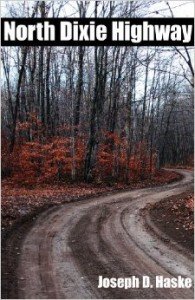

Take Four: An Interview with Joseph Haske

In this installment of “Take Four,” we speak with Issue 4 contributor Joseph D. Haske about narrative structure, blood feuds, drinking, and the pleasures of writing in and about Michigan’s U.P.

FWR: Your novel North Dixie Highway is very much about place, but it seems just as much about time, especially its ability to deepen wounds instead of healing them. It is painful to watch the book’s narrator obsess about killing his grandfather’s murderer, a man who, for very practical reasons, he can never reach. This kind of abiding hatred—this concept of “blood feud”—is often associated with small, rural communities like the novel’s U.P. Do you think that these wounds really do run deeper there, or is the distinction just a cultural fantasy?

JDH: Based on my experience living in both small towns and in cities, I think it may be a bit of the two things, tendency and cultural mythology. In American literature, particularly in rural fiction, as you’ve pointed out, the wounds do run deeper and vendettas tend to linger on, and I think that the blood feuds represented in rural literature do convey a sort of truth about how problems in general are handled in small towns as opposed to cities. Of course, with the globalization that’s occurred in the past couple of decades, and the unification, albeit superficial, that results from our cyberspace connections and the subsequent instant gratification, I’m not sure if these urban-rural distinctions exist in the same way they used to, or at least they aren’t as marked as they were before. Traditionally speaking, though, small town people have handled feuds differently than those in the city. That’s another reason why time is important in North Dixie Highway, because the novel takes place during the decades leading up to this shift, before the widespread use of the internet and the movement toward globalization. Up until that time, rural areas were much more ideologically isolated from urban centers than they are now, which, perhaps, made small towns more distinct in character. This fact was not lost on writers such as Twain, Faulkner, Caldwell, O’Connor, and others, and they did well emphasizing these differences to add another layer of sophistication to their respective fictional masterpieces. I believe that these writers recognized that there were real differences in how people handled problems in the city as opposed to rural areas, and they realized the importance of conveying these differences to demonstrate how the concept of community varies from place to place.

Simply put, the city has typically symbolized progress, and in much of the fiction set in the city, people handle traumatic situations differently than country folk. City dwellers may feel less able to act on the murder of a loved one because of the relative anonymity one experiences: there are so many people living in the city, where does one even begin to search for the murderer? Also, there are more random acts of violence in the city, so a person might become desensitized to some extent, and you might learn to mind your own business if the crime does not directly involve you or your family or friends. Having fewer people involved in these situations could accentuate this feeling of helplessness. This is certainly not the case in a small town. Everyone typically knows one another in rural areas, knows more than they should know about everyone’s business, and it’s much harder to keep a secret, to hide a murder, for example, without people finding out. For better or worse, the entire community would be affected by such an event, which might just as easily agitate the situation or help lead to resolution.

FWR: The chapters in your novel alternate between two consecutive decades in the narrator’s life. In the first he is a boy just shy of adulthood and in the second, a man just on the other side of it. It is easy to discuss the novel as a collection of linked stories, or as two intertwined novellas. When did these stories come together for you, and why do you think such modular forms appear to be gaining popularity?

JDH: North Dixie Highway actually began with a few independent stories, not as a novel per se, but I noticed a consistency of theme, voice and conflict and knew that it had to be a longer work—that the storyline deserved multiple angles and the kind of complexity that is more easily achieved in the form of a novel. You’re right that one might classify the book as intertwined novellas, or, perhaps, a unified collection of stories. Once I decided that all of this would end-up as a longer project, I tried to achieve an elusive, if not impossible, task: to write a novel constituted of chapters that work autonomously as stories. In some cases, I think I was able to achieve these story-chapters, and with other pieces, maybe the chapters are less effective as stand-alone pieces. In order to create unity in a longer work, a writer must, in most cases, sacrifice the autonomy of individual sections, whereas a truly effective story should be self-contained, so this can prove sort of contradictory. I admit that some of the chapters in the book are quite dependent on the book as a whole for their effectiveness, but they have to be in order to carry the work as a novel. The novel and the story, at least in a traditional sense, are truly distinct art forms in many respects, but such boundaries are often blurred in contemporary writing, and I suppose I was working to capture some of the elements that make both of these forms successful, combining the intensity of effect in the short story with the unity and development of a novella or novel.

The temporal shifts, I believe, are useful for showing what has changed and what’s stayed the same with the narrator and his physical setting as the story progresses. There are major gaps between events, of course, using this method, but I tried to follow the model of many great contemporary writers and tell the story through everything that is both there and not there, with multiple narrative lines boiling just under the surface.

I don’t know if I can speak for the popularity of modular forms, other than acknowledging that there has been a trend in this direction in contemporary literature. It probably all started with the fragmentary nature of the early 20th century modernist movement and the stream of conscious narrative. Then, at some point, it became a real trend in books, then film, especially in the 90’s and beyond. In the case of North Dixie Highway, it just seemed like the best approach to tell the type of story I wanted to tell: the narrative pattern reflects the state of mind, the consciousness of the protagonist. That may or may not be the goal of other writers who utilize this sort of modular form, but it was my primary motivation.

FWR: How important to you is faithful representation of a character’s consciousness, compared to more technical concerns like plot?

JDH: I see where you’re coming from, but from my point of view, with the way that I work, representation of consciousness is intertwined with plot—the two things can’t be exclusive of one another. I certainly care much more about representation of consciousness than some highly-structured, Victorian notion of plot, but I pay a great deal of attention to the structure of the work as a whole and how the story unfolds, even if the plot isn’t organized in a “logical” manner. The human mind isn’t logical, after all, so even though it’s impossible to mirror the function of the human mind through literary artifice, works such as Ulysses, for example, or even earlier examples of the novel, such as Don Quixote, or Moby Dick, come closer to achieving the desired effect. I guess that the point is that there is often more attention to plot in a novel than meets the eye when one considers that what seems to be a lack of structure, the elements which are not there, often serves as a catalyst to propel the narrative. I think the plot in my book manifests itself as a representation of a sort of selective memory process.

FWR: The characters in your novel do a lot of drinking. The male characters especially seem drawn to both its danger and its necessity, much the same as they are to the prospect of avenging their grandfather’s death. In the end, the two are brought explicitly together with the poisoning of his murderer’s scotch. Why, for these characters, do you think drinking and violence are so important, and so intertwined?

JDH: When I first spent significant time away from the U.P. as a young adult, one of the first things that I noticed was how people in other parts of the country seemed to drink so much less than many people in the U.P. do. I’ve often sat around with friends and speculated about why drinking culture is so akin to the lifestyle of many in northern Michigan. Maybe it’s the long winters, widespread unemployment, geographic isolation—I’m not sure why, exactly, but it’s a significant part of the culture there. Not everybody living in the U.P. is an alcoholic, but I think we have more than our share up there. The characters in NDH are representative of the region in a very real way, and that’s one simple explanation as to why drinking is so prominent in the novel. As a literary device, a character’s choice of alcohol is certainly a mode of developing that character; one can learn a great deal about a person by what they drink. Also, in NDH, as is the case in life, at times, alcohol is used to form bonds, or destroy them, as the case may be.

FWR: Do you have any objections to being known as a “U.P. writer”?

JDH: Not at all. When I was still living in the U.P., I was aware that writers such as Hemingway and Longfellow had written about the area. I knew that Jim Harrison, a native of northern Michigan, although not technically from the U.P., spent significant time there and that he had written extensively about it. He still does, along with fellow best-selling authors like Steve Hamilton and Sue Harrison, the latter a writer from a town that neighbors my hometown.

More recently, however, it has come to my attention that there is a thriving literary community centered on the U.P. that includes people who either live there, use it as a backdrop for their literature, or both. At the center of the movement to bring more attention to Upper Peninsula literature is the playwright, poet, editor, and author of the novel, U.P., Ron Riekki. He recently put together an anthology of new Upper Peninsula works with Wayne State University Press, The Way North, and it just earned a Michigan Notable Book Award. Through his efforts, I’ve come in contact or reconnected with U.P. writers such as Mary McMyne, Eric Gadzinski, Julie Brooks Barbour, and many other talented people. Many of the authors included in the anthology were names that I’d recognized from other important national venues, people like Catie Rosemurgy and Saara Myrene Raappana. Needless to say, there is a burgeoning literary movement centered on U.P. writers, and there are certainly countless other talented writers that I’m forgetting to mention here. The literature of the U.P. includes a broad range of styles and themes, but I’m glad to see that the writers of the region are getting some much-deserved national recognition.

|

“Lyrical, passionate, unflinching, Joe Haske’s fiction grabs hold of you and shakes you to your core. He is one of the most exciting young American writers of his generation.” ~Richard Burgin |

Read “Red Meat and Booze” in Issue 4

|

More Interviews |

- Published in home, Interview, Series, Take Four, Uncategorized

Take Four: An Interview with Megan Staffel

In this installment of “Take Four,” we talk to contributor Megan Staffel about her short story “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” and her latest collection from Four Way Books.

FWR: “Like “Saturdays at the Philharmonic,” many of the stories in your book Lessons in Another Language portray characters in the midst of some form of sexual awakening. Though the stories are set in the late sixties and early seventies, the characters’ experiences with sex seem more painfully emotional than the narratives of freedom and personal autonomy we so often associate with that period. What are your thoughts on the relationship between subject and chronological setting?”

MS: Culture changes so slowly we don’t see the changes until we hold a memory against the present. In my last collection, Lessons in Another Language, I was compelled to revisit the period I grew up in through fiction because I understand it differently now that I am an adult. I feel a bit wiser because of experience, but I’ve also gained a different perspective through the cultural changes I’ve lived through. That’s where sex comes in. As a culture, it seems to me we are less naïve. I believe (I hope) we are more nurturing of young women. These are generalizations of course, and they’re suspect because they are generalizations, but that’s why we need fiction. Fiction gives us the specifics.

There was a house in my childhood that contained all of the things I didn’t understand. I’ve revisited that house in dreams and in stories. It’s a house my mother spent her summers in as a child and I visited as a child, a big and forbidding stone house built by my grandfather at the foot of a wooded hill in Connecticut. It had a distinctive sound, a wooden screen door snapping closed, and the distinctive smell of old fires in a stone fireplace, and these sensory memories are what launched me into the group of stories that make up Lessons in Another Language, most of which are about characters in the in-between territory after childhood, but before becoming independent adults.

There was a secret in every drawer of every cupboard in that house and in the early sixties, as I wandered about by myself, pretending I was Nancy Drew searching for clues, I found only the mangle sitting by itself in the center of a small room in the attic and in my grandfather’s dresser drawer, a collection of pornographic photos. At nine years old they were both frightening and compelling, but thinking about them now, they gain meaning. My perspective now, influenced as it is by the culture of the 21st century, prompts me to ask, why was it necessary to sleep in ironed sheets, and what an extravagant waste of time it was for the woman of the house to create them, and behind that question is a more interesting one: did my grandfather ever tell his wife his fantasies? I think not. I think they were both constrained by their ideas of married life. He spent his days on the golf course while she was in the attic, running wrinkled sheets through the hot rollers on the mangle, making them crisp and smooth.

When a story takes place is as important as where it takes place, and I would say that the word “setting” includes both place and time and gives them equal importance. The story you mention, “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” was written after the publication of Lessons, but it was written from the same retrospective point of view that inspired the stories in that collection. And yes, you’re right, the sixties and early seventies urged us to enjoy sexual freedom, but that was a reaction against the constrictions of the fifties and also, probably, a direct result of the development of a birth control pill for women. Yet as freeing as the pill was, it also wreaked emotional havoc because we were girls formed by the sheltering mores of the fifties. That’s what’s so fascinating about history. The extremes of one decade “correct” the extremes of the previous decade. For instance, that ubiquitous Beautiful Hair Breck blonde whose pale features were on the back cover of every Life and Look magazine I saw, was the utterly convincing messenger for Breck shampoo and the icon I and many other young girls worshipped. Her every hair was in place and her face was so calm it was death-like. That purity was the ideal of beauty we sought. That is, until the sixties bottomed out and Jimi Hendrix screamed, “Are you experienced?” Then, she was no help to us at all.

Where a story sits in time gives the writer a perspective to work from. It provides the particular images, sounds, and smells that bombard our characters, but perhaps most importantly, it gives us the context that pressures the choices a character makes in his or her life. When is often the subject of the story, but at the very least, it’s a supporting element, one that’s impossible to peel away from character or events.

FWR: I’m intrigued by the idea that, in a world in which generalizations are a necessary evil, fiction has the potential to provide us with specifics. It seems art is so often accused of being too generalized, too abstract to serve much of a purpose.

MS: I suspect those accusations are from people who aren’t readers, who haven’t had the experience of “living” in a story or a novel and then missing it when it’s finished. When you have truly inhabited a piece of fiction, long or short, it feels like a complete world and the odd and marvelous experience of reading fiction is that it’s both real and imaginary, actual and invented. That is, we are experiencing what are only black marks on a white background while at the same time, we are translating their message. The black marks don’t, of themselves, create the illusion of reality; they need to be partnered with a mind to create that illusion. They are the code we translate to get access. With movies and TV, there’s no code. But we must partner with text and that’s why it has the potential to envelop us. And when it envelops us in a complete way, that is, when the illusion it creates captures us so utterly we don’t question anything (i.e. we suspend disbelief) it can rescue us from the banalities of our culture.

Those of us who are readers depend on this form of rescue. The specifics in the world of a novel or story are the antidote for the mind-numbing generalities in the commercial muck we slosh through in our daily lives. We tune a lot of it out of course; we have to. I tune out most of it because I live in a rural place and don’t have a TV or subscribe to the contemporary versions of the Life and Look magazines of my childhood.

But still, I am part of it. Leafing through the New York Times “Sunday Styles” magazine I see the word Aruba, and then below it: “Unwind on one of the best beaches in the world.” The photo shows an empty beach with a hand-holding couple walking away from a rocky cove in loose, wind-rippled clothing towards the foamy surf. I am spying on them from a hidden vantage point somewhere above.

What’s being suggested? Sex, of course. The photo shows us a post-coital moment. And then there’s the word unwind, a gloriously general term with nothing but positive implications supported by the curving shoreline, the curving path of the footprints, the body-hugging style of the sheath dress the woman wears, the flapping, unbuttoned shirt on the man. It’s rich in implication but starved of substance.

Fiction writers manipulate just as boldly. Our manipulations, of course, have a different purpose: we don’t try to numb our readers, we want to wake them up, to remind them of the finite quality of our individual material existence.

I like the word “material.” I am an epicure of the material world, in love with the concrete, sensory plain that supports our existence on this earth and perhaps my underlying purpose, as a writer, is to steer my readers away from that Breck woman, that Aruba fantasy, those abstract and generalized visions, back to the disquiet of the sensory.

As I am writing this, I am sitting on the porch of this house I share with my husband. It is late August and I look out at beds of flowers. This summer I have planted a lot of long-stemmed zinnias. They are a great flower for cutting and a wonderfully generous creature because the more you cut its stalks, the more flowers it will produce! And so our house is filled with vases of flowers and each time I walk by them I admire the shapes, colors, textures. But they last only four or five days. The daisy-like heads on the zinnias fall over, and all their intense, startling beauty turns to dross.

In the sensory world nothing lasts. A flower in full bloom; a moment of true communication in a relationship; the infectious laughter at a dinner party; a phrase in a tune that is perfectly melded into a movement with a partner on a dance floor: these stunning moments all pass. And yet these are the concrete experiences that energize us. So we go to art because the painting, the photograph, the conversation in a novel are the only ways of keeping them with us.

And, in a wonderful way, the art that catches that perfect instant in time isn’t static either. That is, it doesn’t stay on the canvas or on the page; it visits and informs the actual. So, a particularly beautiful arrangement of flowers that sits in a window in my kitchen reminds me of Matisse’s 1905 painting , “Open Window,” where color literally leaves the petals of the flowers and rises into the air.

In Shirley Hazzard’s 1980 novel, The Transit of Venus, there is an amazing scene between the duplicitous Paul Ivory and his one-time lover, Caro Bell, when Paul Ivory confesses not only his affairs with men, but a dark moment from his early life that resulted in a death that was deemed accidental but in fact was not. “I killed him,” he tells her. “I thought you probably knew.”

Paul believes Caro knew because his rival for Caro’s love, Ted Tice, had witnessed the “accident” and guessed the role Paul played in it, and Paul assumed he had told Caro. But in fact, he hadn’t. This is a startling revelation for both the reader and Paul Ivory because it means that Ted Tice is a scrupulously moral man. Even though Paul Ivory had been his competitor, Tice did not malign him. He wanted Caro to choose which man to love on her own and not because she had learned that Ivory had a dark past. So when Ivory confesses all, Caro sees Tice differently, and for the first time in the many years he has pursued her, she is ready to respond to his romantic overtures.

It takes an entire novel to set up this reversal and though it’s a development specific to this group of people, it spills out beyond it. That is, because it’s so specific, its truth is universal. It illuminates the complicated layers of human relationships in general. What it suggests to me is that the tangles in my own life, though different, are not so strange. So this is another way fiction can rescue us.

And then there is the curious comfort of the invented world. I think it unites us with our more playful, childhood selves. I am a great believer in the adult necessity to “play pretend,” and fiction ushers us through that portal; it allows us to exit the real and experience the rejuvenating qualities of imaginative possibility.

I believe art helps us to accept life’s messes. It provides release through catharsis. But it can do so only if it relates to our sensory existence, that is, if it communicates with the same specific and material world we inhabit.

FWR: So, in a way, art not only gives us rich experience, but the possibility of revisiting and reinterpreting that experience many times. You say the stories in Lessons in Another Language were partly an attempt to revisit the cultural moment of your youth. The book, of course, presents specifics – material, I suppose – perhaps not all of which was originally present in your memory. What do you think it is about the act of writing itself that lets us access or interpret our experiences better than memory alone?

MS: In my brain, and I will assume that this is true for others as well, the stories I tell myself about events that have happened in my life have a minimalized quality, an owner’s shorthand, that makes them knowable in an instant and habitual way. When these stories are translated into a narrative that will make sense to someone who is not the owner, there is a great deal of invention. Memory is patchy and so the supporting material must be filled in.

Should it be filled in with the purpose of telling the truth or with the purpose of telling a particular story? As a writer, I never take the first option. I’m not a memoirist; I’m not interested in what we call objective “truth,” what actually happened; I’m interested in what almost happened or what might have happened. I am bored if I have to stick to what I already know. I want to throw the doors open and invent! Invention allows more light, more air and thus, a new perspective. Invention creates the possibility of discovery. Also, it eradicates the memory groove and that’s a good thing.

The story in Lessons In Another Language that is the closest to actuality is called “Daily Life of the Pioneers” and two marvelous things have happened since that story has been published. One is that I have lost much of the original memory because the invented narrative has taken its place. And the other is that the first time I read that story, my audience laughed. I was, of course, hoping that they would laugh, but they did truly laugh and they laughed not just once but frequently. So the “real event,” the summer that my sister and I were sent to an Alexander Technique and raw-foods sleep-away camp in the wilds of Pennsylvania, was changed forever. Now it’s funny and awful, so I’ve been able to abandon the original dark and serious version, the memory I used to have to drag around.

But the true value of invention is that it allows the writer to approximate the cacophony of feeling we human beings possess. It seems to me we are always at the mercy of inchoate feelings — they are massively conflicting and difficult to articulate. And then to make everything more challenging, the actual events of our lives often lack the spectacle that our feelings suggest. So how do you get at them? I invent. Invention is the tool that gets us closest to the expression of those feelings.

Here’s what I mean: When I was a little girl I joined a Brownie troop. It was probably about 1959 and my mother, an abstract expressionist painter who worshipped color and led a bohemian artist lifestyle, was minimally supportive of the whole project. When she could no longer procrastinate the purchase of the outfit, she took me to the department store and I picked out the brown dress, the brown belt and the brown socks. To be a Brownie, that was what you had to wear. We gathered these items and then, on our way to the cashier, we passed a table of Brownie extras, things to improve the Brownie lifestyle. One of those was a little brown plastic change purse designed to hang on the belt. Brownies had to pay dues at each meeting and the purse would give me a place to keep my money. It cost only ten cents and I wanted it, badly, but my mother was determined not to spend another penny on such abhorrent items. Quickly, she slipped it into her handbag. It was a small thievery and yet, relative to my decision to join the troop and aspire to be a good Brownie, it was enormous. I felt ashamed, scared, guilty, and desperately unhappy. My mother paid for the other items and we walked out of the store.

Were I to fictionalize this, I would have to add things to increase tension. Maybe there would be a store cop. Or maybe a cashier would look our way. Maybe the little girl character would notice mirrors hanging down from the ceiling to apprehend shoplifters.

Because that’s what it felt like my mother was. The filching of the change purse was huge and it was irrevocable. It put us on a path I didn’t even know existed. Yet for my mother it was a simple and very small incident; she was only out of patience, with me, with the culture, and with her life as it was at that moment in time.

Lately I’ve been working on a novella about a young woman’s first romance. As many of us do, she chooses an inappropriate boyfriend, a sex addict and compulsive liar, and gets so entrapped by his version of reality she forgets that it isn’t her own. It wasn’t until I had finished the story that I realized I’d made use of my first boyfriend. I’d changed his context and given him better accomplishments — the invented boyfriend was a professional dancer —whereas the only creativity the original possessed was a remarkable timing and visual acuity that allowed him to do a reckless highway ballet that should have caused accidents, but only caused a woman to drive up alongside us and tell him she was glad she wasn’t my mother because if he kept on doing what he was doing, I was going to be dead. Oddly enough, her words had no effect. He was high and I was so numbed by constant fear I shrugged it off.

When I recognized that relationship in the novella I was surprised. I hadn’t set out to use that material, but I think memory is always guiding us. From the perspective of my invented characters, that crazy summer of my life suddenly looked very different. For the first time, I could see the absurdity.

I hadn’t set out to use that material, but memory must have been guiding me. And now with the novella complete (I won’t say finished because nothing is finished until it’s published) I am pleased that I’ve fictionalized a secret time in my life. When it goes out into the world, and if it creates a spark of recognition for some readers, that’s the real pleasure.

|

Not since Alice Munro’s The Beggar Maid has there been a book which so articulately reveals the complex |

Megan Staffel reads “Saturdays at the Philharmonic”

|

More Interviews |

Take Four: An Interview with C. Dale Young

In the second installment of our new interview series, “Take Four,” we talk to contributor C. Dale Young about his new work in short fiction, the subtle differences between poetry and prose, and the alchemy of characterization.

FWR: As an artistic mode, poetry seems to have served you well in the past. Was there anything in particular that turned your thoughts toward fiction?

CDY: First of all, thank you for saying poetry has served me well. Most of the time, I question whether or not I have served poetry well… I began writing with the belief I would be a fiction writer, a novelist. But I discovered poetry in college and found I had a better facility, a quicker facility, with it. I became discouraged about writing fiction. Later, as I began to publish more and more poems, fiction became something I remained interested in but then became afraid of writing for fear I’d look like an idiot. But I went to give a reading at Oregon State University six or seven years ago, and I did a roundtable discussion. It came up in the discussion, by the fiction writers there, that it seemed odd I didn’t write fiction. I think I laughed it off. But at that time, I had been trying to do something different with my poems, something requiring more than one voice, more than one mentality, and I was having real difficulties executing that. Maybe a better poet would have been able to do that, but I couldn’t.

On the way back to the airport, on a shuttle between Corvalis and Portland, this sentence came into my head: “No one would have believed him if he had tried to explain that he watched the man disappear.” I typically come up with the last lines of my poems first, but try as I did, this sentence did not seem like a line of one of my poems. I joked with myself, there on the shuttle bus, that maybe this was the start of a short story. So I poked around at the sentence in my head and then wrote it down on a piece of paper. As I looked at the sentence, I changed it to: “No one would have believed Ricardo Blanco if he had tried to explain that Javier Castillo could disappear.” I knew this was not a line from one of my poems, pulled out my laptop and typed the sentence. By the time I reached the airport, I had written about 700 words of this story that would become “The Affliction.”

I have no idea why at that moment I would start writing a story. And maybe I was able to start a story for years and years but never paid attention. I am not sure. But that story I wrote ended up prompting several other stories, some about the characters in “The Affliction,” some narrated by them, some about ancillary characters. That story opened a world for me that I haven’t really left yet.

FWR: As you mention, the character of Javier Castillo in your story “The Affliction” is literally able to disappear. In the end, he does so permanently. This is an interesting contrast to Leenck in “Between Men,” a character who also faces the prospect of literal disappearance, though in this case it’s decidedly against his will. What do you find attractive about the subject of disappearance, voluntary or not?

CDY: I have to be honest; I wasn’t aware of my attraction to disappearances. But now that you bring it up, it seems to exist in my poems as well. Several of the poems I have written in the last 7 years have this idea of disappearing in them. I guess that isn’t so odd seeing these stories were written in the same time period. But wow, I wasn’t aware of that until you just brought it up.

In my day to day life as a physician, as an oncologist, I am keenly aware of people disappearing. Some fight until the end of their lives to stay present, and others give up and disappear long before their physical bodies do. The ways in which the mind deals with mortality have always interested me, and it occurs to me now that my attraction to this idea of disappearance might stem from my own mind working this out. I am not entirely sure, though you have given me much to think about!

FWR: When writers talk about the differences between poetry and fiction, there’s often some “grass is greener” mentality on both sides of the fence. As well as a lot of wondering whether or not “crossing over” is even possible. Having had some experience with both, do you think there’s really as much difference between the forms as we seem to think there is?

CDY: Well, we all, poets and fiction writers, come from the same heritage, the epic poem. Some forget that in the scope of literary history, the novel is a fairly new thing. Both poets and fiction writers, in order to do what we do well, must not only tell a story but create an experience, or the sense that one as a reader is enmeshed in the experience. Lyric poetry tries to provide a flash of an experience, something brief and intense. Most fiction provides a more gradual enveloping of the reader into the world of the story or the novel. Many of our tools are the same. But the genres are different. Their ways of captivating readers are different. At base, the tools might be similar or the same, but the execution of the writing and the goals of the writing are usually different. I guess what I am saying is that poets have much to learn from fiction writers. Studying fiction allows them to better see the speaker of a poem as a created thing akin to a character in a novel. And fiction writers have much to learn from poets. Studying poetry allows them to better use figuration, to set scene with a keen eye, etc. Some “cross over” to use your phrase. Many will never feel a desire to do both.

FWR: In an interview for the American Literary Review you said that you once “…falsely believed that the love poem was in essence a dead form… What I realized with time is that the love poem isn’t dead but just incredibly difficult to pull off…” Both “The Affliction” and “Between Men” evoke beautifully complicated forms of love. Do you think love stories are just as difficult? What do you think makes these particular stories work?

CDY: I suspect the love story is also a “dead form.” Like the love poem, one must be ever vigilant when writing a love story to avoid the trap of cliché. This is incredibly difficult. I don’t think of “The Affliction” as a love story. I suspect I actually think of it more as a falling out of love story, which is just as dangerous. I didn’t conceive of “Between Men” as a love story, and I resist the idea of it being a love story. But I do see why you would raise the issue. In many ways, Leenck wants to love Carlos but cannot. And yet, in the end, it is his love for Carlos, in whatever form, that does him in. As for what makes these stories work? A little bit of hard work and a lot of alchemy. A lot of alchemy.

FWR: Alchemy. That’s an interesting word. I think you’d agree that stories often start to cohere at the moment their characters – and their characters’ relationships to one another – become complex or detailed enough to give the story life. Have you ever been surprised by one of these moments?

CDY: I have. These moments have happened to me countless times over the years, both in writing poems and stories. In the two stories you mentioned, one spawned the other. The narrator of “The Affliction” is the Carlos in “Between Men.” My desire to “know more” about Carlos led me to this story. And the sons and wife of Javier Castillo end up having their own stories. And even the most recent story I drafted examines one of Javier’s sons who is locked up in a ward for mentally unstable people who have committed crimes. This discovery of the person within and behind the story is what keeps me going back to the writing. I need to know, and that need is what many times generates the story. The story might start with an image or a sentence or a realization in my head, but the stories always move forward as I figure out the characters, what motivates them. It is funny, but Carlos, Javier, Leenck, Flora Diaz, these characters I know I created, seem to me, at times, very real people, something that must have come not from inside but from without. And that is alchemy to me; something not magical, perhaps, but close to it.

|

“With clarity and precision, the poems uncover the secrets of blood and lust and heart, the nature of selfhood, and the accompanying larger social and political implications of identity. Beneath all this is a quest for beauty and evidence of the poet’s deeply humane intelligence and the breadth of his sensibilities.” —Natasha Trethewey

“Between Men,” by C. Dale Young

|

|

More Interviews |

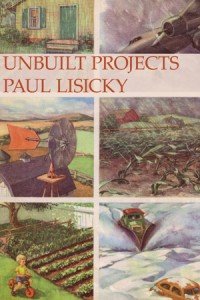

Take Four: An Interview with Paul Lisicky

In the first installment of our new interview series, “Take Four,” we talk to contributor Paul Lisicky about his short story “Lent” and his latest collection from Four Way Books. In between issues, we’ll keep the conversation going as more contributors share their thoughts on recent work, current projects and the challenges of writing well.

FWR: As one might expect in a story called “Lent,” there are a number of references to abstention, and to the intentions that motivate its practice. In this way the story reveals an interesting tension between spirituality and modern life. Do you think that anyone still knows how to abstain, or is abstinence no longer considered a virtue?

PL: That’s a great question. Father Jed, the central character in that story, certainly tosses around some ideas about abstention, but I think his thoughts probably have less to do with virtue than they do with some kind of personal crisis. He’s so concerned with correct appearances (i.e., Father Ben’s mismatched shoes) that he completely misses the fact that the guy is levitating. I actually think the story is pretty much on the side of permissiveness when it comes to spiritual matters, even though Father Jed is the lens of it. I sort of expect the reader to identify with the people in the assembly, who might be doing just fine with their liturgical dancers and folk hymns.

It would be interesting to write a story that seriously considered the abstention question. Most of my books have been about desire, the paradox at the center of it – how it sustains us as it ruins us – but not so much about pure refusal. It seems to me that many people around us are in the practice of abstaining from one thing or another all the time – think about AA or NA or SAA and how entrenched those programs are in urban life – but maybe that’s another matter. Abstention is different if you don’t already have a problem with excess. But how can anyone not be in some difficult relationship with excess in a culture that encourages so much wanting?

FWR: It’s interesting that you say most of your books are about desire. It’s obviously an important aspect of fiction. Kurt Vonnegut famously said, “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” But in good fiction it’s usually more complicated than that. Perhaps what’s missing from a story in which someone simply wants a glass of water is this tension you’ve mentioned, between desire’s power to sustain and its power to ruin. Would you agree? And would you say that much of your own work begins, conceptually, with this tension in mind? Or does it more often evolve naturally from character?

PL: I’d definitely agree – desire is always a two-headed beast, and I’m not even interested in pursuing a story until I can find my way into its opposing energies. Usually a story doesn’t start with character for me, but from situation or image. Right now, I’m writing a little story about a toll taker on a highway, a woman who leaves her corporate job behind to pursue a childhood dream. The tone of it is tongue-in-cheek and not. I just know I wouldn’t be able to write the story unless I were focusing on the image of the tight space my character has to occupy as the cars are aiming at the toll booth at high speed. So a story for me starts with the metaphor, and the metaphor has to be in sync with sound – by that I usually mean an opening sentence with a particular cadence. Once I have those two things in line, a character can emerge. I can’t imagine working from character alone – human beings can be so inscrutable, all over the place – but then again I’ve never exactly been a realist.

FWR: Religion seems to be another common theme in your work, though it often functions as a lens rather than the object itself. For example, “This is the Day,” a story from your new collection, Unbuilt Projects, presents Christian mythology as a kind of philosophical system, which the narrator uses to interpret an emotionally painful reality.

PL: It’s funny you should be asking this now, as I’ve been going through the last draft of a new memoir, and I was just telling myself to “get rid of this holy stuff!” By holy stuff, I’m not so much talking about thinking, but a borrowed pitch or tone that presumes the reader’s going to hear it and align with it. I can’t stand coming upon that, and my bullshit detector has been razor sharp about it these days.

I’m a big fan of people like Noelle Kocot, Joy Williams and Marie Howe, who are all pretty open about the subject of God – or they’re at least asking questions about God in their work. Marie is a good friend, and I was actually reading The Kingdom of Ordinary Time in manuscript as I was writing the first pieces of Unbuilt Projects. Marie’s book pretty boldly riffs on scriptural narratives, and I took direction from it. She’s not writing didatic work; she’s, as you say, using the mythology as a philosophical system.

I think there’s a lot of anger and bewilderment about God – or around the subject of God – in Unbuilt Projects. That wasn’t made up. The structures that I’d grown up with, the system that had sustained me, even though I wasn’t always aware of it as an adult – were shattered for a time by my mom’s confrontation with dementia. You can hear lots of anger in “How’s Florida?” and “In the Unlikely Event” and “Irreverence.” But I’m glad the book also has pieces like “The Didache,” so that the implied question – ”What kind of God would allow this to happen to someone who matters to me?” – has another side. I wouldn’t want that question to simply generate rage. Rage isn’t the whole story, it never is.

FWR: It sounds like the stories in the book were at least partly cathartic. Of course most literary fiction is written for the author’s benefit as well as for the reader’s, but in some cases this seems more so than in others. This more personal work must come with its own unique difficulties. Do you have any advice for writers who find themselves staring down similar projects?

PL: My favorite stories and novels always have a sense of necessity about them. They feel impelled. It’s hard to say exactly what “impelled” is, but we feel it when we’re reading it. Maybe we could say that the work has come into being out of the writer’s suffering. Maybe it digs into the why? of the situation – which is unanswerable, finally. It doesn’t feel like the writer has even chosen to write such material. It’s chosen him or her – maybe.

I think if you can choose whether or not to write a difficult personal experience, then maybe you shouldn’t write it. Or not write it directly, at least. Find another narrative (or set of metaphors) in which to plant that energy. Mere transcription is never enough anyway. It always has to be about craft, distinctiveness of expression. Exactness of pitch and pacing. The sentences.

Catharsis is a funny thing. I’ve been reading Joy Williams’ 99 Stories of God and I keep thinking about this passage:

“Franz Kafka once called his writing a form of prayer.

He also reprimanded the long-suffering Felice Bauer in a letter: ‘I did not say that writing ought to make everything clearer, but instead makes everything worse; what I said was that writing makes everything clearer and worse.’”

The slyness of that passage might not be available out of context, but I completely get what it’s suggesting. I didn’t feel lighter or wiser or stronger after finishing Unbuilt Projects or The Narrow Door, the new memoir. I might have in fact felt “worse” afterward – who knows? I kicked a lot of questions around, questions that felt necessary to give form to. That’s the most of what we can expect of the things we make, at least on the personal level. We’re lucky to have tools that can possess us completely (in our case, language) when the people and places we love might be falling down around us. Frankly, I don’t know how anyone thrives, much less endures, without having sentences or musical phrases or paint or whatnot at their disposal. That’s the biggest mystery to me. I want to know how those people do it.

|

|

|

More Interviews |

“This is meant to be the story of all lives, though I’m talking about one in particular,” Lisicky writes, and if the goal of Unbuilt Projects is “to be the story of all lives,” Lisicky has succeeded. Adept at harnessing the highs of life that are ruthlessly countered by lows— “see how the plants grow. And die a little”—these pieces are anchored by truths and by Truth. With an aptitude for creating vivid scenes, Lisicky envelops us in his stories, so though we did not stand under “The sky so scrubbed with stars it hurts,” it is as if we did.

“This is meant to be the story of all lives, though I’m talking about one in particular,” Lisicky writes, and if the goal of Unbuilt Projects is “to be the story of all lives,” Lisicky has succeeded. Adept at harnessing the highs of life that are ruthlessly countered by lows— “see how the plants grow. And die a little”—these pieces are anchored by truths and by Truth. With an aptitude for creating vivid scenes, Lisicky envelops us in his stories, so though we did not stand under “The sky so scrubbed with stars it hurts,” it is as if we did.