azul, and Archway. They would explore the majesty of nature together.

They pulled up to the park entrance. The kiosks were unmanned this time of year. Wayne drove under the low roof of the mid-century modern structure, and the park was theirs. Mina placed her finger on the map at the spot where they were. She picked the first green star along the route that indicated a trail and directed her driver to it.

Wayne swerved to the side of the mountain road and parked in a narrow gravel crescent that hugged the cliff edge much too intimately. They woke the kids and they all got out, groggy for their first hike. They were met with a burst of chilly air that brought the sweet smell of desert. Wayne and their teenage son, Liam, loped across the road. Mina clutched five-year-old Jamie’s hand, looked both ways, then followed. A rock wall faced her, and she looked up. She had to lean back to see the top of it, and she was hit by a wave of vertigo. She steadied herself with a hand against the rock and waited for her heartbeat to slow. A car zoomed by. She hurried Jamie to the trail, which was nearly vertical. The four of them went up sandstone steps, squeezing and releasing the steel handrails. The rails had thick dark rust all around, except for the top, which was worn smooth as a horse’s back, bright and silvery. The trail snaked up the bluff, which was dotted with a few tenacious juniper bushes. Mina was last in line, a human buffer between her child and certain death. She took a quick look behind her, at the earth dropped away, then clutched the railing, dizzy.

They reached a plateau and the handrails ended. Mina stopped to take a puff from her inhaler. Liam looked back at her.

“You good, Mama?

“Yes,” she said between labored breaths. “It’s the elevation.”

The trail continued along the side of a cliff with nothing to prevent a hiker from tumbling to their doom. Liam and Wayne went along without a care. They were both tall and lanky and had matching gaits. Wayne’s hair was graying; his curls spiraled wilder every year. Liam’s smooth skin stretched over his rapidly changing bone structure, perfect but for a spray of acne. He possessed the calmest nature of the four of them, a levelness, even at the top of a cliff. Jamie frisked and flailed, oblivious to the danger. When he started to follow his dad and brother, Mina called out, “Nope. Absolutely not.” She took him firmly by the hand. She yelled to Wayne, “You go ahead. We’ll hang out around here.”

“Come on,” he said. “It’s just a trail.” She shook her head. “Suit yourself,” said Wayne.

Mina steered Jamie back the way they had come. At the top of the stairs, they came upon a smooth patch of red sand. Jamie picked up a stick from the brush on the side of the trail.

“This is my drawing stick,” he said, looking up at her from under his own mop of curls. He squatted down and drew in the sand, a shaggy creature with fangs. “It costs a dollar to draw.”

She pressed an invisible coin into his palm. He handed her the stick, expectant, but she was too tired to make the effort.

“You draw one for me. I already paid.”

Jamie agreed. “Mama, I have a quiz for you. Which is the strongest, Dracula or the Wolf Man?”

“The Wolf Man,” said Mina.

“No, the answer is Dracula. Because he can fly.” Jamie drew a figure swooping down at the shaggy creature. “It’s Dracula versus the Wolf Man! Dracula attacks with Bloody Fingers and Wolf Man counters with Howling Wail, Oooooh ooooh! Dracula’s defense is lowered! He attacks with Frozen Fangs! Grrrrrrrrr. Wolf Man is now stunned!” Jamie stood frozen with a grimace on his face, then continued drawing. “Dracula attacks with Coffin Creep, but it’s not powerful enough. Wolf Man attacks with Claw Shot. Pew Pew Pew! But he forgot that that move does 50 percent damage in recoil! They’re both destroyed!” He brushed the images violently from the red sand.

“But I thought that Dracula was the strongest?” said Mina.

“Yep,” said Jamie.

They stood and listened to the wind wailing in the canyon.

“Can I play video games now?” said Jamie.

Mina looked back at the trail Wayne and Liam had disappeared into. It will probably be a while, she told herself, before they are back.

They made their way down the steps, Mina in front this time. The cars on the road below looked like toys, the roar of their engines muted. Partway down, Mina stopped. On the mountain face opposite them stood a deer. It was miraculously stable on the sheer slope, and from the angle where they stood it appeared to be floating.

“Look at the deer, Jamie!” Mina whispered. It seemed to be watching them. Jamie gaped at it.

“It’s an augur,” he said.

“What?” she said.

“It’s a kind of deer.”

“Okay. Let’s go down. Hold the railing tightly.”

*

Back at the parking area, they opened the glistening white doors of their rental car and climbed in. Mina tilted her seat back and gazed out the sunroof at the clouds going by. She dug a novel out of her carry-on. Jamie sat hunched in the passenger seat, playing his handheld video game. There was still no sign of Wayne and Liam.

Mina read two chapters, then got the feeling she’d forgotten something. She put the book away, and checked her bag for medicines, phone charger, first aid kit, inhaler, lip balm. It was all there. Jamie switched out his game cartridge for a different one.

Mina took off her bracelet and fidgeted with it. She slid the silver beads between her fingers in a rhythm that matched her breath. When she was very young and would go on long rides in her family’s Volkswagen bus, she had a favorite puzzle she played with. It was composed of sixteen sliding plastic tiles, pink and white, in a yellow frame. If you aligned them right you were rewarded with a picture of Bugs Bunny leaning nonchalantly on the shoulder of a cranky Daffy Duck. The tiles slid smoothly, with a satisfying amount of resistance, making a delicious SSHHH sound. She played with it for so many hours the bright pink color had worn off to white in places under her small thumbs. She always wanted so badly to match the tiles in the right order, to make a complete picture out of chaos. The only problem was, for the tiles to be able to slide, there had to be one missing.

Mina looked at her watch and was disoriented. Then she remembered the time zone change and set the hands back two hours. Too much time had passed. Something must have happened.

You’re imagining things, she thought. Don’t think about it.

She leaned back again and looked out the windows. The clouds settled across the sky in layers, straight and flat as the layers of rock in the bluffs around them. She composed a text to her husband, but it failed to send.

Another half-hour passed, and she invited Jamie to clamber into her lap. She interlocked her knuckles across his little belly as he battled the villains of the universe. His curly head leaned against her breastbone, behind which her heart beat frantically.

The sun was getting low in the sky when the back door opened and Liam flopped into the car. Mina gasped, then felt a wash of relief. Jamie climbed back into his booster seat. The passenger door opened and Wayne swiveled to fit his long legs in.

“You were gone quite a while,” Mina said. She was embarrassed to hear the quaver in her voice. “How was the hike?”

“The hike,” said Wayne. “Wow, yeah. It was really something.” He stared out the window. Reddish dust had settled on his cheekbones and eyebrows. And there was something strange about his face.

Mina looked back at Liam, “What did you see?” She tried to look him in the eye, but he wouldn’t meet her gaze.

“We saw mountains,” he said.

“And?”

“Um, there were some deer on the side of a cliff.”

“We saw a deer too!” said Jamie. “It was an augur!”

Mina started the car, turned on the headlights, and had no choice but to keep going in the direction they were pointed. Into the dark passageways between mountains. Eventually she found a pull-off area large enough for her to turn the car around.

They exited the park and took the road to the village under a sweeping arch of sunset. They rounded a bend and saw the sign for their motel, The Desert Rose. Its low angled black roofs seemed to hover in midair. It was a moment before the buildings themselves came into focus. It was a trompe-l’oeil. The walls were stuccoed in sand and rust colors, tinted in layers to mimic the grand landscape in which the motel nested.

*

The kids entertained themselves, opening and closing the sliding glass patio door of the motel room to block each other’s entry, then racing around the building on the moat of pristine white gravel to do it again. After a few minutes Jamie slammed Liam’s hand in the door. Liam howled and swore, and Mina half-heartedly reprimanded Jamie. She was relieved it hadn’t been the other way around. They ate dinner in the motel restaurant, where they were the only customers. By then they were beyond exhausted, so they got into their pajamas as soon as they returned to the room. As they settled in for the night, Mina went over their schedule for the next day.

“We can hike for a few hours in the morning and have lunch. We should leave for Hale by two so we can drive in daylight.”

“I like it here,” said Wayne. “See if we can get this room for an extra night.”

Mina looked at him. “Okay,” she said, “If you really want to. But it’s too late to cancel the room at Hale.”

“Have them push it back a day. It’s the off season. I’m sure it won’t be a problem.”

Mina frowned, but she made the calls. You had to pick your battles.

They took turns brushing their teeth. Three of them sprawled on the king bed, with Jamie curled up on Wayne’s lap. Liam sat in a chair in the corner, a remote look on his face.

“Let me tell you a tale,” said Wayne in a theatrical voice:

Twas brillig and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe.

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“What the heck are you talking about?” said Jamie.

“You remember this one, right Liam?” said Wayne, raising and lowering his eyebrows maniacally.

“Yeah, I do,” said Liam quietly.

Beware the Jabberwock my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Wayne grabbed Jamie by the shoulders and tickled him fiercely. Jamie shrieked and kicked with delight. Mina looked over at Liam, who was softly reciting the rest of the verse:

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun the frumious

Bandersnatch.

*

After breakfast they began a hike, a leisurely stroll along a gorgeous sparkling stream. Jamie found some cholla cactus skeletons, called them magic wands and gave one to Liam. They wizard-battled as they bounded down the trail. Mina beamed, watching them interact. With the ten-year age gap and the difference in schedules, the two of them were usually like ships in the night.

The trail ended at a waterfall. It cascaded in a silver fringe right over the trail, which was kept dry by a rocky overhang. Moss and wild succulents hung down in tendrils. It was a miniature fairy-land in a secret nook of the desert. Mina found a dry rock several yards away, sat down and took granola bars out of her backpack. She watched the kids goofing under the waterfall and snapped some photos. They splashed each other viciously, squinting and laughing. Liam leaned out over the railing and doused his head.

“Snack?” said Mina, and held out a granola bar to Wayne. He sat next to her, looking in the opposite direction, where the mountains loomed.

“Not hungry, thanks,” he said. He drummed his fingers on his knees. His eyes darted across the landscape. His eyes looked gold. They had always been brown. Hadn’t they? Mina wondered. Do people’s eyes change color over time? Maybe Wayne’s had changed years ago and she had never noticed.

“I think I’m going to head to another trail,” he said. Mina felt the joy drain from her.

“But it’s so nice spending time as a family.”

“There’s plenty of time for that,” he said. “I want to challenge myself, do some serious hiking.”

“We can all go together. You can choose the trail.”

“I don’t think you’re up for it. No offense, but you would slow me down.”

Mina opened her mouth to respond, but her mind had gone blank. Wayne trotted off the way they had come, out of sight in just moments. He didn’t even say goodbye to the kids.

This is just like last June, she thought. She tried not to remember.

Mina took her time regaining her composure. The kids were having so much fun they hadn’t noticed.

After a while the three of them headed back along the trail. The kids kept goofing off. Liam swung Jamie up over his shoulder, then pretended to throw him in the stream. Jamie screeched and Liam set him back down. Then Jamie stood stock still.

“Where’s Dada?” he said.

“Well,” said Mina, “he wanted to do a hike by himself.”

“Oh, okay!” said Jamie. Liam looked up at the tall mountains.

*

Back at the parking lot, they got in the car and Mina drove aimlessly. When they passed a field of deer, she slowed down to get a better look. Their ears were huge and alert, their noses dark. They had white bands of fur around their necks, which gave the impression that their heads were somehow detached from their bodies. Some of them loped, anxious about an unknown threat. Others stood still as statues, and watched them as they drove past, their heads turning in unison.

The road narrowed as it gained elevation, and Mina felt more and more ill at ease. Her chest tightened and her breathing strained. Every time they went around a bend, she imagined the road disappearing and their car pitching into nothingness. She searched for a place to take a break. She found a scenic pull-off and parked. The kids scrambled from the car, and Mina dug in her bag for her inhaler. Her nervous system calmed as her lungs absorbed the vapor. Her breath slowed, and in a couple of minutes she felt better. She walked to the edge of the parking lot and looked out at a huge flat sandstone plain. It turned out to be a perfect spot, with relatively little danger of plunging to one’s death.

The kids played a sloppy game of chase. They grabbed and yanked on each other’s sweatshirts. Liam swung Jamie around by the wrists, and even though it didn’t look safe, Mina let it go. She walked across the sandstone in a meditative state. The wind kicked up red dust in delicate eddies. Some of the fine powder settled into the gaps between her white shoelaces. It would stay there for months. Mina tugged her cardigan tighter around herself and took in the whole horizon. The jagged surfaces of the mountains stood out in sharp focus, astonishingly clear for such a far distance. It really was a stunning place.

The kids discovered the rocks were so soft that they could hurl them against the ground and watch them explode in a burst of sand. Liam, with his lithe, chiseled shoulders, was especially good at this. He flung them, he smashed them, he hucked them with a feral look in his eyes. After a couple minutes of that she told them to stop. She was sure it wasn’t good for the mountain. She walked to a sandstone wall whose surface appeared to be moving. She went closer and realized that grains of sand were spilling down the side in a slow and constant cascade, with no apparent catalyst. She held out her hand, palm up, as if she were coaxing a baby bird. The fine grains formed a pile in her hand and then spilled between her fingers. It crumbles if you fight it, she thought. It crumbles if you do nothing.

The kids were hungry again, so Mina drove them to the visitor’s center. Liam and Jamie scarfed veggie burgers with soggy pickles on the side. Mina got herself a yogurt parfait, but when she took off the plastic lid, she realized she couldn’t eat.

“Mama, I have a quiz for you,” said Jamie. “Who’s my favorite person in the world?”

“Umm…Liam!” she said.

“Nope!” said Jamie. Liam leaned toward him in mock indignation. They were all used to this.

“It’s Dada!” said Jamie. Liam’s face clouded into a scowl.

Mina felt her heart clench.

“Liam,” she said, “Is everything okay?”

“It’s like we don’t exist,” he said. “Like this whole trip is just for him.”

She had tried calling Wayne. She had tried texting him. What was she supposed to do?

The visitor’s center was closing, so she told the boys to put their trays away.

They piled wordlessly into the car and headed back in the direction of the motel. When they were almost there, Mina’s phone buzzed.

They backtracked and picked up Wayne on the side of the road. Jamie happily recounted the events of the day to his father. Mina was fuming. She thought about what she would say to him. But there was nowhere private where she would be able to talk to her husband. She didn’t want to upset the children.

As they were getting ready for bed, Wayne said, “Let’s stay another night. I like it here.”

Mina looked at him, weighing her words.

“We have to keep moving,” she said. “Don’t you want to see all the beautiful places we planned to see?”

“We can skip them,” he said. “This place is special.”

Wayne loomed over her, and behind him on the wall his colossal shadow quivered. Mina was a small person, smaller than their fifteen-year-old son. Wayne was six-foot-three, wiry but strong like a coiled spring. He weighed almost double what she did. This had never seemed like a major concern, but all of a sudden, she was afraid.

She canceled the room in Monolith Valley, forfeiting the deposit, and pushed back the room at Hale one more day.

In the middle of the night Mina moved up against Wayne’s back and put her arm across his ribcage. He did not wake. She felt a subtle vibration from his body. Maybe it was the half-dream state that she was in, but Mina felt like her husband had shed his gravity. Like if she took her arm away, he would hover above the bed.

*

The next morning when Mina woke, Wayne was already dressed.

“I’m getting an early start hiking today,” he said.

“What?” said Mina. “What about us?”

“You can do your own thing. You’ll have fun.”

“We want to spend time with you. The whole family, together. Wayne, I’m trying to fix things!” A series of images appeared unbidden in her mind: she and Wayne as a young couple, playing Scrabble and laughing with a group of friends in their shabby apartment; Wayne sleeping on the couch with baby Liam on his chest, his large hand resting gently on the baby’s red onesie-clad back; herself in heels and a cocktail dress, standing at the top of the basement stairs, speechless, looking down at Wayne in his bathrobe, grin on his face, whiskey glass in hand; a shiny rental car not unlike the one they had now, Wayne in the driver’s seat, pealing around a corner and grazing the guardrail as she stood clutching the kids on the side of the road, dizzy from the heights under the June sun.

“There’s nothing to fix,” he said. “Everything’s fine.” He grinned at her with his gold eyes.

Mina sighed. “Well, we have to at least set up a meeting plan.”

“Visitor center at four,” he said.

Mina nodded, and Wayne was out the door.

Mina scoped out another hike. The kids didn’t have the same vigor as the day before. Liam’s shoulders hunched forward and he looked at the ground. They stopped at a river, where the kids halfheartedly threw pebbles.

Feeling like she owed them a new experience, Mina took them to the visitor’s center gift shop. The objects for sale were so appealing with their saturated illustrations and sleek graphic design. Mina let them each pick out a fridge magnet, little portraits of the majestic canyon they were trapped in. Jamie couldn’t decide, so she let him pick two. Months later, procrastinating dinner, Mina would stand and slide the magnets around on the refrigerator. She would slide them apart and back together, switching up their order. Their earthy pull would bring her back down to the ground, and she would feel a heaviness in her chest. She would slide and slide them and wonder what went wrong.

They stayed until the gift shop closed at five, and Wayne never showed. They drove back to the motel in silence.

Wayne called while they were finishing up dinner. They piled back in the car and found him waiting at the visitor’s center, standing in the shadows. Mina quivered with rage.

Mina said quietly, “We’re leaving at nine tomorrow.”

“Mmm,” said Wayne.

That night, Mina’s sleep was strained and sweaty. The covers felt like wet bandages, and the room smelled of vinegar. She wavered in and out of consciousness, waking sometimes to the white noise of her family breathing. Once or twice, she heard muffled yelling from the bathroom. Wayne was next to her, sleeping right through it. Liam’s voice was deep, and his rage was raw.

*

Mina woke when it was still dark. She had a sense that she had to go outside right that second. She slipped silently behind the heavy curtain and slid open the glass patio door.

The gravel was cold and sharp under her bare feet. She felt ill in her stomach. It was like how she would feel when, as a teenager, she would make herself eat an apple at 4:30 a.m. before early swim practice. She looked up at the dark, sequined sky. Along the ridge of the mountain glowed a crackle of ruby that grew as she watched, and melted into sugared tangerine, and then gold, which dissipated into the soft beige of dawn. It happened in a matter of seconds. And she knew.

She packed her own bag, then Jamie’s bag. She gently woke Liam. There was an artificial glow from the corner of the room where Jamie was already up and hunched over his video game. The three of them got dressed quietly so as not to wake Wayne, and went up to the lodge for breakfast. The kids wolfed down their plates, and went back for seconds. Mina sat and gripped her coffee mug. She breathed in the steam and hoped the porcelain would warm her hands. She tipped in a container of cream and watched it swirl before it dissolved. Looking at her kids, she had never felt so lonely.

When they got back to the room, Wayne was brushing his teeth. He wore a white motel bathrobe over his underwear.

“We need to go now,” Mina said. “It’s a four-hour drive to Hale.”

He gargled and rinsed his mouth. “I think we’ll stay here a few more days.”

He turned his head but did not make eye contact. He doesn’t see me, thought Mina. He will never see me again.

She hustled Jamie across the cold parking lot and got him into his booster seat. She opened the trunk for Liam to load a suitcase. He stopped and looked at her with what she recognized as fear. “Why isn’t Dada coming?” he said.

Mina’s chest tightened. “I don’t know,” she said.

Liam’s eyes went wide. He spoke softly, “It’s the cave, isn’t it?”

“What cave?”

“He told me not to tell you.”

“I won’t tell him you told me. Of course I won’t,” she said.

Liam grimaced, bent his head forward and grabbed fistfulls of his hair. He walked a few steps away, then turned and came back. Regained his posture and took a breath.

“Okay,” he said. “We hiked for a while after we left you, and we got to the top of the mesa. I was looking out at the view, enjoying it. Then Dada called me over.”

Mina’s heart pounded. “We have to load up the car,” she said. “Keep talking.” They crossed the parking lot together. The sun had risen higher since breakfast, and threw dramatic purple shadows on the mountains.

“I followed his voice. I went around this pile of boulders, and Dada was on his hands and knees in front of this hole in the rock. He said we should check it out, and he crawled in.” Mina held her breath as she opened the door open for Liam, and they walked through the maze of motel corridors. The tessellated pattern on the carpet gave Mina a wave of nausea. She caught Liam’s arm and clung to it.

“He called me from in there. I said I didn’t want to go in, I have claustrophobia. I thought he would come out in a minute, because how big could the cave possibly be?”

“Hold on,” Mina whispered, bringing a finger to her lips as she opened the door of their room. They gathered up the dregs of their belongings. The door to the bathroom was closed. They stepped back into the hallway and the door clicked shut behind them.

“I couldn’t tell how long it had been,” Liam said, “but it felt like forever. I was getting scared. But I was not going in there. That place had really bad vibes. So I yelled into the cave. I kept yelling and yelling, and finally he came back. When he came out, he had this weird look on his face. But he was smiling, with his teeth all showing. It was so weird. So weird. Then he looked right at me and said, ‘It’s the Gateway.’”

Mina couldn’t speak.

“He just stood there in front of the cave. If I hadn’t been there, I don’t know if he would have left. I told him we had to get back to you and Jamie. He said something I couldn’t understand; he started mumbling. But then he snapped out of it. We hiked back. When we were almost at the car, he told me not to say anything to you about it.”

“Oh, no,” said Mina.

“I think he’s been going back there,” said Liam.

A chill shook Mina’s body. “Thank you for telling me,” she said, and hugged him tight.

She closed the trunk. Liam got into the back next to Jamie, leaving the passenger seat vacant for his dad. Vibrating with fear, Mina walked back across the parking lot, through the maze of hallways, and checked the room one last time. The bathroom door was open, and the room was empty. She walked back to the car in a daze. She got in and turned on the engine.

“Where’s Dada?” said Jamie.

Mina closed her eyes and spoke carefully, “Dada decided he’s going to meet us in Colorado, honey.”

She took a moment to breathe; to force her sadness into a nook in the back of her mind. She laid out the map on the seat next to her. She made sure her phone and sunglasses were handy. She checked that the kids were buckled, and she looked out the window at the motel. Her eyes widened at what she saw. There was a figure in a white robe standing on the dark, low-angled roof. He stood, with his arms outstretched, looking up at the mountains.

Mina put the car in gear and drove out of the parking lot. Slowly, deliberately, like a puzzle piece sliding into place. She couldn’t help looking in the rear-view mirror. In the reflection she saw her husband, face tipped back, rising off the roof of the motel, into the vault of the sky.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Fiction, Issue 33

RUN by Katherine Vondy

There is a room at the end of my hallway. Its door is always shut. Shut, but not locked. Inside the room there is a girl. Fifteen, dirty-blond hair, thin. Most of the time she lies on the bed, headphones on, listening to something with lyrics, mouthing vaguely along. She holds a pen against the pages of a spiral-bound notebook, college-ruled, though its light blue lines are irrelevant as the girl uses the paper for drawing, not writing. What does she draw? It’s hard to see from the doorway. She never leaves the room.

*

My apartment in the city is not large but it is lovely and was well worth the down payment. Its hardwood floors are pristine, and the molding around the doorways is elaborate yet tasteful. It is a relic of an earlier, better time, though maintaining the illusion of a bygone age has not come cheaply. I’ve made significant adjustments to the apartment’s design and floorplan in order to make it functional in today’s world while still retaining its original Greek Revival charm. The heavy cornices and double-hung windows are a perpetual reminder that the present cannot help but be rooted in the distant past.

This aesthetic is one that my clients frequently aspire to, but few of them have the funds to realize it. They find themselves settling for the clean, relentlessly-modern look: a look that is less beautiful, but more affordable. As a result, many of my projects have a sameness to them. In early adulthood I’d imagined that becoming an architect would offer more opportunity for variation; however, many of the beliefs we have when we are young prove to be misguided.

But understanding the misconceptions of youth is one of the benefits of getting older. It’s an unexpected satisfaction—like the sense of self-worth I earn from my professional successes, or the feeling of peace that comes over me when I run. I run in the park early in the morning, often before day has even broken. The park is at its quietest then: I rarely see another runner, let alone another woman. It’s a habit I’ve maintained for years, barring the occasional break for illness or travel. While there are slight differences each day that I run—chilly one morning, prematurely stifling another; tree branches bare and sparkling with ice in the winter, the summer turning them matte and green—my jogs usually coalesce into one amorphous entity of recollection, like water molecules gathering in the upper atmosphere to form a cloud.

*

I’m running down a gentle, muddy hill, not far from the botanical garden, enjoying the way gravity makes speed effortless, when another, slower runner fails to move sufficiently to the side of the path. Her left shoulder collides with mine as I pass her, and at the same time her feet skid on the slippery, wet dirt. There’s an oh!, then a thud, and then a more strained vocalization. Glancing back, I see the other runner on the ground.

I bring myself to a halt and turn around, retreating to the place where she has fallen.

She’s about my age, and she isn’t crying, not with any gusto, at least, but a few tears fall down her face, presumably from pain. She hunches over, holding her right ankle in both hands, as if she wants to make sure it does not escape her.

“Are you okay?” I ask, a question with an answer so obvious it shouldn’t need to be asked, but in this sort of situation it must be posed nonetheless.

“I’m okay, but I don’t think my ankle is,” she says.

“Is it broken?”

“I don’t know. No, I don’t think so. But how would I be able to tell?”

“You probably need an X-ray,” I say.

“Yeah,” she agrees, wincing.

“Can you walk?”

She shakes her head. “It hurts. It really hurts.”

“Do you have a phone, so we can call for help?”

She shakes her head again. “I don’t bring it when I run. I don’t want the distraction.”

“Oh,” I say, my voice judgmental, even though I don’t bring my phone when I run either, for the exact same reason.

I look around. It is one of those typical early mornings in which there are no other runners in the vicinity. In fact, there are no people at all. There’s a narrow pink line on the horizon from the sun waiting below it, but otherwise the sky is dark.

“Here’s what we’ll do,” I say. “There’s a coffee shop outside the park, about half a mile from here. It opens at 6:00 a.m., and it has to be near that now. They must have a phone. Or someone who works there must have a phone. I’ll run there and call 911. Someone will come here to help you soon.”

For the first time since I saw her fall, the woman looks frightened.

“You’re going to leave?” she asks.

“Just to get help,” I reassure her. “It won’t take long.”

“No, please don’t! Can you just stay with me? Someone else will show up soon. Another runner. Someone who has a phone.” But as she speaks, a few more droplets appear on her face. Not tears; rain.

“Look, the weather’s getting bad,” I say, pointing upwards. “People are going to stay indoors. Who knows how long it will be until someone else appears? And I don’t think it’s good for you to sit in the rain while you’re injured. I can get to the coffee shop in five minutes. It’s the fastest way to get you help.”

The woman tries to stop me. “No, no,” she pleads. “I don’t want to be left here alone.”

But I’ve already started to jog away. “I promise I’ll come back. As soon as I’ve called, I’ll come back.”

*

I don’t come back.

I do run to the coffee shop, just as I said I would. It is 6:02 a.m. when I arrive, and the barista nods understandingly and points me towards the office in the back. I call 911 and describe the emergency to the operator.

“A woman is injured on the jogging path,” I say. “She fell and did something to her ankle. She can’t walk, and she’s alone.” I describe her exact location, in the downhill part of the trail, just past the entrance to the botanic garden. I offer descriptive information, even though the fact that the woman is sitting injured on the ground should be enough for the EMTs to identify her. Early 40s. Curly brown hair in a ponytail. A blue and purple windbreaker. No phone. I do not mention our collision. I do not say I promised to return.

The operator tells me she’s dispatching a team immediately.

“Thanks,” I say.

And then I go home.

*

I walk to the end of the hallway and rest my hand on the doorknob of the closed door. When I twist my hand, the knob turns smoothly. I push the door open.

The girl inside looks up from her notebook. She doesn’t recognize me.

“What?” she says. Her voice hovers between bored and annoyed.

“Nothing,” I say.

She stares at me and I stare back. She isn’t alarmed by the situation. It’s as if she expected it all along: to be in this room, drawing, indefinitely.

I slowly shut the door. I assume she turns her attention back to her pen and her paper when I am out of sight.

*

I work on the twenty-fourth floor of a twenty-five-floor building downtown. I step into the elevator and rise up with other professionals in well-tailored clothes. Some are my colleagues; others are attorneys, accountants, actuaries. High-rises like mine are notable for the diversity of industries that can be found within.

My office is small but has one well-placed window, next to my desk and parallel to my right shoulder, which allows me to sense the outside world without needing to look directly at it. I slide my mouse back and forth on its mousepad to awaken my computer. The monitor flickers to life and I sit down in my ergonomic chair to embark upon the day’s tasks. Architecture is not traditionally recognized as a hard science, but it undoubtedly requires a scientific mind. My job requires diligence, attention, and an organized method. There are emails to write, blueprints to lay out, presentations to outline and then draft and then re-draft. It necessitates complete focus, a kind of concentration that disallows any interruption, no matter how minor. I excel at this kind of thought. I am well-versed in building walls of all kinds.

There is much to do—there always is—but today I’m on an especially tight deadline, as we are courting a big client, a successful advertising agency looking for a new space for their expanding team. I’m tasked with creating an elaborate deck that allows the founders to understand how the right design choices will directly lead to huge gains in revenue. I amass images of vaulted ceilings, arched doorways, impressive pilasters, and arrange them into a compelling architectural story. I don’t think about the injured runner until I am packing up to leave my office. Then, as I pull on my jacket, the morning’s incident reappears in my memory.

Perhaps I hurt her—but only briefly. Only insignificantly. She will be fine without me.

*

I ask the girl in the room if I can see what she’s drawing.

She doesn’t say anything, but she holds up her notebook, its inner pages facing me.

She’s not an especially skilled artist, and her blue ballpoint pen isn’t the most nuanced medium, but all the same I recognize what she has drawn. Who she has drawn.

Without question, it’s me. Not me today, the adult, but me as I looked thirty years ago, when I was her age. That dark, messy hair. Those wild eyebrows, those pre-Invisalign teeth that made my lower lip stick out further on the right side than the left. Refinements to small details of a house’s architecture can change the identity of the entire property, and the same is true of people. If I did not know this used to be my face, I could not have guessed it.

“I know her,” I tell the girl.

“Uh huh,” she says, either disinterested or disbelieving.

“No, I’m serious. I do.”

“Okay. How do you know her?” the girl says, pulling her notebook back.

Explaining that I am the girl in the picture, just older, seems too complicated, and possibly unnecessary. “Well, I heard a story about her,” I say instead.

“So you don’t really know her.”

“I guess not,” I say, and maybe it’s true.

She flips the page idly and starts drawing on a new sheet of paper. “What’s the story?” she asks.

“It’s from a long time ago. It’s kind of sad.”

“Sad how?”

“Sad in the way that you don’t really recognize at the time. More of a retrospective sadness.”

“What happened?”

“The girl you drew, she grew up in this small town, right? And she had a friend she was very close with. They were best friends, I guess. And they had a lot in common. A lot of similar interests. The same likes and dislikes. So it wasn’t that surprising when they liked the same guy.”

“And you said they lived in a small town. There probably weren’t that many guys around to begin with.”

“No, there weren’t. I heard there weren’t,” I agree. “So, the girl in your picture and her friend, they fell for the same guy. And it shouldn’t have been a big deal, because they were so young, and there were sure to be many other guys. But it was also because they were so young that it seemed like such a big deal. At that age, the stakes of everything are very high. Or at least they seem to be when you’re sixteen. And then when you’re older, you get more perspective, you know?”

“No. I don’t.”

That’s fair; she can’t know these kinds of things, the things that only become knowable after years and years.

“So these friends liked the same guy,” she prompts me.

“Yes, they both thought they were desperately in love. With Adam.”

She doesn’t react to the name, but why should she? She hasn’t met him yet.

I continue the story. “And he was a nice guy. And so were the girl and her friend—they were nice people, too. But even nice people can end up in hurtful situations.”

“What situations?”

“You know. Normal situations, the situations that happen to everybody in high school. Crushes and confusion and heartbreak situations.”

“But what happened? Whose heart was broken?” she asks. A ray of soft sunset light pushes through the crown glass windowpane and sneaks across her cheek.

I’d like to think it was both of us, but I am not sure that it was.

*

We’re hanging out at the mall after school, like we always do. We walk back and forth down its sprawling length, going into the same stores and looking at the same merchandise over and over, as if the slouchy boucle sweaters and alternative rock CDs and dangly bauble earrings aren’t the same sweaters and CDs and earrings we looked at yesterday and the day before and probably the day before that, too.

When we are tired of walking, we go to the food court. She gets egg rolls from her favorite fast-food place and I get fried zucchini from my favorite fast-food place, and we sit on the plastic stools that are bolted into the floor, leaning on the dingy tables that are also bolted into the floor.

“You know who I wish was here right now?” she asks.

“Adam,” I say. I wish the same thing.

“Yeah,” she sighs.

We dip our fried finger foods into dipping sauces. She has sweet and sour and I have marinara.

“Maybe he’ll ask you to prom,” she suggests.

“Or maybe he’ll ask you.”

Adam is a junior while we are only sophomores, and therefore not allowed to go to prom unless an upperclassman asks us. But we think it’s a possibility, at least for one of us. We are both advanced in science and were placed in an eleventh-grade chemistry class, which is how we met him. Sometimes I will end up paired with him for a lab, or sometimes she will, and on those days, we cannot wait to put on oversized white coats and safety goggles and measure various liquids into pipets and heat solutions up over Bunsen burners and hope it turns out to be the day our most romantic dream will come true.

She and I have the same dream.

It’s not so far-fetched; neither of us are quiet or retiring in his presence. We don’t merely admire him from afar. We talk and joke around with him, and, in what we hope is a unique benefit of knowing us, his lab grades whenever he partners with either of us are significantly higher than when he is partnered with anyone else, which we can deduce because our chemistry teacher always hands our reports back in order from the best score to the worst. We feel certain Adam enjoys our company; or, if he hasn’t quite gotten to the point of enjoying it, he must, at minimum, appreciate it.

We’re still eating our egg rolls and fried zucchini when something amazing happens. As if the power of our desire is great enough to manifest physically, Adam walks through the mall’s automated doors and into the food court.

We gasp with joy. Such a coincidence cannot possibly be just a coincidence. It’s too unbelievable, that we would be talking about Adam (though these days we are almost always talking about Adam) and then he would appear, as if we’d summoned him (though he works at the mall, at a sporting goods store, and so is admittedly here regularly, which is one of the reasons we are also here so frequently). But still, the timing seems auspicious. This coincidence must be more meaningful than most.

He sees us and waves, then meanders over to our table. Our hearts spasm.

“Hey,” he says.

“Hey,” she says.

“Hey,” I say.

“Want one?” my friend says, holding out her container of egg rolls.

“Sure,” he says, choosing one and biting it in half.

She was quicker than I was, and now, if I offer Adam some of my fried zucchini, it will seem that I’m unoriginal. If I don’t, it will seem that I’m ungenerous. It’s a miserable conundrum.

“Do you have to work today?” I say, desperate to keep the momentum of the conversation going, bypassing any talk of zucchini. He nods, then glances at the big clock that dominates the center of the food court.

“Shit, I’m late,” he says to both of us. “Thanks for the egg roll,” he says to my friend only.

We wave at his back as he heads in the direction of the sporting goods store. When we look at each other, we are ebullient, but she alone is triumphant. She alone has managed to give him a gift.

*

There is joyous news at work: we’ve landed the big client, the advertising agency we’d been chasing for months. I’m assigned to the account, and introduced to their team as one of the brightest minds in the industry.

“Not to mention,” a corner-office executive adds proudly, “one of the most dedicated. No kids, no husband. She doesn’t even go on dates. Nobody else will be there for you the way she will.”

I suppose I could consider the irony of the statement: that I am a person who is known for her commitment to corporate entities, but unable to offer the same reliability to individuals. But for now, I simply shake the hands of everyone from the client’s team, telling them I’m thrilled to be collaborating with them, that I see big things in the agency’s future. The atmosphere in the conference room is one of optimism and excitement.

An assistant pulls a bottle of bubbly from a refrigerator; it is stocked with an impressive supply of identical bottles in preparation for events such as this one. With delight, he pops the cork. The champagne is doled out into plastic flutes and the group of us, our team and their team, mingles as if the conference room is a high-end cocktail lounge.

“We’re very excited to work with you,” a woman from the client’s team tells me. Her pale pink blouse matches her manicure exactly: either she pays incredible attention to minute details, or she loves pale pink. “We’re looking to create something truly special with our new building. Everyone else in our industry is creating these bare-bones, contemporary spaces that are so antiseptic and alien…but we really want to distinguish ourselves, we really want to set ourselves apart with a different character. We’d love something more classic. That has more of those old-fashioned details that add texture and personality.”

“I love hearing that,” I say, and I do. My heart swells at the possibility that maybe this time—this time—the client will actually be able to follow through with their vision for a contemporary space that still pays homage to the past.

Then the client transitions into a more personal mode. “So, where are you from? Or did you grow up in the city?”

I shake my head and tell her the name of my town, and a soft film of recognition descends over her face.

“Really? That’s so interesting,” she says. “My college roommate was from that town. In fact, maybe you knew her! It’s a small town, isn’t it?”

“What’s her name?” I ask, though I am having one of those eerie moments of premonition that hits some of us upon occasion, in which we already sense the events that are to come before they have a chance to unfold.

The woman says the name of my friend, the sound of those syllables electric, even after all this time. If I didn’t know such things were impossible, I might think I had invoked this woman into existence.

“No, I didn’t know her,” I say.

*

A few days later, Adam asks my friend to prom. I know, intellectually, it is not because of the egg roll, but I cannot stop replaying that moment at the mall in my mind, as if everything about our futures hinged on those seconds in the food court. Something had transpired, even if I couldn’t define it, that had shifted the balance of the world, or at least my world: when my friend and I seated ourselves on those bolted-down chairs we were equal, but by the time we stood up this was no longer the case. Somehow, she had gained an advantage.

“You’re not mad, are you?” She looks at me, worried, as I pull my Algebra II textbook from my locker.

“No.”

“Because I didn’t do anything.”

“I know.”

“So you’re okay with it, then?”

“Okay with what?” I say, although I already know what she means.

“If I go to prom with Adam.”

I close my locker door in an effort to delay my answer.

“Because if the situation were reversed,” my friend continues in an uncharacteristically tinny, high pitch, “and he’d asked you, I would want you to go. I would be happy for you.”

The thing is that she can’t know that. She can’t know how she would feel in those circumstances; she can only know how she would hope to feel.

I know what the right answer is. I know what I need to say.

I say it.

“I want you to be happy,” I tell her. “You definitely have to go. Go to prom and have a great time.”

“You’re sure it’s okay?”

“I’m sure.” My throat is getting smaller and smaller; words are trapping themselves inside it and I can’t say any more.

“I’m so relieved,” my friend says, her voice dropping back into its normal register, “and you are the best.” I can tell she means it, but she seems not to notice that I can’t look at her.

In Algebra I stare at the board, where the teacher is writing lines of equations, but that’s just the direction my eyes are looking and has no bearing on what’s happening inside my mind, which is a twisting procession of questions that have no answers, or at least no good ones, like Is my friend more fun than me? Is my friend smarter than me? Is my friend prettier than me, is she more attractive, is she sexier?

At home, I stare at my naked body in the full-length mirror in my bedroom. It doesn’t look the way naked or nearly-naked women’s bodies are supposed to look, according to feature films and lingerie ads. My stomach is not flat. My hips are far wider than my shoulders, the lines that define my body between my rib cage and my thighs lumpy. Inside, my emotions slam together, trying to break through to the outside. It’s no wonder Adam did not ask me to prom.

If I am ever to be someone Adam could love, I must be better.

*

The interesting thing about running is that it moves one, physically, through external space, while internally, everything settles into stillness. The forces counter one another; they create equilibrium and balance.

The sensation is not so different from that achieved when one walks into a well-designed building: tranquility, serenity, and possibly even forgiveness.

*

The woman in the conference room does not have a sense for being deceived.

“That’s strange. I would have thought that in a town like yours, everyone would’ve known everybody else,” she says, guilelessly. “But I suppose some paths just never cross.”

“That’s true,” I say.

An awkward pause threatens our conversation. In the interest of maintaining an easy professional relationship, I say, “So, what was your roommate like? The one from my town?”

“Oh, she was lovely. Very kind and very smart. Though I’ll admit that I didn’t get to know her that well. We only lived together that first year of college, and she went back home most weekends to visit her boyfriend. It was one of those old-fashioned high school sweetheart situations.”

“I’ve never really believed in those,” I say, smiling.

The woman laughs. “They’re not like unicorns. They really exist! My roommate was proof of that. She left school after—oh, it was right around when everyone was starting to worry about Y2K, so it must have been our junior year—to marry that boyfriend.”

“She married Adam?”

The woman frowns slightly. “I didn’t say his name.”

“You did,” I insist. “You said his name was Adam.”

“But I couldn’t have. I don’t even remember what this guy’s name was.”

I shrug, casual and non-committal. “You must have remembered is subconsciously, because you said it. You said Adam.”

“I’m not sure,” she says, dubious.

“It’s too bad your roommate didn’t finish college,” I say, re-directing the conversation. “If she was as smart as you say.”

Now it’s the woman’s turn to shrug. “I don’t know. I’m sure she had her reasons. You have to do whatever makes you happy, you know.”

The conference room suddenly seems very dark, everyone in it more like shadows of people than people themselves. I feel like I’m going to fall down.

“So, she’s happy?” I say.

“What? I didn’t quite hear that.”

“So, she’s happy?” I say again, more loudly. “Your roommate?”

The woman starts a bit at the increased volume of my voice. “Oh, I haven’t talked to her in years, but sure, as far as I know.”

Looking around, I see that the plastic flutes are empty and people are starting to pick up their coats and bags. The corporate celebration is coming to an end. I gather myself; how strange that I had that momentary faintness. Perhaps it was the champagne.

“That’s wonderful,” I tell the woman. “And what a small world it is, that you knew someone from my hometown.”

“It’s definitely an unexpected coincidence,” she says, glancing towards the door. Most of her colleagues are beginning to trickle out.

“It makes me think it was meant to be, that we would end up working together on this project,” I say quickly, before she can leave. It’s important to reinforce the sense that our companies’ future collaboration is destined to be a success. “And it was wonderful to meet you,” I add, shaking her hand with its perfectly polished nails and releasing her from our conversation.

I think of the injured woman from the park. It’s been several days since she fell, and I wonder if she has forgotten that I broke my promise to her.

*

The girl is still drawing. I ask her if I can see her notebook, and she holds it up. It’s the same picture of the same face. My younger face.

“I know her,” I tell the girl.

“Uh huh,” she says.

“No, I’m serious. I do.”

“Okay. How do you know her?”

I still don’t know how to explain.

“How do you know her?” I say instead of answering the question.

“She’s my friend,” she says.

*

My friend wants me to go prom dress shopping with her. She asks if I want to meet up at the mall.

“Sure,” I say, feigning joy. “That will be so fun!”

“I’m thinking something long and green,” she says, which is unsurprising. Green is our favorite color, and if I were going to prom, I would also want a long, green dress.

We agree to get together at noon on Saturday—we’ll get lunch first, so we have the energy needed to sustain a long day of shopping—but when noon rolls around, I don’t go to the mall. I stay home, and when the phone rings, I don’t answer it. I don’t need to. I can already sense who’s on the other end of it: my friend, standing at the payphone in the food court, looking up at the big clock, her face worried, wondering why I am not there as I said I would be.

I don’t return the message she leaves on the answering machine, and when I see her in the hall on Monday, I keep walking as if I don’t see her, even when she calls my name. I do the same on Tuesday, and Wednesday, and so on.

After a while, so does she.

Prom comes and goes but now, in Chemistry, my friend and Adam are always lab partners. They amble through our school, smiling, fingers intertwined, and whenever I see them, my insides gnash together and I wonder what will happen to me if the tumult never stops. I am miserable without my friend, but my friend is happy without me.

I take up running.

*

I walk out of the room and shut the door behind me. Then I turn back, re-enter. The girl looks up.

“She’s my friend,” she says again, holding up the drawing, showing me myself.

She was your friend, I think.

She was your friend until Adam liked you more, and then she was not strong enough to be loyal to you. She said it wouldn’t affect your friendship—but that was a lie. She lied to you, and then she ran away.

*

The client is happy with our designs. To be more precise, they are happy with my designs, for I have done the brunt of the work, both conceptually and physically, that comprises the presentations we share with them.

“We love these details,” the pink-nailed woman says. “The placements and shapes of the windows, the arches of the doorways—they’re gorgeous. They’re reminiscent of an earlier time—a better time, I’d venture to say. The only thing is”—and here she flinches—“as we look at the estimates, we fear the project is a little more costly than we’re prepared for.”

My heart breaks as it understands that the design I have conjured for them is yet another beautiful dream edifice that will never be a reality. But my heart is harder than it used to be, so it only breaks a little.

“Of course we can come up with some more economical solutions,” I say reassuringly. “I’m certain we can design a space that will suit all your needs.” And I am certain. Designing spaces that suit all needs, all purposes, is what I do best.

*

The door at the end of the hallway is closed. I could walk down it, turn the doorknob, and see what the girl inside is drawing now, but I think it is better if I do not.

She will never get older, she will never age. She will never stop thinking the girl she draws is her friend.

Tomorrow, the park will be gloriously empty as I run, and as the sun threatens to make itself known just behind the city skyscape, the peace of my pounding feet will fill me, and the specifics of the jog will fade into every other jog, and I will not remember it at all.

- Published in Featured Fiction, Fiction, Issue 33

MAY INTERVIEW WITH SOPHIA TERAZAWA

When readers first meet the narrator of Sophia Terazawa’s novel, Tetra Nova, published by Deep Vellum Publishing in March, they have just been trampled by an elephant, returning to consciousness inside what seems to be the body of a panda. Soon after, the narrator tumbles again, this time awakening as Emi, a young girl with a backpack full of crayons that she must use to draw an exit from the chamber she has found herself in. Emi, as we soon learn, is not only Emi. She is also Chrysanthemum, her Vietnamese grandmother, and Lua Mater, a little-known Roman war goddess-turned-assassin-turned-performance artist—and she is here to guide you on Terazawa’s stunningly polyvocal, spectacularly non-linear journey through time, space, memory, and identity. (Non-linear, as in: the novel’s Table of Contents can be found nearly a third of the way through the text, on page 95.)

Expanding the bounds of what a novel can do, Tetra Nova reads like a dream journal written by a poet who is also a performance artist moonlighting as a translator excavating generational trauma. Plus, there’s a panda named Panda.

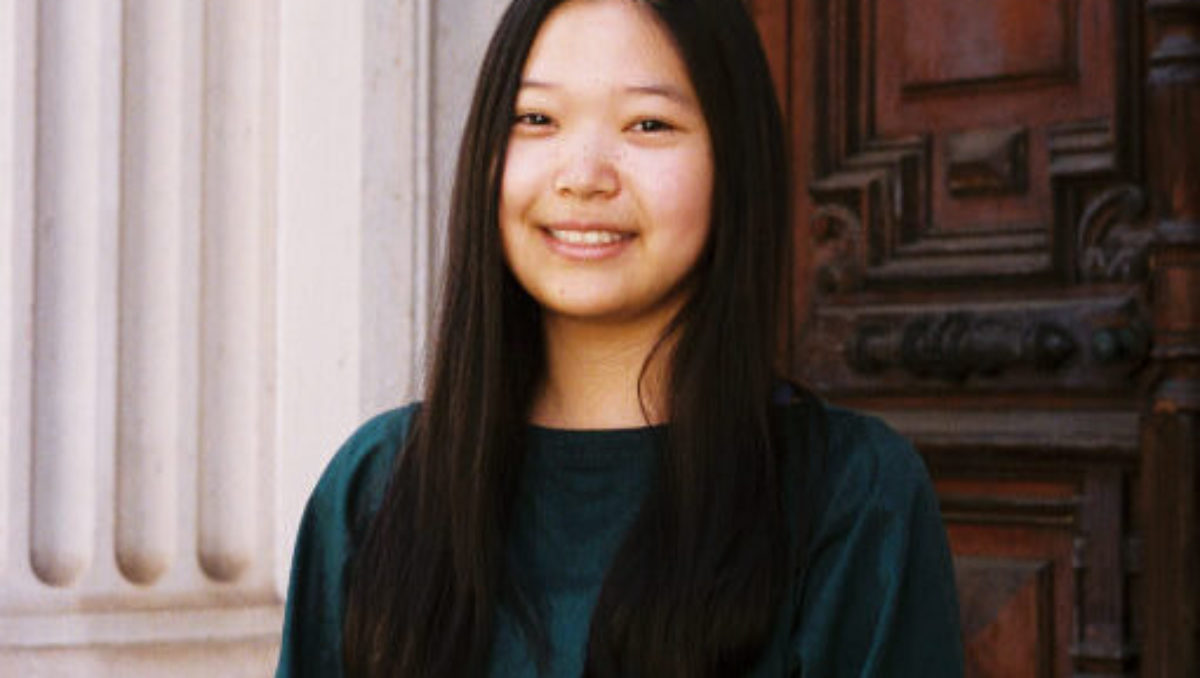

Sophia Terazawa is interviewed by E Ce Miller.

FWR: The form and structure that Tetra Nova takes are mind-bending. The agility with which you move readers through literal millennia of space and time, sometimes in a single paragraph, cannot be overstated. In your writing process, how do form/structure and content develop—do you find that your material naturally lends itself to a particular shape, or do you set out to navigate your characters through a non-linear, multi-form narrative from the start?

ST: Oh, thank you for opening with such a generous question! My mind bends continuously. It’s unnatural and natural both, this material that becomes a long hall of mirrors around all of my books. For Tetra Nova, the process arrived as one might now attempt to describe the occasion of a fractal: fern, snowflake, Golden Ratio… I don’t know where to land next with its momentum, but the “multi-form narrative,” as you’ve aptly picked up, is a great place to start. And maybe opera, too… In the shower lately, I’ve been practicing a karaoke rendition of “O mio babbino caro” with full range and emotion!

Okay, did I set about shepherding the characters through their marked spots of entry and exit? With this question, I think of Viewpoints by Anne Bogart and Tina Landau, on “soft focus” required of performers to navigate the span of a stage or “grid” with imaginary lines and topographies. How it felt for me: voices moving along this grid at varying rhythms and slants, a sequence of vertical and horizontal trajectories, a philosophy of lunges along the metaphysical plane, [See: Illustration by Robert Faires for The Austin Chronicle], and, of course, mosaic time. I really did have a film camera in my eye!

FWR: I’m curious about whether/how you relate to the (typically Western, North American) resistance to non-linear plots. It’s a curious resistance, at least in my mind, because it seems non-linear is precisely how most minds work. So much of our lives are spent in memory, anticipation, imagination, distraction, intrusive thoughts, etc., most of us are traversing massive expanses of time and space all day long, and yet there is somehow a rejection of that when it comes to storytelling. What did this nonlinearity allow you to explore as a writer that a linear plot might not have?

ST: Memory makes more sense for me in the dream world, especially without language. Here, cities often occupy my subconscious—nameless cities, cities at night… If the poetic impulse, more specifically an aubade, is awakening with relative shock or ecstasy to some wild, unknowable Truth, it’s our morning bird song. It’s a lantern for dawn. It’s the act of recalling: “I remember you. I remember how it felt to be loved by you, just yesterday.” And this becomes a triumphant return after the long exile of desire. Yes, memory as anticipation…

With this logic, on the other hand, I think about prose in terms of a nocturne, which in turn leads to the promise of silence: “I leave the soprano aria of you behind. I accept that you will never return. I close my eyes. No, goodbye. Let me sleep.”

Ultimately, nonlinearity arrives at such promises of memory’s obliteration. Thinking too much about Tetra Nova in terms of day or night, however, makes me want to murmur about Eden: “Please don’t wake me in this burning garden.”

Or maybe to Eros: “Where have you been? I’ve been waiting for your touch my whole life.”

Lulled to further abstraction… Perhaps the intersecting plots of my novel don’t want to say anything in the end. Only suspension… Finally, I think of John Cage who referred to Duchamp’s assertion of music as “space art” rather than “time art,” perhaps a fractional equation of space divisible by time, or perhaps laughter that doesn’t require meaning. Laughing is just laughing! I’m happy for our gift of forgetfulness.

FWR: Naming is crucial to this book. The characters frequently announce themselves by name. The refrain, “My name is Lua,” is repeated many times. At one point, Chrysanthemum, upon arriving as a refugee in Michigan, says, “Yes, my name is whatever you want.” You also write: “As I write through the multiplicity of what is possible or not, my name becomes whoever is reading this, yours.” I’m interested in any thoughts you might have on the significance of naming: what it is for a character to declare their name, what it is for them to give that naming over to something outside of themselves, etc.

ST: Lacan! The mirror stage! [Laughs.] The unified self and “Coronus, the Terminator” by Flying Lotus…

The scene in Bergman’s Persona, where the doctor observes about the actress, Elisabet: “The impossible dream… not of seeming, but of being…”

The unnamed dead of my mother’s country, which no longer exists in the Real of her imaginary…

The refrain of Mahmoud Darwish’s eternal banishment: “Write down: I am an Arab…”

The lines of lament merging between Vietnam and Palestine…

To declare a name, then, as June Jordan declared her stakes through poetry, mirrors the significance of becoming human and not simply seeming human amidst the smoke and mirrors.

My mind is ignorant in many ways, but around these meeting points of justice, I’m firmly planted alongside a collective life force within multitudes of mortal dignity. And what I fail to articulate clearly with this reply can be summarized, perhaps at the very least, with an assertion that Tetra Nova is my Name. And it’s your Name, too, if you allow it. Strange, the declaration of these names across time loops back to my mother’s name and your mother’s name. Hence, the force launches time across immeasurable distances. Hence, the astral plane of travel! Wow! Let’s go!

FWR: Much of the polyvocality of Tetra Nova is contained within a single character who is Lua, Chrysanthemum, Emi, and occasionally others. At one point in the novel, this character says, “I started to have a nagging feeling that the voices between my grandmother, Chrysanthemum, and my mother, Emi, were merging with mine.” I’ve heard that every mother/daughter story is a circle. Thoughts?

ST: Yes, circles are bisected by lines as well. A plot point compels the sweep of a body in angles of Vitruvius, and architectures of thought collide with architectures of narration. [See: Illustration by Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara, prefiguring Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Source: Ten Books on Architecture, Smithsonian.] Okay, let me try to reinterpret this in another way.

The square is set within its circle. Within the shapes are the rules of stage design. Within this design exists an elemental inscription of forces—wind, water, fire, earth—guiding the four corners of our planet back toward the center. The swordsmen of my father’s side, in The Book of Five Rings, might argue for our fifth element: Void, or the ether.

But I’m a simple thing with simple aspirations. Instead, I prefer melodramatic love scenes like the final declarative between Leeloo and Korben Dallas in the temple chamber of their heart, Mother and Father anchoring our profane and four-cornered worlds.

Watching this aforementioned scene had pushed me enough to orbit around the topic, and with a story, bickering between Aristotle’s concept of “potential infinite” and paradoxes of “actual infinite” compelling all points to wiggle. Love! Love! We want to shout.

FWR: Expanding on that question: At one point, readers are given the case notes from a technician at an institution where Emi is a patient. I’m curious how you think about this pathologizing of the polyvocal?

ST: Alright, so, in one of the hospitals of my past, I remember singing ALL of the time. It was insufferable; I was sorry for the revolving cast of staff and roommates. It couldn’t be stopped. And I remember eating a lot of cheese sticks during snack breaks. And I remember that somewhere amidst these iterations of asylum, Panda had been taken away at some point, as some sort of punishment. This made me Mad!

Therefore, what does the institutionalized memory say about pathology? I don’t think of “right” or “wrong” at this juncture because my commitment to the performance art kept us busy over those four extended residencies. We had roles to play and stage notes to take. It was a very serious time.

FWR: You write of the Vietnamese language: “…there is a word for unrequited love as a consequence of war through foreign dominance…” which is a line that just knocked me sideways. You also note that Vietnamese only has a present tense. In one of Tetra Nova’s “Citations,” you write of a photographer considering the D.C. Vietnam War memorial, quoting, “remembering does not come easily to Americans.” How do you relate memory and language? Do you think there is a quality to specific languages that makes their speakers more inclined to remember? Do particular languages lend themselves more easily to forgetting?

ST: I forget the best in English. My best self is in dancing. I’m inclined to feel that speakers know the gesture of a word before its utterance. As we move sideways, I invite us to return to the song, “In This Shirt” by The Irrepressibles, which had been played on a loop for the entire duration of composing Tetra Nova. And to the language of Complete Want, yes, the tonal mode of speaking inclines me more toward memory. It’s much easier to carry a melody in Vietnamese than in English. In Japanese, a syncopated rhythm is likened to cicadas… The best dreams are the ones in which I wake up singing.

FWR: There is also a point in your writing where the game Tetris and the English language are described similarly. If English is Tetris, what is Vietnamese? What about Japanese?

ST: Without English, time loses its container for me. To that point, Tetris has a start and stop point, much like spoken time. But neither Vietnamese nor Japanese operates like a game in my body. Marigolds perhaps come closest.

FWR: One of the central consciousnesses in Tetra Nova is Lua, this relatively unknown Roman war goddess who collected weapons captured from enemy combatants. Do you see language as one of these “captured weapons”? Is that something you ever consider as you write?

ST: Hmm, how spicy! A fabulous question! It is said that a mountain burns with the “elixir of immortality” by order of the Emperor, who is heartsick for the Moon Princess. This tale can be retold in numerous ways, including a version from my father, who recounted Kaguya’s journey for me as a child. He had been trying to explain the occasion of witnessing my birth without calling me by another boy’s name. Did he wish for my mother to name me Frederick instead? Did he wish for a minor god? I don’t know. But he had a story about me being born with a little monkey’s tail. The little tail fell off shortly after my earthly entrance, he alleged. Additionally, it was rare to hear me cry as a baby. Things were always falling off of me, I guess.

Lua, then, is she an “alter” personality? Calling back to your gentle concern about the “pathologizing of the polyvocal,” I can see connective tissues forming around a multiplied consciousness, the expansive Borgesian Library of Babel, and the bright hexagonal figure slowly taking shape. But I’m only still with the number four!

Oh, it now occurs to me in further overlapping shapes… Let’s see… If the artist’s work originates from a three-cornered plane, as Natsume Soseki ventured to paint, the written story gains its language through an additional angle, therefore moving toward the square of prose. Thus, ascending or descending toward the six-cornered form inches closer to a circle! Alright, so this hexagon is a ritual form. The pyre! [Laughs.]

FWR: In a LitHub essay, you wrote that you are the child of a parent raised by someone who had been a prisoner of war. I am also, and stories were told frequently about that family history when I was growing up. Of course, what was told, what wasn’t told, what became told differently over time, and the purpose of the telling all evolved and took on new forms as I grew older. It’s a story that, on some level, I think will continually evolve as long as I continue to consider it. I mention this because there are moments in Tetra Nova when the torture of women during the Vietnam War is recreated as performance art. At many points in the novel, it seems like performance is a vehicle for re-storying, if you will, for moving a story in all directions in time. Your characters are simultaneously ancestors and descendants; their stories are told and reimagined. You are also a performer—how do you articulate the relationship between your writing and performance art? Do you think there can be a restorative quality to telling, retelling/performing, and re-performing?

ST: Please let me share the full-hour performance of Tetra Nova, featuring the Roanoke Ballet Theatre. I hope this explains everything.

FWR: The jacket copy for Tetra Nova describes Lua and Emi as “embodied memory traveling across the English language.” How do you understand this concept of embodied memory? It strikes me as an interesting framing of what it means to be a being existing in time—are we all, for better or worse, really embodied memories? What does it mean to live as an embodied memory?

ST: One flaw in my mechanical design, among many flaws, is that I suffer from terrible motion sickness. If it weren’t for this stomach, I would have pursued as a young adult in this incarnation, in addition to studying divine geometry, a career in space travel. Strap me in! Shoot me up! Enjoy this illustrious life.

Alas, here we are… Yes, as you say, for better or for worse, the memory in a bottle rocket travels along a parabolic arc around the planet’s gravitational pull. Do you remember the seven comets passing by that night? I can only remember four. [See: Illustration by an unknown hand. Source: Mawangdui tomb, Hunan Province Museum]

FWR: I would be remiss, I think, if I didn’t offer an opportunity to discuss Panda directly. I often experienced Panda as an opportunity to indulge in some levity, in some whimsy, within this very charged, cerebral hurricane of a novel. I also experienced Panda as a very grounding presence. Who is Panda? (I see Panda also manages your website.) How do you hope readers experience Panda?

ST: Yay! With his consent, here’s a photo of Panda during the early part of his political endeavors. Thank you so much for speaking with us! This was a lot of fun!

[Photo of Panda by Sophia Terazawa]

- Published in Featured Fiction, home, Interview

FEBRUARY MONTHLY: INTERVIEW with CLAIRE HOPPLE

From the first sentence of Claire Hopple’s latest novel, Take It Personally, you know you’re in for a ride—in this specific case, you’re sidecar to Tori, who has just been hired by a mysterious and unnamed entity to trail a famous diarist. Famous locally, at least. What sort of locality produces a “famous diarist”? One whose demonym also includes the nearly equally renowned Bruce, made so for his reputation of operating his leaf blower in the nude, of course. And that’s just the beginning. Take It Personally follows Tori as she follows the diarist, Bianca, determined to discover whether her writings are authentic or a work of fiction. At least, until Tori has to go on a national tour with her rock band, Rhonda & the Sandwich Artists, who are, as Tori explains, right at the cusp of fame. It is a novel as fun as it is tender, filled with characters whose absurdity only makes them more sincere.

Claire Hopple is interviewed by E. Ce Miller.

*

FWR: It seems like much of your work begins with absurd premises. The first line of Take It Personally is, “Unbeknownst to everyone, I am hired to follow a famous diarist.” This quality is what first drew me to your fiction, this sort of unabashed absurdity. But then you drop these lines that are absolutely disarmingly hilarious. You’re such a funny writer—do you think of yourself as a funny writer? What are you doing with humor?

CH: Thank you! That is too kind. I’m not sure I think of myself as a funny writer, or even a writer at all––more like possessed to play with words by this inner, unseen force. But I think humor should be about amusing yourself first and foremost. If other people “get it,” then that’s a bonus, and it means you’re automatically friends.

FWR: In Take It Personally, as well as the story we published last year in Four Way Review, “Fall For It”, many of your characters have this grunge-meets-whimsy quality about them. They seem to have a lot of free time in a way that makes me overly aware of how poorly I use my own free time. They meander. They follow what catches their attention. They are often, if not explicitly aimless, driven by impulses and motivations that I think are inexplicable to anyone but them. They seem incredibly present in their immediate surroundings in a way that feels effortless—I don’t know if any of them would actually think of themselves as present in that modern, Western-mindfulness way; they just are. In all these qualities, your characters feel like they’re of another time—unscheduled, unbeholden to technology. Perhaps a recent time, but one that sort of feels gone forever. Am I perceiving this correctly? Can you talk about what you’re doing with these ideas?

CH: I’ve never really thought about them that way, but I think you’re right. And I think my favorite books, movies, and shows all do that. We’re so compelled to fill our time, to make the most use out of every second, and it just drains us. There’s a concept I heard about recreation being re-creation, as in creating something through leisure in such a way that’s healing to your mind. We could all stand to do that more. Hopefully these characters can be models to us. I know I need that. But reading is an act of slowing down and an act of filling our overstimulated brains; it’s somehow both. So maybe it’s just a little bit dangerous in that sense.

FWR: Are you interested in ideas of reliable versus unreliable narrators, and if so, where does Tori fall on that spectrum? She’s a narrator presenting these very specific and sometimes off-the-wall observations in matter-of-fact ways. I’m thinking of moments like when Tori’s waiting for the diarist’s husband to fall in love with her, as though this is an entirely forgone conclusion, or the sort of conspiratorial paranoia she has around the Neighborhood Watch. She also “breaks that fourth wall” by addressing the reader several times throughout the book. What are we to make of her in terms of how much we can trust her presentation of things? What does she make of herself? Does it matter if we can trust Tori—and by trust, I suppose I mean take her literally, although those aren’t really the same at all? Do you want your readers to?