SPA CARE by Xenia Taiga

The spa was located in the hills, behind the town’s famous billboards.

“The farthest spot on known earth,” her husband said, looking over the brochures. “No fast foods for miles.”

Her husband helped her pack, while she stood to the side eating Dorito’s. The afternoon sun shone on her as she got in the car and slammed the door. Her husband waved. When she pulled out of the driveway, he called out to her. “Relax enough, so you can ovulate and then we can get back to business.”

The drive took an hour. The spa was a large white building with the mountain behind, hugging it. On the right side was a pool. On the left side was a room with bay windows overlooking the coast. In the middle, as she pushed through the revolving doors was the entrance and a table set up of fresh organic food and juices.

The women in white coats smiled and their voices sang like angels on acid, welcoming her to an experience that’ll transform her.

“Listen to your body,” they said as they showed her to her room. Her room held large windows that faced the mountain. The pine trees pressed against the glass, bits of sunshine filtered in.

She asked for coffee.

They looked at each other. “Why do you need coffee?”

“Because I’m tired.”

They smiled. “If you’re tired, then go to bed or rest in the sauna or go for a swim in the pool, perhaps.”

As she swam in the hot pool, swimming one lap after another, she could hear the wolves howling. She slept that night, hearing them whimpering and scratching her window.

Early morning, they gathered in the great room, prepping themselves for yoga. While they stretched and cried out to Mother Nature, she asked if anyone else was concerned about the wolves. Did the wolves ever pose a problem?

“Don’t listen to the wolves,” they told her. “Listen to your body.”

“But doesn’t anybody else hear the wolves?” She looked around at the other women in the room. Their eyes closed, deep in thought, deep in breathing; inhaling and exhaling.

The lady stood up and walked to her, placing her hands on her shoulders. “What is it your body’s saying? Listen deeply. What is it your body’s telling you?”

“I don’t know.”

“Then on to the dogwood pose, shall we? On the count of three…”

On the third day, she asked for coffee. “Why do you need coffee?”

“I’m tired. I got a headache. It’s a caffeine withdrawal headache. I know it.”

“Don’t listen to your brain. That’s your brain talking. Listen to your body. What is your body telling you?”

“It’s telling me it wants coffee.”

They smiled. “No, it isn’t.”

At the five o’clock spiritual exercise, she stayed in her room. They came into her room, concerned. “I just don’t feel like it,” she said as she filed her nails and cut them into tiny perfect curves.

They gently took the items out of her hands. “Take a rest. Remember why you came here. You came to rest. You’re doing too much. What is your body telling you?”

She asked for a shaver. Her hair was growing back from the last wax and the shaver she brought had already turned rusty. They took the rusty shaver from her, threw it into the bin. “You don’t need to worry about things like that. That is not important. What is important is your body. What is your body saying?”

She sat on her bed’s clean white sheets, watching her nails grow long, curling inward. She watched the short bristled hairs on her legs grow. She gathered the tangled hairs on her head and twisted them up into a messy bun.

That night, it thundered. The wolves howled. The power and lights flicked off. They gave them candles and told them to rest, to call out to Mother Nature and to listen to the body. “What is it that your body is trying to say to you?” they asked, looking into her eyes.

She moved the dresser in front of the door and threw the heavy white candles thick as bricks through the windows. The glass shattered. The rain came in, filling the room. The pine trees tumbled forward, touching her feet.

The mice came, crawling up her body. Sparrows flew in. Together they poked and pecked into her tall matted hair that sat atop her head like a wobbly castle. She laid on the bed and opened her legs. The rabbits wet and white came into her vagina, burrowing and digging to keep warm. The wolves pranced in on tiptoes. They stepped over her body; stepped over the mice, rabbits, sparrows, and came to her neck. They snarled, exposing large teeth. They leaned forward, biting deep into her neck.

The women were outside, pounding on the door: “Listen to your body. What is it telling you? What is your body trying to say to you?”

She closed her eyes and listened.

Back to Table of Contents

ROSA by Anne Germanacos

Just a name

Rosa, a girl in a story, a name I happen to like. She’s a girl with a father who follows her to the ends of the earth as she follows a story, a myth, an incantation.

She is trying to be a virgin and a diplomat, like Gertrude Bell.

She would also like to be a mad heroine, like Isabelle Eberhardt.

Her parents would like her to finish her homework.

Accoutrements

She covets the gypsy’s wide skirt, the nun’s collar, her mother’s braid.

Arrival

She rides up on a horse, plants her bloody hand on the wall of a church, makes her mark.

In the street, she breathes polluted air, lets her father, a man, buy her a drink made of almonds. Says merhaba, says teshekur ederim, turns away from her father. Wants a boy. Wants a penis.

Experiences a moment of 21st century doubt.

The blind doctor

She leans forward in her chair. Can he feel her movement?

She leans, examining him, sees waves break over his gentle face.

She sees him but he can’t see her.

She trusts his x-ray vision, a function of his heart.

Tells him what she wants: a boy, a penis, (a heart).

Naked

Her mother in a braid, her mother in pigtails.

Her brother, a genius or a fool.

They’re all fools.

She twirls in her skirt, her hands tilted toward god.

Naked beneath her skirt, she is breezy.

Questions

What would Gertrude Bell say?

Isabelle Eberhardt, where are you?

*

What does Rosa know about Gertrude Bell?

That she was a highly accomplished virgin, an adventuress, (never an adulteress), a linguist, a diplomat.

Bedouin boys

She’s in the desert, immaculate and alone:

She walks white sand until it’s in her throat and lungs. Coughs sand like granulated sugar, can’t stop rubbing her eyes.

The Bedouin boys appear and dance the depth-negating dunes.

Their bodies are short, wiry, powerful. (She realizes a new incarnation of her own every hour.)

In the almost-cold dawn, they offer her the thinnest version of bread she’s ever eaten, just-baked over hot stones. She takes the bread, aiming for diplomatic distance, can’t help but offer them a glimpse of her eyes, which sparkle.

Her head is covered in yards of white linen.

His heart, his eyes

The blind doctor leans; Rosa watches interest arrive on his face.

His heart is oval-shaped, with honeycomb compartments, each containing a patient, a little like her. She’s young; she lives on the bottom floor. (There’s an old man with a hack who lives above.)

She wants to touch his blind eyes.

Isabelle Eberhardt would do it; Gertrude Bell would not.

Timing

One of these days. In the meantime, bide your time.

(Isabelle Eberhardt is another type of desert woman entirely.)

Her notes:

Forgive my violent emotional weather!

If I’d travelled dressed as a man!

The land and I are one; one with the land.

Call me ……

Does the body answer to the soul?

That hero is long dead, but I’ve read the book.

Not sure I fully understand about soul, but bliss, I do.

I would not convert to Islam.

I do not have six languages at the tip of my tongue.

Refuse to go back to your civilization.

Is this confusion or wisdom, Dad?

This good horse, these camels.

Her life now, as I read it, is finished, closed. But her life as she wrote it is unfinished.

Let me have my unfinished life.

Freak or trouble-maker?

Where are the Bedouin boys?

Truth: layered

The blind therapist creates a gaze through modulation of voice . Without the distraction of sight, he tends not to be deceived.

His theory of truth: that it’s layered. He has a range of stylized sounds that act as his eyes and offer solace or neutrality.

Rosa, speaking:

Parker Williams, a boy in the ring.

I’ve caught a live bird in the hand.

Have you ever been to the Sahara? Walked a desert? Ridden a camel? Known anyone who’s worn a veil, died old, still a virgin?

Are these the wrong kinds of questions to be asking?

*

(What do you see?)

What is a genius?

He is silent.

All-seeing brilliance?

Rosa hides her smile behind her hand, unnecessarily.

She sees orange and red, the greens and yellows of fall harvest pumpkins: something from her childhood, intruding.

Her doctor can’t see. Does that mean he has no brilliance?

–Where are you now?

Like a window, he always knows when to ask.

Rosa wishes she were a doorman, but without having to open and close.

She wants to travel across the desert on a camel.

Her father could come and retrieve her, if he dared.

Her mother and brother would stay home, banned.

She watches the blind doctor navigate the glass of water; she watches the level of the liquid against clear glass.

She shifts in her chair, pretzels her legs beneath her.

She covets the bull’s-eye of genius but would be satisfied to look behind the doctor’s eyes, to see what he sees.

Would she trade her allegiance to the idea of Gertrude Bell for the talents of a Macedonian firewalker? Will she ever lose her virginity? (Is it negotiable?)

She has a friend who eats only white things.

She is unpoked, buttoned-up, all-one. A miserable donut (no hole). Without being punctured, how can she know her center?

His ears

When certain cars pass in the street, he is forced to lean in toward the patient and focus more intently to catch what is being said.

He is all ears.

The pores of the walls open, listening.

The layers of sound divide—he zeroes in on the layer that speaks to his heart: endless longing.

He leans forward, retreats, collects the room’s sounds in a basket in his head. The sounds run through, leave gold.

The child is running against time, her legs are tied to the moon’s shadow.

Someone presses hard on a horn. It floods the room.

*

She dreams she sees him on the street, walking quickly, with a stick.

She runs and catches him just as he turns into his building: Hi!

He knows her voice, turns toward it.

She leans toward his face, finds his hands on her eyes.

She fills his cups with tears.

Back to Table of Contents

PERSONAL AD #1 (Pairs Only Matter In Poker) by Michael Schmeltzer

After C.D. Wright

I wear garish makeup and make faces in the mirror.

Which reminds me…do you want to hear

my favorite joke?

Two clowns walk into a bar:

one with a sad face, the makeup frown

thick and chalky as a hotdog bun; the other

no face whatsoever.

There never was a happy face.

Let me start over.

There are two expressions we carry like dumbbells

to balance ourselves in public.

People are often

two-faced and falling flat

on both of them. If you look carefully

I always lean to the left.

I love honesty

the way a lazy-eyed child loves playing pirate.

How far sunk do you think

a treasure must be

before we call it buried?

What about desires?

For reasons unknown I often find trouble.

My ex-lover phoned me

after an absence of six weeks, drunk and high on meth.

He always called it “Tina” or “Crystal”

as if a drug could wear jewels

or flaunt a slinky dress.

He added lime to his beer and dubbed it a cocktail.

Ever hear of heterochromia?

For a sucker like me it means exotic.

Plus, he was handsome. He had one

hazel and one blue eye.

They were both beautiful

but I never knew which color to trust.

My problem is whatsoever my right eye sees

my left ignores

so he got away with a lot.

His eyes glittered like Vegas

when all I needed was Branson.

By the end there was nothing left to gamble.

All I wanted then

was to slip a penny over each eye

and watch the world bury him.

Listen to Michael Schmeltzer’s reading below…

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/83795956″ params=”color=ff6600&auto_play=false&show_artwork=false” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Back to Table of Contents

HAGRIDDEN by Jen Julian

They called it a boo hag. It’s what Eva said was haunting her when I got her on the phone six years after I’d left Miskwa. I felt the same way every time I talked to her—nostalgic a little, but hurting with secret embarrassment—and it was always at some odd hour of the night when the city noises kept me up. I always found myself wanting to hear her talk about ghosts and demons. She was still living deep in the bog in her grandma’s old house, but she was no more Gullah than I was, and whiter than French bread. Still, the stories of the Gullah folk burrowed deep in her, and they were stuck in there just as firm as when she was four foot tall and barefooted.

“I don’t want to go to sleep,” Eva said. “See, they all knew what it was when I told them the symptoms.”

They, meaning the Gullah folk, her friends and neighbors, the men and women who came to help her weed her sandy garden in the summertime, boiled seafood in big pots and ate in each other’s yards in big crowds, I’m guessing. They liked Eva, white Catholic girl she was, though they probably thought she was fragile, that she’d crisp like a rose petal on a hot window.

“I have these awful dreams,” she told me. “And I wake up in the morning all achy, with my back on fire. Mrs. Legare says that’s a boo hag, a nightmare spirit. It gets hold of you and it rides your bones all night.”

“At least something is riding your bones.”

“Oh, Jim, hush your mouth,” she said. She laughed, but there were tired pieces to it. “It’s the bad kind of riding, not the good kind.”

I wanted to joke a little more, but she listed off what she’d put together to take care of the boo hag, everything Mrs. Legare had told her she’d need: a glass bottle, a bundle of broom straw, a cork, a needle.

“You stuff the broom straw down into the bottle,” Eva said, “and the boo hag gets distracted ‘cause she has to count it all, every last stick. When you get up the next morning, the boo hag will still be in the bottle counting, and that’s when you stick the needle in so she can’t get out. Mrs. Legare said she’d help me.”

“Eva, you should go to a doctor if you’re hurting in the morning,” I said. “Don’t let them give you voodoo fixes.”

“Jim,” she said. Her voice got weird, like dead leaves breaking. “Doctor don’t know anything about this.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Jim,” she said. “There’s one other thing they said I had to do. Please don’t let this make you sad.”

“I’m already sad. Tell me what the real problem is.”

“Jim,” she said. The fact that she’d said my name three times made me wonder if she trying to secure me in a trance. “The nightmares are always you.”

Eva never was an accusatory person, so it stabbed like a spearhead to hear her say that, to dredge up what she knew wasn’t my fault. I had to leave Miskwa. I told her that plenty times enough. My city was all brick, and my apartment was all brick, and sometimes I’d go out and pull off wisteria and put it in a vase on my table so I could smell it when I walked in. Mysterious wisterious. But it always wilted, and that was how Miskwa was. Try and put it to use and it falls apart. She knew I felt this way.

“Why is it me?” I asked.

“Well,” she said, her voice hushed. “I wanted to tell you that, because I think this has to be the last time I talk to you.”

“This doesn’t make sense,” I said. “You can’t blame me for your dreams.”

“I know,” she said.

“You can’t blame anyone for dreams.”

“I have to go, Jim.”

It was abrupt as it was ridiculous. Once she said this, she told me goodbye, gave me a kiss through the telephone and hung up. I sat on my couch feeling stung and itchy and angry. I was the boo hag; that was basically what she said, and she had to cut me out to get rid of it.

For three days, I tried calling her and the number wouldn’t go through. I let my feelings fester, let those feelings go to work saying hello and goodbye to people and places, hello goodbye coffee shop, hello goodbye parking structure. And I thought for a long time about Eva. And at the end of the week, I packed up my car and drove the nine hours back to Miskwa.

The bog was still as dark and untouched as when I’d left it, the dead railroad tracks still there, the live oaks with the Spanish moss and Mr. Tomlinson’s bookshop on the corner of Main and Redtree, the place where I’d first read all those stories with characters that leave on journeys. The idea of getting out of town had been a seed then, and as I got older, it grew, until it had rooted its tendrils. No matter what wild, scary world you entered into, leaving town was what ambitious young men did when they grew up.

Men who weren’t ambitious ended up like John Flynn, who was working at the front desk of the Bed-n-Breakfast. We’d been friends in high school. I’d sent him a postcard from my vacation in Fresno, and he’d sent me Christmas letters and pictures of his daughter, but we hadn’t kept up much more than that. Still, he recognized me fast as I pulled out my wallet. He stared, stood on his toes, and leaned over the countertop.

“What are those shoes?” he asked. “Those are the ugliest shoes I’ve ever seen.”

“They’re my knock-around shoes,” I said. But that was a lie. They were gray and pink tennis shoes and they had pigeons embroidered on the tongue, and when I found them in a basement space thrift store I looked them up and learned they’d been designed by a famous R&B singer and were worth piles of money. I wore them all the time in defiance. But Flynn’s smile made my ears burn, and I felt ashamed for wearing shoes in defiance.

Flynn was wearing a vest, but he looked good in it. His glasses were rimless and studious-looking, and there was a gold chain in the front pocket, a watch that had undoubtedly been his father’s. I heard its tick tick tick as he wrapped his arms around my shoulders and embraced me, the edge of the countertop digging into my stomach.

“If your folks could see you, God rest ‘em. How much money you making?”

“Enough of it,” I said.

“Why’re you here?” he asked. “How’ve you been?”

“I’ve been fine, considering,” I said. For a moment, I hesitated. Did I tell him about Eva? I had driven for nine hours and had thought of little else, and yet still I had no clear plan for what I would say to her, for how to express what I wanted. What did I want from her? Phone calls, at three in the morning. Stories about Miskwa. It would sound stupid if I said this aloud to Flynn.

Fortunately, he didn’t give me a chance to explain my reasons. He’d already gotten out the log book and was writing my name down.

“How long you staying?”

I hadn’t thought about it. “I don’t know.”

He seemed to sympathize with my bewilderment. “How about I put you down for one night, and then we can work the rest out later.”

“Okay,” I said.

“I’m putting you up with Colonel Pickery.”

“Oh,” I said. Colonel Pickery had been disemboweled by Yankees in 1864. Many war ghosts had their stories sealed in Miskwa.

“Don’t worry. He won’t bite,” Flynn assured me. “He might breathe on your face a little while you’re sleeping.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Good to see you, Flynn.”

I went upstairs to unpack my things. Flynn followed me, though I didn’t realize this until I about-faced and saw his broad-shouldered frame in my bedroom doorway, a Frankenstein’s shadow. I grabbed at my chest.

“I thought you were Colonel Pickery,” I said through my teeth.

“Nope,” he said.

“What?” I said. “Jesus, what is it?”

“My shift’s over in ten. The bar’s right where you left it. Just wanted to let you know.”

I went with Flynn to the bar. Nine hours driving, and a few drinks will sound good to anybody. I felt the pressure of everyone’s eyes on me, knowing me, not knowing me. I had changed a lot. I looked like a gawking out-of-towner in stupid shoes, and I walked behind Flynn as if trusting him to lead me, even though I knew where we were going. Then people started looking closer, and it was “Jim? Jim!” and that was an hour gone, and by the third time this happened it was dark, and I knew I wasn’t going to have time to go over to Eva’s that day.

Flynn and I hugged the bar like it was our child. He played in some of the whiskey he’d spilled.

“You should see my little girl. She is a beanpole.”

“I saw the pictures,” I said. “She’s beautiful.”

“Shit,” he moaned, suddenly recalling something. “I should’ve called the wife.”

“Probably,” I said.

“Ah well. She’ll be just as pissed if I call her now than if I wait and show up later. Another one, Richie. That’s the stuff.”

I had not drunk this much in a long time. My face flamed with love and appreciation for Flynn and his company. It was getting hard to feel self-conscious.

“Flynn, I came here because of Eva,” I said.

Flynn looked at me, one sleepy eye quivering. “Eva?” he said. “Eva?”

“Yes, Eva. We’ve been keeping in touch for years, but she cut it off recently, and I need to talk to her about it.”

Flynn looked straight ahead. “That girl Eva. Really, that girl. I love that girl. I do, but if her gramma was still alive, she’d be shamed.”

“Oh, I don’t think so,” I said.

“I know it. If the devil himself showed up at her house, she’d ask him in for dinner. I’m just sayin’. Not my place to judge her. God’ll judge us all. But I’m just sayin’.”

I could tell that Eva was still a strange bird to everyone in town. It wasn’t that they disliked her. For the most part, it seemed, they felt sorry for her, and a little disappointed in the company she’d chosen after her grandmother passed. I’d heard about how the churchgoing crowd in particular avoided her at the grocery store and watched on with stern, lemon-sucking expressions when she shook her skinny hips at the spring festival dances. They would say they were not racists, that they very much appreciated people of color so long as they behaved at least a little bit like “normal” folk and didn’t partake in backwoods hoodoo. Any pretty young girl like Eva who subscribed to such beliefs should simply know better. Their own children had gone off to school. If they were not wildly successful, they made a little money, but Eva had regressed deeper, drawn in, covered herself over with swamp vines.

“Have you heard how Eva’s been lately?” I asked. “How she’s sleeping?”

“She told you about the boo hag, I’m guessing,” Flynn said. “They say she caught it in a bottle, like a firefly.”

“It worked?” I said.

“People been going over to the house to see it. She’s been fine since. No pain. Sleeps like a dream.”

“You’re sure about this?”

“Sure as I am about anything.”

The alcohol boiled in me. Flynn began making a noise in his throat and was seemingly unaware of it.

“Flynn, come with me to talk to Eva,” I said.

“Uh?”

“I’m thinking ‘bout it now, and I’m worried I’d lose my nerve.”

“That’s why you came back here in the first place, yeah? Nine hours, and you’re too chicken-shit to go by yourself?”

I was ashamed. Flynn spoke the truth, and I knew it. I would have to go and alone.

At two in the morning, Flynn stumbled toward the bus stop. I stumbled toward the bed and breakfast. When I walked up the stairs to my room, my skin went cold and my mind turned into all sharp edges. I felt sure for a minute I’d walked through Colonel Pickery.

Eva stole stories. She’d been that way forever, growing up with her grandmother in the bog. Her parents were dead. My parents were dead. With that fact alone, we had much in common. For three years I lived with her and her grandmother, then later with my aunt in town, who now raised horses in Montana (this had apparently been her greatest dream, as people in Miskwa often dreamed about vast, mountainous places).

I knew Eva and her grandmother had always been well acquainted with the lowcountry people, the soothsayers like Mrs. Legare, the poor drifters who came in from Charleston. Eva loved stories, particularly the Gullah folktales. She’d listen to them, lock them away inside her, claim them as her own.

These weren’t Eva’s stories, and they weren’t even Gullah stories originally. Since she told me about the boo hag, I’d read up on Baba Yaga and the old hags from Europe, archaic, centuries-old monsters. But Eva stole the stories anyway, made them real. She’d tried to steal my story too, keep me here, drink me down to make me a part of her. Because of that, I had always seen Eva as a nymph or demon that would pull me back to Miskwa, a boggy past I would have to shed like a cicada skin. I’d never imagined that she would have to shed me.

When I finally saw the old house, the wisteria had overtaken it. After six years, it had engulfed the front porch and was snaking its way up the chimney, a chokehold of thick vine and sweet blossoms. I ran my hand over Eva’s wind chimes. Soft sound.

She didn’t come to the door when I knocked, so I went around back. There, I found her in the garden.

Eva was still thin and her hair was blonder than I remembered it. She had an eyelet blouse tied in a knot at her belly, and if she stood straight, she would only come up to my shoulders. A pair of gardening gloves swallowed up her hands, and the cucumber vines curled around her feet as she walked, grabbing at her. She went stiff when I called her. Her eyes focused, then grew puzzled, not welcoming and not hateful, but cautious, feral-like. An old girlfriend from town used to hate that, calling girls in romance novels feral, but Eva was feral and barefooted.

“Jim?” she said. “Jim, it’s you?”

“It is,” I said.

I stared her down, from the crown of her head to her dirty ankles, and my organs went like stone. I’d thought about plenty of things to say on the way over there, but I now I found myself hung up on “It is” like a fool. Eva looked down at my shoes.

“Those are nice.”

“No,” I said.

“No?”

“No, they’re hideous,” I corrected her, and I told her about the R&B singer who’d designed them, but she didn’t understand.

“Oh,” she said. She looked around her at the garden. It hurt me that she seemed so uncomfortable. “I’ll get tea,” she said. But when I tried to follow her into the house she spread out her hand against my chest and her fingers sparked against the bone and it hurt.

“No, you—” she said, harshly at first but then recovering with politeness. “You stay out here. You don’t want to see my messy kitchen.”

So I sat on her back porch and waited for her. The place smelled like musk and turpentine, and there were some paintings sitting around: trumpet flowers, crab pots, sunsets on the swamp and such. Eva hadn’t told me she’d picked up painting, but if she had, if they were hers, she’d probably be trying to sell them in town. That kind of stuff would sell here. I didn’t like the paintings and I couldn’t figure out why—normally I’d be endeared by them. Then I heard Eva moving around in her kitchen and I realized I was feeling kind of annoyed with her. She was keeping me out because she didn’t want me to see the boo hag.

She came back out with a bamboo tray of ginger tea.

“Why’re you here?” she asked.

I sipped and winced as the tea burned my tongue. “I wanted to see you. After you hung up, I didn’t like how it ended.”

“That it ended,” she said. “You didn’t like that it ended.”

The correction was cool, no rancor behind it. This bothered me.

“That it ended,” I said.

“You didn’t want it to end,” she said. “What were you getting out of it?”

“I am getting plenty. I’m getting plenty now. I like that I’ve come to see you, that I get to see you. And you haven’t forced me off your property and that’s a good thing. It’s good that we’re talking, that I came back here.”

Eva looked at her hands. She looked toward the paintings. “You came to hear about my dream? Nobody wants to hear about dreams.”

“But I do,” I said. “They say you caught that—thing. The boo hag.”

“I did. It’s on a shelf in there, in the kitchen. But I don’t want you to see it. It’s—” she smiled slightly, maybe the first trace of irony I’d ever seen from her. “It’s pretty ugly.”

We sat apart from each other and an old warm static came up. When we first made love, we were both twelve, and maybe that’s young, but there wasn’t much to do in Miskwa besides sex and storytelling. We did both. It hurt her, but she stayed my girl all through high school, right to the very end. End of the world. Now I could feel my edges tugging; if I let her, she could pull me back in easy, but I wouldn’t let her.

Eva tilted her head and closed her eyes. “Do you remember the night we stole whiskey from Flynn’s freezer? When we drank all the way to the bus stop and we got on, like we were going to go somewhere?”

“I remember. You got sick and passed out.”

“I got sick and passed out,” she said. “But in the dream we’re on the bus, and it goes off the road into the swamp. And we’re sinking, right, we’re sinking? And the water and mud are coming in. And you’re an eel.”

I laughed. I couldn’t help it. Eva gave me a warning look.

“I realize on the bus that you’ve always been an eel,” she went on. “You’ve got—little hands, little wiggly hands. And I knew in the dream that they were eel hands. You slipped into the water and disappeared, and I was still stuck in there drowning. And I remembered, ‘It’s like the time you told me we should go to Memphis together, and I panicked because I was afraid, because I knew I couldn’t swim the roads.’ That’s what I thought—in the dream. Then I’d wake up still feeling drowned.”

When she had finished, I applauded quietly. She stared as if I’d cursed her mother.

“Real heavy symbolism,” I said. “But sometimes an eel is just an eel.”

“You’re not taking this serious. You’re making fun of me.”

“No,” I said, laughing. “No, honey. It’s serious, I know.”

“I think you should go.”

“Eva,” I said, leaning forward so that I seemed more serious. “You can’t just push me out. It’s too sudden. You’re the only real tie I have left to this place, the only deep tie.”

“It wasn’t sudden. I’d been telling you for years that it hurt to keep talking to you.”

I could have told her what she said wasn’t true, but honestly, I didn’t remember.

“You didn’t listen,” she whispered. Then she said again, “I think you should go.”

As I looked at her with her little white dress and dirty ankles, I got a strange image of me picking her up over my shoulder and carting her back to my car like a cartoon caveman. Man kidnap woo-man. Man keep woo-man in apartment, drink coffee, shop at basement thrift stores. Then I was laughing again, even though she’d hurt my feelings, and I could feel Eva getting angrier and angrier as we sat there.

“What can I do?” I asked. “I want it to be there still. Our connection. Tell me what I can do, please.”

“Stop begging,” she said. “It’s all sealed up. It’s done.”

She folded her arms, and I hated her so much that I had to laugh at that too. When I returned to Bed-n-Breakfast, I told Flynn I was staying another night.

Under cover of darkness—I’ve always kind of liked that phrase, as if you get to wear the night like it’s a hooded cloak or something—I returned to Eva’s house. From her driveway, I saw that all the lights were out, the wisteria vine protecting everything from the stark moonlight, and the only sounds were the crickets and the quiet clink of the wind chimes. On the porch, I found the key hidden above the lintel, where it had always been, unlocked the door, and went inside.

I trembled as I moved through the house, hoping I was being quiet but it was hard to tell—all I could hear was the thump of my heart in my ears, scary-exciting. At this point, I knew what I wanted from Eva, and I figured out she’d told me how to get it. Maybe she wanted to give it up, some part of her at least, though I knew what I was doing was hateful and selfish, I knew that—maybe city-living does that, or maybe it’s always been in me, the way every place where we live is in us. The inside of Eva’s grandmother’s house had stuck with me especially because those were the grieving and growing years, and I knew every worn patch of shag carpet, the woman’s paisley furniture and linen curtains, the ceramic owl where Eva used to hide cash and cigarettes, brass umbrella stand, amber ashtray, all those precious objects we’d use as our prizes in questing games. So little had changed.

In the kitchen, I saw the boo hag on the windowsill above the sink. There it sat between a pink conch shell and a rag doll Eva’s grandmother had sewn for her. I took the bottle and held it up to the moonlight.

The thing inside, half-hidden in its bundle of straw, was gray and stiff, shriveled to the point where you could make out the bony limbs and body, but not the face, which had sunken in. Her arms hugged her ribcage. Wisps of yellowish hair, frail as onion skin, clung to her scalp. She was like an old woman, as threatening as a moth pinned to corkboard. As I pinched the needle that held her in, her smushed face flinched. One white eye opened and trailed up to meet mine.

I heard a cry. Eva was there, standing in the kitchen doorway, dressed in a long cotton night shirt.

“Jim, don’t.”

I held the bottle up and shook it a little. “This is it?” I said. “Kind of remarkable, really. Kind of…sweet. I mean that for real, I think it looks sweet.”

“Jim, give it to me,” she said. “Give it to me, please!”

She grabbed my wrist. Around we went like dancing partners and she put up a good fight, but still, I was taller than her. I pulled out the needle. I pulled out the cork. The creature inside uncurled like an insect from its cocoon, twisting, squeezing herself out the bottleneck until she disappearing in the open air. Eva screamed. She searched around for the creature, but she had gone, flitted out the open window to hide in the garden. Eva took the empty bottle from me and smashed it in the sink.

“I hate you,” she said.

“You don’t really,” I said. “Or maybe you do. But you won’t always.”

“I can’t stand it,” she said. Already, she looked far more wretched than she had looked earlier that day, with the sun shining on her white dress.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

I was sorry, for real, but even so I slept good that night. Even with the Colonel Pickery breathing on my neck, I slept like stone. The next morning, I felt very awake and very sober as I drove the nine hours back to the city.

SATURDAYS AT THE PHILHARMONIC by Megan Staffel

Patsy Smith left Rochester, New York on a sunny Saturday morning intending to drive all the way to California. But after three and a half hours, crossing through an Indian reservation, she got lost. On a long, straight road, where there hadn’t been a route number for many miles, there was a sudden break in the forest and she saw a small building with cars and trucks parked in front. She turned in to ask directions.

Pulling the door open, she smelled beer. She saw men with their backs to her sitting at the end of a room on bar stools, and close by, a few small tables and chairs that were mostly empty. The door snapped shut behind her and in the sudden darkness all she could make out were the neon beer signs. She stood still, waiting until her eyes adjusted. It was nineteen sixty-eight. Patsy was sixteen. She had an old car, a hundred dollars, a pillow, a blanket, a pair of broken-in lace-up boots; that was the total of her possessions. But it was all she needed.

The man sitting at the table closest to her was the only one who had seen her come in. He stared at the girl with bare feet, filthy pants, long curly hair, and a wide pale face that even at that moment in a strange place, had an oddly quixotic expression.

Patsy was remembering a fact from seventh grade New York State history. These Indians, the Seneca, were called Keepers of the Western Door. They were protectors. Maybe that was why she had chosen the route that went through their reservation, and now, having lost it, maybe that was why she felt so confident standing in the smoky room.

The men at the bar, a row of dark backs with dark heads, talked quietly. When her eyes adjusted, she saw the man sitting by himself at the closest table. A shaft of light, coming from a small window, settled on his shoulders and made the rest of the room unimportant.

Patsy Smith stayed by the door, covered in shadow, but lit up, inside, by the beam of the lone drinker’s attention. She had left her home in a rush and on this first afternoon that she was on her own, she could already see that when she was away from her family, she, as a separate and independent person, would matter. The man in the light was slowly standing up. He didn’t look at her, but she knew she was the reason he’d gotten to his feet, and not the bathroom or some peppery old geezer sitting at the bar.

“Help you?” he asked.

It was not a friendly face. It was too hard for that. But he looked at her straight on, the raw flat angles of his cheeks glistening.

“Did I miss a turnoff or something? Route seventeen? I think I lost it.”

There was a flicker of amusement at the corners of his mouth and he said very slowly but in a proud tone, “You most certainly did. This is the beginning of the end of everything you could call familiar. So why not stay for awhile?”

Her warning system had been defused long ago. So it didn’t make her nervous to be the only woman in a room of stoop shouldered old men with a younger one who spoke in riddles; in fact, it sent an excited shiver down her spine. She joined him at his table and had a beer. And when he asked her a question, she told him a few things about herself: that she was going to California, that she had major plans, that she didn’t know exactly where in California, but that was only a detail. He told her about Handsome Lake.

“He’s the prophet who saved the Seneca from the white man. His visions restored our people.”

“Handsome Lake,” she repeated, her brain foggy from beer on an empty stomach. “That’s not your name, right, that’s someone else?”

“Someone else.”

“Well I’m Patsy Smith.” She extended her hand, aiming all of her enthusiasm into his dark, simmering eyes.

“Uly Jojockety.” He said it softly and without any salesmanship, but he did offer his hand, and when she took it, she could feel the dry grittiness of his palm and realized how far she was from the land where people with soft palms named Smith ruled over her.

“So who is this Handsome Lake? Does he have a Bible, sort of, or a radio program?”

He laughed. “No, this was long ago, 1799.”

“You’re kidding.” The way he’d spoken she’d thought it was now. “So…how do you know about him?”

“You see, we’re not like you. What we have is a straight line that goes from this day now to his first vision in 1799. The now, the here,” he touched the top of the table, “it rests on what happened before.”

“That’s really far out,” she said, thinking to herself that you might want to remember old Indians, but old white men it was probably better to forget.

Sometime later, she left him to go outside to pee. And while squatting behind the building, her ass visible to anyone who might walk past the row of trash cans, she was startled by a crackle of leaves and looked up. There he was, looming over her, his face more craggy from the ground up. Apparently, a lady’s bare squat didn’t prohibit a man’s gaze.

“No need to be embarrassed. Nothing new about a woman pissing.”

She pulled her jeans upwards, careless about what he might see, and he said, “but girls from Rochester, now I thought they only used toilets.”

She was stung by that word, girls. “Some maybe,” she answered, “not me. I’ve been doing this forever.”

She had her third beer leaning against the trunk of a cottonwood that was as ancient probably as the events he spoke of. He told her about the United States government stealing ten thousand acres of the most fertile Seneca land, river land that had been protected since 1794, in a treaty signed by General George Washington himself, how they’d removed his family and a thousand others. Just to build a dam that could have been built somewheres else. But no, Indian land was their choice. The good people of Pittsburgh, three hundred miles away, needed protection, by the US government, from the inconvenience of high waters in the spring.

“They burnt our house down, cut our trees, gave us a handful of dollars, and stuck us in a little white box with all the modern conveniences we didn’t want. They took it all. No more fish, no more fields, no more forests, no more longhouse. No wait,” he held up a finger, “let me be fair, they moved the longhouse. So then they said, what do you Indians have to gripe about? Okay? What do you Indians have to gripe about? And now do you know what they’re saying? They’re saying, wait and see, we’re going to lay route 17 right through your reservation and cut it in half. You saw how it stopped, right?”

“It just sort of disappeared,” she said. “And then all these little roads you were supposed to follow were really confusing and I got lost.”

“Exactly. That’s because we will not let a foreign government make a highway through our land.” With his hand on his chest, he intoned in a solemn voice, “I pledge allegiance to the Seneca Nation to frustrate the United States Traveler forever and ever.”

She laughed, happy to collude in such vehement anti-establishment feelings.

The sun was sinking. Rays of light were scattered by the leaves that laced the blueness of the afternoon. She knew she was drunk. But only partially was it alcohol. The rest of her euphoria was caused by the situation, the fact that her parents had no idea where she was, that she hadn’t had anything to eat since dinner the night before, and that a man with a kind voice and a long ribbon of hair, a man who was of people who had things worth remembering, was becoming her friend. Just then, his hair was brushing her arm, his full purple lips were parting slightly to ask, “How old are you Patsy Smith?”

“I’m old enough to know what you want. And I’ll tell you something, Handsome Lake, I want it too.” It came out just like that, one whole piece, smooth as something memorized. But she had never before said anything like it. She watched his face, gauging the effect, and then, with the same quiet authority the first violinist in the orchestra lifted the bow and laid it across the strings in preparation to begin the symphony, she raised her arm and set her long, pale-fingered hand on his blue jeaned thigh. Every Saturday of her entire life, her mother had gone to the Rochester Philharmonic. And so it was on that beautiful afternoon she was sitting in the audience, straight-backed and focused, as her daughter, who cared nothing for classical music, was sprawled on the ground a hundred and forty three miles south, orchestrating, with the same drama and promise, slender fingers on a stranger’s thigh.

But the Keeper of the Western Door leaned away. He sat back against the tree trunk and said, “There’s nothing special here. Nothing romantic. What we have is poor land and complicated weather. This is the place, Patsy Smith, where all hopes are destroyed, all expectations are lowered, and every vision of the future is worsened. I’m warning you. Anyone who survives crawls away injured. So do you really know what you’re doing? Because the only thing to recommend me is the before and the here, the this.” He put a lean hand on the ground underneath him. “But not the after. Clear on that?”

She loved the sound of his voice. She could just lie down and listen to that kind of poetry all her born days. Uly Jojockety was a teacher. He would teach her everything she needed to know. She removed her hand from his thigh, unzipped her jeans, and pulled them down, flinging them off with a heroic flourish. Oh, the terrible wrongs that had been done to him and his people!

But then, as his body moved over hers, cutting out the light, there was a moment that dropped out of the progression. She knew she would remember it. It was before anything happened, when she was still a girl from a suburb of Rochester escaping difficulties at home. And then, as those rough hands discovered her, she watched herself become someone else, someone she hadn’t met before, someone who was outspoken, a woman who would be comfortable in her life, who would feel for others. She’d say, sweetheart, honey, baby cakes, announcing her affection for whomever it was she spoke with. That person would take over. She would lead her from one sorry man on the earth to another, moving from Salamanca, New York to Olean, Batavia, Buffalo, always keeping to the clouded western side of the state until she’d had enough of other people’s troubles. The wisdom was hard-earned. And when she was in her fifties, having been through it all — children, booze, narcotics — her body would cease its raging.

But that was the future. It would take thirty-seven years to get there.

Listen to Megan Staffel’s reading of “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” below…

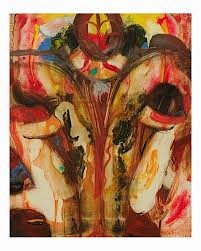

Megan Staffel explains that this untitled painting by Annabeth Marks feels connected to her story because it “expresses female sexual longing.”

LENT by Paul Lisicky

Father Jed’s head was stuck in Lent. He said these words to himself as a kind of talisman. Otherwise, his head would have split in two. He sat on the chancel with Father Benedict, the assistant pastor, up on the priest’s seat. Why was he so torn up on the night of the Easter Vigil? It was the most joyous mass of the year. The choir, the drummers, the brass ensemble, the woodwind players, the readers: everyone had been preparing for this night since the doldrums after Epiphany. The church was dark, completely dark. It gave Father Jed a thrill to think of one of those perpetual latecomers stalled at the vestibule. The dark made things scary. The dark made the first reading, the story of Abraham and Issac, scary. The dark made the second reading, the story of the Red Sea parting, even scarier. What kind of God would exact such a price on humans? Father Jed knew that doubt was acceptable. Doubt was of a piece with faith. You could not have faith without doubt. Faith was active, dynamic, but doubts on the night of the Easter Vigil? It was unseemly, as unseemly as the young men from Our Lady of the Martyrs, who hefted the cross of Good Friday on their shoulders across the Safeway parking lot, knowing full well they were in a Jewish neighborhood. Father Jed couldn’t see any of the faces of the people. Their candles were snuffed out. The Chilean wine palms shadowed the windows from outside, purpled, ghostly. Then the lights went on. Sister Ray was incensing the chancel and transepts, with the bowl she held high, her troop of six dancers behind her. They were leaping, reaching, turning, flashing through the smoke. Their gestures said, Our God is a good God. Our God is a friend to the stranger. The incense stung his eyes. It was so strong in the air that he tasted it on the back of his teeth. Someone coughed. The dance had seemed like a good idea back in February, long before the saguaro had bloomed by the front doors. Dance always had something of risk about it. Maybe this time someone would fuss to Bishop Ren, which was exactly what his parishioners wanted, something to get riled up about. And yet Father Jed wanted to slide down the priest’s seat, cringing in embarrassment for everyone assembled. Had the dancers listened to the readings? Had the people? Apparently not, as everyone facing the sanctuary looked hot with delight. They were so ready to sweep the rigors of deprivation aside. They were so ready to get out of that desert, though most of them had chosen to live in one, air conditioned. It took everything in Father Jed not to leap out of his seat, dash into the sacristy to turn off the lights. What would Sister Ray and her dancers do if they couldn’t see the seats? He imagined the startled gasp, the strangled cry. Now see who your God can be, Father Jed thought. He gripped the arms of the priest’s seat. Had he said those words aloud? He couldn’t tell outer from inner anymore. Oh God, dear God.

By the third reading, God said, “I am taking you back,” and Father Jed felt his eyebrows crisp as the responsorial psalm wended its way toward E minor. What had he been thinking? Had those ghastly thoughts sculpted his face? He looked out at the parishioners he was closest to—Juan Fernando in the second row, Daisy two rows behind Juan Fernando, Dean all the way in the back, face half-concealed behind a column—for reassurance, but none of them looked back. Surely his friends would let him know, these friends who had shared everything with him from their Xanax dependencies, to their breakups, to their bitter little affairs late into the evening as they walked along the arroyo. But none of them looked back at him. They were looking at the feet of Father Ben, which were just slightly off the floor. He was giving the sermon. He was doing his usual, linking Terminator 2 to Flannery O’Connor to one of the psalms, and managing to connect them with bleak, expert joy. Everyone was looking, as if by sheer looking they were keeping his feet in air. Father Benedict did not look down. He did not know what was happening any more than he knew what he was wearing on his feet, one shoe black, one shoe brown. The mismatched shoes didn’t appear to matter to anyone, which might have been why Father Jed got down on his hands and knees and crawled across the carpet toward Father Ben, with his own black shoe in hand.

Listen to Paul Lisicky’s reading of “Lent” below…

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/74715584″ params=”” width=”325″ height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

NEW YORK TO PHILADELPHIA by Lynne Procope

Well I’m not supposed to see you looking

I’m not supposed to stare straight into your eyes… – Lucero

Let’s say Philadelphia’s a city constructed entirely of door knobs,

one great opening, one endless turning into something new.

Your voice is on the phone, love, is a rocks glass overflown

with whiskey and burning. Your thumbs slip from keypad

to six string, your thumbs are the teeth of wild city cats.

I’m only ice. I’m inanimate without your mouth. I’m cracking.

Let’s say New York does me in. This city’s riddled

with pothole metaphor, with stay. These streets are slipping

in upon themselves. Everything is so hungry. My legs

stumble under all this – give in. There was a plain precision

to your hands, and each was a thousand and each owned

a fist of hunger.

I say there was a night we swallowed the city in cobbled slices

we took the city in, one sharp sheet of glass and scaffold at a time

and our drunk breathing and the frost on the sweet gum trees.

Your hands were a thousand and then they were only two.

I was a dozen women or just this one. I was a woman

you were missing. You were all night and all of a day even after

we pulled the city down, even after all the rest of you

was trembling, even after all the rest of you was gone.

LIFT by Muriel Nelson

Doubt seems to be in.

The worry drill whirs

where the dote is.

Where the face was

a vacancy. And yet

the ear is occupied

waiting, for there are

other root canals, so you (mis)heard. No doubt the fire’s hunger whirls

its roar and weather down your

ear while eating sky and licking

daylights off dry trees. Just as

you think you get the picture a

huge sun puts tongues in cheek

and pushes its round belly from

your table. Sets awhile. Your

breath is rising. A tree that you can feel leans toward a mountain. It is

still. The mountains sleep just now. Their dark breasts. You breathe.

In the night above these mountains, the tiny plane your son is flying

lifts. It lifts on air you breathe. It disturbs the air ahead of him and

then the air you think you just breathed out, not him. You breathe.

The phone’s still silent. Breathe.

Listen to Muriel Nelson’s reading of “Lift” below…

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/72726642″ params=”auto_play=false&show_artwork=false&color=b50f18″ width=”325″ height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

SPELL I by Mary Lou Buschi

After Louise Glück

1.

Somewhere, my brother is traveling—

The right side of his head

a red-clawed tulip

swallowing the cold.

2.

Where to look—

down the long expanse of each train car

rocking through a dimly lit tunnel

dark buckling around me

as the car rises up above a city.

When did I last hear my voice?

3.

What was it like?

Fast, bright—tinfoil between my teeth

And then nothing—for a while.

Listen to Mary Lou Buschi’s reading of “Spell I” below…

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/74516961″ params=”” width=”325″ height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Michelle Butler, “Transfiguration” (2012); encaustic on board

Mary Lou Buschi’s poem influenced this encaustic painting by Michelle Butler. The artist explains: “The poem struck me as a moment of transition, so I wanted to represent the push- and pull-forces… beyond our control when we are in transition. The… ominous grey of struggle [is] gently pulled into turquoise — a color that universally symbolizes healing. The movement of the pigment in the wax and layers is evident so you can see and literally feel the journey.”

HOOK ECHOES by Kevin Heaton

Sunshowers spit-shined the shark’s

tooth that gutted Kansas’ only diamondback.

You were just a puff adder feigning rattles—

scavenging rat droppings with field mice

in bales of switchgrass.

I want tallgrass.

I want a thunder god with flashes of ego—

a two-storied sod house near an artesian well—

flag-side-up roses.

Wall clouds that squall more than hook echoes.

I want storms made out of water—rain that doesn’t flinch

at dust—ballsy wheat—flaxen—fully-headed—two fresh

holstein heifers, & slow-churned farm butter.

I want forty ripe acres of Amish maize—two mules,

& a bullmastiff named Shep who eats corn snakes.

I want to break a green feather bed with a Dundee man.

THE DANGERS OF TIME TRAVEL by Gerardo Mena

You wake up in the future and realize that everyone has evolved. People now have the head of a blue jay and the body of a shiny machine that whirs softly as its insides spin. You see two bird heads that look like your parents, but, of course, that is not possible.

When they see you they cry and shake their heads slowly with disappointment because you are not like them. I’m sorry, you say, your voice rough and hard from one thousand years of sleeping. We are all dying, they sing, their voices like glockenspiels.

Below, watch Gerardo Mena’s original video for “The Dangers of Time Travel”…

MOLES by Matthew Haughton

Something had to be done about the moles;

labyrinths stretched from the garden

down to the hollow. Give moles an inch

and they’ll burrow up to your door.

So we dug holes in their paths and filled

them with old coffee cans. Bleary eyed,

dirty noses raised, down in the can

they’d be covered in silt like coal-miners

pulled from a cave-in. If you weren’t cruel,

you carried them over to the woods

to knock them out of the cans. Mad as piss,

they’d shovel off in the light to other pastures.

Listen to Matthew Haughton’s reading of “Moles” below…

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/72455869″ params=”auto_play=false&show_artwork=false&color=b50f18″ width=”325″ height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]