JUNE INTERVIEW WITH STEVEN ESPADA DAWSON

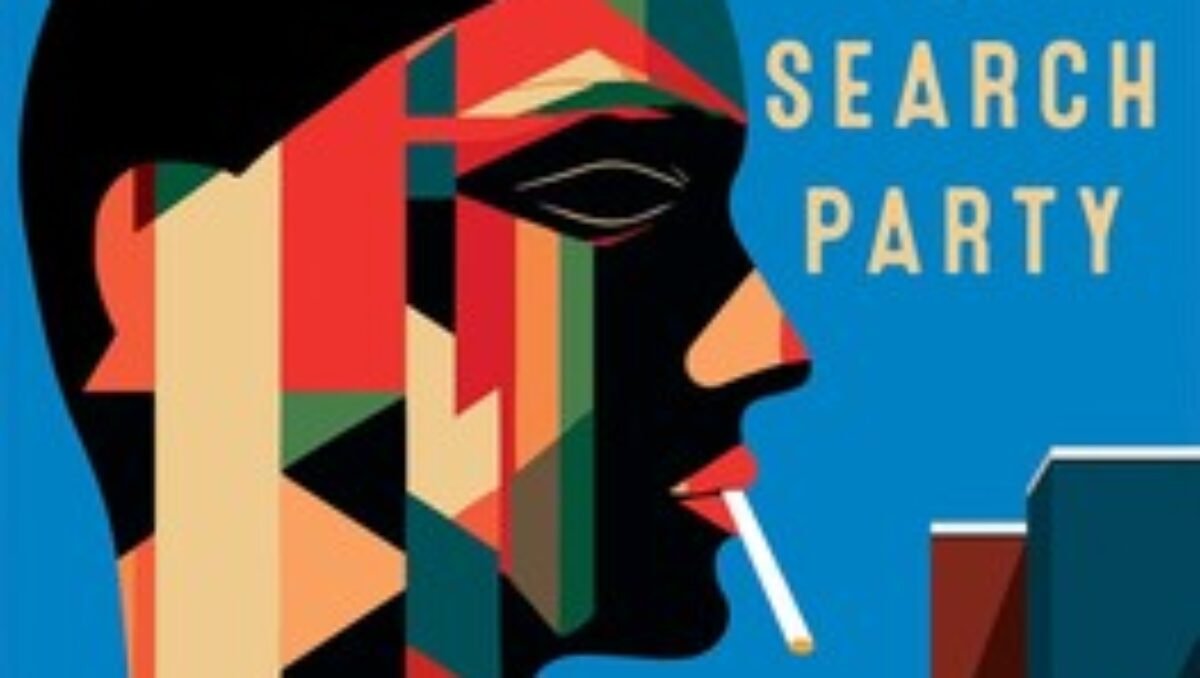

Late to the Search Party is the debut collection of Steven Espada Dawson, exploring the individual and precise depths papered over by common nouns like ‘grief’ and ‘family’. The elegiac collection delves into Dawson’s love and grief for his dying mother, the decades-long absence of his addict brother, and the absence of a father, with language that is clear and resonant as he explores the “gorgeous myth of childhood” and “how to make a family/ from just one man”.

FWR: One of the epigraphs (“A hole is nothing/ but what remains around it”) is a line from Matt Rasmussen’s collection Black Aperture, which focuses on the death of his brother. Late to the Search Party also names and circles around loss, specifically the death of your mother and the disappearance of your brother. In constructing their portraits, the reader also sees you and your loss, your grief, come into focus. This isn’t so much a question as acknowledging its effectiveness! But to turn it into a question: can you speak broadly about the development of the collection? Was the hope in structuring the collection in four parts to have these portraits in conversation?

SED: The two epigraphs that open the book—from Rasmussen’s Black Aperture and Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec—acknowledge the windows I climbed through to make my own book possible. I owe those poems and people so much. They helped shape the emotional landscape of my writing about my family. (Another special shoutout to Diana Khoi Nyugen’s huge and brilliant Ghost Of that was also a pillar of possibility for me.)

As you mention, Rasmussen’s book orbits his brother’s death by suicide. There are not many books about missing addict brothers (or at least I have not found them), but unfortunately there are many books written post suicide. I found myself gravitating a lot to those works because they carry with them a familiar grief and energy. You have these sudden disappearances with often a lot more questions than answers. Diaz’s first book always felt like a family reunion. It’s really a singular, strange feeling to love an addict. It’s easy to hate them and retreat into that certainty. It’s harder to complicate them and hold yourself in their world of uncertainty. Diaz has always showed me how to lean into that. I’m thinking about that quote from James Baldwin: “You think your pain is unique in the history of the world, and then you read.”

During my MFA I was taught to resist writing in fours because its formal stability tends to slow things down, and you’re often looking for modes of propulsion—especially in a longer format, like a book. I arranged the collection into four parts to mirror the elegy series and the title poem, but it’s also to slow things down—something that felt necessary when writing around two family members at the fringe of life and death. I wanted to hold time more carefully.

FWR: I was struck by your return to elegy throughout the collection, specifically the recurrent title of “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Brother’s Heart,” which at times is “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother’s Heart” and “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Heart.” Can you talk a bit about the genesis of those poems? Were they always meant to be in refraction with each other?

SED: I started writing those poems after the shape of a book felt possible, and I needed a throughline to thread the disparate sections, starting with “Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother’s Heart,” then my brother’s heart and finally my heart. I resisted writing an elegy series for my father to mirror his absence in my/my speaker’s life, which to me serves to echo his silence.

The heart elegies were originally published as single poems in four sections, similar to the title poem “Late to the Search Party.” I broke them apart after a recommendation from Eloisa Amezcua, one of my first readers. I was always struck by the way José Olivarez separated “A Mexican Dreams of Heaven” in his debut collection Citizen Illegal.

After separating the sections into their individual poems—with a lot of adjustments so that they stood on their own—I immediately felt like the whole thing was a lot more sustaining. For me, a series has a way of acting as a pulse check in a book. I wanted to tell the speaker and the reader “Hey, remember this? Don’t look away from it.” I wanted to capture the discomfort I felt while writing those poems.

FWR: Several of the poems return to your childhood, with a real tenderness, even as “nostalgia rends/ in absence”, as you write in “At the Arcade I Paint Your Footsteps”. How did you balance the (assumed conflicting) emotions as you delved into the past (with the knowledge of hindsight) and the uncertainty of the present?

To expand, I’m thinking of the poem “Lucky”, in which it’s revealed that the speaker’s brother has taken him to the dope house during a time when he’s meant to be babysitting. Despite the awareness of the speaker and narrator to the reality of the situation and the “guardian angel taking work naps/ among hallway sleeping bags”, the emotion I’m left with isn’t anger, but an understanding of the flaws in “someone’s idea of a hero.”

SED: When I first started writing poetry about my family, my experience of nostalgia was often split in two. It’s easier to come to terms with things when you can separate the good from the bad and take them in separately, one at a time like a DMV line. I think that can unintentionally flatten the reality, which is that (for so many of us) happiness threads itself through grief constantly, and vice versa. I think a project of this book is to bring those parts together and make a clearer picture of a more whole, honest reckoning.

I remember when I was young, and my brother asked my mom for $20 to take me to the arcade, then $20 for gas there and back. There was no car. We walked miles to the mall, looked at all the games but didn’t play them, then walked back. I understand that he took advantage of my mom and I. We did not have that money to spare, and he likely threw that cash into his addiction. I also understand that we spent real time together then, and he’d tell me stories about his life and the neighborhood, offer me the brotherly wisdom he thought might help me survive better than he did. Nostalgia can work that way. Insidiousness and sweetness share a bedroom wall.

FWR: There’s lots of touchpoints to nature in these poems, beginning with the first poem, “A River is a Body Running”. A poem like “Orchard”, which has all of this lush imagery used to articulate the growth and ravages of cancer really jumped out at me and reminded me of classical still life paintings, which always include an element of rot (a fly on the fruit, for example). Would you talk about how you brought in those elements of the pastoral?

SED: I grew up in a big city and was never afraid of loud traffic and big attitudes but was always nervous about the idea of a quiet forest, a sudden cliff, vast open water. I currently live on land pinched between two lakes, and it still terrifies me a little bit (see poem: “Lake Mendota, After Sunset”), but I’m getting better through exposure. (Though you will never catch me out on the frozen January lakes like so many of my neighbors.)

When you’re writing a book in places where nature is unavoidable, the flora and fauna and weather start to creep into your work. You’re taught to be a radical noticer, so everything starts to get vacuumed up into the same bucket. Suddenly the human entanglements filling in all the blank spaces become clearer. Heroin lives on the same page as opium poppies because they are fundamentally linked.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Interview, Poetry, Uncategorized