SATURDAYS AT THE PHILHARMONIC by Megan Staffel

Patsy Smith left Rochester, New York on a sunny Saturday morning intending to drive all the way to California. But after three and a half hours, crossing through an Indian reservation, she got lost. On a long, straight road, where there hadn’t been a route number for many miles, there was a sudden break in the forest and she saw a small building with cars and trucks parked in front. She turned in to ask directions.

Pulling the door open, she smelled beer. She saw men with their backs to her sitting at the end of a room on bar stools, and close by, a few small tables and chairs that were mostly empty. The door snapped shut behind her and in the sudden darkness all she could make out were the neon beer signs. She stood still, waiting until her eyes adjusted. It was nineteen sixty-eight. Patsy was sixteen. She had an old car, a hundred dollars, a pillow, a blanket, a pair of broken-in lace-up boots; that was the total of her possessions. But it was all she needed.

The man sitting at the table closest to her was the only one who had seen her come in. He stared at the girl with bare feet, filthy pants, long curly hair, and a wide pale face that even at that moment in a strange place, had an oddly quixotic expression.

Patsy was remembering a fact from seventh grade New York State history. These Indians, the Seneca, were called Keepers of the Western Door. They were protectors. Maybe that was why she had chosen the route that went through their reservation, and now, having lost it, maybe that was why she felt so confident standing in the smoky room.

The men at the bar, a row of dark backs with dark heads, talked quietly. When her eyes adjusted, she saw the man sitting by himself at the closest table. A shaft of light, coming from a small window, settled on his shoulders and made the rest of the room unimportant.

Patsy Smith stayed by the door, covered in shadow, but lit up, inside, by the beam of the lone drinker’s attention. She had left her home in a rush and on this first afternoon that she was on her own, she could already see that when she was away from her family, she, as a separate and independent person, would matter. The man in the light was slowly standing up. He didn’t look at her, but she knew she was the reason he’d gotten to his feet, and not the bathroom or some peppery old geezer sitting at the bar.

“Help you?” he asked.

It was not a friendly face. It was too hard for that. But he looked at her straight on, the raw flat angles of his cheeks glistening.

“Did I miss a turnoff or something? Route seventeen? I think I lost it.”

There was a flicker of amusement at the corners of his mouth and he said very slowly but in a proud tone, “You most certainly did. This is the beginning of the end of everything you could call familiar. So why not stay for awhile?”

Her warning system had been defused long ago. So it didn’t make her nervous to be the only woman in a room of stoop shouldered old men with a younger one who spoke in riddles; in fact, it sent an excited shiver down her spine. She joined him at his table and had a beer. And when he asked her a question, she told him a few things about herself: that she was going to California, that she had major plans, that she didn’t know exactly where in California, but that was only a detail. He told her about Handsome Lake.

“He’s the prophet who saved the Seneca from the white man. His visions restored our people.”

“Handsome Lake,” she repeated, her brain foggy from beer on an empty stomach. “That’s not your name, right, that’s someone else?”

“Someone else.”

“Well I’m Patsy Smith.” She extended her hand, aiming all of her enthusiasm into his dark, simmering eyes.

“Uly Jojockety.” He said it softly and without any salesmanship, but he did offer his hand, and when she took it, she could feel the dry grittiness of his palm and realized how far she was from the land where people with soft palms named Smith ruled over her.

“So who is this Handsome Lake? Does he have a Bible, sort of, or a radio program?”

He laughed. “No, this was long ago, 1799.”

“You’re kidding.” The way he’d spoken she’d thought it was now. “So…how do you know about him?”

“You see, we’re not like you. What we have is a straight line that goes from this day now to his first vision in 1799. The now, the here,” he touched the top of the table, “it rests on what happened before.”

“That’s really far out,” she said, thinking to herself that you might want to remember old Indians, but old white men it was probably better to forget.

Sometime later, she left him to go outside to pee. And while squatting behind the building, her ass visible to anyone who might walk past the row of trash cans, she was startled by a crackle of leaves and looked up. There he was, looming over her, his face more craggy from the ground up. Apparently, a lady’s bare squat didn’t prohibit a man’s gaze.

“No need to be embarrassed. Nothing new about a woman pissing.”

She pulled her jeans upwards, careless about what he might see, and he said, “but girls from Rochester, now I thought they only used toilets.”

She was stung by that word, girls. “Some maybe,” she answered, “not me. I’ve been doing this forever.”

She had her third beer leaning against the trunk of a cottonwood that was as ancient probably as the events he spoke of. He told her about the United States government stealing ten thousand acres of the most fertile Seneca land, river land that had been protected since 1794, in a treaty signed by General George Washington himself, how they’d removed his family and a thousand others. Just to build a dam that could have been built somewheres else. But no, Indian land was their choice. The good people of Pittsburgh, three hundred miles away, needed protection, by the US government, from the inconvenience of high waters in the spring.

“They burnt our house down, cut our trees, gave us a handful of dollars, and stuck us in a little white box with all the modern conveniences we didn’t want. They took it all. No more fish, no more fields, no more forests, no more longhouse. No wait,” he held up a finger, “let me be fair, they moved the longhouse. So then they said, what do you Indians have to gripe about? Okay? What do you Indians have to gripe about? And now do you know what they’re saying? They’re saying, wait and see, we’re going to lay route 17 right through your reservation and cut it in half. You saw how it stopped, right?”

“It just sort of disappeared,” she said. “And then all these little roads you were supposed to follow were really confusing and I got lost.”

“Exactly. That’s because we will not let a foreign government make a highway through our land.” With his hand on his chest, he intoned in a solemn voice, “I pledge allegiance to the Seneca Nation to frustrate the United States Traveler forever and ever.”

She laughed, happy to collude in such vehement anti-establishment feelings.

The sun was sinking. Rays of light were scattered by the leaves that laced the blueness of the afternoon. She knew she was drunk. But only partially was it alcohol. The rest of her euphoria was caused by the situation, the fact that her parents had no idea where she was, that she hadn’t had anything to eat since dinner the night before, and that a man with a kind voice and a long ribbon of hair, a man who was of people who had things worth remembering, was becoming her friend. Just then, his hair was brushing her arm, his full purple lips were parting slightly to ask, “How old are you Patsy Smith?”

“I’m old enough to know what you want. And I’ll tell you something, Handsome Lake, I want it too.” It came out just like that, one whole piece, smooth as something memorized. But she had never before said anything like it. She watched his face, gauging the effect, and then, with the same quiet authority the first violinist in the orchestra lifted the bow and laid it across the strings in preparation to begin the symphony, she raised her arm and set her long, pale-fingered hand on his blue jeaned thigh. Every Saturday of her entire life, her mother had gone to the Rochester Philharmonic. And so it was on that beautiful afternoon she was sitting in the audience, straight-backed and focused, as her daughter, who cared nothing for classical music, was sprawled on the ground a hundred and forty three miles south, orchestrating, with the same drama and promise, slender fingers on a stranger’s thigh.

But the Keeper of the Western Door leaned away. He sat back against the tree trunk and said, “There’s nothing special here. Nothing romantic. What we have is poor land and complicated weather. This is the place, Patsy Smith, where all hopes are destroyed, all expectations are lowered, and every vision of the future is worsened. I’m warning you. Anyone who survives crawls away injured. So do you really know what you’re doing? Because the only thing to recommend me is the before and the here, the this.” He put a lean hand on the ground underneath him. “But not the after. Clear on that?”

She loved the sound of his voice. She could just lie down and listen to that kind of poetry all her born days. Uly Jojockety was a teacher. He would teach her everything she needed to know. She removed her hand from his thigh, unzipped her jeans, and pulled them down, flinging them off with a heroic flourish. Oh, the terrible wrongs that had been done to him and his people!

But then, as his body moved over hers, cutting out the light, there was a moment that dropped out of the progression. She knew she would remember it. It was before anything happened, when she was still a girl from a suburb of Rochester escaping difficulties at home. And then, as those rough hands discovered her, she watched herself become someone else, someone she hadn’t met before, someone who was outspoken, a woman who would be comfortable in her life, who would feel for others. She’d say, sweetheart, honey, baby cakes, announcing her affection for whomever it was she spoke with. That person would take over. She would lead her from one sorry man on the earth to another, moving from Salamanca, New York to Olean, Batavia, Buffalo, always keeping to the clouded western side of the state until she’d had enough of other people’s troubles. The wisdom was hard-earned. And when she was in her fifties, having been through it all — children, booze, narcotics — her body would cease its raging.

But that was the future. It would take thirty-seven years to get there.

Listen to Megan Staffel’s reading of “Saturdays at the Philharmonic” below…

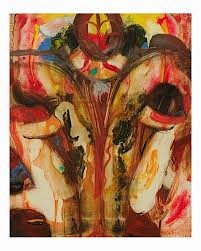

Megan Staffel explains that this untitled painting by Annabeth Marks feels connected to her story because it “expresses female sexual longing.”