FIRST WINTER by Hala Alyan

Our bodies are urns full of rain,

spilling during the harvest. The elders

speak of clemency. The army marches on.

We watch them across the ocean,

speak their undead name in our sleep.

Some of the sisters still make mosques

in abandoned lots. They auction their gold

for Allah’s ninety-nine names, while

the neighborhood boys hawk the spires

for cocaine. In the hour of the blizzard,

the devout speak of owls rising from

fossil. When they bathe, they hear

children’s voices in the pipes, open their

mouths wide to catch that scalding

song. Their wombs are empty now.

They name the trees in the projects for

Hagar. Snow fills the minaret and they wait

to arrive, finally, shaking, to god.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Two Poems by Patrick Rosal

TWO POEMS by Lee Sharkey

CIVILIZATION

Even in the most inhospitable circumstances there is always time for a cup of tea.

Say you live in a cup with a hole blasted in its side in a blasted landscape, by a blasted tree

and an empty barrel. You can still park your worn down shoes side by side

at the door and steep your questions in hot water. Since you are a man of letters

I imagine you have many. As steam brushes your cheeks you may read the leaves.

Take your time. The wind is aroused and the clouds are either massing or clearing.

You have lost everything but not what makes you human. I don’t mean your coat and tie.

SHELTER

The forebears have gathered. The clocks have split open. Clock hands lie on the ground

like bent utensils. The forebears emerged through the rock. They are ruins. Dissevered.

Parallel faces frozen in profile. The forebears are listening. And there you stand

(I almost missed you), memory’s king, an ant among giants, hands tucked in your

pockets, downcast, with a stone for a shadow, waiting for whispers, husbanding

wisdom, at home at last in an old stone Eden. Whose face does the rock face bear

and repeat, each and every — your face, God face, Jew face, membranous blessing.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: Trees by David Lawrence

STACK OF BRIGHTNESS by Rosalynde Vas Dias

What do you know

of the former

beloved/still beloved?

He lives in another

city or speaks

infrequently.

He appears

in the guise

of an owl, he appears

in the guise of a scrawl.

In a series of paintings—

peasant villages,

festive skies—

your two selves

are fractured

and played by

a bunch of characters.

You are close and you

are friends and you recede

endlessly from one

another.

It means you,

singular, string beads.

You make a lot

of bracelets. They grow

up your arm,

a stack

of brightness,

static of the

rainbow. You

(plural) used to make

omelets together

or something.

Issue 6 Contents NEXT: The Smallest Man by Julie Brooks Barbour

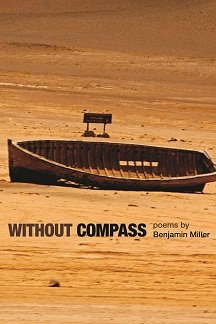

Three Poems by Benjamin Miller

IN THE PLACE OF BEST INTENTIONS

As this is not the land of ice packs

and regenerations, of spent glue guns

or antiseptic counters—since shy

reminders filter through the streets all night

(mountain streams that city fountains sip)

absconding with old disappointments—

because the powerlines are wet with flames

that spill their music into shallow halls

devoid of short-term motives, I am lost

and cannot say what may have led me here

to watch the girls unwrapping fiberboard

from miles of burlap while the waitresses

tattoo their angry daisies on my arms.

What is this place that leaves me so unmoved?

A hat I’d never worn or wanted worn

is now my prized possession; tissues packed

into abandoned zipper pockets breed—

I had forgotten that the small glass cups

were hidden in my socks and that my hands

were laced with fine red scratches

long before the advent of arrival. Now I feel

the heat of my illusion dim to tremble,

a dull intrusion into some romantic

basement of unknowable books. And so

forgive me if the water left for tea

is steeped in silt and valentines; forgive

the unexpected token undisclosed.

Last night I thought I wanted tragedy,

a chance to wick away the morning’s

donut, bagel, muffin, scorn. But to span

the gap from night to night, from night

to some hello, is more than I can yet

achieve: a phone that rings without response

and without end or empathy.

Belief is a raft tossed out on a thirsty plain.

Were I that lonesome, I’d never have left.

ON THE MARGINS OF THE PORTABLE COUNTRY

The making of ideology, of how stories learn,

ends in bone. Thus, facts without lives are trouble.

Even squall, the art of, must learn to scramble hours

as the scribblers do; and so some argument electric

in its innocence arrives to silver fictions

out of mauve and maudlin discipline.

All worthy hearts embark. But who returns

from such a journey—who could tent beneath

that zoo and cairn with time’s fool law

and still press on unscathed? (The lathe, the nick,

the cutting tree remembering the cutting.)

On the margins of the portable country,

a stranger compendium lands its craft

of pleasure and scorn, a balloon

in love with a wood, a turtle fallen

from the subjunctive into the academy.

I’ve started marking up a manual of dangers.

You have not all been selected.

IN THE WAKE OF AVOIDABLE TRAGEDY

What little remains is clear: it is over.

The first and the last having gone

and returned, come and returned,

we have learned to welcome those

who make the place feel welcoming.

A guitar in the corner hoards the light,

says: you, in a collapsing world,

your eyes such sharp, undarkened things.

From Without Compass (c) 2014 by Benjamin Miller.

Reprinted with permission of Four Way Books. All rights reserved.

“In the Wake of Avoidable Tragedy” was first published in The Greensboro Review.

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Poetry, Series

Three Poems by Brian Komei Dempster

CROSSING

No turning back. Deep in the Utah desert now, having left one home

to return to the temple of my grandfather. I press the pedal

hard. Long behind me, civilization’s last sign—a bent post

and a wooden board: No food or gas for 200 miles. The tank

needling below half-full, I smoke Camels to soothe

my worry. Is this where it happened? What’s left out there of Topaz

in the simmering heat? On quartzed asphalt I rush

past salt beds, squint at the horizon for the desert’s edge: a lone

tower, a flattened barrack, some sign of Topaz—the camp

where my mother, her family, were imprisoned. As I speed

by shrub cactus, the thought of it feels too near,

too close. The engine steams. The radiator

hisses. Gusts gather, wind pushes my Civic side

to side, and I grip the steering wheel, strain to see

through a windshield smeared with yellow jacket wings, blood

of mosquitoes. If I can find it, how much can

I really know? Were sandstorms soft as dreams or stinging

like nettles? Who held my mother when the wind whipped

beige handfuls at her baby cheeks? Was the sand tinged

with beige or orange from oxidized mesas? I don’t remember

my mother’s answer to everything. High on coffee

and nicotine, I half-dream in waves of heat: summon ghosts

from the canyon beyond thin lines of barbed wire. Our name

Ishida. Ishi means stone, da the field. We were gemstones

strewn in the wasteland. Only three days

and one thousand miles to go before I reach

San Francisco, the church where my mother was born

and torn away. Maybe Topaz in the desert was long

gone, but it lingered in letters, photos, fragments

of stories. My mother’s room now mine, the bed pulled blank

with ironed sheets, a desk set with pen and paper. Here

I would come to understand.

TEMPLE BELL LESSON

Son, I am weighted.

You are light.

Our ancestors imprisoned,

outcast

in sand, swinging

between scorching air

and the insult

of blizzards.

Their skin bronzed

and chilled

like brass,

listen

to their sorrow

ringing.

GATEKEEPER

Any noise alerts me. My wife Grace shifts beneath our comforter.

Respecting my uncles long dead, I climb from bed, grab

the bat, climb stairs, walk halls with a thousand sutras shelved

high, my grandparents’ moonlit ink floating on pages sheer

as veils, the word Love rescued from censors. In the nursery

I check window-locks, sense my son Brendan falling in and out

of seizures and sleep. Backed by the altar, its purple chrysanthemum

curtains, gold-leafed lily pads, corroded rice paper, I crouch

then stand at the window to watch silhouettes fleeing

past streetlamps, the gate unmoored from its deadbolt, unhinged

from ill-fitted screws and rusted nails. The front door cottoned

with fog shakes in night wind. Backyard bushes rustle. For now

I let the mendicants crack open our prickly crowns of aloe, soothe

their faces with gel, drop bottle-shards and cigarette butts that slash

and burn our stairs. Inside, we fit apart and together.

Grace and Brendan sleeping, me standing guard.

From my grandfather’s scrolls moths fly out, and I grab at air

to repel the strangeness of other lives circling toward us.

From Topaz (c) 2013 by Brian Komei Dempster.

Reprinted with permission of Four Way Books. All rights reserved.

An earlier version of “Gatekeeper” was first published in Parthenon West Review.

|

Topaz, Brian Komei Dempster’s debut poetry collection, examines the experiences of a Japanese American family separated and incarcerated in American World War II prison camps. This volume delves into the lasting intergenerational impact of imprisonment and breaks a cultural legacy of silence. Through the fractured lenses of past and present, personal and collective, the speaker seeks to piece together the facets of his own identity and to shed light on a buried history. |

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Poetry, Series

Three Poems by Sam Sax

I.35

i watch him touch him self over a screen

and pretend it is with my hands

how you pull a quiver from an arrow.

he moans and i grow jealous of the satellites.

their capacity for translation, to code his sound

in numbers unbraiding in my speakers

lucky metal audience of cables.

i know the wireless signal is all around me,

that i’m drowning in his unrendered noise.

how from a thousand miles away i can dam

myself with the light spilling from his hands.

what magic is this? distance collapsed

into the length of a human breath. what witchcraft?

six years ago a bridge between us collapsed

the interstate ate thirteen people alive

asphalt spilling like amputated hands

into the dark below. what is love but a river

that exists to eat all your excess concrete

appendages? what is a voice but how it lands

wet in the body? what is distance

but a place that can be reshaped through language?

how i emulate and pull a keyboard from the ashes.

how i gave him a river and he became it’s king.

how any thing collapsed can be rebuilt.

take our two heaving torsos take them

how they fall like a bridge into the water

how they rise up alone from the sweat.

BILDUNGSROMAN (SAY: PYOO-BUR-TEE).

i never wanted to grow up to be anything horrible

as a man. my biggest fear was the hair they said

would burst from my chest, swamp trees

breathing as i ran. i prayed for a different kind

of puberty: skin transforming into floor boards,

muscle into cobwebs, growing pains sounding

like an attic groaning under the weight of old

photo albums. as a kid i knew that there was

a car burning above water before this life,

that i woke here to find fire scorched my

hair clean off until i shined like glass – my eyes,

two acetylene headlamps. in my family we have

a story for this. my brother holding me

in his hairless arms. says, dad it will be a monster

we should bury it.

MONSTER COUNTRY

god bless all policemen & their splintering night sticks splintering & lord

have mercy on their souls. god bless judges in their empty robes who send

young men off to prisons with a stain from their antiquated pens. god bless

all the king’s monsters & all the kings men. god bless the sentence

& its inevitable conclusion. god bless the predators, curators of small

sufferings. god bless the carpet that ate one hundred dollars of chris’s

cocaine. god bless cocaine & the colophon of severed hands it takes

to get to your nostrils. god bless petroleum & coffee beans & sugar cane

& rare earth minerals used to manufacture music boxes. god bless the gas

chamber & the gas that makes the shower head sing. god bless the closet

i trapped a terrified girl in with my two good hands. god bless the night

those good boys held my face to a brick wall & god bless those boys

& good god bless the strange heat that pressed back.

you cannot beg

for forgiveness

with a mouth

A Guide to Undressing Your MonstersComing soon from “Sam Sax’s poems are ravenous, intimate, and brutal. God is ‘a man with a dozen bleeding mouths’ and ‘a boy drags his dead dog across the night sky’ and ‘shadows sing.’ Tongued and loved, a butthole becomes a trumpet, a second mouth. His poems reject the given. His poems seek out new encounters between flesh and world, between language and memory. Bristling with stunning images and formally astute, his poems nurture and bruise.” ~ Eduardo Corral |

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Poetry, Series

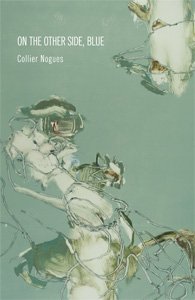

Three Poems by Collier Nogues

MISSISSIPPI

I know forgetting myself is a good thing, the best loss.

The trees look soft in the fog’s distance, egg-colored light

all over them. Even the sheep,

eggy.

The earth dries in ribs the rain has drawn on it.

Trees here grow up out of the water. Too little light

to tell what color but the ground that isn’t shining is made of leaves.

So these pools are mirrors:

were it on earth as it is in heaven,

blue land of we-will-all-meet-at-the-table,

I could be for other than myself successfully

without first having to lose someone I love.

THE FIRST YEAR IN THE WILDERNESS

i. Spring

My friend’s little daughter was pulled

under.

What began as a single

instance of labor became

circular:

the child’s mother on her hands

and knees, pushing

floor wax into tile grout

across the emptied house.

ii. Summer

Every window

hung with stained glass crosses

casting rainbows,

coloring

the throw rug and the wall.

Men. Silence,

great crashes of noise at long intervals.

The cat sacked out on the floor.

iii. Fall

Her prayer:

My preparations have outlasted

your stay,

so I have not only

the afterglow of you but also

little signs still

that you are bound for me.

iv. Winter

The only place open after midnight:

tall-stalked bar stools,

the valley laid into the wood

of the wall.

We stayed up

with the lottery sign’s crossed fingers,

while the animals

lay down in the field.

EX NIHILO

The beginning is spring.

The lanes are lined with poplars who lose their leaves to winter

but to whom nothing further wintry happens.

I design it so the marriage lasts as long as the lives,

and the children outlive their parents.

They are all startlingly easy to make happy. They recover

from unease like lightning.

When it falls apart my frustration is like a child’s,

unable to say, unable to make something

happen by saying.

To speak in someone else’s voice is a pleasure, but not a relief.

My tongue burns in its cavity.

My recreation of us is unforgivable

in the sense that I am the only one here to forgive it.

|

“Collier Nogues is a rare poet in the contemporary landscape. Her work is rife with the quick jump-cuts and fragments many young poets favor, but there’s no cynical irony for irony’s sake in her poems. This is poetry that earnestly engages with life’s big questions….A poet is, among other things, a protector of thoughts, a kind of police officer of the inner world. Nogues… makes it a little safer to think, a little less frightening and lonely.” — Craig Morgan Teicher from “Introducing Collier Nogues” in Pleiades, Volume 30 Number 1, 2010 |

- Published in Featured Poetry, home, Poetry, Series

ELEGY WITH SHOTGUN by Anna Claire Hodge

Once you warmed the shower wall with water

before pressing me against it. Some nights,

the bed was feverish heat. You, a man

burning, as the sheets twisted into peaks

not from our lovemaking, but nightmares.

So similar to the snakes in mine: centipedes,

the threat of their endless segmenting. Breaking

apart like mornings you left me for food or family,

the wife and daughters towns away who will never

know my name, theirs on your lips in a way

that gave me pause, that their conjured bodies

might leave the room first, let me have you fully,

before I leaned to kiss you. Tomorrow, I will drive

to the ocean, past the fish camps and souvenir

shacks, to the town where soon my sister will be wed.

She will tell me that she, too, once loved a man

whose brain burst into lace as he vowed himself

to trigger, hammer. She will turn as I enter the room,

careful not to shake loose our mother’s veil

bleeding from her blonde hair, same as mine.

And if I must look away, it will be to the grey

of our wintry piece of ocean, as I imagine a swim

so far from land I might find you whole

and floating, no barrel poised in your gorgeous mouth.

Issue 5 Contents NEXT: Wrong About That by Paul Beilstein

WRONG ABOUT THAT by Paul Beilstein

I thought my sadness was a moron’s elbow.

Thought I could offer it a salve,

or the comfort of a well-worn arm-chair.

I thought I could buy a corduroy shirt

and wash it the exact right number of times.

I hope you have better ideas about yours.

Maybe yours is the referee

of the driveway free-throw drill

I practiced evenings after dad’s no-chop dinners.

Back then, he had a rule for keeping things simple,

but lately I’ve seen him take knife to carrot,

tomato. Maybe yours is the referee,

who helped me count how many

out of one hundred I had made.

It is hard to make friends with the pinstriped,

but I have seen signs on television.

Maybe your sadness is the small belly

peeking through the misty t-shirt

of the early morning jogger, increasingly

invisible to all but the most unkind.

Maybe you are the master of sadness and yours

is the beagle’s drooped ears,

or the quadriceps of the bicycle commuter,

or the tear in the beagle’s owner’s tights,

which must be too comfortable to discard

for such a slight disfigurement.

After each miss, the referee stood under the hoop

unwilling to chase the ball, but after a make,

he gathered it, spun it in his hands as if

examining it for disqualifying flaws,

then snapped a chest pass back to me

with the form my youth team’s coach

must have dreamt of while his wife sat up

watching him whimper and squirm.

I caught the ball, with a developing sense

that something was horribly wrong.

I focused, made eight in a row.

I wanted to know more.

Issue 5 Contents NEXT: Two Poems by Jane Wong

TWO POEMS by Jane Wong

DIVING

To become a world carry your wounds with you:

bright plums split on a dish

a scattered alchemy in the limbs metal upon heart upon glint

could you ever leave? Steal this

in passing, in looking sideways: an owl, a doorway

ever-crooked I have no use for perfect vision

walking downhill always means hold on

to me like a rush of insects ringing heavy in the bells

in a key of light dive bombing outside my window, alight –

my advocate of world-making I assume that you can hear me

tapping along the wall testing poetry or

the solidity of my name language has nothing to do with what I want

these heaps of words, stone upon stone cairn to mark the way above a tree

line, pointing think of the wound instead –

the units of the wound, these lake-worthy moments

the boarded – up houses we sleep in

BREAKER-OF-TREES

My mother cuts the legs

off a moving crab.

The legs curl in a bucket

washed to garbage

to sea. When I come home,

I tread water on the carpet

and hang my head low.

Guillotine of the heart,

the wind causes trouble

between two trees.

The trouble causes splinters

enough to build a forest

in just one hand.

What can we learn

from disaster if not

the familiar angles of a face?

How I can touch yours and say Paul.

I crack open a geode

as a reminder of grace.

From the crystal center,

yolk splinters, pours.

Issue 5 Contents NEXT: Two Poems by Gregory Pardlo

TWO POEMS by Gregory Pardlo

25. Ellison, Tony Samuel, et al. Photograph Album. Twenty-two Albumen Prints: Life in the Louis Armstrong Houses with Views of Marcy Ave. Brooklyn, circa 1986.

A quaint example of urban pastoralism typical of an age when public policy and planning isolated urban poor like so many shepherds on a hill, these images capture a distant and harmless charm. A city block is cordoned for a riverless baptismal, for example; the skin of churchwomen in white linen buffs brown and brightens in sunlight beneath the spectrum shimmering from a fire hose, a curious counterpoint to hoses of Birmingham, these aimed skyward as if to cleanse the undercarriage of every chariot in heaven. In a style that marries Edward S. Curtis and Walker Evans, these images witness conflicting efforts to ennoble a stigmatized community. Of note is how the boom boxes of the youths, their fat shoelaces and hair-styling rituals obscure more complex, personal rites that would otherwise lift them one by one from the muck of type. Yet there is joy; the face of the bodega’s happiest man alive is carved from laughter and a lifetime of tobacco use. Carved deep like the rivers. Sentimental and simplifying, these images highlight the ease by which other can conceal a verb.

Oblong quarto, period-style full green morocco gilt; 22 vintage albumen prints, each measuring 8 by 10 inches; mounted on heavy card stock each measures 10 by 14 inches. $7500.

Original photograph album of Urban America circa 1986, with 22 splendid exhibition-size albumen prints

__________

837. Wilson, Shurli-Anne Mfumi. Black Pampers: Raising Consciousness in the Post-Nationalist Home. Blacktalk Press, Lawnside, NJ, 1974. 642 pp., illustrator unknown. 10 ½ x 11 7/8”.

Want tips for nursery décor? Masks and hieroglyphics, akwaba dolls. Send Raggedy Ann to the trash heap. This tome is a how-to for upwardly mobile black parents beset with the guilt of assimilation. Revealed here are the safetypinnings of the nascent black middleclass, their leafy split-level cribs and infants with Sherman Hemsley hairlines. Of interest are bedtime polemics on the racist derivations of “The Wheels on the Bus.” Chapter headings address important questions of the day: How and how soon should you intervene if you suspect your child lacks rhythm? When do you prepare your little one for the historical memory of slavery? And the two cake solution: one party for classmates, and another one you can invite your sister’s kids to. Indispensible to collectors for whom Aesop’s African origin is no matter of debate, a more appropriate title for this book might nonetheless be, “What to Expect When You’re No Longer Expecting Revolution.”

Usual occasional scattered light foxing to interiors; contemporary tree calf

exceptional. About-fine condition. $75.00

Issue 5 Contents NEXT: The Rabbit by Sarah Huener