TWO POEMS by C. Dale Young

FOR ITS BLUE FLICKERING

If you take cobalt as a simple salt

and dissolve it—if you dip a small metal loop

in such a solution and place it in a standard

flame, it burns a brilliant blue,

the flame itself bluer than the richest of skies

in summer. I wanted to be that blue.

And so, I claimed that element as my own,

imagined that fire could make of me

something bluer than the bluest of blues.

But what does an eighteen-year-old boy know

of the blues? All I knew then of cobalt

was its stable isotope. I had no knowledge

of the radioactive one with its gamma rays

used for decades to treat cancer. I had yet

to be exposed to such a thing. I was hot

for cobalt, for its blue flickering. Chemistry

can be such an odd thing. When a teacher of mine

offered up that faggots doused in certain chemicals

burned blue, I saw it as a sign; how can we

not see such things as signs, as omens?

Blue the waters of the Caribbean Sea,

blue the skies over the high deserts,

and blue the passages I found in old Greek texts

that surprised my prudish sense

of what men could do with men. It always

came back to blue. But boyish ideas are just that.

They seem for all the world to be fixed things,

when all they are is merely fleeting. In the end,

my make up was none other than anthracite,

something cold, dark, and difficult to ignite.

It is dense, only semi-lustrous, and hardly

noticeable. One dreams in cobalt, but one lives

in anthracite. Yes, the analogy is that basic.

Anthracite, one of earth’s studies in difficulty:

once lit it burns and burns. Caught somewhere

between ordinary coal and extraordinary graphite,

anthracite surprises when it burns. It isn’t flashy—

it produces a short, blue, and smokeless flame

that reminds one of the heart more than the sky.

PORTRAIT IN AZURE AND TWINE UNRAVELLING

Sometimes what attracts us is nothing more

than a marker of what is wrong with us.

Ravel was heralded as a genius, a master

of Impressionism, for his use of highly repetitive

structures, his rhythmic and repetitive structures.

Who can deny the beauty of Bolero? Not me.

As a child, I asked my mother to listen to me

while I practiced words like cobalt, each one more

and more odd for their sounds, their structures,

something I was still figuring out. “Grant us

Peace,” we repeated at Mass. Everything was repetitive.

And that is how it started, me trying to master

the language, the very words, fearful they would master

me, instead. Azure, sinecure, the long u had me

so early, and then the hard t one finds in repetitive,

substantive, titillation. I always needed more and more

words. Debussy once described Ravel as a man just like us,

one who understands that repetition structures

the way we move through the world, structures

our very breath, breath being that thing necessary to master

song, language, the natural world around us.

The first time I took a lover, she took time to watch me

sitting on the edge of the bed mouthing the word more.

After four hours, she dressed and called me repetitive,

told me the fun of it had ended, had become repetitive.

Memory, even when about something painful, structures

our worlds, structures our hearts and minds and more.

Within years of writing Bolero, Ravel could no longer master

music. He even lost the ability to use language. Imagine me

hearing this story. We were still new to each other, not yet us

but still a me and you. When Ravel left this world, left us,

you told me, many thought him mad and madly repetitive

pouring the same cup of water over and over. “Listen to me,”

you said. “Music is more than the simple structures

one need master.” I chose language instead of music to master,

all 171,000 words in the English language and more.

This morning, you caught me mouthing something other than more.

Ravel was not a man like us. Really. I just needed a new word to master.

My love, I’m repetitive. I sit here saying: “structures, structures, structures.”

Take Four: An Interview with C. Dale Young

In the second installment of our new interview series, “Take Four,” we talk to contributor C. Dale Young about his new work in short fiction, the subtle differences between poetry and prose, and the alchemy of characterization.

FWR: As an artistic mode, poetry seems to have served you well in the past. Was there anything in particular that turned your thoughts toward fiction?

CDY: First of all, thank you for saying poetry has served me well. Most of the time, I question whether or not I have served poetry well… I began writing with the belief I would be a fiction writer, a novelist. But I discovered poetry in college and found I had a better facility, a quicker facility, with it. I became discouraged about writing fiction. Later, as I began to publish more and more poems, fiction became something I remained interested in but then became afraid of writing for fear I’d look like an idiot. But I went to give a reading at Oregon State University six or seven years ago, and I did a roundtable discussion. It came up in the discussion, by the fiction writers there, that it seemed odd I didn’t write fiction. I think I laughed it off. But at that time, I had been trying to do something different with my poems, something requiring more than one voice, more than one mentality, and I was having real difficulties executing that. Maybe a better poet would have been able to do that, but I couldn’t.

On the way back to the airport, on a shuttle between Corvalis and Portland, this sentence came into my head: “No one would have believed him if he had tried to explain that he watched the man disappear.” I typically come up with the last lines of my poems first, but try as I did, this sentence did not seem like a line of one of my poems. I joked with myself, there on the shuttle bus, that maybe this was the start of a short story. So I poked around at the sentence in my head and then wrote it down on a piece of paper. As I looked at the sentence, I changed it to: “No one would have believed Ricardo Blanco if he had tried to explain that Javier Castillo could disappear.” I knew this was not a line from one of my poems, pulled out my laptop and typed the sentence. By the time I reached the airport, I had written about 700 words of this story that would become “The Affliction.”

I have no idea why at that moment I would start writing a story. And maybe I was able to start a story for years and years but never paid attention. I am not sure. But that story I wrote ended up prompting several other stories, some about the characters in “The Affliction,” some narrated by them, some about ancillary characters. That story opened a world for me that I haven’t really left yet.

FWR: As you mention, the character of Javier Castillo in your story “The Affliction” is literally able to disappear. In the end, he does so permanently. This is an interesting contrast to Leenck in “Between Men,” a character who also faces the prospect of literal disappearance, though in this case it’s decidedly against his will. What do you find attractive about the subject of disappearance, voluntary or not?

CDY: I have to be honest; I wasn’t aware of my attraction to disappearances. But now that you bring it up, it seems to exist in my poems as well. Several of the poems I have written in the last 7 years have this idea of disappearing in them. I guess that isn’t so odd seeing these stories were written in the same time period. But wow, I wasn’t aware of that until you just brought it up.

In my day to day life as a physician, as an oncologist, I am keenly aware of people disappearing. Some fight until the end of their lives to stay present, and others give up and disappear long before their physical bodies do. The ways in which the mind deals with mortality have always interested me, and it occurs to me now that my attraction to this idea of disappearance might stem from my own mind working this out. I am not entirely sure, though you have given me much to think about!

FWR: When writers talk about the differences between poetry and fiction, there’s often some “grass is greener” mentality on both sides of the fence. As well as a lot of wondering whether or not “crossing over” is even possible. Having had some experience with both, do you think there’s really as much difference between the forms as we seem to think there is?

CDY: Well, we all, poets and fiction writers, come from the same heritage, the epic poem. Some forget that in the scope of literary history, the novel is a fairly new thing. Both poets and fiction writers, in order to do what we do well, must not only tell a story but create an experience, or the sense that one as a reader is enmeshed in the experience. Lyric poetry tries to provide a flash of an experience, something brief and intense. Most fiction provides a more gradual enveloping of the reader into the world of the story or the novel. Many of our tools are the same. But the genres are different. Their ways of captivating readers are different. At base, the tools might be similar or the same, but the execution of the writing and the goals of the writing are usually different. I guess what I am saying is that poets have much to learn from fiction writers. Studying fiction allows them to better see the speaker of a poem as a created thing akin to a character in a novel. And fiction writers have much to learn from poets. Studying poetry allows them to better use figuration, to set scene with a keen eye, etc. Some “cross over” to use your phrase. Many will never feel a desire to do both.

FWR: In an interview for the American Literary Review you said that you once “…falsely believed that the love poem was in essence a dead form… What I realized with time is that the love poem isn’t dead but just incredibly difficult to pull off…” Both “The Affliction” and “Between Men” evoke beautifully complicated forms of love. Do you think love stories are just as difficult? What do you think makes these particular stories work?

CDY: I suspect the love story is also a “dead form.” Like the love poem, one must be ever vigilant when writing a love story to avoid the trap of cliché. This is incredibly difficult. I don’t think of “The Affliction” as a love story. I suspect I actually think of it more as a falling out of love story, which is just as dangerous. I didn’t conceive of “Between Men” as a love story, and I resist the idea of it being a love story. But I do see why you would raise the issue. In many ways, Leenck wants to love Carlos but cannot. And yet, in the end, it is his love for Carlos, in whatever form, that does him in. As for what makes these stories work? A little bit of hard work and a lot of alchemy. A lot of alchemy.

FWR: Alchemy. That’s an interesting word. I think you’d agree that stories often start to cohere at the moment their characters – and their characters’ relationships to one another – become complex or detailed enough to give the story life. Have you ever been surprised by one of these moments?

CDY: I have. These moments have happened to me countless times over the years, both in writing poems and stories. In the two stories you mentioned, one spawned the other. The narrator of “The Affliction” is the Carlos in “Between Men.” My desire to “know more” about Carlos led me to this story. And the sons and wife of Javier Castillo end up having their own stories. And even the most recent story I drafted examines one of Javier’s sons who is locked up in a ward for mentally unstable people who have committed crimes. This discovery of the person within and behind the story is what keeps me going back to the writing. I need to know, and that need is what many times generates the story. The story might start with an image or a sentence or a realization in my head, but the stories always move forward as I figure out the characters, what motivates them. It is funny, but Carlos, Javier, Leenck, Flora Diaz, these characters I know I created, seem to me, at times, very real people, something that must have come not from inside but from without. And that is alchemy to me; something not magical, perhaps, but close to it.

|

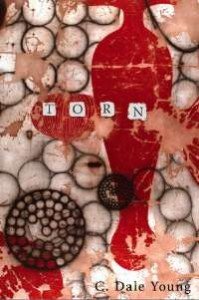

“With clarity and precision, the poems uncover the secrets of blood and lust and heart, the nature of selfhood, and the accompanying larger social and political implications of identity. Beneath all this is a quest for beauty and evidence of the poet’s deeply humane intelligence and the breadth of his sensibilities.” —Natasha Trethewey

“Between Men,” by C. Dale Young

|

|

More Interviews |

BETWEEN MEN by C. Dale Young

You never know you want to live until someone tells you that you will die. For four years, Leenck had worked from home processing accounts for an investment firm. Leenck was dying. Suffice it to say, he was painfully aware now that he was dying. He had already gone to the bank and withdrawn all of his savings: at the counter waiting for this manager or that supervisor to sign this or that form, the teller had looked at him that morning as if she knew, as if she, too, knew he was dying. It was as if everyone were staring at him. When Leenck arrived at his home, he telephoned his lawyer and told him to find a house for him to rent in Santa Monica, a small house near the beach, a house where no one would notice him. And within a few days, Leenck packed some of his clothes in a duffle bag and drove to the new place. It was that simple. He had no family in the U.S. His family had written him off for dead ages ago. He had no one who would notice him missing. His co-workers didn’t even know what he looked like.

Leenck had no intention of getting to know Santa Monica. What he knew of it he knew by driving through it on his way to the new house, a place described in the real estate ad as a charming bungalow. One bedroom and one bathroom, a living room, a small kitchen, a patio and a strangely large yard, and still the new place seemed enormous to him, larger than he felt he deserved. The house came partially furnished. It had no table and chairs in the kitchen, and there was no dining area. The same yellow linoleum covered the floors in both the kitchen and the dining room. It was yellow, though it was easy to tell it had once been off-white. If one wanted to eat, such a thing would have to be done standing in the kitchen or sitting on the couch with the coffee table functioning as dining table. But there was a bed, a couch, said coffee table, and a plastic lounge chair in the back yard. There were overhead lights but no lamps, and Leenck had no intention of remedying that fact. The beach was exactly an eight-minute walk away. And despite wanting to stay locked up inside the house, Leenck found himself walking down to the beach twice a day. It became a habit for him, a kind of pilgrimage. It was always the same. He would walk down his street, make a left-hand turn, and walk over the pedestrian bridge to the beach. Sometimes, he would walk on the pier, but mostly he just walked or stood on the sand.

Orange juice and sparkling wine: what more could one desire for breakfast? Each morning, Leenck drank a cup of instant coffee and then filled a tumbler with ice followed with a quarter glass of orange juice and the remaining three quarters of the glass with sparkling wine. The walk to the beach then followed. On some days, he would even forego the coffee. There were times when he would stay at the beach for hours. On other occasions, he would walk around for fifteen minutes and then walk home. He saw some of the same people at the beach almost daily. There was the old man who always wore pastel blues and pinks who sat on the rotting bench eating a bagel each morning. He was a man of few expressions. There was glum and glummer with only a mild change in his face as he ate the bagel. And there was the Chinese woman who did stretches and quick jabbing movements with her hands, jabbing at the air as if at birds only she could see, birds attacking her. There was the homeless man who wandered aimlessly muttering something about cats and cleanliness. There was the young woman briskly walking her small dog, a dog that always appeared better groomed than she did, at least four pink or red ribbons in its fur as if the mane on its head were in fact a hairstyle. The sun would be far behind them all, on the other side of the city. There would be light in the sky, but no sun. The sand would be a filthy grey dotted with trash, but at least the trash changed daily. The ocean would be there with its insistent noise and smell. At least there was this one constant. Leenck knew what he would find at the beach. He knew what each day brought. And each morning, on his walk, he wondered if his final day had come, if that very day was the one.

Some people, when faced with death, find themselves possessed with an undeniable urge to do things, to do everything they had ever wanted to do but had never found the time. They travel to distant lands. They jump off of bridges into murky water. They rappel down cliffs, fly in helicopters, dive in shark-infested waters, venture out on walking safaris in the bush hoping to hear the Lion’s unmistakable grumbling roar. They live and live dangerously because they know they are about to die. But Leenck was not one of those people. He wanted to die privately. He was absolutely certain about this. He wanted to die alone. He wanted to disappear the way an actor playing the Buddha might in an old movie.

“Hey man. You okay?” The voice startled Leenck, even though he had no idea what the man had just said to him. He turned around and stared at the man.

“I’ve seen you out here before. Man, you almost walked into that garbage can.”

“Oh. Sorry. I was just thinking. Sorry.”

“No problem, man. I do that sometimes, too. I’m Carlos. Carlos.”

“Hi Carlos, Carlos.”

Leenck was always amazed at the way Americans could just strike up conversations, how they always seemed to want to talk. Leenck believed that silence bothered Americans. And yet, this was the first time anyone had spoken to him at the beach. Leenck mumbled a few more things and said he had to get going. On the way home, Leenck wondered why this man had talked to him. Once home, Leenck went out on the patio, sat in his single lounge chair and fell asleep. When he woke up, it was already late afternoon. It was time again to return to the beach. On the walk to the beach this time, Leenck noticed the creamsicle-colored blooms of the hibiscus in various yards. He wondered why anyone would plant such odd plants. He could hear the crackling of the telephone wires overhead once he made the turn toward the beach, knew that the humidity must be fairly high that afternoon. Slowly, he found himself filled with anxiety that Carlos would still be there. He was worried that maybe even someone else might talk to him. And so he stopped, turned around, and walked back to the house.

************************************

“When did the pain start? What did you first notice?”

“I fell off of my bike a few weeks ago, and ever since then I have been sore.”

“Where are you sore?”

“Here.” Leenck pointed to his left side just where he felt the last of his rib bones just under the skin.

“Did you take anything for it?”

“I took some Advil, and it helped a little. But I think I broke a rib.”

“Well, we will take a look. But this doesn’t sound like a broken rib. Sounds as if you bruised a muscle there.” The doctor emphasized the word “bruised” as if Leenck might not have noticed the word otherwise. He had a way of emphasizing words that made Leenck feel as if he were a complete idiot.

Leenck did not like doctors. In the old country, in the town where he grew up, there were no doctors. There was the old woman who was the teacher. She knew how to help people. She would touch you and tell you things about what hurt you. But these American doctors, they barely ever touched you. And when they did, they wore gloves as if they were handling raw meat. Doctor Peterson was probably a nice man, but to Leenck he was distant and calculating. He said little besides asking his various questions and, honestly, he had only seen him once or twice. Despite his distrust, Leenck always did what the doctor said. He took the pills three times a day. Even when they made him nauseous, he took them. He tried taking them with milk or when he ate something, but it didn’t really help. He took the pills for two weeks, and they didn’t help in the slightest. They only gave him a dry mouth and a sometimes-dizzy feeling in his head. When he returned to the clinic, the doctor seemed surprised that the pills hadn’t worked. He sent Leenck for a CT Scan. Leenck sat in the waiting room outside the radiology department. And then he sat in a smaller waiting room inside. And then a nurse took him into the room with the giant donut-shaped scanner, placed a needle in his arm and had him lie down on the table, the room smelling a little like burning rubber. Above his head, he could see a red light on the top of the large ring that encircled the table. The table inched though the ring and then slid back out, the light sometimes green and sometimes red. And then, he felt the warmth of something rushing through the needle and into his arm, and then he felt the table inching through the giant donut a little more. Ten minutes later, a young man told Leenck his spleen was very large and that he needed to call Doctor Peterson immediately.

For Leenck, that was not the beginning but the end. He called Doctor Peterson. He did more tests, had blood drawn, suffered through seeing a woman doctor who rammed a large bore needle into his hip and pulled bloody fluid out into a syringe. He was warned of the pain but felt nothing. He was 36 years old, and he was dying. This is all he could remember about the woman doctor. He couldn’t even remember her name.

************************************

Leenck hated the grocery store. There were just too many people darting around grabbing things and throwing them in carts: too many people talking to themselves about what they needed to pick up, how many, what size, etc. It irritated him to see people like this. It irritated him when people spoke to themselves out loud. He felt it was a weakness of some type, a weak mind. He wanted to order groceries and have them delivered, but that would mean having to set up phone service. And this was unthinkable to Leenck. Phone service, connection: what was the point? But he needed orange juice and more sparkling wine. He knew exactly where they were in the grocery store. He bought the most expensive orange juice and the least expensive sparkling wine. As Leenck walked down the aisle toward the produce where the orange juices were shelved in a refrigerator, he saw Carlos. Leenck knew that Carlos also saw him and wondered how he might turn without making an incident. But it was too late.

“Hey, you the guy from the beach. We talked. I’m Carlos.”

Leenck knew exactly who Carlos was. In fact, Carlos was the only person Leenck had seen who had dared to disturb him.

“I don’t think you ever told me your name.”

“Leenck.”

“Is that Scandinavian?”

“You know, I am not really sure. My parents weren’t Scandinavian. But they aren’t around for me to ask them.”

Leenck had both told the truth and lied in the same breath. His parents were in the old country, but they were very much alive despite the fact Leenck made it sound as if they were dead.

“Oh, sorry about that. My folks are gone now, too.”

Leenck was trying to walk away now, but Carlos followed. Carlos was talking about his family and how he had lived in the U.S. for so long now.

“You are not American?” Leenck asked.

“Oh no.” Carlos laughed. “I grew up on a small island in the Caribbean. My father’s family is from Spain. My mother’s family was Spanish and Indian.”

“But you don’t have much of an accent?”

“Neither do you…”

Leenck had reached the checkout and became aware now that all he had was the sparkling wine and the orange juice. He grabbed a TV Guide and threw it on the belt along with the beverages. But Leenck had no television, and he couldn’t explain why he had done that, not even to himself. When he paid for his items, he nodded at Carlos.

“Good talking with you, man. Maybe we’ll run into each other again.”

“Yeah. Maybe. Yeah. “ Leenck was already worried he would see Carlos again.

At home, Leenck fixed himself a tumbler of mimosa. He drank it all in one sitting and fixed himself another to sip while sitting in the back yard. The grass was withering in various places, but lush and green in others. The yard looked like a patchwork of greens and decay. The fence was unpainted on the side he could see. From outside his yard, the fence was white, almost pristine. But inside the yard, it was an unstained and unpainted fence that looked like it was rotting. The water from the sprinklers had given the fence a reddish rusty complexion. Leenck thought about his parents. And then, he said out loud “No, they are not Scandinavian. They are most certainly not Scandinavian.”

************************************

“You have a leukemia. This is a cancer of your white blood cells.”

“How do we get rid of it?”

“Well, we can try to control it with chemotherapy…”

“What?”

“Chemotherapy. Drugs that will kill off some of your cancer cells.”

“But you said control it. You cannot get rid of it?”

“No, this is a chronic leukemia. We cannot cure it.”

“So, I’m going to die of this.”

“Well some people live a very long time with this.”

“What is a long time? What does this mean for me now?”

“Right now, we just need to focus on the diagnosis and getting started with chemotherapy.”

“But… But, this is…”

“But nothing. We need to get started because your spleen is filled with cancer cells.”

“I just need some time to think about this.”

“We need to get started. You don’t have a lot of time to think about this…”

************************************

Leenck woke to find himself scratching the scar he had on his left leg. It had been a long time since he thought about this scar or how he got it. And it seemed as if it were all a dream, the way he had tried to impress his father by tying a wire around his leg to show how far up a tree limb one should tie it off before cutting it. But it wasn’t a dream, and the scar reminded him of that, reminded him of the old country and the simple way of life in which he had been raised. To Leenck, he had not been raised in a cult but just raised differently, raised to understand a more simple way of life. And he wondered about his parents, wondered if they were still alive. But Leenck knew they were alive. People in his family lived into their 90’s if they were needed in the town. Yes, they were alive. He knew they had to be alive. He could practically see them doing their every day routines when he closed his eyes.

Leenck got up and went into the kitchen and made some instant coffee. He drank it quickly and made himself a mimosa. He took the drink out on to his backyard patio and sat there in his boxer shorts. The fence was definitely rotting. He swore he could almost smell the wood rotting. And he got up and started walking around the backyard barefoot. Leenck walked around and around the backyard in circles. And when he got tired, he stopped and took off his boxer shorts and threw them on the ground. He stood there naked sipping mimosa from his tumbler with the sunlight warming his entire body. He stretched his arms and back. He slowly turned around and around inspecting the rotting and hideous fence. He walked over to it and started walking along it around the yard. As he walked along the eastern edge of the yard he noticed one of the boards in the fence was loose and hanging at a slight angle. He had no idea why he wanted to look through the space opened in the fence. Call it a childish curiosity. Leenck lowered himself on one knee and looked through the crack into his next-door-neighbor’s yard. Lying on a towel on the grass in a pair of tight square swimming trunks was Carlos. Carlos lived next door. Leenck bolted upright, ran over to his boxers and picked them up before running into his house and closing the glass sliding door behind him. He leaned against the glass door and downed the rest of his mimosa. He put his boxer shorts back on. He made himself another mimosa. That man from the beach, from the grocery store, Carlos, lived next door. To Leenck, this was just not possible. To Leenck, this was a terrible joke.

************************************

“This is Sheila from Dr. Weiss’s office calling for Leenck Woods. Please call us when you get this message. Dr. Weiss feels it is very important for you to come in for your treatments. We have left several messages for you, and the doctor is concerned. Please, if you have any questions or concerns about your treatments, please call us so you can speak to one of our nurses.”

This was the last message Leenck heard on his answering machine before he left Los Angeles. He had screened his calls for several days after he attended his chemotherapy training sessions. Poison. He believed they wanted to poison him. Not in the nefarious way they do in a movie, all plotting and scheming and then the fatal scene with a woman, always a woman, standing over someone. No, not like that, but he knew that chemotherapy was merely poison. He wasn’t going do it. He couldn’t get himself to do it. He had decided to die. He had already gotten the house to rent in Santa Monica. He had already sold off all of his stocks and bonds and withdrawn all of his money from his various accounts. As he walked out the front door, Leenck spoke out loud: “This is Leenck from the Office of the Dying. I feel it is very important for me to die, and am therefore refusing chemotherapy.” He stopped and thought about what he said. “Hmmm. Maybe I should phrase it differently… This is Mr. Woods. I have opted not to receive the treatment.” As he said this he closed the door behind him. The power would be turned off that afternoon. He had no intention of ever calling Dr. Weiss’s office. He never did.

************************************

“You live next door to me.”

“Yeah.”

“Is that why you talked to me here that morning?”

“No man, I talked to you because you looked down and you almost walked into a garbage can.”

“But you knew I lived next door to you.”

“Yeah, I saw when you moved in. You didn’t bring much with you.”

Leenck looked down the beach beyond Carlos who was sitting on a bench in front of him. Some children were throwing a Frisbee and yelling “Fuck!” every time one of them didn’t catch it.

“Why didn’t you say anything?”

“About what? About living next door?”

“Yes, why didn’t you…”

“Look man, when I first met you, you didn’t seem to want to talk. You practically ran away.”

Leenck turned and started walking away. In the distance, he heard, once again, “Fuck!”

“What is up with you, man? Is it a bad thing that I live next door?” Carlos yelled as Leenck was already a good fifteen feet away from him.

Leenck didn’t answer, nor did he stop walking.

“I know you are sick.”

Leenck stopped and turned around. “What?”

“Dude, I know you a sick muthafucker. You drink all day long.”

Leenck didn’t respond. He stared at Carlos and then turned and began walking again.

“I’m just kidding with you, man. Jesus. What’s up with you? I’m just joking with you.”

“I’m sick. I’m really sick.”

Another of the Frisbee kids yelled “Fuck!” followed by “This Frisbee is fucked up!” followed by “Who the fuck even makes this shit ass Frisbee!”

Leenck had no idea why he had admitted to Carlos that he was sick. He just kept walking. He had not told anyone he was sick, and Carlos was the last person on earth he had imagined telling this particular fact. It took him about 8 minutes to get to his house. He felt feverish. He felt warm, flushed almost. When he got to his kitchen, he fixed himself a mimosa. He felt sweaty and now the fever seemed to be consuming him. He took off his shirt and realized it was wet with sweat. He had walked home slowly, so he hadn’t expected this. He stripped down in the kitchen to his underwear. Sweat ran down his temples. As he walked into the living room, the doorbell rang. Leenck wasn’t thinking. He opened the door to find Carlos staring at him. Leenck stood in his own doorway half naked and covered in sweat. He swayed slightly while standing there. He knew then that he was collapsing. It started in his knees. And then he felt his hand gripping the door. And then, and then he woke up on the couch.

“You okay, man?”

“What?”

“You passed out cold, man. You just fell.”

“Where? Where am…”

“You’re on your couch. I caught you before you hit the floor, man. I carried you over here.”

“Get out.”

“Wow, you’re a really thankful guy.”

“Seriously, you have to get out.”

“What, you think I never seen a guy in his underwear?”

“You need to…”

“Man, I was joking about you being sick and all. But you really are sick. You need to see a doctor.”

“I have already been to doctors.”

“But you sick and should probably see a new doctor.”

“I am sick. And I’m dying.”

“That’s just the sickness talking smack, man.”

“No, listen to me. Everything dies, and now I am dying.” Leenck surprised himself with this statement. It sounded almost as if now he were in a movie reciting a script. The poison had set in and in the next scene he would be clutching his chest while he vomited up yellow-green foam. He knew this was melodrama, but he could not stop himself.

Carlos looked at Leenck with the deepest concern on his brow: “I know an old woman. You need to go see the old woman, Cassie. She can help you.”

“No one can help me.” Again, Leenck marveled at the drama of his short outbursts, declaimed as if he were on a stage. Why, he thought, was he speaking like this?

“Cassie can. She cures all kinds of people. I can take you to her. She lives not far from where I grew up. All we have to do is fly to Antigua and then charter a boat.”

“I’m not going anywhere.”

Days later, Leenck felt better. The sweats had passed. He got up, showered, and went outside. He pulled the plastic lounge chair from out of the shade and positioned it at the bottom of the few steps to the patio, positioned it in direct sunlight and then lay down on it.

“Why you all naked in your backyard, you perv?” came the voice from the other side of the fence.

“Why are you looking through a crack in the fence into my backyard? So, who’s the pervert?”

Carlos laughed when he heard this. “Man should be able to do what he wants in his own place.”

Before Leenck could answer, Carlos had climbed over the fence into the backyard. “You okay, man?”

“I’m fine. I didn’t collapse or anything. I walked out here and can walk back inside.”

Carlos walked over and sat down on the steps to Leenck’s patio just behind him.

“Do you often sit down with your neighbor when he’s completely naked in his backyard?”

“You’re the one who’s naked!” Carlos responded.

“But it is my backyard, my own place. Remember? Man should be able to do what he wants in his own place.” When he said this, he mimicked Carlos and the pattern of his speech, but Carlos did not seem to mind.

“I don’t got a problem with you being naked. If you want I can turn away or get something to cover you.”

“Doesn’t matter. Nothing exciting here. Just an average guy.”

“Yeah, you not a porn star or anything.” They both started laughing. “Have you thought about what I said?”

“About what, my not being a porn star?”

“Cassie, the old woman. Will you let me take you to see Old Cassie?”

“Why would I do that?”

“Because she can cure you. She has been curing people of all kinds of disease for as long as I can remember. Scary old woman, gifted healer.”

“She can’t help me with what I have.”

“She has cured people of heart disease, diabetes, MS, even Alzheimers. She even cures people of cancer.” Carlos watched to see Leenck’s response. There was none.

“She can’t help…”

“What is wrong with you, man? What do you have?”

“It isn’t important. I just know she can’t help me.”

Leenck got up and walked up the steps past Carlos and into the house. As he stood in his kitchen mixing a mimosa, Carlos came inside.

“Ah, your vice.”

“Drinking naked?”

“Nah, just the drinking.”

“You’re gay, aren’t you, Carlos?”

“Yeah, why?”

“Most guys wouldn’t casually talk to another guy who is naked and drinking in his kitchen.”

“You gay?”

“No, Carlos. Not gay.”

“Then how did you know I was gay?”

“This is California, Carlos…”

“Oh man, I’m not coming on to you or anything.”

“I didn’t think you were. It is just that my being naked didn’t bother you. And you have helped me and worried about me. Most men don’t give a shit about other men.”

For the first time since they had met, Carlos felt uncomfortable and embarrassed. He could tell the blood was rushing to his face and could feel the warmth of it in his cheeks. “I think I better go.”

Leenck could see Carlos blushing, and something inside him enjoyed the discomfort he was producing in Carlos: “Why, because I am standing here with no clothes on? Because you keep checking out my dick? I might not be a porn star, but I can see you checking me out.”

“Man, your skinny ass self ain’t all that… I gotta go, man.”

“Why, you getting turned on? You want some of this?”

“No, because there is something wrong with you, man. You not right.”

************************************

“We need to get started with chemotherapy.”

“Shouldn’t we run another test? I mean, are you 100% sure?”

“Yes, we are sure. I have scheduled you for your chemo class tomorrow. We really need to get going on this.”

“How long do I have?”

“I just don’t have an answer for that.” As usual, when she said this, the doctor turned away from Leenck and refused to look him in the face.

“What if I do nothing? What if I don’t do the chemotherapy?”

“Then you’ll die.” The doctor said this with a matter-of-fact tone that seemed to Leenck almost graceful. There wasn’t even the slightest change in the expression on her face, which remained flat and virtually blank. She stood up from her chair and walked over to a sink and washed her hands. Leenck found this strange seeing she hadn’t examined him while she had been in the room. But he knew it was likely just another way for her to avoid looking at him.

“But even if I do the chemo I will eventually die, right?”

“Well, we all eventually die. But you don’t want to die like this.”

“Maybe the lab test is a mistake.”

“It is not a mistake. We have gone over this already.”

Leenck could hear the growing frustration in his doctor’s voice. He decided to simply agree with her. He would go to the chemo class. He would tell her what she wanted to hear. Leenck knew he was good at that, good at telling people what they wanted to hear. He had been doing that for his entire life.

************************************

From the boat, Leenck could see the darkness of the island in the distance then the island itself. It had been six months since he first met Carlos. Now, here he was sailing to some small island near Antigua. There were too many shades of blue in the ocean between him and the island. Each seemed like a different possibility. Carlos was inside the cabin talking to the captain. He knew what Carlos wanted him to do. He wanted him to go see the old healer woman who could make different illnesses disappear. But Leenck was afraid. He wasn’t afraid of the woman, but afraid of what she might do to him.

As the ship pulled closer and closer to island, he could make out the harbor and the various boats and small ships anchored there. There was the blue water and the white and blue boats. There were the houses on the hillside in a gaudy array of colors: flamingo pinks and crayon greens, odd teals and purples. As the boat approached the island, Leenck remembered his father crying in their house back in the old country. He remembered telling his father that he was not a carpenter and that he was not cut out to be a carpenter, that he was leaving the town and that way of life. And he remembered his father begging him not to do it, begging him to reconsider. His father told him that he would die from the inside out if he left their way of life. And now Leenck wondered if that wasn’t exactly what was happening. He had blood cells going crazy in his body. The cells were moving all through his body. From the inside out. His father had been right. He was dying from the inside out.

Why does a man think this way at the end? Why does he see in the past the glimmers of prophecy that likely were never meant to be prophecy? It is hard to say why. But Leenck saw now in his father’s last words to him the overwhelming power of prophecy. And those words repeated over and over in his head: “dying from the inside out.” And besides this prophecy, there was Carlos. Leenck knew Carlos had fallen in love with him, loved him, was deeply in love with him. He knew it. Leenck also knew he didn’t love Carlos that way and could never love Carlos that way. Sex with a man just didn’t seem like his kind of thing. And loving a man? That was beyond Leenck’s comprehension. He would likely have had an easier time having sex with Carlos than loving Carlos. Carlos was his friend, despite the fact he wanted no friends. And even then, Leenck could not decide if he even cared for Carlos as a friend. But Leenck knew he let Carlos love him, allowed him to fall in love with him. It was one of the few things Leenck could admit to himself. He allowed Carlos to fall in love with him, and he had no idea why he had allowed that.

“Nickel for your thoughts,” Carlos said while looking beyond Leenck at the island coming into focus.

“Nothing, really.”

“We should be ashore within a half an hour. My cousin has already arranged for Cassie to see us.”

“Oh?”

“She is a really weird old woman. Man, the stories about her are legendary.”

“She’s still just a woman.”

“Some think she is a god.”

“I’m not sure I want to meet a god.”

“Well, you’ll see when you meet her.”

“I’m not going to meet her.”

“Man, what the hell you talking about?”

“I’m not going to meet her. I told you I would come with you, but I never said I would go see the old woman.”

“Leenck, you’re getting sicker. You’ve lost twenty pounds or more since I met you.”

“I wanted to see the island. I wanted to make the trip. I wanted to leave the U.S.”

“You can’t come this far and not see her, man.”

Carlos turned away from Leenck and walked back inside. As he got inside, he saw himself in a mirror and suddenly wanted to laugh. “Who was the sick muthafucker?” he thought, “Who is the real sick one here?” As he stared at the mirror, he became more and more angry. The captain’s assistant was saying something to him, but he couldn’t hear him. Outside, the harbor was calm. There was almost no breeze skimming across it. The sky was overcast now. And out the porthole window, Carlos could see the mountain and trees that marked this place as his home, the place where he grew up. He went back up on deck to Leenck.

“Please, just meet the woman. Talk to her. You don’t have to do anything else…”

“Carlos, I am already dead.”

“Stop being crazy. Why you always have to be crazy?”

“Don’t you see? Don’t you see it? It caught up to me. It has been with me for so long that it has finally overcome me. I’ve been dying for my entire adult life. I just didn’t see it.”

“Please, Leenck, the boat is docked. Stop the drama. Just come see the old woman.”

“I won’t. I will not. I cannot leave the boat.”

“Don’t do this, Leenck. Don’t…”

“I have already done it.”

The water was getting dark in the harbor under the overcast sky. The clouds were gray and looked like dark dishwater. The air was unusually still. And Leenck waited for the tears in Carlos’ eyes. But the tears didn’t come. Leenck knew Carlos would cry. He wanted him to cry. And why he wanted this he couldn’t even explain to himself. But he wanted it, wanted this man in front of him to drop to his knees and beg him to go see the old woman, the tears streaming down his face. It would come to that. Leenck was sure of it.

The sky looked as if, at any moment, there would be thunder. The clouds darkened and darkened. The water of the harbor became a steely gray darker than the dishwater clouds above it. And Carlos turned from Leenck and made his way on to the dock. He did not turn back. He did not look back. He walked away at a slow and steady pace. And Leenck sat there coughing while seagulls scurried around on the dock fighting and arguing over garbage. And then the wind came back, the wind picked up, the wind suddenly sweeping the crushed plastic cups from the dock and into the water. And instead of thunder, all Leenck heard was the sound of palm trees, their fronds rustling in the distance, hundreds of palm trees tilting their fronds like flags in the wind. Leenck could see Carlos in the distance now, the tiny outline of him. He watched the outline to see if Carlos would turn around to look for him on the boat. He wondered if Carlos was now crying. Leenck felt tired, and he felt odd, his chest heaving more so than normal. He watched the tiny outline of Carlos get smaller and smaller. And then he could no longer make him out. And he knew he had not turned to look back at him. And then, tears surprised Leenck’s face. The tears came quickly and frightened him. Not once had he cried in the past twenty years. And the harbor got even darker. And his eyes stung. There was not a single rumble of thunder, just the breeze rustling the palm trees and the seagulls going mad over debris. The rain came down. It was forceful, cool and prickly as it hit him in the head and face. He thought he should move inside the cabin, but he sat there instead. He didn’t move. He was completely wet now, the tears on his face indistinguishable now. His chest tightened in a way he had never experienced in his life. The rain pelted everything, and the deck suddenly took on the dark stain of the rainwater, a stain not quite as dark as the heart, a stain not quite as dark as blood. Leenck stared toward the mountain trying to make out Carlos. But he could no longer make him out. His chest was heaving as the sobs escaped his own mouth. He looked at the door of the cabin and saw the Captain staring at him, and Leenck knew he was laughing at him, chuckling. But Leenck continued to sob. His head more and more dizzy, his chest tight and painful. And then he realized he was on his knees. And the trees in the distance seemed to be bluring into the rest of the landscape, everything bleeding together. And again, he looked for the figure of Carlos. On his knees, sobbing, Leenck felt his chest tighten even more. He looked for Carlos, but he couldn’t make him out. He kept looking for Carlos.