Lipochrome by Nathan Poole

“…God will give you blood to drink.” –Sarah Good

It did not go away—as everyone said it would. At nine months Ida was diagnosed with an obscure disorder. It was thought to be caused by an infection in the eyes at birth, a condition that amplifies the production of the rare pigments in the iris, increasing them until they dominate the eye. When most babies’ eyes shift from the lapis slate of infancy to their final and common color, Ida’s eyes turned wolf yellow and remained that way. They smoldered under her white bonnet like filament at low voltage.

This was startling to everyone. To her parents. To those who cooed at babies and drew close to see her. To those who lifted her cap to peer in at the bland, lost little face, and found those inquisitive, lupine eyes.

Soon people lost their inhibitions completely. “Can I see?” they asked, waving and jogging toward her mother across the square that divided the cemetery from the church yard, following her into stores, down the produce aisle. Ida’s mother would often turn to find a strange man standing behind her, cornering her against the lettuce. No introductions. “Mind if I have a look?”

And what could she do? She would turn her child from her shoulder, bob her on her forearm and let the stranger’s eyes stare into Ida’s, “Ain’t that a thing,” some said. “They’ll go away,” said others.

What happened when Ida was fourteen was in many ways inevitable. She had been so long an object of curiosity—a kind of unconsummated desire—and the rumors had been in the wings from the beginning, jealous and impatient understudies, anxious for their turn on stage: “I bet she has a forked tongue,” “I bet she howls at night.”

In church that morning Ida had been holding her late grandmother’s wedding band in her mouth. She was bored and had taken it off her finger and was flipping it over and over on her tongue while the reverend, a soft-eyed older man named Quatrous, was preaching the prophet Amos.

After church her mother stayed and talked while Ida wandered outside to wait on the warm church steps. From there she saw a horse standing across the street in the shade of a tremendous live oak. It was tied by the bosal to an ornamental iron fence capped with sharp hand-hammered finials. The fence had been there for a hundred years and it lifted and sunk where the roots of the oak pressed up beneath it, causing sections of finials to aim inward in concave depressions and others to fan out lethally like the rays of the sun on old celestial maps.

She was moved toward the horse by a restless feeling the church service put inside her. Like the residue a flash bulb leaves hanging in the air—an exposure that turns with you when you turn and stays out in front of you when you close your eyes—the long stillness of the hour had made the world distant and unreal and the horse was a part of the dream. She wanted to touch the tight tendons of the leg, wanted to run her hand over the muscles and across the steep hill of the flank.

As her hand neared the horse’s front shoulder it seemed a spark left her finger tips, and if not a spark, something like it, something inside her, something she carried that leapt. An invisible surface was breached. The animal spooked and reared and she fell back and watched as the horse grew tall and then taller again, impossibly tall. It came down near her, the hooves clattering on stone. A taste of iron in her mouth, a notch in the tip of her tongue. The horse went up again and she watched as it tried to clear the old iron fence. She watched as the mecate caught and she watched still as the historic finials disappeared into the smooth barrel of its underbelly.

The sound it made was significant, married to its meaning. A song lived somewhere inside the sound and it drew men toward it. From the far end of the road, and from around the corner, and from across the street, they hustled toward the sound of the horse. But the noise Ida heard had not come from the horse but from somewhere inside her. The sound was the sound of her mind when she saw the horse descend, it was the sound of a sawmill clutch before the belt gains, the sound of resistance, of wishing it could all be turned back, the sound of a loud blister in her palm after a day of raking leaves, the long wooden pews creaking, the organ growl, the doxology, pedal tones that are felt before they can be heard. It was a sound like the nameless world.

The horse’s front hooves pawed and reached for the ground while the animal remained suspended. On the sidewalk, in the shadow, it seemed the horse was running hard in a four-beat gait and the shadow was something projected out of the horse, some vital extension escaping.

The mare bled out from its barrel. Its large eye widened above her. She watched the eye as the blood left the horse, black ink streaming down the scroll work, over the nodes and twisted pickets. The big eye rolled languidly and then centered itself like the by-point globe inside her father’s liquid compass, regaining its mysterious traction to the world. She watched the eye work to stay in the world, to keep a hold on it.

Men seemed to come from everywhere then. They mobbed around her, shouting to each other, crowding in. Their boot heels slipped in the blood, streaking it with clay. They scurried around the horse’s suspended body, over the fence, placing their backs alongside the animal’s body and lifting with their legs. This was all organized by shouting and by something unspoken, the frantic purposeful feeling, not unlike joy, that men take in things terrible and unlikely.

Shouts rose suddenly to stop lifting; a man who did not hear fell to the ground beneath the horse and when he rose his dark suit pants were purple with blood and brilliant in the sunlight. The mare squealed when the lifting stopped and stamped its back legs and the men around it moved away and the horse descended only farther into the finials until it stood with its front hooves on the ground. It rested. It contemplated its pain.

Everyone on that corner knew it was Quatrous’s horse and that he had just bought it the week before. He was one of the only men in Shell Bluff to still bring a horse into town and it was only on Sundays. Quatrous made the decision. He stepped out of the church across the street and without looking twice at the scene—the men sweating, their feet slipping in the blood—he asked one of the police officers for a pistol.

Ida had been carried across the street and propped up against the trunk of a large sweet gum tree. Her eyes were glazed and the world inside her pitched and turned. Her mother took off her shoes and threw them away and held her face and stared into it and saw nothing but the vivid gold eyes, focusing on nothing. The pistol snapped, ringing the air between the short buildings, and the horse sunk entirely into the finials as a large flock of pigeons rushed out from the limbs above Ida’s head.

The women in the prayer meetings shuddered to hear each new story—though they, most of all, spread them around—and would then commence to praying for Ida and her freedom from what they called her oppression. Many believed the incident to be associated somehow with her grandmother’s wedding band and wished her to take the band off.

Ida’s grandmother had lived with them for as long as Ida could remember and her presence in their house was robust, solid, heavy with laughter. Her grandmother seemed so physical an object, and by comparison her parents, who were not affectionate people, seemed frail, as if strong laughter would sift them right out of the world like ash.

Ida would sit with the old woman in the evenings for hours and run her fingers down the large distended blue veins in her hands, tracing them as they warped over the bones, pressing them down and watching them grow faint, disappear, and then appear again. Her grandmother never resisted being touched and Ida loved this about her. She would let Ida do her hair up in all sorts of bizarre arrangements, twists and bows with confectionary zeal, everything short of cutting it, and the grandmother sat with her eyes closed, drifting in and out of sleep.

Ida was twelve when her grandmother died and her grief was immense. The wedding band was left to her for her own wedding day, but she refused to leave it in its envelope in the stationary desk. She screamed when it was asked from her and the screaming rattled her mother’s nerves. She was allowed to wear the ring, with the condition that she was only allowed to wear it on her right hand. It fit loosely on her slim fingers and Ida developed the habit of keeping that hand pursed into a fist when she walked or ran, giving her appearance a new ferocity, as if she were perpetually charging up to sock someone in the mouth.

After the horse died a series of stories developed. Desire was let free. One of the first stories that circulated throughout Shell Bluff—and even beyond, into Milledgeville and Sparta—was one that a number of people attested to seeing personally. Her grandmother’s wedding band would disappear from Ida’s finger and reappear in her throat. It happened at school. The ring appeared suddenly in her throat and was trying to choke her. Ms. Addison slapped her firmly on the back and out fell her grandmother’s ring onto the floor.

“Why’d you swalla that?” the teacher asked.

“She didn’t though,” said another girl. “It disappeared right off her finger. I saw the whole thing. It was there and then it was in her throat and she was choking. It showed up in her throat. I saw it all. I saw the lump in her throat. It’s trying to kill her.”

The word “booger” and the song, “Ida and her booger sitting in a tree…,” became a musical phrase that lived in Ida’s landscape, a bob-white’s call, a whippoorwill. The sounds of the words and the notes of the song were factual things that traveled through the air and scared her. She was oppressed. She was prayed for. All of it scared her.

Soon Ida hated being left alone, certain now, after all the words, and songs, and taunting, and prayers, that when she was alone she was not. Her fear of being alone, the fear itself, fed the rumors and as the rumors grew so did her reluctance to be around too many people, or too few, or to come near an animal, any animal, which could be difficult when almost everyone in Shell Bluff owned some number of livestock.

There were other things to reignite the story whenever it seemed to be dying down: a girl said she had a secret to tell. Her name was McCuen. She had six brothers all called by the same last name and no one knew their first names. They were McCuens. To call one was to call them all, but for Ida, McCuen was the girl who reeked of kerosene during the short Georgia winters. She was the girl who lived with her tribe of brothers and was skinned-kneed and ugly in appearance despite the fine features of her face and the way her eyelids lay softy over her almond shaped eyes, as if they were perpetually half-closed.

McCuen led Ida by the hand into the bathroom stall and instead of disclosing a secret began to softly stroke her arms, and then her cheeks, and hair. Ida felt the pressure of the girl’s hand on her head and then the hand moved to her cheek and then to her shoulder and Ida’s heart began to pound and at the same time she struggled to keep her eyes open, as if she were running full speed into sleep.

After the first kiss Ida let her lips part and McCuen kissed her again and it summed in her mind into a litany. It was a hot afternoon on a bank of red maples turning suddenly cool; it was water dripping off her fingertips, tugging each finger toward the ground with invisible force; her hand was swollen from a wasp sting, a hand that was numb and large and didn’t feel like her own when she touched it with the other; it was six pieces of coal she once found in her school desk, black like sin; it was soft like owl feathers and heavy like fruit.

They might have kissed a thousand times—it seemed an infinite space between each one. She never kissed back but it did not matter, she did not have to. They came one after the other. There was another girl there who saw them standing together, who had walked in quietly behind them and saw their shoes staggered in, facing each other. And she could tell, she just could, by the position of their feet and the odd silence, and she knew what was happening. It was this girl, hurt with longing and self-consciousness, who told her mother what she had not seen but knew, who told her friends that she had seen what she had not, who told everyone she could that Ida had seduced McCuen with her witch eyes. Then she added to the story as it needed adding, added that she heard them speaking together, in one voice speaking, and that they spoke in a language she had never heard before.

Ida’s parents received visitors who offered their advice, who spoke of how they had cured their own children from similar dispositions. McCuen spent two weeks out of school and no one knows what happened to her those two weeks, but when she returned to school she never looked at Ida again.

A few months passed and Ida was exhausted and numb to everything. She avoided animals completely, certain that whatever was with her would scare them, cause them to jump off of cliffs or hurl themselves on sharp objects.

Ida would be made a member of the church in early August. She completed her membership class uneventfully and the date was printed in the church bulletin with the names of the other children to be made members. The following week Ida’s named stood alone and the other baptisms were all rescheduled.

On the afternoon of the event Ida was picked up along with her family by a tall young man with greasy hair who drove a long pink Buick convertible. He introduced himself as Jimmy. Jimmy had just come down from Columbia with his new wife and was excited to be part of the occasion. On hearing from his brother-in-law that there would be a baptism he insisted on driving the family. He treated them like prominent figures in a grand parade. He left the top down on the Buick. He spoke loudly, over the radio—which he did not turn down, even as he pulled into the church parking lot to meet the caravan that contained the minister and what seemed a large number of cars and trucks that would follow them to the river. Compared to her father’s truck, the Buick went smoothly, suggesting the familiar road with its washed out creeks and roots while transcending it. Soon the other cars in their party were no longer visible. Ida gave up tucking her hair behind her ears and let it swirl around her face while her mother kept both her hands on her hat and her father wore his dark suit and a tight smile across his embarrassed face.

“I remember my first baptism,” Jimmy yelled at his passengers. “I thought the man wouldn’t ever let me up and when I did get up I tried to sock him in the face. He was messing with me. I swore he was. He looked small to me and I thought I could take him but he was strong as an ox. God. He was strong. He threw me right down again into the water and held me there until I gave up.” He reached back and slapped Ida on the leg and laughed as the Buick veered slowly toward the tree line. He corrected into the road and aimed the rearview mirror at her. “So don’t try it,” he winked.

“I thought you said you didn’t baptize till you married Q’s little sister.” Ida yelled back.

“Honey, that’s not your place,” her father turned.

“I didn’t.” Jimmy said.

“But you were baptized as a little boy?” she asked.

“Honey,” her father said again.

“That’s true,” he declared, laughing, “I got baptized as a boy but didn’t get saved till I married Q’s sister. I guess I was on layaway.”

Jimmy’s laughter caused the limbs to shake overhead and the light to spill down through the trees. He had tears in his eyes he was laughing so hard and the car was swerving and Ida felt herself being made new. Thurston Harris’s Litty Bitty was playing on the radio and the music was infecting them all. A strange sense of buoyancy entered her bones. She would walk across the water, she would bob like a cork. They smiled as they looked at each other, a family but strangers to themselves, figures made from air and sugar and gossamer, confections from a dream.

Baptisms were carried out in an eddy along the Savannah River where it takes Miller’s Pond Creek. There is a sandy wash a few steps up the creek mouth with good shallow clear water and the current is soft. Quatrous often said he loved the spot. It reminded him of those lesser-known lines from Cloverdale: “Lead me forth beside the waters of comfort.” “You see, the water doesn’t need to be still,” he would say on a Sunday morning, “‘Cause the best water keeps on moving, don’t it. You go get a drink from Telfair pond up above the dam and tell me it don’t taste like a slick froggy. Now go get you a drink from Keysville at the head and you’ll lay yourself face down and say Lord have mercy. Good water knows it’s not done. It’s got a race to run along the earth. Amen? It’s not home. No. But it’s bringing home with it, just not there yet. Who else ain’t home? We aren’t. That’s right.”

As the cars pulled up they could already see it wouldn’t do. The river was swollen and banking violently. The party walked the upstream path together in a single file just to see how the creek mouth looked and it didn’t look any better. What had once been an eddy was a brown churning place. Every so often a log would drift in and spin a few times like it was in a washer and then shoot back out into the river.

The men stood on the bank watching the river surge by, already intoxicated by the level sheen of light—if only it were small enough for them to run their hand across it, like a table top, to examine it, they would. Quatrous took off his shoes and rolled up his pant legs and prepared to wade in a few feet where it seemed the slowest. He needed to see how bad it actually was before he would give up his spot.

“Easy now,” Jimmy said, laughing.

“Woooo,” Quatrous said to the crowd, widening his eyes. They laughed.

“Is it cold enough?” Jimmy yelled.

“Woooo,” he said again, “no, it’s tugging though. It’s tugging.”

He waded back carefully and reached his hand up to Jimmy to help him step out just as he slipped in the slick kaolin clay that banded the bank. He went down on his face before he could get his hand down and the current pulled him immediately out of the creek mouth. As it did he rolled casually onto his back as if he were expecting as much to happen. It seemed like his belly was made of cork the way he shot out into the Savannah, bobbing in the rapids as he accelerated. He was cruising very quickly out of sight, disappearing in the shade of large maples and hickories and then reappearing on the other side moving faster than he was before and then he was gone.

Ida and Jimmy were racing along the bank shouting with others, Jimmy running ahead and laughing so hard he could barely keep Quatrous in sight. Ida’s feet slapped along the packed footpath. She caught glimpses of Quatrous, down low close to the bank. He would occasionally roll onto his stomach and reach for a branch overhead and then, having missed it, roll back onto his back to look where he was heading. When there wasn’t a limb to reach for he kept his arms down by his side and used them as paddles to direct himself.

After two or three attempts he finally got hold of a low hanging Possumhaw limb and was immediately stretched out longways downstream so that he couldn’t get his feet underneath him to walk out for fear of increasing the drag and breaking the branch. They all moved to go down when Jimmy grabbed Ida by the arm and said, “No sugar, you stand right here.” He made her hold onto a skinny tree and nodded to confirm that she would not leave it. He and another man went down the steep bank carefully together holding onto washed out tupelo roots.

“You finished bathing?” he yelled down to Quatrous.

“I’m just thinking,” Quatrous said.

“About how to get out?”

“No. About what it means.”

“It means you’re a clumsy old man, is what it means.”

“Maybe. Maybe,” he said, the water streaming around his face, framing his red skin. His thin white hair pasted and pulsing on his brow like a jelly fish.

“Do you want to hear my plan?” Jimmy said.

“Go ahead then.”

“I’m gonna hold onto this tree with one hand and put the other on your arm and when you stand up the current is going to swing us around and pull you into bank and then you can grab onto those roots over there. How’s that sound?”

“Sounds like a plan.”

The rest of the party arrived as Quatrous was crawling carefully up the bank on his hands and knees and Jimmy was making his way up alongside, holding onto the trunks of trees, practically climbing from one to another. Ida’s father held Quatrous under the arm as he stood. The preacher took off his tie and rang it out. “Well, where to?” he said. “We might as well do this while I’m still wet.”

Ida was baptized in a pond off Claxton-Lively road. It was fed by an aquifer and it was the coldest water she could ever remember being in. He put her under and the water ran across her chest and she thought she felt her heart stop. When he pulled her back up she was shivering so hard she couldn’t walk. Quatrous lifted her and carried her out of the pond and she sat down in the hot sand beside it while waves of dizziness, something near ecstasy, shot through her mind and body. The sun warmed her and she thought of nothing and it was in the nothing that the figures and voices of her life swung around her like a globe of stars being cranked and she heard the sound of the Buick’s radio and she felt the heavy light entering her again, an opening in her mind, the opening of a fist.

It had been a little over a year since the horse had died and Quatrous thought it was time to bring her near an animal again. He thought they might give it a few tries, thought he would even teach her to ride and that the sight of her up on a horse would be good for the neighbors to see.

The Latvian was a heavier animal, good for light draft work and riding and above all, calm as a tortoise. Ada was already standing when she saw Quatrous walking the animal around the bend in the road. Her dress was clinched in a ball in one fist above her knee, her other hand on the door knob. Her eyes were wide and tracked the horse fiercely as they came. She stood like a deer at the edge of heavy woods, every nerve balanced. As soon as Quatrous turned up their long drive and it became clear he meant to visit the house she ducked inside.

He knocked on the door.

“Ida, come out here and meet this lady, she’s real sweet.”

He waited. He heard Ida and her mother talking softly.

“You want to know her name? Abigail. That’s sweet, isn’t?”

“Go on,” her mother said.

Quatrous left the door and went down to the animal and petted it and pulled an apple from his pocket and feed it a bite and pulled the apple back.

“Want to feed her this apple?” he called.

Ida came out with an uncertain look on her face and took the apple carefully, keeping her eyes on the horse like it was a blasting cap.

“Go on,” Quatrous said. He motioned with his hand to show her how to lift the apple up. She watched the motion from the corner of her eye and lifted her hand up.

The horse took a step forward, moving her mouth out toward the apple. Ida pulled the apple back quickly and then launched it across the yard into the garden. The horse turned to watch the apple fly and when it turned back to her she caught it on the side of its nose with her closed fist. The Latvian’s eyes grew wide. She slapped it several more times with her palm as it turned from her in a trot. She screamed and caught it once more on the flank with the flat of her hand, sending it into a steady gait out of the yard toward the road. A truck coming down the lane slammed on its brakes to let it pass in front. The horse swerved tight around the truck’s hood, almost colliding with the fender before heading off in the opposite direction along the creek bed. It looked as if it would run the rest of the way home if home wasn’t in the opposite direction. The mother screamed after her daughter but Ida did not stop. She disappeared after the horse, the newly long legs pawing the ground with incredible speed. “I’ll grab the truck,” her mother said. She went quickly inside the house. The screen door slammed.

Quatrous walked calmly out of the yard with his hands stuffed down in his pockets. His head down.

“Damn it,” he said to himself.

As he came to the road he saw the hoofprints where they turned up the packed earth and he saw the ring lying brightly beside the spot in a slick of mud. He put his boot heel on top of it and pressed it down deep as if it were the head of snake. He kicked some earth over the spot to trod it down a second time and waited there for Ida’s mother.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Singing Backup by Jason Kapcala

|

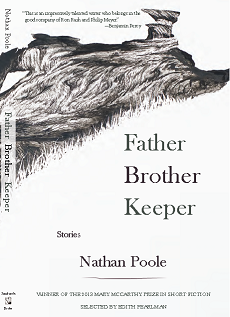

“ Father Brother Keeper is marvelous. To read the work of Nathan Poole is to discover an immense, beautiful secret, rich with private histories and the rhythms of our complex, haunted world. These are stories to cherish, a debut to celebrate.” ~ Paul Yoon Available February 15 from Sarabande Books |

FAILURE by Glen Pourciau

I’d been holed up with a new project, and it seemed time to get out and breathe some fresh air and talk to people, an outcome that the solitary nature of my work sometimes led me to desire more than dread. I’d received an email about an opening reception at an art gallery, the owners of which were two of the friendliest people I’d ever met, and I was an acquaintance of a friend of a friend of the artist and had been to two openings for this same artist at this same gallery before and had seen this acquaintance at both of them. I planned on speaking with him at the opening about my project, and I liked the idea that I wouldn’t see him again for two or three years and could therefore minimize the effect of any adverse reactions to whatever I said.

I arrived about an hour after the opening began, hoping to reduce distractions by giving my acquaintance enough time to view the show. The artist was a specialist in geometric shapes, mainly triangles, trapezoids, and parallelograms, painted in a variety of bright colors and floating against an abstract background that suggested a brooding, subdued turbulence, an occasional gnarly, dissonant tree root bursting through the surface as if hurled by destiny. I scoped out the crowd, an impressive turnout, the usual buzz and nodding and handshaking and knowing laughter. I didn’t feel at ease, one side of the room already rising and spilling me toward the door, the floor on the verge of grabbing me by the leg and yanking me outside, you don’t belong here, leave and nobody will get hurt. The art did nothing at all for me, except for the tree roots, which appeared to have come from another dimension and aroused an almost painful urge to lift the frame or remove it from the wall and check the back to see if some design or pattern could be found there that would alter the context of the front side, and if the front side, seen in this new and broader context, would again reverse you to the back of the canvas, and so on, a type of narrative rotation that would intentionally undermine the geometry on its face. One of the gallery owners approached me, which she never failed to do, and she actually seemed glad that I’d come, though I’d never bought anything from the gallery and knew her gladness must have been limited to such an extent that it barely existed, and who could blame her, yet her face showed nothing but good will. Where does her good will come from? I wondered. I couldn’t imagine how she could think I was worthy of her welcome, worthy of her welcome, worthy of her welcome. As I was saying how good it was to see her, a well-dressed woman walked up from behind me and she greeted her as warmly as she had me and, not wanting to exhaust her kindness, I moved on, deeper into the front end of the L-shaped gallery, and continued to the elbow of the L, where you could inform a staff member if you wanted to buy a painting. Glasses of wine were also available in the elbow, but I turned away from the wine, fearing that even a small amount would trigger avalanches of verbosity.

Sure enough my acquaintance, whom I believed was still a friend of a friend of the artist, did happen to be in attendance and was standing just on the other side of the elbow, though I couldn’t be sure if this chain of personal connections remained unbroken because the artist and the friend of the artist were both rumored to be insane, at least intermittently, and prone to tirades against real and imagined enemies. Whatever the case, my acquaintance was laughing at or with a slender man who leaned in and blabbed a few words that had an edge, that caused my acquaintance to flinch and grimace as the man departed. I saw it as an opportunity to stroll up and greet him, possibly taking advantage of his relief at seeing someone other than the apparent wisecracker, but as soon as he saw me his eyes narrowed and without glancing back he took off for the end of the L, as if fleeing to a back door or a line of shrubs outside to hide behind. I resented his aversion to me. All I’d ever done when I’d spoken with him was share an assortment of views on subjects I could no longer recall. So after hesitating briefly I decided to rise above his snub and dare him to repeat it. Did he see himself as superior to me in some way, and if so on what basis? And who else was I going to talk to? Someone else might appear, but I wasn’t aware at the time of another potential listener. I caught up with him along the far wall, his head turned at an angle as he stared at a painting.

Hello, I said, and he replied with the same word but did not take his eyes off the canvas. How’s your work been going? I asked, struggling for rapport. I’ve been stuck lately, he said and at the word stuck he looked at me as if I embodied the word, or that’s how I took it and with good reason as far as I could tell by his rigid posture and sniffy look. I made a mental note to remember the word sniffy. I enjoyed the sound of it and could use it in my project, perhaps over and over and in this way raise the subconscious nostrils of the reader, a sense engager, engager, engager.

I’ve started a new project, I said, that I thought you might be interested in hearing about. He pursed his lips, his attention directed at the geometric subtleties of the work before him. If you’re stuck you may find something useful in my method. I write down everything at every reachable depth that passes through my mind, continuously, or as close to that as I can get. I have a spare ballpoint pen on my desk and a second spiral notebook in case I need extra materials and I let it fly, scenes and images, words from past dialogues and the imagined thoughts of others, their lies and aversions and judgments, and I want it all in handwriting, no word-processing software used at the outset. I want to engage my entire body and thus strive toward awareness of whatever flows through body and mind to form consciousness. And as the narrative progresses I attempt to work from what was written in previous pages, to dredge interpretations and meanings from that text, to develop a deeper narrative and then to proceed further with an interpretation of the interpretation, spiraling downward and outward at the same time. This method does not exclude the possibility of introducing new events and scenes, but they must grow out of all that has unfolded before them. But the underlying issue I hope to address in this project is the question of whether, on the whole, the source of difficulties in human contact–

At that point my acquaintance, whose name I could not quite remember, raised his hand directly in front of my face, a gesture unambiguously equivalent to a stop sign. Once again he fled, again not looking back, leaving me stunned that he, a fellow writer, could lack any curiosity about my project, and at such a crucial point in my elaboration, as if I’d been describing something utterly trivial or revolting. I stood frozen in my mental tracks.

Then I heard a voice and looked toward the sound of my name, the word calling me back. It was Alexandra, a young woman half my age or younger, shy but inclined to express her opinions. She’d blush as these opinions spilled from her, her eyes imbued with an admirable sincerity, and the redness of her face caused her freckles to disappear. Her head usually tilted forward as she spoke and back as she listened, her mouth hanging open to varying degrees depending on the extent of her credulity. I saw her occasionally at museums or movies and I’d made an appearance at her book club. Before meeting with the group I’d felt a horror of hearing their opinions and had imagined them riding through my mind on horses and lashing it with swords. Still, I’d been grateful to be invited and immediately found them all pleasant and receptive and I retained some regret that I’d disagreed with nearly everything they said about my stories. I’d admitted to them that most of it had nothing to do with what I was thinking when I wrote them, adding that this experience was not at all uncommon for me and that I often wondered as I listened to people’s opinions on any number of subjects whether I belonged to the same race as they did. What could I have expected them to say to that? Did I want to dissuade them from speaking?

I read your story in The Milky Way recently, she said, already blushing and tilting her head, her ponytail swaying a bit, and I wanted to talk to you about it. I read it twice actually, once in the waiting room at my dentist’s office and a second time while I sat in the chair before he came in. He runs late, and I like to read something on my tablet until he gets to me. This one appealed to me more than some of your others. I still don’t get the one we talked about in the book club about the guy who killed his eighty-five-year-old father while sleepwalking. I don’t know if we’re meant to imagine a history that would have provoked the murder or if we’re supposed to think we can be completely different people in our dreams, an idea that appeals to me, but the story doesn’t offer support for either of these interpretations so nothing holds it together for me, even though I’ve thought about it quite a bit and find the tumbling words in the story similar to the way my mind works, but don’t tell anybody.

Her face was extremely red at the end of her statement and I felt relieved to be listening to her, in no imminent danger of making a nuisance of myself.

So with this new story I had an idea that you might say was not what you were thinking when you wrote it and is irrelevant because of that, but I thought you could have the story as it stands and then write a parallel version with the same character and situations but this time the guy is taking Paxil. It would be obvious, I think, that you’re comparing how he experiences things in a different emotional state.

She leaned back then, head moving to her listening position, the redness draining from her face, receding from the center back toward her ears, which were still red and looked warm to the touch.

That’s interesting. I hadn’t thought of using parallel narratives, but in my mind the narrator is already taking Paxil so if I wrote a second version, as you suggested, it would be the Paxil-free narrative. No names are mentioned in the story, and that’s because a side effect of the drug is that he can’t remember people’s names.

Her mouth slowly opened as she assessed my reply and its possibly ironic content.

I like the story as it is, she went on. It’s one of my favorites of yours, along with the one about the baby who speaks German although his parents are both American and speak English. I get it that the child caregiver speaks German to the baby, but the question of what causes him to prefer the sound of German makes the story more interesting. Does it portend a deep-seated and maybe innate rebellion against his parents that will endure and develop throughout his life, or what? The questions raised by the German-baby story drew me further into it rather than throwing me into a funk, but I don’t think I could tell you why. I better get back to my husband, Homer. He’ll get jealous if I talk to you too long. I don’t mean that’s what this is about, but it’s how he’ll look at it. Are you enjoying the show?

Too many triangles for me, but I like the roots.

Me too. Where do they come from?

Exactly.

She left me, her hands twitching at her sides, a jittery sign language that I understood perfectly, understood perfectly, perfectly, just as I understood her impulsive urge to express her thoughts, plunging ahead despite the tension sometimes aroused in the speaker and the listener. It was conceivable that like me she struggled with the problem of whether you were intruding or indulging yourself in an unwelcome way and whether you were doing it intentionally or unintentionally or quite a bit of both. I’d never met Homer, whose wrath she may have risked in speaking to me, but I watched her go to the man I guessed must be him and was happy to see him absorbed in his own conversation.

It then occurred to me that I had no reason to stay a moment longer at the gallery. I was suddenly disgusted by the sight of people’s mouths moving and by the sizes and shapes of their teeth, and I imagined their empty stomachs roaring and them on their way to dinner after the show. I suddenly noticed the number of people avidly scanning their phones and poking whatever they poked on them. How could I have been so self-absorbed not to see it before? I imagined them walking into space with their phones, stepping forward onto down escalators, unaware of the drop as they tumbled forward, or striding obliviously off cliffs, eyes on nothing but their phones as they plummeted. Everything I saw in them filled my mind with noise and static, but what was the cause of my disgust? What did I care what they did with their phones? Did I fear that the mouth movers would angrily pounce on my body and eat me? What an absurd idea.

I got myself going and walked around the corner, not looking over my shoulder for a possible farewell glance from my closed-minded acquaintance, eyes directly on the front door, which a couple happened to be leaving through. They held it for me and I was out, drawing in a breath more free than any I’d taken inside, soothed by the air on my skin.

It was nice to see you, Alexandra said from behind, and the tone in her voice brought on a smile.

I looked back and saw her walking through the door, one of her hands tightening into a nervous grip.

I don’t know why I said that about the alternate storyline with the Paxil. I didn’t mean it. Maybe I wanted to provoke you, I don’t know why, just forget about it. I did think about the idea, seeing the story through a changed lens, and I guess I wanted your reaction.

I wouldn’t change the story, but it’s worth thinking about it in that light. I’ll do that. And I admit I hadn’t thought the narrator was taking Paxil.

I didn’t think you meant it, don’t worry.

She went back into the gallery, her final comment lingering as I pondered its implications. I’d preferred to see my comment about the narrator using Paxil as ironic, but why dress it up with a fancy label when I was simply lying to her and she knew it? How did she see me, I wondered, and how much had I unwittingly embarrassed myself when we’d spoken? So-called experts claimed that language should be used to connect people so why did I use it to distance others and thereby drive myself deeper into an isolated void? They claimed consistently that human contact made you happier, a subject that I questioned and explored in my handwritten pages. I felt strongly ambivalent on these subjects, but I couldn’t deny the simple pleasure at hearing Alexandra say, Nice to see you.

It disturbed me that she might see me as a liar, and though I saw no sign that she held it against me I held it against myself and knew she had a right to expect more from me. I’d been all set to get in my car and begin talking back to the unruly chatter inside my head and when I arrived at my desk to spill out as much of it as I could reach and try to make sense of it, the two warring sides of myself, the misnamed voice of reason and the wild animal that I rode around on without a saddle arguing with each other and trying and probably failing to come to an enduring resolution or peace. My throat clenched as I stepped toward the gallery and opened the door to look for her, into the arena with her potentially pugilistic husband. But why escalate the drama when I didn’t know what would happen? Two adults could have a conversation without anyone having to call emergency services.

Alexandra wasn’t far away, but she was standing next to the same man as before, presumably Homer, who appeared strikingly nondescript. If I closed my eyes virtually no image of him would have remained. I had second thoughts, but then she noticed I’d come back in, and she must have sensed that I wanted to speak to her because she was leaving Homer’s side. Words mounted, rising to meet her, and now here she was, eager to listen.

My latest project is to unburden myself, I told her, speaking far too fast, to heave onto the page the unending internal racket and to rewrite it again and again, each succeeding page and chapter originating from the buried content of the previous sections or chapters, until I reach a conclusion about whether I am the instigating source of the racket and its effects on my outlook or if it arises from the inherent conflict involved in human contact. Does it come from a partly submerged and untamed animal inside me, from networks of confused neurons, or is the noise an inevitable product of a collision between me and others with all parties sharing responsibility for the impact of the crash? I tend to think the source of the noise is me. What you said about Paxil suggests that. If a pill can change the outlook then that implies the problem’s source is within the mind. I wanted to resist the idea of putting Paxil in the story, out of fear that I alone am the cause of my anger and resentment and constant mental yakking, but on the other hand I haven’t been able to dismiss it.

So are you unburdening yourself or increasing your burden? she asked, her head tilting forward, the aptness of her question jolting me. All the words piling up, all the uncertainty in the process, and can you hope to explain the true nature of what you call the racket or to make what it may or may not want to tell you understandable enough to put it to rest? How much can you expect yourself to know or understand and how can you think there could be only one source, you, for what goes through your mind? And in the end, no matter what you do or think, maybe it’s just there and you could decide not to listen to it so much. It wouldn’t go away, but it might help.

Just when I thought we might be getting somewhere, Alexandra assuming the role I’d hoped my acquaintance might fill, Homer walked up, his face taking in mine.

I haven’t had the pleasure, he said and extended his hand, which I shook, though something in his choice of words made my flesh crawl.

Alexandra told him my name and explained how she knew me, her explanation doing nothing to reduce the intensity of his curiosity. He glanced at Alexandra to judge her degree of interest in me, vigilant for clues of a deeper attachment, but she revealed no concern he’d unmasked a secret and no hint that she wished we hadn’t spoken or that I should depart in order to defuse an impending uproar. Homer edged between us, obstructing our visual path, threatened by what he saw as my nearness to her.

His phone went off then, and he apologized to us as he snatched it off his belt. He turned his back to me but kept an eye on Alexandra, putting his hand on her arm.

He’s a doctor, she said.

I see he appreciates you, I said.

Her mouth tightened, stifling a pained smile. Homer gripped her arm tighter and I imagined his hand affecting the flow of her blood, her blood. Anyone could see she didn’t want his hand on her arm, but I cautioned myself that I couldn’t know what forces were at work between them, what words he might say about me on their way home or in their bedroom. I knew I shouldn’t assume the worst of him or make excessive inferences about her stifled smile. But were they excessive? So what did I have in mind, to disengage his hand and take her away from him? Was I the one to be feared, the one most in danger of being driven by haywire emotions?

Alexandra’s blush had reappeared, and as he spoke in a low tone to his phone she removed his clutching hand. I wanted a private word with her, but how could I do that without riling up Homer and therefore making the situation more difficult for Alexandra? Besides, Homer had returned his phone to its holster, and he was telling Alexandra they had to leave, a patient needed him. It was good to meet me, he said, his eyes now looking in the general direction of my face but not exactly at my face, preferring, as I saw it, not to fully acknowledge me. I said it was good to meet him, mirroring his words, I suppose, out of some sense of safe boundaries, though my resignation troubled me.

Alexandra’s blush had not left her, perhaps because he had her arm again, though not as firmly this time. But she didn’t seem afraid, which led me to reject the idea of following their car and pulling up alongside them if I witnessed a violent argument, Homer swerving from his lane, arms flailing. And as I imagined my pursuit I asked myself what got into me thinking like this. Why did I conjure up disparaging scenarios and attribute what originated in me to the motives and behavior of others?

I watched Alexandra and Homer exit the gallery, his hand moving to her back, nothing wrong in that, no gripping, no taking possession, only a touch. She turned at the door and gave me a suggestion of a wave, her freckles imperceptible beneath her face’s redness. Was I failing her? Why did I confront myself with this question? She wasn’t a prisoner and she could make her own decisions, and he had a patient to see.

I had a lot to recount, to weave thematically into my broader narrative, unrecognized elements and echoes to dredge up on my encounters at the gallery. I considered emailing my contact person at the book club to ask for Alexandra’s email. I could let some time pass and then write to her for an update, see if everything was going well for her. I saw it as fortunate that my memory couldn’t call up a clear image of Homer’s face. I told myself I wouldn’t be watching for him wherever I went, at some depth expecting to observe something that would cause me to develop further suspicions about his worthiness as Alexandra’s husband. But if I did happen to come across him at the grocery store, say, I might recognize him or, more likely, he might recognize me. We might stop and exchange a look of recognition. But what would the recognition consist of in each of us? For his part, would it have been limited to a passing awareness of a familiar face? I cautioned myself not to presume to know the obscure density and culture of Homer’s mind, but I suspected it would consist of more.

After giving it more thought I decided not to email Alexandra and resolved to stay out of their business, but as I worked the narrative constantly led me back to Alexandra and Homer. Did my brain crave obsession? If so, I couldn’t reasonably think I’d improve matters by involving them in my pathological patterns.

I continued with my routine, piling up the pages, and if I needed some space or missed the sight of other people, I went for long walks at the mall. I was forty minutes into one of them on a Saturday afternoon, my back hurting after hours hunched over spiral notebooks, when I saw Homer heading into the lower level of a department store, his phone hooked on his belt. I tried to ignore him, kept going, but found myself cursing his strutting gait, his obvious indifference to everything around him, headquarters of the world right inside his skull, how lucky for him to be such a person.

I decided to turn back and have a chat with Homer, realizing that without knowing it I’d been looking for him. I could start off with a phony apology for taking up Alexandra’s time at the gallery and for arousing his concern. I was sorry if I’d been inconsiderate of his feelings, I’d say, and regretted any difficulty I might have caused. It made me sick to think of this loathsome display of insincerity and I couldn’t begin to imagine how he might receive it, but if he didn’t accept my apology and became agitated I’d be under no obligation to be civil to him. If his voice got loud and he poked me with his finger or tried to tell me off, his eyeballs protruding with bulging anger yearning to find a way out, I couldn’t be blamed for taking up for myself, a time-honored principle of human interaction. Homer was considerably younger than I was and I had a sore knee and a hip that could benefit from surgery, but I still had enough juice left to step up if the little shit chose to disrespect me. In view of his line of work he should be healing people, not pushing his wife around or stirring up conflict and animosity. Did he think his profession gave him special rights, exclusions from the rules of behavior that applied to the rest of us?

I saw him at a sale table, as nondescript as ever, thumbing through stacks of trousers. He sensed me nearing and cocked his head.

Is that you, Homer?

He squinted at me with annoyance and then looked behind him. No one was there.

Who the hell is Homer? he asked. For that matter, who the hell are you?

My mistake, I said.

I made my escape as fast as I could. The unidentified shopper had no interest in hearing a superfluous explanation, and his breath was so bad that I wanted to don one of those plastic suits scientists wore when handling toxic materials. I couldn’t think of a more perfect person to make me feel like an idiot for mistaking him for someone else. All my raving about Homer and what would happen if he didn’t accept my ludicrous apology had been nothing but delusional drivel.

And though I fled the scene I couldn’t get away from the humiliating thought that I habitually devoted excessive time and effort to becoming a bigger and better fool. I resumed my walk at a reckless pace, the background mall music a blur, the shapes of others shifting in every direction. I needed to control my breath, control my breath, calm down the lurching, rumbling animal, all too aware that it would be with me wherever I went. I should leave the mall, get home and back to work, before I spotted another phantom Homer, subconsciously egging myself on with some melodramatic fantasy of rescuing Alexandra from a dark hidden room off a tortuous hallway, risking further episodes of mistaken identity, one of which would no doubt be my own. The unclouded truth was staring me down. I couldn’t look at people without injecting my self-generated racket into the picture, and the way I saw others had far more to do with me and my needs than anything to do with them. How could I have failed to halt my inner debate and fully accept this fact? I often didn’t even meet people halfway but invaded them, knocked down walls and painted the ones left standing. Had any of them invited me in? Did I care? Why did I persist in doing this? Was boundless stupidity or insufficient humanity enough to explain it? What less disparaging motive could I unravel? As the man fleetingly known as Homer had asked: Who the hell are you? Did I really want to know? Should I vow to control myself and permanently cease working on my project?

I changed direction, focused on walking out through the door that I’d entered, not far away, only minutes. I could get in my car and lock the doors and wait for my mental fog to subside, all those who happened to be nearby safe from me until I merged with traffic and drove with purpose toward my desk, where, I could already feel it, the relentless onslaught of verbalization would continue.

Issue 7 Contents NEXT: Stephanie Says by Alain Douglas Park

STEPHANIE SAYS by Alain Douglas Park

A woman stands alone in the surf. She’s up to her mid-thighs in the water, warm Gulf of Mexico water, and she can feel the strong undertow of the sea. It pulls her legs and sucks the sand from under her feet. It’s tremendous—this undertow—a force of nature—powerful. But, she’s determined to stand in it. So, she does.

She’s not entirely alone. Her lover is near, standing behind her on the dry sand, holding a bag of beach supplies. She calls for him to come to her and though at first he doesn’t move, eventually, after she throws him a stare, he does. He might be a boyfriend—most would describe him as such—but that sounds too serious for the woman so she says lover, even though they’ve been in each other’s lives for years. It’s okay to say lover, since it’s been off and on. This is what she tells herself.

It’s not really swimming weather. Though warm, the wind is too strong. It whips the dry sand, sprays saltwater on her body, and plasters her short hair to the side of her head, molding it like a swim cap. The gulls sail around her without moving forward, hovering close to the ground, wings expanded in the constant breeze.

She walks deeper in, letting her fingertips trail on the water which is murky, browned with swirling sand.

They came from out West, or rather she did, from Los Angeles. He’s in New York now, an emerging actor, though if he hasn’t emerged by now, pushing into his mid-thirties, she knows he never will. She could have helped him at one point since she’s a little older than he and more experienced and it’s her business too—not acting, but getting actors to do what they do, getting, in fact, all those involved in the process to do what they do. And do it right. And on time and on budget. She produces. More than anyone else, she makes it happen.

They’d met up in Galveston (“in the middle,” she had said) because she wanted to look at the sea wall there first—a movie idea that’s been rolling around in her head ever since hurricane Katrina hit, then Rita, a period drama about the devastating one from 1900; a timely retelling to show people what real suffering looks like. And so she stood on the wall and took it in, felt its strength and the seas’ and she knew her idea was solid. She also knew she’d have to wait for another storm to hit (and hit hard) before she could pitch the idea for real. Though that would only be a matter of time.

Then they drove the full length of the Gulf Coast—her driving the entire way because that’s what she does—through the swamps of Louisiana, that endless elevated highway, and then lonely New Orleans, and onward to this panhandle town in the pit of Florida. She picked it precisely because it is on the panhandle and small and unassuming and would likely be deserted this time of year.

This is supposed to be a vacation, a getaway in between projects. It’s the off-season, the middle of October but still pleasant enough. And she likes him enough; he’s familiar (had been one of many at one time), which she’s fine with, since she doesn’t feel like trying all that hard right now. The town is deserted, like she thought it would be. There’re even fewer people than she expected. At first, she’d thought that maybe Katrina was still lingering here—or Rita or BP: Florida gets a little of all of it don’t they—but after the first hour, she could tell that the town has been like this for a long time. It’s kind of dumpy. They stay in a motel.

In the surf, wading against the undertow, she is already badly burned, cooked while sun tanning on the beach without any sunscreen. He, her lover, had forgotten the lotion at the motel and she made him go back to fetch it. He had forgotten her new two-piece as well, and, in the meantime, while waiting for the suit and lotion on the empty beach, she had taken off her clothes down to her bra and panties and sunbathed that way. The burn has put a floral print pattern on her breasts from her lace bra, two little arcs of flowers. That night, sitting on the bed in the motel room, she will think it’s kind of pretty, but it also hurts like shit and she will blame him for it and make him go from store to store, looking for the right kind of aloe.

She doesn’t respect him very much. She thinks he’s a pushover. She thinks he’s weak.

She says this a lot. People are weak. It’s her wisdom, what she’s learned, a phrase which she deploys like shooting rain over the people who work for her, over others whom she takes to bed, and over him.

So why is she with him? It’s not money, even though he has it; he’s had the semi-luck of a semi-talented man, but in the end she has much more of all three: money, luck, and talent. It’s not intellectual either. He’s not dumb per se, but she knows that she is much, much smarter than him. He’s creative; there’s that, but he is by no means brilliant. He is, on the other hand, very attractive and she loves men. He’s a good lover. More importantly, she knows that she can make him do things. Anything she wants. This is why she’s with him, has been for so long, off and on. This is what she tells herself.

Almost every single boyfriend she has ever had has brought up that one Velvet Underground song, Stephanie Says, the one with her namesake being compared to Alaska. And every one—which includes this near-successful, near-talented, malleable, yet good-looking man—gets her same flat stare, the same, really, wow, you know, you’re the first one to make that connection. I’m cold too? You must be a fucking genius.

She has no problem treating people this way. Because she has always been very honest and upfront about herself with others, and if someone still wants to be with her knowing full well how and what she is, well then, she immediately loses respect for them. They are like pets coming back to an abusive master. Morons. Idiots. They deserve whatever she doles out.

As she sits with him in the motel bed, late at night watching TV, flipping through the channels, she can feel her body radiating heat. Her burn is intense. She’s naked because of it, stripped down with no covers because everything that touches her scorches. She flips the channels quickly, the room darkened briefly between screens. Eventually she comes to one of her own shows, one that she has produced, and even though she’s not particularly proud of this one, it does make money like a garbage dump. She puts down the controller and proceeds to apply and reapply the aloe carefully, smoothing wide slicks of it on her arms and thighs, across her flowery chest. She has a glass of ice water by the bed which she drinks from occasionally, small, cool sips, and the cold water seems to instantly soak into her, gone forever once it passes her chapped lips. She looks at him lying next to her in the TV light, prone and relaxed in his grey striped boxers. She looks at him staring at the TV, just watching, comfortable and very much unburned as her show fades to commercial. She takes her glass from the nightstand and holds the cold water above his beautiful bare chest. She smirks at him. She says to him, “How tempting, what would you do, I mean, really, what could you do?” She likes to push this pushover.

Then, this lover, this man she has spent countless meals with, traveled with, lived with briefly on occasion, fucked in every manner possible, directed according to her will, bossed around, dominated, this man looks at her calmly and says right to her face that she should really stop confusing someone being weak with someone being nice. And his eyes don’t flicker a single millimeter when he says it. She is the one who looks away first.

This throws her. She withdraws her glass. She’s off kilter for the rest of the night. Sips her water slowly. Watches her terrible show in silence. Her body is burning and she can’t use it against him to right the balance of power, distract herself from his comment. It was different than anything he had said before. She sensed something different in his voice, a line drawn in the sand. But why now? Why here? What had changed in him? Or, was it even him at all?

She remains off kilter into the next day—awakens to it after sleeping in, her sunburn and her racing mind having kept her up most of the night. Her skin in the late morning air is dried and crinkled fire when she moves; even a cold shower seems impossible—although she does it anyway, and then stays in it for a long time. On the beach the day before she had decided that she wanted to eat at a pier she had seen in the distance. When she’s finally ready, finally through her routine, it’s mid-afternoon and they begin the long walk towards the pier. It is while walking with this man on the beach towards that pier that she starts to think of him and all their time together, all their years spent mutually or tangentially. Replaying all their past interactions as they walk. Moments, instances she thought she had controlled but which now, with every gritted step, become increasingly unclear to her.

The day before, wading in the surf, the undertow tremendous, she was so determined to stand in it. She’d called him over to join her from the shore where he was. But he hadn’t come. She’d called to him again and again, come here, come on, again, come here, and finally, eventually, he did come. And she’d thought at the time that somehow this meant she had won. Had won.

I want to eat here, okay—had won; no, not here, take me somewhere else, okay—won again; now get the check—won; and take me home—won; and take off your clothes and get your ass on the floor, I’m tying you up—won.

These previous thoughts now seem incredibly trivial to her. Presumptuous. He might have acquiesced for any number of reasons. On any number of occasions. As she slowly walks with him through the sand, dangling shoes in hand, she becomes more and more embarrassed by her past actions. She starts to see this man, with his pale eyes, his graceful tapered hands, as some form of saint for being with her. A good man. And she starts to see herself as some form of corrupting evil for being with him, for exposing the goodness that is him to the corroding influence that is her—the idea making her think that she might just be what she has never truly believed herself to be: A bad person.

There are crabs all over the beach. Little zigzagging darts of movement. She is startled and jumps at their incursions. She even moves to him for support, for some weird form of protection. A line of footprint divots converges in the surf behind them.

She starts to remember stories he’s told her, from his life, his childhood. Stories she thought at the time were tedious. She remembers him as a kid on another beach collecting burrowing crabs in his little hands. They tickled his palms as they tried to escape. She never offered a real reaction to this story or to any of the many he’s told. Not one meaningful comment. She thinks there must be pages of responses somewhere out there. Responses that she should have given.

She stops walking. He continues on alone without her for a pace or two, before turning to the sea. She looks at him standing there by himself, white shirt billowing, face aglow, squinting at the dipping sun. They’ve been walking a long time. She thinks, admits, that he looks very strong, squinting that way in the light, as if he is facing the struggles and limits of his career and his age and himself and is doing it graciously and with pride. She thinks of his face, the clean angles, the scratch of his unshaved cheek, the boy softness of his mouth. She thinks of how she never talks to him in the present, asks him how he is, or what else might be happening in his life. She opens her mouth to do so now but nothing comes. She wants to say so much but she has no idea how to organize the words.

She sees then how all of these acts of love, with him and every other person she’s been with, or moved away from, dumped on, every other person she’s used, conquered, bested, and left, how all these things have soaked her straight through, unnoticed. She feels flimsy and useless like a wet paper napkin. The inside of her chest aches, physically hurts, like nothing she’s ever felt before, and then, finally, after all this time, and beyond all reason, for some stupid fucking cosmic purpose, it cracks and she becomes human, compassionate, affected by her lover—she’ll say it: her boyfriend—of so many years, finally matched up in synch with him. Standing on the beach in a crystalline moment.

Now, this is the moment when you have to trust her, the her that is her, the producer, the leader, the bossy girl from the playground, the manipulator of men and women and audiences alike, that coaxer of heartstrings. So please, just do it. And pay attention. It’s very important:

Did she reach all these conclusions just like this, just like she says it happened, all on her own, standing on the beach with him in this beautiful moment? Did her feet rest in sand and her eyes on him when she had these life altering realizations?

You know her. Was it there? It’s a simple question. Was it there?

Well, if not there in that exact spot, in that exact way, then surely it was close to that, maybe after their meal on the way back to the car, before they started driving to the motel. She should be allowed a little poetic leeway. The parking lot sounds nice too, the sun just set, orange glow fading, walking hand in hand. She would take that. It could have been there. She could have done it. Made the leap.

But you do know her after all. So then, her doubting friends and lovers, please, if you would: Did she at least realize all these things before they got in the car, before they started driving back, before they crossed that intersection and were hit by the drunk running the red light? Did she at least realize it all before they flipped and landed upside down? Before they stopped spinning? Before all the scraping metal and splintered glass went silent? Please, if you could, because she’d really like to know what you think. She values your opinion on this, even if she might not want to hear it.

Nothing yet?

Well then, she would insist on going further. Another step into the water. Was it in the very least—this last, most important very least—before she looked at him hanging broken beside her, before she heard his wet breathing slow, before she saw his eyes, those beautiful pale eyes, so glossy, then still, only inches from her own? Well, what do you say? Did she realize it all before it was too late?

Or…

Was it after? Days after. Weeks after. Months after.

She will say it was before.

Just like she says it happened. Back on the beach.

It was before.

And for all those idiots who love her, either then or now, she would say to them that she now vows to never create another one of you for the rest of her life.

That the only reason she’s still even here, that she hasn’t walked into the ocean herself to join the undertow, is that while she did finally realize that she cared for this man—cares for him more now even after the fact; after he’s gone—he wasn’t the one she loved most.

For that she has to go way back, which she’ll do to survive, back to the only boyfriend who never brought up the Velvet Underground song. He was from Alaska. And she’s sure he still lives there. She’s sure at least he’s still used to the cold.

And who knows, maybe, if she ever stops moving, she’ll drop him a line, somewhere out there, at one point. It would have to be a very small line with no details. She does have her principles and when she makes a decision she sticks with it. Maybe just a postcard with nothing on it, or a photograph of some vista she might see and think he might like. She reserves the right to do this.

To all the others, lovers and friends, all those who have played with her, she wishes them well. Really, she does. She wishes them the best. Good luck. She hopes you succeed. She hopes you survive.

Issue 7 Contents NEXT: Two Americas, Two Poetics by Kate DeBolt

The Burning by Peace Adzo Medie

The potholes in the road were filled with muddy water because it had rained the night before. Some of the holes, jagged around the edges, were the size of miniature craters and every time we reached one, we stomped our feet in it and sloshed the brown water on each other. We roared in excitement, our voices pummeling the cool and heavy morning air, as the water splashed on our clothes and skins. It was as if the dirty liquid were seeping into our bodies and energizing us for the task at hand. We were on our way to burn a thief.

We were partly shoving and partly dragging him along with us, hands under each armpit to keep his shaved head and muscled torso upright. At first, when we’d caught him hiding under the carpenter’s workbench with Auntie Naa’s smartphone stashed precariously in his boxers, he’d played stubborn, locking his arms around a leg of the bench when we’d tried to pull him out by his waistband. But a head-twisting slap had left him dazed and pliant. We’d hoisted him to his feet and stripped him of his tools, a screwdriver and a knife with a curved, glinting blade, similar to the ones the butchers used to slice through singed goat hides in the market. After that we’d yanked off his jean trousers, causing him to trip over his callused feet, and fall, and ripped off his t-shirt to reveal the crisscross of smooth, raised scars that decorated the entirety of his back; the man was obviously a career criminal. A bottle of kerosene and a box of matches were not hard to find.

“I beg you in Jesus’ name,” he’d started to cry when we began shoving and dragging him, head lowered, in our midst as we jogged down the main road. We’d ignored his pleas. Jesus himself, in all of his white glory, would have had to come down to rescue this guy. We’d caught others like him before but had let them go after a simple beating with our shoes and belts. Big mistake. They had returned with reinforcements while we slept, broken into our homes, tied us up and struck us with the blades of their machetes and the butts of their locally-manufactured pistols, and taken all that we’d toiled for and cherished the most. At least once a month, we woke up to find that a family in our neighborhood had been beaten and robbed. Two weeks before, armed robbers had shot Mr. Francis, who worked at the passport office, in both hands because he’d refused to tell them where he’d hidden his laptop. They preyed on our mothers who traded in the market and had to wake up while the sky was still gray to meet with the middlemen who supplied them with yams and tomatoes from the north and cassava and okro from the south. These criminals grabbed them while they waited for the buses, which ran infrequently during the early hours, slapped them until their faces ballooned, and stole the monies that they hid in the shorts they wore underneath their cloths. Lately, these animals had begun tearing off these shorts and raping our poor mothers! Right there in the open! Why couldn’t they just take the money and leave?

And we weren’t even rich people. Small Frankfurt, our neighborhood on the outskirts of Accra, consisted of two and three-bedroom bungalows haphazardly thrown together so that street names and house numbers would not make sense if they were ever introduced. Ours was one of those communities where most homeowners had not painted their houses and were comfortable with the grayness of the cement blocks. Cement blocks on which city workers frequently scrawled in red paint: REMOVE BY ORDER OF THE ACCRA METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY. If only the Assembly cared as much about the state of our roads. All but the main road were un-tarred and the red dust that was whipped up by cars coated us and everything we owned. When we washed ourselves in the evenings, the water that spiraled down our drains was red. Not that we could afford to bathe every time we scratched our skins and saw the grime that accumulated underneath our fingernails. The water pipes had not yet reached us–and seemed like they never would–so most of us were buying water by the barrel from the dented water tankers that lined up on the side of the main road like the UN convoys that we watched on TV, driving into warzones. We were, therefore, stingy with the water in our drums and buckets. Not like those people who lived in neighborhoods like Kponano and Alistair. Those people who watered their expansive green lawns at noon when the sun was highest and had large flat screen TVs in their pristine villas and small flat screen TVs in their gleaming cars. People whose homes were littered with the things that robbers sought; the kinds of things that we barely had.

We neared the open field where we planned to burn him. There was a large mound of trash at the east end of that dusty tract of land, a putrid collection of the degradable and the non-degradable. We picked up speed, our feet rhythmically pounding the pavement like a police battalion marching against protestors. In fact, we were speeding up because of the police. We were sure that someone would have called them by now; they would fire bullets into the sky to disperse us if they showed up. The thief would be rescued, held for a few weeks, and released back onto the streets to terrorize us. We weren’t going to let that happen.

There were many others who wanted to stop us. Word of the thief’s capture and of our plan to necklace him had spread quickly. People, mainly women, had lined the road while others ran behind us. They still had on their sleeping clothes; the women with their cloths tied around their chests and their hair gathered in hairnets. Toothbrushes and chewing sticks poked out of many mouths.

“This man has a mother somewhere o, you cannot do this,” Auntie Naa was screaming from somewhere behind us. You would think that she would have been grateful that we’d retrieved her phone and were about to punish the thief who had stolen it. That we were about to send a strong warning to others who refused to work and, instead, chose to use our community as an ATM. Another woman began to ululate. In between the piercing cries she shouted, “Come and see o, our youths are about to kill somebody’s son.” Annoyed, we began a protest chant that immediately drowned her out.

Weee no go gree

We no go gree

We no go gree

Weee no go gree

“We will not agree!” we sang. We clapped our hands and stomped our feet harder. The surface of the un-tarred road onto which we’d branched was too damp to produce dust. Instead clods off dirt flew into the air around our feet and stung those whose legs were uncovered. Not like we felt the pain. The chant had thrown us into a frenzy. We’d become encased in a bubble, generated by our lungs, that blocked out any sound that wasn’t produced by us. We were one clapping, singing, stomping body, pulsing with our determination to avenge what those criminals had done to us. This one, who was stupid enough to strike at dawn when some of us were awake and alert enough to begin the chase as soon as Auntie Naa raised the alarm, would pay the debt that his brothers owed. It seemed like he’d resigned himself to his fate and had stopped crying out the name of his Jesus. Or maybe he hadn’t stopped, but how were we supposed to know that, enclosed in our bubble like we were?

As we stepped onto the field, we were approached by about twelve of the older men who were not with us. They’d come to rescue the thief. We immediately formed a circle around him. They might have invaded our ring of sound but we dared them to break through our solid wall of flesh. They threw their bodies at our barricade but we held strong and surged forward. They stumbled and fell at our feet. We would have trampled them if they weren’t our fathers, uncles, and older brothers. We marked time until they got to their feet and began to stagger away, defeated.

We threw the thief onto the edge of the trash heap so that his head was cushioned by rotten bananas and cow entrails while his legs lay on the red dirt. We pulled a frayed tire from a ledge of waste above his head and formed a semicircle around him. It was time. He was now frantically searching our faces and boring through our eyes with his. His eyes were watery. We became still. Our throats closed up and our sound bubble began to rise and float away without us.

“God will not forgive you, don’t do this,” we heard one of the women shout.

“Why won’t the men stop them?” someone else cried.

Their voices were intruding on us, breaking our concentration. We had to act quickly. We lifted his shoulder and put the tire around his neck. He was whimpering. He cupped both hands and began slapping them together. The fool thought he could beg his way out of this. As if he and his friends listened when our mothers pleaded with them at the bus stop in the dark. We poured the kerosene over the length of his body. Some of it splashed on our legs and we drew back, our chests heaving. We were struggling to breathe; there was no air, only the stench of kerosene and garbage. The thief, on the other hand, was breathing just fine. He began struggling to stand up, as if the kerosene had ignited his desire to live. The tire around his neck made his efforts clumsy, almost comical. We jabbed our feet into his legs and thrust him back down onto the trash. He started doing the thing with his eyes again, looking at me as if he was trying to escape from his body into mine, through my eye sockets. My palms became slick with sweat. My hands stiffened and I felt that if I wriggled my fingers, they would break with a loud clack. This had never happened to me before. Even when I dissected a frog in the lab for the first time, when I made a vertical incision down its abdomen with my scalpel and pulled apart both glossy flabs to reveal the dark brown of its large intestine and the pale pink of its small intestine. My hands had been steady, flexible. But now, my wet and stiff fingers caused the matchbox to slip and fall.

“Pick it up,” Henry said to me. The matchbox had landed near my right foot. It was touching my big toe.

Why should I be the one to pick it up, weren’t we all standing there? And who was he to tell me what to do?

“Priscilla, stop wasting time and pick the thing up,” Kweku said. We were standing pressed so close together that I could feel his sweat on my arm. I turned my head and glared at him.