Take Four: An Interview with Paul Lisicky

In the first installment of our new interview series, “Take Four,” we talk to contributor Paul Lisicky about his short story “Lent” and his latest collection from Four Way Books. In between issues, we’ll keep the conversation going as more contributors share their thoughts on recent work, current projects and the challenges of writing well.

FWR: As one might expect in a story called “Lent,” there are a number of references to abstention, and to the intentions that motivate its practice. In this way the story reveals an interesting tension between spirituality and modern life. Do you think that anyone still knows how to abstain, or is abstinence no longer considered a virtue?

PL: That’s a great question. Father Jed, the central character in that story, certainly tosses around some ideas about abstention, but I think his thoughts probably have less to do with virtue than they do with some kind of personal crisis. He’s so concerned with correct appearances (i.e., Father Ben’s mismatched shoes) that he completely misses the fact that the guy is levitating. I actually think the story is pretty much on the side of permissiveness when it comes to spiritual matters, even though Father Jed is the lens of it. I sort of expect the reader to identify with the people in the assembly, who might be doing just fine with their liturgical dancers and folk hymns.

It would be interesting to write a story that seriously considered the abstention question. Most of my books have been about desire, the paradox at the center of it – how it sustains us as it ruins us – but not so much about pure refusal. It seems to me that many people around us are in the practice of abstaining from one thing or another all the time – think about AA or NA or SAA and how entrenched those programs are in urban life – but maybe that’s another matter. Abstention is different if you don’t already have a problem with excess. But how can anyone not be in some difficult relationship with excess in a culture that encourages so much wanting?

FWR: It’s interesting that you say most of your books are about desire. It’s obviously an important aspect of fiction. Kurt Vonnegut famously said, “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” But in good fiction it’s usually more complicated than that. Perhaps what’s missing from a story in which someone simply wants a glass of water is this tension you’ve mentioned, between desire’s power to sustain and its power to ruin. Would you agree? And would you say that much of your own work begins, conceptually, with this tension in mind? Or does it more often evolve naturally from character?

PL: I’d definitely agree – desire is always a two-headed beast, and I’m not even interested in pursuing a story until I can find my way into its opposing energies. Usually a story doesn’t start with character for me, but from situation or image. Right now, I’m writing a little story about a toll taker on a highway, a woman who leaves her corporate job behind to pursue a childhood dream. The tone of it is tongue-in-cheek and not. I just know I wouldn’t be able to write the story unless I were focusing on the image of the tight space my character has to occupy as the cars are aiming at the toll booth at high speed. So a story for me starts with the metaphor, and the metaphor has to be in sync with sound – by that I usually mean an opening sentence with a particular cadence. Once I have those two things in line, a character can emerge. I can’t imagine working from character alone – human beings can be so inscrutable, all over the place – but then again I’ve never exactly been a realist.

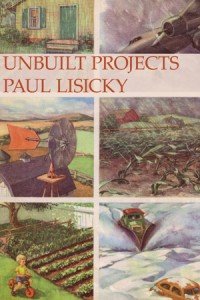

FWR: Religion seems to be another common theme in your work, though it often functions as a lens rather than the object itself. For example, “This is the Day,” a story from your new collection, Unbuilt Projects, presents Christian mythology as a kind of philosophical system, which the narrator uses to interpret an emotionally painful reality.

PL: It’s funny you should be asking this now, as I’ve been going through the last draft of a new memoir, and I was just telling myself to “get rid of this holy stuff!” By holy stuff, I’m not so much talking about thinking, but a borrowed pitch or tone that presumes the reader’s going to hear it and align with it. I can’t stand coming upon that, and my bullshit detector has been razor sharp about it these days.

I’m a big fan of people like Noelle Kocot, Joy Williams and Marie Howe, who are all pretty open about the subject of God – or they’re at least asking questions about God in their work. Marie is a good friend, and I was actually reading The Kingdom of Ordinary Time in manuscript as I was writing the first pieces of Unbuilt Projects. Marie’s book pretty boldly riffs on scriptural narratives, and I took direction from it. She’s not writing didatic work; she’s, as you say, using the mythology as a philosophical system.

I think there’s a lot of anger and bewilderment about God – or around the subject of God – in Unbuilt Projects. That wasn’t made up. The structures that I’d grown up with, the system that had sustained me, even though I wasn’t always aware of it as an adult – were shattered for a time by my mom’s confrontation with dementia. You can hear lots of anger in “How’s Florida?” and “In the Unlikely Event” and “Irreverence.” But I’m glad the book also has pieces like “The Didache,” so that the implied question – ”What kind of God would allow this to happen to someone who matters to me?” – has another side. I wouldn’t want that question to simply generate rage. Rage isn’t the whole story, it never is.

FWR: It sounds like the stories in the book were at least partly cathartic. Of course most literary fiction is written for the author’s benefit as well as for the reader’s, but in some cases this seems more so than in others. This more personal work must come with its own unique difficulties. Do you have any advice for writers who find themselves staring down similar projects?

PL: My favorite stories and novels always have a sense of necessity about them. They feel impelled. It’s hard to say exactly what “impelled” is, but we feel it when we’re reading it. Maybe we could say that the work has come into being out of the writer’s suffering. Maybe it digs into the why? of the situation – which is unanswerable, finally. It doesn’t feel like the writer has even chosen to write such material. It’s chosen him or her – maybe.

I think if you can choose whether or not to write a difficult personal experience, then maybe you shouldn’t write it. Or not write it directly, at least. Find another narrative (or set of metaphors) in which to plant that energy. Mere transcription is never enough anyway. It always has to be about craft, distinctiveness of expression. Exactness of pitch and pacing. The sentences.

Catharsis is a funny thing. I’ve been reading Joy Williams’ 99 Stories of God and I keep thinking about this passage:

“Franz Kafka once called his writing a form of prayer.

He also reprimanded the long-suffering Felice Bauer in a letter: ‘I did not say that writing ought to make everything clearer, but instead makes everything worse; what I said was that writing makes everything clearer and worse.’”

The slyness of that passage might not be available out of context, but I completely get what it’s suggesting. I didn’t feel lighter or wiser or stronger after finishing Unbuilt Projects or The Narrow Door, the new memoir. I might have in fact felt “worse” afterward – who knows? I kicked a lot of questions around, questions that felt necessary to give form to. That’s the most of what we can expect of the things we make, at least on the personal level. We’re lucky to have tools that can possess us completely (in our case, language) when the people and places we love might be falling down around us. Frankly, I don’t know how anyone thrives, much less endures, without having sentences or musical phrases or paint or whatnot at their disposal. That’s the biggest mystery to me. I want to know how those people do it.

|

|

|

More Interviews |

RADIO TRANSMISSIONS IN MORSE CODE (m+39) by P.J. Williams

m+39

] noise [

…– —– / ….. ….. / ..— —.. .-.-.- .—- -…. …– ….- /

-. –..– / —.. ….. / ….- ….- /

.—- —-. .-.-.- —-. —.. .—- —.. / .–

.. .—-. — / – .-. -.– .. -. –. / – — / … .-

-.– / …. . .-.. .-.. / .. … / ..- -. – .. . -.. /

] noise [

. — .–. – -.– / — -.– / … – — — .- -.-. …. /

.- –. .- .. -. / .- / -.-. .- .-. -.-. .- … … /

.. -. / .–. .-.. .- -.-. . / — ..-. /

] noise [

.–. .-. .- -.– . .-. / . .- -.-. …. /

-. . .– / ..-. .. .-. . / .. … /

… .- .-.. – / . .- -.-. …. / .-. .- .. … . -.. /

.–. .- .-.. — / .- /

] noise [

… ..- -. / -.. .. .- .-.. / -… ..- – / … – .. .-.. .-.. /

– …. . … . / .– — .-. -.. … / .- -. /

.- – – . — .–. – / – — / … .–. . .- -.- /

] noise [

… — ..-. – .-.. -.– / – …. . / – .. .-.. – .. -. –. /

–.. . -. .. – ….

] noise [

[end]

Origin: 30° 55′ 28.1634” N, 85° 44′ 19.9818” W

I’m trying to say

Hell is untied & empty /

My stomach again

a carcass in place

of prayer / Each new fire is salt /

each raised palm a sun

dial / But still these words

an attempt to speak softly /

the tilting zenith /

or

Back to Table of Contents

RADIO TRANSMISSIONS IN MORSE CODE (m+11) by P.J. Williams

m+11

…– ….- / …– —– / …– ….- .-.-.- ….. ….. ..— ..— /

-. –..– / —.. —.. / ….- ….. /

..— —– .-.-.- ..— .—- ….- / .–

…. — .– / — .- -. -.– / — .. .-.. .-.. .. — -. … /

…. . .- -.. … .– — .-.. .-.. . -. /

… .. -. -.- .. -. –. / … — /

] noise [

… — — -. / .- … .-.. . . .–. / …. — .– /

.-.. — … … / .. … / – — -. –. ..- . -.. /

-. — / -. — /

…. . .—-. … / –. — -. . / .– . .- -.- -. . … … /

] noise [

.. -. / — — ..- -. – .- .. -. / .– .. -. -.. … /

.– .- .. … – / -.. . . .–. /

.. -. / — — ..- -. – .- .. -. /

.– .. -. -.. … / …. .- .-. .–. /

.– .-. . -. -.-. …. . -.. /

] noise [

… .. .-.. . -. – / — — — -. / – — .-. –.- ..- . -.. /

-.. — .– -. / – .. –. …. – / ..-. ..- .-.. .-.. /

.–. .-.. .- … – . .-. /

— …- . .-. / .- -. / . -.– . .-.. .. -..

] noise [

[end]

Origin: 34° 30′ 34.5522” N, 88° 45′ 20.214” W

How many millions

headswollen / sinking / so soon

asleep / How loss is

tongued / no / no / he’s gone /

Weakness in mountain winds / Waist

/ deep in mountain winds /

Harp wrenched silent / Moon

torqued down tight & full / plaster

over an eyelid /

or

Back to Table of Contents

RADIO TRANSMISSIONS IN MORSE CODE (m+3) by P.J. Williams

m+3

…– —-. / ..— ….. / .—- .-.-.- —-. —-. ..— /

-. –..– / —.. ….- /

….. ….. / ….- —– .-.-.- —– —– –… ….- / .–

…. .- …- . /

..-. — ..- -. -.. / … …. . .-.. – . .-. /

.. -. / –.- ..- . … – .. — -. … /

] noise [

.- – / – …. . / -.-. .-. — … … /

— ..-. / – — -. –. ..- . … /

.–. .-. — .–. …. . – … / …. .. … … .. -. –. /

] noise [

— ..- – / .- -. — – …. . .-. /

… …. .- .-.. .-.. — .– / — — -. … – . .-. /

— -.– / — .– -. / ..-. .-.. .- – – . -. . -.. /

— — ..- – …. /

— -.– / …. — ..- .-. … /

— ..-. / … .. .-.. . -. – / … .–. . . -.-. …. .-.. . … … /

.. ..-. / .. – / … …. — ..- .-.. -.. /

– …. ..- -. -.. . .-. / .. ..-. / .. / .– .- … /

– …. . / — .- -. / .. -. / – …. . /

.– .- -. .. -. –. / — — — -.

] noise [

[end]

Origin: 39° 25′ 1.992” N, 84° 55′ 40.0074” W

Have found shelter in

questions / at the cross of tongues /

prophets hissing out

another shallow

monster / My own flattened mouth /

my hours of silent

speechless / If it should

thunder / If I was the man

in the waning moon /

or

Back to Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION TO RADIO TRANSMISSIONS IN MORSE CODE by P.J. Williams

“These poems are from a larger project called Zero Sum, and they come from a section of the manuscript in which the speaker survives a cataclysmic event. Over the days and weeks following, he overhears on his radio these Morse code transmissions in between the interference and static. He translates them as best he can and organizes them into poems.

I don’t want to over-explain them because they rely a little on the unknown as something that would be characteristic of the post-apocalyptic world, but there are a few things that may be helpful to know. The first is that each stanza is a haiku. I chose that form because it is so old and the project is concerned with what survives over time—and often times what doesn’t—and also because the form makes me think about language in a way that also seems appropriate for the world in which they are written (a spare, barren sort of language).

The titles—“m+3” and “m+11” and so on—tie back to the name of the event that brings the world to an end. The event is called The Miranda. Miranda is the character in The Tempest who has the famous “brave new world” line, and the poems themselves actually started with language borrowed from The Tempest; but, they’ve gone through so many revisions now and put into this form that that may not be recognizable anymore.

Everything else I sort of want to leave up to you to experience how you will experience. Obviously you are free to google the GPS coordinates and find out where those transmissions are coming from. Those locations were chosen for a reason, but I sort of want that reason to be open for interpretation.

Thank you to Four Way Review for publishing these and working with me on pairing the sound clips of the Morse code transmissions coming through with the poems themselves. I think that’s a really exciting way to experience the work.

I’m really honored to be a part of this issue. I hope you enjoy.”

Begin the series by clicking here…

or

Back to Table of Contents

MAP (7) by Ye Chun

7. Olympia, Washington

The Pacific Ocean shovels coals in the distance.

My drunk friends drop pebbles at me as I lie

on the couch losing water. Be happy, be happy, be happy.

I’m trying to see spring sprout, mountain that smells like green apple,

grass younger than me, to see the pink sweater

I wore when the sun sprinkled pink dust and I practiced

xiang gong to make my body fragrant,

not the speeding lines of the steel tunnel,

a hand gridding its fingers on my ribs.

I’m trying to breathe, to reach water or an address.

In the white house

with white windows

who spends the night?

The dead say: don’t

talk so loud

I can hear you

even before the words are said

In the woods

there is a bird

whose feathers

have every color

in the world

You’ve seen it

You’ve gathered

every name of it

in your throat

MAP (5) by Ye Chun

5. Lhasa

Seeds tier in a pomegranate.

Sweat beads convex-mirror corners of a night.

You pick up a piece of coal from roadside,

wrap it in a blue and green checked handkerchief

and give it to me: What makes you feel warm?

In the Himalayas, a snow leopard

spins gold in early morning. I tie a prayer flag

to a balloon and let go. Its little feet step through clouds

and rain falls on the white stupas, the hind-scalps

of prostrating pilgrims who say: om mani padme hum, om

mani padme hum, om mani padme hum…

Buddhakapala

(Skullcup of Buddha)

presides over

twenty-five deities

two hands

holding his consort

(Citrasena)

four hands

his skullcup

chopper

ceremonial staff

and drum

In the dancer’s pose

(ardhaparyanka)

he stands on a corpse

supported by a lotus

MAP (4) by Ye Chun

4. Shenzhen

Streetlamps imitate stars.

Stains on a hotel ceiling imitate mountains, boats and ruins.

…either do great good or great evil,

the journalist, 23, says. We walk

along the low brick wall into a park. A palm tree

stops us and deepens the ocher of our faces.

A stone bridge shapes an ellipse with its shadow. We

don’t have much to do so we press each other’s body.

Is a compass a moon bringing a finger to its lips?

A mosquito net

with a crimson mosquito

A roach crawls beneath the net

onto her right leg

My leg feels odd

she says

It’s broken

her algebra teacher says

It’s broken

her chief-editor says

It’s broken

the legless beggar says

It’s broken

the manager of Human Resources says

It’s broken

her snoring lover says

On the wall a map

of cherries and water paths

MAP (3) by Ye Chun

3. Zhongzhou, Luoyang

This area is between brown and purple.

All the apartment buildings look the same.

I need to lie down, call out

your name to one of the black-barred

windows. In the most crowded market,

my classmate is selling embroidered pillowcases and lingerie.

If you appear, I’ll make you look at me balancing

the sick little invisible animal

on my head. I love the sweet numbness of dusk—

we glow before vanishing.

Lay out the grid

of roads and wards:

Align the northern part

of the western wall

the middle stretch

of the eastern wall

and a road that comes

in Gate VII

turns west

and heads south

nearly reaching

the course of the Luo

Align the other roads

the southern part

of the western wall

most of the northern stretch

and the surviving part

at the southern end

of the eastern wall

MAP (1) by Ye Chun

1.Niujie, Beijing

When the earth shakes, hunching grandma

picks me up, cousin’s uneven leg shadow-puppets

the window. The sky lowers like father’s raincoat

till the old lady carried out by her son

drums on his head: Let me die at home, let me die.

We live in a tent, eat government bread

and play on a monkey-hill. The world stays

a cotton ball in big sister’s bleeding nose.

Worms swim in my belly, warm air rubs my soles.

“The image of spider web and cocoons in ‘Niujie, Bejing’ came

from Napoleon’s Collection, painted by Elizabeth Schoyer, whom

I studied with at the University of Virginia. In fact, the poem

sequence grew out of an art exercise for her class. For the exercise,

we made a map of the place we grew up. In the sequence, each

poem is a place and consists of two stanzas — the one on the left

pockets traces of experience; the one on the right serves as sort of

notes on the experience. Together they work like lines of latitude

and longitude to locate the experience.”-Ye Chun

Draw a spider web

with small cocoons

Draw one cocoon

of hymenoptera

one of polyp

of cynodont

one with a man inside

the man with a bird

in his belly

(its singing is its gyration)

with a bomb in his head

(its ticking its nutrition)

Ye Chun’s “MAP”, continued…

“This is meant to be the story of all lives, though I’m talking about one in particular,” Lisicky writes, and if the goal of Unbuilt Projects is “to be the story of all lives,” Lisicky has succeeded. Adept at harnessing the highs of life that are ruthlessly countered by lows— “see how the plants grow. And die a little”—these pieces are anchored by truths and by Truth. With an aptitude for creating vivid scenes, Lisicky envelops us in his stories, so though we did not stand under “The sky so scrubbed with stars it hurts,” it is as if we did.

“This is meant to be the story of all lives, though I’m talking about one in particular,” Lisicky writes, and if the goal of Unbuilt Projects is “to be the story of all lives,” Lisicky has succeeded. Adept at harnessing the highs of life that are ruthlessly countered by lows— “see how the plants grow. And die a little”—these pieces are anchored by truths and by Truth. With an aptitude for creating vivid scenes, Lisicky envelops us in his stories, so though we did not stand under “The sky so scrubbed with stars it hurts,” it is as if we did.