THESE SISTERS by Anthony Varallo

These sisters, both teenagers, share a bedroom. The bedroom is too small for them to share, a fact that’s become clearer the past year or so, but one that won’t fully be understood until later, when they’ve both moved away from the house and graduated into adulthood, where they can recall the way the bedroom felt on those warm summer nights when they had the windows open, no breeze coming through while an oscillating fan turned at the foot of their beds bringing relief and then dismay in alternating intervals. The bedroom’s walls seem too close. The bedroom door, open to admit the family cat, makes faint creaking noises, the source of which is never understood. The cat sleeps heavily upon one bed or the other.

Often, these sisters wake in the night. Say the cat hops off one bed or onto the other bed. Say a car passes outside, its headlights sending long parallelograms across the bedroom’s walls. Say it rains. Or, more often, these sisters wake for no reason whatsoever, save the inability to turn off the movie in their heads, the one that plays happily throughout the daytime to let these sisters know they are loved, cared for, admired, even, versus the one that plays at night, where these sisters’ fears, doubts, and worries are the sudden stars.

The fact is, these sisters make noises at night. These sisters expel gas without the usual discretion. These sisters toss and turn. These sisters snore. These sisters alternately blame each other in the years that follow for being the noisy one.

You wouldn’t stop snoring! one sister claims.

That was you! the other says.

You always got up to use the bathroom.

What? That was you! And you always left the bathroom light on.

I was the one who had to turn it off!

No, that was me.

The middle of the night: one sister rises from bed, touches her feet to the floor. In the other bed, the other sister snores. She turns to face the wall. The beds, twin-sized, hug opposite sides of the room to give a suggestion of space, of privacy—but it isn’t enough. One sister tiptoes to the bathroom (these sisters know all the creaky spots on the floor, even in darkness) and turns the bathroom light on, then shuts the door to keep the light out. She flushes the toilet, washes her hands in the too-cold water that lurches from the bathroom faucet. Her eyes are open, but not really, either. She turns the bathroom light off, opens the bathroom door. The room is quiet, except for the fan, turning its head toward a bed, the cat, the other sister.

And here is the thing both sisters forget, years later, a part of the memory that slips past their recollection: the moment when, eyes not yet adjusted to the dark, one sister stands in the bathroom doorway, planning her path back to bed and wonders, briefly, Now, which sister am I?

- Published in Issue 18

KORREBRUG KAFKA by Stefani Nellen

When I was still training for marathons, I tried to run a 30 km loop from Groningen to Bedum and back. I got lost and ended up in Beijum, a neighborhood built in the Seventies, with streets folding into each other like lobes of a brain. By then it was getting dark, and the skies opened up. Within seconds I was wet to the skin. More by accident than design I made it to a recreation area with artificial hills, and trails with precisely the right degree of ruggedness.

My sons have never been athletic, with their pointed faces and cunning smiles, with their saucer-eyes and coal-black hair. They looked and acted like twins, even though they were born almost two years apart, both of them born victims of the kind of boy who dominated the fake wilderness of suburban parks. My sons came home from the playground with smashed glasses and spit in their hair. Once I said to them: “Hit them back if you have to. Once is enough, if you do it right. Do you want me to show you how? Do you want me to treat you like young men, or do you want me to treat you like porcelain dolls?”

The younger one said, “Like porcelain dolls?”

If he’d said it with the languid impertinence of puberty, I’d have been thrilled. But no, he sounded hopeful.

My husband said I was too hard on them. Every evening after work, he’d coax them into a game of soccer, as if to prove to me how strong and robust they actually were. Each of our sons’ stumbles or half-assed kicks-past-the-ball made it clear to me that they only played for his sake. They didn’t do anything without transmitting the same silent commentary: Whatever it looks like we are doing: we’re not really doing it. We only pretend.

My younger son killed himself when he was nineteen. People assume that, as the mother, it’s hardest on me. That may be so, but I worry about my oldest. He was his brother’s best friend, and despite his privileged access to the black diamond piste of the little one’s soul, he couldn’t save him. In the public eye his failure isn’t half as enormous as mine, but I fear he disagrees.

*

A man passed me on his bike. He was tall and thin and wore a long overcoat. A wooden box was attached to the handlebars of his bike.

“Excuse me?” I called.

He stopped very gradually, and I walked after him. It took me a long time to catch up. We stood under a yellow streetlight shaped like two eggs on top of each other. In the yellow, grainy light I saw he was Kafka, Franz, the insurance lawyer and nighttime writer specializing in gatekeepers. He stood there steadying the bike, which looked old and delicate between his long legs, and appeared to be unwilling to stop, yet forced to do so by his manners and upbringing, and embarrassed on my behalf for bringing about a situation the consequences of which I could not possibly fathom. I asked him for the quickest way to the Korrebrug, the bridge that would bring me back into the city.

“That’s not going to be easy,” he said with an apologetic smile. “Let me try to explain.” Something was scratching against the inside walls of the box. Kafka started to describe a route that would be impossible to memorize, a route past the hills and around the lake and through hidden streets, a route filled with turns you were guaranteed to miss, and even if you didn’t you would probably get lost. You really had no chance of making it. It was scandalous. Local kids stole the road signs to confuse strangers.

Kafka used one hand to draw the map in the air, but soon he shook his head and laughed. “No, no. It’s impossible to explain.”

“So it’s this way?” I said, pointing where I thought I saw the aura of city lights.

“Yes. Maybe. But the honest answer? Is no.”

“Thanks, anyway. I’ll keep trying.” Standing still, the muscles in my legs had stiffened. Once I started running, my legs felt like fat candlesticks I had to drag along. Kafka cycled next to me, pushing the pedals each time his bike was about to topple over.

“It’s not the Korrebrug, by the way,” he said. He looked uncomfortable, as if he would have preferred to keep this fact to himself. “The bridge you’re looking for is actually called the Gerrit Król Brug. There’s a sign right next to it. It’s too heavy to steal.”

“I’ll try to remember.”

“Where do you live?”

I told him.

“I could give you a ride on my bike.” A questioning screech sounded from the box, and he said, “We would need to hurry.”

“What’s in the box?”

He clicked his tongue. “That’s really none of your business. Hop on.”

I sat down on the back of his bike, and he started pedaling. The bike’s chain creaked, and his long, narrow back moved in the rhythm of his legs. With every turn of the pedals, my life was pulled further away from me. My house, my husband, the potato dinner waiting for me in the oven, the nights when I couldn’t sleep: all fading.

And at the same time, another strange thing happened: it was as if his bike became a machine that was slowly pumping the years of my life out of my body, emptying it of grief and motherhood and returning it to my girlhood shape. If I looked down, I would see a girl’s legs dangling down one side of the bike, a wet skirt covering my thighs, sandals on my feet. How long could this continue? Would I change into a baby? Would Kafka place me in the box and take me home, to keep him company? Or would he keep cycling and obliterate me completely? Had he taken my younger son this way?

Kafka’s coat was thin, his body warm against my mine. I closed my eyes and saw the pointed faces of my children. The older walking the younger to his first day of school. Their flopping walk. I wrapped my arms around Kafka’s middle and held on tight. When I stuck out my tongue, I tasted the rain running down his coat.

“Here it is,” he said.

The Korrebrug is a drawbridge across the canal. It’s open most of the time. Cars spend more time waiting for it to close than crossing it, but the arches to the left and the right of the main bridge are high enough for the ships to pass underneath, and on these arches are stairs and metal grooves for cyclists to push up their bikes. Kafka did not ask me to get off his bike, however; he biked up the bridge inside the metal groove, which should have been impossible. We gained traction. Something was sliding inside the box and made a keening sound.

For a long time, it felt as if we were almost on top of the bridge, but the distance didn’t change. Kafka kept pedaling. A cargo ship approached, low in the water, heavy with black mounds of powder. I read the letters on its side, shortened by perspective. Menorah.

I held on to Kafka as if I were his backpack, my lips sliding against his back while I talked. “I better confess,” I said. “I never read your books, except one.”

“I’m not surprised.”

“We read The Metamorphosis in school. I love how Gregor’s sister keeps bringing him food. Human food at first, and when she understands he can’t bite and chew and digest this food the way humans can, she feeds him things an insect would like. She doesn’t berate him for having the wrong kind of mouth.”

The Menorah’s engines roared as she passed the under the bridge. Waves slapped against the quay. The arch underneath us shook.

“I always wanted to read Letter to Father,” I said. “Nowadays, you have books called Letters to My Children. But no one reads them, except other parents.”

We made it to the top of the bridge. Kafka slowed the bike; I felt for the ground. As soon as the tips of my running shoes touched the ground, my body changed back into its present shape in my perception, the weight and memory back in every cell. I dismounted. He leaned his bike against the rail and coughed, holding on to the handlebars. He coughed for a long time. “Sorry. I’m out of shape.”

My shoes were soaked, and my clothes stuck to me like a second skin. The black band of water was still moving in the wake of the ship.

“Let’s stay here for a bit,” I said.

“No way. It’s freezing.”

“I’m not cold.”

“Look. It’s been a long day, and all I wanted was to ride home from work and watch a movie with my girlfriend. And now this happened. Get back on my bike, lady, and I’ll take you home.”

“I don’t want my life to continue.”

“Great.” Another keening crept from the box. “Well, make up your mind. You hear what I have to put up with.”

My phone rang. I carried it in a waterproof pocket at the lower back of my shirt. While I contorted my arms and torso to unzip the pocket, Kafka opened the box and whispered to the thing inside. My phone was warm. The display said HOME.

Without turning away from the box, he said, “Take the call.”

I picked up, expecting to hear my husband’s voice, but it was my older son.

“Where are you?” he said.

“I’m on a bridge.”

I braced myself in case he told me to jump. The next ship was already coming. The captain in the lighted cabin was looking straight ahead.

“Which bridge?” he said.

“The Gerrit Król Brug.”

“How did you end up there?”

I glanced at Kafka, who was still busy tending to the thing in the box. “Someone gave me a ride.”

My son’s voice went under, swallowed by noise. Then it plopped back up. “…want me to come get you?”

I started to feel my lips, cold and swollen. “Meet me half way. I’m tired.”

We hung up.

Kafka closed the lid of the box. “Have we finally decided?”

“Let me stay a little,” I said. “I need to warm up before I can run.”

“This is a cold place.”

“It’s a way back,” I said.

Kafka spread his arms. Once I was inside his embrace, he wrapped the coat around me. It reached down to my ankles, warm and dry and silky on the inside. I clung to his body. Before going home to my family and my failure to keep it whole, I wanted to gather strength.

- Published in Issue 18

PURITANICAL LIFE by Mike Itaya

I am not a well-loved man in Plymouth Colony.

I’m a man-hussy where it’s so buttoned-up folks wear cods to marital bed. For loo-looking and varied lowercase perversions, the bailiff, Mr. Ben, will crack your chestnuts. For just saucy whistles, Mr. Ben strung up John “Horndog” Smith by his ween, to give you an idea.

Five am: Holy terror Friar Mitchell’s whanging the Prayer Bell, and I can feel Eve’s mead in my brain. I put a hustle for Meeting House, but inside, before I knock the ice off my boots, Jenny Rodgers opens a cat-bag of crazy and thrashes me with my own damn buckle-hat—which has “bottom-feeder” writ upon it. Sensing a foul turn, I run out the Meeting House, jump on my hoss and lick a path out of town.

I head towards Grafton to see Sally Hirshfielder. Sally and I share a genteel epistolary—her steamy epistles give convulsion to my trousers—and I mean to ride to Grafton to boink the daylights out of her.

But outside town in waking dark, it’s cold and my mange-blankie is a bit holey. All the naked trees look like Jenny Rodgers about to hit me. The sun peeks over the butt-crack horizon, and I scan the rank day coming. I have the heebie-jeebies, and my heart is threadbare.

Town is a God pile of shit. Back in Colony, the passing years stack like leaden weight in my chest. I utter terrible oaths with the alchie sexton that frighten his dog. And every lightning storm I dare God might smote me and get done with it.

And that’s it: What if all the things you looked forward to was dreadful words you were too chickenshit to name?

Aging weren’t easy in the shadow of a holy terror like Friar Mitchell, and short my demon winds during Fall Festival (when three-bean salad bedeviled my bottom), I’ve never felt the Spirit. My grief stopped not there either. In December, I drank enough Eve’s mead to build a mighty pressure, and neglecting fitter spots (and from elevation of town scaffold), I shot my wicked stream into the bonfire—which gave rise to a demonic stench and mighty displeasure. Soon enough the next am, I woke to the pounding of both the Prayer Bell and my penitent noggin and a homily about my “pissfire” caper, which sounded shameful in the light of day, but also a bit sensuous. Sensuous enough I cranked out a half-chub behind the grain house.

Again: I am not a well-loved man in Plymouth Colony.

Out on the pot-holey road, I encounter a fresh lad hawking spendy artisanal quilts and mealy veg. I contemplate a wormy potato and wallop him right about the head with my cudgel. I pilfer more than need warrants all while taking pains to kick him in the chest for gratuity.

These days, I have little to go on save Sally Hirshfielder of Grafton. By parchment, I dispatched her a request to “Send Noodz,” and upon my lonesome grave, Sally did not disappoint.

Following Sally’s directions (writ in crude hand), I come upon the house, a drab number. A single-window wank-tank, out of which an occupant leers with portent. My unfed stomach compels me forth with mixed message. I’ve had nothing to fill save sad snackie of rotten, robbed carrot and depressive taters. And I didn’t shit in the village, as it was rush hour for privy.

I beat the door with my cudgel, and when some fish-eyed hermit opens a crack, I muscle in. It’s not too grand in there. It’s damn dark and a bit funky—I bead a few stuffed voles and an easel—and whether it’s the room, the hermit, or me, it feels colder inside than out. Looking around, I get an uncomfortable notion Sally Hirshfielder might be a lonely mad-man drawing pervy pictures in this sad spot. That’s what was coursing through my noodle when the hermit brained me but good.

And in the dream that came, the sun was direct above, like God had opened his giant eye to leave none in darkness. I was out in this field, and all the women were in white, fresh-stitched skirts, and something was cooking over the fire, and people—folks I have done mighty bad things to—were really glad to see me, and I’m not ashamed to say, I felt loved. Like, love. Some youth put dandelions in my hair, and I never wanted to leave. I felt love all around me. I wondered what I had ever done to deserve such a thing.

Then I woke, and I was ruined. I could never speak its name.

- Published in Issue 18

QUINTESSENCE by Clifford Thompson

In the early morning, before anyone else is awake, the orange-yellow glow of the shaded lamp cuts the gray semi-darkness. Beside the lamp, on the sofa, you half-sit, half-lie among the cushions, reading a book with the help of glasses you have needed only recently; with a small device and earphones you listen to wordless music. The early hour, the dullness of the book, the rise and fall of the notes weaken your concentration, and without your knowing it, your eyes close. For moments you hang between this world and that, with the music as the link, but slowly the music carries you deeper, the gentle, woody, thoughtful clarinet line following a labyrinthine path, your path, through the terrain of piano notes long and short, tall and short, rising like buildings, stretching like streets.

On this gray street, between buildings of large, evenly cut stone, structures that run the gamut from gray-white to deepest black, all beneath a cloudy colorless sky, you walk, no one else in sight. To a rhythm you dimly perceive, you step, step, step in wing-tipped shoes and elegant, straight-legged, vaguely striped trousers—that is what you call them here, “trousers” … To your right, among all the sharply cut stone, you see a plate-glass window, with fanned letters reading “CAFÉ,” and you enter to find that it, too, has many variants of gray, the inside stretching back far, neither empty nor full, some of the many booths taken by lone people, others by groups of three or four. You sit in a booth. The waitress comes. Black hair falling to her shoulders frames black eyes that look at you knowingly as she hands you a cardboard menu and asks, “Do you know what you want?”

“I think I do, but I need a minute.” She turns and leaves quickly, almost as if offended. You hold the menu in both hands, the patched elbows of your tweed jacket on the table, but your eyes slide over the words like feet on a newly waxed floor. Anyway, it’s not here, the thing you want. But would you know it if you saw it? Does it have a name you would recognize? The thing you want is more of a feeling than an object, you realize: the feeling that what you’re doing gets to the center of your purpose, you core, your—

She is back, notepad in hand. “Do you know,” she says, conveying sympathy, “what you’d like?”

“I thought I did,” you tell her in a pained voice.

“Concentrate,” she says, the hand holding the notepad falling slowly to her side. You feel both grateful and guilty. She is a waitress, serving you for lousy money yet, it begins to seem, invested in you somehow, willing to do more than bring you coffee and cherry pie.

All you know to do about your guilt is try to help her help you. You stare at the columns and rows of booths. The men in ties, their fedoras hanging from gleaming hat racks beside the tables, the women holding cigarettes between dark-nailed fingers—all their faces nowhere near old and yet no age you’ve ever been or ever will be, as if they have progressed through their years via an alternate route—it’s all right, and yet there’s something else you seek, something, something—

“Quintessential,” you say.

The beginnings of a smile are on her face; she is pleased and surprised, as if you have come through after she had given up. Putting her pad and pencil in the pocket of her apron, she says, “Let me show you,” and walks away.

You follow. She stops at a narrow wooden door between two booths; you might have thought it was a broom closet, had you noticed it at all. She opens the door, and in the dimness you can just make out a set of wooden stairs. She goes up ahead of you, quickly, noiselessly, but when you try to keep up, you find the steps so short—half the length of your feet, if that—that the toes of your wingtips slam into wood each time; over and over, you stumble, catch yourself on the thin metal banister you can barely see, and start up again. She has disappeared by the time you reach the partly open door at the top. Just as your hand touches the knob, you smell something pleasant, a mustiness, one that you know from—

Yes, you think as you step through the door onto the old, dark wood of the floor, with an eighth of an inch of black space between some of the planks—

Books. They are piled high on many tables, they fill shelves that stretch to a high ceiling shrouded in darkness above cymbal-shaped hanging lamps. You wander among the tables, here and there dragging a finger across the surface of a book, then hear a gentle male voice: “May we assist you?”

You look to your right. Behind a counter that might once have been a bar in an Old West saloon, a bald and bespectacled man stands smiling, and beside him, also wearing glasses, also smiling, clutching a clipboard to her mohair sweater, is—the waitress.

“I think you already have,” you say, winking at her, trying to cover your confusion. She winks back, seeming to laugh, seeing through your façade.

The hanging lamps give the room a yellow-sepia cast. You pass rows of shelves, see single people perusing volumes, before choosing a shelf at random. The book you pull down has poetry, its imagery conjuring colors and pictures, its rhythms like music, like the clarinet music that brought you here—and suddenly, you hear that music again. Its rhythm is gentle, but persistent, and you think: what is the essence of rhythm but time? And what does time do except pass? This thought is vaguely disturbing, so you ignore it, focusing on the book. Reveling in this verse, you sit on the floor and recline, a pile of books conforming to the shape of your back. You let go of the book of poems, pick up another book from where your hand has fallen, read its passages of memoir about dressed-up important men and women holding drinks and talking quickly about what’s interesting and vital as the music plays, and you think, Yes, very close to the quintessence, and yet—

“I’m not there,” you say aloud. “I’m not doing it. The thing that I’m supposed to be doing. And”—you remember the clarinet music; is it still playing?—“time is running out.”

Your words seem to bring her to you. “Well then let’s go,” she says, stretching her hands down toward you, and you grab them, surprised at their firmness and her strength as she pulls you to your feet. You follow her through a maze of shelves to a door leading to a metal staircase; these take you down to any alley. Ten feet wide, made of cobblestone, this alley seems to have no end in either direction. The same is true of the building on the other side of it, its once-red bricks black from decades of industrial grime and soot, its walls so tall that its top is a silhouette against the sky. A fire escape hangs low, and she jumps, grabs on, pulls herself up. You follow. She disappears through a window above you. You follow. You climb through the window, from whose wooden frame white paint is peeling, and the first thing you see is her sitting behind an oak desk, wearing a jacket, tie, and fedora and pounding away at a manual typewriter. Others do the same around her at desks arranged in rows over a vast floor with large black-and-white checkerboard tiles; still others walk between the desks, wearing suspenders, shouting, but never shouting at her, at the—waitress?

She sees you and says, “Find a desk. Start writing.” Her voice is commanding, and now it feels ludicrous that you could ever have thought she was a waitress. No, she is an important person in this place, this place that seems to exist to help you, maybe others, maybe all, find—

“Writing about what?” you ask.

“The art show.”

“Shouldn’t I see it first?”

Without looking up she points to your left. You go to where she has pointed, down a gray-painted hallway with open doors on either side, some to classrooms, some to offices, some to film screenings. At the end of the hall is the art gallery—paintings with simple, representational figures and bright, bold colors, work you find so exciting that you hurry back to the newsroom, find a desk, roll a fresh sheet of paper into the shiny black and silver manual, make the clack clack clack of those first keystrokes—as satisfying as the first swallow of cold beer or good coffee—each letter carved clean in black into the gleaming virgin white, clack clack clack about the paintings, their forms, their bright reds and yellows and blues, and then… you stop, bewildered.

“It’s not me,” you say. But now you know what to do: you pull that sheet from the typewriter, put in another, and start to write, not giving thoughts about someone else’s art but making your own. You go deep into your experiences; some of it is real, some made up, but it gets at your essence, your story: the years of your life spent doing things because these were the things people did, all the while feeling a tug from another direction. You’re writing it now, you’re cooking now, and yet…

“Well,” she says, standing in front of your desk, “what’s wrong now?”

You point down the hall, where light from a film screening flickers on the walls. “Down there,” you say, “outside, all around, there’s a big world to appreciate, so many things to take in.”

“And you were doing that.”

“Yes, but it came to feel empty, it didn’t feel like mine.”

“And so you started to make something that was yours.”

“But that just closed me off to what was around me.”

“What is it,” she says, “that you want?”

“All of it,” you say.

“At once?”

You hesitate a moment. You begin to speak but stop because you hear music. The clarinet music. It is much the same as before, but with a new urgency, making you aware, really aware now, of time. Time brought you here; you are an event in time. But it is a friend and an enemy. It gives meaning to the things you do, but—and?—limits your chances to do them. So what is it you must do? You have tried, and searched, and… Ah. You begin to relax, even as you feel the urgency even more.

“I’ve got to get out of here,” you say.

She follows you this time as you head the only way you know—the way you came: down the fire escape, across the alley, up the stairs, past the books, down the stairs, through the café, and out to the still-empty street. In the street, the music is louder. You stop, turn to face her. She takes your hands, looks into your eyes. You can’t find the words, and she, who knows them, won’t say them aloud. But in her eyes you see approval. You give her hands, these gentle, firm hands of the universe, a final squeeze. You turn and run.

- Published in Issue 18

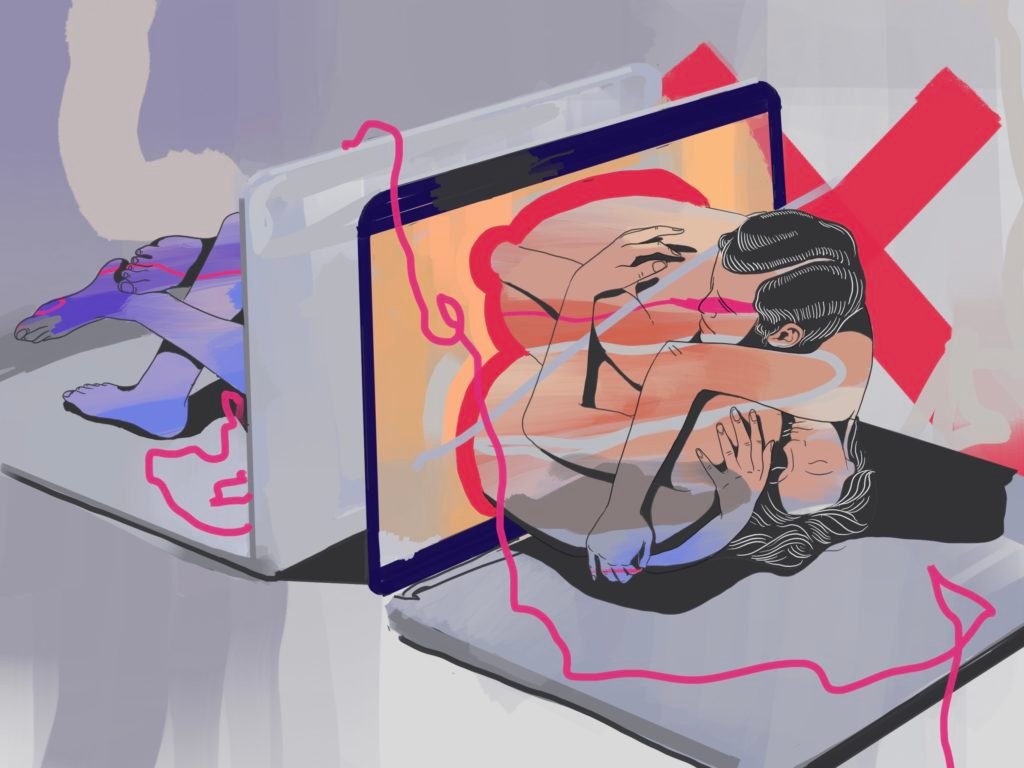

THE THREESOME by Adriana Rambay Fernández

Yasmín and Berto became one body while Linda remained a constant voice in their ears, sounding cool and detached as she issued instructions.

“Roll up, release the clutch, and rock in place for thirty seconds,” Linda said. A virtual fertility coach, Linda knew and understood the couple’s internal frequencies better than they did.

“Dock and lock in,” Linda said, attuned to their every jolt and vibration.

“Locking in,” Berto said. His legs and arms entwined with Yasmín’s. He tightened his embrace.

“Locking in,” Yasmín said. She leaned into Berto and he into her, and then they rocked, shaking the headboard, which creaked from a hairline crack spreading like a vine from the middle.

Linda was a presence without physically being present, like an invisible watchful eye that saw what they weren’t seeing, sensed what was beyond their understanding. She was a couple’s last resort to make the impossible possible.

Yasmín had never met Linda in person, but she pictured her in a cocoon of sorts: in an air-conditioned booth with soundproof walls. She imagined her wearing blue scrubs and clunky white clogs, her feet up on a small shelf, her pants’ drawstrings twisting in her fingers like an umbilical cord stretched out beyond the belly button. Maybe Linda was thinking about Sunday dinner and what she would cook for her family of five. Maybe she was bored of her monthly calls with the couple, which had gone on now for six months. Maybe she was disturbed by their lack of success, how they were ruining her baby-making record.

“Yasmín, tighten the notch,” Linda said, without inflection. “Hold for sixty seconds.”

Even though they had practiced several times during the week, it was difficult to hold still without sliding around. Linda didn’t want them to sweat. She required the room cooled to icebox levels, the use of white bamboo sheets, and several industrial-sized fans. Still, their bodies developed a cold feverish sweat. They were slippery like eels. Whatever hair wasn’t stuck to Yasmín’s face flew into Berto’s mouth from the gushing fans. He couldn’t cough lest Linda call the session over and charge them full price. They had to allow for deep listening, connection, feeling.

When Yasmín was seven years old, a nurse’s scolding was enough to make an infected blister on her inner heel disappear. The nurse shouted at her for an hour, breathing fire and spit, until all that remained on her heel was nothing more than a circle of pink, waxy flesh. The nurse told her it would have been better to chop off her foot to cure her of her stupidity. Yasmin had refused to let the blister heal, peeling it raw each time it formed. Before the nurse’s discovery, Yasmín had lived with the blister for months, hiding it from her parents, allowing it to fester into an oozing red bubble. She still had a scar, indented and round, large enough to fit the print of her thumb, a spot gone completely numb where she sometimes felt residual pain, as if the blister continued to pucker from within. If her parents were still alive, she would tell them the hurt was of her own making. She let things get out of control.

And how do you bring forth a baby when no moment is ever perfect? There was always something. Yasmín felt a strange scratching sensation inside her vagina. She had spent the morning at the beach after Linda prompted her to get more vitamin D, swim in mother earth’s embryonic waters, and walk barefoot in golden sand. Yasmín did it all, and now, the golden sand was likely scraping against her walls eliciting pleasure mixed with pain. Yasmín worried the sand would latch onto Berto’s semen and become part of the embryo. She wanted a child but not one formed out of discomfort. What if it was born with a grain of sand in the eye? Could they dislodge it with a strong gust of wind, with a burst of breath, with the fans on high?

After years of trying and failing, Yasmín wanted to do it right. She needed Linda in her ear, telling her how to move. She needed a scientist and savior, healer and witch to circumvent what was likely destined to be: Yasmín and Berto childless, living out their lives in their tiny beachside home with no beings to call their own other than a murderous cat and a lazy dog until death did them all in.

“The release is imminent,” Linda said. “Standby.” Even with her unchanging robotic voice, they felt the urgency.

“Standing by,” Yasmín said.

“Standing by,” Berto said.

Yasmín bit down on Berto’s shoulder while his nails dug deep into her back. They both wanted to scream. Instead, they held their breath to the very end.

“Initiate the baby thought,” Linda said. “Invite them in.”

Borja perched outside their window with a vicious look in his hazel-green eyes and a mouse trapped in his jaw. It was their large cat’s nature to kill small creatures and leave them on the porch. But the mouse was still alive, flailing its fleshy pink hands, pleading to be saved. “Stay with me,” Berto whispered, through clenched teeth.

Yasmín squeezed her eyes shut, yet the image of the desperate mouse remained. She pressed her lips to Berto’s ear and whispered, “We’re not alone.”

- Published in Issue 18

I AM WRITING A LETTER by Martha Silano

to grief. I am thinking my letter will need a stamp,

the one from when they landed on the moon.

The mail carrier will arrive

in his royal blue shorts. I will hand him my letter,

and he will hand me a small bundle

of nothing I want.

The envelope will be neither heavy nor light.

When the letter arrives, it will open

like the swirling birth of a star.

Feverfew. A heart pin made of broken seashells.

A cup of Roma. A crossword puzzle clue.

I am writing a letter

to the last star because the universe will someday

collapse. It takes a star 50,000 years to reach

adulthood, but everything dies,

including stars. It is interesting to learn

what is expected of me.

My husband says

I am taking it very well. I told a colleague

I am managing. Like when I managed

an office, answered the phone

in a fake-pleasant voice. Grief is placing its lips

on my hippocampus, that lizard part

of the brain that still hasn’t

caught up with her death-rattle breath.

I am writing a letter to grief.

A framed photo of her

and my dad keeps sliding off the mantle,

which of course I’m taking

as a sign.

I am writing a letter asking the mice to keep their distance.

It won’t be written in a fancy font. American Typewriter,

like her gravestone, a limestone rock.

I told a colleague I am managing.

My letter of grief will fill

the mail carrier’s sack.

- Published in Issue 18

NOTICE OF REMOVAL by Michael Pontacoloni

Every maple leaf stiffens to an open hand

of do you have my keys? Against a cloud,

the comma of a crow. In a bare tree,

the semicolon of two crows.

It snowed last night then melted

by sunrise, but notice how the ground

is lower, more within itself,

flannel-wrapped and quiet.

O November. Muss up my hair

like a squirrel in the road.

Fill my lungs with juniper needles

and the brown slush at the curb.

Forgive me, for I have stapled my name

to the trunk of a lover on the seasonless coast

of California. She sends blank postcards,

smackbright photos of Nob Hill

or the hot guts of Sonoma, orioles

and slack-skinned pink condors.

Toss them with coupons against a chain-link fence.

Let me not mistake that gloss

for your first thin layers of ice.

A frozen pond alit with a flock of crows

is the night sky’s negative

and more believable.

- Published in Issue 18

PARTNERS by Taneum Bambrick

When I had sex with him, I got sick.

For the majority of a year I suffered at least

one kind of infection. I was instructed to sleep

with a tablet of boric acid inside myself.

A doctor said, this could kill someone

if they swallowed it but I already knew.

In Tucson, I had mixed it—a rubbery powder—

with sugar and water in bottle caps.

Scattered those near cracks where cockroaches

rose from the basement. At night,

they preened their wings with poisoned legs

before returning to their nests. You can understand

why you cannot receive oral sex.

Some bodies are not compatible.

It can take years for the woman’s to adapt.

- Published in Issue 18

BULLET PARTS by Adrian Matejka

Primer (Brass + Lead)

The bullet base is made from the kind of brass that otherwise

would have been a classroom doorknob or cheap ring at one

of those prequarantine gathering places with games of chance

& lights that surprise & delight. Or molded into new French

horns for the underfunded youth band—no solos for the hornists,

but they are still vital to the orchestra. At the center of the brass

base: an igniter made out of lead. An igniter is only good at exploding,

but the lead might have scratched its love in meticulous notes

with old-time penmanship. Or become part of the paint behind

a Periodic Table of Elements in the back of a public-school

classroom: Pb, atomic number 82. It’s right there, lining Roman

aqueducts & wine vats at the other end of the empire. It’s right

there, holding reactors & their radiations close as a friend in need.

Walkman batteries running out in the middle of a slow jam again—

the voices get thicker & deeper in the lead correction. In some other

life, the primer probably would have gone in another direction.

Propellant (Gunpowder or Cordite)

Gunpowder, like poetry,

was mistaken for an immortality

potion. Poetry, like gunpowder

was first used to light up

the sky with every color outside

a summer window. 700 AD,

& the first propellant welcomed

the new year with combustible

surprise & eye-covering brightness.

Gunpowder: easily mistaken

for medicine, raising dragons

& open-palmed stars bird-level

in the sky while cordite can’t be

anything other than the killer

it was mixed to be. Since 1889,

nitrocellulose, nitroglycerine,

& petroleum jelly—a murderous

clique. Cordite is only good for killing.

Since 1889, cordite has made killing

safer & easier for the red-faced killers.

Case (Brass or Steel)

Brass again, wishing to be a lost key or a better Victorian decoration. Brass again, wanting

to alloy in a gentle fashion. Steel, too, taken from ship sides or the skeletons of skyscrapers.

Steel can be a fist-bumped architecture, full of the empty seats fans used to sit in. Or car bumpers

dented in claustrophobia. The STOP sign nobody slows down for when cops aren’t around at the

fork in the road. Forks in the drawers of the local establishments that only serve take out now &

butter knives for the drunken disagreements, past & future. Nerves steeled by food & beer. Abs

of steel, too, in the old commercials on the TV in the corner.

Bullet (Lead + Alloy)

Lead in the belly, copper

& nickel skin in abundance

each year. 10 billion bullets

made in the U.S.A. each

year. Enough bullets to kill

most of us twice each year.

The bullet hits 3 times

faster than we can hear

its concussion. The bullet

breaks the air with its 2,182-

mph admission. The bullet

is a grim onomatopoeia

for itself. The bullet is

a slim allegory for a gun

happy nation & its attendant

segregations. Lead belly,

wrapped in the grinning

freedom amendment:

the gun is always more

important than the people

in front of it as the antagonists

tell us. & here we are again:

so many black women

& black men in front of it.

- Published in Issue 18

EVENING THOUGHTS by Alisha Yi

I barely recognize it. The sharp fence in

the waning desert. It’s so compact inside,

it’s hard to see behind the window. But in

every angle, I can see the city behind it.

The night, birdless. Unnegotiable. I like

to think I’m somehow making this land.

This endless expanse, blown over. Except,

I cannot enter the city. I’m far from it.

It seems like the world has changed,

and I am at its edge. In this room, I wait and

see, the neighbors passing, again and again,

until they leave the frame, the brown gate

and its ruts, the rustic ground. I wonder

where my neighbors are hurrying to.

How many more days I will spend

watching and waiting. I try to feel

invisible. And the night adds

to itself. It excels at filling time.

- Published in Issue 18

- 1

- 2