INTERVIEW WITH Ayesha Raees

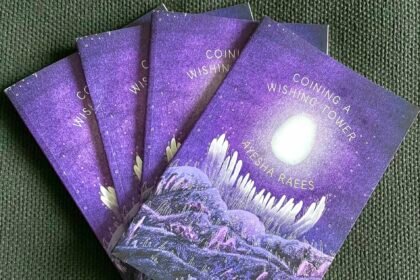

Ayesha Raees’ fabulist and fable-like chapbook, Coining a Wishing Tower (Platypus Press Broken River Prize winner, 2020, selected by Kaveh Akbar), is composed of 56 prose-like blocks—give or a take a few half-fragments.

These prose-poems, which are whimsical, profound, vulnerable, and full of pathos, grief, and transformation, depict complex relationships between parents and child, religion and women, lovers and the beloved, wishers and wish-granters. There are three separate narrative strands, teleporting between Pakistan; New York City; Makkah; New London, Connecticut; as well as more abstract spaces, like a Desire Path, as well as Barzakh (which, the chapbook tells us, Google calls a “Christian Limbo”).

The first narrative involves House Mouse, who climbs and climbs until the “end of all possible height” and finds itself in a wishing tower which can grant all its wishes. House Mouse performs various rituals including the ritual of death—in which both House Mouse and the tower die. The second strand, taking place in a wooden house in New Connecticut, involves three characters: Godfish, a cat who is in love with Godfish, and the moon, who is also in love with Godfish. And finally, there is the more realist narrative strand, with a female speaker—a daughter and an immigrant—who seems to speak for Raees herself, and her own personal experiences with family, religion, migration and displacement.

She is interviewed here by Cleo Qian, previously published in Issue 25.

CQ: How did you come up with the characters of House Mouse, the tower, Godfish, the cat, and the moon?

AR: Each character in the book embodies, not always wholly or too literally, a person of importance from my life. The book itself was conceived the night that I found out my best friend, Q, was in an irreversible coma due to a (eventually successful) suicide attempt. The characters in the book are my own reckoning with the different facets of the deaths we face in our lives before our eventual, more literal, ends. But I did not want this book to be so linear or literal; I wanted it to tackle death in varying ways.

House Mouse represents every young immigrant. Immigrants must leave their “selves” or “homes” for a better future, which is the mirage of the “American dream”—which calls for outsiders to come in and fill the gaps of a decaying system. Asian immigrants also, in many ways, are pressed for success or “height” to obtain ‘value’ from a very young age.

As a poet, “House Mouse” is also a play on words. What happens to a common house mouse when it is without a house? What happens to a young immigrant when they leave their homes for the world’s seductions?

The wishing tower is a symbol of the Ka’abah but is also something of extreme physical height, an unreachable thing. “Coining” in the collection’s title reflects stoning—a visual gesture, with prayers or wishes. Godfish is a play on goldfish, but this character also represents another close friend of mine, A, who was another young immigrant who left home to America to pursue another life and was lost in a tragic way. And the cat and the moon are, at the end of the day, spectators, both holding power but choosing to practice it in different ways; they are two faces of a white savior complex and American passivity.

I don’t believe I would have been able to say all I wanted to say without the aid of characters in this book.

CQ: Let’s talk a little bit about the settings mentioned throughout the book. What is the significance of the setting New London, Connecticut? Early in the book, you write, “I have never been to New London, Connecticut.” In the narrative of the Godfish, cat, and moon, New London is both real and unreal, and the wooden house they live in is centric to “unnatural happenings” and set apart from the “real life giant black road.” And what about the sites of pilgrimage throughout the book? Is America also a site to make a pilgrimage to, or is it a place to escape to?

AR: I have a love for places and the social cultures they inevitably hold. I am someone who has been in constant movement her whole life, and I believe places to be their own characters, to have their spirits. Therefore, the different locations in the book are all real, even the unreal ones. They are their own breathing, living organisms.

And that’s how New London, in Connecticut, feels to me. I have never been. In the book, it is a place of “unnatural happenings” as, just as written in the book, it is a place where Godfish died.

The character who is embodied in Godfish was my high school best friend, A. He went to Connecticut College (in New London, Connecticut) and was hit by a drunk driver while he was crossing the road at night to go to his dorm. The drunk driver, instead of calling for help, pulled A’s body aside and drove away. Leaving him. Right there. To spend a cold December night outside. He was found the next day. His date of death is merely an estimation.

I was myself a sophomore at Bennington College when I received the news. This was December 2015. I was devastated. Over the years of grieving, New London, Connecticut became a significant image for me. The side of the road A was on was very real. I don’t know what it looks like in real life. But in my head, there is a whole image. I live with the happenings of that night every time I am grieving. How can I have such vivid imagery exist when I was not even physically present? That’s the power words have over me.

The moon that captures and cannot fully lift Godfish embodies “moonshine,” intoxication, which failed both Godfish (and A). In the end, my friend was a gold marking on the road. And I believe when I started to write about Q [my friend who passed away after being in a coma], A came forward into the poetry as well. They both took me on the journey of characters and settings, and the book’s narrative reckons with all our losses and its impact.

Is that a sort of pilgrimage? I believe so.

CQ: The book opens with House Mouse climbing and climbing until it gets to the wishing tower. Godfish wishes to be able to swim to the sun, its beloved. The moon wishes to draw Godfish to itself. In Islam, Jannat-ul-Firdous, we learn, is a “place in heaven that is of the highest level, reserved for the most pious, the most special, the most loved.” Do you think the striving for height is a universal human desire? How do height and religion intertwine?

AR: Who are we but an accumulation of our wantings? Humans have inane, uncontrollable, desires that make us get out of the ordinary and strive for something that can give us, even for a single moment, a rich breath of fresh extraordinary. To be human is to be full of wanting, to exist in that kind of inevitable strive. And that kind of striving will always achieve some kind of height.

But my goal through the book, and of course for my own reckoning as a young ambitious Asian immigrant in the American landscape, was to ask what those systems of value ask of us. These “heights” we climb to that are a measure of our worth, giving our human life a value. In order to have value, we keep climbing. But until when?

I was thrown into this disarray because Q and I were ambitious young Asian women from so-called “third world countries” and quite alike in our dispositions. We wanted to be accomplished. To have value as individuals and not be reduced to our Asian womanhoods. But that striving killed us. I watched her fall. And I found myself falling. Like most Asians, we were sold to ideas of hard work leading to value, such as our grades, the length of our CVs, the honors and fellowships and residencies and awards. We were accomplished. But we did not have enough value to win the system that was built against us.

So what did we strive for?

As I was grieving, religion became my literature and God my mentor. I grew up with Islam but as with most religious countries, religion seeped in as a way of life rather than a radicality. Islam is a part of my cultural identity. It is part of my language. Islam is a constant reminder of how to live a life that prepares us for death. And even though I am (and was!) so young, to be handed so many deaths of so many loved ones left me in disarray. I was alone in the American landscape without much support or, as we all have experienced our capitalist systems, empathy. When I finally turned again towards Islam, I was looking for some sense that the West, and Western literature, could not afford me.

I will always say that I am not a religious person. After all, religion is a tool to control the masses. I don’t want Coining A Wishing Tower to be a religious book. I am, however, deeply spiritual. I do have faith in the unknown. I do believe in a God. Maybe when I am brave enough to proclaim it externally, I can even say my God. I have belief in the many rituals that help us decipher the literals of our lives towards a healthy figurative. A true kind of poem. It is inevitable for me to not see God with poetry.

CQ: Many of the prose poems—and the arcs of the House Mouse, the tower, the Godfish, cat, and moon—are written in a parable-like tone. Some of them also verge on fairy tales. You have such wonderful lines and imagination when, for example, House Mouse is cooking in the tower:

“House Mouse cooked fish for the first meal, corn for the

second meal, and melted cheese for the third meal. The

tower is one room full of great imaginings working towards

not staying imagined…”

Or when the moon tries to bring Godfish to itself:

“With every mustered strength, the moon lifts the water, rounds

Godfish into a dripping ball and pulls it through the opened

window only to bring it to a float and a hover in the storming

snow of New London, Connecticut….”

What was the influence of parable and fairy tale in your writing of these poems? Do you consider these narratives allegories?

AR: I celebrate poetry because a good functioning poem has great intentionality. If you spend enough time even with a single line, you can see how the poet has chosen to lay the words next to each other the way they are. Nothing is random. And everything adds to something else.

I do a lot of work with symbolism and imagery, often lent from my own life. I am always in awe at the contrast and the magic I see in front of me. For example, I am currently in Paris, sitting in a gorgeous reading room at Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Public Library of France) answering these questions, where I find myself watching a parade of silent children running through the rows of hunched working adults. They are not laughing. Or making any kind of noise. They are just running through the gorgeous rows of tables. What a contrast! What image and magic! And hardly anyone is looking up! Doesn’t that feel like a fairy tale? Or an allegory? Children running through a grand beautiful reading room of a world-famous library full of frowning adults?

I do the same in the verses you have pointed out. When I put [these contrasts] of the imagined and unimagined together, I surprise myself.

CW: Do you believe in epiphany? How does epiphany play a role in these poems?

AR: I believe in wonder, which can be quite like epiphany, but is not always the same. Epiphany feels like a lightbulb moment of occasional discovery, but wonder feels like a series of discoveries that were always present but are now fully being seen.

In this way, the form of the book holds a kind of wonder. It is an epic told in fragments. Even though I wrote it linearly and the editorial process did not include rearrangements but just clarifications, I saw how one narrative thread began to breathe while still supporting the other threads.

When I read the book out loud in readings, I flip through the book at random and read pieces from it. I am faced with more wonder in this as well.

CQ: Google is also frequently cited throughout the poems. Often, Google’s word is taken as factual and fills in missing gaps in the speaker’s knowledge—e.g. Google speaks on the status of New London, Connecticut, as a small city; on how many lives cats have; on what Islamic Barzakh is. Why did you invoke Google and what is the role of human technology in understanding these characters and poems?

AR: Isn’t Google some form of god now? We rely on it for all our small and big questions and immediately believe what it tells us. “Google says…” instead of “God says.” I find in both these common phrases a kind of significant mimicry.

In a past that’s not too far off (I am thinking of my parents’ lives), information was not accessible at all. My parents were probably faced with so much unknown but still had to strive forward with whatever understanding and skills they did have. They couldn’t just Google how to exactly use a new microwave they bought or how to apply for a visa to travel. In these observations, Google has become such a huge part of our contemporary lives that without it, we wouldn’t often know what to do. And with it, we often are also told how to live a life and exactly what to do.

Maybe I wanted to have Google in the book because so much of our consolations and salvation hinges on asking. In the past, we sat in prayer and asked. And now we get on our phones, maybe our hands poised ritually the same, and ask. We get answered in both ways. We believe. And sometimes, we don’t.

CQ: Another theme that pops up in the latter half of the book is forgetting. Of the Islamic heaven, you write, “Any kind of remembrance of our past lives, any regret, every love, it will all be flushed.” You, the speaker, ask if you will be forgotten on the day of judgment, and the mother says, “It’s inevitable…you will forget me too.” When the cat finds Godfish, dead, you write, “Would death tear them apart to a degree of absolute forget?” These lines really tugged at my heart. The fear of forgetting my loved ones after death is terrifying . How are these poems a response to the question of whether death is the ultimate forgetting?

AR: What we don’t remember also brings us relief. That’s the concept most Muslims have about death and afterlife. If I don’t remember the extent of love I feel for my mother, I would not feel the extent of her loss. I would be relieved of grief and the pain of it.

This is scary. But also, to some degree, comforting. There is consolation in thinking we won’t always be yearning for the ones we lose.

I have tried to tackle the question of love and endings through the poems in small and big ways. The last prose block of House Mouse “returning” holds that life and death can exist in mimicry. But what bridges each ending with another beginning is change and transformation.

CQ: There are a series of transformations: Godfish into a fish, the wishing tower into a pile of rubble. Are these “failed” transformations? Are they an inevitable part of the cycle of life?

AR: I don’t believe in “failed” transformations, and I think maybe that was what I was trying to truly say throughout this epic. Even though Godfish loses its God-ness, its existence still transformed the moon and the cat. The wishing tower is no longer able to grant wishes, and then it loses its life. But it transforms into something else, even if that is rubble which will erode away.

These losses are, in some ways, an indication of life’s inevitable end, yes, but [writing this book] also gave me the gift [of knowing] that there will always be some kind of other journey. Any end we think of is a ripple effect towards something else, beyond comprehension.

These fragmented thoughts are captured in the fragmented poems. We can see the “afterlives” of House Mouse, the Godfish and the tower. [I wanted to show how] there is never any true failure in our conventional ideas of failing. Things that “fall” fall to somewhere else.

CQ: Do you consider these poems of loss?

AR: Absolutely. But not only. These poems are full of grief. But also consolation. Also philosophical nurturings. They are an encouragement to move away from our unconventional thinking of the most universal experience of loss itself.

CQ: At the end of the book, House Mouse is somehow resurrected. I loved this ending, which felt joyous, miraculous, and yet also sad and full of grief because there is no one around to meet House Mouse. What are we to make of House Mouse’s return to life? What is House Mouse returning to?

AR: House Mouse holds huge parts of me as well as huge parts of the speaker, which, of course as poets say lingo, is both me and not me. The speaker leaves home, Pakistan, and goes to America, fulfilling her teenage dream to leave, but the speaker also returns. And with every return, there is change. Decay. Death. Loss. Transformations.

And each immigrant really asks these questions if they return [to where they have left]: “What am I returning to?” “What makes life life here and how much of it I have left?” “Who waits for me and who could not?”

“What has died and what still lives?”

Returning is hard. It is full of lamenting and an inconsolable feeling. We have to reckon with the relativity of time, the loss of romance, and changes that override our initial memories. House Mouse finally returns to the home which it left in the first prose block of the book. But so much has changed. What is home now?

I think there is consolation and love in the fact that we have our return. Even if our parents die. Even if our houses change. Even if the furniture gets full of dust. Just because there is this kind of loss, does not mean we do not feel all the presence of what home is there. Maybe, in life, forgetting can relieve us of pain, but remembrance reminds us of the original love we were given, however much it has been transformed.

CQ: You published Coining a Wishing Tower during the lockdown. Where were you, location-wise, when you heard that your book was accepted for publication? How did COVID-19 affect your experience writing and publishing this chapbook?

AR: This is actually a funny story. The day I got the email that I won the Broken River Prize from Platypus for the book was also the day Biden won (or, well, Trump lost) the elections—November 7 2020. We were all under strict Covid lockdown, but because of the election results, the streets of Brooklyn were flooded with cheers and shouts and music. We all ran through the streets. In that way, I felt I was also celebrating my own little win of accomplishing a dream (the wish I had coined a long time ago). The book was mostly written in 2019 around the loss of Q. But this book definitely was a huge victim of the pandemic aftermath. What with delays in publishing and then my press’s bankruptcy, my book only had a life in this world for one year. But I believe in its return. The life after its life.

CQ: What’s next for you?

AR: Even though I often fail to keep it as simple as the words I am about to say, all I truly desire is to keep writing. I am deeply in love with poetry. And I don’t think this affair will end at all. I am hoping to keep at it and, in small and big ways, keep being read.

To more poems! To more books!

Ayesha Raees عائشہ رئیس identifies herself as a hybrid creating hybrid poetry through hybrid forms. Her work strongly revolves around issues of race and identity, G/god and displacement, and mental illness while possessing a strong agency for accessibility, community, and change. Raees currently serves as an Assistant Poetry Editor at AAWW’s The Margins and has received fellowships from Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Brooklyn Poets, and Kundiman. Her debut chapbook “Coining A Wishing Tower” won the Broken River Prize, judged by Kaveh Akbar, and is published by Platypus Press. From Lahore, Pakistan, she currently shifts around Lahore, New York City, and Miami.