BOY IN A FIELD by Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

Boy in a field understand The lame

Hearted go to him mouth filled

Broken He brings the horses

Of his grandfather His hands wheat

Heavy I have seen him Monster himself

With river-sickness and a girl His mother

Maybe as a girl It is hard to say

Her story Tell it He is afraid The lame

Hurt too Hearts in the coal filled even

The horses’ lungs He will bring them

I have seen him afraid of himself

His river-sickness Bring him

Horses Tell her story The girl broke

His wheat-heart It is hard to say Why

He is afraid Maybe a girl hurt too

Go mouth filled Black lung-wings

He will bring the lame I have seen

Him monster himself I understand

Why Tell him I love Bring him

Listen to Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick’s reading of “Boy in a Field” below…

Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick took this photograph and chose to pair

it with her poem because it embodies “a sense of abandonment and

at the same time, anticipation for things not-yet-lost.”

TOWN OF THE BELOVED by Allison Seay

We rested on a blanket by the water

where I combed the sand and spoke your name gently

You slept but I was not tired and never have I studied

the fullness of a back not even of the dying

propped on their sides as I did yours then

I tried to mimic your breathing though I did not close my eyes

at least not for long instead I kept a kind of vigil

swatting for you what seemed a thousand nameless insects

See it was afternoon the ocean warm to boredom

boat oil and pelicans and I thumbed through a book

while I waited for you to stir to apologize but for what

for disappearing for leaving me to distinguish alone

my desires to want you or want to become you

Wake up please wake so that I might tell how it is

I can for you sit all day in a field of sand

Listen to Allison Seay’s reading of “Town of the Beloved” below…

GOSSIP TOWN by Allison Seay

When Esther is pouting and knows I am bored with her

she asks if I am having one of my Days,

and I say What? meaning no, meaning yes

I am, and she says again and louder, “Are you having

one of your Days” and the word Days is like a string

of beads she pulls from her mouth,

a long accusatory sound (like feign or blame).

We gossip to kill time though she thinks it is only

any good in a town where people hate (as in hate) other people.

For instance, Hazel Hamilton was dead in her house three days

before anyone went to see her, mostly meaning well.

If I had tried, I could have spied her in the wingback

through a slit in the curtain. Sometimes when I have a Day

(as in Hazel) I spend the afternoon in the yard

and imagine her nest of white hair

peeking over the other side of a mouth-high fence,

ivy draping either side to keep in or keep out

whatever needs keeping. Esther reminds me

about being unkind

lest I die alone and unfound in a chair by a window.

It is such an example, she says, and I say of what

and she is in her pouting way on the paint-flecked glider

saying oh

I think you know

as though it is a secret between us

(what secret there are no secrets).

Listen to Allison Seay’s reading of “Gossip Town” below…

CHIMERA by Vievee Francis

I have no charms. Admittedly.

No gold comb can move through

This mane. My skin is not translucent.

It is not soft. Mine is a tail to fear. I know.

But from this goat’s body,

Up from my wood-smoke lungs, from

The milk of me, comes a song, a melody

To open your wounds, then lick them clean.

EPICUREAN by Vievee Francis

A hungry mouth, an empty mouth, insistent mouth,

mouth that would be filled by the seaweed of me,

that would crack the shell with a rock and take

its portion. The mouth gages its slide, gapes—

grotto mouth. Mouth where I might go to pray,

to fall upon my knees before. A mouth full of yes,

singer of heights and sorrows, Swannanoa of

a mouth. French Broad, Pigeon, a mouth so wet,

sweet as a North Carolina river. A mouth that keeps

its secrets like a mountain still. Moonshine mouth,

mouth of fiddles and laments. Yes, a mouth that knows

itself. Generous. No virgin’s pout, nor a greedy boy’s

insistence. Give me one that has been already schooled.

Not excess, but experience.

Epicurus did not advocate for wine,

but for salt of the skin,

and water to quench it. Paradox but not duplicity.

In my awe I would have this honest mouth, dive into the bliss

of it. Speechless mouth that makes its desires plain—

Who wouldn’t want to

draw from this cup the well? Give me a mouth

I might place my own chapped lips to in the heat

of summer. A mouth to sate, to surrender.

GRINGO by Brandon Courtney

Wetback. Fence-jumper. My father’s heart fists

with its yearly dying as he recalls his hired hand—

a Hispanic—burying

our tractor to its axle in a soup of snowmelt

to men who, every morning,

sit half-mooned around the greasy spoon’s table,

lifting Styrofoam cups to sunburnt lips:

hardscrabble farmers—chassis grease

gloving their hands, prove rumors

of neighbors’ gone

belly-up, face down, neighbors fenced-in

by stars. And I’m ten years old, impossibly here,

spit and image of men I’m warned to call sir,

men who’ve bottle-fed

my younger sister as tenderly as their own

daughters and they’re cursing, cursing.

It’s goddamn the weather, goddamn the busted baler,

goddamn the combine’s clutch chewed to shit

then one of the men says I would have shot

the little beaner right where he stood.

Everyone laughs.

I laugh too, although I don’t

know what spick means, beaner,

only that my father is coughing, which means

one more year, two if he’s golden,

which is nothing

to cemetery soil, the patience of the open grave.

The others stay, careless in conversation,

as if their voices were enough

to keep their small, Sunday god

from deafness. Years later, I’d land summer work

at Iowa Beef Packers pressure washing

gore from stalls, as undocumented men worked

blades, quick as flies, on the bloodletting line.

When I ask Eduardo how, lace-deep in rarefied blood,

he could open the soft machines

of bulls with a razor knife, cut away flesh

easy as a winter jacket, he presses his thumb

and index finger together like locust wings

and rubs, which means money,

which means everything.

Not surprising when Eduardo

says his younger sister, unable to speak a lick

of English, would show me her naked chest

for twenty dollars after work,

says she’d already lifted her skirt

for half the slaughterhouse

gringos. She, dressed like a Salvation

Army mannequin, led me behind the dumpsters,

unsnapped a dozen iridescent buttons,

and it was done—that fast.

Afterwards only the graceless,

shopworn cups eclipsed her breasts

that, just moments before, I’d admired

as slow fire, as her necessity’s waning gift.

She’ll never know how I once opened a book

of poems over my father’s headstone

in the blue hour and began to read the words

which sounded more like a prayer

than any prayer, as soil’s sickening

labor turned his body

deftly as erratic stone, his blood greening

blades of cemetery fescue.

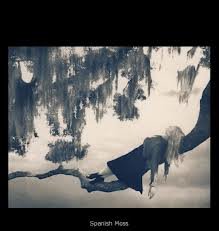

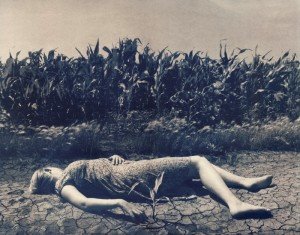

Brandon Courtney’s work is paired with Emma Powell‘s photographs, “Spanish Moss” (above) and “Volunteer Corn” (below). The poet explains that he wanted “Gringo” to appear with these photographs because they embody “the surrealist, quietly violent nature of a rural setting.”

JANUARY by Sara Uribe, translated by Toshiya Kamei

ENERO

en las calles hay testigos que juran haberme visto caminar por ciertos sitios dicen que vivo ahí del otro lado de la palabra que tengo un jardín donde en lugar de flores todas las noches siembro olvido pero no los conozco y no sé si mienten o si la memoria es un rostro un ojo de murmullos que nos sigue y nos acecha cuando los días son más oscuros y la vida apenas comienza

On the above left, listen to the original version of “January”…

Sara Uribe was born in 1978 in Querétaro, Mexico. She is the author of Lo que no imaginas (2004), Palabras más palabras menos (2006), and Nunca quise detener el tiempo (2007). English translations of her poems have appeared in The Bitter Oleander, Harpur Palate, and So to Speak, among others.

JANUARY

on the streets there are witnesses who swear they have seen me walk around certain places they say I live beyond the other side of the word that I have a garden where instead of flowers every night I sow oblivion but I don’t know them and don’t know if they lie or if memory is a face an eye of murmurs that follows us and lies in wait when days are darker and life barely begins

- Published in Issue 2, Poetry, Translation

EDGE by Sara Uribe, translated by Toshiya Kamei

FILO

en el filo del tiempo pronuncio tu nombre una y otra vez como una suerte de conjuro pero todos saben que una palabra pierde sentido si la repites muchas veces que una palabra es demasiado frágil como para no romperse como para no rasgarse con el filo inverso del silencio así que mi voz se desvanece entre los hilos invisibles del sentido y sólo queda en el acero solitario del lenguaje una sombra una traza que se dispersa

On the above left, listen to the original version of “Edge”

Sara Uribe was born in 1978 in Querétaro, Mexico. She is the author of Lo que no imaginas (2004), Palabras más palabras menos (2006), and Nunca quise detener el tiempo (2007). English translations of her poems have appeared in The Bitter Oleander, Harpur Palate, and So to Speak, among others.

EDGE

on the edge of time I chant your name over and over again like a spell but everyone knows a word loses meaning if you repeat it many times a word is too fragile not without breaking not without tearing with the opposite blade of silence so my voice disappears among invisible edges of meaning and what only remains on the solitary steel of language is a shadow a trace that scatters

- Published in Issue 2, Poetry, Translation

ON THE SEPARATION OF ADAM AND EVE by Timothy Liu

It’s unknown when they were first

parted, only that they were painted

on panels by Goltzius circa

1611. Deprived of his companion

in paradise, Adam showed up in 2003

at a French auction and was sold

to a New York dealer, a branch

of hawthorn in our forefather’s hand

clutched to his chest, the bottom edge

of the painting cropped just above

where his nipples would’ve shown—

his life-size figure mirroring back

who we are, sprigs of hawthorn

crowning his curls, all sold in turn

to the Wadsworth Atheneum the following

year. Exactly when Eve showed up

in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Strasbourg

is beside the point. What counts is when

you turn the panels over, the markings

match. Never mind that they were made

for one another, his head turning

to his own left, hers to the right,

offering up an apple to his mouth

if only she could move it from one frame

to the next. Nor will his hand ever touch

her breasts, nipples angled up, her tresses

flowing free. The curator of the Wadsworth

claims it’s been centuries since this pair

was last seen together, other paintings

in their vast collection still searching

for their mates, often victims of scheduling

or financial restraints. Best hurry up

while there’s time—our reunited couple

on view from Feb. 14 to the end of May.

Listen to Timothy Liu’s reading of “On The Separation of Adam and Eve” below…

Timothy Liu’s poem refers to Dutch master Hendrick Goltzius’ panels Adam and Eve, painted in the early 17th century. The paintings were briefly reunited for an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts of Strasbourg in the spring of 2010, after over a century apart. Image courtesy of The Wadsworth Museum.

FIRST MEMORYby Timothy Liu

My mother in a stupor,

stumbling down

the hallway in panties

soaked in blood—

my hand leading her

back to bed.

ANONYMOUS by Timothy Liu

MAKE ME JUMP INTO THE AIR by Cat Richardson

After David Bowie’s “Moonage Daydream”

Listen you’re a moonage marvel,

a Bowie from the Bayou with a snake

in your pant cuff. You carry an electric

swamp around you like a cloak

of wet stars.

Skinny legs, I’ve seen you leap

over cars without a running start.

I’ve seen you become a diving bird.

You dipped into the water and came

up with a flayed goat’s head in your

claws. Picked the flesh off, you did.

Start a fire. I’ll send smoke up

to the smallest gods.

That might not sit right with you,

friend, you’re a complicated

little splinter, but get low with me:

I’m an alligator I’d make fine

leather goods. You’re a space invader

so set me loose in the pulsar’s pool.

Keep your toes sunk in the bog

bottom. It’s the only way

to lose this freak parade—we’ve

got a long way to go before the ground

reaches the sky, and you’re all

I’ve got in this radiant swamp.

Listen to Cat Richardson’s discussion of “Make Me Jump Into the Air” below…