Perhaps it’s no surprise that the first of Asa Drake’s two debuts, Maybe the Body from Tin Hous...

FEBRUARY INTERVIEW with ASA DRAKE

OCTOBER INTERVIEW with EDWARD SALEM

Edward Salem is a poet who hasn’t lost his sense of humor. “Palestinians,” he shares in our int...

SEPTEMBER INTERVIEW with LIZA HUDOCK

Addiction, death, and loss are everywhere in Liza Hudock’s debut collection, Reveille (released...

SEPTEMBER INTERVIEW with Julia Thacker

Julia Thacker’s debut collection To Wildness was recently awarded the Anthony Hecht prize...

JUNE INTERVIEW WITH STEVEN ESPADA DAWSON

Late to the Search Party is the debut collection of Steven Espada Dawson, exploring the individ...

INTERVIEW WITH Jessie Chaffee

Jessie Chaffee’s debut novel, Florence In Ecstasy (Unnamed Press), was a San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of 2017 and has been published or is forthcoming in Italy, the Czech Republic, Russia, Poland, Turkey, and Romania. She was awarded a Fulbright grant to Italy to complete the novel, during which time she was the writer-in-residence at Florence University of the Arts. Her writing has appeared in Literary Hub, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Slice, and Global City Review, among others. She lives in New York City, where she is an editor at Words Without Borders. Find her at www.JessieChaffee.com and @JessieLChaffee.

Florence In Ecstasy follows Hannah, a young American in Florence who is recovering from an eating disorder that has severely affected her emotional and physical health. Determined to defeat the disorder, Hannah joins a rowing club, propelling her into the vibrant and tight-knit community of Florence. However, Florence’s mystical history and art, particularly as it pertains to the saints –– women who starved themselves in the name of God –– is seductive, triggering in Hannah a desire to return and reclaim her disorder. Throughout the novel, Hannah asks herself the questions we all must eventually ask ourselves: “Who was I?”, “Who am I?”, and, “Who will I become?”

FWR: To begin, I want to ask you about the origin story of the novel. Did you always know you were going to place Hannah’s story in Florence or was it a discovery along the way?

Jessie Chaffee: The origin was really two things. One was that I was in graduate school and I was reading a lot of books about women on the fringes. And around the time when I started this book, I read the full canon of Jean Rhys, and in particular, her book Good Morning, Midnight, which is amazing. Good Morning, Midnight is about a woman who is descending into alcoholism in Paris and her rendering of that mental state –– which is really hard to do, I think, to capture altered states and addiction believably –– and what is really a love affair with alcohol was so powerful. I wanted to know how to do that.

Almost a decade earlier, I’d had an experience with an eating disorder in my early 20’s, which was less extreme than Hannah’s. I hadn’t written about it and hadn’t been able to write about it, but it left me with questions, and questions are always a good place to start a book. I hadn’t seen an eating disorder written about in the same way that I had experienced it and really Jean Rhys’s account of alcoholism came closest.

FWR: That’s interesting that you say that you hadn’t seen eating disorders written about the way you experienced it. So often I feel that eating disorders are written through tropes and act as warning stories. Like, these characters are the consequence of low self-esteem, or women who have experienced major traumas and destroy their bodies as a result. Much of Hannah’s experience with her eating disorder is wrapped up in art. While so much of her experience seems to come from a search for meaning, especially towards the end of the novel, it also comes from this desire for ownership. She describes the disorder as creating, carving, and sculpting. Can you say something about Hannah’s relationship to art and her disorder?

JC: Thank you. That’s a great question. So, her background in the book is in art and it is how she understands the world and sees the world. And one of the reasons that I wanted to set the book in Florence was because I wanted to put this woman in a place where she would be alone, but also not alone. Florence operates like a small town, so inevitably she can’t remain anonymous forever. But also because Florence is full of art and history –– it’s everywhere –– it made sense to me that she would go there looking for answers, so to speak.

In terms of the artistic creation, one of the things that I wanted to capture about the disorder was the high of it. When I began the book, the saints weren’t a part of it. It was in the writing that they emerged. Reading their accounts of ecstasy and about their very sensual, fulfilling, but ultimately painful relationship with God, I found their experiences resonated with somebody who’s caught up in an addiction. To the outside world, of course, it looks like Hannah is simply starving herself and abusing herself. But the reason that the disorder is so hard for her to get out of is because it’s seductive. It gives her a high. Because there is something about it that makes her feel as though she’s creating herself in this really powerful way. So, I think that’s where the connection to art comes in. She feels as if she’s creating herself. And it is not about beauty. It’s not really about how she looks. It’s about what happens internally when she’s in the process of doing that that drives her.

FWR: Yes! I realized that you’re exploring this idea, especially with Hannah and the saints, of erasure as a way to create. Hannah and the saints are making space by erasing what is already there, in order to create. For the saints, it’s more of a spiritual creation. But for Hannah, it’s a kind of knowledge of the self through the erasure of the physical self, which seems both counterintuitive but also so clearly what we’re often doing as artists–– clearing the space to actually create. Even when you’re filling the page, you’re removing the initial space, you’re changing the actual platform. When you’re painting, you remove the color or the absence of color, and sculpture is also a removal of physical parts. Especially in writing, so much of the work is actually erasing so much of what you put on the page in the first place. There is something in Hannah’s experience that rings so true about the agonizing but also amazing experience of being an artist, just creating and erasing, creating and erasing.

JC: Absolutely! And you’re also trying to erase the self. The best writing for me, and the best moments of writing, are when I disappear, when I feel like I’m no longer in it. I think there really is that kind of total self-erasure where you hit whatever it is that you’re reaching for. It doesn’t happen most of the time, but when you get there, it is almost like this ecstatic state. It is, I think, what can make artistic creation addictive and make you come back to it. And in those moments, I feel like I’m really gone.

FWR: And that brings me back to this theme of ownership. There’s a moment in the book where the reader thinks Hannah’s going to be alright, she’s in a relationship, she’s eating, she has a job at this library full of rare books. But then she steals all these old manuscripts of first-hand accounts of women saints’ spiritual ecstasies, and their experiences trigger her addiction, sending her into a downward spiral. While this is happening she starts talking directly about the disorder, and she’s saying that she “loved it,” that she “clung to it,” but also that it was hers. There’s this real desire for ownership, but she also says that she belongs to it. So then, it seems to me, the big question the novel begins to ask is one of ownership, whether it’s ownership of the self, or art, or history, or the body.

JC: Yeah, that’s great. Hannah does repeat throughout the book this idea that whatever this thing was, it was hers. She states directly, “It was mine.” You know, that’s not necessarily said with pride but is said with a recognition that this relationship is so intimate that it is necessarily a part of her. It’s not just something that is being done to her. And she’s also a part of it. That’s the tricky thing about any addiction, I think, that getting out of it is so difficult because you’re not just letting go of the thing but you’re letting go of a part of yourself. You’re letting go of a version of yourself that is yours. With the saints, I was really interested in their desire to erase, both their individual identities, and also their physical selves through starvation, other kinds of self-mortification, or other behaviors to deny the body. Because their purported goal is to totally erase themselves, right? To give themselves over completely to God, to erase their physical bodies, to be fully in the Spirit, to be completely pulled away from all things earthly and all things of the flesh. However, when they’re practicing this extreme behavior, they’re actually creating these very powerful identities that were long-lasting. And so they were creating the exact opposite of erasure. They were creating a legacy for themselves. And I think there’s real ownership in that. I’ve mentioned it in the book, but the fact that there are all these accounts that begin with “I, Angela”, “I, Catherine”, “I, Claire”. That kind of “I-ness” of the saints is really about the legacy they’re creating through the stories they’re telling about their experiences.

FWR: You do such a good job telling their stories through Hannah’s experiences and growing obsession with the saints. But what I found so interesting is that while she, and the saints, are wanting to erase, so much of Hannah’s experience with them, and with Italy, is physical. You’ve got all these relics, and she goes to see Saint Catherine’s head, and she’s got all these old books that she hauls home. And she’s also in Florence, and is physically experiencing Florence, and joining a rowing club. So much of her identity, in Florence, then, is developed through the physical, and through physical intimacy and pleasure with Luca, as well as pain, like the saints. Can you talk a little bit about how the book is looking at the relationship between the physical and visible and the spiritual and intangible?

JC: I think the saints are so fascinating because their descriptions are so physical. Even though, supposedly, it is about erasure, they have these incredible visceral descriptions. They are very much in their bodies. Even the mortification of the self is really about being in the body and the pain inflicted on it. And I think for Hannah, part of the struggle is to come back into her body. I purposefully set the book after she has really lived in the depths of the disorder because I didn’t want to romanticize that. You see glimpses of it because the reader has to understand her experience, but she comes to Florence to live. She’s trying to live and she’s trying to be back in her body, and so I think she comes to a place that really forces her to be present. Her relationship with Luca forces her to be present, too, and to be present in her body, and so does the rowing. You can’t row without a body. You can’t row with a weak body. You can’t do that if you’re starving yourself. So I think the physical ends up being important to her and that ultimately, even though she’s bumping into all of these remnants of the saints and recognizing the power of their ecstasies and also their mortifications and the behaviors they practice to gain their independence, and to gain their voice, that part of her becoming a body again, is rejecting some of that.

FWR: You said you didn’t want to romanticize the actual disorder addiction. I think one of the ways that you achieve that is actually showing not only her wrestling with it but also the physical pain that she’s experiencing. For example, there’s that scene where she runs and shoves saltines down her throat and drinks a bunch of water, but instead of reducing the pain, she becomes more uncomfortable. It’s not that you are giving the reader these grotesque images of it, but it’s just very real. It’s a very real kind of desperation. Also, what I loved is that you don’t give an origin story or blame the disorder on a huge trauma that happened to her. It seems really important that it is just a state of being that Hannah struggles with, in relation to her status as a woman, not only now, but throughout history.

JC: Yeah, it’s an old story.

FWR: Totally! And you seem to be hitting on a larger societal ill in relation to feminine subjugation. Could you talk a little bit more about what you were thinking as you were developing Hannah’s addiction, but also her intellectual experience of it, because the reader is so much in her head.

JC: A lot of what she’s trying to figure out in the book is: why did this happen to me and where did it start? Thinking about structures and things that you get rid of in books further along, when I started the book, any flashbacks where distinctly set off in italics, and they all began with the line: “This is where it starts.” And it was all sort of an indicator of her searching for the origin of how she ended up in this place where she really lost herself. I appreciate that you say that I don’t give an origin story because I didn’t want there to be an easy answer for “this is why this happens.” And I think that makes some people uncomfortable. I’ve certainly had people ask me, “Why did it happen to Hannah?” And I don’t know if you would get that question when it comes to other addictions, right? Why does somebody become an alcoholic? I mean, you start engaging in a behavior that becomes addictive. Certainly with not eating, there’s this initial positive response. There are so many women of all ages who are at war with their bodies and have negative relationships with food. Hannah is on one extreme end of an eating disorder, but when you think about the spectrum of people’s relationship with food and their bodies, women and men have really disordered behavior all the time. I didn’t want to give a single reason for why this is happening. Also, I was less interested in the reason that it was happening than why somebody would get caught up in it, and what would make it hard for them to get out of it. I also was hoping that people reading the book would be able to relate to it so that whatever kind of addiction or abusive relationship anyone has experienced, they might be able to find some of that in Hannah, rather than saying, well, I didn’t experience this trauma so I don’t relate to this.

FWR: I don’t think you need to have experienced a major trauma or addiction to be able to connect with Hannah. She’s simply struggling between the desire for control and the desire to let go, which is innately human. Yes, Hannah is an extreme version of that, especially in today’s world. But these desires were also experienced by the women saints. Their ecstasies are about control and fulfillment, right? And meaning. So many of the saints’ lives are interpreted historically as a way to escape a strict patriarchal system that limited their agency. Saint Catherine didn’t want to get married. Saint Bernadette also wanted to avoid being forced into a relationship with a man, and so many other female saints experienced ecstasies or visions in order to remove themselves from the society that wanted to control them. But they also wanted to remove the feminine connected with that society, maybe perhaps in order to have control over their own selves. And with Hannah, she has this conversation with Luca about not eating, and Luca asks her if it’s because she wants to be skinny, as if it has to do with being sexy or attractive, and she immediately rejects this idea. And it reminds me of all these conversations I’ve had with friends and essays I’ve read about wanting to hide the body, to avoid being seen as sexy and feminine, and instead attempting to hide the self through baggy clothes, or boyish looks, or anything that might help make the feminine part of the body disappear.

JC: Right. Wanting to not go into the world body first, which is what happens for girls as soon as they hit adolescence. Your body is no longer yours once it begins to be seen and noticed. Throughout the book, Hannah has this sense that she’s being watched all the time. There is this desire in her to disappear, which in a certain sense is a removal of the feminine. But that ultimately isolates her and her ability to connect intimately with other people. And I do think a part of her actions throughout the novel are about wanting to disappear. The disorder is certainly not about her wanting to be beautiful, but it’s about something different. Part of that does become about erasing herself. But part of it too, and this is the hard thing about any addiction, is that it starts as one thing, and then it becomes something else. So it begins as maybe a control, or self-erasure, or the desire for something that she hasn’t found, and it becomes a place of meaning. You know, it becomes a kind of philosophy. It’s great to find meaning and it’s great to find your philosophy if it’s in a place that’s healthy, but often we find those things in places that are unhealthy and that makes it really hard.

FWR: One of the things I think the book is doing so well is that it makes some really interesting statements about what it means to form identity, and what are the consequences and risks of claiming, creating, or denying identity. And so much of Hannah’s eventual reclaiming of her identity is dealing with those consequences. She goes to Florence, she starts rowing, she becomes romantically involved with a man, and so much of the trajectory could just move towards this idea of the runaway love affair that will save her, but then you take an entirely different turn. And, without giving too much away, so much of Hannah’s reckoning with her own identity is dealing with the world she’s run away from.

JC: Much of that was very conscious. Many of my favorite books are incredibly dark, where things don’t end well. And I didn’t want to write a book that had this easy, unrealistic, happy ending, but because I was writing about something that I’ve experienced and I know a lot of people experience, I didn’t feel like I could leave the book in a totally dark place. There had to be some hope. I feel hopeful for Hannah and her ability to not necessarily get out of things, but to live with things and survive. It’s not something that can be answered and fixed by somebody else loving and accepting her. So, I always felt like she had to go home because part of actually taking ownership of her life is dealing with her life. Part of being an agent in her life is facing it and dealing with it. That doesn’t mean her relationship with Italy and with Luca isn’t meaningful. It is meaningful. But just because it’s meaningful doesn’t mean it’s the answer.

An excerpt from Florence In Ecstasy

I wake the next morning to rain that doesn’t let up. At the club, everyone will be indoors—all bodies crowding in, all sounds echoing loud, all the older men clustered in the bar instead of on the embankment, all eyes and voices. I avoid it. I should open my laptop, look for work, but I avoid that, too.

I visit San Frediano in Cestello on the other side of the river, the Oltrarno. Luca was right—the church is beautiful. A small plaque on the wall outside announces that the mystic, Santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi, lived and died in the adjacent convent. Inside, there is a chapel dedicated to her with a painting of the saint in ecstasy, and in the chapel’s belled ceiling she welcomes souls into Heaven with sweeping arms. This is why he sent me here. There is nothing more, though—not in the little brochure I was handed and not in my guidebook—and the gates leading to the convent beside the church are locked.

I find a small café not far from the church, glowing warm on this gray day. I stop for a coffee, but the place seeps in, holds me there, and I stay from early afternoon into evening, alternately reading and watching people battle the rain through the wide window. I return the next day and the day after that. The waitstaff has no qualms about my making the transition from a coffee and salad to a glass of wine when the café empties and they have their staff dinner, scraping at plates and laughing, while I watch the gray light stretch across the tables in shifting bands and catch in my glass.

I’m still reading about St. Catherine. As a teenager, she pleaded to join the Mantellate, a group of older widows cloistered in the Basilica of San Domenico, but her parents refused—she was not old and was not a widow. She would be married. Until she grew ill, so ill that even when her father took her to the thermals baths, the boiling waters had no effect. Her illness was a sign from God, she said, and so her parents acquiesced, allowing her to join the widows in prayer, and Catherine was healed.

Her career began with a movement inward, with visions and ecstasies. When in a trance, she did not wince at the needles that disbelievers jabbed into her feet. This and her vision of a mystical marriage to Christ secured her celebrity. As she grew older, she looked outward beyond San Domenico. She cured the lame, drew poison, and drank pus from the sores of the sick. She learned to read and became politically active, composing letters of criticism to the pope.

And she made herself empty for prayer. By age eight, she was slipping meat onto her brother’s plate. By sixteen, she ate only fruits and vegetables, then used instruments—a stalk of fennel, a quill—to throw them back up.

As another steaming dish arrives nearby, the thick, smoky smell drifting my way, my stomach turns over—with desire, then revulsion—and in this, I understand the saint’s denial. I remember well when my days became punctuated by sharp sensations:

Chills.

Sunlight too bright.

Sounds attacking.

Counting. And with the counting came praise and with the praise came questions. How do you do it? Claudia asked, one of a chorus when I began losing flesh, December into January into February. There was admiration in their voices, and I knew what they were asking: How do you cut so close to the bone? By the time Catherine joined the Mantellate, she had stopped eating almost entirely. This body of mine remains without any food, without even a drop of water: in such sweet physical tortures as I never at any time endured. She was empty, open. I’d like to think that she belonged to no one but herself, that the sweetness of the pain was hers alone. But she writes, My body is Yours.

Love. Her letters are filled with the word. The soul cannot live without loving… The soul always unites itself with that which it loves, and is transformed by it. I envy her ecstasies, emptied of everything. Is that love? All that emptiness and the trance that follows? Love is a tunneling, I think. An envisioning and then a tunneling of vision, the edges disappearing until all that remains is the beloved. I had hoped that I would feel that with Julian, that with him I might escape the mornings when I woke tamped down and pressed myself back into dreams that did not soothe. But he was no match for the other solace I found. He fell away with all the rest.

By the second day of my residency at the café I’m almost all the way through Catherine’s life. The soul is always sorrowful, she writes, and cannot endure itself. Outside, people are hurrying through the rain to the evening service. The bells begin to clang furiously, ricocheting off one another as one of the staff appears.

“Un altro bicchiere?” he asks, lifting my glass.

“Sì,” I say, wanting him to leave me to listen to the bells. They are playing a hymn. It is familiar to me and I feel a rush of happiness, uninterrupted. Even in this gray light it grows, and I’m afraid of the moment when I’ll slip over the peak and feel it dissipate. I close my eyes and the bells continue. They are asking a question: Are you searching for? Are you searching for?

SEPTEMBER INTERVIEW with Julia Thacker

Julia Thacker’s debut collection To Wildness was recently awarded the Anthony Hecht prize...

FEBRUARY MONTHLY: INTERVIEW with CLAIRE HOPPLE

From the first sentence of Claire Hopple’s latest novel, Take It Personally, you know you’re in...

JUNE MONTHLY: In Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Nearly a year after the October 7 Hamas terrorist attack and Israel’s subsequent escalati...

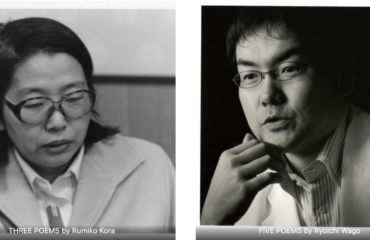

ECOPOETRY FROM JAPAN with Ryoichi Wago and Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION by Judy Halebsky THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebs...

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi FIVE POEMS by Ryoichi Wa...