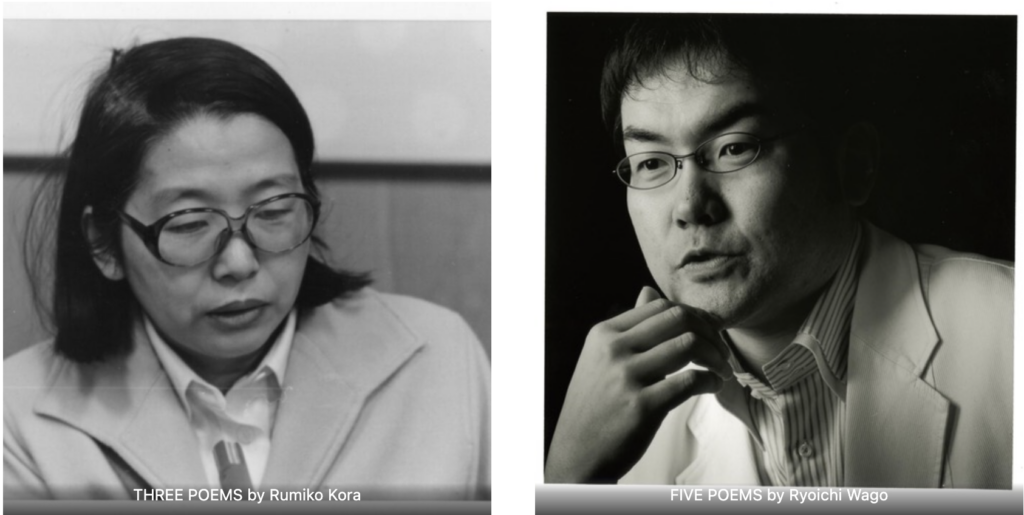

INTRODUCTION TO KORA RUMIKO & WAGO RYOICHI by Judy Halebsky

THREE POEMS

by Rumiko Kora, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

FIVE POEMS

by Ryoichi Wago, trans. Judy Halebsky & Ayako Takahashi

This folio shares recent translations from two Japanese poets, Kora Rumiko (1932-2021) and Wago Ryoichi (1968-). Kora’s poems are from the second half and 20th century, and Wago’s were written following the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown that devastated his home region. Writing in different times and from different perspectives, these poets overlap in that their writing draws attention to environmental degradation and inequality while simultaneously voicing a strong sense of place.

Kora was born and raised in Tokyo. Her childhood was shaped by the Second World War and the devastation of the Tokyo fire bombings that she witnessed as a thirteen-year-old. In the changes of the post-war era and the rapid industrialization of the 1970s, her neighborhood grew from a small community to a bustling urban area. Her writing speaks against capitalism and colonialism. At a time when many Japanese writers were influenced by European literary forms, Kora looked toward writers from Asia and Africa, all while drawing inspiration from mythology, envisioning matriarchy, and speaking to the harms and costs of nuclear weapons and nuclear power.

These themes are evident in her poem, A Mother Speaks, which is set within the Noh play A Killing Stone (Sesshôseki). Noh is a somber, serious theatre tradition that has been in living practice for more than six hundred years. Plays often have themes of connecting the dead with the living and of vanquishing evil spirits. A Killing Stone references the legend of the fox spirit and Lady Tamamo’s attempt to use her supernatural power to kill the emperor. As the story goes, her plans fails and her spirit is relegated to a stone that kills any living thing that passes over it. Kora’s poem envisions Tamamo’s power, fertility, and the potential of transformation, offering an embodied, feminist perspective on the Noh play and the legend more broadly.

Wago is a high school teacher and has lived in Fukushima prefecture his whole life. In March 2011, when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear powerplant failed, he did not evacuate, but sheltered in place in his apartment in Fukushima City, 50 miles away from the powerplant. He started a Twitter feed of thoughts and observations, which soon had thousands of followers. Pebbles of Poetry 1, from Macrh 16, 2011, marks the very beginning of his posts and the moment when people were just becoming aware of the radiation leaks. On several occasions, Wago visited areas inside the evacuation zone, a 12-mile radius of the power plant. He wore a protective suit and a radiation monitor. His poem Screening Time was written after one of those visits. Wago’s writing addresses environmental degradation with an ecopoetics that not only explores the human toll of this catastrophe, but also includes the perspectives of cows abandoned in the fields; the fruits and crops left to waste; the once vibrant towns that now stand empty; and the soil, the ocean, and the air.

January 7, 2021, is one of a series of poems that Wago wrote marking ten years since the nuclear meltdown. It voices a more composed perspective on the memories and experiences of his earlier writings. It opens with a description of flying above the evacuation zone and includes a conversation with a dairy farmer forced to evacuate the area and abandon his herd. The poem integrates quotes from Wago’s twitter feed on March 22, 2011 in the first days following the meltdown; contextualizing, in this way, the original posts, integrating them with images and details to create an immersive sense of presence. Much of Wago’s work is dedicated to restoring Fukushima prefecture, not just in terms of environmental restoration, but also of the culture and lifestyle of the region and the well-being of future generations.

Ayako Takahashi and I have translated these poems collaboratively, working together weekly over video chat since 2017. Ayako tends to favor a more literal translation, while I am often most concerned that the translations work as poems. Our hope is that we have landed someplace in the middle, maintaining with fidelity the vitality of the original works.